Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism [ ʀənɛˈsɑ̃s ] is the modern name for a powerful intellectual movement in the Renaissance period , which was first suggested by Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374). It had a prominent center in Florence and spread over most of Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

First and foremost, it was a literary educational movement. The humanists advocated a comprehensive educational reform, from which they hoped an optimal development of human abilities through the combination of knowledge and virtue . Humanistic education should enable people to recognize their true destiny and to realize an ideal humanity by imitating classical models. A valuable, truthful content and a perfect linguistic form formed a unity for the humanists. Therefore, she paid special attention to the maintenance of linguistic expression. The Language and Literature fell a central role in humanistic education program. The focus was on poetry and rhetoric .

A defining characteristic of the humanist movement was the awareness of belonging to a new era and the need to distance oneself from the past of the previous centuries. This past, which was beginning to be called the “ Middle Ages ”, was contemptuously rejected by leading representatives of the new school of thought. The humanists considered the late medieval scholastic teaching system in particular to be a failure. They opposed the “barbaric” age of “darkness” to antiquity as the definitive norm for all areas of life.

One of the main concerns of the humanistic scholars was to gain direct access to this norm in its original, unadulterated form. This led to the demand for a return to the authentic ancient sources, expressed briefly in the Latin catchphrase ad fontes . Finding and publishing lost works of ancient literature, which was pursued with great commitment and led to spectacular successes, was considered particularly meritorious. With the discovery of many text witnesses , knowledge of antiquity was dramatically expanded. The fruits of these efforts were made available to a wider public thanks to the invention of printing . As a result, the influence of the cultural heritage of antiquity on many areas of the life of the educated greatly increased. In addition, the Renaissance humanists created the prerequisites and foundations for ancient studies with the discovery and development of manuscripts, inscriptions, coins and other finds . In addition to cultivating the learned languages Latin and Greek , they also dealt with vernacular literature and gave it significant impulses.

Concept history

The term “ humanism ” was introduced by the philosopher and education politician Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer (1766–1848). Niethammer's 1808 published pedagogical campaign pamphlet The Controversy of Philanthropinism and Humanism in the Theory of Educational Teaching of Our Time caused a sensation. He called humanism the basic pedagogical attitude of those who do not judge the subject matter from the point of view of its practical, material usability, but strive for education as an end in itself independent of considerations of usefulness. The acquisition of linguistic and literary knowledge and skills play a central role. A decisive factor in the learning process is the stimulation through intensive study of “classic” role models that you imitate. This educational ideal was the traditional one that has prevailed since the Renaissance. Therefore, around the middle of the 19th century, the intellectual movement that had formulated and implemented the program of an education conceived in this way in the Renaissance epoch was called humanism. As a cultural-historical term for a long period of transition from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period , Georg Voigt established “humanism” in his work The Revival of Classical Antiquity or the First Century of Humanism .

The word “humanist” is first attested towards the end of the 15th century, initially as a professional title for holders of relevant chairs , analogous to “jurist” or “ canonist ” ( canon lawyer). It was not until the early 16th century that it was also used for non-university educated people who saw themselves as humanistae .

Self-image and goals of the humanists

The educational program and its literary basis

The starting point of the movement was the concept of humanity (Latin humanitas "human nature ", "what is human, what distinguishes man"), which was formulated by Cicero in antiquity . The educational efforts described by Cicero as studia humanitatis aimed at the development of humanitas . In ancient philosophical circles - especially with Cicero - it was emphasized that humans differ from animals through language. This means that by learning and cultivating linguistic communication, he lives his humanity and lets the specifically human emerge. Therefore the idea was obvious that the cultivation of the linguistic ability to express themselves makes a person into a person in the first place, whereby it also elevates him morally and enables him to philosophize. From this one could conclude that the use of language at the highest attainable level is the most basic and most distinguished activity of human beings. From this consideration, the term studia humaniora ("the more [than other subjects] human-appropriate studies" or "the studies leading to higher humanity") arose in the early modern period to denote education in the humanistic sense.

From this perspective, language emerged as an instrument of self-expression of human rationality and the unlimited ability of humans to convey meanings. At the same time, language appeared as the medium with which man not only experiences his world, but also constitutes it. Starting from such a train of thought came the humanists to believe that between the quality of linguistic form and the quality of the information communicated by them content exists a necessary connection, especially that written in bad style text not to be taken seriously and its author also content Barbarian was . Therefore, the medieval Latin was heavily criticized, with only the classical models, especially Cicero, forming the standard. In particular, the technical language of scholasticism , which had moved far away from classical Latin, was despised and mocked by the humanists. One of their main concerns was to cleanse the Latin language of “barbaric” adulterations and restore its original beauty. The art of language (eloquentia) and wisdom should form a unit. According to humanist belief, studies in all fields thrive when language is in bloom and decay in times of linguistic decline.

Accordingly, rhetoric as the art of linguistic elegance was upgraded to the central discipline. In this area, alongside Cicero, Quintilian was the decisive authority for the humanists. One consequence of the increased appreciation of rhetoric was the rhetoric of all forms of communication, including manners. Because many spokesmen of the humanist movement were rhetoric teachers or appeared as speakers, the humanists were often simply called "speakers" (oratores) .

One problem was the tension between the generally positively assessed art of language and the philosophical or theological endeavor to find the truth. The question arose as to whether an unreserved affirmation of eloquence was justified, although rhetorical brilliance can be misused for deception and manipulation. The objection that eloquence is inevitably connected with lies and that the truth speaks for itself even without oratory ornamentation was taken seriously by the humanists and discussed controversially. Proponents of rhetoric proceeded from the basic humanist conviction that form and content cannot be separated, that valuable content requires beautiful form. They believed that good style was a sign of appropriate thinking, and that unkempt language was also unclear. This attitude dominated, but there were also advocates of the counter-thesis who believed that philosophy did not need eloquence and that the search for truth took place in an area free of eloquence.

The cultivation of language from the point of view of the humanists reached its peak in poetry, which was therefore highly valued by them. How was for poetry for prose Cicero Virgil the relevant model. The epic was considered the crown of poetry , so many humanists tried to renew the classical epic. The epics were often commissioned by rulers and served to glorify them. Occasional poetry was also widespread, including birthday, wedding and mourning poems. Poetic travelogues ( Hodoeporica ) were popular north of the Alps . According to the ideal of the poeta doctus, the poet was expected to have the technical knowledge of a universally educated person, which should include both cultural, scientific and practical knowledge. The art of sophisticated literary correspondence and literary dialogue were also greatly appreciated . Dialogue was considered an excellent means of exercising acumen and the art of reasoning. Letters were often collected and published; they then had a belletristic character, were partly edited for publication or fictitious. Their distribution also served the self-promotion and self-stylization of their authors.

Anyone who adopted such a point of view and was able to express themselves orally and in writing in classical Latin elegantly and without errors was regarded by the humanists as one of their own. A humanist was expected to master Latin grammar and rhetoric, to be familiar with ancient history and moral philosophy as well as ancient Roman literature, and to be able to write Latin poetry. The rank of the humanist among his peers depended on the extent of such knowledge and above all on the elegance of its presentation. Knowledge of Greek was very welcome, but not necessary; many humanists only read Greek works in Latin translation.

The enduring international supremacy of Latin in education has been attributed to its aesthetic perfection. Despite this dominance of Latin, some humanists also tried to use the spoken language of their time, the vernacular . In Italy, the suitability of Italian as a literary language was an intensely debated topic. Some humanists viewed the vernacular, the volgare , as in principle inferior, as it was a corrupt form of Latin and thus a result of the decline in the language. Others saw Italian as a young, developable language that required special care.

