Domestication in North Africa

Animal and plant domestication in North Africa are two of the three primary hallmarks of a Neolithic culture . All others such as stone grinding and drilling, special tools such as sickles and rubbing stones , techniques such as weaving and spinning or plowing as well as the preliminary stages of writing are ultimately like the immaterial, i.e. cultural, religious and social phenomena such as division of labor , stratification and hierarchization of society, Real trade or sedentariness are partly inevitable consequences of the three primary factors. The third primary factor is the use of ceramics , which has already appeared in Africa as a phenomenon of partially settled hunters and gatherers . It became important for arable farmers to store food or to prepare it more elaborately.

Basics

In the different areas in which the Neolithic (partly in the Holocene) originated, i.e. above all the valleys of the Yangtze and Indus , the Mesopotamia and later in Central America and the Andes (where there were no animal domestications apart from the lama ), there were very different focuses, depending on which plants and animals were available. This also had consequences for basic cultural techniques. In ancient America, for example, the wheel was not used as a commodity (already invented, but only for children's toys), since especially in Mesoamerica there were no migratory or riding animals to be domesticated in nature and in the mountainous Andean region, where the llama is a suitable animal was available, wheels weren't very useful.

Important in case North Africa but the fact that the Sahara than here far the largest regional topographic and climatic unit at the time of domestication in the Holocene no desert was, but, has, among other things by finds of fishing tackle, such as fishing hooks , harpoons and fish bones, a tree savannah with Water points, lakes and rivers, possibly gallery forests , and it was only later that it changed into the extremely dry area, as it is today in the Eastern Sahara, also known as the Libyan desert . Accordingly, the flora and fauna there was composed differently and offered a different starting material for attempts at domestication. This applies to both animal and plant domestication, with the latter being expected to have savannah and oasis vegetation in today's Libyan desert, which is why species were included in the plant domestication section that today only occur in humid areas such as the Nile valley or the delta or on the Mediterranean coast, especially since when looking at ancient Egyptian frescoes you will notice how many trees and other plants are depicted here. This form of vegetation has been archaeologically documented, among other things, through the evaluation of charcoal at prehistoric sites and of pollen and plant seeds in sediments.

Pets

Problem

The Eastern Sahara is of particular interest here. The statement still to be found in specialist books up to the eighties of the last century that the only three animals domesticated in Africa are the donkey, the cat and the guinea fowl can no longer be sustained in this way today; rather, the Neolithic domestication process is now much more complex. Overall, agriculture in Egypt started relatively suddenly around 5200 BC. With the arrival of a complete bundle of domesticated plants and animals from the Near East. In general, the Merimde culture and the Fayum culture on the southern edge of the Nile Delta show very close relationships with the Levant . The skeletal finds there are more similar to those in the Middle East than to those of the local population, so that some scientists suspect that it may have been a migration from the direction of Palestine.

There are several ways to determine the origins of today's pet:

- the genetics and biology of wild and domestic animals,

- their current distribution and their races,

- archaeological findings, e.g. B. bones, mummies and implements,

- Illustrations and other representations in art as well

- occasional reports in ancient texts.

Occasionally domestications were also carried out in parallel in several parts of the world, whereby it could have happened later that domestic animal breeds were mixed through imports.

Domestications are also meaningful in terms of their composition and origin for every culture, especially with regard to economics, religious customs, but also social factors. For the Sahara and its cultures, apart from the pure coastal areas, which were mainly information corridors for cultural techniques leading from east to west, the focus here is primarily on Egypt and Northern Sudan, where it is against the background of the Sahara-Sudan Neolithic and the Lower Egyptian Neolithic gave several original and / or parallel domestications. Most of the large domestic animals in the Eastern Sahara and especially in the Nile Valley are imports or, as may be the case with cattle and donkeys, independent domestications, which were also carried out in parallel in other cultures within the framework of animal breeding, which began everywhere that today it is often hardly possible to determine exactly where the origin was. Own domestications are to be assumed above all if the wild forms occur or did occur in the area of today's Eastern Sahara, i.e. the Libyan desert.

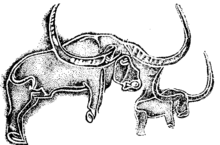

Particularly interesting in this context is the case of the cattle, which was found in the so-called Bubalus field image period between 6000 and 1500 BC. BC across the area of the Sahara when, however, semi-wild cattle were initially kept. Numerous Neolithic shackles that prevent animals from running away can still be found in the desert today. The southern limit of the occurrence of wild cattle was apparently the 25th parallel.

