Naples

| Napoli Naples |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Country | Italy | |

| region | Campania | |

| Metropolitan city | Naples (NA) | |

| Coordinates | 40 ° 50 ′ N , 14 ° 15 ′ E | |

| height | 17 m slm | |

| surface | 117.27 km² | |

| Residents | 962,589 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density | 8,208 inhabitants / km² | |

| Post Code | 80100 | |

| prefix | 081 | |

| ISTAT number | 063049 | |

| Popular name | Napoletani | |

| Patron saint | San Gennaro | |

| Website | www.comune.napoli.it | |

Satellite image with city limits; Vesuvius to the southeast , the Gulf of Naples with the islands of Ischia , Procida and Capri , and the Phlegraean Fields to the west |

||

| Historic center of Naples | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (ii) (iv) |

| Surface: | 1,021 ha |

| Reference No .: | 726 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1995 (session 19) |

Naples ( Italian Napoli , Neapolitan Napule , ancient Greek: Νεάπολις "new city") is the third largest city in Italy after Rome and Milan with almost one million inhabitants . The capital of the Campania region and the metropolitan city of Naples is an economic and cultural center of southern Italy . The metropolitan region has up to 4.4 million inhabitants. Many Neapolitans speak Neapolitan, which differs greatly from standard Italian .

The original Greek settlement was named Neapolis ("New Town"). Later it came under Roman rule. From the late Middle Ages to the 18th century, Naples was one of the largest cities in Europe. Its political history is largely shaped by foreign rule, and it was also the capital of southern Italian empires.

There are numerous historical buildings and cultural monuments in the inner city districts; In 1995 the entire old town was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The heterogeneous cityscape offers suburbs with huge residential complexes and wide areas in contrast to the narrow and heavily frequented streets of the old town. While the wealth is concentrated in the districts west of the center, in the inner districts and the old town you can sometimes find overpopulation and economically backward areas. The social situation of the suburbs is different, some are working-class neighborhoods, some are satellite cities that have emerged in the course of social housing, but others are also rural areas. A major problem is the above-average unemployment.

Surname

The Italian name of the city is Napoli [ˈnaːpoli] , but the inhabitants also use the Neapolitan name Napule . The name has its origin in the time of the foundation by the Greeks . The ancient Greek νέα πόλις ( néa pólis ) means "new city". Since the nearby settlement Parthenope already existed, it was called around 500 BC. A second foundation of Neapolis. Both Parthenope and Neapolis were in the center of what is now the city. The name Parthenope is still used as a literary paraphrase for Naples.

National nature

climate

The city's weather is determined by the Mediterranean climate with mild and rainy winters as well as hot and dry summers, with the peaks of summer heat being moderated by the location by the sea.

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Naples

Source: wetterkontor.de

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

relief

Naples is located on a 30 km long bay , the Gulf of Naples . On this gulf there is a 13 km long caldera , the Phlegraean Fields (Campi Flegrei) . They are formed by about 40 small and large volcanic craters , the most famous of which is the solfatara . The so-called Monte Nuovo (New Mountain) also made it famous . It got its name because it was formed in just a few days, when the volcano only erupted in 1538.

On the other side of Naples, also on the Gulf, is Mount Vesuvius , one of the most famous volcanoes in the world. It is around 17,000 years old, 1,281 m high and is considered active. Because of its proximity to urban areas, it is considered dangerous. The last time it broke out was in March 1944, when American troops were in Naples during World War II . Soldiers and camera teams took numerous photos and films of the outbreaks.

Cultural landscape

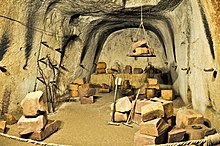

Volcanic rock as a building material and the underground of Naples

As in other volcanic areas, the building material that dominated Naples for centuries was lava rock, which is located in several layers under the city and comes from volcanic eruptions of the Campi Flegrei and Vesuvius . It has been mined in the area (Poggioreale, Campi Flegrei) and later in the urban area since antiquity, both in open pit and in tunnels. In the urban area are the natural gorges, mining tunnels and catacombs in the hill of Capodimonte, others in Vomero and Pizzofalcone, but volcanic rocks were also broken up directly below the construction sites of the city and transported to the surface in block form. For this purpose, the upper layers of the earth were first removed and then a vertical tunnel was drilled into the rock, which was also expanded in width after about 5 m. This saved the transport route to the construction site. Over time, this practice created an underground system of cavities, which since ancient times has been expanded into a system of canals connected to the surface by wells. This supplied Naples with drinking water until 1885 (construction of a modern water supply for reasons of hygiene) and served as an air raid shelter during the bombing of Naples in World War II. The tunnels were also used as housing by the poorest layers of the world when water stopped flowing in 1885. The undercutting of the city has resulted in static problems to this day: "With the millions and millions of broken tuff blocks in the underground of Naples, it is no longer surprising that the surface of the earth occasionally gave way and devoured entire blocks of houses." As early as 1781, Ferdinand IV within the city walls. Since there are still widely branching passages, caves, cisterns and aqueducts like the Acquedotto del Carmignano , one speaks of a second "underground Naples" (Napoli sotteranea) .

The basic building material that shaped Naples and was used for the construction of fortresses (Castel dell'Ovo, Castel Sant'Elmo) was the yellow Neapolitan tuff . Above the tufa layers, a few meters below the surface, lie meter-thick layers of volcanic ash, the pozzolana . Since tufa does not hold up well and is not very resistant, it has been covered with a plaster made from pozzolana, lime and lapilli since ancient times . As soon as it has dried, this plaster reaches a rock-solid and waterproof consistency. Another volcanic derivative can be found under the tuff, the gray peperin . Tufa is easy to work with and can be broken with simple tools, and the resulting blocks are also lightweight. Peperin is (like the trachyte, which is also used ) a harder rock, from which stairs and load-bearing elements of building construction were made. The combination of the solid peperin and the light tuff made it possible to build houses with up to seven floors early on, as a report from 1634 shows. So the older simple houses, but also palaces and boundary walls consist mainly of lava rock to this day. It was not until the industrial age that it was replaced by artificial building materials such as iron, reinforced concrete, steel and glass.

