Graecization

The Gräzisierung is the assimilation stranger in the Greek language and culture and the Greek rendering of foreign names in European culture.

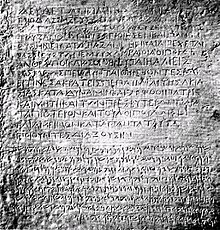

Antiquity and late antiquity

The assimilation of other ethnic groups has been going on since classical antiquity , when Greek culture and language spread in the eastern Mediterranean with Hellenism , at the time of Alexander the Great in India, and later. The Graecization of the Eastern Roman Empire was largely complete by the 7th century .

Due to the linguistic relationship in Greek, Latin names were and are always given with the Greek ending and declined. Thus Caesar to Καῖσαρ Kaisar , Augustus to Αὔγουστος Augoustos , Maecenas to Μαικήνας Maikēnas or Octavius to Ὀκτάβιος Oktábios - as reversed by Latinization were received Greek names into Latin: Ὅμηρος Homer became Homer , Σωκράτης Socrates to Socrates .

Numerous names of historical personalities are familiar in their Greek form - mostly because they have been passed down by Greek authors, for example:

- from Egyptian: ' Cheops ' (from Χέοψ Chéops for King Chufu); ' Mykerinos ' (from Μυκερῖνος Mykerīnos for Menkaure)

- from Persian: Xerxes I. and Xerxes II. (from Ξέρξης Xérxēs for Hšayāŗšā)

- from Arabic (non-classical): Maimonides (for Musa ibn Maimun); Algorithmos (mostly Latinized algorithm ) according to Al-Chwarizmi (similar sound to logarithmos; this word is also usually used in the Latinized form logarithm ).

With the Hellenization of the Middle East, proper names and toponyms were also Graecized. In Palestine, Graecization prevailed above all in the upper class, which was also the main bearer of the Greek language and culture for a long time elsewhere. Examples of this are the given names 'Maria' ( Μαρ Marα María for Marjam or Mirjam) or 'Elisabeth' (for Elischeba).

humanism

In the epoch of humanism it was popular among scholars and aristocrats to translate names into Greek, sometimes with the Latin ending -us instead of Greek -os . Some of them have established themselves as family names.

The historical background was the final collapse of the Byzantine Empire in the 15th century. Greek-speaking scholars emigrated in large numbers to Central Europe, where their influence resulted in increased interest in ancient Greek authors. In addition to Latin , ancient Greek also established itself as the language of scholars.

Examples of Greek family names

The word component "-ander" is always on ἀνήρ (anḗr) [Gen. ἄνδρος (ándros)] 'man' with the root word ἀνδρ- (andr-) .

- Aepinus for "high" (from αἰπύς aipýs 'high')

- Auleander for "Hofmann" and "Hoffmann" (from αὐλή aulē 'Hof' and -ander)

- Chytraeus for "(cooking) pot" (for example for David Chyträus ; from χύτρα chýtra 'pot')

- Dryander for "Eichmann" (from δρῦς drỹs 'Eiche' and -ander)

- Erythropel for "Rothstatt" (from ἐρυθρός erythrós 'red' and πόλις pólis 'city')

- Macrander for "Langemann" (for example for Arnoldus Langemann ; from μακρός makrós 'big' and -ander)

- Micrander for "Kleinmann" (for example for Georg Adolf Freiherr von Micrander; from μικρός mikrós 'small' and -ander)

- Neander for "Neumann" (from νέος néos 'new' and -ander)

- Oinotomus for "Schneidewin" (from οἶνος oĩnos 'wine' and τομός tomós 'cutting')

- Oryzius for "Reissner", "Reisner", "Reusner" (from ὄρυζα óryza 'Reis')

- Tectander for "carpenter" (from τέκτων téktōn , carpenter 'and -ander)

- Tragus for "Bock" (for example for Hieronymus Bock ; from τράγος trágos 'Bock')

- Xenopol for "Calmasul" (Romanian noble family from Câmpulung Moldovenesc in Bukovina; from ξένος xénos 'foreign' and πόλις pólis 'city')

Personalities

- Capnio for Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522) (from καπνός kapnós 'smoke')

- Thomas Gephyrander Salicetus for "Brückmann" (from γέφυρα géphyra 'Brücke' and -ander)

- Ioannes Gerobulus (probably Johann Outraad or Johann Oldrate, Frisian theologian; from γεραιός geraiós 'old' and βουλή boulē 'advice, advice')

- Philipp Melanchthon for "Schwarzerdt" (from μέλας melas , black 'and χθών chton , Earth')

- Andreas Osiander for "Hosemann" (controversial, see Osiander )

- Ambrosius Pelargus (from πελαργός pelargós 'stork')

- Johannes Poliander for "Graumann" (from πολιός poliós 'gray' and -ander)

- Nickname Protucius, Greek for “Vor-Meißler” (from πρό pró 'before' and τύκος týkos 'chisel'), from Conrad Celtis

Modern

For a long time it was customary in Greek to Graecize foreign names, for example:

- Ioannis Goutemvergios for Johannes Gutenberg

- Martinos Louthiros for Martin Luther

- Satovriándos for François-René de Chateaubriand

- Károlos Marx for Karl Marx

- Égelos (rare; but often the adjective egelianós ) for Georg WF Hegel

Especially places with a historical Greek diaspora and important cities ( e.g. Berlin = Verolíno , London = Londíno , Paris = Paríssi , New York = Néa Yórki , Moscow = Mós'cha , Vienna = Viénni , Odessa = Odissiós , Leipzig = Lipsía ) have im Greek engraved names. Even after the founding of the state in 1829, this homogenization was applied to the Greek national territory and later place names (often derived from Slavic, Turkish or Albanian) were replaced by ancient Greek names, sometimes also arbitrarily chosen Greek names.

In the Ionian Islands, for example, Italian place names and personal names were given Greek endings, sometimes posthumously, e.g. B. Marinos Charvouris for Count Marin Carburi de Cefalonie or Vikentios Damodos for Vicenzo Damodo . Many people changed their names themselves to show that they belonged to the Greek state, to which the Ionian Islands belonged from 1864, e.g. B. Marinos Korgialenios from Corgialegno , who was then living in London.

Foreign names with few vowels are perceived as cakophonic , so that difficult first names of foreigners in Greece are Graecised ( e.g. Ernestos for Ernst ), just as difficult Greek first names have common and official pet forms ( Kostas , Kostis or Dinos for Konstantinos ).

Outside of Greece, there were isolated examples in the 19th century for the Graecization of first names and surnames, as in the case of the philhellenic writer Marie Espérance von Schwartz , who used the pseudonym "Elpis Melena" ( έλπίς elpis, ancient Greek, hope (espérance) ' and μέλαινα mélaina , the black one) used.

See also

literature

- The Graecization of Bavarian place names . In: Michaela Ofitsch, Christian Zinko (eds.): Studia Onomastica et Indogermanica. Festschrift for Fritz Lochner von Hüttenbach on his 65th birthday . Graz 1995, p. 215–227 (works from the department “Comparative Linguistics” Graz 9).

Individual evidence

- ↑ hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de

- ↑ welt.de

- ^ Wilhelm Gemoll : Greek-German school and hand dictionary. Munich / Vienna 1965.

- ↑ Erich Pertsch: Langenscheidts Large School Dictionary Latin-German. Langenscheidt, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-468-07201-5 .

- ↑ Disguised literature ( Memento from February 1, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ see doi: 10.3931 / e-rara-3515