Small pets

Of the small domestic animals , only the chicken can be excluded with certainty as North African domestication. The current form comes from the Southeast Asian Bankiva chicken (Gallus gallus) ; the four species of fruit flies living in the Sahara are out of the question. The guinea fowl , which is widespread in Africa, is a special case here . Ancestral form is the helmeted guinea fowl (Numidia meleagris) , which is spread across Africa with around 20 subspecies. It was already known in predynastic Egypt, where it occurred much further north than it is today, and where it was probably domesticated and later adopted by the Romans, but disappeared in the Middle Ages for unclear reasons and only rediscovered by the Portuguese at the end of the 15th century and was domesticated a second time. There is even a guinea fowl hieroglyph ( sennār ).

Ducks and pigeons are problematic, but the former is iconographically significant, with the latter being the wild form in the Sahara to this day; they are therefore listed below. Hares were never domesticated worldwide (although there was a Hasengau near Hermopolis Magna and Amarna in Egypt , which probably referred to the wild hares that were common there, especially since all 7 Egyptian districts with animal names are not named after domestic animals), rabbits only in the early European Middle Ages.

With the exception of the guinea fowl already mentioned, the following domestications can be assumed to be potentially possible or certain for the area of the Libyan desert, in particular northern Sudan, eastern Libya and ancient Egypt:

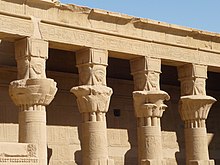

- The honeybee Apis mellifera is adjacent to the Chinese silkworm the only domesticated insect at all and was probably first domesticated in the 4th millennium following the much older and used mainly in Europe in the rock art wild bees use in Egypt, probably as a result of nests destructive overexploitation , which was previously operated and thus dramatically reduced the number of bee colonies. An early representation can be found in the temple of Ne-User-Re in Abū Ghurāb around 2400 BC. The importance of beekeeping in ancient Egypt can also be seen from the fact that the bee was used as a symbol of Lower Egyptian royalty and appears in many hieroglyphs and especially in the names of kings ( ideogram : King of Lower Egypt). But also in other ancient cultures, such as that of the Chaldeans , the bee was a ruling symbol. It is based on the image of a well-organized state led by a king (the queen bee was long thought to be male); In addition, the bee hieroglyph with six legs is the symbol of the wheel with six rays and thus the symbol of the sun . The beekeeping in clay tubes (it exists in Egypt to this day) and the processing of honey are attested several times on representations in graves.

- The gray goose Anser anser , the ancestral form of the domestic geese, was domesticated in Egypt in the 2nd half of the 3rd millennium. The oldest evidence of its domestication comes from there, and it became a popular food and sacrificial animal alongside the Egyptian goose, white-fronted goose and bean goose. They were caught with nets (see picture) and then fattened. Apparently the transition from captivity to complete domestication took place. Indicative is the ever more frequent occurrence of white geese, which are hardly viable in the wild because of the lack of camouflage, in the representations. A grave relief from the 5th Dynasty (2480–2320 BC) already shows the stuffing of geese.

- The duck as a domesticated descendant of the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) was possibly kept in Egypt and Mesopotamia, especially for the cult of the dead (but this also applies to the later non-domesticated pintail Anas acuta) . However, the stage of actual domestication does not seem to have been reached, but only, as with the goose, captivity, which in this case only became real domestication in the late Middle Ages of Europe. However , the duck is quite common as a hieroglyph , especially in the meaning of son , i.e. also in king names that often begin with son of Re etc.

- The pigeon comes from the rock pigeon (Columba livia) which is widespread worldwide and also lives in the mountainous fringes of the Sahara . Even today you can find large pigeon houses on many house roofs in Egypt, which are mostly still built in the country as it was common in ancient Egypt. The small pigeons of the genus Streptopelia that live in the desert or their peripheral areas or oases do not belong to the zoological archetypes of the domestic pigeon. Presumably, the domestication was not targeted, but rather the pigeon seems to be gradually similar, as it may have been with the dog (as a hunting companion who ate the remains) and the cat (here because of the mice and rats in the granaries) after having preferred to settle in the small rural Neolithic settlements of the early period because of the rich grain supply there as a cultural follower. In any case, there is first evidence for the 5th millennium BC. In the Syrian-northern Iraqi region and in Palestine, where the dove later became a central symbol in Judaism. Probably less economic motives were in the foreground everywhere, but religious ones , although in Alan Gardiner's list ( Gardiner list ) not a single pigeon hierarchy is listed and the word pigeon is also missing. However, pigeons were already in the 3rd millennium BC. On the menu of the Egyptians. Around 1300 BC They were also used here as couriers, for example to deliver the news of the coronation of a pharaoh. Mythologically, however, no other bird played such a prominent role as the dove, which in the Near East, India and Egypt was considered a symbol of the mother goddess, love and fertility, as well as purity.