You can visit the underground in three different places. First, there is the Borbonico Tunnel , an underground escape tunnel that connects the Royal Palace in Piazza del Plebiscito with Via Morelli . Secondly, there are guided tours that start in Piazza Trieste e Trento , and the Napoli Sotterranea Association offers another opportunity .

city

Until 1925 the urban area covered only about 52 km². On November 15, 1925, it was enlarged by the municipalities of San Pietro a Patierno , Barra , Ponticelli and San Giovanni a Teduccio . By a law of June 3, 1926, Secondigliano , Chiaiano , Pianura and Soccavo were added to the urban area. These municipalities with a total of 116,639 inhabitants doubled the area of Naples to 117 km². The youngest district is Scampia , it was formed in 1985 from areas of several districts.

Politically, the total of 30 districts ( quartieri ) of the city are grouped into ten administrative districts ( municipalità ):

| Municipalità 1 | 1. San Ferdinando , 2. Chiaia and 15. Posillipo | |

| Municipalità 2 | 3. San Giuseppe , 4. Montecalvario , 5. Avvocata , 10th Mercato , 11th Pendino and 12th Porto | |

| Municipalità 3 | 6. Stella and 7. San Carlo all'Arena | |

| Municipalità 4 | 8. Vicaria , 9. San Lorenzo , 16. Poggioreale and 17. Zona Industriale | |

| Municipalità 5 | 13. Vomero and 14. Arenella | |

| Municipalità 6 | 28. Ponticelli , 29. Barra and 30. San Giovanni a Teduccio | |

| Municipalità 7 | 24. Miano , 25. Secondigliano and 27. San Pietro a Patierno | |

| Municipalità 8 | 22. Chiaiano , 23. Piscinola and 26. Scampia | |

| Municipalità 9 | 20th Soccavo and 21st Pianura | |

| Municipalità 10 | 18th Bagnoli and 19th Fuorigrotta |

There are numerous smaller quarters ( rioni ) within the city districts ; Examples are the Quartieri Spagnoli and Sanità .

The metropolitan region consists of the city of Naples and numerous surrounding independent municipalities. The population density of the metropolitan region is very high by European standards. The size and thus the number of inhabitants are defined differently by different institutions. One can assume about 3.1 to 4.4 million inhabitants (the region of Campania has 5.8 million inhabitants, the city of Naples about 1 million).

Outskirts

In addition to Vesuvius, the Roman cities of Herculaneum and, above all, Pompeii (over 2 million visitors a year) , which were buried by lava and ash in 79 and thus exceptionally well preserved, have become centers of tourism.

About an hour's drive southeast of Naples is the Amalfi Coast , which was included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997 . The main source of income for this historical cultural landscape is tourism. Amalfi , Praiano and Positano are among the most important places, all of which are on the steep coast .

West of Naples there are, in addition to the overgrown volcanic landscapes of the Campi Flegrei, numerous villages and towns with beaches as well as excavations from Greek and Roman times. The most important are Capua , Cumae , Pozzuoli and Bacoli .

There are three islands in the Gulf of Naples, the most famous of which are Capri and Ischia , with numerous thermal baths , hotels and beaches. The smallest and least touristically developed island is Procida .

20 kilometers north of Naples is one of the largest castles in Europe, the Palace of Caserta . The royal residence was built in the 18th century and is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Portici royal palace in the west of Naples also dates from the same period .

Population and society

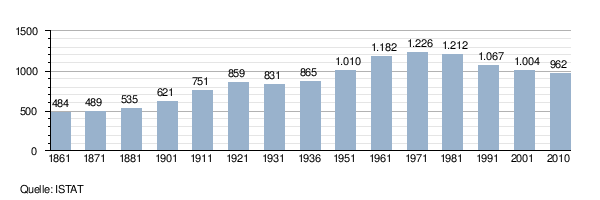

Population development

After Rome with 2.8 million and Milan with 1.3 million inhabitants, Naples is the third largest city in Italy and before Palermo (0.7 million inhabitants) the largest city in southern Italy. The population density in 2001 was 8,566 inhabitants per square kilometer, compared to only 6,900 in Milan, 1,982 in Rome and 4,322 in Palermo.

In 2001 around 17% of Neapolitans, but only 14% of Italians, were younger than 15 years old.

Population up to 1748 (in thousands)

Development of the population (in thousands)

Social spatial structure

According to the Comune di Napoli , Naples is divided into two parts according to socio-economic criteria. The social conditions under which the residents of the city center live differ significantly from those of the residents of the suburban periphery. But there are also big differences within the center. The core of the old town in the 9th district of San Lorenzo and many of the adjacent areas are densely populated residential areas of poorer classes. In the 3rd district of San Giuseppe there are administrative buildings such as the Naples City Hall and numerous bank buildings. Popular residential areas of richer population groups, upscale shopping streets and consulate quarters are located directly west of the old town. Both the 13th district Vomero and the 2nd district Chiaia are geographically delimited and only connected to the old town by a few streets; Vomero is located on the Vomero hill of the same name , between Chiaia and the old town there are elevations ending with the Pizzofalcone . In the 15th district of Posillipo , located along the sea and on the hill of the same name , you will find numerous luxury villas and expensive residential areas.

Today's peripheral districts were not politically incorporated into the city until the 20th century. For a long time, these areas were characterized by rural areas, and today's residential areas have only emerged since the 1960s. The eastern periphery is still considered to be a workers-dominated area, while the north around the districts of Secondigliano (25) and Scampia (26) is hardest hit by social problems such as unemployment, drug addiction and crime. The decisive factor was a law passed by the Italian state in 1962 ( legge 167 ). With him a plan was decided for the most economical construction of large residential areas in the cities of all of Italy ( social housing , dormitory ). The areas to be selected for this were called zone 167 . They were mostly located in the periphery , i.e. outside the city centers, and should be equipped with an independent infrastructure. For example, Scampia was created under this law.

The highest population density is reached in the 9th district of San Lorenzo in the old town with 33,070 inhabitants per square kilometer (2009), the lowest in the rural 22nd district of Chiaiano with 2,331.

For centuries, Naples has been considered a city with great social differences. A well-known group within the Neapolitan lower class were the Lazzaroni from the 17th to the 19th centuries . Today there are numerous illegal immigrants in the city, in addition there are quite a few in the peripheral parts of the city and another unofficial Roma settlement directly at the port without modern infrastructure and with poor hygienic conditions.

