Libyan desert

Coordinates: 24 ° N , 26 ° E

The Libyan Desert , Arabic الصحراء الليبية, DMG aṣ-ṣaḥrāʾ al-lībiya (the spelling of proper names mostly follows the international English transcription of Egyptian-Arabic), is a desert in Libya , Egypt and Sudan . In Egypt it is also called the "Western Desert" because of the historical animosity against Libyans and Libya, although since ancient times, including in Mesopotamia , all areas west of the Nile have been called Libya and their inhabitants Libyans (according to ancient Egyptian sources the Libyan area extends even one and a half thousand kilometers to the south, that is to about the height of the 3rd cataract , about 20th degree of latitude).

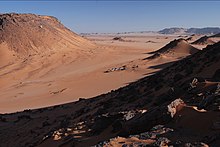

As a geographical unit, it stretches from western Egypt to eastern Libya and northern Sudan and, depending on your perspective, to the northeastern regions of Chad. All three peoples living on their territory and on their fringes (Egyptians, Libyans and Sudanese) have, however, in the course of their history a very different relationship to this once habitable savannah , but today mostly completely barren, even extremely hostile landscape of sand , Scree and rock deserts, highlands, mountains and vast plains.

The Libyan desert is one of the driest deserts on earth, but it is not only a highly complex and constantly changing natural area, but also an ancient cultural area that was and is particularly characterized by its close connection to the respective natural spatial situation.

A large cloud of Sahara sand (white band) moves across the northern half of the Libyan desert towards the eastern Mediterranean. In the center of the picture, west of the Nile, you can see the wide arch of the great oasis chain between Bahariya and Kharga. Lower left the area around the Libyan Kufra (darker spots).

Cultural and natural area Libyan Desert

The Libyan Desert is the culturally and historically most important part of the Sahara , although it only covers about 17% of its area (1.5 to 9 million km²). While other regions of the Sahara were only of importance because of their caravan routes between the highlands and their water points, the Libyan desert developed between 3500 and 3000 BC. The first advanced civilization in human history, ancient Egypt . The later empire of Kush , which was followed by the empire of Meroe , and the so far hardly explored culture of the Garamanten in Libya, with which the Berber Tuareg culture is associated there, are signs of a culturally preferred development in the area of the Libyans Desert took place. The Libyan Desert, along with the Fertile Crescent and Asia Minor , the Mesopotamia , the Indus Valley and the Yangtze River Valley as well as the Yucatán Peninsula with the Central Mexican highlands are among the most important prehistoric cultural development zones in the world.

The numerous rock engravings and rock carvings of the Libyan desert, reaching back to the pre-lithic times of the hunters and gatherers, show that where today there is an inhumane wasteland, people have lived and expressed themselves culturally for a long time. They also show a development that was a prerequisite for the emergence of the later Northeast African high cultures. Because in the southeastern part of the Libyan desert, in addition to the approximately simultaneous Lower Egyptian high culture in the Fayyum and near Merimde , the probably oldest and next to the Egyptian only Neolithic culture in Africa emerged, the Sahara-Sudan-Neolithic . This sub-sububian Neolithic of Sudan with the eastern center around Khartoum reached far into the South Sahara in the 5th and 6th millennium BC, where it is also known as Ténérén in the central Sahara and probably its origin in the highlands of the Sahara or at its edges Has. Certain ceramic shapes and types of tools are its main characteristics. Its bearers were possibly, as the rock painting period of the so-called "Round Heads" suggests, of the more black African type, but in the Epipalaeolithic the more European -looking Proto- Berbers immigrated over the Afro-Asian land bridge and are considered to be the bearers of the last Paleolithic cultures in North Africa, the Capsia and Ibéromaurus , but this question has not yet been clearly clarified. While this Neolithic did not develop any further in the western and central Sahara and existed relatively unchanged for five to six thousand years, massive environmental changes occurred in the Neolithic centers of the Eastern Sahara, which on the one hand made the desert more and more uninhabitable, and hitherto rather inhospitable The swampy Nile valley, on the other hand, turned into a privileged place of refuge, to a completely different development, at the end of which were the ancient cultures of Egypt and Nubia.

The emergence and development of the Egyptian Nile Valley culture is hardly understandable without the influences and constraints coming from the Libyan desert. Egypt was a gift from the Nile , thought Herodotus (Books of History, 2nd book, v. 1), although he actually only meant the Nile delta - but Egypt is also a gift from the Libyan desert, which makes the Nile valley like a deadly one Wall shielded it from the west and, as James H. Breasted stated in the introduction in his great history of Egypt , had such a strong spiritual influence on the inhabitants of his fertile valley, but above all ensured that they were under the climatic pressure of the increasingly drier Libyan desert in the late Neolithic could build their state in peace. Later, apart from individual predatory incursions by Libyan nomads, who, however, also ruled Egypt in the 22nd Dynasty with the Bubastids from 945 to 712, this was only threatened from the south, i.e. Nubia and from the north, i.e. from the sea, and later also from East through other ancient empires there (Persians, Hittites, Mesopotamia, Hellenes); but above all from within.

The Sahara and in particular the Libyan Desert, with the tool finds on its surface and the images on its rock walls, is evidence of human prehistory back to the time of the ancient Paleolithic Homo erectus two million years ago, and even much further back to the time of the ancestors of the great apes , whose fossils are particularly found in the Fayyum . It also shows us through many phenomena the geological, climatological and biological past of the earth itself, far behind the Tethys Sea over two hundred million years ago, because paleontologists definitely found drilling in the Libyan desert (for oil and water) the otherwise very rare marine fossils from the Cambrian period (570–505 million B.P.). The subsequent geological ages also offer partly rich findings.

Geography and topography

Naming, mapping and exploration

Apart from the historically conditioned Egyptian-Libyan controversy and the ancient aspects that accompanied it, the Libyan Desert was long viewed by conservative British geographers in particular as a unit to be viewed separately from the Sahara, despite the fact that it has such extremely different landforms as the White and Black desert, which encompasses the Mandara lakes lying like blue jewels in the Rebiana sand lake or the gigantic Wau-El-Namus crater on the extreme western edge, not to mention the inhumane, winding wadis - one in Gilf el-Kebir - Plateau is even called Winkelwadi - furrowed high plateaus with their grimly eroded precipices.

