German humanism

German humanism is the name of an intellectual movement of the Renaissance that spread in Germany in the 15th and 16th centuries. At first the ideas of the Italian Renaissance humanism and its development of the cultural tradition of antiquity were received. Later there was an independent further development on German soil, which was partly characterized by a strong awareness of one's own cultural identity.

Beginnings in the 15th century

A first change of humanistic ideas north of the Alps had taken place at the large and very internationally oriented church reform councils in Constance (1414–1418) and Basel (1431–1449) , but without any major impact in Germany.

The ideas of humanism were only taken up in a broader form in the German-speaking area from the middle of the 15th century. The core themes of the humanists north of the Alps, such as the renewal or reintroduction of grammar , rhetoric , poetry , moral philosophy , natural philosophy as well as geography and ancient and modern history were based on Italian patterns that were taken up in various areas and adapted to their own circumstances.

The Italian humanist Enea Silvio de 'Piccolomini , who from 1443 to 1455 as a diplomat and secretary to Emperor Frederick III before his election as Pope, played a key role in the introduction of themes and text patterns in Germany . worked in Vienna. He became the leading figure of the first humanistic networks in Central Europe.

In the initial phase, individual German princely courts with their chancelleries (the imperial court of Frederick III and princely courts as in Heidelberg, Eichstätt, Landshut, Stuttgart) formed the first centers of humanism north of the Alps. B. also an imperial city like Augsburg . A significant contribution to the reception of humanism north of the Alps was made by those Germans who had studied law or medicine in Italy and brought ancient and humanistic Latin texts with them and disseminated them in the German-speaking area.

This appropriation of educational content is exemplified in the text collection of Thomas Pirckheimer . In letters and speeches, the early German humanists like Gregor Heimburg or Martin Mair cultivated their new style of communication in front of a larger audience. From the beginning, translations by ancient and Italian authors into German played a major role. B. with Niklas von Wyle or Heinrich Steinhöwel , so that the circle of Germans familiar with ancient fabrics and ideas quickly expanded. Nevertheless, it was still a phenomenon of individual elites for a long time.

Relatively many of the first Germans to come into contact with humanism in Italy returned to exercising influential political functions and were committed to the reform of the Church and secular rule. In addition to royal councilors such as Gregor Heimburg, Martin Mair, Heinrich Stercker or Johannes Cuspinian , this group includes, for example, B. the bishops Johann II. Von Werdenberg in Augsburg, Johann III. von Eych or Wilhelm von Reichenau in Eichstätt.

The Studia humanitatis are taught at German universities

Peter Luder was one of the first Germans to teach Italian humanism as a "wandering humanist" at German universities, thus contributing to its spread. After moving around for years in Italy and establishing relationships there, also being a student of Guarino da Verona , he came to Heidelberg and the university there in 1456 at the invitation of Count Palatine Friedrich I.

The Count Palatine probably became aware of Luder through the University of Padua . Luders start in Heidelberg was spectacular. He presented himself to the university public with a programmatic speech recommending the studia humanitatis . It was the first such speech at a German university. It is considered to be the initial spark of humanism in Germany. The year 1456 , in which Luder gave his speech, is set as the key date for German humanism. This plea for the studia humanitatis was in future Luders parade speech, with which he made his debut at the universities where he taught after his time in Heidelberg. Luder had less success in Erfurt and Leipzig. His student Hartmann Schedel , who published the Schedelsche Weltchronik , became important.

Studia humanitatis were also taught at the University of Basel , which was founded in 1460 . Initially, Peter Anton von Clapis was employed as a teacher in 1464, but he soon went to Heidelberg. In 1468 Luder returned to the German-speaking area after completing a medical doctorate in Padua and succeeded Peter Anton von Clapis in Basel. At the universities in Freiburg (1457), Ingolstadt (1472), Tübingen (1477) and Mainz (1477), which were founded in the last third in Germany, new humanistic subjects were also taught from the outset in addition to traditional subjects, albeit often in subordinate subjects Position.

The first humanists often saw themselves as members of an exclusive group and also cultivated external characteristics, including the use of humanistic typefaces. They often used a humanistic script based on Italian models for their notes . For inscriptions, too, typefaces such as humanist capitalis and Renaissance capitalis were developed based on ancient models and early Italian forms and, due to their difficult implementation, can be seen as a sign of demonstrative familiarity with humanist ideas.

