| The term "hieroglyphs" in hieroglyphics

|

Sesch-ni-medu-netjer

Sš-nj-mdw.w-nṯr

" Scripture of God's Words "

|

The Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ancient Greek ἱερός hierós , German 'holy' , γλυφή glyphḗ , German 'scratched' ) are the characters of the oldest known Egyptian writing system, which dates from around 3200 BC. BC to AD 394 in ancient Egypt and Nubia for the early , ancient , middle and new Egyptian language as well as for the so-called Ptolemaic Egyptian . The Egyptian hieroglyphs originally had the character of a pure picture writing . In the further course, consonants and symbols were added, so that the hieroglyphic writing is composed of phonograms ( phonograms ), symbols ( ideograms ) and Deutzeichen ( determinatives ).

With originally about 700 and in the Greco-Roman period about 7000 characters, the Egyptian hieroglyphs belong to the more extensive writing systems. A sequence similar to an alphabet did not originally exist. It was only in the late period that single consonant characters were probably arranged in an alphabetical order that shows great similarities with the South Semitic alphabets.

Ptolemaic hieroglyphic text on the temple of

Kom Ombo

Reconstruction of the evolution of writing. With the hypothesis that the Sumerian

cuneiform script is the origin of many writing systems.

Surname

Unfinished hieroglyphs show the creation process of the incisions with preliminary drawing and execution, 5th Dynasty, around 2400 BC. Chr.

The term "hieroglyphics" is the Germanized form of the ancient Greek ἱερογλυφικὰ γράμματα hieroglyphikà grammata , German , holy character ' or holy notches' which consists ἱερός hieros , German , holy ' and γλύφω glypho , German , (in stone) engrave / carve' , is composed. This name is the translation of the Egyptian zẖ3 nj mdw.w nṯr 'Scripture of God's Words', which indicates the divine origin of the hieroglyphic writing.

history

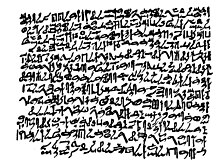

This picture is a good example of the strong imagery with which hieroglyphics were often written.

Early times and origins

According to ancient Egyptian tradition, Thoth , the god of wisdom, created the hieroglyphs. The Egyptians therefore called it "the scriptures of God's words".

The beginnings of this script can be traced back to predynastic times . The question of whether Sumerian cuneiform or Egyptian hieroglyphs represent the earliest human writing, which used to be usually decided in favor of cuneiform script, must again be regarded as open since the possibly oldest known hieroglyphic finds from around 3200 BC. BC ( Naqada III ) in Abydos from the predynastic princely grave U ‑ j came to light. The opinion Guenter Dreyer fully developed hieroglyphs were on little plaques that - attached to vessels - probably marked their origin. Some of the early characters are similar to Sumerian characters. Therefore, a dependency cannot be completely ruled out, but it is also possible in the opposite direction. These questions are controversial.

The hieroglyphic writing apparently began as a notation system for accounting and for the transmission of important events. It was quickly developed further with the content to be communicated and already appears as a finished system in the oldest certificates.

distribution

The Egyptian hieroglyphs were initially mainly used in administration, later for all matters throughout Egypt. Outside of Egypt, this script was only used regularly in the Nubian area, initially during the time of Egyptian rule, later also when this area was independent. Around 300 BC The Egyptian hieroglyphs were replaced here by the Nubians' own script, the Meroitic script , the individual characters of which, however, have their origin in the hieroglyphs. The ancient Hebrew script of the 9th to 7th centuries BC BC used the hieratic numerals, but was otherwise a consonant alphabet derived from the Phoenician script . Most of the communication with the states of the Middle East was in Akkadian cuneiform . It can be assumed that hieroglyphs were much less suitable for reproducing foreign terms or languages than cuneiform.

It is unclear how large the proportion of the Egyptian population were literate, it should have been only a few percent: The term “ writer ” has long been synonymous with “official”. In addition, in Greek times there were demonstrably many full-time scribes in the cities who issued certificates for illiterate people.

Late tradition and decline

From 323 to 30 BC BC the Ptolemies ( Macedonian Greeks ) ruled and after them the Roman and Byzantine empires of Egypt, the administrative language was therefore ancient Greek . Egyptian was only used as the colloquial language of the indigenous population. Nevertheless, the hieroglyphic writing was used for sacred texts and the demotic in everyday life. Knowledge of hieroglyphs was limited to an increasingly narrow circle, but Ptolemaic decrees were often written in hieroglyphs. Ptolemaic decrees contain the provision that they should be published "in hieroglyphics, the writing of the letters (ie: Demotic ) and in the Greek language". At the same time, the characters were multiplied to several thousand without the writing system as such being changed.

Interested Greeks and Romans encountered this script in this form in late antiquity . They took over fragments of anecdotes and explanations for the sound value and meaning of these secret symbols and passed them on to their compatriots.

With the introduction of Christianity, the hieroglyphs were finally forgotten. The last dated inscription, the graffito of Esmet-Achom , dates from 394 AD. The hieroglyphics of the late ancient philosopher Horapollon , which contains a mixture of correct and incorrect information about the meaning of the hieroglyphs , comes from the 5th century AD , by also interpreting phonetic signs as logograms and explaining them through factual correspondences between image and word.

Decipherment

| In the Islamic world, interest in hieroglyphics re-emerged in the 9th century. In the 9th or 10th century , the Iraqi scholar Ibn Wahshiyya tried to interpret several dozen characters and some groups of characters, recognizing that writing has an essential phonetic component and correctly assigned individual phonetic values.

During the Renaissance , an interest in hieroglyphics also arose in Europe. Horapollon's statements misled the efforts of the German Jesuit and polymath Athanasius Kircher and some other scholars. Kircher's attempts to decipher were soon recognized as wrong.

