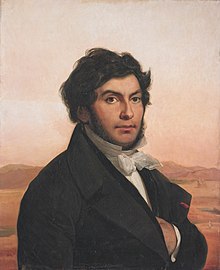

Jean-François Champollion

Jean-François Champollion (born December 23, 1790 in Figeac in the Lot department , † March 4, 1832 in Paris ) was a French linguist . With the deciphering of the first hieroglyphs on the stone of Rosetta , he laid the foundation for the scientific research of dynastic Egypt.

Life

Training in eight foreign languages

Jean-François Champollion was born the son of the bookseller Jacques Champollion. The unrest of the French Revolution prevented regular training.

In March 1801 (at the age of 11) Champollion moved to Grenoble to live with his brother Jacques-Joseph , who later became a professor of ancient Greek , where he continued to receive private lessons and developed a passion for Egypt . With him, all of France was interested in it at the time, due to Napoleon Bonaparte's returning Egyptian expedition .

In 1802 Champollion met the mathematician Joseph Fourier, who had returned from Egypt and was appointed prefect of the Isère department . He showed him parts of his Egyptian collection and, with the declaration that no one could read these characters, woke Champollion's lifelong quest to decipher the hieroglyphs .

At 13, Champollion began learning various oriental languages , and at 17, he successfully gave a lecture on the similarities between Coptic and hieroglyphics. In self-study and with the help of a private teacher, he acquired further excellent language skills and already mastered eight old languages at the age of 18. Apart from a few trips to Italy and the great Egyptian expedition, the researcher lived alternately in Grenoble and Paris.

From November 1804 to August 1807, Champollion attended the newly opened Lyceum and continued to pursue his own language studies there despite the strictly prescribed curriculum. In terms of health, he was not very robust. Even at a young age, he suffered from severe headaches, dry coughs and shortness of breath. He suffered from nervous exhaustion and often passed out. Constant reading in dim lighting attacked his eyesight . Later came tuberculosis , gout , diabetes , kidney and liver damage . Still, the obsessed scholar coped with a tremendous amount of work and rarely allowed himself a break.

After finishing school in August 1807, Champollion presented his essay on the geographical description of Egypt before the conquests by Cambyses and was appointed a member of the Academy of Grenoble. From 1807 to 1809 he studied in Paris, where he expanded his already extensive language skills to include Arabic , Persian and Coptic .

Rosette stone

In Paris, Champollion also worked with the Rosette stone for the first time and derived an alphabet of the demotic from it. The alphabet obtained in this way helped him to decipher non- hieratic papyri , although he was not yet aware of the actual differences at the time.

In 1810 Champollion became professor of ancient history in Grenoble on a shared post at the newly opened university . In the years that followed, his work on hieroglyphs was hindered mainly by a lack of materials, the confusion of the readmission of France by the royalists and the resulting exile in Figeac from March 1816 to October 1817.

Back in Grenoble he took over two schools and married Rosine Blanc in December 1818. Tired of political intrigues and deprived of his offices, he returned to Paris in July 1821. There he mainly concentrated on translations between demotic, hieratic and hieroglyphics. For a long time Champollion had to endure injustices and the envy of his colleagues, but his strong character never let him lose sight of the goal of being the first to decipher the ancient Egyptian characters.

Based on a quantitative symbolic analysis of the Rosette Stone, Champollion realized that hieroglyphs could not just stand for words. With the help of the name cartridges for Ptolemy VIII , Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III. On the Obelisk of Philae , the Stone of the Rosette, pictures from a temple in Abu Simbel and other papyri acquired by William John Bankes , he discovered that individual hieroglyphs stood for letters, others for entire words, or that they were even context-defining.

In September 1822, Champollion succeeded in setting up a complete system for deciphering the hieroglyphs. On September 27, 1822, the Frenchman presented some of his research on hieroglyphics to the members of the Academy of Inscriptions and Fine Literature in Paris. But no sooner had the speaker finished speaking that day than most of the listening scientists attacked him. They accused him of plagiarism or simply questioned his translations. He published parts of the work in October 1822 ( letter to M. Dacier, the permanent secretary of the venerable institute, regarding the alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphs ) and a detailed explanation in April 1824 ( summary of the system of hieroglyphs in ancient Egypt ). Today posterity celebrates the so-called "Letter to Monsieur Dacier" as a milestone in the development of Egyptology .

to travel

In search of further Egyptian writings, Champollion spent the period from June 1824 to March 1826 in Italy, especially in Turin. There he found and translated the " Royal Papyrus Turin " - a very detailed listing of the Egyptian pharaoh dynasties. He kept this translation a secret for a while because it called into question the chronology of the Church as a whole.