There are two large prisons in the city. The prison Poggioreale ( Casa Circondariale di Napoli Poggioreale ) was not only the temporary residence of numerous well-known camera artists, but also the location of well-known films and is a well-known place in the city. It is currently overcrowded with over 2,000 prisoners. The second large detention center (Centro Penitenziario di Secondigliano) is located in the problematic Scampia district and had 1,136 inmates in 2009.

Organized crime

It is believed that several thousand Neapolitans belong to the Neapolitan Mafia organization Camorra . The activities of the now internationally operating Camorra are hidden, so that outsiders rarely come into contact with it. The ubiquitous trade in smuggled or counterfeit products in some parts of the city is an exception. The main sources of income for the Camorra are smuggling, black market trafficking, drug trafficking, contract agreements, illegal waste disposal and extortion; Today, however, legal businesses financed with illegal income also play an important role. The Camorra is particularly popular because of the high unemployment rate, especially among young people. It offers them (statistically unrecorded) work, in general the shadow economy is a significant economic power of the city. The Camorra critic Roberto Saviano achieved popularity throughout Italy . The major sponsor of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata (NCO) of the 1970s and 1980s was the day in the high security prison Terni detained Raffaele Cutolo . One of the most influential clans of recent times was and is the Di Lauro clan under Paolo Di Lauro , who was arrested in 2005 .

In the past, various Camorra clans have been involved in gang wars with numerous fatalities, mainly within the Mafia itself. The last major gang war with around 70 deaths was the faida di Scampia (feud of Scampia) in 2004 and 2005 . In 2009, 104 murders (Italy: 586) were committed in the entire region of Campania (5.8 million inhabitants), 49 of which were attributable to the Mafia (Italy: 90) Naples and the surrounding area - not least because of the Camorra, who earns from it - problems with the disposal of garbage and hazardous waste as well as the probably resulting contamination of the soil.

politics

In May 2011, the former public prosecutor and opponent of the Mafia, Luigi de Magistris , ran for local elections as the top candidate of a left-liberal party alliance, led by the Italia dei Valori party . He surprisingly relegated Mario Morcone, the representative of the Partito Democratico of Mayor Rosa Russo Iervolino (who was no longer up for election), to third place and entered the runoff election for mayor against Giovanni Lettieri, the candidate of the center-right Alliance. One of the main topics in the election campaign was the garbage problem, for which the citizens no longer believed the parties that had previously ruled the city to solve. De Magistris prevailed with 65 to 35% votes. On July 18, 2011, he then resigned his mandate as a MEP . His electoral alliance also has a majority in the municipal council with 29 out of 45 seats.

Town twinning

Naples has so-called friendship and cooperation agreements with the following cities.

economy

The cityscape is characterized by traditional small business with numerous shops, traders and handicraft businesses. In 2005, the Neapolitan Chamber of Commerce registered 264,956 companies in the province of Naples. Of these companies, 52 had more than 200 employees and 12 more than 500, while 54% of the companies had fewer than 20 employees. The company density is correspondingly high; in 2010 there were 108 companies per 1000 inhabitants.

Service companies in the real estate, administration, financial services and trade sectors represent an economic factor; the manufacturing sector is rather weak. The formerly important steelworks in the Bagnoli district has been closed since 1990 and is now an industrial ruin; the port of Naples continues to be of international importance for both freight and passenger traffic.

Overall, Naples’s economic strength per capita is rather weak. In a national comparison, the province of Naples was only 92nd in 2005 out of a total of 103 provinces nationwide. Youth unemployment is a particular problem. For 15 to 24 year olds in 2010 it was 42.7%, well above the Italian average of 27.8%. Thanks to its size, Naples is one of the most important economic centers in Italy.

employment

Employment in the province is distributed among the individual sectors as follows:

- 30.7% public services and administration

- 18.0% production

- 14.0% trade

- 9.5% construction

- 8.2% transportation

- 7.4% banking, finance and real estate

- 5.1% agriculture

- 3.7% hotel business

- 3.4% other

tourism

In 1992 around 550,000 people arrived in Neapolitan hotels and hostels, in 2009 it was around 800,000. The high point was in 2007 with around 900,000 guests.

Others

In 2009, 560,525 tons of waste were collected in Naples (2000: 561,929 tons), of which 105,935 tons was separate waste (2000: 7,445 tons). For every Neapolitan there is 582 kg of waste per year (2000: 561 kg).

Publicly accessible green spaces make up only 5.23 of the city's 117.27 km², of which 1.41 km² on the rural Chiaiano district and 1.46 km² on the San Carlo all'Arena district, in which the city's largest park is located , fall.

traffic

Long-distance transport

Naples has excellent long-distance transport connections: the city is surrounded by a dense network of motorways, connected to the Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane rail network, has a large seaport and the Aeroporto di Napoli-Capodichino , an international airport .

Highway

A toll must be paid on all motorways (see Tolls in Italy ). Naples has direct access to the motorways via a dense network of feeders. The A1 / E 45, the Autostrada del Sole ("Motorway of the Sun"), leads in a north-north-west direction via Rome and Florence to Milan and the other economic centers of Northern Italy. Its extension in a south-southeast direction runs as A3 / E 45 (from Salerno as A2 / E 45 ) to Reggio Calabria . To the east, finally, to the Adriatic coast , one arrives via the A16 , the Autostrade dei due Mari ("Motorway of the Two Seas"). There are also some connections via trunk roads, the strade statali (“state roads”).

Airport

With the airport Capodichino , the most important airport in southern Italy, Naples is connected to the international air traffic routes. The major Italian aviation hubs Rome and Milan as well as other Italian airports are served by flights from Naples - sometimes several times a day. In addition, there are regular intra-European and, for some years now, intercontinental connections.

railroad

With several train stations, Naples is connected to the rail network of Ferrovie dello Stato , the Italian railways. The most important station for long-distance traffic is the Stazione Napoli Centrale in one of the city centers, near Piazza Garibaldi. Here there is a connection to the large north-south long-distance route along the Tyrrhenian coast , which comes from Reggio di Calabria via Naples, Rome and Florence to the metropolises of the Po Valley . Another long-distance route crosses the Apennine peninsula via Benevento and Foggia and connects to the Adriatic IC and ETR lines.

port

In addition to its importance for regional passenger and freight traffic, the port of Naples is one of Italy's larger seaports for international traffic. In addition to its function as a port for container and conventional freight, it also covers international passenger traffic via a large cruise terminal. Regular ferry connections also lead to Tunisia, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily and the Aeolian Islands . Long-distance passenger traffic runs through the Stazione Marittima di Napoli .