- The house cat Felis silvestris libyca can be found as an independent domestication in Egypt in the 2nd millennium BC. BC, so only in the New Kingdom . Occasional domestications are likely to have occurred earlier, as well as later crossbreeding of other wildcat species is considered possible. As the sacred animal of the goddess Bastet , the cult of cats experienced a climax in the 22nd and 23rd dynasties (945–715 BC). Bubastis in the delta was then the city of the goddess and was under Libyan rule. Cats, like dogs, were often mummified and buried with honor.

- Possible domestication dog : dog or jackal-headed hybrid creatures, which may represent shamans, already exist in the rock art of the Sahara (hunting period in Wadi Mathendous des Fezzan and in Tadrart Acacus ). The oldest document in Egypt so far comes from the 5th millennium BC. BC (bone finds from the Neolithic settlement of Merimde-Benisalâme, western Nile delta). Since there were no wolves in North Africa, it must have been an import, possibly from the Middle East. It is likely to have been a type of greyhound that was mainly kept for hunting purposes and was later even buried, as shown by illustrations from the Old Kingdom showing the so-called Tesem , pharaoh dogs, such as those used by Tutankhamun for hunting. Very soon, as numerous representations of the Middle and New Kingdom show, there were already different breeds of dogs from small lap dogs to heavy dogs and fighting dogs suitable for lion hunting as well as palace animals with different tail, leg, ear and body shapes, similar the current situation. He describes the god Anubis as a hieroglyph . The jackal hieroglyph has the figurative meaning dignity, value. Whether the dog / jackal also served as a symbol of the god Seth is hotly debated. However, since the jackal was already connected to Anubis and the symbolic animal of Seth, like the god himself, would have to have strongly negative properties, this is considered unlikely for both the dog and the jackal (and donkey) (more likely for the aardvark , which some Egyptologists consider a symbolic animal for Seth).

Big pets

Sheep (from the wild sheep of the genus Ovis , which does not occur in North Africa), goats (from the wild goats of the genus Capra , east of the Nile only the non-domesticated ibex was native) and pigs (from the wild boar Sus scrofa ) were not domesticated in North Africa but introduced later, namely at about the same time at the beginning of the 5th millennium BC. In any case, the first archaeological evidence for all three animal species is from this time in Merimde-Benisalâme in the Nile Delta, an indication that they were imported from the direction of Palestine and / or Mesopotamia, where there were already relatively easy connections along the coast As the exchange of other Neolithic cultural techniques shows, which has been demonstrated, for example, for the early phase of the Neolithic Merimde culture with the Levant, from where stone tool forms, ceramics and above all emmer, flax and also sheep, goat and pigs were imported, as well Cattle , the domestication of which is not fully understood. Of the four animal species mentioned, only cattle and pigs were native to North Africa in their wild forms, for example the wild boar in the Nile valley and on the north-western coast, the wild cattle in the coastal area of North Africa; but they were first domesticated in the area of the fertile crescent . (For the problem of the Bubalus see below. )

Since the wild form of the goat did not exist in the Sahara, the old Neolithic form of the goat demon, which is probably the earliest supernatural entity in the Near East, is also missing. In the rock art it was apparently replaced by dog-headed animals, and it does not appear in Egyptian mythology either. It remains unclear whether the controversial dog's head of Seth, a deity similar in nature, can be associated with this, as well as whether the Egyptian gods developed from this theriocephaly of shamanism , as we encounter it in the early rock art.

Horses and camels are not independent domestications in northeastern Africa either. However, since there are rock art epochs named after them for them, they are described here because of their special cultural relevance.