This “separatist” view was probably due to the fact that earlier in the colonial era France had the largest proportion of colonies in western North Africa and the central Sahara (only Egypt and Sudan were British, Libya was Italian, some parts like the Moroccan north coast and Western Sahara were Spanish). So there was a political stipulation to take this fact into account by using separate geographical names and thus underline the British claim to at least this eastern part of North Africa. What characterizes the Libyan desert above all as a separate unit is its extreme, globally unique aridity.

In the past, the Sahara was mostly crossed by caravan traders, locals and pilgrims; the most famous among them was the most important Arab traveler of the Middle Ages Ibn Battuta (late 11th century - 1138). The first European to explore the Sahara was the German Gerhard Rohlfs in 1865 . It was not until 1924 that Ahmed Hassanein, with a camel caravan, succeeded in drawing the first accurate maps on an expedition over 3500 km, in which he discovered the Uwainat mountain range and the springs at his foot.

From the late 1920s to the early 1940s, Patrik A. Clayton was head of the British Desert Survey in Cairo; But it was above all he who had the Libyan desert measured and the precise maps that are still used today, for example by the Egyptian army. Many of the current geographical names such as Peter and Paul for two distinctive peaks, Clayton Cairn, Clayton Craters, etc. come from him. The Hungarian Count Ladislaus Almásy also took part in one of these expeditions , who discovered the rock art of Wadi Sora, which was actually a Wadi Sura (Arabic: navel wadi) because it had this shape because of the numerous abrises and that is why it was quickly renamed in Wadi Sora (Valley of Images).

When the Germans invaded the Libyan desert from Tunisia, however, these civilian expeditions were over, and the era of the military Long Range Desert Group began, of which Erwin Rommel once admiringly said that it had done more damage than any other group of its size. Ralph Alger Bagnold had already toured the Libyan desert on private expeditions; Later in World War II as the founder and first commander of the Long Range Desert Group operating behind the lines, consisting of British, Australian and New Zealanders, he greatly expanded his knowledge of the area. On numerous trips in the 1920s and 1930s, he had also developed the techniques that are still in use today and later perfected by Samir Lama, which are required to cross desert areas with cars off- road, a knowledge without which not only modern expeditions and geological excursions, for example for oil prospecting, but also desert tourism or the rallies common today such as the Pharaoh Rally or the Dakar Rally would be impossible, not to mention the military aspects.

The country

Geographical position and extent

In North Africa, the Libyan Desert marks the eastern edge of the Sahara , the largest desert in Africa, on a square of around 1000 by 1000 km . It covers large areas of the Eastern Sahara and extends from the north south of the vegetation belt of the Mediterranean coast from the 30th parallel to northern Sudan . The local border forms at the height of the 18th parallel approximately the lower reaches of the south-west-north-east running, about 400 km long Wadi Howar , a now dried up, once very long left tributary of the Nile and today's habitat of the Kababish nomads. In the east, the Libyan desert is bounded by the Nile valley , although geologically speaking the eastern limit of the Libyan desert coincides more with the oasis arc of the Bahariya-Farafra-Dakhla-Kharga Depression, so that the 30th degree of longitude can be seen as the approximate eastern limit. The mountain ranges and parts of the desert up to the Red Sea to the east of it, but above all to the east of the Nile , which plate tectonically already belong to the folding zone that formed at the edge of the African plate and the Arab plate when they were demolished, now known as the Rift Valley or Gregory -Cheap almost all of Eastern Africa, the Red Sea and parts of Palestine, are called the Eastern Desert , in Sudan the Nubian Desert and geologically no longer belong to the depressions and plateaus of the Libyan Desert.

In the West, different authors draw the line very differently and often very arbitrarily. The reason is the fact that an originally historically ethnic term that described the habitat of the old Libyans must be defined according to modern geographical and other scientific criteria, which of course can only be achieved to a limited extent, whereby the colonial-political reasons described above play a not insignificant role have played. Some authors therefore orientate themselves on the Egyptian-Libyan state border, and in some maps the area is called Western Desert on Egyptian soil and only on Libyan Libyan desert . The British Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), which operated in the area in the forties, especially during World War II, even called the western, Libyan part Kalansho Desert or Calancio Sand (corrupted from Arabic: Sarīr Kalanshiyū ar Ramlī al Kabīr), i.e. the very flat part north of the Rebiana desert, here imposing as a rubble desert, which extends into Cyrenaica .

Others try to find a boundary that is more based on natural conditions and runs further to the west, which is mostly based on the old British survey maps and, for example, the Libyan Rebiana desert up to and including the huge Wau-El-Namus crater and further south includes the eastern half of the highlands from Tibesti to the border of Chad , i.e. roughly along the 20th degree of longitude with a southwestern bulge up to the 18th degree of longitude into the Tibesti.

Political, ethnic and geographical requirements come into play again and again. The most sensible, however, is the classification based on geomorphological criteria, especially since the geological stratigraphy is completely inconsistent and partly, as above all in the highlands, due to old tectonic and more recent volcanic processes as well as different sedimentations , especially in the area of the plateaus, and sometimes very small-scale changes Surface ranges from Precambrian to Late Pleistocene and Holocene formations, so it is of little use as a criterion.

Geographically , the Libyan Desert can best be described as the sandy desert basin in the eastern Sahara, with the Nile and a large oasis chain characterized by deep depressions to the east, the Wadi Howar and the eastern Tibesti to the south. Highlands, to the west by the Rebiana Sand Sea and the completely flat desert zone adjoining it to the north to the beginning of the coastal zone of the Cyreanika, delimited in Egypt by the Kattara Depression. However, by far not all of the quartz and therefore sterile sand that fills these basins is only dust-dry earth on the surface which, with sufficient irrigation, results in fertile soil, as demonstrated by numerous irrigation projects, especially in Egypt and Libya (see below) Hydrogeology) .

topography

The floor shape is slightly wavy. Above the crystalline basin of the Sahara, the structured basins and land steps consist of sandstone and limestone layers , remnants of the ancient Tethys Sea , the forerunner of the Mediterranean Sea, which separated Europe and Africa from one another 245 to 66 million years ago and ran right through Asia and from its former existence numerous fossils of nummulites and nummulite limestone, ammonites (there is even a real valley of ammonites in the northern part of the sandy sea), mussels (often thick mussel banks), snails, sea urchins, corals and shark teeth as well as large amounts of partly salty fossil deep water announce. However, some of these fossils also come from freshwater fauna and flora, which had established themselves in the lakes and rivers there during the last green phase of the Sahara (or in those before, see below climate history ), the remains of which are now mostly only as shallow depressions, often filled with sand or wadis impress. Other fossils come from the later advances of the Mediterranean deep into the area of the later Sahara; even the earliest fossil phase is represented by the primeval stromatolites , which are much older than that. There is even a real Nummulith Plain north of the Great Sand Sea. In between, however, especially in the plateaus, there are also zones with igneous rock and old volcanic vents with basalt formations and old lavas. Bizarre weathering forms, island mountains and geological extreme zones such as the white and black desert - one is a limestone desert, the other takes its name from the mineral black rubble on the surface - are next to gravel and sandy deserts with 30 to 40 m high, sometimes like Characteristic dunes solidified into long dune valleys in the sand sea .