Decisive progress was made possible by the Rosetta Stone , which was found during Napoleon's Egyptian campaign during excavation work near the city of Rosetta . It contains a decree written in Greek, hieroglyphic-Egyptian and demotic from the Ptolemaic period , making it an ideal starting point for further research. In 1802 the Swede Johan David Åkerblad succeeded in deciphering individual demotic words on the Rosetta Stone, in 1814 the English physicist Thomas Young made further progress in understanding the demotic text, and he also recognized the relationship between the demotic and the hieroglyphs. Two years later he discovered their hieroglyphic counterparts for many hieratic symbols. Jean-François Champollion showed using the cartouches for Ptolemy VIII , Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III. that the hieroglyphs also had phonetic symbols. By comparing it with other well-known royal names, especially the names of Roman emperors, Champollion gained the phonetic values of many hieroglyphs. Building on these discoveries, Champollion was able to decipher numerous other characters by comparing Egyptian texts with Coptic, thus opening up the grammar and vocabulary of Egyptian. In 1822, Champollion managed to essentially decipher the hieroglyphs. However, Champollion assumed that the phonetic characters only stood for one consonant. Only with the multi-consonant signs and phonetic complements discovered by Richard Lepsius was it possible to fully decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphic system.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ancient Egyptian writing systems

Depending on the writing material and intended use, different fonts can be distinguished: first the hieroglyphs and an italic variant, the hieratic. Although the characters took on different forms, the functional principle of hieroglyphic writing was preserved. The much younger demotic script is derived from the hieratic script and has little resemblance to the hieroglyphics.

Hieroglyphics

Hieroglyphs are a monumental script designed for use on temple and grave walls . In addition to orthographic aspects, the writing system contains many peculiarities that can only be explained with the ornamental effect, the use of space or magical perspectives. As some particularly well-preserved examples still show - such as the inscriptions in the tombs in the Valley of the Kings - the hieroglyphs were originally written in multiple colors. The color partly corresponded to the natural color of the depicted object, partly it was determined purely conventionally. In individual cases, the color alone could distinguish between two otherwise identical characters; this is especially true of several hieroglyphs with a round outline.

Egyptian words are also written variably within a text. The hieroglyphic writing is hardly a pictorial writing despite the strong imagery (which the Egyptians were aware of) .

Hieratic script

The hieratic script is as old as the hieroglyphic script. It is a cursive variant of hieroglyphic writing, which was designed for writing with a rush on papyrus or similar suitable material (such as ostraka made of limestone or clay). At first it was also used for general texts, religious texts were partly written in hieroglyphics on papyrus in the Middle Kingdom; it was only with the introduction of the demotic as everyday writing that it was limited to the writing of religious texts. This is where the Greek name handed down from Herodotus comes from .

The hieratic depicts the same elements as the hieroglyphs. Because they were written quickly, the characters flowed more often into one another and, in the course of time, became increasingly abstract from the pictorial hieroglyphs; however, the principles of the writing system remained the same. The following table compares some hieroglyphs with their hieratic equivalents:

| Hieroglyphics

|

Hieratic

|

Character number

|

|

|

|

A1

|

|

|

|

D4

|

|

|

|

F4

|

|

|

|

N35

|

|

|

|

V31

|

|

|

|

Z2

|

Italic hieroglyphs

Passage from the

Book of the Dead written in italic hieroglyphics

At the end of the Old Kingdom, a written form split off from the early hieratic that was written on coffins and papyri and, in contrast to the hieratic, adapted to the writing material, but remained close to the hieroglyphic forms. Until the 20th dynasty, religious texts were written in this script, after which it was largely replaced by the hieratic.

Demotic font

Around 650 BC An even more fluid cursive script that was more abstract from the hieroglyphs was developed, the demotic script , also called popular script . It originated as a chancellery script and became a utility script in Egypt until it was used in the 4th / 5th centuries. Century AD was replaced by the Coptic script , a form of the Greek script supplemented by a few demotic characters . Even if the demotic writing shares its basic principles with the hieroglyphs, it can hardly be understood as a subsystem of the hieroglyphs due to major deviations.

The hieroglyphic writing

Direction of writing

The

stele of the Anchefenchon with different directions of writing.

Top right:

from left to right Top left:

from right to left Bottom:

from right to left

Originally the hieroglyphs were usually written in columns (columns) from top to bottom and from right to left, but for graphic reasons the direction of writing could vary. In rare cases hieroglyphics were written as a bustrophedon . The direction of the writing is very easy to determine, as the characters are always facing towards the beginning of the text, ie "looking towards" the reader. This is most evident when depicting animal shapes or people. In individual cases, for example on the inside of coffins, there is retrograde writing, in which the characters are facing the end of the text; this applies, for example, to many manuscripts of the Book of the Dead and could have special religious reasons (Book of the Dead as texts from an "alternative world" or similar).

The word separation was usually not given, but the end of a word can often be recognized by the determinative at the end of the word .

Functions of the characters

| Egyptian hieroglyphs can take on the function of phonograms, ideograms or determinatives . Most hieroglyphs can take on one or a maximum of two of these functions, some even all three. The context shows what function a sign has; in many cases, the uses can hardly be defined. Such is the sign Ideogram in rˁ (w) (sun god) "Re", in the more complete spelling of the same word asit only serves as a determinative; the sign is in the word pr (j) “to go out” is understood as a phonogram pr , while in pr (w) "house" acts as a logogram. Information about whether and how a character can be read is generally provided by Alan Gardiner's list of characters in the Egyptian Grammar , but this is not complete and in individual cases is outdated.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phonograms

| Phonograms are signs that reproduce a certain sound value. As in traditional Arabic or Hebrew, there are basically no characters for vowels , but only characters for consonants . The hieroglyphic Egyptian has characters for individual consonants (so-called single consonant characters ) and characters for sequences of consonants ( multiple consonant characters ), such as the two-consonant character/ w / + / n / wn or the three-consonant sign/ ḥ / + / t / + / p / ḥtp . For the use of a multi-consonant sign, it was irrelevant whether or not there was a vowel between the consonants in the pronunciation of the word.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The sound value of the phonograms is historically related in many, but not in all cases, to the spoken word represented by the respective characters: for example stands for the IPA sound value / r / ( transcription : r ) and represents a mouth, Egyptian r3 . Likewisefor the sound value tp and represents a head, Egyptian tp .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One consonant sign

A simple hieroglyphic alphabet is formed in modern science with a good two dozen characters, each of which reproduces a single consonant, thus representing a kind of "consonantic alphabet". Although the reproduction of Egyptian would have been possible with the single consonant characters, the hieroglyphics were never a pure alphabet. The one-consonant signs are nowadays often used to learn the ancient Egyptian language and to reproduce modern proper names, whereby the modern scientific makeshift pronunciation of the signs is used here, which in many cases is not identical to the original Egyptian sound. For reasons of the history of science, five or six consonants are pronounced as vowels in Egyptological makeshift pronunciation, even though they were used to denote consonants in the classical Egyptian language.