It is unclear whether the donkey originated autochthonously in Egypt, where its wild form was. The domestic cattle, on the other hand, of which there was also the wild form in North Africa, has a certain, not unproblematic special position here because of its unclear relationship to the bubalus of the rock art:

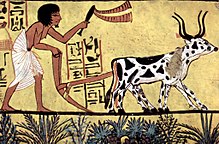

- Cattle: The Middle East is considered to be the origin of cattle breeding ( Göbekli Tepe , Çatalhöyük , etc.). The cattle reached no later than the beginning of the 5th millennium BC. BC Egypt, because cattle bones that could be dated to this time were found in Merimde-Benislâme, and it was later the most important domestic animal of ancient Egypt, first as a meat supplier, later also as a pack animal and draft animal in agriculture, but hardly as a milk supplier (presumable reason was the lactose intolerance that was very widespread in North Africa then and now ). Its cultic significance as a symbol of gods ( Hathor and Apis animal) and as a sacrificial animal was great. Its ancestry is, however, quite complex ( paraphyletic to polyphyletic ), as one has to reckon with no fewer than three to four genera, not including the never domesticated, only hunted bison , which we encounter above all in European cave paintings such as the Magdalenian . The domestic cattle species found worldwide today developed from these genera: Bos , to which wild cattle and zebu belong, Bibos ( Balirind and Mithan ), Poephagus ( yak ) and Bubalus , which is only found today as a water buffalo in South and Southeast Asia. Earlier in the late Pleistocene , the buffalo existed as a wild animal in North Africa and the Near East, for example at the time of the early advanced civilizations in Mesopotamia , where it is represented in numerous representations and has religious significance, a phenomenon that is widespread over almost the entire Mediterranean region. However, whether there was an independent center of cattle domestication in the Eastern Sahara is disputed, as is whether the rock paintings there are depictions of Bubalus or wild cattle, although the horns are typically crescent-shaped to the rear and not, as in cattle, to the front. which in many cultures made the cattle a symbol of the moon and fertility, which some illustrations seem to prove. However, many researchers tend to assume that the pasture areas of the Sahara, especially in the area of Tibesti , which is particularly rich in such rock art, were more likely to have been developed from the Nile valley, which would have been possible under the environmental conditions at the time. Such a population exchange between the then climatically by no means privileged, rather uncomfortable swampy area of the Nile Valley and the interior of the Sahara savannah certainly did exist, because such a wide spread of cultural forms over the almost five millennia-long Sahara-Sudan Neolithic almost the entire southern Sahara region would not have been possible under desert conditions. The fact that the cattle were domesticated relatively early is also shown by the fur piebald in Egyptian representations, which does not occur in wild cattle and must be the result of crossbreeding. The long-horned Bos africanus seems to have been the basis . The common cattle shape of ancient Egypt was the longhorn, familiar from rock art. Later there are indications of crossbreeding with probably introduced short horn forms in the New Kingdom. The root form was probably the long-horned wild cattle (Ur or Aurochse ) (Bos primigenius) spread across Eurasia (northern border 60th degree of latitude) and North Africa , which later had short-horned forms and especially in Africa with the much better tropicalized and hump-shaped forms ( zebus ) the subspecies Bos namadicus was crossed. The fact that all types of cattle are fertile and crossbreed with one another, but not buffalo and cattle, raises the still unresolved question of what part Bubalus really played in the domestication of cattle in North Africa, especially since the rock paintings are not necessarily due to the lack of perspective can provide conclusive evidence. The fact that the sub-Saharan buffalo is considered the most dangerous wild animal in Africa speaks against domestication. Molecular genetic investigations may be used here. Overall, a 3000 to 4000 year long southward expansion from central North Africa can be observed in cattle, which began around 5000 BC. And is evidently also to be understood in connection with the parallel climate change of the now increasingly drier Sahara, which forced the shepherds to move south with their herds or to the coast or into the Nile valley.

- Donkey: The donkey domesticated in the Middle East in the first half of the 4th millennium , of which, remarkably, there is no actual rock painting period and hardly any or no images in rock art (at that time, the cattle period of rock art prevailed, whose bearers were (semi) nomadic cattle herders that probably had no additional need for pack animals) comes from the now long extinct African wild ass Equus africanus , a distinct inhabitant of deserts and semi-deserts. It is evidenced by illustrations first in Egypt on the city palette from Abydos (end of the 4th century BC), and later also from graves of the 5th dynasty in Saqqara as a versatile pet. Whether this can be taken as evidence that it was first domesticated from the Nubian wild ass in ancient Egypt, as has been reported in many literature, is, however, again disputed according to recent West Asian findings. It was also used as a riding animal by the noble, but mainly in a pair as a litter carrier. As a real and royal mount, however, it was only seen from around the 17th to 15th centuries BC. Occupied.