From August 1828 to December 1829 Champollion led a Franco-Tuscan expedition to Egypt along the Nile to Wadi Halfa . Many of the materials discovered are the only evidence of the temples that were often used as a quarry at the time.

On March 4, 1832, Jean-François Champollion died of a stroke at the age of only 41 . He rests in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Eponyms

In 1924 the passenger ship Champollion , 1970 the lunar crater Champollion and 1987 the asteroid (3414) Champollion were named after him.

Fonts

- Lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques employés par les Égyptiens pour inscrire sur leurs monuments les titres, les noms et les surnoms de souverains grecs et romains. Firmin Didot, Paris 1822.

- Lettres à M. le duc de Blacas d'Aulps . Firmin Didot, Paris 1824-26.

literature

(sorted chronologically)

-

Hermine Hartleben : Champollion. His life and his work. 2 volumes, Weidmann, Berlin 1906

New edition: Champollion. Sa vie et son œuvre 1790-1832. Traduction et documentation de Denise Meunier selon l'adaptation du texte allemand de Ruth Schumann Antelme. Presentation de Christiane Desroches Noblecourt. Pygmalion, Watelet / Paris 1983, ISBN 2-85704-145-4 . - Jean François Champollion: Lettres et journaux écrits pendant le voyage d'Égypte. Texts recueillis et annotés by Hermine Hartleben. Christian Bourgois, Paris 1986.

- Rudolf Majonica: The Secret of the Hieroglyphics. The adventurous decoding of the Egyptian script by Jean François Champollion. dtv junior non-fiction book, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-423-79507-7 .

- Wolfgang Helck : Small Lexicon of Egyptology. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04027-0 , p. 59 f. → Champollion, Jean François .

- Barbara S. Lesko: Champollion, Jean-François. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 192-193.

- Guy Chassagnard: Les frères Champollion - de Figeac aux hiéroglyphes. Segnat Éditions, Figeac, 2001, ISBN 2-901082-12-2 .

- Lesley Adkins, Roy Adkins: The Code of the Pharaohs. The dramatic race to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2002, ISBN 3-7857-2043-2 .

- Monique de Bradké: Champollion et ses amis les pharaons. Ed. SdÉ., Paris 2004, ISBN 2-7480-1405-7 .

- Markus Messling: Champollion's hieroglyphs, philology and appropriation of the world . Kadmos, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86599-161-4 .

- Andrew Robinson: How the Hieroglyphic Code Was Cracked: The Revolutionary Life of Jean-François Champollion . WBG, Darmstadt 2014, ISBN 3-8053-4762-6 .

Fiction

- Joël Polomski, Gilles Faltrept: Champollion, héritier du peuple kagoth. Association des Collectionneurs de Figeac, 1990, ISBN 2-9502652-1-9 (comic).

- Christian Jacq : The long way to Egypt. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek 1998, ISBN 3-499-22227-2 .

- Michael Klonovsky : The Ramses Code. Novel. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-352-00575-3 .

Movie

- “The Myth of Egypt: Jean-François Champollion. Race for the Hieroglyphic Code ” ( Memento from February 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), docu-drama , 90 min., 2 parts, production: ZDF , first broadcast: August 27, 2006 and September 3, 2006

Web links

- Literature by and about Jean-François Champollion in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Jean-François Champollion in the German Digital Library

- Grammaire égyptienne de Champollion en ligne (Edition 1836)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e ZDF : "Solving the riddle of the creation of the world" ( Memento from July 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), August 27, 2

- ↑ Berthold Seewald, welt.de of September 25, 2012, A 31-year-old decodes the hieroglyphs

- ↑ Champollion (moon crater) in the Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature of the IAU (WGPSN) / USGS

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 12458

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Champollion, Jean-François |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French linguist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 23, 1790 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Figeac in the Lot department |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 4, 1832 |

| Place of death | Paris |