One consonant sign

| character

|

No. in the

Gardiner list

|

Transcriptions

( see below )

|

High German

Egyptian olog ical

Behelfsaussprachen

|

common

Egyptian olog ical

nickname

|

represented object

|

|

|

G1

|

Ꜣ

|

a as in L a nd

|

Aleph

|

egyptian vulture

|

|

|

M17

|

j ( ỉ )

|

ie as in s ie

case by case j as in j a

|

iodine

|

reed

|

|

|

Z4

|

j ( ỉ )

|

ie as in s ie

|

Double line

|

two strokes

|

|

|

2 × M17

|

y

|

ie as in s ie

|

Double reed leaf

|

two reeds

|

or

|

D36

or

2x D36

|

Ꜥ ( ˁ )

|

a as in H a se

or

d as in d u

r as in r ufen

|

Ajin or d / r

|

poor

|

|

or

|

G43 or Z7

|

w

|

u as in H u t,

occasionally w as in English: w aw!

|

Waw

|

Quail chicks

or adaptation of the hieratic abbreviation

|

|

|

D58

|

b

|

b as in B and

|

b

|

leg

|

|

|

Q3

|

p

|

p as in Hu p e

|

p

|

Stool or mat made of reed

|

|

|

I9

|

f

|

f as in F eld

|

f

|

Horned viper

|

|

|

G17

|

m

|

m as in M utter

|

m

|

owl

|

|

|

N35

|

n

|

n as in n a

|

n

|

rippled water

|

|

|

D21

|

r

|

r in r Ufen

|

r

|

mouth

|

|

|

O4

|

H

|

h as in H ose

|

H

|

court

|

|

|

V28

|

H

|

h as in H ose

|

h-with-period,

emphatic h

|

wick

|

|

|

Aa1

|

H

|

ch as in Da ch

|

h-with-bow

|

Well shaft

|

|

|

F32

|

H

|

ch as in i ch

|

h-dash

|

Animal belly with a tail

|

|

|

O34

|

z

|

s as in S and

|

Latch-s

|

Door latch .

|

|

|

S29

|

s

|

ß in Fu ß

|

s

|

folded fabric

|

|

|

N39

|

š

|

sch as in sch ießen

|

Shin

|

pond

|

|

|

N29

|

q

|

k as in K ind

|

Qaf ,

emphatic k

|

slope

|

|

|

V31

|

k

|

k as in K ind

|

k

|

Basket with handle

|

|

|

W11

|

G

|

g as in g ut

|

G

|

Pitcher rack

|

|

|

V33

|

g ( g 2 )

|

g as in g ut

|

|

Burlap sack

|

|

|

X1

|

t

|

t as in T ante

|

t

|

Loaf of bread

|

|

|

V13

|

ṯ

|

Tsch as in Qua Tsch

|

ch

|

Rope

|

|

|

D46

|

d

|

d as in d u

|

d

|

hand

|

|

|

I10

|

ḏ

|

dsh in Dsch ungel

|

dsch

|

cobra

|

Multi-consonant characters

| Most multi-consonant characters are two-consonant characters, for example: ḥr , jr and nw .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A few multi-consonant signs can represent several different sound components, for example: , which - depending on the word - can stand for 3b or mr . The intended sound stock is usually unambiguated by so-called phonetic complements , which are also often used in unambiguous cases: this is how 3b becomes common 3b-b written, but the transcription is only 3b ; mr howeverm-mr-r or more aesthetic mr-mr, the transcription is also just mr . But also the unambiguous mn will almost alwayswritten mn-n ( mn ). If the ambiguous multi-consonant sign is not disambiguated by such single consonant signs, the reading generally results from the context.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In some cases, characters for more than two consonants are difficult to distinguish from the logograms (see below), for example the character comes , which corresponds to the consonant sequence sḫm , only in words that are etymologically related to the terms “power” / “mighty” / “become mighty” (Egypt. sḫm ). It can therefore just as easily be understood as a logogram.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Logograms and ideograms

|

Ideograms (word signs) stand for a certain word or a word stem. The function of a sign as a logogram / ideogram is often referred to by means of a so-called ideogram lineexplicitly pointed out. Often, but not always, there is an obvious connection between the object depicted and the word labeled with the logogram. This is the sign, which represents a house floor plan, in the spelling for "house" (Egyptian: prw ) and the symbol, which represents the sun, in spelling for the word for the sun god, Re ( rˁw ). However, the number of words written with such characters is small, the majority of words were written with phonograms; the logographic spelling declined more and more from the Old Kingdom onwards and was often replaced by phonetic spellings with determinatives. Especially since the New Kingdom, the logogram line has also been used in the hieratic after signs of other functions (especially for determinatives).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Determinative

Since only the consonants, not the vowels, were referred to with hieroglyphics, there were many words with different meanings that were spelled the same, because they had the same consonants. The determinative originally embodied the phonograms on which it was based as a pictorial unifying character. Only later was the determinative to be combined with other general terms. So-called determinants (also classifiers or Deutzeichen) were added to most words, which explain the meaning in more detail. The hieroglyph “house” with the consonant pr without determinative means the word “house” (Egyptian pr (w) ), with two running legs as a determinative it means “going out” (Egyptian pr (j) ). Names were also determined, as were some pronouns . The names of kings or gods were emphasized by the cartouche , a loop around the word.