The average height of the Libyan desert is around 260 m, only in the south-western part does the land rise to an altitude of 1000 m and above, the further north you go, the flatter the terrain, which then turns from sand to gravel deserts, particularly noticeable in Libya, where when driving south you cross completely flat areas for days, only periodically accompanied by the entry pipes of the large water project and high-voltage lines. (For the geomorphological aspects see below) For the basic topographical terms see article desert .

The oases

Large Egyptian oases in the Libyan desert: they have now developed from rural settlements and small caravan centers to also economically more important places, and many of them show rich traces of ancient Egyptian culture, even traces that go deep into the Paleolithic. Later they also served the pharaohs as places of exile. The word oasis comes from ancient Egyptian and means something like "cauldron, fertile place".

- The north-western oases: Siwa (easternmost settlement of the Berbers ), Sitra (salty, uninhabited).

- The four great oases of the West Nilotic Depression : Bahariya , Farafra , Kharga , Dachla .

- In addition, there are numerous smaller, mostly uninhabited oases, which often begin with Bir (source) (e.g. Bir Sahara, Bir Saf Saf, Bir Tarfawi) or indicate the existence of a well with the preface Ain (e.g. Ain Dalla) , whereby the oases Bir Saf Saf, Bir El Sarb and Bir Tarfawi, which however has salt water, were actually formed around very old, now dried up lakes that were more or less filled by the rainy season and which the Stone Age hunters preferred as places to stay, how rich archaeological finds showed. Other oases have only been newly developed through successful drilling for water, such as the new Bir Sahara 60 km from the Uwainat Mountains, which no longer has anything to do with the old oasis of the same name.

- The large oasis Fayum west of Cairo is, similar to the west Nilotic depressions and the Wadi Natrun 80 km south of Alexandria , an old depression that was at times included in the delta of the Nile when it was 18 m higher than it was later Lowering of the water level again split off part of the Nile Delta, no longer to the oases of the Libyan desert. But it is still supplied with water today by the Bahr Yusuf , a branch of the Nile that the pharaohs converted into a canal.

- Libya and Sudan: In Libya there are other large oases such as the oasis group of Kufra , plus the ancient oasis town of Garama south of the Mandara lakes, which is associated with the Garamanten and Tazerbo, as well as the now uninhabited Rebiana oasis with the Mandara lakes itself. In the area of the Libyan desert in Sudan there are among others the oases El Atrun as well as Selima and Merga (Nukkheila) (uninhabited).

geomorphology

Basic structure

The structure of the Libyan desert is determined by large thresholds and plateaus , such as the Egyptian limestone plateau, the Gilf-Kebir, the Abu-Ras, Abu-Tartur and Abu-Said plateau. Another feature are the large depressions , some of which drop to sea level or below and were formed by complex erosion processes. This did not happen due to rivers that dug depressions during the wet season, which can still be seen today as steep wadis in the plateaus and sediment colors as they flow out into the plains and there as flat wadis, but relatively soon again through sediments and later sand were replenished. In the case of the Nile, the gradient between Aswan and the mouth of the Nile is only 85 m, i.e. a few centimeters per kilometer of electricity. This situation also caused the Nile Valley alluvial land to grow by 10 cm per century until the Aswan Dam was built (and the Nasser Reservoir already holds far less water than originally planned, as the Nile mud is now being deposited there, so that it is now even downstream must be fertilized artificially). Some of these depressions are so close to the water table that oases can form such as the famous Siwa oasis with its ancient Amun sanctuary and the oases of the Western Nilotic Depression (see below) . North-east of Siwa there is even one of the deepest lowlands in North Africa, the Qattara Depression . It covers an area that is slightly larger than the state of Hesse and has a maximum depth of 133 m below sea level. This is the second lowest point in Africa (after Lake Assal ). The bottom of the Qattara Depression is mostly covered by salt marshes, i.e. sebkhas . Further geomorphological depressions lie further south, especially the Kharga Dakhla Depression (see below) .

Large forms

Probably the most impressive morphological relief units are the large sand seas , which are called ergs , especially in the central and western Sahara . The Great Sand Sea in the south and west of Egypt covers an area of 114,400 km², the North Sudanese Selima Sheet, i.e. the Selima Sand Sea, which reaches almost to Wadi Howar and which was previously only used on the death route starting from Assiut (it was mainly used for the Slave trade used) of the Darb el-Arbain , the road that could be crossed in a north-south direction for 40 days, has 63,200 km², the south Qattara sand sea 10,400 km² and the Farafra sand sea 10,300 km². The over 500 km long dune range of the Abu Muharek (Ghard Abu Muharrik) covers an area of 6000 km² (it is the longest dune in the world). The highest elevation in the Libyan desert is Jebel Uwainat at 1934 m. However, as in the rest of the Sahara, sand lakes and dunes cover only about a third to a quarter of the area of the Libyan desert, the rest are highlands, gravel and scree deserts (so-called Regs or Serir and Hammadas ).

As the most important morphological formations of the Libyan desert, not only for geological, but above all for cultural-historical reasons, because in them there are numerous complexes of finds from very different Stone Age periods, but the West Nilotic oasis depressions are considered . Geologically, these are subsidence up to a hundred meters deep, caused by the weathering of soft sandstones, which were formed here in the deepest marine areas by alluvial deposits as well as limestone deposits and were located between higher and harder layers.

Sediments were an essential geological design element of this desert. Mighty mussel beds and beds with nummulite limestone can be found almost everywhere in it, and the White Desert is nothing more than a huge limestone deposit from the Cretaceous period , sometimes over a hundred meters thick, and gradually eroding sometimes into fantastic shapes .

