Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio ( [d͡ʒoˈvanːi boˈkːat͡ʃːo] ; born June 16, 1313 in Certaldo or Florence , † December 21, 1375 in Certaldo) was an Italian writer , democrat, poet and important exponent of Renaissance humanism . His masterpiece, the Decameron , portrayed the multifaceted society of the 14th century with a hitherto unknown realism and wit and made him the founder of the prosaic narrative tradition in Europe.

Life

The exact circumstances of his birth are not certain. Boccaccio was born in 1313, probably in Florence or in the nearby mountain village of Certaldo , as the illegitimate son of the merchant Boccaccio di Chellino. His mother died shortly after giving birth. Later the legend, quoted in many sources and promoted by himself and still unproven today, came up that he was born in Paris , a result of a relationship between his father and a French nobleman named Giovanna.

As a child he lived in Florence in his father's house, who worked for the Compagnia dei Bardi , a banking company. As a youth - around fourteen years old - he was sent to Naples to work in a branch of the Compagnia dei Bardi to practice the trade of a businessman.

The years spent in Naples (until 1340) had a major impact on Boccaccio's personal and intellectual development. Instead of engaging in the study of commercial activity or canon law, as the father had wanted, he devoted himself to his passion for literature. He gained access to the Neapolitan court of Robert of Anjou , where he got to know the elegant, courtly lifestyle, associated with intellectuals and self-taught a wide range of education.

It was also during this period that he wrote his first works in verse and prose, in which Boccaccio experimented with different genres and styles. In keeping with the taste of the time, he designed the recurring image of an ideal lover whom he called Fiammetta and whose real model is probably a Neapolitan noblewoman named Maria d'Aquino .

In 1340 he returned to Florence. Due to financial difficulties, he entered the civil service and held several offices. Between 1345 and 1346 he went to the court of Ostasio da Polenta in Ravenna , while the next year he was in the service of Francesco Ordelaffi in Forlì . The bourgeois-urban environment, very different from court life, was an important source of inspiration for his fruitful literary activity in that decade that culminated in the Decameron , written in the years after the plague epidemic that struck Italy in 1348.

His masterpiece was certainly already completed when he first met Francesco Petrarca in the autumn of 1350 . Boccaccio made a deep friendship with him. Both had a common admiration for classical authors, as their correspondence shows, in which they exchanged literary experiences.

Now that his fame had grown, the Florentine city council entrusted him with various diplomatic assignments that took him on many journeys.

During these years Boccaccio devoted himself - also influenced by his friend Petrarca - to his study of classical texts. Around 1355 he got free access to the library of Montecassino , where many masterpieces from antiquity had survived. Boccaccio even copied some of the precious codices by hand.

Soon a circle of intellectuals emerged around Petrarch and Boccaccio, who rediscovered some important classical works, including the Annals of Tacitus and the Metamorphoses of Apuleius .

After Boccaccio began studying Greek around 1360, he managed to have the first chair set up in Florence. This was checked in Leontius Pilatus awarded the Boccaccio beyond the translation of the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer entrusted into Latin. These works could therefore be read by a much wider audience.

His interest in antiquity also influenced literary production towards the end of his life. In the later years of his life he wrote less narrative texts held in Volgare , but more works in Latin that dealt with encyclopedic or philological topics.

This change may also be due to a religious crisis in Boccaccio's life. This is said to have been so profound that Boccaccio even wanted to destroy some of his works that he now believed to be immoral. However, he could be held back by Petrarch. This representation is called into question by the fact that he was still making copies of his Decameron by hand around 1370 . He had already entered the minor clergy in 1360, although probably due to financial hardship. Finally, in 1362 he met the Carthusian monk Gioachino Cianni from Siena , who converted Boccaccio to a "pious life".

In 1373 he, who had already sparked the cult of Dante Alighieri with his biography of Dante twenty years earlier, was instructed by the city of Florence to read, explain and comment on the Divina Commedia publicly . In 1374, however, his health deteriorated due to a probable hydropsia and so he had to stop this activity.

He eventually settled in Certaldo and worked on some works until his death on December 21, 1375.

Others

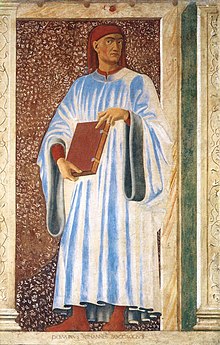

In 2013, on the occasion of his 700th birthday, a 2 euro commemorative coin with his portrait in three-quarter profile was released . This is taken from the fresco by Andrea del Castagno .