The following table lists some words that all have the consonant stock wn and can only be differentiated by their determinative:

Determinative

hieroglyphic

writing

|

modern

Egyptian olog ical

transcription

|

Word meaning

|

object represented

by the determinative |

Meaning of the

determinative

|

|

|

wn

|

to open

|

Door leaf

|

Gate / door / gate u. Ä .;

to open

|

|

|

wn (j)

|

rush

|

Pair of legs

|

Move

|

|

|

wn

|

Error; Fault; Rebuke

|

Sparrow, sparrow, etc.

|

bad, bad, inadequate, etc. Ä .;

Bad, evil, inadequate

|

|

|

wn

|

bald

|

Tufts of hair

|

Hair, hairy;

Sadness, sad

|

It should be noted, however, that the system of determinants in the course of Egyptian linguistic history only fully stabilized in the Middle Kingdom , while Egyptian of the Old Kingdom used even more special or ad hoc determinatives. In the New Kingdom the use of less, particularly generic, determinants increased; sometimes a word could be written here with several determinants at the same time.

Further examples of determinatives are:

| Woman, female

|

child

|

man

|

king

|

Requiring strength

|

Move

|

Things made of wood

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phonetic determinants

| Occasionally, determinatives and the preceding phonograms were apparently perceived as a unit, so that in rare cases determinatives were dragged along with phonograms to other words with the same phonetic structure, for example , the end jb "buck" came from the word jb (j) "to be thirsty". New phonograms could also arise from such spellings, such as, the end tr "time" originated, among other things in the particles tr and eventually became a separate phonogram tr . The logogram was used as a kind of "phonetic ideogram" in nˀ.t "city" for example in or ḥn.t (possibly hence ḥnˀ.t to read) "Pelikan" used.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calligraphic peculiarities

arrangement

In hieroglyphic inscriptions, the characters were usually not simply strung together, but combined into rectangular groups. The word sḥtp.n = f "he satisfied" was written as follows in the Middle Kingdom:

This is read from top to bottom and left to right in the following order:

| Some characters were exchanged so that there was no gap; in other cases, two characters were swapped in order to use the space optimally and to avoid irritating gaps: instead of . In particular, signs with a free space behind them allow the following sign to appear in front of them:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

instead of the very rare 3ḥ.t "field". Out of awe, certain words were always put in front of the scriptures: Ḫˁj = f-Rˁ " Chafre " where the sign, which stands for the sun god Re, although it was only at the end of the name in the spoken form.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suppression and mutilation of characters

| In religious texts in particular, hieroglyphs depicting living beings were often left out or mutilated, cf. in the pyramid texts (Pyr. § 382 b) instead of anything else ḥqr “starve”. Often people only wrote the upper body with the head, animals, on the other hand, were often crossed out; Another possibility was to replace determinatives, which represented a living being, with a substitute symbol, mostlywhich later appeared in the Hieratic for all determinatives that were difficult to draw.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Group writing

| Group writing or syllabic writing refers to a special use of hieroglyphs, which can already be found to some extent in the Old Kingdom, but was only used in full in the New Kingdom, especially for foreign words and individual Egyptian words. In contrast to the normal use of hieroglyphs, group spellings, according to the interpretation of some scholars, indicate vowels. Groups of one to three hieroglyphs represent a whole syllable, whereby these syllable groups partly consist of one- and two-consonant characters, partly of one- or two-consonant words (like j "oh" for "ˀa" or similar). The extent to which the group writing enables clear vocal readings is not entirely clear. W. Schenkel and W. Helck, for example, advocate the theory that only the vowels i and u , but not a , could be reproduced unambiguously. An example is the hieroglyphic spelling of the name of the Cretan city of Amnissos :. If one were to read the hieroglyphs according to their normal sound value, one would get jmnyš3 , according to the generally accepted research opinion this stands in the group writing for the consonant sequence ˀ-mn-š ; According to Schenkel and Helck, this reading can be specified as ˀ (a) -m (a) -ni-š (a) . Even if in cases like this the assumption of a clear reproduction of the vowels seems plausible, the amount of material has not yet made a clear decision possible. The writing of foreign words with group writing has parallels in other writing systems; In Japanese there is a special syllabar ( katakana ) for the notation of words from foreign languages .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Numeral

pronunciation

Since the hieroglyphic writing a language is one whose descendant of the 17th century with displacement of Coptic as the latest official language is dead by the Arab and listed no vowels in hieroglyphic writing, is the reconstruction of the Egyptian words and the transcription hieroglyphic names and words in modern alphabets are ambiguous. This is how the very different spellings of the same name come about, such as Nefertiti in German and Nefertiti in English for Egyptian Nfr.t-jy.tj . In addition to the Coptic and the hieroglyphic spellings themselves, the controversial Afro-Asian phonetic correspondence and ancillary traditions such as Greek and cuneiform paraphrases give indications of the pronunciation of Egyptian names and words. The original Coptic resulting from these traditions , a language with hieroglyphic consonants and reconstructed vowels, has been taken up in various films (mostly with dubious results), including for the film The Mummy and the Stargate series .

Egyptologists make do with the pronunciation of Egyptian by inserting an e between many consonants in the transcribed text and pronouncing some consonants as vowels ( 3 and ˁ as a , w as w or u , j and y as i ). That is the rule, but not without exception; as king and God's name be pronounced according to traditional Greek or Coptic spellings, for example, such as " Amen " instead of "imenu" for Egyptian Jmn.w . In particular, different conventions have developed at the individual universities on how Egyptological transliteration is to be pronounced as an alternative. The word nfrt (feminine from nfr : "beautiful") can be found both as neferet (so often in Germany) as well as nefret (elsewhere in Germany) or as nefert (so among other things at Russian universities). There are also systematic differences in the length or shortness of the e s and the word accent.

transcription

| When translating hieroglyphic texts, a transcription in Egyptological transcription is often made, in which the hieroglyphic writing is converted into the corresponding sounds. The purpose of the transcription is to use a typographically simpler writing system to understand how to read the hieroglyphic text. Since the Egyptological transcription systems only reproduce sounds and word structure features - and in particular no determinatives - this process is only unambiguous in one direction. This means that hieroglyphic representations can no longer be recovered from a text in Egyptological transcription, although suggestions have been made for a clear reproduction of the hieroglyphs in accordance with the system used in cuneiform writing. Different systems are used for the transcription, which however do not differ fundamentally, only in the visual design of the transcription marks. For example, the sound indicated by the hieroglyphis reproduced (mostly interpreted as IPA / tš /), depending on the transcription system either ṯ (so since the "Berlin School" Adolf Ermans ) or more recently by some of the scholars č (especially the "Tübingen School" Wolfgang Schenkel ). On the Internet and for character assignments in fonts, the encoding of the transcription according to "Manuel de Codage" is common.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transcription systems of important Egyptological works

Transcription

variants

|

Peust

phono

logy

|

Allen

Middle

Egyptian

|

Loprieno

Ancient

Egyptian

|

Hannig

GHWb. ;

Wikipedia

|

Noble

Altägy.

