Abu Simbel temples

| Nubian monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| Great Temple of Abu Simbel |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (i) (iii) (vi) |

| Surface: | 374.48 ha |

| Reference No .: | 88 |

| UNESCO region : | Arabic states |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1979 ( session 3 ) |

The temples of Abu Simbel are two rock temples on the west bank of Lake Nasser . They are located in the Egyptian part of Nubia on the southeastern edge of the place Abu Simbel and were in the 13th century BC. Built under King ( Pharaoh ) Ramses II from the 19th dynasty of the ancient Egyptian New Kingdom .

The rock temples of Abu Simbel, the great temple to the glory of Ramses II. And the small Hathor Temple in memory of Nefertari , the Great Royal Wife , stand on the 1979 World Heritage List of UNESCO . Both temples are no longer in their original location. In order to save them from the rising waters of Lake Nasser, the reservoir of the Nile that was dammed up by the Aswan Dam , they were removed from 1963 to 1968 and rebuilt 64 meters higher on the Abu Simbel plateau. There they rise today on an island in Lake Nasser, which is connected on the northwest side by a navigable dam to the town of Abu Simbel.

The name Abu Simbel is a European conversion of the Arabic Abu Sunbul , a derivation from the ancient place name Ipsambul . During the time of the New Kingdom kings, the region where the temples were built was believed to be called Meha . However, a secure assignment has not yet been made.

In today's Sudan , about 20 kilometers southwest of Abu Simbel and a little north of the second Nile cataract , the place Ibschek was in the New Kingdom with a temple of Hathor of Ibschek , who was also venerated in the Small Temple of Abu Simbel. This area is flooded by Lake Nubia today .

location

Location in Egypt |

Abu Simbel is located in southern Egypt in the Aswan Governorate , not far from the border with Sudan. The Sudanese border in the southwest at the so-called Wadi Halfa Salient is only about 20 kilometers away. Abu Simbel is connected to the governorate capital Aswan, 240 kilometers to the northeast, by a road that runs west of Lake Nasser through the Libyan desert . It is mainly used by tourist buses that take visitors to the two temples of Abu Simbel. Lake Nasser is navigable, so the temple area can also be approached from the lake side. Some cruise ships only use the lake above the Aswan High Dam. Through the Airport Abu Simbel the place also by air is achievable.

In the past, Abu Simbel was on the west bank of the Nile between the first and second cataracts . Cataracts are rapids structured by blocks or rock bars ; they were difficult to pass for navigation on the Nile, especially at low tide . Today the two mentioned cataracts near Aswan and the 65 kilometers southeast of Wadi Halfa in Sudan have sunk into Lake Nasser, which on the Egyptian side is named after Gamal Abdel Nasser , the former Egyptian president from 1954 to 1970. At the time of Ramses II, the southern border of the Pharaonic Empire was near the second cataract. The construction of the temple complexes of Abu Simbel there was intended to demonstrate the power and eternal superiority of Egypt over tributary Nubia.

History of Research and Temple Relocation

Discovery of the temples

In 1813 the Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784-1817), alias Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah , explored the area south of Kasr Ibrîm in Nubia. On the way back he learned from the locals about a particularly beautiful temple on the banks of the Nile near Ebsambal , as the place is later called in Burckhardt's notes. Then he reached the Hathor Temple of the Nefertari of Abu Simbel on March 22, 1813. While exploring the area, Burckhardt also found the Great Temple of Ramses II, which was largely covered by a sand dune . The interior of the temple was inaccessible to him due to the accumulated sand.

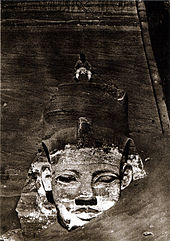

Burckhardt noted in his diary about the arrival at the Great Temple: “My gaze fell on the still visible part of four colossal statues ... They were in a deep hollow carved into the hill; It is a pity that they were almost completely buried by the sand that the wind at this point lets tumble down from the mountain like the water of a torrent. The head and part of the chest and arms of a statue still protrude from the sand. The neighboring one is almost invisible because the head is missing and the body is covered in sand up to over the shoulder. Only the headdress protrudes from the other two. "