- Horse: It was probably already in the 5th millennium BC. Domesticated in Central Asia, where its original form also lived. From around 1500 the horse period of the rock art begins in the Sahara , a sign that the horse is now used as a pet. The early pharaohs, especially of the Old Kingdom, however, can only be imagined on sedan chairs carried by donkeys, because the first horses were only introduced in Egypt during the time of the Hyksos (1650–1541), who the Egyptians mainly because of their horse-based war techniques defeated and subjugated, introduced as draft animals mainly for chariots, but riding always remained of subordinate importance, especially since inventions such as horseshoes , spurs and stirrups were only introduced relatively late shortly before and after the turn of the century, especially by the equestrian peoples of Central Asia ( Scythians , Avars, Huns , Mongols ) and Europe and were imported to Egypt even later, so that the riders of that time probably only had a saddlecloth and simple reins available, as they were also used with draft animals. The horse was largely unusable in the desert because of its high and constant need for water, which also points to the low need not only of the Egyptians of that time to cross the desert, which for them was primarily the place of the dead.

- Camel: Shortly before the birth of Christ begins the camel period of the now qualitatively more and more decreasing, sometimes graffiti-like rock art , which points to the introduction of the domestication of camels also in Egypt at the turn of the century , actually single-humped dromedaries whose original, long-extinct wild forms can be seen in the South of the Arabian Peninsula suspected where it may have been domesticated in Oman in the 3rd millennium BC, as it was previously in the highlands of Iran and in Mesopotamia . But it was not one of the classic domestic animals of ancient Egypt, as it cannot tolerate the humid Nile valley climate. It was not until the Ptolemaic period (305–30 BC) that it finally established itself as a domestic animal in Egypt and the Sahara, a sign of how little the Egyptians needed for animals, which the dreaded desert unscathed could traverse. And today it mainly serves as a meat supplier, as you can see from the numerous transports with meat camels that roll downhill towards Cairo. Occasionally, however, you can still find camel caravans, especially in the central Sahara, which is difficult for cars to pass.

- Attempts at domestication: They are documented in ancient Egypt in the 12th dynasty for the oryx antelope and the Dorcas gazelle , but have apparently been abandoned for unknown reasons, presumably unsuccessful, although the oryx in particular because of its suitability for the desert (it hardly needs water because it itself metabolically produced) would have been very suitable.

Plant domestications

Problem

Their origin is significantly more difficult to determine than that of domestic animals, as there are at most archaeobiological finds for them, but hardly any images from the period relevant for domestication, although ancient Egyptian frescos are teeming with plants mostly depicted as harvest products, but their species-specific assignment is often correct is speculative. And reports are usually not particularly meaningful, if available. In addition, parallel developments and mixtures that can hardly be deciphered are to be expected here. On the other hand, what was basically said about domestication of domestic animals also applies here, namely that the way in which the Neolithic approached the critical food crises that accompanied the various climate changes is significant for the state of their cultural development. And it is not for nothing that the structure of the domesticated sub-Saharan flora looks completely different from that of North Africa and here in particular that of Egypt and North Sudan, which were and were favored by the spatial proximity to the core areas of the Neolithic, for example in the Fertile Crescent and in Mesopotamia and Asia Minor not only obtained most of their pets from there, but also many of their useful plants, of which basically only potentially the date palm, certainly the papyrus, possibly the flax (flax) as well as probably sorghum and finger millet and perhaps the pea in the north-east African greater area (also) were domesticated, but not the grains. On the other hand, this indicates how close the cultural contact between Sudan, Egypt and the Middle East was from around the 5th millennium BC. BC in the late Neolithic to pre-Dynastic times of the Merimde and Fayum-A culture . The diffusion of these domestications into the Sahara-Sudan-Neolithic is a further symptom of this development. B. can also be recognized by the presence of mortars, rubstones and earlier ceramics, which were mainly associated with the storage, preparation and consumption of vegetable food.

Gardiner's hieroglyphs for plants include: palm, lotus, papyrus, reed, bulrush, sedge, emmer, corn, flax and wine.