Local transport

U-Bahn and S-Bahn

The following U-Bahn and S-Bahn lines are operated by different companies. They are described in more detail in the articles Metropolitana di Napoli and Servizio ferroviario metropolitano di Napoli .

- Metro ( Metropolitana di Napoli )

- line 1

- Line 6

- Line Naples Piscinola – Giugliano – Aversa (no number, operated by MetroCampania NordEst )

- Train

- by Trenitalia operated, mostly unnamed lines ( Servizio ferroviario metropolitano di Napoli )

- Line 2: Pozzuoli Solfatara – Napoli Gianturco (urban line)

- Formia - Naples - Salerno

- Napoli Campi Flegrei - Capua

- Napoli Campi Flegrei - Castellammare di Stabia

- lines operated by private companies

- the six lines of Ferrovia Circumvesuviana in the east of the city

- the Ferrovia Circumflegrea and Ferrovia Cumana lines operated by SEPSA and operating in the west of the city, as well as line 7, which is under construction

- by Trenitalia operated, mostly unnamed lines ( Servizio ferroviario metropolitano di Napoli )

Buses and trams

There are three tram lines 1, 2 and 4 in Naples , but above all a dense bus network, as well as the Naples trolleybus . However, the three tram lines as well as two of the five trolleybus lines that were still in existence after several shutdowns in the years 2012 to 2016, including the M13 overland line to Aversa and Teverola, are not in operation (as of December 2019).

Ferries

Local transport also includes the ferries from the ports of Molo Beverello and Porticciolo di Sannazarro (Mergellina) , which go to all the islands and various mainland destinations in the entire Gulf region.

Mountain railways

Furthermore, three funiculars , called Funicolare (Funicolare di Montesanto , Funicolare Centrale and Funicolare di Chiaia) connect the Vomero hill with lower parts of the city. The fourth funicular is the Funicolare di Mergellina further west .

Culture

Buildings

In 1995 the entire old town (centro storico) of Naples was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The number of buildings that are considered worth seeing is correspondingly high there.

Fortresses

The three most important fortresses (Castelli) that shape the cityscape are Castel Nuovo , Castel Sant'Elmo and Castel dell'Ovo . The Castel Nuovo is located at the port, in front of the town hall square. It was built in the 13th century under the Anjou and had the function of a city castle, in which since then the armies of the foreign rulers of Naples (French, Spanish, etc.) have been housed. In the 15th century it was completely redesigned and expanded. The City Council of Naples met in the Sala dei Baroni (Hall of the Barons) until 2006, and the Museo Civico (Museum of the City History of Naples) is now housed in the west wing of the castle .

The Castel Sant'Elmo was built in the 14th century on the Vomero hill. There is a circular path on the walls of the fortress, from which there is an incomparable view of the entire city and the Gulf of Naples. Today the Castel is home to various cultural and scientific institutions, including the Biblioteca di Storia dell'Arte (Art History Library).

The third large fortress is the also accessible port castle Castel dell'Ovo . It is located on a small island in the sea (today connected to the mainland) and was built in the 9th century on the older foundations of a church from the 5th century. It received its present form in the 13th century. There is also a small area on the island with numerous restaurants.

In addition to these three Castelli there are other fortresses, including the Castel Capuano , located next to Porta Capuana , which received its current shape in the 19th century, was used for a long time as a dungeon and courthouse and is now an administrative building. The former Castello del Carmine and Caserma Garibaldi should also be mentioned .

Churches and monasteries

There are hundreds of churches and numerous monasteries in Naples. There are numerous showcases with images of saints in the streets. A religious center is the 13th century Duomo San Gennaro . In his Capella del Tesoro di San Gennaro , the relics and blood of the city saint, San Gennaro, are kept, who became well known for the so-called blood miracle. If the blood does not flow during the ceremony on May 1 of each year, it is said that the city of Naples is unlucky for a year. Under the cathedral you can still see the baptistery of an older church from the 5th century.

Another religious center is the Santa Chiara church and monastery complex . It was built in the 14th century and houses royal tombs, a well-known cloister, a Poor Clares choir and a museum. Santa Chiara was completely destroyed during World War II on August 4, 1943 when the city was attacked by 400 US bombers. With donations from the people of Naples, the church was rebuilt in the original Provencal Gothic style.

Behind the unspectacular facade of the Jesuit church Gesù Nuovo the splendor of a baroque interior unfolds unexpectedly. The church from the 16th century is centrally located in the square of the same name, directly opposite the Santa Chiara church .

The former monastery and today's museum Certosa di San Martino is located on the Vomero hill, just below Castel Sant'Elmo . Like this one, the Certosa di San Martino offers a beautiful view over parts of the city and the gulf. It was built in the 14th century, and in the 17th century the Carthusian monastery was completely redesigned in the Baroque style. Inside you will find a well-known cloister and a cultural and historical museum, the Museo Nazionale di San Martino .

There are two churches in Piazza San Gaetano . One is San Lorenzo Maggiore , a Franciscan monastery church from the 13th century with baroque alterations from the 18th century. Inside you can see floor mosaics from an early Christian predecessor, the Laurentius Church from the 6th century. Particularly noteworthy are the excavations under the church, it is an ancient marketplace from Greco-Roman times.

Architecturally , the Church of San Francesco di Paola , built in the classicism style, is very different from the other Neapolitan churches. It is located opposite the Royal Palace in Piazza del Plebescito .

In the baroque church of Cappella Sansevero you can find numerous marble sculptures. It was once the private chapel of Raimondo di Sangro (1710–1771), a noble inventor and alchemist. Two somewhat macabre exhibits in the basement of the church come from this, the preserved corpses of a man and a pregnant woman. What has been preserved are the skeletons and the complete blood vessels, crystallized by an unknown chemical that must have been injected into the two while they were still alive.

Other well-known churches are Santa Maria della Sanità , San Gregorio Armeno and San Domenico Maggiore .

Palaces and villas

Even more numerous than churches are the Neapolitan palaces ( palazzi ) and villas ( ville ), which were usually simply residential buildings of the upper class. Some of them are now administration buildings, others, mostly run down, are now also inhabited by lower social classes and students. The most famous palaces, however, are the much larger, former royal palaces.