After his return to Cairo , Burckhardt described the temples he had discovered to the Italian adventurer Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778–1823), and he also introduced him to the British Consul General Henry Salt . On behalf of Salt, Belzoni traveled to Nubia in 1817 and visited Abu Simbel. On August 1, 1817, he freed the upper part of the entrance to the Great Temple from the sand and penetrated inside. Belzoni wrote of the temple: “Our first impression was that it was obviously quite a large structure; our astonishment increased when we discovered that it was an extraordinarily rich sanctuary, adorned with bas-reliefs, paintings and colossal statues of great beauty. "

The scientific investigation of the temples began in 1828 by a Franco-Tuscan expedition under Jean-François Champollion and Ippolito Rosellini , who created a documentation of the state of the temple. Further expeditions to Abu Simbel were led by Robert Hay in 1830 and by Karl Richard Lepsius in 1844 . Robert Hay was the first to use technical measures to protect the large temple from being constantly filled with sand. As the temples of Abu Simbel became known in Europe, many travelers to Egypt visited the rock sanctuaries on the Nile as early as the 19th century. Some immortalized themselves by carving their names on the temple facades. At the end of the century, the sand on the seated colossal statues of Ramses II was more and more removed. But it wasn't until 1909 that the facade of the Great Temple was completely exposed from the sand.

Relocation of the two temples

In the 1950s, the planned construction of the Aswan High Dam threatened the accessibility and architectural integrity of the two temples of Ramesses II in Abu Simbel. In addition to the temples of Philae , Kalabsha and others, they would have been flooded by the planned Lake Nasser. As early as 1955, an international documentation center was founded with the aim of recording the area from Aswan to beyond the border of Sudan. On March 8, 1960, UNESCO asked for international help to save the temple complex. Among the numerous proposals and plans to save the structures, a Swedish project received approval in June 1963; it provided for the dismantling of the temple, the removal of the entire rock mass and the reconstruction at a higher location.

The relocation of the two temples at Abu Simbel finally took place between November 1963 and September 1968 as a worldwide joint project. The work was carried out by Egyptian, German, French, Italian and Swedish construction companies. Hochtief , headed the consortium under the planning of Walter Jurecka . The plan for the sawing of the temple came from the Swedes. At the inauguration of the dam on January 15, 1971, the then Egyptian President Anwar as-Sadat praised the relocation of the 23 Nubian temples and shrines: "Peoples can work miracles when they work together for a good cause."

For the removal and the reconstruction, 17,000 holes were first drilled in the rock in order to solidify the rock with 33 tons of epoxy resin . In addition, iron clamps were used for stabilization. Then the Abu Simbel temples were cut into 1036 blocks using a wire saw , each of which weighed between 7 and 30 tons. The cuts of the individual blocks are externally visible today. Your new location should be about 180 meters northwest and 64 meters above the level of the old temple area, whereby special emphasis was placed on the exact original orientation (alignment) of the temple. The first block was loaded on May 12, 1965 with the number GA 1A01. In addition to the temple blocks, 1112 pieces of rock from the immediate area were added to the original replica of the temple view at the new location. The completion of the relocation of the temple complex was celebrated on September 22, 1968 with a solemn ceremony.

The interior of the temple - partially suspended - is held by reinforced concrete domes above, that of the Great Temple measures 140 meters. So these are no longer real cave temples. The dome is hidden from the outside by heaped sand, rubble and original rocks (including the original facade), which preserves the original impression of a rock temple. For the time, this represented a structural achievement that is occasionally compared with the building of the temple by Ramses II. The temple relocation cost was approximately $ 80 million, donated by over 50 countries. Abu Simbel was one of the occasions for the adoption of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention of 1972 and for the creation of the UNESCO World Heritage List .

The temple buildings

| Abu Simbel temple in hieroglyphics | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pr-Rˁ-msj-sw-mrj-Jmn House of Ramses , loved by Amun |

||||||||||||||||||

Meha Mḥ3 mountain of Meha (with determinative here for hill / mountain ) |

||||||||||||||||||

| Current locations of both temples | ||||||||||||||||||

As a “ branch of the royal palace”, the temples took over the representation as “divine abode”, in which the king symbolically invokes the deities through his divine legitimation as earthly ruler in order to get in contact with them. The temples function as a link between heaven and earth within the framework of the divine celestial cosmology .