Non-food crops

Of the non-food plants cotton , flax and papyrus , only the latter is definitely an Egyptian domestication.

- The cotton comes from India, where it was used for around 3000 BC. Was first detected in the Indus culture , but in Mexico much earlier ( Tehuacán 4300 BC). It probably came to Mesopotamia in the first millennium BC from India, with which there were already trade connections at that time. In Egypt, although uncertain sources suggest a much older use, it appears to have been introduced by the Islamic Arabs, who also brought cotton to Europe around 800 AD. The extensive cotton cultivation, which is actually unsuitable for the intensive cultivation of the Nile Valley, which is poor in land, may even have been a consequence of colonialism. The British rule in Egypt was particularly decisive here, when 92% of Egyptian exports consisted of cotton (a good half today).

- Flax ( flax fiber ) is one of the oldest fiber and food crops (the oil seeds were pressed, eaten and given to the dead as food). In Iran, 7000 to 9000 year old flax seeds and capsules of the wild flax form have been found, and in Syria hundreds of seeds of a cultivated flax form have been found. As a cultivated plant it has been in Egypt since the 5th millennium BC. Known. It was first used as a food in the 4th millennium BC. Later it was of great importance as a raw material for canvas in various qualities (the best was called royal linen ). The mummies are all wrapped in linen. The earliest evidence of flax cultivation can also be found for the 5th millennium BC. In Mesopotamia.

- Papyrus had been in use in Egypt since the 3rd millennium BC and was the most important writing material for a long time until the discovery of paper manufacture . It was also used for building Nile boats. (In 1969/70 Thor Heyerdahl therefore tried to reach Morocco from America with the papyrus boats Ra I and Ra II, which were designed according to the Egyptian-Phoenician model , in order to prove the Egyptian settlement of the continent as at least a technical and seafaring possibility.)

- The Egyptians' preference for flowers of all kinds is also striking, some of which were very sacred, such as the lotus , which they regarded as the primordial being and symbol of the primordial god Nefertem and the course of the sun. They literally poured flowers over their dead, as is known from Tutankhamun's mummy. Flower motifs are also common in frescoes, architecture and everyday objects such as fans or furniture, which create a particularly strong contrast to the desert that the Egyptians everywhere surrounding them.

However, none of the three useful plants are desert or savannah plants and are therefore of little importance here, especially since their use is already culturally relatively highly developed (writing, comfortable to luxurious clothing that can be differentiated from one position to another) and technical requirements (combing, spinning, weaving, tailoring, etc.) is a prerequisite, especially if one takes into account that the use of sheep's wool for fabric production in Egypt continued into the 2nd millennium BC. Was unknown, although sheep had been kept since the beginning of the 5th millennium.

Food crops

The best connoisseur of Egyptian history after J. H. Breasted writes about the plant-based menu of the Egyptians:

“At the best of times in its history, Egypt's resources were incomparably large. With the exception of the worst years, there was an abundance of grain. Its most important types were barley, spelled, a coarse-grained type of wheat ( spelled ). Vegetables were mainly lentils, beans, cucumbers, leeks and onions, fruit dates, sycamore figs and common figs, persea ( avocado pear ) and above all the heavenly gift of grapes. "

- None of the actual types of grain , neither emmer , einkorn , barley - these were the first domesticated types of grain - wheat , spelled or rice , of which there is an African variant, comes from North Africa. Wheat and barley, which require a Mediterranean climate, were first grown in the Middle East, from where they soon reached North Africa, where they were grown mainly with the help of irrigation systems on the Nile and later in Ethiopia, but nowhere else in Africa. The southern cultivation limit for northeast Africa was around Khartoum.

- Other domesticated grasses : In addition to sorghum and finger millet (Eleusine coracana) and pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) as the most important plants, six other grasses were domesticated in Africa. The main growing zone for sorghum was the Sahel zone , i.e. the area between Lake Chad and the Nile. The first two plants are relatively resistant to drought and could therefore have their origin in the area of today's Libyan desert when it was a little more humid. Their importance presumably results from the fact of the aridization, which they tolerated the longest. The earliest evidence for the first two plants comes from impressions on pots from Kadero (Sudan). Overall, however, other desert grasses were apparently used, as well as grasses that were only distributed south of the Sahel, such as African rice, but which are not relevant here.