The Palazzo Reale is the former palace of the viceroys and dates from the early 17th century. It is located in the Piazza del Plebiscito , today you can visit some halls, corridors and rooms of the royal family. The freely accessible national library is also housed here.

The Palazzo Reggia di Capodimonte (built from 1738) is also a former royal palace. The palace, which is surrounded by a large palace park, now houses a museum with paintings by Botticelli , Raffael , Titian and Caravaggio (see: Museums).

The synagogue is located in the Palazzo Sessa .

In the urban area and along the east coast ( Miglio d'oro ) there are hundreds of other palaces and villas, such as the Palazzo Spinelli di Laurino or the Castello Aselmeyer .

Universities and National Library

There are six universities in Naples. The largest and oldest is the University of Naples (Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II) . It was founded in 1224 by Frederick II as the third university in Italy after Bologna and Padua. Also of great importance are the Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli (founded in 1989) and the University of Naples L'Orientale (Università degli studi di Napoli L'Orientale , founded in 1732), an important European study institution for philology and linguistics of non-European languages. Other universities are the Università degli Studi di Napoli Parthenope (founded in 1920) and the Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa .

In addition, Naples is the seat of the Pontificia Facoltà Teologica dell'Italia Meridionale ( theological college) as well as the art school Accademia di Belle Arti , the Conservatorio di Musica San Pietro a Majella and the Università Telematica Pegaso . Internationally renowned non-university research institutions are the Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Storici ("Italian Institute for Historical Studies") and the Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Filosofici ("Italian Institute for Philosophical Studies"). The Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte (" Capodimonte Astronomical Observatory") was founded as early as 1812 and is now part of the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica .

The National Library ( Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli ) in the Palazzo Reale is a state public library and the third largest library in Italy after the national libraries in Rome and Florence . It has a book inventory of around 1,800,000 copies, as well as 19,000 manuscripts, 8,500 journals, 4,500 incunabula and 1,800 papyri .

In 1872 Anton Dohrn founded the Naples Zoological Station , in Italian Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, a biological research institute that is one of the oldest continuously existing bioscientific research institutions in the world.

Art and museums

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is one of the most important of its kind in the world. Above all, numerous finds from Pompeii and Herculaneum are on display , including many large sculptures and mosaics, including the famous depiction of the Battle of Alexander , which consists of one and a half million mosaic stones . Also worth mentioning is the Secret Cabinet (Gabinetto Segreto), a formerly closed room with a collection of erotic and pornographic art from antiquity.

The large picture gallery of the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in the Palazzo Reale di Capodimonte built by the Bourbons is also famous . Works from the 13th to the 20th century are exhibited here, including works by Titian , Masaccio , Vasari , Bellini , Raffael , Botticelli , Caravaggio , El Greco and Pieter Brueghel the Elder . The collection from the heyday of Neapolitan painting is unique in the world with works by Andrea da Salerno , Jusepe de Ribera , Massimo Stanzione , Bernardo Cavallino , Andrea Vaccaro , Mattia Preti , Luca Giordano , Francesco Solimena and numerous other artists.

The Pio Monte della Misericordia is one of the most important private art collections in the city . The adjoining church is famous for an altarpiece by Caravaggio.

There is also the Musei di Antropologia, Mineralogia e Zoologia dell'Università Federico II , a total of eight quite extensive and publicly accessible teaching collections of the university, the Museo d'Arte Contemporanea Donna Regina , the Museo Hermann Nitsch (with works by the Austrian artist Hermann Nitsch ), the Palazzo delle Arti di Napoli , a gallery for contemporary art and numerous other museums in the urban area and in the agglomeration around Naples.

Teatro San Carlo, Galleria Umberto, catacombs, cemeteries, Centro Direzionale and others

The Teatro San Carlo was built as an extension of the Palazzo Reale in the 18th century . After its completion in the 18th century, it was the largest opera house in the world and for decades one of the most important in all of Europe. It is still significant today and is best known for its sumptuous interior.

The Galleria Umberto I is one of the world's first large shopping arcades, which was built at the end of the 19th century based on the model of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan .

The catacombs Catacombs of San Gennaro are a two-story cemetery complex in the hills of Capodimonte, named after the martyr San Gennaro, who after his execution in Pozzuoli in 304 found his first resting place. The graves, carved into the rock, are richly decorated with frescoes and mosaics from the 5th to 9th centuries. In the Sanità district, under the church of Santa Maria della Sanità , you will find the Catacombe di San Gaudioso .

The monumental Real Albergo dei Poveri, built from 1750 to 1766 by the architect Ferdinando Fuga on behalf of Charles VII , was intended to accommodate the poor of the empire.

In addition to the main port, there are also some smaller ports in Naples. Some of them, such as the famous Porto di Santa Lucia , are now used as ports for luxury yachts , while others are still used for fishing.

The huge main cemetery of Naples, Cimitero di Poggioreale, is located in the Poggioreale district . The historic Fontanelle cemetery is well worth a visit . It has been in a huge cave in the Sanità district since 1656 . There is also the small cemetery of the (non-Catholic) English, the Cimitero degli Inglesi .

The so-called Centro Direzionale is a postmodern administrative center built in 1994 by the Japanese architect Kenzō Tange , which is considered the largest European of its kind.

The Maggio dei monumenti (May of Monuments) was created on the initiative of a married couple. In the meantime, over 200 museums, historical and cultural sites with local historical significance open their doors free of charge for the city's population and tourists every year in May.

Parks

A publication from 2010 lists 46 parks for Naples, many of which are less than one hectare in size. The two largest parks by far with extensive forest and meadow areas are the Parco di Capodimonte , which was originally laid out in 1734 and covers an area of 134 hectares, and the Parco dei Camaldoli (137 hectares). In 1807, on a French initiative, the Orto Botanico University was established . In addition, there is the park around the Villa Floridiana on the Vomero hill (6 ha) and above all the Parco Virgiliano , located next to the island of Nisida . It was built in the first half of the 1930s and covers 9.2 hectares.

music

16th and 17th centuries

For centuries, Naples had an almost mystical reputation as a city of music, where even the simplest people and peasants could sing and dance wonderfully and happily. From the early 16th century onwards, the form of Villanella , which originated in Naples, played with this myth - a seemingly (!) Rustic song with a comical , coarse or ironic touch, often in the Neapolitan dialect. Villanelles alla napolitana were, alongside the madrigal, the most important secular vowel form in Italy until the early 17th century, and were later also written by composers from other regions.