Discourses about the German nation

A popular topic of humanistic speeches was the German praise, the appreciation of virtues considered typically German: loyalty, bravery, steadfastness, piety and simplicity ( simplicitas in the sense of unspoiltness, naturalness). These qualities were initially ascribed to the Germans by Italian scholars who used ancient topoi . From the middle of the 15th century, they were adopted by German university speakers as a self-assessment, and in the following years they shaped the humanistic discourse about a German identity. The humanists emphasized the German possession of the empire ( imperium ) and thus the priority in Europe. They claimed that the nobility was of German origin and that the Germans were morally superior to the Italians and French. German ingenuity was also praised. They liked to refer to the invention of the art of printing, which was considered a German collective achievement. Theoretically, the claim to national superiority encompassed all Germans, but specifically the humanists only focused on the educated elite.

Flowering around 1500

In Germany, the first outstanding representatives of an independent humanism, which emancipated itself from the Italian models, were Rudolf Agricola († 1485) and Konrad Celtis († 1508). Celtis was the first important neo-Latin poet in Germany. He was at the center of an extensive network of contacts and friendships. By founding communities of scholars ( sodalitates ) in a number of cities, Celtis strengthened the cohesion and exchange of humanists. The German King Maximilian I , elected in 1486, promoted the humanist movement for political reasons. In Vienna he founded a humanistic poet college in 1501 with Celtis as director; it belonged to the university and had four teachers (for poetics, rhetoric, mathematics and astronomy). The graduation was not a traditional academic degree, but a poet's coronation.

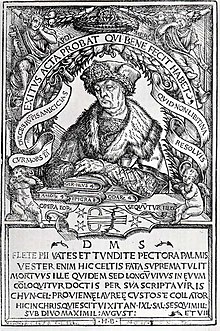

Speakers of the humanistic movement in Germany around 1500 included the jurists Konrad Peutinger (1465–1547) and Willibald Pirckheimer (1470–1530), the historians Johannes Aventinus (1477–1534) and Jakob Wimpheling (1450–1528), the philosopher, Graecist and Hebraist Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522), the publicist Ulrich von Hutten (1488–1523) and the historian and philologist Beatus Rhenanus (1485–1547). Ulrich von Hutten was the most prominent representative of militant political humanism; he combined humanistic scholarship with patriotic goals and a cultural-political nationalism. In the next generation, the Graecist and educational reformer Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560) held a prominent position; he was called Praeceptor Germaniae ("Germany's teacher"). As a science organizer, he had a lasting impact on the organization of schools and universities in the Protestant area; as the author of school and study books, he was pioneering in didactics. He influenced Martin Luther in terms of humanistic values.

Humanists and the fine arts

Like many humanists in Italy, many German humanists were also interested in the resurgence of the visual arts and sometimes tried their hand at drawing. Celtis work z. B. together with Albrecht Dürer . The joint project of Germania illustrata , a geographical, historiographical and ethnological description of Germany, remained unfinished, but the preliminary studies had an intense aftereffect. Humanistic impulses also shaped the new landscape painting by Albrecht Altdorfer . Lucas Cranach's extensive painter's workshop was also closely linked to humanistic intellectuals.

Bible humanism

The humanistic striving for direct access to the ancient classics in the original language ( ad fontes ) also included the philological, text-critical engagement with the Bible and ancient Christian and Jewish literature. Several German theologians became Hebraists . Some exponents of Bible humanism such as Johannes Reuchlin , Sebastian Münster and Johann Böschenstein wrote treatises on Hebrew accents and spelling. Johannes Reuchlin, who among other things learned the Greek and Hebrew languages from Manuel Chrysoloras in Constantinople , contributed significantly to the spread of knowledge of Hebrew among German theologians. In the dispute over the dark man's letters , the German humanists argued with their conservative scholastic opponents.

Reuchlin's most important student was Philipp Melanchthon . Melanchthon and other evangelical humanists like Johannes Bugenhagen , Luther's confessor in Wittenberg , also used humanism for the purposes of the Reformation. The Dutch humanist Erasmus von Rotterdam , who was also influential in Germany, pursued a different goal . He tried to counter the increasing denominational polarization through humanistic ideals.

Other well-known German humanists

Other well-known German humanists include Sigismund Meisterlin , Hartmann Schedel , Heinrich Bebel , Sebastian Brant , Hermann von dem Busche , Johannes Cuspinian , Petrus Divaeus , Sebastian Franck , Hieronymus Gebwiler , Konrad Heresbach , Eobanus Hessus , Albert Krantz , Sebastian Münster , Hermann von Neuenahr , Johannes Nauclerus , Konrad Peutinger , Willibald Pirckheimer , Jodocus Gallus , Johannes Rivius , Mutianus Rufus , Georg Sabinus , Johann Sleidan , Jakob Spiegel and Jakob Wimpheling .