Also at other oases, often also in smaller depressions like Bir Tarfawi, Bir Sahara, at Wadi Halfa and in Uwainat, there were already Paleolithic find complexes of the Acheuléen with numerous hand axes , some of which are over a million years old. On the Gilf Kebir Plateau, they are also much older and do not even belong to the biface type. But later tool types of the Middle and Upper Paleolithic Levallois can also be found in abundance, as well as those of the Upper Paleolithic blade technology, evidence of a long, privileged climatic situation on such plateaus, as is shown by relevant environmental findings.

In prehistoric times, when the actual Nile valley was still largely swampy during the Holocene warm phases and also ran a few kilometers further to the west, early farmers settled here, the origin of the very old chain of oasis settlements that are there today and which once served as a buffer area to the later re-invading Libyan desert nomads, where very old cultural complexes such as those of Kharga and Dakhla emerged as early as the Paleolithic Age, in addition to the groups archaeologically located on the Nile terraces .

In the Libyan desert there are also remains of old volcanic craters such as the Wau En Namus in southern Libya and the volcanic crater area south of the Gilf-Kebir plateau near Uwainat, as well as old magma plumes that are clearly visible today, some of which have not broken through to the very top (e.g. in Wadi Abdel Malik). Impact craters from meteors have also been discovered under the sand, one of which was probably responsible for the formation of silica glass . Numerous tektites can still be found today with the help of magnets.

The Libyan Desert can therefore also be described geomorphologically within the framework of the basin-threshold structure of the Sahara as the complex of north Egyptian and Nile basins lying west of the Nile, as well as of Kufra, Dakhla and Kharga basins, which are even further west of the Tibesti -Syrte-Schwelle, south of the Sudanese Selima Basin and Abyad Plateau to Wadi Howar.

Hydrogeology

Another important, namely hydrogeological, aspect in the geology of the Libyan desert (and the Sahara as a whole) are the fossil groundwater basins , of which there are about a dozen in the Sahara and whose uppermost and thus youngest horizon is called the Savornin Sea . The oldest geologically drilled water to date is up to 400 million years old, even older than the Tethys Sea. If such a deposit is drilled, as is practiced in Siwa but especially in Libya, where - an initiative of the revolutionary leader Muammar al-Gaddafi - a 1900 km long network of four meter thick pipes ( Great-Man-Made-River- Project ), the water pushes upwards under artesian pressure and can be piped and used for agricultural purposes in pipe systems (as in Libya) and canals (mostly despite evaporation losses in Egypt) or it is bottled like the water from Siwa and sold across the country. Sometimes it pushes itself up in deep-seated areas, such as depression. Oases were created where, as in Dakhla and Farafra, the mineral water, which is often highly enriched, even gushes warm (in Dakhla 40 ° C) to the surface.

According to current theories, Savornin's Sea was formed in the last, the Würm Ice Age . Today attracting over Central Europe rain-bearing depressions shifted during herein as Pluviale affecting ends interstadials about 28000 to 23000 BP south and North Africa supplied with moisture. As a result, a green savannah landscape with lakes and rivers developed there at times (as had already happened several times before), which, however, did not drain into the sea, but instead seeped away for thousands of years into the thick layers of sediment of the old depressions, where they soaked up the water like fine-pored sponges. The water itself is not in large underground caves, but is in the pores of the sandy, several thousand meters thick deep rock. Their weight once dented the earth's crust in several places, creating the basins that are up to 6000 m deep and up to 1000 km wide. As no longer belonging to the Libyan desert Syrtebecken in Nordlibyen contain these basins also oil and gas deposits, as close in front of the peninsula of Cyrenaica and on the edge of the Arabian plate in the Sinai of the Mediterranean shelf edge of the African tectonic plate runs, which according to the current theory formation favored such deposits because of the earlier increased sinking of biological material into deep sediments (the Egyptian sites are also located in this coastal area).

When the reservoirs were filled, they formed lakes on the surface without drainage, also fed by rainwater. Gradually, fauna (crocodiles, hippos, etc., but also at least 17 species of fish, mollusks, amphibians and reptiles) probably migrated from Lake Chad, perhaps also from the Nile (this is not clear, but water connections must have existed). This can be proven on the basis of rock art, but also on the basis of archaeological excavations. The last remnant of this old lake landscape is now the increasingly silting Lake Chad, which was a huge freshwater inland sea from 30,000 years ago to around 8000 to 6000 years ago, which covered a large area of the central southern Sahara and accordingly influenced the climate.

Due to the high level of consumption, hydrogeologists estimate that the deposits will be used up in about 20 to 40 years. Overall, there are massive efforts, especially in Egypt, which is exposed to strong population pressure, to use these resources more and more extensively. This is often done very ineffectively through the cultivation of rice, which is a staple food in Egypt, in the middle of the desert or through the planting of particularly water-needing plants such as foul beans, cotton (for export, the largest part of which they make up), millet , Vegetables or eucalyptus trees. Here, the deep water is partially transported in open via long channels, so that a large part evaporates on the way (see illustration) or is pumped out of Lake Nasser, for example as part of the Toshka project, and directed to the fields, which are often far away. In Wadi Rajan there is even a large, growing lake that is fed from a particularly powerful borehole and also forms a small waterfall in the middle of the desert. If this water is pumped out more and more deeply and deeply, at some point you will come across salty deep water, which, as the rest of the old Tethys, is also stored there at greater depths, as land and sea sediments overlap repeatedly and almost like a cake and each carry water with different salinity ( Fresh water is not completely salt-free like distilled water, but is defined by a salt content <0.05%, while seawater has an average of 3.5%). This is why the consumption of fossil deep water is particularly high for irrigation, as the soil has to be constantly flushed through in order to remove the salt, which is brought to the surface by the deep current, which rises rapidly due to the high level of evaporation, where it would otherwise appear as a white salt crust would be deposited (and, moreover, even eroded the foundations of many ancient Egyptian monuments). Therefore, good is Ent drainage as important as a good Be drainage. This salinated industrial water then usually flows into the sabcha of the oasis, a drainless depression in which the water evaporates and leaves the salt behind. On the other hand, this salt can also be made economically useful and extracted with the help of evaporation basins - a very old tradition and origin of the economically important salt trade across the Sahara.

The Libyan Desert ecosystem

Only those plants and animals are considered here that exist within the desert ecosystem or at least on its edge, but not those that live on rivers or in oases or that are even domesticated (see domestication in North Africa ). Occasionally you will find birds straying in the middle of the desert, for example when they were blown by storms into the waterless depths of the desert or migratory birds that got lost during the 30 to 50 hour crossing of the Sahara. The enormously annoying camel flies do not belong here either, even if they relentlessly accompany herds and caravans, even car treks, which are mobile sources of moisture for them, through the desert.