Size

|

Erman

& Grapow

Wb.

|

Malaise

& Winand

Gr.

|

Gardiner

Egyptian

Gr.

|

Schenkel

Tübing.

Easy

|

Corresponding one-

consonant

sign

|

Manuel

de Codage

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

so-called secondary aleph

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A.

|

|

ỉ ~ j

|

j

|

j

|

j

|

j

|

j

|

ỉ

|

ỉ

|

ỉ

|

ỉ

|

|

i

|

|

ỉ ~ j ~ i̯

|

i̯

|

j

|

j

|

j

|

j

|

j

|

ỉ

|

ỉ

|

i̯

|

Final consonant of weak verbs

|

|

|

j ~ y ~ ï

|

ï

|

y

|

j ~ y

|

j

|

j

|

j

|

y

|

y

|

ï

|

|

y

|

|

j ~ jj ~ y

|

y

|

y

|

j ~ y

|

y

|

y ~ yy

|

j

|

j

|

y

|

y

|

|

i * i

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a

|

|

w

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

or

|

w

|

|

w ~ u̯

|

u̯ (?)

|

w (?)

|

w (?)

|

w (?)

|

w (?)

|

w (?)

|

w (?)

|

w (?)

|

u̯

|

Final consonant of weak verbs

|

|

|

b

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

b

|

|

p

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

p

|

|

f

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

f

|

|

m

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

m

|

|

n

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

n

|

|

r

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r

|

|

l

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

different

|

l

|

|

H

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

H

|

|

H

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

H

|

|

H

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x

|

|

H

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

s ~ z

|

z

|

z

|

z

|

s (z)

|

z

|

s

|

s

|

s

|

s

|

|

z

|

|

ś ~ s

|

s

|

s

|

s

|

s

|

s

|

ś

|

ś

|

s (ś)

|

ś

|

|

s

|

|

š

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S.

|

|

ḳ ~ q

|

q

|

q

|

q

|

q

|

q

|

ḳ

|

ḳ

|

ḳ

|

ḳ

|

|

q

|

|

k

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

k

|

|

G

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G

|

|

t

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t

|

|

ṯ ~ č

|

ṯ

|

ṯ

|

ṯ

|

ṯ

|

ṯ

|

ṯ

|

ṯ

|

ṯ

|

č

|

|

T

|

|

d ~ ṭ

|

d

|

d

|

d

|

d

|

d

|

d

|

d

|

d

|

ṭ

|

|

d

|

|

ḏ ~ č̣

|

ḏ

|

ḏ

|

ḏ

|

ḏ

|

ḏ

|

ḏ

|

ḏ

|

ḏ

|

č̣

|

|

D.

|

In addition to the phonetic transcription characters, most transcription systems also contain so-called structural characters, which separate morphemes from one another in order to clarify the morphological structure of the words. For example, certain researchers transcribed the ancient Egyptian verb form jnsbtnsn "those who devoured them" as j.nsb.tn = sn in order to identify the various prefixes and suffixes . The use of structural characters is even less uniform than the phonetic transcriptions - in addition to systems without any structural characters, such as the one used in Elmar Edel's Ancient Egyptian Grammar (Rome 1955/64), there are systems with up to five structural characters ( Wolfgang Schenkel ) . Individual characters are not used uniformly either; The simple point (“.”) in the romanization of the Berlin School serves to separate the suffix pronouns, in some more recent systems it is used to mark the nominal feminine ending. While James P. Allen separates a prefix j of certain verb forms with a single point, Wolfgang Schenkel proposed the colon (“:”) for this.

Hieratic texts are often converted into hieroglyphs ( transliteration ) and published in such a way that the characters can be identified with the corresponding hieroglyphs before they are transcribed . The identification of the italic characters can only be carried out by specialists and is not easy to understand by everyone familiar with hieroglyphic writing. Demotic texts, on the other hand, are usually not transliterated first, because the distance to the hieroglyphs is too great, but transcribed directly into transcription.

The meanings of the terms “transcription” and “transliteration” are inconsistent; In some Egyptian grammars, especially in English, the terms transcription and transliteration are used the other way around.

Hieroglyphs in word processing

Reproduction of hieroglyphics

Hieroglyphs are encoded in the Unicode block Egyptian hieroglyphs (U + 13000 – U + 1342F), which is covered, for example, by the Segoe UI Historic font supplied with Windows 10 and higher .

In addition, there are a number of hieroglyphic word processing programs that use a system for coding the hieroglyphs using simple ASCII characters, which at the same time depicts the complicated arrangement of the hieroglyphs. The individual hieroglyphs are coded either using the numbers in the Gardiner list or their phonetic values. This method is called Manuel de Codage format, or MdC for short, after its publication. The following excerpt from a stele from the Louvre (Paris) provides an example of the coding of a hieroglyphic inscription :

sw-di-Htp:t*p i-mn:n:ra*Z1 sw-t:Z1*Z1*Z1 nTr ir:st*A40

i-n:p*w nb:tA:Dsr O10 Hr:tp R19 t:O49 nTr-nTr

Hr:Z1 R2 z:n:Z2 Szp:p:D40 z:n:nw*D19:N18 pr:r:t*D54

Stele from the

Louvre (reversed to the examples on the left)

In order to create a lifelike image of the arrangement of the hieroglyphs, complex hieroglyphic typesetting programs must offer not only the overlap-free arrangements, but also a function of mirroring hieroglyphs, changing their size continuously and arranging individual characters partially or completely one above the other (see the sequence of characters at the bottom right in the picture, which could not be implemented here).

For playback and set of hieroglyphics on the computer a number of programs has been developed. These include SignWriter , WinGlyph , MacScribe , InScribe , Glyphotext, and WikiHiero .