Exact data on the planning and construction of the temples of Abu Simbel do not exist, but it can be assumed that the work was carried out at the time of the Nubian viceroy Iunj: An inscription that was found near the small temple indicates that the king had entrusted one of his closest confidants to oversee the initial work. In general, the years between 1260 and 1250 BC are valid. BC as the presumed time of the temple construction. During this period the death of the great royal wife Nefertari Meritenmut falls around 1255 BC. Who played a prominent role at the court of from 1279 to 1213 BC. Reigning king Ramses II played. It is mentioned for the last time in the 24th year of Ramses II's reign on the occasion of the inauguration of the two temples of Abu Simbel.

The colored reliefs inside the temples give clues to the time of origin . In the large temple, for example, campaigns by Ramses, also from the time as co-regent of his father Sethos I , are depicted, which could be dated from other sources. Further clues for the time of the construction of the temple complex can be found in the way in which individual people are represented or set up. The third-born son of Ramses II, Prince Ramses , son of the second great royal wife Isisnofret , who died before the 26th year of the king's reign, is immortalized three times in the great temple without the symbol of death typical of the ancient Egyptians , which indicates a dating of Beginning of interior decoration before 1253 BC Can close.

The daughter of Ramses II and Isisnofrets Bintanat was initially given the simple title "King's Daughter" on her sculpture at the foot of the southern colossal statue of the seated king on the outer facade of the great temple, but appears on the lower band of the relief in the large pillared hall, also called pronaos , even as a great royal consort, a title she had given her even before her mother's death in 1246 BC. Received. The interior of the Great Temple should have been completed in the 34th year of Ramses II's reign, as the so-called “wedding stele” commemorating the wedding of the king with the Hittite princess Maathorneferure was no longer located inside the temple, but on the rock face at End of the south facade was erected.

The two temples of Abu Simbel were built like traditional Egyptian rock tombs and underground quarries, they were completely cut into the rock massif. Dieter Arnold describes them as "masterpieces of rock building art, which in their meaning can only be compared with the Indian rock temples of Ellora ". The Hathor temple of the Nefertari is about half the size of the main temple of Ramses II, which was driven into the rock formation to a depth of 63 meters (measured from the front edge of the foundation). The builders of the King's Great Temple were "a multitude of workers who were captured by his sword" under the supervision of the chief sculptor Piai, according to an inscription inside the temple.

Great temple

Building description and mythological connections

The architectural elements of the great temple of Abu Simbel are the translation of an Egyptian temple of the holy of holies into a rock. Here the mountain flank serves as a gate system ( pylon ), in which the architect was able to dispense with the flank towers. The temple facade is modeled on such a flank tower. Inside the temple, several halls decorated with writings and wall reliefs are lined up one behind the other up to the sanctuary. In this the images of the gods worshiped in the temple are placed. The great temple of Ramses is dedicated to the " empire triad " of the 18th to 20th dynasties, the gods Ptah of Memphis , Amun-Re of Thebes and Re-Harachte of Heliopolis and Ramses.

In addition, in the relief depictions of the temple interior, Horus was worshiped by Meha (also Harmachis ), the god Horus in his subform Harachte also found worship through the merging with Re to Re-Harachte. Horus and Re-Harachte have the falcon-headed face in common, the difference was the representation of Re-Harachte with the sun disk and the Uraeus serpent . In part, Re-Harachte of Heliopolis was considered to be of the same nature as the god Horus, for example in Upper Egyptian Behdet ( Edfu ). The Horus cult in Meha goes to this god by King Sesostris III. consecrated four places in Nubia, which in addition to Meha also included Baki ( Quban ), Mi'am ( Aniba ) and Buhen ( Wadi Halfa ). The royal consecration of Horus in the time of the 12th dynasty was supposed to serve the integration of lower Nubia into Egypt.

The adoration of Horus of Meha only played a secondary role in the choice of location for Ramses II with regard to the great temple of Abu Simbel, since Horus of Meha was a local god. Rather, the temples of Abu Simbel should be symbols of power as an expression of the ancient Egyptian philosophy of king, which send clear signals to regions near the border. Ramses II wanted to emphasize his rank as a “personified son of gods” as well as his divine legitimation on earth. This mythological relationship was also manifested in the Pharaoh's name of Horus .