- Root plants: None of these plants, not even the onion discussed in connection with vegetables, is indigenous to North Africa. This also applies to yams as the most important, which was probably not imported from Asia, but was also domesticated in southern Africa and is now mainly grown in western Africa, where it is the most important starch supplier. Although it has probably existed in Africa for four to five thousand years, it is not detectable in the north of the continent, which is also due to the fact that as a tuber it leaves no archaeologically usable traces. But neither is it documented in ancient Egypt. During the wet phases of the Sahara there could have been yams there, especially since it was certainly very popular as a nutritious and sweet-tasting tuber (raw it is poisonous) during the hunter-gatherer times.

- Tree fruits: The fig Ficus carica was domesticated very early in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia and Palestine, has been known there as a useful plant for over 11,000 years (11,400 B. P. Jericho) and was widespread throughout the Mediterranean. It was already known and sought after in the Middle Kingdom. The date palm has been proven to be a useful plant in North Africa and a plant of oases, where it is often found wild. However, their ancestry has not been established for certain. The oil palm was used for 4000 BC. Proven near Khartoum. The pomegranate tree, which is popular in Egypt , probably comes from the West Himalayas and southern Central Asia and was already around 3000 BC. Cultivated in the eastern Mediterranean region, it is one of the oldest cultivated plants. Of the tree fruits mentioned by Gardiner, the sycamore fig is a fruit of the classic desert tree sycamore as early as the Old Kingdom around 2600 BC. Occupied. However, since the fruits do not taste particularly good and were mainly administered as a medicinal product, Gardiner could also have meant the real fig, which also belongs to the mulberry family. With Persea but the native of America avocado pear can not be meant, perhaps, but a native of Asia Minor and spread throughout the Mediterranean laurel tree that's like Persea belongs to the laurel family, which occasionally (such as in the English Grand Webster ) also collectively Persea become.

- Among the vegetables and legumes , the broad bean , which is native to the Near East, should be mentioned here. Most of the beans planted today come from America. The cowpea or cowpea is native to Africa, where it is still grown today. Cultivation in West Africa dates back 5,000 to 6,000 years and was closely linked to the cultivation of sorghum and pearl millet. The pigeon pea , native to northeast Africa , was found in Egyptian tombs from the 3rd millennium and could be a local domestication. The lentil also belongs to the very old cultivated plants and was cultivated in the Orient. But here, too, it is true that there were no plants from North Africa. Of the vegetable plants cucumber , leek and onion mentioned by Gardiner, the cucumber is not known until 600 BC. Coming from India for Mesopotamia and for 200 BC. BC in the Mediterranean area, so that this is probably a confusion, probably either with the watermelon , of which the first domesticated forms from around 2000 BC. Originate from ancient Egypt and western Asia or with the sugar melon , whose domestication dates back to around 3000 BC. Is estimated and since about 2000 BC. In ancient Egypt, as well as in Mesopotamia, eastern Iran and China, in India around 1000 BC. The latter in particular is very similar in appearance and taste to the cucumber, provided that it is not sweet. The leek (Allium porrum) or garlic (Allium sativum) , a plant mainly native to Central Asia, which grows wild all over the Mediterranean region , has been around as early as 2100 BC. BC for the Sumerians and a little later also for ancient Egypt, for example as the food of the pyramid workers. The onion (Allium cepa) Finally, a leek relatives, also one of the oldest cultivated plants in the world. Its original form comes from the area of Afghanistan. Ancient Egypt knew them over 5000 years ago and saw them as a symbol of the universe because of their round shape. As in all such cases, it is impossible today to say who domesticated them first and where that happened, presumably as in other cases one has to reckon with several origins, especially since onions of all kinds, especially those of the genus Allium , are considered Easy to find, tasty and medicinal (it contains the antibacterial and antihypertensive allicin ) tubers have certainly been on the menu of the Paleolithic.

- Wine: The domestication of wine took place in the Middle East. It is certain that the Sumerians were already involved in viticulture in the 4th millennium. But viticulture was already known in Egypt around this time . One of the original forms of the grapevine also occurs as far as Palestine and Northwest Africa (Vitis vinifera ssp. Sylvestris) , the other, Vitis vinifera ssp. caucasica, comes from the Ukraine, Caucasus (probably the place where wine was first invented, as the story of Noah suggests), and is spread across Iran to Kashmir. But here, too, it is true that wine was an important cultural and ancient phenomenon, especially for the Eastern Sahara region, but does not come from there.