The intense humanistic interest in language and literature extended to the oriental languages, especially Hebrew . This formed a starting point for the participation of Jewish intellectuals in the humanist movement.

Since the humanists were of the opinion that as many people as possible should be educated, women were free to actively participate in humanistic culture. Women emerged primarily as patrons , poets and authors of literary letters. On the one hand, their achievements received rave reviews, on the other hand, some of them also had to deal with critics who reprimanded their activities as unfeminine and therefore unseemly.

The basic requirement of the educational program was the accessibility of the ancient literature. Many of the works known today were lost in the Middle Ages. Only a few copies of them had survived the fall of the ancient world and were only available in rare copies in monastery or cathedral libraries. These texts were largely unknown to medieval scholars before the beginning of the Renaissance. The humanistic "manuscript hunters" searched the libraries with great zeal and discovered a large number of works. Their successes were enthusiastically applauded. As a rule, however, the finds were not ancient codices , but only medieval copies. Only a few of the ancient manuscripts survived the centuries. The vast majority of ancient literature that has survived to this day was saved by the copying activity of the medieval monks, despised by the humanists.

Philosophical and religious aspects

Ethics dominated philosophy . Logic and metaphysics faded into the background. The vast majority of humanists were more philologists and historians than creative philosophers. This was due to their conviction that knowledge and virtue arise from direct contact of the reader with the classical texts, provided that they are accessible in an unadulterated form. There was a conviction that an orientation towards role models was necessary for the acquisition of virtue. The aspired qualities were rooted in pagan antiquity, they supplanted Christian medieval virtues such as humility . The humanistic ideal of personality consisted in the connection between education and virtue.

There are also other features that are used to characterize the humanistic view of the world and man. These phenomena, which one tries to grasp with catchwords like “ individualism ” or “autonomy of the subject”, however, refer to the Renaissance in general and not just specifically to humanism.

In earlier stages of the scientific study of Renaissance culture, it was often claimed that a characteristic of the humanists was their distant relationship with Christianity and the Church, or that it was even an anti-Christian movement. Jacob Burckhardt viewed humanism as atheistic paganism, while Paul Oskar Kristeller only stated that religious interest was being pushed back. Another line of interpretation distinguished between Christian and non-Christian humanists. The latest research paints a differentiated picture. The humanists proceeded from the general principle of the universal exemplary nature of antiquity and also included the “ pagan ” religion. Therefore they usually had an unbiased, mostly positive relationship with ancient “paganism”. It was customary for them to present Christian content in classical, antique garb, including relevant terms from ancient Greek and Roman religion and mythology . Most of them could reconcile this with their Christianity. Some were probably only Christians by name, others pious by church standards. Their ideological positions were very different and in some cases - also for reasons of opportunity - vague, unclear or fluctuating. Often they sought a balance between opposing philosophical and religious views and tended to syncretism . There were among them Platonists , Aristotelians , Stoics , Epicureans and followers of skepticism , clergy and anti-clericals.

A powerful concept was the teaching of the "old theologians" (prisci theologi) . It said that great pre-Christian personalities - thinkers like Plato and wisdom teachers like Hermes Trismegistus and Zarathustra - had acquired a precious wealth of knowledge about God and creation thanks to their efforts of knowledge and divine grace. This "old theology" anticipated an essential part of the worldview and ethics of Christianity. Therefore, the teachings of such masters also have the status of sources of knowledge from a theological point of view. A spokesman for this form of reception was Agostino Steuco , who coined the term philosophia perennis (everlasting philosophy) in 1540 . This is understood to mean the conviction that the central teachings of Christianity can be grasped philosophically and that they corresponded to the wisdom teachings of antiquity.

Often the humanists complained about the ignorance of the clergy and especially of the religious. There were indeed monks among the humanists, but in general monasticism - especially the mendicant orders - was a main opponent of humanism, because it was deeply rooted in an ascetic , volatile mindset, which was characterized by skepticism towards secular education. With their ideal of cultivated humanity, the humanists distanced themselves from the image of man that dominated conservative circles and especially in the monastic order, which was based on poverty, sinfulness and man's need for salvation. The uncultivated monk, who lets ancient manuscripts go to waste in the dirt of his ailing monastery, represented the typical enemy image of the humanists.

The general misery of human existence, omnipresent in medieval thought, was indeed aware of the humanists and was thematized by them, but they did not, like the monks, draw the conclusion from it to focus entirely on the Christian expectation of the hereafter. Rather, a positive, sometimes enthusiastically expressed assessment of human qualities, achievements and possibilities asserted itself in their milieu. The idea was widespread that the cultured person was like a sculptor or poet, since he formed himself into a work of art. This was connected with the idea of the deification of man to be striven for, to which man is by his nature predisposed. Such an unfolding of his possibilities he could realize in freedom and self-determined. A spokesman for the optimistic trend was Giannozzo Manetti , whose program On the Dignity and Excellence of Man, completed in 1452, emphasizes two key concepts in humanistic anthropology , dignitas (dignity) and excellentia (excellence). In addition to the dominant, confident view of the world and man, there was also the skepticism of some humanists who pointed to the experience of human weakness, folly and frailty. This led to controversial debates.

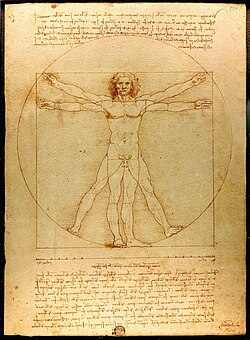

Several qualities were named as characteristics and evidence of the dignity of man and his unique special position in the world: his ability to know everything; his nearly unlimited research and inventiveness; the language skills with which he can express his knowledge; his competence to order the world and his associated claim to power. With these qualities man appeared like a little god whose mission is to act as a knowing, ordering and shaping power on earth. An essential aspect was the position of man in the "middle" of the world, in the midst of all the things to which he is related, between which he mediates and which he connects with one another.

There was a contradiction between humanism and the Reformation with regard to the assessment of man's ability to take his fate into his own hands . This showed itself particularly sharply in the dispute over the free will towards God. According to the humanistic understanding, man turns to or from God through the power of his free will. Martin Luther protested against this in his pamphlet De servo arbitrio , in which he vehemently denied the existence of such free will.

Many cosmopolitan humanists like Erasmus and even Reuchlin turned their backs on the Reformation. The questions raised by Luther, Zwingli and others were too much for them in the realm of dogmatic medieval thought; the renewed dominance of theology among the sciences deterred them. Other humanists broke away from ancient studies or only used them to interpret the Bible, also because they no longer wanted to orientate themselves on Italian models for political and religious reasons. Rather, they actively intervened in the denominational controversy and used the German language. This is how a national humanism emerged, especially among Luther supporters like Ulrich von Hutten .

Understanding of history

Renaissance humanism produced important historical theoretical works for the first time ; previously there had been no systematic examination of questions of historical theory.

While in the preceding period the understanding of history was strongly influenced by theology, humanistic historiography brought about a detachment from the theological perspective. The historical event was now explained internally, no longer as the fulfillment of the divine plan of salvation. Here, too, a central aspect was the humanistic emphasis on ethics, the question of correct, virtuous behavior. As in ancient times, history was considered a teacher. The exemplary attitudes and deeds of heroes and statesmen, impressively described in historical works, were intended to encourage imitation. The wisdom of the role models was expected to provide impetus for solving contemporary problems. For the historians, there was a tension between their literary creative drive and moral goal on the one hand and the requirement of truthfulness on the other. This problem was discussed controversially.