There are references to the appearance of Ramses II as Horus of Meha in the relief representations of the great temple. The falcon-headed god with a human ear and ram's horn on the first southern pillar of the large pillar hall, above the depiction of Hathor von Ibschek, Horus' wife, carries the full first name of Ramses User-maat-Re-setep-en-Re , Ramses makes gifts himself. On the west wall of a side room of this hall, the Ramesisumeriamun ( proper name of Ramses) with a falcon's head, referred to as the “Great God”, takes the place of the missing Horus of Meha. Next to him, the scenes displayed there are dedicated to the gods Amun-Re of Thebes, Re-Harachte of Heliopolis, Horus of Buhen, Horus of Mi'am and Horus of Baki.

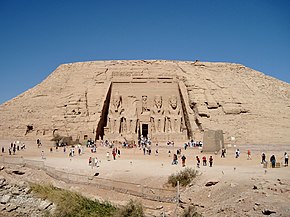

The great temple of Abu Simbel served in particular the new understanding of the royal philosophy of Ramses, who wanted to be seen in his capacity as a divinely legitimized ruler on an equal footing with other deities. This can already be seen in the four colossal statues of Ramses with the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt ( Pschent ), about 21 meters high, shown above , whose seat images “guard” the entrance to the Great Temple. The distance between the ears of each figure alone is more than four meters, the lip line is more than one meter long. The two northern seat images bear the inscription: "Ramses, the lover of Amun " and "Ramses, the lover of Atum ", the southern statues "Ramses, sun of the rulers" and "Ramses, ruler of the two countries".

The king figure south of the temple entrance is incomplete, parts of the head and torso lie on the ground in front of the facade. It was damaged by an earthquake shortly after the temple complex was built in the 34th year of Ramses II's reign. The colossal statues of the pharaoh form the main eye-catcher of the 38 meter wide and 32 meter high facade structure. The seat images are set up in pairs on the right and left of the temple entrance on a terrace. A nine-step staircase leads in the middle to their level, from where the gate to the temple can be passed through.

Above the temple facade is a frieze of 16, at least partially preserved, of the former 21 crouching, approximately 2.5 meter high baboons , the so-called sun monkeys or sacred monkeys. It was this frieze that, when the temple was rediscovered in 1813, made the Swiss Jean Louis Burckhardt aware of the otherwise completely silted up Great Temple. The baboon frieze, pictured above this paragraph in a photo taken in 2009, is the first part of the temple to be illuminated by the rising sun. Under the frieze, placed on the convex cornice of the facade, a groove with uraeus snakes and characters adorns the upper outer edge of the temple. The snake frieze served to symbolically protect the building. An inscription in hieroglyphics was attached as a dedication directly under the uraeus snakes as part of the actual temple facade .

Re-Harachte, the sun god of Heliopolis, emerges from a frontal niche above the temple entrance in the middle of the facade. It is provided with the attributes of the sun disk of Re, holding the Wsr symbol in the right hand, a head and stylized neck of an animal meaning "user" - "strong, mighty", and the Maat figure in the left for the Egyptian representation of the world order. These symbols can be read as the throne name of Ramses' II: "User-Maat-Re" - "Strong / mighty is the Maat of Re", whereby the king becomes an incarnation of Re, the "Great Soul of Re-Harachte", becomes. The representation of Re with the falcon's head also symbolizes the " Red Horus " or " Horus in the horizon " (Harmachis), a personification of the sunrise , which corresponds to the eastern orientation of the temple entrance. The figure of God is flanked on both sides by bas-reliefs, in which Ramses II offers a picture of the goddess Maat to Re-Harachte.

At the feet of the four seated colossal statues of Ramses II at the entrance to the Great Temple, smaller statues depicting members of the king's family are set up. On the side and between his legs are the sculptures of his Great Royal Wife Nefertari, his mother and wife of Seti I. Tuja , who as co-regent of Ramses II bore the title of Mut -Tuja, and some of the king's children. Among them are the princes Ramses and Amunherchepeschef as well as the princesses Bintanat, Nebettaui and Meritamun . A fourth princess pictured is nameless. All statues are elevated on the throne pedestals of the four seated images of Ramses above the terrace level. The bases are provided with reliefs of Nubian and Asian prisoners on the front and on the sides.

The temple complex, which leads 63 meters into the rock from the foundation edge on the facade to the Holy of Holies, the rearmost chamber with the statues of the gods, begins with the large three-aisled pillar hall or pronaos . Two times four statue pillars with reliefs divide the 18 meter long and 16.7 meter wide room into three areas. The statues placed in front of the ten meter high pillars form a trellis in the central aisle into the next hall. They show Ramses II, shown with the attributes and the posture of Osiris, on the right with the ancient Egyptian double crown , on the left with the crown of Upper Egypt. However, the inscriptions speak against equating the Pharaoh with Osiris, they place the king in a very complex relationship to the three deities Amun, Atum and Re-Harachte (after R. Gundlach).

