Bubastis

| Bubastis in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

Baset B3st Baset |

|||||

| Greek | Βούβαστος | ||||

Map of Egypt |

Bubastis ( ancient Egyptian Baset ; also Per-Bastet ) was an ancient Egyptian city and was located in the southern part of the eastern Lower Egyptian Nile Delta . Their remains can be seen today on the southeastern edge of the modern city of Zagazig , the capital of the Sharkiya province . The site of the ancient settlement is in Arabic as Tell Basta /تل بسطة / Tall Basṭa / 'Bastet Hill'. In the Old Testament she appears as Pi-Beseth (Ezekiel 30, 17). The term "Bubastis", which is common in Egyptology, comes from the Greek form of the city name Per-Bastet ; Bastet's house back. The city was the cult center of the goddess Bastet , who in later times was often worshiped as a cat.

Historical meaning

Due to its strategically favorable location close to important trade and traffic routes, such as the Pelusian and Tanite arm of the Nile and the Wadi Tumilat , Bubastis has held an important position among the settlements of the delta since the early dynastic period . The Bubastis region originally belonged to the 14th Lower Egyptian Gau , the so-called "Ostgau", and was transferred to the 13th Lower Egyptian Gau in the 5th Dynasty (approx. 2504 to 2347 BC). In the Ramesside period (approx. 1290 to approx. 1070 BC) the area of Bubastis formed the 18th Lower Egyptian Gau after separation.

The city finally reached the height of its importance under the kings of the 22nd dynasty (approx. 946 to 713 BC), who probably partly resided in this city and expanded the temple of the city goddess Bastet comprehensively and monumentally. Bastet was often depicted as a lion and later a cat-head. Numerous bronze figures of cats come from Bubastis. Even in the time of Herodotus , Bubastis was widely known for its great temple and the annual Bastet festivals in honor of the goddess .

"The dead cats are brought to the city of Bubastis, embalmed and buried in sacred burial chambers."

The city was still important in Greek and Roman times. A temple of Agathos Daimon is attested from this period . Structural elements in a purely Hellenistic style are also evidence of archaeoglically public buildings from this period.

archeology

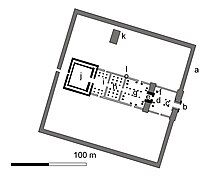

It can be assumed that Bubastis was important from an early age, because the city goddess Bastet is mentioned in several inscriptions of the 2nd dynasty. From the following Old Kingdom (around 2750 to 2150 BC) come some decorated mastabas , such as B. That of the Anchchaf from the 6th dynasty (approx. 2318 to 2150 BC), the head of the granaries and head of the priest of Pepi , the grave of the only friend and scribe of the royal documents Anchembastet and the head of the Priest ihy. These grave complexes have decorated grave chambers and show there memories, offerings and the titles and names of the grave owners. A few more mastabas come from the so-called western necropolis, which were decorated with a limestone stele on the east side. The stelae show the owner of the grave before a brief inscription and probably date to the end of the 6th Dynasty or the beginning of the First Intermediate Period. Those buried here bear the title of head of the Mautjeret and overseer of the priests . The grave of Mermerire's only friend , which contained a number of inscribed copper modeling tools, also dates from around this time . Two royal Ka temples also date from the 6th dynasty, the better preserved being built by Pepi I (around 2295–2250 BC). The complex of Pepi I has a large courtyard with a small temple, which is not in the middle of the courtyard, but rather offsets. This temple was decorated with two pillars at the entrance. This was followed by a hall decorated with eight pillars and five chapels on the back wall. A relief from the complex shows Pepi I standing in front of Bastet and Hathor behind him, as well as Iunmutef and a fertility deity. The other Ka temple belonged to Teti II. Its surrounding wall was about 112 × 56 m in size, but the actual temple is poorly preserved. Royal Ka temples of the Old Kingdom are well known from inscriptions. The temple in Bubastis is the best preserved and only secured temple of this type from the Old Kingdom and is therefore of particular importance for research. From the late Middle Kingdom (approx. 2000 to 1750 BC) comes a large palace and another necropolis in which burials of the mayors of that time were found. A relief with the name of Amenemhet III was found in the palace . and the mention of his first sed festival . Various statues were also found in the palace, including those of the mayor and head of the priest Chakaure-seneb . The mayors were apparently buried in the necropolis next to the palace. This necropolis consists of a large building with various rooms that served as burial chambers. The central burial chamber is clad with limestone. Other extensive necropolises come from the New Kingdom. There were numerous clay coffins and many simple ushabti. The family grave of the king's son of Kush , Hori III, dates from the 20th dynasty . , in which his coarse but large granite sarcophagus and numerous shabtis were found. In the western part of the field of ruins there were cat cemeteries and numerous bronze figures of cats. In the area of the Ka temple of Pepi I there are also remains of a Roman bath.