Works

- The Italian works

- The Neapolitan phase

- La caccia di Diana 1334, short epic in 18 songs

- Il Filostrato 1335, epic in stamps (ottava rima)

- Il Filocolo 1336–1339, novel in prose

- Teseida 1340–1341 (completed in Florence), epic in punches (ottava rima)

- Rime , a collection of poems that Boccaccio wrote throughout his life; never summarized by himself in one work

- The years 1340-1350

- Ninfale d'Ameto 1341–1342, pastoral novel in verse and prose

- L'amorosa visione 1342–1344, epic in terzines, imitates Dante's Divina Commedia

- Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta 1343–1344, novel in prose

- Ninfale fiesolano 1344–1346, epic in punches (ottava rima)

- The main work

- Il Decamerone 1348–1353, collection of short stories

- The late work

- Il Corbaccio 1354, satire in prose

- Trattatello in laude di Dante 1351-1373, biography of Dante Alighieri

- Esposizione sopra la Commedia di Dante 1373-1374, tradition of his public lectures and commentaries on the Divina Commedia

- The Latin works

- Bucolicum carmen 1349–1367, sixteen eclogues

- Genealogia deorum gentilium 1350–1367, collection of mythological stories from antiquity in 15 books

- De montibus, silvis, fontibus, lacubus, fluminibus, stagnis, seu paludibus et de nominibus maris liber 1355–1375, an extensive catalog of geographical objects that appear in classical literature

- De casibus virorum illustrium 1356–1373, collection of episodes from the lives of famous people who suffered a bad fate

- De mulieribus claris 1361–1362, collection of moralizing biographies of famous women of antiquity and the Middle Ages

Text editions and translations

- Brigitte Hege (ed.): Boccaccio's apology of pagan poetry in the Genealogie deorum gentilium. Book XIV. Text, translation, commentary, and treatise. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-86057-183-4

- Virginia Brown (Ed.): Giovanni Boccaccio: Famous Women. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2001, ISBN 0-674-00347-0 (Latin text and English translation)

- Jon Solomon (Ed.): Giovanni Boccaccio: Genealogy of the Pagan Gods. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2011 ff. (Latin text and English translation)

- Volume 1: Books I – V , 2011, ISBN 978-0-674-05710-4

literature

- Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer : Boccaccio and the beginning of the novella. Structures of the short narrative on the threshold between the Middle Ages and modern times. Munich 1969.

- Joachim Heinzle : Boccaccio and the tradition of the novella. For structural analysis and genre determination of small forms between the Middle Ages and modern times. In: Wolfram-Studien 5 (1979), pp. 41-62.

- Hans-Joachim Ziegeler : Boccaccio, Chaucer, Mären, short stories: "The Tale of the Cradle". In: Klaus Grubmüller u. a. (Ed.): Smaller narrative forms in the Middle Ages. Paderborn Colloquium 1987. Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 1988, pp. 9–32.

- Winfried Wehle : Death, Life and Art: Boccaccio's Decameron or the Triumph of Language. In: Arno Borst (Ed.): Death in the Middle Ages. Konstanz 1993, pp. 221-260. Online (PDF; 250 kB).

- Winfried Wehle : In the purgatory of life: Boccaccio's project of a narrative anthropology. In: Achim Aurnhammer, Rainer Stillers (ed.): Giovanni Boccaccio in Europe: Studies on its reception in the late Middle Ages and early modern times. Wiesbaden 2014, pp. 19–45. Online (PDF; 3 MB).

Web links

- Literature by and about Giovanni Boccaccio in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Giovanni Boccaccio in the German Digital Library

- Works by Giovanni Boccaccio at Zeno.org .

- Works by Giovanni Boccaccio in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Works by Giovanni Boccaccio : text, concordances, word lists and statistics

- Copy in humanistic cursive by Giovanni Cardello da Imola : Giovanni Boccaccio: Elegy of Madonna Fiammetta Italy 1467 in the digital offer from Cologny, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cod.Bodmer 39

- Le livre de Jehan Bocace des cas des nobles hommes et femmes Digitized from a 15th century French manuscript BSB Cod.gall. 6th

Individual evidence

- ↑ Natalino Sapegno, Giovanni Boccaccio, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 10, Roma, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- ↑ a b Timeline and bibliographical information in: Giovanni Boccaccio: Das Dekameron , Munich 1981, ISBN 3-442-07599-8 , p. 860 f.

- ↑ website of the ECB . The portrait is on display in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Boccaccio, Giovanni |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 16, 1313 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Certaldo or Florence |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 21, 1375 |

| Place of death | Certaldo |