The central nave of the large pillar hall with the statues of the kings is about twice as wide as the two aisles behind the four pillars, which are connected by architraves . On the ceiling of the central nave is a painting with crowned vultures of the goddess Nechbet spreading their wings , holding feathers around the king's cartouche in their claws. On the north wall there is a 17 meter long and 9 meter high relief about the battle of Kadesch in 1274 BC. Against the Hittites , in which neither side could force a decision, but it was glorified as a victory. The text, written in hieroglyphics, comes from the court poet Pentaur (pntAwr.t) . Even if the victorious representation did not correspond to the actual events, it still gives an insight into the fighting style of the Egyptians at that time. After further minor disputes, Ramses II closed in 1259 BC. A peace treaty with the Hittite empire .

In the hall, scenes from the battles against Libya , Kusch and Retjenu , which the king defeated, can also be seen. The decorations in the hall glorify the warlike deeds of Ramses II as the victor. In the rear area of the large hall one can get from the side aisles on both sides through four door openings into a total of eight side chambers, two of which were antechambers, which were probably used to store supplies or utensils for the cult activities in the temple.

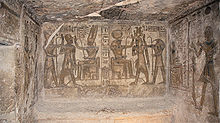

On the temple axis, behind the large pillar hall, through an originally double-winged door, one reaches the smaller four-pillar hall with pillars arranged in pairs on both sides of the main corridor, which, like the eight pillars of the great hall, divide the space into three areas under architraves. The pillars are decorated with representations of the reception and embrace of the Pharaoh by the gods, a symbol of community and favor. On the walls of the hall there are liturgical scenes: sacrificial and worship rituals as well as the procession of the holy boat , the sun boat . Another doorway leads to the transverse vestibule of the sanctuary . From there you can see into the holy of holies, the sancta sanctorum , on the back wall of which the life-size statues of Ptah, Amun-Re, Ramses II and Re-Harachte are lined up sitting on a low stone bench from left to right. The pharaoh is here on an equal footing with the triad of gods.

It is noticeable that the quality of the relief processing, in terms of technology and accuracy, gradually decreases towards the rear of the temple. Additional retaining walls also prove that the Great Temple was damaged by an earthquake while Ramses II was still alive. It may have been the same quake that caused the colossal statue of the Pharaoh to collapse south of the temple entrance.

In front of the temple there are two small chapels to the south and north, of which the north is uncovered and represents a solar sanctuary . In the center there is an altar with four sun-worshiping baboons, flanked by two obelisks . The northern chapel may represent a birthplace .

- Wall reliefs inside the Great Temple

The Pharaoh at the Battle of Kadesh

Adoration scene of Re-Harachte

Offering to Amun-Re

The sun miracle in the Holy of Holies

Abu Simbel's “sun miracle” is an event that takes place twice a year. During a certain period of time, the rays of the sun penetrating through the temple entrance illuminate three of the four statues of gods depicted in a seated position of the shrine deep in the temple: the Amun-Re of Thebes, the deified Ramses and the Re-Harachte of Heliopolis. The statue of Ptah of Memphis on the far left, an earth god associated with the realm of the dead, remains out of sunlight with the exception of his left shoulder.

After the completion of the temple complex, this always happened during the reign of Ramses II in the fourth month of the seasons Peret (February 21) and Achet (October 21). The difference in the length of a mean solar year compared to the calendar year is responsible for the fact that the azimuth of the sun position shifts every year. In addition, the leap day inserted every four years influences the date of the “sun miracle”. This results in a fluctuation range of one day in both directions. For this reason, sometimes different information about the day of the miracle of the sun is published in the literature and in publications . Assumptions that the relocation of the temple was the cause of the changing days can be ruled out from an astronomical point of view.

Since the sun miracle always occurs around the days of October 21st and February 21st, the often given statements that it takes place on the equinoxes in March and September are not correct. The equinoxes between March 19 and 21 and on September 22 or 23 mark the astronomical beginning of spring and autumn. They are the same all over the world and just as little shift as the calendar equinoxes, so that the sun miracle has no connection with it.