A major innovation was the periodization . The "re-establishment" of the idealized ancient culture led to a new division of cultural history into three main epochs: antiquity, which produced the classical masterpieces, the subsequent "dark" centuries as a period of decline and the era of regeneration initiated by humanism, which was the present Golden Age was glorified. From this three-part scheme, the common division of Western history into ancient, medieval and modern times arose. It meant a partial turning away from the previously prevailing view of history, which was determined by the notion of the translatio imperii , the fiction that the Roman Empire and its culture would continue to exist until the end of the world. Antiquity was increasingly perceived as a closed epoch, with a distinction between a heyday that lasted until the fall of the Roman Republic and a decadence that began in the early imperial period . This new periodization, however, only related to cultural development, not to political history. The capture and sacking of Rome by the Goths in 410, a more culturally important than militarily significant event, was cited as a serious turning point. The death of the late antique scholar and writer Boethius (524/526) was also mentioned as a turning point because he was the last ancient author to write good Latin.

A new historical criticism is connected with periodization. The humanistic perception of history was determined by a double basic feeling of distance: on the one hand, a critical distance to the immediate past, which was rejected as "barbaric", on the other hand, a distance from the ancient dominant culture due to the temporal distance, whose renewal was only possible to a limited extent under completely different conditions. In connection with the humanistic source criticism, this awareness enabled a higher sensitivity for historical processes of change and thus for historicity in general. The language was recognized as a historical phenomenon and began to classify the ancient sources historically and thus to relativize them. This was a development in the direction of the objectivity requirement of modern history. However, this was opposed to the basic rhetorical disposition and moral objectives of humanistic historiography.

In many cases, the historiography and historical research of the humanists was combined with a new kind of national self-confidence and a corresponding need for demarcation. In the reflection on national identity and in the folk typology, there were many glorifications of the own and the devaluation of the foreign. The humanistic nation discourse received a polemical orientation as early as the 14th century with Petrarch's insults against the French . When scholars saw themselves as representatives of their peoples, comparisons were made and rivalries fought. The fame of their countries was a major concern of many humanists. Italians cultivated pride in their special status as descendants of the classic ancient models and in the international dominance of the language of Rome. They took up the ancient Roman contempt for the “barbarians” and looked down on the peoples whose ancestors had once wiped out ancient civilization during the migration of the peoples . Patriotic humanists of other origins did not want to be left behind in the competition for fame and rank. They tried to prove that their people were no longer barbaric, because it had risen to a higher culture in the course of its history or had been led there by the current ruler. Only then did it become a nation. Another strategy consisted in contrasting the naturalness of one's own ancestors, which were considered unspoiled, as a counter-image to the decadence of the ancient Romans.

Imitation and self-reliance

A difficult problem arose from the tension between the demand for the imitation of classical ancient masterpieces and the pursuit of one's own creative achievement. The authority of the normative role models could seem overwhelming and inhibit creative impulses. The danger of a purely receptive attitude and the associated sterility was perceived and discussed by innovatively minded humanists. This led to rebellion against the overwhelming power of norms. The scholars, who condemned any deviation from the classical model as a phenomenon of decline and barbarization, were of a different opinion. These participants in the discourse argued aesthetically. For them, leaving the framework set by imitating an unsurpassable pattern was synonymous with an unacceptable loss of quality. The examination of the problem of imitation and independence occupied the humanists during the entire epoch of the Renaissance. The question was whether it was even possible to match the revived ancient models or even to surpass them with your own original works. The comparison between the achievements of the “moderns” and those of the “ancients” gave rise to cultural and historical reflection and resulted in different assessments of the two ages. In addition, general questions arose about the justification of authority and norms and the valuation of past and present, tradition and progress. The opinion was widespread that one should enter into a productive competition (aemulatio) with antiquity .

The controversy arose primarily from " Ciceronianism ". The "Ciceronians" were stylists who not only considered ancient Latin as exemplary, but also declared Cicero's style and vocabulary to be decisive. They said that Cicero was unsurpassed and that the principle should be applied that in all things one should prefer the best. However, this restriction to imitating a single model met with opposition. Critics saw this as a slavish dependence and turned against the restriction of freedom of expression. A spokesman for this critical direction was Angelo Poliziano . He said that everyone should study the classics first, but then try to be themselves and express themselves. Extreme forms of Ciceronianism became the target of opposing ridicule.

Need for fame and rivalries

A distinctive trait of many humanists was their strong, sometimes exaggerated self-confidence. They worked for their own fame and fame, the literary "immortality". Their need for recognition was shown, for example, in the urge for the coronation of poets with the wreath of poets. An often trodden path to fame and influence was to bring the language skills acquired through humanistic training to bear in the service of the mighty. This resulted in diverse relationships of dependency between humanistic intellectuals and the rulers and patrons, by whom they were promoted and whom they served as propagandists. Many humanists were opportunistic, and their support for their patrons was for sale. They made their rhetorical and poetic skills available to those who could honor it. In the conflicts in which they took sides, tempting offers could easily persuade them to change fronts. They believed that with their eloquence they had the decision about the fame and fame of a pope, prince or patron in their hands, and they played out this power. With ceremonial and ceremonial speeches, poems, biographies and historical works, they glorified the deeds of their clients and presented them as equal to those of ancient heroes.

The humanists were often at odds with one another. With invectives (diatribes) they attacked each other unrestrainedly, sometimes for trivial reasons. Even leading, famous humanists such as Poggio, Filelfo and Valla polemicized excessively and didn’t let the opponent down. The adversaries portrayed one another as ignorant, vicious and vicious and combined literary criticism with attacks on private life and even on the family members of the vilified.

Employment

Important professional fields of activity for humanists were librarianship, book production and the book trade. Some founded and ran private schools, others reorganized existing schools or worked as private tutors. In addition to the education sector, the civil service and in particular the diplomatic service offered professional opportunities and opportunities for advancement. Humanists found employment as councilors, secretaries and heads of chancelleries at princely courts or in city governments; some worked for their employers as publicists, key speakers, court poets , historians or prince tutors. The Church was an important employer; many humanists were clergy and received income from benefices or found employment in the church service. Some came from wealthy families or were supported by patrons. Few were able to earn a living as writers.

Initially, humanism was far removed from university operations, but in the 15th century humanists were increasingly appointed to chairs for grammar and rhetoric in Italy, or special chairs were created for humanistic studies. There were separate professorships for poetics (poetry theory). By the middle of the 15th century, humanistic studies were firmly established in Italian universities. Outside Italy, humanism was not able to establish itself permanently in universities until the 16th century.

Italian humanism

The Italian Renaissance humanism was formed in the course of the first half of the 14th century and its main features were developed around the middle of the century. Its end as an epoch came when its achievements had become a matter of course in the 16th century and no new groundbreaking impulses came from it. Contemporaries saw the catastrophe of the Sacco di Roma , the sack of Rome in 1527, as a symbolic turning point . According to today's classification, the high renaissance ended around that time in the fine arts and at the same time the heyday of the lifestyle associated with renaissance humanism. Italian humanism remained alive until the end of the sixteenth century.

Pre-humanism

The term “pre-humanism” (pre-humanism, protohumanism), which is not precisely defined, is used to describe cultural phenomena in the 13th and early 14th centuries that point to Renaissance humanism. Since this trend did not shape their time, one cannot speak of an “epoch of pre-humanism”, but only of individual pre-humanistic phenomena. The term is also controversial; Ronald G. Witt thinks it is inappropriate. Witt thinks it is already about humanism. According to this, Petrarch, who is considered the founder of humanism, is a "third generation humanist".