Reproduction of transcription marks

Special fonts are required to reproduce the Egyptological transcription on the computer, as certain transcription characters are missing in standard fonts. A distinction must be made between non-Unicode fonts and Unicode fonts.

Traditionally

In addition to all sorts of private fonts, the TrueType fonts "Transliteration" by CCER and "Trlit_CG Times" are particularly widespread in science , in which the transcription system of the dictionary of the Egyptian language by Erman and Grapow and Alan Gardiner's Egyptian Grammar largely precisely matches the keyboard layout des Manuel de Codage (see above). The journal Lingua Aegyptia provides a character set by the Egyptologist Friedrich Junge , with which all common transcription systems can be reproduced, but which differs from Manuel de Codage in terms of keyboard layout (Umschrift_TTn).

Unicode

Alef, Ajin and, since March 2019, iodine have now been included in the Unicode standard ( Unicode block Latin, extended-D ).

Special transcription characters in Unicode

| Minuscule

|

ʾ (  ) )

|

ꜣ (  ) )

|

ꞽ (  ) )

|

i̯

|

ï

|

ꜥ (  ) )

|

u̯

|

H

|

H

|

H

|

H

|

| Unicode

|

U + 02BE

|

U + A723

|

U + A7BD

|

'i'

& U + 032F

|

U + 00EF

|

U + A725

|

'u'

& U + 032F

|

U + 1E25

|

U + 1E2B

|

U + 1E96

|

'h'

& U + 032D

|

| Capitals

|

|

Ꜣ

|

Ꞽ

|

|

|

Ꜥ

|

|

H

|

H

|

H

|

H

|

| Unicode

|

|

U + A722

|

U + A7BC

|

|

|

U + A724

|

|

U + 1E24

|

U + 1E2A

|

'H'

& U + 0331

|

'H'

& U + 032D

|

| Minuscule

|

ś

|

š

|

ḳ

|

č

|

ṯ

|

ṭ

|

ṱ

|

č̣

|

ḏ

|

|

|

| Unicode

|

U + 015B

|

U + 0161

|

U + 1E33

|

U + 010D

|

U + 1E6F

|

U + 1E6D

|

U + 1E71

|

U + 010D

& U + 0323

|

U + 1E0F

|

|

|

| Capitals

|

Ś

|

Š

|

Ḳ

|

Č

|

Ṯ

|

Ṭ

|

Ṱ

|

Č̣

|

Ḏ

|

|

|

| Unicode

|

U + 015A

|

U + 0160

|

U + 1E32

|

U + 010C

|

U + 1E6E

|

U + 1E6C

|

U + 1E70

|

U + 010C

& U + 0323

|

U + 1E0E

|

|

|

| Brackets / punctuation

|

⸗

|

〈

|

〉

|

⸢

|

⸣

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Unicode

|

U + 2E17

|

U + 2329

|

U + 232A

|

U + 2E22

|

U + 2E23

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The coding with U + A7BD (Egyptological yod) is supported by the font New Athena Unicode .

Since the iodine, which was only added in March 2019, has not yet been implemented in many fonts, various workarounds have been and are used for this :

Workarounds for Egyptological iodine

| designation

|

Capital letter

|

Lowercase letter

|

| Right half ring above

|

I͗

U + 0049 U + 0357

|

i͗

U + 0069 U + 0357

|

ı͗

U + 0131 U + 0357

|

| I with hook above

|

Ỉ

U + 1EC8

|

ỉ

U + 1EC9

|

| Cyrillic psili pneumata

|

I҆

U + 0049 U + 0486

|

i҆

U + 0069 U + 0486

|

| Superscript comma

|

I̓

U + 0049 U + 0313

|

i̓

U + 0069 U + 0313

|

The coding with U + 0357 (right half ring above) is supported by the Junicode and New Athena Unicode fonts .

The historical writing practice

Writing media

The Egyptians used stone, clay and rolls made of papyrus , leather and linen as writing media , which they occasionally decorated with artistically colored pictures. The scribe's tools were:

- a mostly wooden case with several writing tubes that were either hammered flat at the end or cut at an angle,

- a plate as a base and to smooth the papyrus,

- a supply of black ink (made from carbon black powder, gum arabic is used as a binding agent),

- and one with red ink for titles, headings and chapter beginnings (see rubrum ), but not for god names (made of vermilion powder , a mercury - sulfur compound or lead oxide),

- a keg for water with which the ink is mixed and

- a knife for cutting the papyrus.

The longest preserved papyrus measures 40 meters. Leather was mainly used for texts of great importance.

The job of the writer

Knowing the letter was certainly a prerequisite for any career in the state. There was also no separate name for the official - “sesch” means both “scribe” and “official”. Surprisingly little is known about the school system. For the old empire, the family system is adopted: Pupils learned to write from their parents or were placed under another clerk who first used the pupils for auxiliary work and also taught them to write. From the Middle Kingdom onwards, there are isolated documents for schools that are well attested to from the New Kingdom. The training to become a scribe began with one of the cursive scripts (hieratic, later demotic). The hieroglyphs were learned later and, due to their nature as monumental script, not every scribe could master them. Scripture was mainly taught through dictation and transcription exercises, preserved in some cases, while lazy students were disciplined through punishment and imprisonment.

The book Kemit comes from the Middle Kingdom and was apparently written specifically for school lessons. The teaching of the Cheti describes the advantages of the writing profession and enumerates the disadvantages of other, mostly manual and agricultural professions.

literature

(sorted chronologically)

- Introductions

- WV Davies: Egyptian Hieroglyphs . 5th imprint. British Museum Press, London 1992, ISBN 0-7141-8063-7 , ( Reading the past ).

-

Karl-Theodor Zauzich : Hieroglyphics without a secret. An introduction to the ancient Egyptian script for museum visitors and Egypt tourists (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 6). Published by the Association for the Promotion of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin-Charlottenburg eV 11th edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-0470-6 ( ISSN 0937-9746 ).

- Marc Collier, Bill Manley: Hieroglyphics. Decipher, read, understand . Knaur, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-426-66425-9 , (Original edition: How to read Egyptian hieroglyphs . British Museum Press, London 1998, ISBN 0-7141-1910-5 ).