Naples experienced its first musical heyday at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries, especially in the field of keyboard music ( organ and harpsichord ), when composers such as Giovanni de Macque , Giovanni Maria Trabaci and Ascanio Mayone worked at the court of the Spanish viceroys created their own Neapolitan style of early baroque keyboard music, which had a particularly strong influence on Girolamo Frescobaldi . Trabaci and Mayone also published the first compositions expressly composed for (baroque) harp in 1601 and 1602 . At the same time, Prince Gesualdo da Venosa worked here with his eccentric madrigals. One of the first, and probably the most important prima donna of the early 17th century (and harpist) Adriana Basile also came from Naples.

Famous and almost unique in the 17th century (until around 1760) were the four great music conservatories in Naples , which emerged from the city's orphanages : the Poveri di Gesù Christo , the Santa Maria di Loreto , the Sant'Onofrio and the Santa Maria della Pietà dei Turchini . Hundreds of children were trained as musicians here. The departments for the castrati , from which numerous important singers emerged, were of particular importance . It was not until the second half of the 18th century that the Neapolitan conservatories fell into a crisis and the education was no longer as good as it used to be.

The most important Neapolitan composers in the middle of the 17th century were Giovanni Salvatore , Francesco Provenzale , Christofaro Caresana and Giuseppe Cavallo , who mainly created religious works. Their music was almost completely forgotten by the end of the 20th century and was only made known to an interested public again through the meritorious work and CD recordings of Antonio Florio and his Cappella de'Turchini .

Neapolitan Opera

The opera arrived in Naples with a certain delay around 1650, but in the first few decades mainly Venetian works were performed. It was not until 1680 that Alessandro Scarlatti, the first major opera composer, appeared in Naples. He also worked in Rome , but is often considered the founder of the so-called Neapolitan School , which had enormous success throughout Europe from the 1720s and brought up a light, rococo-like , gallant style . Its most important representatives include Leonardo Leo , Leonardo Vinci , Giovanni Battista Pergolesi , Domenico Sarro , Francesco Durante , but also Johann Adolph Hasse (a student of A. Scarlatti) and others. v. a. The first major opera house in Naples was the San Bartolomeo , which was replaced in 1737 by the construction of the huge San Carlo Opera House . Naples finally rose to the rank of music capital.

In addition to the late baroque opera seria , various variants of the comic opera were cultivated in Naples , the most famous early example of which La serva padrona (1733) comes from Pergolesi. In Naples itself there was also a tradition of commedia per musica in the Neapolitan dialect until the 19th century , for which there were separate small theaters that were particularly popular with the common people: the Teatro dei Fiorentini , the Teatro nuovo and the Teatro della Pace . In the second half of the 18th century, a second generation of the Neapolitan school worked with Niccolò Jommelli , Domenico Cimarosa , Tommaso Traetta and Giovanni Paisiello . Her works were played across Europe and also influenced the operas of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart .

Despite the crisis in the Naples Conservatories at the end of the 18th century, and although the time of the actual Neapolitan school around 1800 passed, the city continued to set the tone in the field of opera alongside Venice and Milan until the middle of the 19th century. The work of Gioachino Rossini as musical director of the Teatro San Carlo and the Teatro del Fondo (alongside the Impresario Barbaja ) between 1815 and 1822 went down in the annals of the opera . At that time, Rossini was in Naples with one of the best opera orchestras in Europe and an ensemble of leading virtuoso singers such as Isabella Colbran , Giovanni David , Manuel García , Andrea Nozzari and Giovanni Battista Rubini , for whom he wrote Otello , Armida and seven other operas. From 1822 to 1838 Gaetano Donizetti was musical director of the royal theaters. 19 of his operas were premiered in Naples, including Maria Stuarda (1834) and Lucia di Lammermoor (1835). Donizetti also worked in the 1830s as a teacher at the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella , where his contemporaries Vincenzo Bellini and Saverio Mercadante had also studied. The latter later also became the director of this institution and also premiered numerous operas on the Neapolitan stages (until the 1860s).

Since the middle of the century, the importance of the San Carlo Opera House compared to La Scala in Milan decreased somewhat, so that only relatively few of Giuseppe Verdi's operas (only early works) and not a single one of Giacomo Puccini's operas saw their world premiere in Naples. Today the Teatro San Carlo is one of the most important opera houses in Italy. Since 2008 there has been a large annual theater festival, the Napoli Teatro Festival Italia.

The most famous tenor of the early 20th century, Enrico Caruso , was from Naples.

Folk music

The traditional tarantella , whose roots go back at least to the 17th century, and which also found its way into art music and ballet in the 19th century and achieved international popularity, is very important. it was danced in this form by ballerinas such as Fanny Elssler .

Nowadays, when people talk about Neapolitan music, they mostly talk about the Canzone Napoletana , the Neapolitan folk music . It began in the 19th century and still has a significant influence on Italian popular music today. The Canzone Napoletana was created from the merging of earlier regional folklore traditions, some of which go back to the Middle Ages, with classical elements, in particular 19th century Italian opera. The dominant instruments of the very expressive music are guitar and mandolin, the singing is mostly in the Neapolitan dialect .

The pieces ' O sole mio and Funiculì, Funiculà became known far beyond the city limits . The important protagonists of Musica Napoletana also included famous opera tenors such as Enrico Caruso and Tito Schipa , later singers such as Roberto Murolo (1912–2003), Edoardo Bennato (* 1949) and Pino Daniele (1955–2015). One of the most famous Neapolitan groups that has been reviving traditional musical styles since 1967 is the Nuova Compagnia di Canto Popolare . The band Almamegretta fuses Neapolitan folk music with reggae and Arabic sounds.

At the Festival della Canzone Napoletana , which took place for the first time from 1952 to 1970 and was then revived in 1998, the best interpreters of Neapolitan music are awarded annually.

particularities

For centuries the city has been famous for the individually designed Neapolitan Christmas cribs , which are traditionally produced and sold in the workshops and shops in a separate old town street (Via San Gregorio Armeno) . Most families have their own, constantly growing nativity scenes, in the churches you can often find huge nativity scenes with a wide variety of figures, detailed everyday scenes and well-known Neapolitan buildings. The Neapolitan cribs differ from the North American-Central European type in their realism and richness of detail. Often there are also depictions of well-known contemporary people such as prominent footballers, Angela Merkel or Silvio Berlusconi .