Literature and evidence

- Barbara E. Barich: Holocene Communities of Western and Central Sahara. In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 185-206.

- Norbert Benecke : Man and his pets. The story of a relationship that goes back thousands of years. Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8062-1105-1 .

- John Desmond Clark : The Cambridge History of Africa . Vol 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, ISBN 0-521-22215-X

- Angela E. Close: Holocene Occupation of the Eastern Sahara. In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 155-184.

- P. Dittrich et al: Biology of the Sahara. A guide through the animal and plant world of the Sahara with identification tables and 170 fig. 2nd edition. P. Dittrich, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-9800794-0-6 .

- Sir Alan Gardiner : History of Ancient Egypt. An introduction. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1994. OA 1962, ISBN 3-89350-723-X

- F. Geus: The Neolithic in Lower Nubia. In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 219-238.

- Herder Lexicon of Biology. 10 vols. Spektrum Akad. Verlag, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-86025-156-2 .

- G. Göttler (Ed.): DuMont Landscape Guide: Die Sahara , 4th edition. DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-7701-1422-1 .

- W. Helck, E. Otto: Small Lexicon of Egyptology. 4th edition edit v. R. Drenkhahn. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04027-0 .

- E. Hoffmann: Lexicon of the Stone Age . C. H. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-42125-3 .

- HJ Hugot, M. Bruggmann: Ten thousand years of the Sahara. Report on a Paradise Lost. Cormoran Verlag, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7658-0820-2 .

- F. Klees, R. Kuper (Eds.): New Light on the Northeast African Past. Contributions to a Symposium Cologne 1990. With contributions by R. Kuper, JD Clark, F. Wendorf u. R. Schild, R. Schild, F. Wendorf u. Angela E. Close, PM Vermeersch, Angela E. Close, Barbara E. Barich, M. Kobusiewics, F. Geus, L. Krzyzaniak. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-927688-06-1 .

- L. Krzyzaniak: The Late Prehistory of the Upper (main) Nile. Comments on the Current State of Research. In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 239-248.

- R. Kuper (Ed.): Research on the environmental history of the Eastern Sahara. With contributions by Katharina Neumann, St. Kröpelin, W. Van Neer and H.-P. Uerpmann. Heinrich Barth Institute, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-927688-02-9 .

- Katharina Neumann: Vegetation history of the Eastern Sahara in the Holocene. Charcoal from prehistoric sites. In: Kuper (Hrsg.): Research on the environmental history of the Eastern Sahara . Pp. 13-182.

- R. Schild, F. Wendorf, Angela E. Close: Northern and Eastern Africa Climate Changes Between 140 and 12 Thousand Years Ago. In: Klees, Kuper (Ed.): New Light on the Northeast African Past . Pp. 81-98.

- M. Schwarzbach: The climate of prehistory. An Introduction to Paleoclimatology. Pp. 222-226, 241-255. Ferdinand Enke Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-432-87355-7 .

- A. Sheratt (Ed.): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archeology. Pp. 179-184. Christian Verlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-88472-035-X

- K.-H. Striedter: rock art of the Sahara. Prestel, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-7913-0634-0

- The New Encyclopedia Britannica. 15th ed. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., Chicago 1993, ISBN 0-85229-571-5 .

- W. van Neer, HP Uerpmann: Palaeoecological Significance of the Holocene Faunal Remains of the BOS Mission . In: Kuper (Hrsg.): Research on the environmental history of the Eastern Sahara . Pp. 307-341.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. K. Neumann: Vegetation history of the Eastern Sahara in the Holocene.

- ↑ JD Clark (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Africa , Vol. 1, p. 490

- ↑ Br. Viktor Näf: Domestication of plants . ( Memento of the original from May 12, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 39 kB) Lecture, April 1, 2009, at the OF Langenthal.

- ↑ See travel guide »wikivoyage.org«

- ↑ According to the Egyptological Institute of the University of Tübingen, this hieroglyph is still missing today.

- ↑ Wadi Mathendous on the English Wikipedia

- ↑ New findings on domestication and genetics of cattle. ( Memento of the original from October 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 170kB) yakzucht.ch, July 23, 2003

- ↑ Reichholf, pp. 221–224.

- ↑ Egyptian cotton on it fits

- ↑ Archeology of Kadero: L. Krzyzaniak: New Light on the Early Food Production in the Central Sudan . In: Journal of African History XIX, 1978, pp. 159-172.