Source collections

- Wilhelm Kühlmann u. a. (Ed.): The German humanists. Documents on the transmission of ancient and medieval literature in the early modern period . Brepols, Turnhout 2005 ff.

- Department 1: The Electoral Palatinate

- Volume I / 1: Marquard Freher , 2005, ISBN 2-503-52017-0

- Volume I / 2: Janus Gruter , 2005, ISBN 2-503-52017-0

- Volume 2: David Pareus, Johann Philipp Pareus and Daniel Pareus , 2010, ISBN 978-2-503-53238-7

- Volume 3: Jacob Micyllus, Johannes Posthius, Johannes Opsopoeus and Abraham Scultetus , 2011, ISBN 978-2-503-53330-8 .

- Department 1: The Electoral Palatinate

- Harry C. Schnur (Ed.): Latin poems by German humanists . 2nd edition, Reclam, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-15-008739-2 (Latin texts with German translation).

- Winfried Trillitzsch: The German Renaissance Humanism. Röderberg, Frankfurt am Main 1981 (German translations of humanistic texts).

literature

- Ulrich Muhlack: Renaissance and Humanism (= Encyclopedia of German History 93). Berlin, Boston 2017.

-

Franz Josef Worstbrock (Ed.): German Humanism 1480–1520. Author Lexicon . 3 vols. De Gruyter, Berlin 2008 - 2015.

- Vol. 1: A - K (2008)

- Vol. 2: L - Z (2013)

- Vol. 3: Supplements, Addenda and Corrigenda, Register (2015)

-

Early modern times in Germany 1520–1620. Literary scholarly author's lexicon (VL 16) . Since 2011, a supplementary edition of the author's lexicon has been published under the leadership of an editorship led by Friedrich Vollhardt .

- Vol. 1: Aal, Johannes - Chytraeus, Nathan (2011)

- Vol. 2: Clajus, Johannes - Gigas, Johannes (2012)

- Vol. 3: Glarean, Heinrich - Krüger, Bartholomäus (2014)

- Vol. 4: Krüginger, Johannes - Osse, Melchior von (2015)

- Franz Fuchs (Ed.): Humanism in the German Southwest. Files of the together with the association for art and antiquity in Ulm and Oberschwaben and the city archive house of the city history Ulm on 25./26. October 2013 organized symposions in the Schwörhaus Ulm . Wiesbaden 2015.

- Johannes Helmrath: Ways of Humanism. Studies on techniques and diffusion of the passion for antiquity in the 15th century Tübingen 2013. Sections of the book via Google Books, u. a. Humanism in Germany

- Maximilian Schuh: Appropriations of humanism, institutional and individual practices at the University of Ingolstadt in the 15th century . Suffering a.] 2013.

- Johannes Helmrath et al. (Ed.): Historiography of humanism: literary procedures, social practice, historical spaces . Berlin 2012.

- Thomas Maissen ; Gerrit Walther (Ed.): Functions of Humanism. Studies on the Use of the New in Humanistic Culture , 2006.

- Harald Müller: Habit and Habit . Monks and humanists in dialogue. Tuebingen 2006.

- Johannes Helmrath et al. (Ed.): Diffusion of humanism: studies on the national historiography of European humanists . Göttingen 2002.

- Franz Brendl, et al. (Ed.): German regional historiography under the sign of humanism . Stuttgart 2001. Excerpts from the book via Google Books

- Sven Limbeck: Theory and Practice of Translation in German Humanism. Albrecht von Eyb's translation of the “Philogenia” by Ugolino Pisani . Freiburg (Breisgau) Univ. Diss. 2000.

- Hans Rupprich and Hedwig Heger: The German literature from the late Middle Ages to the Baroque. The outgoing Middle Ages, Humanism and Renaissance 1370 - 1520. (= History of German Literature Vol. 4/1). Munich 1994.