“Pre-humanism” or pre-Renaissance humanism originated in northern Italy and developed there in the 13th century. The impulse came from the reception of ancient poetry. When admirers of ancient poetry began to aggressively justify the “pagan” masterpieces against the criticism of conservative ecclesiastical circles, a new element was added to the conventional cultivation of this educational material that can be described as humanistic. The Paduan scholars and poets Lovato de 'Lovati (1241–1309) and Albertino Mussato (1261–1329), who already worked on philology, played a pioneering role, as did the poet and historian Ferreto de' Ferreti († 1337), who was active in Vicenza owed its clear and elegant style to the imitation of the models Livius and Sallust . Mussato, who wrote the reading tragedy of Ecerini based on the model of Seneca's tragedies , received the “ Poets' Crown ” in 1315 , renewing the ancient custom of adding a laurel wreath to outstanding poets . He believed that classical ancient poetry was of divine origin. Elements of Renaissance humanism were anticipated at that time.

Beginnings

Renaissance humanism began around the middle of the 14th century with the activities of the famous poet and antiquity enthusiast Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374). In contrast to his predecessors, Petrarch stood in sharp and polemical opposition to the entire scholastic education system of his time. He hoped for the beginning of a new cultural bloom and even for a new age. This should be linked not only culturally but also politically to antiquity, to the Roman Empire . Petrarch therefore enthusiastically supported the coup d'état of Cola di Rienzo in Rome in 1347 . Cola was self-educated, fascinated by Roman antiquity and a brilliant speaker, with which he partially anticipated humanistic values. He was the leading figure of an anti-nobility current that sought an Italian state with Rome as its center. The political dreams and utopias failed because of the balance of power and Cola's lack of a sense of reality, but the cultural side of the renewal movement, represented by the politically more cautious Petrarch, prevailed over the long term.

Petrarch's success was based on the fact that he not only articulated the ideals and longings of many educated contemporaries, but also embodied the new zeitgeist as a personality. With him, the most striking features of Renaissance humanism are already fully pronounced:

- the idea of a model of the ancient Roman state and social order

- Sharp rejection of scholastic university operations, that is, of Aristotelianism that dominated the late Middle Ages . Aristotle is respected as an ancient classic, but his medieval interpreters, especially Averroes , have been heavily criticized. Ultimately, this amounts to a fundamental criticism of Aristotle.

- Rejection of the speculative metaphysics and theology of the late Middle Ages and the logical tinkering that was felt to be senseless. As a result, philosophy is largely reduced to the doctrine of virtue, whereby it depends on the practice of virtue, not on the theoretical understanding of its essence.

- Rediscovery of lost classical texts, collecting and copying of manuscripts, creation of an extensive private library. Return to direct, impartial contact with the ancient texts through liberation from the monopoly of interpretation by church authorities. Limitless admiration for Cicero.

- The encounter with the ancient authors is seen as a dialogue. The relationship of the reader to the author or to the book in which the author is present is dialogical. In the daily dialogue with the authors, the humanist receives answers to his questions and norms for his behavior.

- Fight against the medical and legal faculties prevailing scientific concepts. Doctors are accused of ignorance and charlatanism, while lawyers are accused of subtlety.

- Desire for confirmation and fame, strong self-confidence, sensitivity, readiness for violent polemics against real or supposed envious people and enemies.

The somewhat younger poet and writer Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) was strongly influenced by Petrarch . He also discovered manuscripts of important ancient works. His basic humanistic attitude is particularly evident in his defense of poetry. He is convinced that poetry deserves the highest rank not only from a literary point of view, but also because of its role in the attainment of wisdom and virtue. Ideally, it combines the art of language and philosophy and achieves its perfection. Boccaccio regarded the pagan poets as theologians because they had proclaimed divine truths. In poetic language he did not see an instrument of the human, but of the divine in man.

The heyday in Florence

Florence as an outstanding place of art and culture was the nucleus of humanism. From there came decisive impulses for philology as well as for philosophy and humanistic historiography. Humanists who came from or trained there in Florence carried their knowledge to other centers. The prominent role of Florentine humanism remained until the 1490s. Then, however, the influence of the anti-humanist monk Savonarola , which dominated the period 1494–1498, had a devastating effect on Florentine cultural life, and the turmoil that followed hampered recovery.

Florence did not have a strong scholastic tradition as the city did not have a top university. Most of the intellectual life took place in relaxed discussion circles. This open atmosphere offered favorable conditions for a humanistic culture of discussion. The office of Chancellor of the Republic had been occupied by humanists since Coluccio Salutati , who held it from 1375 to 1406. It offered the incumbent the opportunity to demonstrate to the public the merits of interweaving political and literary activity and thus the political benefits of humanism. Salutati made use of this opportunity with great success in his missives and political writings. Through his scientific, cultural and political achievements, he made Florence the main center of Italian humanism, of which he was one of the leading theorists.

Another great benefit to Florentine humanism was the patronage of the Medici family , who played a dominant role in the city's political and cultural life from 1434 to 1494. Cosimo de 'Medici ("il Vecchio", † 1464) and his grandson Lorenzo ("il Magnifico", † 1492) distinguished themselves through their generous support of the arts and sciences. Lorenzo, himself a gifted poet and writer, was considered the model of a Renaissance patron.

However, the Platonic Academy allegedly founded by Cosimo on the model of the ancient Platonic Academy did not exist in Florence as an institution; the term "Platonic Academy of Florence" was only invented in the 17th century. In fact, it was only the group of students of the important Florentine humanist Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499). Ficino, who was supported by Cosimo, sought a synthesis of ancient Neoplatonism and Catholic Christianity. With great diligence he devoted himself to the translation of ancient Greek writings into Latin and the commentary on the works of Plato and ancient Platonists.

To Ficino's circle of comprehensively educated, Arabic and Hebrew competent belonged to Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), including the Islamic advocated the reconciliation of all philosophical and religious traditions and a prominent representative of the Christian Kabbalah was. Pico's speech on human dignity is one of the most famous texts of the Renaissance, although it was never delivered and was only published after his death. It is regarded as the program font of humanistic anthropology. Pico derived the dignity of man from the freedom of will and choice , which distinguishes man and distinguishes him from all other creatures and thus establishes his uniqueness and likeness to God .

Outstanding representatives of Florentine humanism were also Niccolò Niccoli († 1437), an avid book collector and organizer of the procurement and research of manuscripts; Leonardo Bruni , a student of Salutati and, as Chancellor 1427–1444, continued his policy, author of an important account of the history of Florence; Ambrogio Traversari (1386–1439), who translated from the Greek and, as a monk, was an exceptional figure among humanists; his pupil Giannozzo Manetti (1396-1459), who translated from Hebrew, among other things, and Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494), who wrote Italian, Latin and Greek and excelled in textual criticism . Other important humanists who worked temporarily in Florence were Francesco Filelfo , Poggio Bracciolini and Leon Battista Alberti . Vespasiano da Bisticci (1421–1498) was the first large-scale bookseller. He was extraordinarily resourceful in obtaining manuscripts of all kinds and had them copied in calligraphy by dozens of copyists to meet the demands of humanists and princes who built libraries. He also wrote a collection of biographies of outstanding personalities of his time, with which he strongly influenced posterity's ideas of Renaissance humanism.

The use of humanistic journalism in the struggle for a republican constitution and against the “tyrannical” sole rule of a ruler is referred to as “ civic humanism ”. In addition, there was a general appreciation of the civic creative will among the representatives of this trend compared to retreating into a peaceful private life, later also the affirmation of bourgeois prosperity, which was no longer viewed as an obstacle to virtue, and an appreciation of Italian as a literary language. This attitude asserted itself in Florence, with the Chancellor Coluccio Salutati playing a pioneering role. The republican conviction was effectively represented rhetorically by the Chancellor Leonardo Bruni, substantiated in detail and underpinned by the philosophy of history. The main focus was on defending against the expansion policy of the Milanese Visconti , which threatened Florence . The Florentines emphasized the advantages of the freedom prevailing in their system, the Milanese insisted on order and peace, which were owed to the subordination to the will of a ruler. This contrast was sharply worked out in the journalism of both sides.