The ecosystem is mainly determined by the lack of water as well as by the extremes of temperature and, in the case of animals, by the limited opportunities for prey. Almost all animals also live in cover, be it under stones or in caves and underground structures. Distribution and occurrence of animals and plants depend primarily on the type of habitat , i.e. whether the subsoil is rocky, gravelly or sandy or whether the habitat is a wadi, where the water table is closer to the surface, so that plants, above all, are Bushes or trees can exist. The proximity of water points or the depth of the groundwater and potential vegetation, in the case of plants, the proximity to competitors who also tap water reservoirs and protection against animal damage (through hard surfaces, spines, bitter substances and poisons) play an important role.

flora

Occurrence

In the entire Sahara there are only about 1400 different plant species, which are distributed according to the principles given above. Since the Libyan desert, however, contains all desert types of the Sahara with about the same, albeit drier, climate, an occurrence of all these plants is to be expected more or less. Nevertheless, you can drive more than a hundred kilometers through the Great Sand Sea without even encountering a living plant. Remarkably, as a family of American origin and imports in the Sahara, cacti plants hardly occur apart from opuntia , and most likely Zygophyllum fabago among the succulents .

Survival techniques

The root systems of the plants are particularly pronounced because of the delicate water supply and either extend to a depth of 35 m, or they form a network of roots close to the surface, which can reach an area of up to 100 m² even with small and herbaceous plants. The plants also all have external protective systems against evaporation , such as thickened and covered with a layer of wax, small surfaces or, as with grasses, the ability to roll up the leaves. In addition, some of them have chemical defense systems against water competitors. The seeds can survive in the dry subsoil for many years until they suddenly drift after sufficient rain, and this very quickly and within a few weeks until flowering and seed ripening (so-called ephemeral ). Such mechanisms can be observed most beautifully in the Rose of Jericho , which literally hurls its seeds out even when dry, even with low humidity. It only unfolds in order to be able to scatter its seeds, which it had previously closed and protected from mice etc. Even after such rains, the desert can quickly transform itself into a flowering meadow, provided that the subsoil is sufficiently fertile and not just rocky or sandy, although sand provides an excellent reservoir of water. However, because of its instability, there are hardly any plants on dunes, at most grasses such as the ubiquitous Stipagrostis pungens , which can sometimes even cover the dunes with a green fluff after a rain. The typical plants of the desert, especially in the wadis, are the acacia ( Vachellia tortilis subsp. Raddiana ), whose typical desert variety is also called the thorn tree because of its long thorns, and the tamarisk Tamarix aphylla , which can even use salt water. Both tree species also develop forms of reduction in layers that are heavily exposed to sand drift. A typical picture on the edge of the desert or in wadis are therefore sand hills on which seemingly large bushes grow and cover them. In fact, these are not bushes, but the crowns of the trees. The rest of the plant, including a strongly receding trunk, which merges almost immediately from the crown into the root network, is stuck in the mound and is invisible, while the crown continues to grow upwards in a kind of race for survival, depending on the degree of sand or earth drift.

Another typical plant of the desert that is the size of a melon (it actually belongs to the melon species), which is the size of a melon, is the colocinth . Even donkeys disdain them because of their bitter taste and only eat them when there is nothing else and they are very hungry. The most beautiful desert plant is undoubtedly the Cistanche phelypaea or Cistanche violacea , which is reminiscent of mullein , is about half a meter high and blooms wonderfully yellow or purple. However, it can afford that, because it uses another survival mechanism, has no leafy green and parasites by tapping the roots of other plants, which is why it is very much feared as a weed in oases etc.

fauna

Environmental conditions

The high circadian temperature fluctuations caused by lack of water, extreme heat or the dryness of the desert air as well as low prey opportunities or lack of vegetable food restrict the life possibilities of animals even more than is the case with plants and exerts strong selection pressure out. In addition, the possibilities to hide and protect yourself from predators are also severely limited by the lack of plants. Accordingly, not all animal groups are found in the desert. Refuge areas are also to be expected for smaller and specialized or residual populations. (There are even still very few small crocodiles in isolated highland wadis, such as the Ennedi and Tibesti , which always carry sufficient water .) The selection pressure and the huge waterless areas that separate the populations could on the one hand contribute to the formation of species , on the other hand the environmental pressure affects them This also equalizes the phenotypic forms of the animal species, since many animal species have to adapt to the same conditions and can therefore look very similar, although they belong to different genera, even families. Such convergent lines of development can be found in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Dittrich).

Occurrence

In total there are only 588 different animal species (Germany 48,000).

Insects are by far the most species-rich group of animals, especially the black beetles , of which there are around 340 species in this ecosystem. With 60 species each, ants and jumping terrors follow; The most notorious is the migratory locust ,which is already ranked among the ten Egyptian plagues in the Bible, actually, unlike other species of fishing horror, not a real desert animal, because it lives mainly in the outskirts of deserts. Scorpions represented by 17 species, including the extremely dangerous Saharan scorpion Androctonus australis .

There are 50 species of mammals , some of which, however, such as antelope, gazelle, especially the Dorcas gazelle , which only occurs near Siwa and Sitra, and the mane sheep (the wadan), which can only be found sporadically at Gilf Kebir and Uwainat is on the verge of extinction through overhunting. Others such as lion or wild cattle have long been exterminated or, due to the increasing aridization in the late Holocene, moved south into the Sahel . The most common are rodents , especially mice such as the gerbil (Psammomys) , the gerbil and the spiny mouse . The hyrax occurs sporadically in rocky areas.

A few small desert predators there are also like the ubiquitous strip Wiesel , as are the best-known wildlife of the Libyan Desert, the Desert Fox Fennec or the sand cat . They are exclusively nocturnal. Others like jackals and striped hyenas live mainly as cultural followers near settlements.

Birds , since they are least adapted to the desert, are present with only 18 species, including birds of prey such as hawks , stranglers , eagle buzzards and Egyptian vultures , grain eaters such as the desert sparrow or the rock pigeon and insect eaters such as the very common gossip . The former are the rarest, the latter the most numerous. Omnivores like the desert raven are most likely to be favored. But there are 5 species of lark in the Saharaalone. What they have in common, however, is that they always have to find a water source within their flight distance, and grain-eaters in particular are therefore severely restricted because of the comparatively much larger amount of food they need, even if they can do without water for a certain time.