The fireworks, which reach their traditional climax at the end of the year and envelop the entire city in noise and light, are also peculiar. Every year on the first weekend in May, on September 19 and December 16, the “miracle” of liquefaction is celebrated in the Cathedral of San Gennaro. Here goes one as a relic in a vial stored substance, allegedly from the dried blood of St. Januarius to exist in the liquid state of aggregation over. If the “miracle” does not occur, this means bad luck for the city. Chemists are pretty sure that it is a thixotropic substance that could have been made by the alchemists of the Middle Ages. However, this scientific explanation leaves the believers unimpressed. After the lack of blood liquefaction in 1980, there was a severe earthquake, and in 1988 the SSC Napoli narrowly missed the Italian championship.

Food culture

“One day I will return to Naples because it is my home that I love. But not to sing, but to eat pizza. "

The pizza is said to have been invented in Naples and the typical Neapolitan pizza differs significantly from the Roman pizza, among other things by the much thicker, somewhat raised edge. Together with pasta, it is still the most important dish in town. Industrial pasta production using a pasta machine was also invented in Naples . Among the pizzas, the pizza margherita and the pizza fritta are the most common. Together with the pasta, they form the cucina povera , the common people's kitchen. Naples is also known for dishes with fish and seafood.

A pastry specialty of Naples are the sfogliatelle , puff pastry pockets with ricotta filling. Naples is also famous for its espresso , which is not only said to have a special taste, but also shapes the entire cityscape through its frequent enjoyment.

Sports

Naples is the home of the traditional soccer club SSC Napoli , which is deeply rooted in the city and is passionately and unconditionally supported by the Neapolitans. The "light blue" (Azzurri) play their home games in the Stadio San Paolo (today 55,000 seats) in the Fuorigrotta district . With the help of Diego Maradona , who is still revered today , the club celebrated its greatest successes, becoming Italian champions twice (1987, 1990), winning the Italian Cup (1987), the Super Cup and the UEFA Cup (1989). In 2004 the SSC Napoli went bankrupt, in 2007 it was promoted to the top division, in 2012 it won the Italian Cup again and was among the 16 best teams in Europe (round of 16 of the UEFA Champions League ). The last successes of SSC Napoli are the Italian Cup 2013/14 and the Italian Super Cup 2014.

The CN Posillipo club is one of the world's best known and currently most successful water polo clubs. The Neapolitans won the highest crown in European club water polo in 1996, 1997 and 2005 with the Champions League and the EuroLeague. In 2012 the America’s Cup sailing regatta took place right off the coast of Naples. In June 2012 it was announced that the Giro d'Italia 2013 will start again in Naples for the first time in 50 years. Most recently, the second most important cycling stage race made a stop in Naples in 2009 . The Ippodromo di Agnano racecourse with a capacity of 30,000 is located in the 19th district of Fuorigrotta . The basketball team Basket Napoli plays its home games in the PalaBarbuto hall .

Naples is the venue for the 2019 Summer Universiade .

history

Before the founding of Naples by the Greeks, the Campania region was populated by Italian peoples, the Oscans (also: Campanians), the Samnites and the Etruscans .

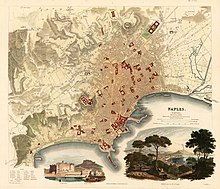

The Greek and Roman Neapolis

Around 700 BC BC - in the course of the Greek colonization - Greeks from the nearby Kyme ( Cumae ) founded the settlement Parthenope in today's city of Naples, named after the siren Parthenope . The seaside settlement was at the foot of the Pizzofalcone hill . Since about 530 BC A second polis arose in the north-east of the port of Parthenope , which Parthenope exceeded as early as 470. From then on Parthenope was also called Palaiopolis (old city). The new city in the area of today's old town was named Neapolis (new city). The Neapolis, laid out according to the Hippodamian scheme and surrounded by a city wall, was one of the most prosperous cities in Italy and Magna Graecia for centuries .

The history of Campania in the 4th century BC BC was marked by the expansion of the emerging Roman Empire , which wanted to establish a kind of sovereignty over Neapolis in 328. However, Naples refused, so Rome sent an army to enforce its demands. Naples now got between the fronts of the Romans and Samnites , with whom they initially allied. Eventually the city besieged by the Romans was overthrown , the Samnite garrison was driven out and the gates opened to the besiegers. A thereupon 326 BC The alliance treaty concluded with Rome (a foedus aequum) made Naples a municipium and formally guaranteed the city a certain independence and internal autonomy. The Greeks remained an extremely influential ethnic group well into Roman times, and their city remained a formally independent city-state ( polis ) for around 250 years . It was not until Naples in the Roman Civil Wars 88–82 BC. BC stood on the wrong side, it was then formally incorporated into the Roman Empire under Sulla as a dependent provincial town. Even in the early imperial period , when Emperor Nero visited the city, Naples was clearly a city with a distinct Greek influence, even if the Romanization progressed inexorably. It is estimated that early Roman Naples had between 16,000 and 30,000 inhabitants, excluding houses and villages outside the city walls.

Some remains of both the Greek and Roman cities still exist. Part of the Greek city wall, which was reinforced in Roman times, can be seen in Piazza Bellini , remains of the Acropolis at Caponapoli in the northwestern part of the old town, ancient thermal baths in the Museo dell'Opera di Santa Chiara and the remains of the Roman Theater of Naples directly houses and courtyards of Vico Cinquesanti built on it . The main square ( agora or forum ) has been located under today's Piazza San Gaetano since the foundation of Naples , where you can still see the columns of a Greek temple and the buildings of the Roman market that are now below the surface. The course of the street in today's old town is still roughly identical to that of the ancient city. Three parallel main streets, including the Via Tribunali, have crossed the city from west to east since it was founded (Greek plateiai , Roman decumani ), they are connected by numerous cross streets ( stenopoi or cardines ) . The hypogea on Via dei Cristallini have also been preserved .

During Roman antiquity, Campania was not only regarded as a particularly productive agricultural region (especially in the cultivation of grain and viticulture), as evidenced by the saying campania felix (happy Campania), but also as a place of idleness for the aristocratic upper class. In the vicinity of Naples there were a number of bathing and thermal baths (such as Baiae , Pompeii ) and not only on Posillipo there were numerous luxury villas.