The term “citizen humanism” coined by the historian Hans Baron from 1925 onwards has become established, but is controversial in research. Opponents of the “baron thesis” claim that Baron idealized the politics of the humanist Florentine chancellors and followed their propaganda, that he would draw far-reaching conclusions from his observations and that his comparison with the history of the 20th century was not permissible. In addition, he did not take into account the imperialist character of Florentine politics.

Rome

For the humanists, Rome was the epitome of the venerable. As the center of humanism, however, Rome lagged behind Florence and did not begin to flourish until the mid-15th century. The strongest suggestions came from Florence and its surroundings. Most of the humanists living in Rome were dependent on a position at the Curia , mostly in the papal chancellery , sometimes as secretaries of the popes. Many were secretaries to cardinals. Some of the coveted offices in the firm were salable positions. Much depended on how humanist-friendly the ruling Pope was.

Pope Nicholas V (1447–1455) gave Roman humanism a strong boost with his far-sighted cultural policy. He brought well-known scholars and writers to his court, arranged for translations from the Greek and, as an avid book collector, created the basis for a new Vatican library . Pius II (Enea Silvio de 'Piccolomini, 1458–1464) had emerged as a humanist before his papal election, but as Pope did relatively little to promote culture. Sixtus IV (1471–1484), Julius II (1503–1513) and Leo X (1513–1521) proved to be very humanist- friendly. However, a decline began under Leo. The Sacco di Roma suffered a serious setback in 1527.

Leading figures in Roman humanism in the 15th century were Poggio Bracciolini , Lorenzo Valla , Flavio Biondo and Julius Pomponius Laetus . Poggio († 1459) was the most successful discoverer of manuscripts and gained a high reputation for his spectacular finds. He wrote moral-philosophical dialogues, but also hateful diatribes. The literary collections of his letters, which are valuable as sources of cultural history, received a lot of attention. Like many other scholars of foreign origin, Poggio saw Rome only as a temporary residence. Valla († 1457), fatally enemies of Poggio, was a professor of rhetoric. He made significant advances in language analysis and source criticism, and stood out for his unconventional views and provocation. Biondo († 1463) accomplished groundbreaking achievements in the field of archeology and historical topography of Italy, especially Rome. He also included medieval Italy in his research and worked on the systematic recording of remains from antiquity. With his encyclopedia Roma illustrata he created a standard work of antiquity. In this area later also Pomponius († 1498) worked, who as a university professor inspired a large group of students for classical studies. Around 1464 he founded the oldest Roman academy, the Accademia Romana , a loose community of scholars. One of his students was the excellent archaeologist Andrea Fulvio. In 1468 the academy got into a serious crisis and was temporarily closed because Pope Paul II suspected individual humanists of rebellious activities. The harsh action taken by this Pope against the Academy was an atypical, temporary disruption in the otherwise rather unproblematic relationship between the Curia and humanism; in the college of cardinals the accused humanists found zealous and successful advocates.

Of the younger Roman humanist communities of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the best-known were dedicated to cultivating a Latinism based on Cicero's model and to neo-Latin poetry . Rome was a stronghold of Ciceronianism; in it the needs of the papal chancellery met the inclinations of the humanists. Even theological texts were formulated using Cicero's vocabulary. The form and content of the self-portrayal of the papacy was imbued with the antiquing spirit of the humanists at the Curia. In their texts, Christ and the saints were praised like ancient Roman heroes, the church appeared as the successor to the Roman Empire and the popes were worshiped like new emperors. So pagan and Christian culture merged into one.

The strictly Ciceronian-minded humanists Pietro Bembo († 1547) and Jacopo Sadoleto († 1547) gained considerable influence at the Curia as Leo X's secretaries. Bembo, who came from the Venetian aristocracy, also worked as a historian and rose to cardinal. In his influential main work Prose della volgar lingua in 1525 he presented a grammar and style theory of the Italian literary language. He established Petrarch for poetry and Boccaccio for prose as classic models to be copied in Italian.

Naples

In the Kingdom of Naples , humanism thrived on the favor of kings. The humanistic court historiography served to glorify the ruling Aragon dynasty.

King Robert of Anjou , who ruled Naples from 1309 to 1343, was inspired by Petrarch to make educational efforts and set up a library, but it was only Alfonso V of Aragón (Alfons I of Naples, 1442-1458), the most glamorous patron under the princes of Italy at the time, humanism made Naples its home. He offered humanists who had made themselves unpopular elsewhere because of their bold and challenging demeanor a place of work in his empire. One of his favorites was Valla, who lived temporarily in the Kingdom of Naples and, under Alfonso's protection, was able to direct violent attacks against clergy and monasticism. During this time Valla also achieved his most famous scientific achievement: he exposed the Donation of Constantine , an alleged deed of donation from Emperor Constantine the Great for Pope Silvester I , as a medieval forgery. This was at the same time a blow to the papacy, a triumph of humanistic philology and a favor to King Alfonso, who was at odds with the Pope. In Naples, Valla also wrote the Elegantiarum linguae Latinae libri sex (Six books on the subtleties of the Latin language) , a basic style manual for the standardization of humanistic Latin, in which he described the virtues of the Latin language in detail. Also Antonio Beccadelli , who had made himself hated by his sensational for its time erotic poetry in church circles, was allowed to be active in Naples. A loose circle of humanists formed around him, which - in a broad sense of the word - is known as the “Academy of Naples”.

Alfons' son and successor Ferdinand I (1458–1494) continued to promote humanism and established four humanistic chairs at the university. The actual founder of the academy was Giovanni Pontano († 1503), one of the most important poets among the humanists; after him it is called Accademia Pontaniana . It was characterized by a special openness and tolerance and a wide variety of approaches and research areas and became one of the most influential centers of intellectual life in Italy. The famous Naples-born poet Jacopo Sannazaro († 1530), who continued Pontano's tradition, worked at court and in the academy .

Milan

The Duchy of Milan , to which the university town of Pavia also belonged, provided humanism in the ducal chancellery and at the University of Pavia under the rule of the Visconti family , which lasted until 1447 . Otherwise there was a lack of initiators. More than anywhere else, the role of humanists as propagandists in the service of the ruling house was in the foreground in Milan. In this sense Antonio Loschi , Uberto Decembrio and his son Pier Candido Decembrio worked at the court. The most prominent humanist in the duchy was Francesco Filelfo († 1481), who distinguished himself through his perfect knowledge of the Greek language and literature and even wrote Greek poetry. Filelfo's many students have produced a number of classic editions. But he was not rooted in Milan, but only lived there because he had to leave Florence for political reasons, and returned to Florence in old age.

Under the ducal dynasty of Sforza , who ruled from 1450, humanistic culture also benefited from the political and economic upswing, but as the center of intellectual life, Milan stood behind Florence, Naples and Rome. The turmoil after the French conquest of the duchy in 1500 was devastating for Milanese humanism.

Venice

In the Republic of Venice , humanism was dependent on the goals and needs of the ruling nobility. Stability and continuity were desired, not the scholarly feuds and polemics common elsewhere against the scholastic tradition. Humanistic production was considerable in the 15th century, but it did not correspond to the political and economic weight of the Venetian state. A conservative and conventional basic trait was predominant; Scholars did solid academic work, but lacked original ideas and stimulating controversy. The Venetian humanists were defenders of the city's aristocratic system. Traditional religiosity and Aristotelianism formed a strong current. An outstanding and typical representative of Venetian humanism was Francesco Barbaro († 1454).