Lizards , so lizards , geckos , lizards , Agamas and skinks there are 30 kinds, snakes are with 13. The Egyptian cobra , the only North African Kobraart, graced as King signs the end of the pharaohs, thus showing the power of life and death, said they only occurs in the Nile Valley and the less arid coastal regions. Typical desert snakes, on the other hand, are the desert horned viper and the extremely fast sand snakes Psammophis schokari and Psammophis aegyptius, which are harmless to humans .

Survival mechanisms

The survival mechanisms are based on the environmental conditions. Again, water management is most important. There are methods to use the water as optimally as possible, for example by reducing evaporation, concentrating the excretions, etc. or optimizing water absorption and storing it, for example as in the blood cells in the case of the camel , here a single-humped dromedary , whose wild form has long since died out (see below) . Some animal species even manage without any water intake and only take the water they need from their food or obtain it metabolically from fat oxidation . The respective abilities determine the location of an animal species. The regulation of salt, for example through special glands, is also important.

Another problem is the adaptation to the climatic conditions, especially the temperature regulation . It occurs either through the way of life (nocturnal), through special coloring, through digging into the sand or through the shadow of stones (scorpions, snakes). The gerbil also lives like this, and of course the scarab (Ateuchus sacer) , which the Egyptians, although without a cult, used to be a symbol of life and the primordial god Chepre (the one who developed by himself ), possibly because from the dung balls that he turned (our name is hence “Pill Rollers”) new scarabs crawled out because he had laid his eggs there. The liberation and rapid reproduction of this beetle in the Nile mud after the resignation of the Nile probably led to the opinion that it arises without reproduction, which is why it was regarded as a symbol of creativity. Another, modern theory explains the existence of a “divine dung beetle”, however, with the fact that scarabs supposedly sense the flood of the Nile early on. The animals migrated away from the water, appeared in the houses and thus announced the longed-for flooding of the Nile to the Egyptians. The regulation of transpiration is also a mechanism here, as is body structure, for example long legs and thus distance from the hot ground and the largest possible body surface ( Bergmann's rule ). Cold-blooded animals change their environment depending on their temperature, but their body temperature must never exceed 48 ° C (e.g. lizards). Another ability in the desert that can be vital for small animals in particular is to protect yourself from the wind and to be able to dig in as quickly as possible if necessary, for example in a sandstorm. The breeding and rearing of the offspring are also adapted accordingly for desert animals due to the climate.

The third factor in survival is lack of food. Here summer sleep, hiking, stock management and biologically "planned" periods of hunger offer opportunities. Cannibalism also occurs.

Some desert animals are in Egyptian mythology represented as "gods symbols" such as today only to Aswan and south of sporadically occurring golden jackal (the god Anubis ), the Egyptian vulture (the vulture goddess Nekhbet ), the scarab , the long eradicated in the Libyan Desert Lion ( Sachmet ), the wild cat or the already domesticated form (goddess Bastet ), the only sporadic falcon (god Horus and Month ), ram ( Khnum ) and the cobra ( god-king symbol ), which is more native to humid areas .

Climate and settlement history

Both factors are closely related, as the climatic fluctuations have had a decisive influence on the population of the Sahara, both positively and negatively. This is true not only, but above all, for the Libyan desert as the driest part of the Sahara, but also by far the most important in terms of population and cultural history, as it is the only place in North Africa with the long Nile valley and the wide delta including Fayum There was a retreat zone when the climate in the desert ensured the survival of the people there with their herds and smaller plantings less and less, but the coasts were too far away and already occupied (or flooded by the rising sea level), which until now was more likely The swampy, unhealthy Nile valley, which was only useful for hunting, was not considered to be so, which, in addition, was only really settable due to the increasing drought in the last third of the Holocene.

Present climate

In terms of climatic geography, the Libyan desert is one of the driest, i.e. hyper- arid regions on earth and, like the Sahara as a whole, is part of the belt of the so-called trade winds or tropic deserts, which stretch around the globe in these latitudes. The particular drought of the Sahara is based on some additional factors, some of which have not yet been fully clarified - above all the size of the North African land block and aerosols - primarily on air mass dynamic processes. The continental and therefore very dry north-east trade winds ( Harmattan ), which blows constantly, especially in winter, transports the warm, dry air that descends again over North Africa, which loses the last remnants of its moisture, back towards the equator near the ground, after it was previously in the constant equatorial High pressure area had been heated and rose to the top. This air flow also absorbs the remaining moisture from the soil and thus has an additional drying effect. The alignment of the large rows of dunes, for example in the Sand Sea, is also based on this northeast-southwest air flow. The East Saharan inland basins around Kufra, Murzuk and Kharga sometimes receive no precipitation at all for 20-25 years, on average 0.3-1.9 mm per year. In the Kufra oasis, the driest inhabited place in Africa, only 0.1 mm of precipitation falls per year. Along with the Atacama Desert, these regions are among the regions with the lowest rainfall in the world. The total annual mean of precipitation in the Libyan desert is between 0 and 5 mm (with peaks of 100 mm in the highlands). In addition, the precipitation occurs very isolated and this often only in the form of short, violent thunderstorms, which, however, can quickly turn wadis into raging rivers, even far away from the actual precipitation area, so that the most common way of death in the Libyan desert is rumored not to die of thirst , but rather drowning (which is why you should never camp on the ground in narrow wadis, but rather elevated on the edge). Numerous fulgurites in the sand, often meter-long and up to arm-thick, bear witness to the thunderstorms, which can also run dry during sandstorms .

Current population

Today, in the extremely sparsely populated area of the Libyan desert, mainly Arab Bedouins live , who in Egypt are increasingly dark-skinned towards the south and more and more similar to the Nubians of Northern Sudan, while in the coastal area and delta they sometimes even assume a Levantine character. There are numerous Berber Tuaregs in southern Libya . Your old Libyan central place Ghat (pronounced council ) is on the extreme southwestern edge of the Libyan desert, the even more important Ghadames further north. Farther south-east in the area of the Kufra oasis are populations of the black African Tubu , who, together with Berbers and Sudanese, sometimes operate flourishing smuggling routes in the winter months (these were particularly frequent during the American trade embargo against Libya) and their towering trucks loaded with material and people met again and again.

Neolithic settlement history and climatic phases

In Africa, the Neolithic was only present in Egypt, northern Sudan and on the Mediterranean coast. The sub-Saharan people switched from the Paleolithic to the Iron Age, when it was only around 1000 BC at the earliest. BC, driven by the Bantu expansion, gradually reached sub-Saharan Africa.