- Wolfgang Reinhard (Hrsg.): Humanism in the education system of the 15th and 16th centuries . Verlag Chemie, Weinheim 1984, ISBN 3-527-17012-X

- Noel L. Brann: Humanism in Germany . In: Albert Rabil (Ed.): Renaissance Humanism. Foundations, Forms, and Legacy , Volume 2: Humanism beyond Italy , University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 1988, ISBN 0-8122-8064-4 , pp. 123-155

- Erich Meuthen : Character and tendencies of German humanism . In: Heinz Angermeier (Hrsg.): Secular aspects of the Reformation time . Oldenbourg, Munich and Vienna 1983, ISBN 3-486-51841-0 , pp. 217-276

- Dieter Wuttke: Dürer and Celtis. On the significance of the year 1500 for German humanism . In: Humanism and Reformation as Cultural Forces in German History, 1981, pp. 121–150.

- Heinz Otto Burger: Renaissance, Humanism, Reformation. German literature in a European context . Bad Homburg vdH 1969.

- Hans Rupprich: The early days of humanism and the Renaissance in Germany , Leipzig 1938.

- Paul Joachimsohn: Early Humanism in Swabia . In: Württembergische Vierteljahrshefte für Landesgeschichte 5 (1896), pp. 63–126, pp. 257–291.

- Marco Heiles: Topography of German humanism 1470-1550 . An approach [1]

Web links

- Paul Joachimsen: Humanism and the development of the German spirit. In: Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte, 8 (1930), pp. 419-480.

- Dieter Mertens: German Renaissance Humanism. In: Humanism in Europe. Heidelberg 1998, pp. 187-210.

- Article "Humanism" on the platform Lernhelfer

- Marco Heiles: Topography of German humanism 1470–1550 (last accessed on April 6, 2017)

Individual evidence

- ↑ On the conceptual history: Ulrich Muhlack: Renaissance und Humanismus (= Encyclopedia of German History 93). Berlin, Boston 2017.

- ^ Jana Lucas: Europe in Basel. The Council of Basel 1431–1449 as a laboratory for art . Basel 2017.

- ↑ For details see Johannes Helmrath: Vestigia Aeneae imitari. Enea Silvio Piccolomini as the "apostle" of humanism. Forms and ways of its diffusion . In: Johannes Helmrath et al. (Ed.): Diffusion des Humanismus , Göttingen 2002, pp. 99–141.

- ↑ Agostino Sottili : Humanism and University Attendance . The effect of Italian universities on the Studia Humanitatis north of the Alps. = Renaissance humanism and university studies. Italian universities and their influence on the Studia Humanitatis in Northern Europe (= 'Education and society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance 26). Brill, Leiden et al. 2006.

- ↑ Georg Strack: Thomas Pirckheimer (1418–1473) , Husum 2010, pp. 188–237.

- ↑ Martin Steinmann: The humanistic script and the beginnings of humanism in Basel. In: Archiv für Diplomatik 22 (1976), pp. 376–437.

- ↑ Caspar Hirschi : Competition of Nations , Göttingen 2005, pp. 253–379; Georg Strack: De Germania parcissime locuti sunt ... The German university nation and the “praise of the Germans” in the late Middle Ages . In: Gerhard Krieger (Ed.): Relatives, Friendship, Brotherhood , Berlin 2009, pp. 472–490.

- ↑ See also Franz Machilek: Konrad Celtis and the learned modalities , especially in East Central Europe . In: Winfried Eberhard, Alfred A. Strnad (eds.): Humanism and Renaissance in East Central Europe before the Reformation , Cologne 1996, pp. 137–155; Christine Treml: Humanist Community Education, Hildesheim 1989, pp. 46–77.

- ^ Michael Baxandall: Rudolf Agricola and the Visual Arts . In: Intuition and Art History. Festschrift for Hanns Swarzenski on his 70th birthday, ed. v. Peter Bloch and Tilmann Buddensieg u. a. Berlin 1973, pp. 409-418.

- ↑ Gernot Michael Müller: The "Germania generalis" of Conrad Celtis. Studies with edition, translation and commentary . Tübingen 2001. Jörg Robert: Dürer, Celtis and the birth of landscape painting from the spirit of "Germania illustrata" . In: Daniel Hess and Thomas Eser (eds.), The early Dürer. Exhibition in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg 2012, 65–77.

- ↑ Christopher S. Wood: Albrecht Altdorfer and the origins of landscape . Chicago 1993.

- ↑ Edgar Bierende: Lucas Cranach the Elder . Ä. and German humanism. Panel painting in the context of rhetoric, chronicles and prince mirrors . Munich, Berlin 2002.

- ↑ http://www.mediaevum.de/forschen/projekt_anz.php?id=150 and http://www.ndl1.germanistik.uni-muenchen.de/forschung/drittmittel/verfasserlexikon/index.html