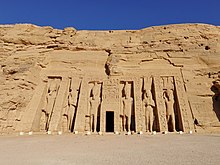

Small temple

The so-called small temple is located about 150 meters northeast of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel; it is dedicated to the goddess Hathor von Ibschek and Nefertari . In Egyptian mythology, Hathor was the wife of Horus and main goddess of the ancient Egyptian town of Ibschek near the temple complex. The appearance of Ramses II with regard to his royal office corresponded in the great temple to the falcon-headed Horus. In a similar theological orientation, he had the smaller temple built for his great royal wife Nefertari, who here represents the goddess Hathor as the king's wife. A column inscription inside the temple reads: "Ramses, strong in truth, darling of Amun, created this heavenly abode for his beloved royal consort Nefertari."

The facade of the small temple is also sunk into the rock. The figures carved out of the rock face upright and standing at ground level, each left leg slightly forward, show Ramses II and his wife Nefertari as Hathor. The six statues are separated from each other by pillars with deeply carved hieroglyphs and are all the same size, over ten meters high. This represented a special distinction for Nefertari, as the wives of the kings were usually shown smaller than them, as was the case with the great temple of Abu Simbel. Here, the children of the royal couple stand in reduced size next to the statues of their parents, the princes Amunherchepeschef , Paraherwenemef , Merire and Meriatum as well as the princesses Meritamun and Henuttaui .

The two figures of the queen carry the sun disk with two large feathers between the horns of the "cow goddess" Hathor on their heads, each holding a sistrum , an instrument dedicated to Hathor, in their left hand . They are each flanked by the four differently depicted king statues. On the left side of the facade, the two statues of the king bear the crown of Upper Egypt, the statue to the right of the entrance is decorated with the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and the head of the Ramses statue on the right side of the facade is covered with a headdress with ram's horns, which is supported by a sun disk two large ostrich feathers are surmounted. This is the Henu crown , also known as the “ostrich feather crown ” or “Henu crown of the morning house” ( Egyptian : henu en per-duat aa cheperu ). It was, among other things, an insignia worn at coronations and possibly a symbol of the royal rebirth. The images of the king are shown with the typical Egyptian apron and the ceremonial beard .

The small temple leads 21 meters into the rock formation, built like the large temple with the sanctuary at the end, but with a simpler floor plan. The gate to the temple is crowned by a bas-relief under a Uraeus serpent frieze. The cartouches with the name Ramses II are located above the snake frieze. In the entrance area there are reliefs on both sides, on the left hand with a homage by the king to the goddess Hathor by offering a gift, on the right with an adoration scene of Isis by Nefertari. You then enter a three-aisled hall, the three areas of which are separated by three pillars each connected with architraves along the central aisle. Towards the central nave, the pillars are provided with stylized heads of the face of the goddess Hathor. Among them, incidents from the lives of Nefertari and Ramses are described in hieroglyphics.

The six-pillar hall of the small temple, also called the pronaos as the first room of the temple, is mainly decorated with scenes of a religious nature. Various deities from Egyptian mythology are depicted on the sides of the Hathor pillars . The walls of the hall show the ritual killings of Libyan and Nubian enemies by Ramses II in the face of the gods Re and Amun, accompanied by the Nefertari standing behind him with a Hathor headdress. In other scenes the king offers gifts to different deities.

From the six-pillar hall you can reach the transverse vestibule of the sanctuary through three door openings, corresponding to the division of the hall with the Hathor pillars into three areas. There is an unadorned room on its north and south side. In the middle of the room, on the main axis of the temple, another doorway opens the way into the holy of holies of the small temple of Abu Simbel. In a niche slightly to the right of the back wall, the goddess Hathor is depicted in the form of a sacred cow between two pillars. Nefertari is addressed here as the appearance of the goddess Hathor, which is comparable with the representations of Hatshepsut in her temple in Deir el-Bahari . The reliefs show coronation scenes and the protection of the queen by goddesses of love and fertility.

See also

literature

(sorted chronologically)

- Johannes Dümichen : The rock temple of Abu Simbel and its sculptures and inscriptions . Gustav Hempel, Berlin 1869.

- Hans Bonnet : Abu Simbel . In: ders., Reallexikon der Egyptischen Religiousgeschichte. de Gruyter, Berlin 1952 (= reprint Nikol, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-937872-08-6 ), p. 1 f.