Environmental conditions

Up to the end of the Ice Age there were several, ever shorter advances of cold and warm air up to the extreme Younger Dryas lasting from 12,900–11,500 B.P. , and these all had an impact on the climate and humidity of the Sahara. Decisive for the settlement of the Libyan desert, however, were the Holocene climatic phases as well as the climatic periods immediately before, which with their strong aridization had initially led to the fact that people withdrew to more humid areas, i.e. the coasts, the oases and the Nile valley. When the sea then rose again after the end of this drought during the Holocene heat interval that was now beginning, a food crisis occurred among the hunter-gatherer populations, which in Europe is briefly summarized with the term Mesolithic and which is primarily associated with regional overhunting in the Middle East and in eastern North Africa finally forced a change in diet, which then ushered in the Neolithic Age. It is significant that outside of Europe there was a Mesolithic (called Epipalaeolithic in North Africa and Western Asia ) only in North Africa, and especially in the eastern part, but not in the other parts of the continent. And only here a Neolithic developed. (All now following time indications as usual from the Neolithic as BC, no longer B.P.)

The Neolithic way of life is attested not only by the rock art, but also by numerous types of tools that can be found to this day. The mortars and stones are particularly impressive. But sickles, arrow shaft straighteners , occasionally even elaborately manufactured tools with stone grinding and bores, pottery shards, etc. are abundant and show that today's desert area once offered a thoroughly livable environment, which in some cases was stable for millennia, but undoubtedly also created crisis situations during its change , which drove both the development of Neolithic techniques and the emergence of the Nile state of Egypt from the amalgamation of several regional cultural complexes and finally Upper and Lower Egypt, which is said to have been achieved by Pharaoh Narmer . The rock art is a reflection of this development. The following briefly described climatic phases of the ending Pleistocene and Holocene were decisive for this .

Late Pistocene and Holocene climatic phases of the Sahara

From 14,000 onwards, the Sahara slowly became more humid again after a prolonged dry phase caused by an advance of the European Würm / Vistula Ice Age of around 8,000-10,000 years, and the warm, humid tropical belt gradually shifted north again. This development intensified after the end of the Ice Age phase from 10,500 onwards, as this led to increased precipitation, but initially did not reach the northern Sahara beyond the 22nd parallel (today's border between Egypt and Sudan). This is evidenced by rock art from this region, in which up to 6000 the hunter and then overlapping the so-called round head period of the rock art of the Sahara predominated with depictions of numerous wild animals such as crocodiles, hippos, elephants, antelopes, gazelles, giraffes, rhinos, buffalo , Big cats etc.

7000 to 5500 the northern Sahara was dry, the southern Sahara humid. The Lake Chad had been about 20,000 years ago expanded to an inland sea the size of the Caspian Sea with appropriately strong by the evaporation effects on the Sahara (cooler and wetter), the mirror of the Mediterranean rose from 8000 to 5000 by about 40 m to ( 13,000–8,000 BC +30 m, 8000 to approx. 7000 +20 m, 6700 to this day +20 m) and covered large, previously populated coastal areas (on average about 10 km inland).

First climatic optimum: Between 5000 and 4500. Maximum of this savannah development, which now also reached the north. Agriculture began there in the 6th millennium. The population immigrated from the south. The so-called round heads of the rock art of the 7th to 6th millennium are occasionally interpreted as black African features: 7000–6000: round head period .

6000 to 1500 follows the cattle period of the Saharan rock pictures, which roughly coincides with the Sahara-Sudan-Neolithic (7th – 3rd millennium) evidenced by the similarities of the pottery patterns (dotted wave pottery, wave ceramics) and tool inventories . From 4000 onwards, a massive dry period set in, especially in the north, from which only smaller regional areas such as high plateaus, such as the Gilf Kebir, were spared.

From 3700 it was briefly more humid (second climate optimum). From 3400 onwards, drought set in again, but with smaller local wetlands, which only disappeared completely by 1300.

From around 2800 onwards, the highly arid phase of the Sahara, which continues to this day and is still advancing , began, probably triggered by the so-called “ Piora fluctuation ”, an advance of the Alpine glaciers with an aridization effect (the water was bound in ice). The desert now became completely uninhabitable and continued to expand south. Water management in the Nile Valley became necessary and triggered the formation of earlier state forms that ultimately led to the high culture of ancient Egypt. 1300 BC Finally, a climatic condition comparable to today's conditions was reached.

It is not yet completely clear how global climate change will affect the Libyan desert, but calculations have shown that, like the Sahara as a whole, it could be one of the few beneficiaries. The Sahara could become as green again as it was in the fifth millennium BC through a complex interaction, also with regard to the salinity of changing ocean currents and the resulting shifting of the West African monsoon belt to the north, as has already been the case several times in the course of African climate history .

That there can be such a change is testified not least by the changes that the Nasser Reservoir with its area of 5248 km², a length of 500 km and a width of 5–35 km has on the climate of Upper Egypt, which has been a lot wetter since then has become, which was felt above all by the local date farmers, whose fruits, which used to be particularly valued and adapted to extreme drought, no longer have the quality by far as they used to be.

Economical meaning

Apart from the water resources described, the potential for large solar energy systems and their function as an expansion area for large cities, the military, etc., the economic importance of the Libyan desert in Egypt as in Libya is rather low. This is not least due to logistical problems that arise due to its enormous extent, because 96% of Egypt and Libya are desert, and it is very expensive to build and maintain roads or railroad lines through deserts, plus temperatures that reach 60 in the summer ° C and more. Even in the vicinity of the big cities along the Nile, shifting dunes repeatedly devour entire stretches of road from the existing desert slopes, including the power and telephone lines next to them, and ordinary asphalt also does not last long in the high summer temperatures, especially when the road surface is heavily loaded Truck is constantly used and the substructure is made of sand that was simply pushed from the desert next to it.

There are some phosphate deposits as well as several deposits of iron (especially in Aswan and Bahariya), manganese, uranium, chromium and gold. Most of these deposits, however, are not located in the Libyan desert, as shown in the previous section, but in the much more mineral-rich Eastern Desert and in Sinai, as are the oil and natural gas deposits. Other deposits have not yet been exploited because of their problematic location. The oil prospecting carried out in the actual Libyan desert in the last few decades, the remains of which one occasionally comes across, were all unsuccessful.