In a geomagnetic survey carried out in October 2008, another large-scale structure was discovered south of the Bastet Temple.

Bastet Temple

The center of the ancient city was the Bastet Temple. The majority of its remains come from the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period, but some components come from the Old and Middle Kingdom. Much of the temple's blocks have been found loose. So the temple is very badly damaged and it is difficult to get a precise idea of how it once looked. Stone is rare in the delta, so stone blocks have often been reused after a temple was torn down. Blocks were also often transported from one place to another. This means that not all components found in Bubastis necessarily come from buildings in Bubastis. One can only be certain if Bubastis or Bastet are also mentioned in surviving inscriptions. Remnants of the Old Kingdom may indeed have been dragged from other places to Bubastis. The names of Chufu and Chephren appear on fragments. Bastet is sometimes mentioned on parts of the Middle Kingdom, so they probably come from a temple from that time. An example is an inscription from Amenemhet I and his mother Bastet. Various rulers of the Second Intermediate Period, such as Chajan and Apopi , appear on stone fragments. Remains from the time of Amenhotep III. and with the name Ramses II. indicate construction work under these rulers, but many blocks of the latter can also come from the Ramses city, which served as a quarry in the Third Intermediate Period. From the under Amenophis III. Acting vizier Amenhotep found two statues. Most of the royal statues found in Bubastis bear the name of Ramses II. In the temple area there was also a colossal statue of a Ramessid queen who was usurped by Karoma , wife Osorkon II.

Under Osorkon I, the temple was considerably expanded. Remains of a portico come from its construction. Its gates and pillars were made of granite, the walls of limestone. The building was expanded under Osorkon II . Significant remains of a red granite gate have survived. They show representations of the Sed festival . These representations are among the most extensive sources on this festival, which Osorkon II celebrated in his 22nd year of reign, which is unusual as it usually took place in the 30th year of reign. Blocks of the gate are still on site today, but also in various collections such as in Berlin, the Louvre or the British Museum. Osorkon II also built another hypostyle hall with Hathor columns , that is, the capitals of the columns show the face of the goddess Hathor . The ruler also dedicated a red granite shrine in the temple. Osorkon II dedicated a small temple to the god Mahes , not far from the temple of Bastet.

Under Nectanebo II , the temple was expanded and the Holy of Holies was even completely redesigned. The ruler's new holy of holies was about 60 × 60 m and probably replaced that of the old temple. The walls of the new building consisted primarily of rose granite. Fragments of basalt and quartzite indicate that important components were made of this material. Remains of four types of shrines are attested. The main nausea of the Bastet was about 3.5 m high and placed in the center of the temple house. Another shrine was dedicated to the Bastet, mistress of the shrine , which was once about 3 m high. Its fragments are now in London and in the grounds of Tell Basta. According to iconographic specifics, this naos was perhaps originally a barque shrine that housed the cult barque of the goddess and / or her barque cult image. In addition, all guest deities worshiped in Bubastis had at least one other naos. They were dedicated to the Month, Horhekenu, Harsaphis, the Sekhmet, the Wadjet, and the Schesemtet. The temple is also the site of a copy of the so-called Canopus Decree . It is about the resolution of a priest synod in 238 BC. BC, the 9th year of the reign of Ptolemy III.