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt , Georg Gerster : The world will save Abu Simbel. Koska, Vienna a. a. 1968.

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt, Charles Kuentz: Le petit temple d'Abou-Simbel. "Nefertari pour qui se lève le dieu-soleil". Volume I: Étude archéologique et épigraphique. Essai d'interprétation. Volume II: Planches. Le Caire 1968.

- Hans J. Martini: Geological problems in saving the rock temples of Abu Simbel . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1970, (= lecture series of the Lower Saxony state government for the promotion of scientific research in Lower Saxony. No. 42, ISSN 0549-1703 ).

- Eberhard Otto : Abu Simbel. In: Wolfgang Helck (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie (LÄ). Volume I, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1975, ISBN 3-447-01670-1 , Sp. 25-27.

- Giovanna Magi: Aswan. Philae, Abu Simbel . German edition, Bonechi, Florenz 1992, ISBN 978-88-7009-240-0 , (Original edition: Aswan, File, Abu Simbel . Bonechi, Florenz 1992, ISBN 88-7009-238-0 ; last: 2000).

- Piotr O. Scholz: Abu Simbel. Idea of rule immortalized in stone (= DuMont pocket books. Non-European art and culture 303). DuMont, Cologne 1994, ISBN 3-7701-2434-0 .

- Dieter Arnold : The temples of Egypt. Apartments of gods - architectural monuments - places of worship . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1996, ISBN 3-86047-215-1 , p.?.

- Dieter Arnold: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture . Artemis & Winkler, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-7608-1099-3 , pp. 10-11.

- Lisa A. Heidorn: Abu Simbel. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 87-90.

- Zahi Hawass : The Mysteries of Abu Simbel. Ramesses II and the Temples of the Rising Sun . The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo 2001, ISBN 977-424-623-3 .

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt: Le Secret des temples de la Nubie. Stock-Pernoud, Paris 2002. (especially Chapters XIII-XVII)

- Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples . (Translated by Susanne Tauch) White Star Publishers, Vercelli 2004, ISBN 88-540-0070-1 , (Original edition: Abu Simbel. Asuan ei templi nubiani . Ibid, 2004, ISBN 88-540-0011-6 ).

- Rüdiger Heimlich: Abu Simbel. Race on the Nile . Horlemann, Bad Honnef 2006, ISBN 3-89502-216-0 .

- Joachim Willeitner : Abu Simbel. The rock temples of Ramses II. From the time of the pharaohs until today . (= Zabern's illustrated books on archeology ). von Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4226-1 .

- Joachim Willeitner: Abu Simbel and the temples of Lake Nasser. The archaeological guide . von Zabern, Mainz / Darmstadt 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4457-9 .

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Abu Simbel - a temple in Nubia sachmet.ch

- Abu Simbel - illustrated brief description ( Memento from January 27, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Virtual tour

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Noelle Watson: International Dictionary of Historic Places, Volume 4 - Middle East and Africa. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers 1996, p.16 , ISBN 1-884964-03-6 .

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800–950 BC). von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , p. 1110.

- ↑ a b c Dieter Arnold: The temples of Egypt. Augsburg 1996, p. 78.

- ↑ a b c Valeria Manferto de Fabianis, Fabio Bourbon (ed.): Archäologica - The Encyclopedia of Submerged Cultures. Translated from the English by Sabine Bartsch, White Star Publishers, Vercelli 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0568-4 , p. 200.

- ↑ Wolfram Giese: The rock temples of Abu Simbel , estimator of the world / heritage of humanity, data & facts

- ^ Johann Ludwig Burckhardt: Travels in Nubia . Weimar 1820, p. 132-140 ( online [accessed March 30, 2013]).

- ↑ a b Winfried Maaß, Nicolaus Neumann, Hans Oberländer, Jörn Voss, Anne Benthues: 100 Wonders of the World - The greatest treasures of mankind in 5 continents. Naumann & Göbel, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-625-10556-X , p. 194.

- ^ Giovanna Magi: Aswan. Philae, Abu Simbel. Florence 1992, p. 71.

- ↑ Abu Simbel - a temple in Nubia sachmet.ch

- ↑ Valeria Manferto de Fabianis, Fabio Bourbon (ed.): Archäologica - The Encyclopedia of Submerged Cultures. Vercelli 2004, p. 202,

- ↑ a b Giovanna Magi: Aswan. Philae, Abu Simbel. Florence 1992, p. 93.