Later the most distinctive personality of the printer and publisher was Aldo Manuzio , who worked in Venice from 1491 to 1516 and also published Greek text editions. His production, the Aldinen , was groundbreaking for book printing and publishing throughout Europe. Manuzio's publishing house became the focus of Venetian humanism. The philologists met in the publisher's neo-academia . This “academy” was a discussion group, not a fixed institution.

Other centers

Humanism found generous sponsors in many places at the courts that competed culturally with one another. Among the rulers who were open to humanistic endeavors, the following stood out:

- in Rimini the educated condottiere and patron Sigismondo Malatesta († 1468), who gathered scholars and poets at his court

- in Mantua the marquis Gianfrancesco Gonzaga and Ludovico (Luigi) III. Gonzaga

- in the Duchy of Urbino the Condottiere and Duke Federico da Montefeltro († 1482), a student of the humanistic reform pedagogue Vittorino da Feltre ; he built a large and splendid library.

- in Ferrara Niccolò III. d'Este , Leonello d'Este and Ercole I. d'Este .

Greeks in Italy

Among the factors that influenced Italian humanism is the crisis of the Byzantine state , which ended with its collapse in 1453 . Greek scholars came to Italy temporarily or permanently, partly on political or church missions, partly to teach Greek to the humanists. Some decided to emigrate because of the catastrophic situation of their homeland, which was gradually conquered by the Turks. They contributed to the philological development and translation of the Greek classics. Large quantities of manuscripts were bought by Western collectors or their agents in the Byzantine Empire before its fall. In this distinguished himself Giovanni Aurispa out that in the early 15th century on his travels to the East, hundreds of manuscripts acquired and brought to Italy. There was a strong fascination with these texts because the humanists were convinced that all cultural achievements were of Greek origin.

In the West, a number of works by Greek-speaking philosophers had been translated into Latin as early as the 13th century. These late medieval translations usually followed the rigid “word for word” principle without regard to comprehensibility, let alone style. There was therefore an urgent need for new, fluently readable translations that were understandable even for non-specialists. Much of Greek literature first became accessible in the West through humanistic translations and text editions. These newly discovered treasures included Homer's epics , most of Plato's dialogues , tragedy and comedy, the works of famous historians and speakers as well as medical, mathematical and scientific literature.

Florence also played a pioneering role in this area. It all started with Manuel Chrysoloras , who arrived in Florence in 1396 as a teacher of Greek language and literature. He founded the humanistic translation technique and wrote the first Greek elementary grammar of the Renaissance. At the Council of Ferrara / Florence , the Byzantine delegation, which negotiated with the Council Fathers from 1438–39, included prominent scholars. Among them were Georgios Gemistos Plethon , who stimulated an in-depth examination of the differences between Aristotelian and Platonic philosophy and gave an impetus to the spread of Platonism, and Bessarion , a distinguished Platonist who emigrated to Italy and achieved the dignity of cardinals. Bessarion became a leading exponent of Greek culture in the Latin-speaking scholarly world. He built up the largest collection of Greek manuscripts in the West and donated his precious library to the Republic of Venice . To Bessarion's circle belonged Demetrios Chalkokondyles († 1511), who as a professor of Greek important humanists was one of his students; in 1488 he published the first printed Homer edition. Johannes Argyropulos , who was appointed to a philosophical chair in Florence in 1456, made fundamental contributions to Greek philology and to the understanding of Plato and Aristotle in Italy. Theodoros Gazes and Georg von Trebizond worked in Rome on a papal assignment as translators of philosophical and scientific works as well as the writings of the church fathers .

Balance of classical and literary achievements

The Italian humanists were mainly active as writers, poets and archaeologists. Therefore her main achievements are in the fields of literature, classical studies and the teaching of ancient educational goods. In addition to groundbreaking text editions, grammars and dictionaries, these include the foundation of epigraphy , which was initiated by Poggio Bracciolini, and numismatics . Humanists were also active as pioneers in the field of historical topography and regional studies . The enthusiasm for antiquity they sparked aroused a keen interest in the material remains of antiquity, which found particularly plentiful nourishment in Rome. Popes, cardinals and princes built up " collections of antiquities " which also served representational purposes: they could show wealth, taste and education.

With regard to the quality of linguistic expression in Latin, the Renaissance humanists set new standards that remained valid beyond their age. Her philological and literary work was also essential for the establishment of Italian as a literary language. Numerous previously lost literary works and historical sources from antiquity have been discovered, made available to the public, translated and commented on. Classical antiquity was established; Both philology and historical research, including archeology, received trend-setting impulses and were given their shape that would be valid for the following centuries. The demand for a return to the sources (“ad fontes”), to the authentic, became the starting point for the emergence of philological-historical science in the modern sense. It also had an impact on theology, because the humanistic philological approach was also applied to the Bible. This biblical research is known as Bible humanism . Biblical humanism, for which Lorenzo Valla gave the impetus, was usually associated with a polemical departure from scholastic theology.

Thanks to humanistic educational efforts, the previously extremely rare knowledge of Greek spread, so that for the first time since the fall of antiquity it was possible in the West to understand and appreciate the special characteristics of the Greek roots of European culture. The achievements of the Italian humanists and the Greek scholars working in Italy were groundbreaking. In the 16th century the teaching of Greek language and literature was established at the larger Western and Central European universities through their own chairs and was an integral part of the curriculum at many high schools. In addition, interest in Hebrew studies and the exploration of oriental languages and cultures as well as ancient Egyptian religion and wisdom arose.

Font reform

The Renaissance culture owed a fundamental reform of writing to the humanists. Petrarch already advocated writing that was “precisely drawn” and “clear”, not “extravagant” and “indulgent”, and that did not “irritate and tire” the eyes. The broken scripts common in the late Middle Ages displeased the Italian humanists. In this area too, they sought the solution by falling back on an older, superior past, but the alternative they chose, the humanistic minuscule , was not developed from an ancient font. It is based on the imitation of the early medieval Carolingian minuscule , in which many of the manuscripts found in ancient works were written. As early as the 13th century, the Carolingian minuscule was called littera antiqua ("old script"). Coluccio Salutati and above all Poggio Bracciolini contributed significantly to the design of the humanistic minuscule, which from 1400 assumed the form from which the Renaissance Antiqua emerged in book printing . In addition, Niccolò Niccoli developed the humanistic cursive on which the modern script is based. It was introduced to printing in 1501 by Aldo Manuzio.

Europe-wide expansion

From Italy, humanism spread across Europe. Italian carriers of the new ideas traveled north and established contacts with local elites. Many foreign scholars and students went to Italy for educational purposes and then carried the humanistic ideas to their home countries. The printing press and the lively international correspondence between the humanists also played a very important role in the spread of the new ideas. The intensive correspondence promoted the community awareness of the scholars. The councils ( Council of Constance 1414–1418, Council of Basel / Ferrara / Florence 1431–1445), which led to diverse international encounters, also favored the triumphant advance of humanism.

The willingness to accept the new ideas varied greatly in the individual countries. This can be seen in the different speed and intensity of the reception of humanistic impulses and also in the fact that in some regions of Europe only certain parts and aspects of humanistic ideas and attitudes towards life met with a response. In some places the resistance of conservative circles to the reform efforts was strong. Everything that was transmitted changed in the new context, the adaptation to regional conditions and needs took place in processes of productive transformation. Today we speak of the “diffusion” of humanism. This neutral expression avoids the one-sidedness of the also common terms “culture transfer” and “reception”, which emphasize the active and passive aspect of the processes.