Treasure finds

Various treasures were found in Bubastis . On September 22, 1906, when the rails were being laid, a hoard of silver and gold vessels came to light, some of which were bought by the Metropolitan Museum in New York . The objects date to the 19th dynasty. The reigning queen calls a vessel Tausret . Another treasure came to light on October 17, 1906 in the area of the Bastet Temple, again consisting of silver and gold vessels. This find ended up in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. A third treasure find came to light on April 9, 1992, again in the area of the temple, and consists of a series of golden amulets and pieces of jewelry that were found in two alabaster vases.

See also

literature

(sorted chronologically)

- Edouard Naville : Bubastis. (1887-1889) (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Vol. 8, ISSN 0307-5109 ). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, London 1891 ( digital on-line )

- Edouard Naville: The Festival-Hall of Osorkon II. In the Great Temple of Bubastis. (1887-1889) (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Vol. 10). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, London 1892, digitally on-line .

- Kurt Sethe : Bubastis 2 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume III, 1, Stuttgart 1897, Col. 931 f.

- Labib Habachi : Tell Basta (= Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Egypte. Supplément 22, ZDB -ID 281662-3 ). Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, Cairo 1957.

- Ahmad El-Sawi: Excavations at Tell Basta. Report of Seasons 1967-1971 and Catalog of Finds. Charles University Prague, Prague 1979.

- Mohamed I. Bakr et al .: Tombs and Burial Customs at Bubastis. The Area of the so-called Western Cemetery (= Tell Basta. Vol. 1). University of Zagazig - Institute of Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Cairo 1992, ISBN 977-235-041-6 .

- Christian Tietze et al. (Ed.): Reconstruction and restoration in Tell Basta. (= Arcus. Vol. 6). Universitätsverlag Potsdam, 2003, ISBN 3-935024-71-1 .

- Hans Bonnet: Bubastis. In: Hans Bonnet: Lexicon of the Egyptian religious history. Nikol, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-937872-08-6 , p. 126.

- Neal Spencer: A Naos of Nekhthorheb from Bubastis. Religious iconography and temple building in the 30th Dynasty (= British Museum. Research publication. Vol. 156). With a contribution by Daniela Rosenow. British Museum, London 2006, ISBN 0-86159-156-9 .

- Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl, Faye Kalloniatis (eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. = ʾĀṯār misrīya (= Museums of the Nile Delta. Vol. 1). Opaion, Cairo / Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-00-033509-9 .

- Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl, Faye Kalloniatis (eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from the Eastern Nile Delta. = ʾĀṯār misrīya (= Museums of the Nile Delta. Vol. 2). Opaion, Cairo / Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-00-045318-2 .

Web links

- Provisional website of the Tell Basta Project

- Excavation finds from Bubastis at MUSEUMS IN THE NILDELTA (project MiN)

Individual evidence

- ^ Herodotus , Historien II, 60, 137-138.

- ↑ Herodotus: Histories. Translated by A. Horneffer , ed. by HW Haussig (= Kröner's pocket edition. Vol. 224). 4th edition, Kröner, Stuttgart 1971, ISBN 3-520-22404-6 , p. 129.

- ↑ Veit Vaelske: Bubastis / Tell Basta in Roman times. In: Festschrift for Günter Poethke on his 70th birthday (P. Poethke) = archive for papyrus research and related areas. Vol. 55, H. 2, 2009 ISSN 0066-6459 , pp. 487-498, doi : 10.1515 / APF.2009.487 .

- ↑ Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl: The Pharaonic Cemeteries of Bubasties. In: Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl, Faye Kalloniatis (eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Title of uncertain translation, perhaps head of the prizewinners , so: Elmar Edel : Contributions to the Egyptian Lexicon V. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde . Vol. 96, 1969, pp. 4-14, here p. 14.