-

Gabriele Wenzel : Hieroglyphics. Write and read like the pharaohs . 3rd edition, Nymphenburger, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-485-00891-5 .

- Bridget McDermott: deciphering hieroglyphics. Read and understand the secret language of the pharaohs. Area, Erftstadt 2006, ISBN 978-3-89996-714-2 .

- Petra Vomberg, Orell Witthuh: Hieroglyphic key . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-447-05286-3 .

-

Hartwig Altenmüller : Introduction to hieroglyphic writing (= introductions to foreign scripts. ) 2nd, revised and expanded edition, Buske, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-87548-535-6 .

-

Michael Höveler-Müller : Reading and writing hieroglyphs. In 24 easy steps . Beck, Munich 2014. ISBN 978-3-406-66674-2 .

- Decipherment

- Lesley Adkins, Roy Adkins: The Code of the Pharaohs . Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2002, ISBN 3-7857-2043-2 .

- Markus Messling: Champollion's hieroglyphs, philology and appropriation of the world . Kadmos, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86599-161-4 .

- Grammars with character lists

-

Adolf Erman : New Egyptian grammar. 2nd completely redesigned edition. Engelmann, Leipzig 1933, (comprehensive presentation of the peculiarities of the new Egyptian spellings: §§ 8–42).

- Herbert W. Fairman: An Introduction to the Study of Ptolemaic Signs and their Values. In: Le Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale. No. 43, 1945, ISSN 0255-0962 , pp. 51-138.

-

Alan Gardiner : Egyptian Grammar. Being an introduction to the study of hieroglyphs. Third edition, revised. Oxford University Press, London 1957, (First: Clarendon Press, Oxford 1927), (Contains the most detailed version of the Gardiner list , the standard hieroglyphic list, as well as an extensive representation of the writing system).

-

Elmar Edel : Ancient Egyptian grammar (= Analecta Orientalia, commentationes scientificae de rebus Orientis antiqui. Vol. 34/39). Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, Rome 1955–1964, (In §§ 24–102 it offers a very extensive description of the rules of writing and the principles of hieroglyphics), (Also published: Register of quotations . Edited by Rolf Gundlach. Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, Rome 1967) .

-

Jochem Kahl : The system of the Egyptian hieroglyphic writing in the 0–3. Dynasty. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-447-03499-8 , (= Göttinger Orientforschungen. Series 4: Egypt. 29, ISSN 0340-6342 ), (also: Tübingen, Univ., Diss., 1992).

- James P. Allen: Middle Egyptian. An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge 2000, ISBN 0-521-77483-7 , (teaching grammar with exercise texts, also goes into detail on the cultural context of the texts).

- Pierre Grandet, Bernard Mathieu: Cours d'égyptien hiéroglyphique. Nouvelle édition revue et augmentée, Khéops, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-9504368-2-X .

-

Friedrich Junge : Introduction to the grammar of New Egyptian. 3rd improved edition. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-447-05718-9 , (on writing materials, transcription and transliteration §§ 0.3 + 0.4; on the peculiarities of the New Egyptian spelling § 1).

- Daniel A. Werning: Introduction to the hieroglyphic-Egyptian script and language. Propaedeutic with drawing and vocabulary lessons , exercises and exercise tips , 3rd verb. Edition, Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin 2015. doi : 10.20386 / HUB-42129 .

- Digital introductory grammars online

- Character lists

- Ferdinand Theinhardt: List of the hieroglyphic types from the font foundry of Mr. F. Theinhardt . Academy of Sciences, Berlin 1875.

-

Rainer Hannig : Large concise dictionary of Egyptian-German. (2800-950 BC). The language of the pharaohs. Marburg Edition. 4th revised edition. von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , (= Hannig-Lexica. Vol. 1); (= Cultural History of the Ancient World . Vol. 64, ISSN 0937-9746 ), (Contains the Gardiner list and an extended list of characters).

-

Rainer Hannig , Petra Vomberg: Vocabulary of the Pharaohs in subject groups. Hannig Lexica Vol. 2 , 2nd edition, von Zabern, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4473-9 .

-

Wolfgang Kosack : Egyptian list of characters I. Basics of hieroglyphic writing. Definition, design and use of Egyptian characters. Preparatory work on a font list. Christoph Brunner, Basel 2013, ISBN 978-3-9524018-0-4 .

-

Wolfgang Kosack : Egyptian list of symbols II. 8500 hieroglyphs of all epochs. Readings, interpretations, uses collected and processed. Christoph Brunner, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9524018-2-8 .

- Others

-

Christian Leitz : The temple inscriptions of the Greco-Roman times. 3rd improved and updated edition. Lit, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-8258-7340-0 , (= source texts on Egyptian religion. Vol. 1), (= introductions and source texts on Egyptology. Vol. 2), (with references to older lists of Ptolemaic hieroglyphs ). Content (PDF; 230 KB) .

-

Siegfried Schott : Hieroglyphs. Investigations into the origin of writing. Verlag der Wissenschaften und der Literatur in Mainz (commissioned by Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden), Mainz 1950 (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences and Literature. Humanities and social science class. Born 1950, volume 24).

Web links

Individual evidence

-

↑ Jan Assmann : Stone and Time: Man and Society in Ancient Egypt . Fink, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7705-2681-3 . P. 80.

-

↑ The number of Ptolemaic symbols is considered by Leitz, 2004, to be considerably lower.

-

↑ Jochem Kahl: From h to q. Evidence for an "alphabetical" sequence of single-consonant sound values in late-period papyri . In: Göttinger Miscellen . (GM) Volume 122, Göttingen 1991, pp. 33-47, ISSN 0344-385X .

-

^ Geoffrey Barraclough, Norman Stone: The Times Atlas of World History. Hammond Incorporated, Maplewood, New Jersey 1989, ISBN 978-0-7230-0304-5 , p. 53. ( [1] on archive.org)

-

^ Günter Dreyer: Umm el-Qaab I, The predynastic royal grave Uj and his early written documents . von Zabern, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-8053-2486-3 .