North of the Alps, like the spread of humanism, its fading took place with a time lag. While modern representations of Italian Renaissance humanism only lead into the first half of the 16th century, research for the German-speaking area has established a continuity into the early 17th century. For the Central European educational and cultural history in the period between about 1550 and about 1620, the term "late humanism" has become established. The temporal delimitation of late humanism and its independence as an epoch are controversial.

German-speaking area and the Netherlands

In the German-speaking area, humanistic studies spread from the middle of the 15th century, and the Italians were the main model everywhere. In the initial phase, the courtyards and law firms emerged as centers. The people responsible for the spread were Germans who studied in Italy and brought Latin manuscripts with them when they returned home, and Italians who appeared as donors north of the Alps. The Italian humanist Enea Silvio de 'Piccolomini played a key role. Before he was elected Pope, he was a diplomat and secretary to King Frederick III from 1443 to 1455 . worked in Vienna. He became the leading figure of the humanist movement in Central Europe. His influence extended to Germany, Bohemia and Switzerland. In Germany he was regarded as a stylistic role model and was the most influential humanist writer until the late 15th century. One of the most important cultural centers north of the Alps was Basel, which had had a university since 1460 . In competition with Paris and Venice, Basel became the capital of humanistic printing in early modern Europe and, thanks to the open-mindedness and relative liberality that prevailed there, was a gathering point for religious dissidents, especially Italian emigrants, who brought in their scholarship in the 16th century.

The rediscovered Germania des Tacitus gave an impetus to the development of the idea of a German nation and a corresponding national feeling. This was expressed in the German praise, the appreciation of virtues considered typically German: loyalty, bravery, steadfastness, piety and simplicity ( simplicitas in the sense of unspoiltness, naturalness). Such self-assessment was a popular topic among German university speakers, it shaped the humanistic discourse about a German identity. The humanists emphasized the German possession of the empire (imperium) and thus the priority in Europe. They claimed that the nobility was of German origin and that the Germans were morally superior to the Italians and French. German ingenuity was also praised. They liked to refer to the invention of the art of printing, which was considered a German collective achievement. Theoretically, the claim to national superiority encompassed all Germans, but specifically the humanists only focused on the educated elite.

German and Italian "wandering humanists", including the pioneer Peter Luder , were active at German universities . The confrontation with the scholastic tradition, which the humanists opposed as "barbaric", was harder and tougher than in Italy, since scholasticism was deeply rooted in the universities and its defenders only slowly retreated. A large number of conflicts arose, which led to the emergence of a rich polemical literature. These disputes reached their climax with the polemics surrounding the publication of the satirical " dark man's letters ", which served to ridicule the antihumanists and caused a sensation from 1515 onwards. The University of Cologne was considered a stronghold of anti-humanist scholasticism, while Erfurt was a meeting point for German humanists. The new studia humanitatis was a foreign body in the conventional university system with its faculties, which was therefore not initially incorporated, but attached. The establishment of humanistic subjects and the appointment of the teaching staff there represented a challenge for the traditional teaching organization and university constitution. Often such decisions were made on the basis of interventions by the authorities.

In Germany and the Netherlands, the first outstanding representatives of an independent humanism, which emancipated itself from the Italian models, were Rudolf Agricola († 1485) and Konrad Celtis († 1508). Agricola impressed his contemporaries above all with his extraordinarily versatile personality, which made him a role model for the humanistic art of living. He combined scientific studies with artistic activity as a musician and painter and was characterized by his very optimistic view of human abilities and his restless pursuit of knowledge. Celtis was the first important neo-Latin poet in Germany. He was at the center of an extensive network of contacts and friendships that he created on his extensive travels and maintained through correspondence. His project of Germania illustrata , a geographical, historiographical and ethnological description of Germany, remained unfinished, but the preliminary studies were granted an intensive aftermath. By founding communities of scholars (sodalitates) in a number of cities, he strengthened the cohesion of the humanists.

The German King Maximilian I , elected in 1486, promoted the humanist movement as a patron and found enthusiastic supporters among the humanists who supported him in the pursuit of his political goals. In Vienna, Maximilian founded a humanistic poets college in 1501 with Celtis as director. It was part of the university and had four teachers who taught poetics, rhetoric, math and astronomy. The graduation was not a traditional academic degree, but a poet's coronation.

In the early 16th century, the Dutchman Erasmus von Rotterdam was the most respected and influential humanist north of the Alps. His endeavor to obtain a pure, unadulterated version of the New Testament by recourse to its Greek text was of great importance. His writings in the field of life counseling met with an extraordinarily strong response - also outside of scholarly circles. Erasmus lived in Basel from 1521 to 1529, where he published his works in collaboration with his friend, the publisher Johann Froben , and developed an intensive editing activity. Among the most famous spokesmen for the humanist movement in Germany at that time were the lawyers Konrad Peutinger (1465–1547) and Willibald Pirckheimer (1470–1530), who, in addition to their academic activities, also took on political and diplomatic tasks as imperial councilors . Peutinger wrote legal opinions on the economy, with which he became a pioneer of modern economics . The historians Johannes Aventinus (1477–1534) and Jakob Wimpheling (1450–1528) and the philosopher, Graecist and Hebraist Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522), who wrote the first Hebrew grammar, also had a pioneering effect . The historian and philologist Beatus Rhenanus (1485–1547) made a valuable contribution to the flourishing of German history with his critical judgment. The publicist Ulrich von Hutten (1488–1523) was the most prominent representative of militant political humanism; he combined humanistic scholarship with patriotic goals and a cultural-political nationalism. In the next generation, the Graecist and educational reformer Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560) held a prominent position; he was called Praeceptor Germaniae ("Germany's teacher"). As a science organizer, he had a lasting impact on the organization of schools and universities in the Protestant area; as the author of school and study books, he was pioneering in didactics.

In the German humanism of the 16th century, the emphasis was increasingly placed on school pedagogy and classical philology . From the middle of the century, humanistic material became compulsory in both Protestant and Catholic schools. This development led on the one hand to a strong broadening of education, but on the other hand to a schooling and scientification that pushed back the creative element of the original educational ideal. Ultimately, the one-sided concentration on the academic and academic reception of antiquity brought the impulse of Renaissance humanism to a standstill.

France

Petrarch spent a large part of his life in France. His polemics against French culture, which he considered inferior, aroused violent protests from French scholars. Petrarch stated that there were no speakers or poets outside of Italy, so there was no education in the humanistic sense. In fact, humanism did not gain a foothold in France until the late 14th century. A pioneer was Nikolaus von Clamanges († 1437), who taught rhetoric and gained fame from 1381 at the Collège de Navarre , the center of French early humanism. He was the only significant stylist of his time in France. In his later years, however, he distanced himself from humanism. His contemporary Jean de Montreuil (1354–1418), an admirer of Petrarch, internalized the humanistic ideals more sustainably. The influential theologian and church politician Jean Gerson (1363–1429) wrote Latin poems based on Petrarch's model, but was far removed from the ideas of the Italian humanists. The public impact of early French humanism remained small.

The turmoil of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) hampered the development of humanism. After the fighting ended, it flourished from the middle of the 15th century. The main contribution was initially made by the rhetoric teacher Guillaume Fichet , who set up the first printing press in Paris and published a textbook on rhetoric in 1471. He anchored Italian humanism at the University of Paris. Fichet's pupil Robert Gaguin († 1501) continued the work of his teacher and replaced him as the leading head of Parisian humanism. He maintained a consciously national history.