- ^ Mohamed I. Bakr et al .: Tombs and Burial Customs at Bubastis. 1992, pp. 92-103.

- ↑ Ahmad El-Sawi: Excavations at Tell Basta. 1979, pp. 72-73.

- ↑ E. Lange: The Ka facility Pepis I in Bubastis in the context of royal Ka facilities of the Old Kingdom. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. Vol. 133, 2006, 121-149; Plate XXVII – XXXIII.

- ↑ Ahmad El-Sawi: Excavations at Tell Basta. 1979, pp. 75-76.

- ^ S. Farid: Preliminary Report on the Excavations of the Antiquities Department at Tell Basta (Season 1961). In: Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Vol. 58, 1964, ZDB -ID 1254744-x , pp. 85-98.

- ^ Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl: Egyptian Sculpture of the Middle Kingdom from the Palace at Bubastis. In: MI Bakr, H. Brandl, F. Kalloniatis (Eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from the Eastern Nile Delta . Cairo / Berlin 2014, pp. 6–25.

- ^ Edouard Naville: Bubastis. 1891, pp. 52-55.

- ^ Daniela Rosenow: Revealing new landscape features at Tell Baste , Egyptian Archeology 37, London 2010, pp. 17-18.

- ^ Edouard Naville: Bubastis. 1891, plate XXXIIA, B.

- ^ Edouard Naville: Bubastis. 1891, plate XXXIIIA.

- ^ Edouard Naville: Bubastis. 1891, plate XXXV, A, C.

- ^ Edouard Naville: Bubastis. 1891, plate XXXVF, E.

- ^ Theresa Steckel: A Statue of Ramesses II from Tell Basta. In: Egyptian Archeology. 38. 2011, ISSN 0962-2837 , p. 6.

- ^ Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl: Bubastis and the Temple of Bastet. In: Mohamed I. Bakr, Helmut Brandl, Faye Kalloniatis (eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. 2010, pp. 27–40, (hypothetical reconstruction of a plan on p. 33).

- ^ Dieter Arnold : Temples of the Last Pharaohs. Oxford University Press, New York et al. 1999, ISBN 0-19-512633-5 , p. 36.

- ^ Edouard Naville: The Festival Hall of Osorkon II. In the Great Temple of Bubastis (1887-1889). 1892.

- ↑ W. Barta: The Sedfest representations of Osorkon II in the temple of Bubastis. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. Vol. 6, 1978, ISSN 0340-2215 , pp. 25-42.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Temples of the Last Pharaohs. Oxford University Press, New York et al. 1999, ISBN 0-19-512633-5 , pp. 38-39.

- ^ Daniela Rosenow: The Naos of Bastet, Lady of the Shrine. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology. Vol. 94, 2008, ISSN 0307-5133 , pp. 247-266.

- ^ Daniela Rosenow: The Great Temple of Bastet at Bubastis. In: Egyptian Archeology. Vol. 32, 2008, pp. 11-13; Neal Spencer: A Naos of Nekhthoreb from Bubastis. 2006.

- ↑ Christian Tietze, Eva R. Lange, Klaus Hallof : A new copy of the Canopus Decree from Bubastis. In: Archives for Papyrus Research and Related Areas. Vol. 51, 2005, pp. 1-29.

- ^ MI Bakr, H. Brandl: Precious Metal Horads from Bubastis. In: MI Bakr, H. Brandl, F. Kalloniatis (Eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. 2010, pp. 43-44.

- ^ MI Bakr, H. Brandl: Precious Metal Hoards from Bubastis. In: MI Bakr, H. Brandl, F. Kalloniatis (Eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. 2010, pp. 44-45.

- ^ MI Bakr, H. Brandl: Precious Metal Hoards from Bubastis. In: MI Bakr, H. Brandl, Faye Kalloniatis (Eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. 2010, pp. 45-47.

Coordinates: 30 ° 34 ' N , 31 ° 31' E