-

^ Francis Amadeus Karl Breyer: The written testimonies of the predynastic royal tomb Uj in Umm el-Qaab: attempt at a new interpretation. In: The Journal of Egyptian Archeology. No. 88, 2002, pp. 53-65.

-

↑ Aḥmad ibn ʻAlī Ibn Waḥshīyah: Ancient Alphabets and Hieroglyphic Characters Explained. (Original: Shauq al-mustahām fī maʻrifat rumūz al-aqlām ). Edited and translated by Joseph Hammer-Purgstall. London, 1806, pp. 43-51. On archive.org : http://archive.org/details/ancientalphabet00conggoog , http://archive.org/details/ancientalphabet00hammgoog

-

↑ Arabic Study of Ancient Egypt ( Memento from February 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

-

↑ Simon Singh : Secret Messages . The art of encryption from ancient times to the Internet. dtv 2005, pp. 247-265.

-

↑ Nadine Gola, Heinz-Josef Thissen: Deciphering and systematizing the hieroglyphs. lepsius online, archived from the original on May 4, 2014 ; accessed on December 16, 2018 .

-

^ Richard Lepsius: Lettre à M. Rosellini sur l'alphabet hiéroglyphique. Rome 1837.

-

^ A. Gardiner: Egyptian Grammar: Being an introduction to the study of hieroglyphs. Oxford 1927.

-

↑ For possible exceptions, see: Wolfgang Schenkel: Rebus, spelling syllables and consonant writing . In: Göttinger Miscellen. Volume 52, Göttingen 1981, pp. 83-95.

-

^ Daniel A. Werning endorses the reading dp : The Sound Values of the Signs Gardiner D1 (Head) and T8 (Dagger) (PDF; 682 kB) , In: Lingua Aegyptia . No. 12, 2004, pp. 183-203

-

↑ according to Erik Hornung : Introduction to Egyptology. Was standing ; Methods; Tasks. 7th, unchanged edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-23641-1 , p. 22f.

-

↑ a b c From the Old Kingdom through the Middle Kingdom to the Second Intermediate Period ; see. Alexandra von Lieven : Cryptography in the Old and Middle Kingdom . In: Alexandra von Lieven: Plan of the course of the stars - The so-called groove book . The Carsten Niebuhr Institute of Ancient Eastern Studies (among others), Copenhagen 2007, ISBN 978-87-635-0406-5 . P. 32.

-

↑ Wolfgang Schenkel: Glottalized plosives, glottal plosives and a pharyngeal fricative in Coptic, conclusions from the Egyptian-Coptic loanwords and place names in Egyptian-Arabic. In: Lingua Aegyptia. No. 10, Göttingen 2002, pp. 1–57, especially p. 32 ff. ISSN 0942-5659 ( online )

-

↑ mḥr after Joachim Friedrich Quack: On the sound value of Gardiner Sign List U 23 . In: Lingua Aegyptia. No. 11, Göttingen 2003, pp. 113-116. ISSN 0946-8641

-

↑ See Daniel A. Werning. May 14, 2018. "§8", digital introduction to hieroglyphic Egyptian writing and language, Humboldt University Berlin, http://hdl.handle.net/21.11101/0000-0007-C9C9-4?urlappend=index.php?title= % C2% A78% 26oldid = 168 .

-

↑ So the reading by E. Edel: Ancient Egyptian Grammar. S. 605. Cf. but: njw.t in A. Gardiner: Egyptian Grammar. Oxford 1927, p. 498 and based on it Hannig: Handwörterbuch. P. 414.

-

↑ The cited writings for "Pelikan" come from the Pyramid Texts , § 278 b , or the Ebers papyrus ( note )

-

^ P. Lacau: Suppressions et modifications de signes dans les textes funéraires . In: Journal of Egyptian Language and Antiquity . Leipzig 1914, No. 51, p. 1 ff. (Reprint Biblio, Osnabrück 1975), ISSN 0044-216X .

-

↑ Wolfgang Helck : The relations of Egypt to the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC BC Egyptological treatises. Vol. 5. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1971 (2nd edition), pp. 505-575. ISBN 3-447-01298-6

-

^ E. Edel: Ancient Egyptian grammar . Section 103; Wolfgang Schenkel: From the work on a concordance on the ancient Egyptian coffin texts . Göttingen Orient Research. 4th row. Vol. 12. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 3-447-02335-X .

-

^ Carsten Peust: Egyptian phonology: an introduction to the phonology of a dead language (= monographs on the Egyptian language. Volume 2). Peust & Gutschmidt, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3-933043-02-6 .

-

↑ documented in: Pyramid Texts , § 98 c

-

↑ Wolfgang Schenkel: Tübingen Introduction to the Classical Egyptian Language and Script. Tübingen 1997, § 2.2 c

-

↑ Jan Buurman, Nicolas Grimal among others: Inventaire des signes hiéroglyphiques en vue de leur saisie informatique: manuel de codage des textes hiéroglyphiques en vue de leur saisie sur ordinateur. Informatique et Egyptology. Vol. 2. De Boccard, Paris 1988.

-

↑ Available on the Lingua Aegyptia homepage from http://www.gwdg.de/~lingaeg/lingaeg-stylesheet.htm#transliteration .

-

↑ Trlit_CG Times

-

↑ Available on the Lingua Aegyptia homepage from http://www.gwdg.de/~lingaeg/lingaeg-stylesheet.htm#Umschrift_TTn .

-

↑ Unicode 12.0.0 http://unicode.org/versions/Unicode12.0.0/ .

-

↑ New Athena Unicode, v5.007, Dec. 8. 2019, https://apagreekkeys.org/NAUdownload.html

-

↑ Supported by the Junicode and New Athena Unicode fonts [2]

-

↑ Glossing Ancient Languages contributors, “Unicode,” in: Glossing Ancient Languages, ed. Daniel A. Werning (Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 6 July 2018, 07:57 UTC), https: //wikis.hu-berlin .de / interlinear_glossing / index.php?title= Unicode&oldid=1097 (accessed July 6, 2018).

-

↑ See IFAO - Polices de caractères http://www.ifao.egnet.net/publications/publier/outils-ed/polices/ .

-

^ H. Brunner: School . In: Lexicon of Egyptology . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1984, column 741-743, ISBN 3-447-02489-5 .