Classical studies in France gained momentum through the efforts of Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (Latin: Jacobus Faber Stapulensis , † 1536), who contributed significantly to the knowledge and research of the works of Aristotle with text editions, translations and commentaries. He also pursued philological Bible studies, which earned him the bitter hostility of Parisian theologians. Another important scholar of antiquity was Guillaume Budé (1468–1540), who did a great job as a Graecist and as an organizer of French humanism. His research on Roman law and his work De asse et partibus eius ( About the As and its parts , 1515), an investigation of coinage and the units of measurement of antiquity and at the same time economic and social history, were groundbreaking. Budé was secretary to Kings Charles VIII and Francis I and used his office to promote humanism. As head of the royal library, which later became the national library, he pushed ahead with its expansion. It was mainly on his initiative that the Collège Royal (later the Collège de France ) was founded, which became an important center of humanism. The Collège Royal formed a counterpoint to the anti-humanist tendency at the University of Paris, whose representatives were conservative theologians. The poet and writer Jean Lemaire de Belges , who was inspired by Italian Renaissance poetry, stood out among the literary humanists . Politically and culturally, like Budé and many other French humanists, he took a nationalist stance.

King Francis I, who ruled from 1515 to 1547, was considered by his contemporaries to be the most important promoter of French humanism. Numerous authors of the 16th century regarded the flowering of humanistic education as his merit.

England

In England, the beginnings of a humanistic way of thinking in the Franciscan milieu appeared as early as the 14th century . However, real humanism was not introduced until the 15th century. Initially French and Italian, and in the late 15th century also Burgundian-Dutch influence. A major promoter of humanism was Duke Humphrey of Gloucester (1390-1447).

At the universities - also thanks to the teaching activities of Italian humanists - humanistic thinking slowly asserted itself against the resistance of conservative circles in the course of the 15th century. At the same time, numerous non-church educational institutions (colleges, grammar schools ) were founded, which competed with the old church schools. In contrast to the Italian humanists, the English avoided a radical break with the scholastic tradition. They strived for an organic further development of the conventional system of university education by incorporating their new ideas.

Towards the end of the 15th century and after the turn of the century there was a marked boom in humanistic education. In the early 16th century, Erasmus became a great source of inspiration. One of the leading figures was the scholar John Colet (1467–1519), who had studied in Italy, was friends with Erasmus and emerged as the school founder. The royal court physician Thomas Linacre († 1524), who was also trained in Italy, spread knowledge of ancient medical literature among his colleagues. Linacre's friend William Grocyn († 1519) brought Bible humanism to England. The most famous representative of English humanism was the statesman and writer Thomas More († 1535), who worked as a royal secretary and diplomat and from 1529 assumed a leading position as Lord Chancellor . More's student Thomas Elyot published the state-theoretical and moral-philosophical work The boke Named the Governour in 1531 . In it he set out humanistic educational principles that contributed significantly to the development of the gentleman ideal in the 16th century.

In political theory , the strongest impulses came from Platonism in the 16th century. The English humanists dealt intensively with Plato's doctrine of a good and just state. They justified the existing aristocratic social order and tried to improve it by advocating a careful upbringing of the children of the nobility according to humanistic principles. Humanistic education should be one of the characteristics of a gentleman and political leader. This generally meritocratic order of values was not easily compatible with the principle of the rule of the hereditary nobility. The humanists asked themselves whether acquiring humanistic education could qualify them for advancement to positions normally reserved for nobles, and whether a member of the aristocratic ruling class unwilling to educate would jeopardize his inherited social rank, whether ultimately education or that Descent was decisive. The answers varied.

Iberian Peninsula

On the Iberian Peninsula , the social and educational-historical prerequisites for the development of humanism were relatively unfavorable, so its broad cultural impact remained weaker than in other regions of Europe. In Catalonia , the political connection with southern Italy that had arisen as a result of the expansion policy of the Aragonese Crown made it easier for humanist ideas to flow in, but there was no broad reception there either. A major obstacle was the widespread ignorance of the Latin language. Therefore, the reading of vernacular translations formed a focus of the examination of ancient culture. The translation work was in the 13th century at the instigation of King Alfonso X used. Juan Fernández de Heredia († 1396) arranged for works by important Greek authors ( Thucydides , Plutarch ) to be translated into Aragonese . Among the ancient Latin writings that were translated into the vernacular, works of moral philosophy were in the foreground; Seneca in particular was widely received. In the Kingdom of Castile , the poets Juan de Mena († 1456) and Iñigo López de Mendoza († 1458) founded a Castilian poetry based on the example of Italian humanist poetry and became classics. The introduction of rhetoric as a subject at the University of Salamanca in 1403 gave an important impetus to the maintenance of the Latin style .

Spanish humanism experienced its heyday at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th century. During this period his most important representative was the rhetoric professor Elio Antonio de Nebrija († 1522), who was trained in Bologna and who returned to his homeland in 1470 and began teaching at the University of Salamanca in 1473. With his textbook Introductiones Latinae, published in 1481, he promoted the humanistic reform of Latin teaching, created a Latin-Spanish and a Spanish-Latin dictionary, and published the first grammar of the Castilian language in 1492 .

Nebrija fought offensively for the new learning. The conflict with the Inquisition arose when he began to deal philologically with the Vulgate , the authoritative Latin version of the Bible. He wanted to check the translations of the biblical texts from Greek and Hebrew into Latin and apply the newly developed humanistic textual criticism to the Vulgate. This project brought the Grand Inquisitor Diego de Deza on the plan, who in 1505 confiscated Nebrija's manuscripts. In the open-minded Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros , however, the scholar found a like-minded protector who saved him from further harm. Cisneros also promoted humanism institutionally. He founded the University of Alcalá , where in 1508 he set up a trilingual college for Latin, Greek and Hebrew.

In the 16th century, repressive state and church measures drove back humanism. The Inquisition brought the at times strong enthusiasm for Erasmus to a standstill. Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540), one of the most important Spanish humanists and a sharp opponent of scholasticism, therefore preferred to teach abroad.

Even later than in Spain, not until the end of the 15th century, humanism was able to gain a foothold in Portugal. Portuguese students brought humanistic ideas to their homeland from Italy and France. There had already been isolated contacts with Italian humanism in the first half of the 15th century. The Sicilian traveling scholar and poet Cataldus Parisius lived from 1485 as secretary and tutor at the Portuguese royal court in Lisbon, where he introduced humanistic poetry. Estêvão Cavaleiro (Latin Stephanus Eques) wrote a humanistic Latin grammar, which he published in 1493, and boasted of having freed the country from the previously prevailing barbarism. In the years that followed, comparisons between Portuguese and Latin from the point of view of which language should take precedence were popular.

Hungary and Croatia

In Hungary there were individual contacts with Italian humanism early on. The contacts were facilitated by the fact that the Anjou ruling house in the Kingdom of Naples also held the Hungarian throne for a long time in the 14th century, which resulted in close ties with Italy. Under King Sigismund (1387–1437), foreign humanists were already active as diplomats in the Hungarian capital Buda . The Italian poet and educational theorist Pietro Paolo Vergerio († 1444), who lived in Buda for a long time, played a key role in the development of Hungarian humanism . His most important student was Johann Vitez (János Vitéz de Zredna, † 1472) from Croatia , who developed an extensive philological and literary activity and contributed much to the flourishing of Hungarian humanism. Vitez was one of the tutors of King Matthias Corvinus and later became the chancellor of this ruler who ruled from 1458 to 1490, who became the most important promoter of humanism in Hungary. The king surrounded himself with Italian and local humanists and founded the famous Bibliotheca Corviniana , one of the largest libraries of the Renaissance. A nephew of Vitez, Janus Pannonius († 1472), trained in Italy , was a famous humanist poet.

In the 16th century, Johannes Sylvester was one of the most prominent humanists in Hungary. He was one of the current that was oriented towards Erasmus. His works include a Hungarian translation of the New Testament and the Grammatica Hungaro-Latina (Hungarian-Latin grammar) printed in 1539 , the first grammar of the Hungarian language .