The limestone quarries on Mokattam Hill in Cairo, from where many of the pyramid building blocks come, and the granite quarries of Aswan , whose rose granite was very popular with the pharaohs , are historically significant, even if they are not in use today . Basalt, quartzite and porphyry quarries , which supplied the coveted stones for statues as well as for the design of temples, palaces and tombs, can also be found in the Libyan desert. There were diorite deposits in Nubia, from where the pharaohs once obtained most of their gold or at least embarked from there to the gold country of Punt , from where they also obtained their incense.

literature

Titles without page numbers were used as a whole or as reference works.

- L. Almásy: Az ismeretlen szahara. Budapest, 1934 and Levegõben, homocon. Budapest, 1937. As an Unknown Sahara. New edition of the first two books in abridged form, Brockhaus, 1939.

- L. Almásy: New edition as The Swimmer in the Desert . Haymon, Innsbruck 1997, ISBN 3-423-12613-2 .

- J. Baines, J. Málek: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Egypt. Christian, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-88472-040-6 .

- P. Bertaux (Ed.): Fischer Weltgeschichte, Vol. 32: Africa. Fischer, Frankfurt 1993, ISBN 3-596-60032-4 , pp. 11-24, 35 f., 44-46.

- JH Breasted : History of Egypt. Parkland, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-89340-008-7 , pp. 13–16, 53 ff. (Reprint of the 1905 edition)

- P. Dittrich et al .: Biology of the Sahara. A guide through the fauna and flora of the Sahara ... 2nd edition. Self-published by Prof. Dr. P. Dittrich, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-9800794-0-6 .

- P. Fuchs: People of the desert. Westermann, Braunschweig 1991, ISBN 3-07-509266-5 .

- Sir Alan Gardiner : History of Ancient Egypt. An introduction. Weltbild, Augsburg 1994, ISBN 3-89350-723-X , pp. 35, 39ff. (First edition 1962)

- F. Geus: The Neolithic in Lower Nubia. In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 219-238.

- G. Göttler (Ed.): DuMont Landscape Guide: The Sahara. 4th edition DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-7701-1422-1 .

- H. Haarmann : History of the Flood. On the trail of the early civilizations. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49465-X , pp. 16f, 19f.

- W. Helck , E. Otto : Small Lexicon of Egyptology. 4th edition edit v. R. Drenkhahn. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04027-0 .

- E. Hoffmann: Lexicon of the Stone Age . CH Beck. Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-42125-3 .

- HJ Hugot, M. Bruggmann: Ten thousand years of the Sahara. Report on a Paradise Lost. Cormoran Verlag, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7658-0820-2 .

- F. Klees, R. Kuper (Eds.): New Light on the Northeast African Past. Contributions to a Symposium Cologne 1990. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-927688-06-1 .

- Barbara E. Barich: Holocene Communities of Western and Central Sahara. Pp. 185-206.

- JD Clark: The Earlier Stone Age / Lower Paleolithic in North Africa and the Sahara. Pp. 17-38.

- Angela E. Close: Holocene Occupation of the Eastern Sahara. Pp. 155-184.

- M. Kobusiewicz: Neolithic and Predynastic Development in the Egyptian Nile Valley. Pp. 210-218.

- PM Vermeersch: The Upper and Late Palaeolithic of Northern and Eastern Africa. Pp. 99-154.

- F. Wendorf, R. Schild: The Middle Palaeolithic of North Africa. A status report. Pp. 39-80.

- R. Kuper (Ed.): Research on the environmental history of the Eastern Sahara. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-927688-02-9 .

- St. Kröpelin: Investigations into the sedimentation environment of Playas in Gilf Kebir (Southwest Egypt). Pp. 183-306.

- W. Van Neer, HP Uerpmann: Palaeoecological Significance of the Holocene Faunal Remains of the BOS Mission. Pp. 307-341.

- The New Encyclopedia Britannica. 15th ed. Encyclopedia Britannica, Chicago 1993, ISBN 0-85229-571-5 .

- Th. Monod: Désert libyque. Editions Arthaud, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-7003-1023-3 .

- Th. Monod: Deserts of the World. CJ Bucher, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7658-0792-3 , pp. 33-46, 55-118, 163-172.

- Mathias Döring, Anton Nuding: Water in the Libyan desert of Egypt . Wasser & Boden 10/2002, 29-35.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ K.-H. Striedter: rock art of the Sahara. Prestel, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-7913-0634-0 .

- ^ JD Clark: The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, ISBN 0-521-22215-X , pp. 559-582.

- ↑ See Clark: The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 1, p. 571 ff.

- ↑ See Baumann: Die Völker Afrikas , Vol. 1, pp. 97-103.

-

↑ a b M. Schwarzbach: The climate of prehistory. An Introduction to Paleoclimatology. Pp. 222-226, 241-255. Ferdinand Enke Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-432-87355-7 .

HH Lamb: Climate and Cultural History. The influence of the weather on the course of history. Pp. 125-148. 3. 6. T. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-499-55478-X .

R. Schild, F. Wendorf, Angela E. Close: Northern and Eastern Africa Climate Changes Between 140 and 12 Thousand Years Ago. In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 81-98. - ^ L. Krzyzaniak: The Late Prehistory of the Upper (main) Nile. Comments on the Current State of Research. In: In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 239-248.

- ↑ W. Henke, H. Rothe: paleoanthropology , pp 82-85, 474-477. Springer, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-540-57455-7

- ↑ JSTOR.org: Lieut.-Colonel Patrick Andrew Clayton In: GW Murray: The Geographical Journal. Vol. 128, No. 2 (June 1962), Blackwell Publishing, pp. 254-255

- ↑ Uni-Köln.de: Wadi Howar: Settlement Area and Thoroughfare at the Southern Margin of the Libyan Desert Project A2

- ↑ The Kababish Tribe of Sudan ( Memento of the original from September 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. THE ANCIENT HISTORICAL SOCIETY.org

- ↑ Abu Muharek. ( Memento of the original from April 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Sahara. Water Report - The sea in secret . In: Geo Special 6/92, ISBN 3-570-01089-9 , pp. 92-103.

- ^ Precipitation in the Sahara on sciencing.com

- ↑ Katharina Neumann: Vegetation history of the Eastern Sahara in the Holocene. Charcoal from prehistoric sites. In: Kuper (Hrsg.): Research on the environmental history of the Eastern Sahara . Pp. 13-182.

- ↑ Climate Change Research Center: The Copenhagen Diagnosis 2009 - Updating the World on the Latest Climate Science (PDF 3.3 MB)