- ↑ Irene Meichsner: Rescue from the floods, 50 years ago Hochtief was supposed to move Egyptian rock temples , Deutschlandfunk, November 17, 2013

- ^ Zahi A. Hawass: The mysteries of Abu Simbel: Ramesses II and the Temples of the Rising Sun

- ↑ a b Thomas Veser, Jürgen Lotz, Reinhard Strüber, Christine Baur, Sabine Kurz: Treasures of humanity - cultural monuments and natural paradises under the protection of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Bechtermünz 2000, ISBN 3-8289-0757-1 , p. 22.

- ↑ UNESCO : Abu Simbel - Adress delivered at the ceremony to mark the completion of the operations for saving the two temples , September 22, 1968

- ↑ Regine Schulz, Hourig Sourouzian: The temples - royal gods and divine kings. In: Regine Schulz, Matthias Seidel, Manfred Allié: Egypt - The World of Pharaohs. Könemann, Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-8950-8541-3 , p. 213

- ^ The World Heritage Convention whc.unesco.org, see section Brief History .

- ↑ Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German (2800-950 BC): the language of the pharaohs (= cultural history of the ancient world - vol. 64). von Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , p. 1143.

- ↑ Rolf Gundlach: "Horus in the Palace" - legitimation, shape and mode of operation of the political center in pharaonic Egypt . In: Werner Paravicini: The housing of power: The space of domination in an intercultural comparison of antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the early modern period. (= Communications from the Residences Commission of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Special issue 7). Christian Albrechts University, Kiel 2005, pp. 15–26.

- ↑ Thomas GH James: Ramses II. - The great Pharaoh. Müller, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-8989-3037-8 , p. 177.

- ^ Heike C. Schmidt, Joachim Willeitner: Nefertari, Gemahlin Ramses' II. , Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-1529-5 , pp. 48-49.

- ↑ Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 94.

- ↑ a b c Giovanna Magi: Aswan. Philae, Abu Simbel. Casa Editrice Bonechi, Florence 2008, ISBN 978-88-7009-240-0 , p. 81.

- ↑ Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 85.

- ↑ a b Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 100.

- ↑ Elke Blumenthal: The divinity of the Pharaoh: sacrality of rule and legitimization of rule in ancient Egypt . In: Franz-Reiner Erkens: The sacrality of rule: Legitimacy of rule in the change of times and spaces . Akademie, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003660-5 , p. 58.

- ↑ a b Giovanna Magi: Aswan. Philae, Abu Simbel. Florence 1992, p. 79.

- ↑ Valeria Manferto de Fabianis, Fabio Bourbon (ed.): Archäologica - The Encyclopedia of Submerged Cultures. Vercelli 2004, p. 201.

- ↑ Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 63.

- ↑ a b c Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. From the Italian by Susanne Tauch, White Star Publishers, Vercelli 2004, p. 67, ISBN 88-540-0070-1

- ↑ Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 70.

- ↑ a b Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 74.

- ↑ Eberhard Otto : Abu Simbel . In: Wolfgang Helck (Ed.): Lexicon of Egyptology . tape I . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1975, ISBN 3-447-01670-1 , p. 25-27 .

- ↑ Astronomical calculations with the conversion program Ephemeris Tool 4.5 according to Jean Meeus: Astronomical Algorithms ; Leipzig, Berlin, Heidelberg: Barth, 1994 2 ; ISBN 3-335-00400-0 .

- ↑ The azimuth of the sunrise does not show any significant differences in the Abu Simbel region . See also the astronomical calculations with the conversion program Ephemeris Tool 4.5 according to Jean Meeus: Astronomical Algorithms. Barth, Leipzig / Berlin / Heidelberg 1994. 2 ; ISBN 3-335-00400-0 .

- ↑ Manfred Bauer: Postponement of the "Sun Miracle" of Abu Simbel by relocating the temples. Attempt at rectification. (PDF file 99.71 kB) www.cjkchristina.de, accessed on May 28, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 88.

- ↑ a b c Marco Zecchi: Abu Simbel, Aswan and the Nubian Temples. Vercelli 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Giovanna Magi: Aswan. Philae, Abu Simbel. Florence 1992, p. 90.

Coordinates: 22 ° 20 ′ 13 ″ N , 31 ° 37 ′ 32 ″ E