Odoacer, Ostrogoths, Ostrom

In 476, Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman emperor to rule in Italy, effectively took over the government and formally submitted to the Eastern Roman emperor who resided in Constantinople . He was named Patricius Romanorum and was recognized by the Emperor Zenon for some time as the (de facto independent) administrator of Italy under Eastern Roman rule. In 493, after a four-year war, the Ostrogoths under Theodoric the Great took over rule, which lasted in Naples until 536.

In 536 the still important Naples was conquered by Eastern Roman troops after a long siege. The general Belisarius succeeded in this by sending a few hundred men through the underground aqueduct of Naples. From here, Belisarius continued his conquest of Italy. But the Ostrogoths offered fierce resistance and their new king Totila won the city back again in 543. In 553 Ostrom conquered the city again after the Ostrogoths had finally defeated Narses . This ended late antiquity in Italy .

Lombards and Byzantium, Duchy of Naples

But the Lombards began to conquer Italy as early as 568, and in 581 they occupied Benevento . The remaining Eastern Roman-Byzantine areas were directed and defended by the Exarchate of Ravenna , to which ducats were subordinate. One of these ducats became Naples in 661; From there, Byzantium tried in vain to conquer Benevento two years later. Byzantium, which from 633 was confronted with the Arab world power and at the same time Slavic invaders in the Balkans, gradually lost control over Italy, which was only on the periphery of the empire with the loss of Carthage (698) at the latest. One of the dukes who tried to break the dependence on Constantinople was Stephen II (755-800), under whom there was an rapprochement with the Pope, especially since the Lombards had conquered Ravenna in 751 . He minted his own coins for the first time in 763. Only after the death of Antimo (801–818) did Constantinople regain direct control by a Protospatharios . Three years later, the local elite took over under Stephan III. power again. In 840 the title of duke even became hereditary.

The Duchy of Naples , practically independent in the late 8th century, prevailed against the Dukes of Benevento and the Dukes of Salerno, who tried to conquer the city. In 836 it even allied itself briefly with the Muslims, who conquered Sicily from 827 and established themselves in some places on the mainland. In 846 there was an attack on Rome. The Emir of Palermo conquered Ischia and led his army along Vesuvius. In 849 a papal-Campanian fleet struck back Saracens before Ostia, in 871 Byzantium and Venice as well as troops from the empire, plus Croatian and Dalmatian auxiliaries, conquered Bari . Byzantium thus succeeded in renewing its old claims to the entire south of the peninsula.

In conflict with Byzantium, the Lombard prince (princeps) Pandulf Eisenkopf built up an area of power at the end of the 10th century that included the principality of Capua , the duchy of Benevento , the duchy of Spoleto and the margraviate of Camerino. Pandulf paid homage to Emperor Otto I. Pandulf's death in 981 threatened the disintegration of the entire power bloc, because Byzantium had by no means given up its claims to sovereignty over the Lombard principalities. After 981, Emperor Otto II tried to subordinate the Lombard principalities to his rule. However, he died in 983.

In the 1020s, Naples was independent from Byzantium, but the city began to change. Like many cities in Italy, it was increasingly self-organized, fighting for independence from the duchy. The sources for this are, however, thin, at least we learn from the annals of Benevento for the year 1015 of a "communitas prima", for the year 1042 of a "coniuratio secundo". In 1134 the duke was forced to come to an understanding with the Neapolitans. Duke Sergius VII concluded a pactum with the city nobility, the "mediani", and the entire population. The duke promised inviolability of person and property, freedom of movement for all traders; He also promised to discuss any changes to the law or taxes with the nobility and not to undermine these agreements. War and alliance should also no longer be decided by the duke alone, but in consultation with the city tour. When Sergius VII died in 1137, the municipality together with the bishop established an aristocratic republic.

But this only existed until the conquest by the Normans in 1140, when the Neapolitans also managed to maintain their privileged position for a long time.

Normans

Under Rainulf Drengot, the Normans had won their own territory north of Naples for the first time since 1027 with the county of Aversa . 1047 was Emperor Heinrich III. Accompanied by Pope Clement II, advanced south to clarify the political situation in the Lombard principalities. He withdrew the principality of Capua from Waimar IV, who sought hegemony in this area. But a little later Waimar reappeared as a feudal lord of the Normans.

The Normans not only made themselves independent of their liege lord, they conquered all of southern Italy (until 1071) including Sicily (until 1091). The Duchy of Naples was besieged from around 1134 to 1136 under Roger II , finally defeated and incorporated into the Norman Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1140 . At that time, Naples already had about 30,000 inhabitants. The most important Campanian city at that time was Salerno . Both the original construction of the fortress Castel dell'Ovo and that of Castel Capuano go back to the Normans. Compared to other cities, Naples was able to achieve a high degree of autonomy and economic independence, which in the long term benefited its position in the expanding Norman Empire, while Amalfi and Gaeta lost their economic supremacy. The basis and climax was the royal privilege of 1190, which placed Naples directly under the king. The township was organized under consuls headed by the compalazzo appointed by the king .

Staufer

But in 1194 the Hohenstaufen , who had seized all of southern Italy in a short campaign (Naples fell in August 1194), came under Henry VI. in their place. They deprived Naples of its privileges. Heinrich's son and successor Friedrich II founded the University of Naples , which bears his name today, the first state university in Europe. He introduced a centralized administration by command-bound officials, which differed greatly from the contemporary ideas of feudalism. Urban autonomy only had room as long as it served its political and economic goals.

Anjou

The Hohenstaufen rule in Naples did not last long after Frederick's death in 1250. The French house of Anjou established a new rule when Charles I of Anjou conquered the kingdom of the two Sicilies and held it as a fiefdom of the Pope from 1266. After bitter disputes with the Hohenstaufen heirs, Charles I was able to defeat the Hohenstaufen in 1266 and 1268. Konradin , the last male Hohenstaufen, was beheaded in Naples in 1268 in the Piazza del Mercato .

Under the Anjou, Naples regained considerable importance when they made it the capital of the Kingdom of Sicily . Since 1270 new city walls, new urban areas and a port near the markets in the east as well as numerous churches have been built. The Anjou also had the fortresses of Castello del Carmine and Castel Sant'Elmo built and, from 1279, Castel Nuovo, which served both as a port defense and as a royal residence .

By 1300 Naples already had 50,000 inhabitants. The court's need for luxury stimulated trade, which was dominated primarily by the Florentines, but also by Genoese, Venetians, Catalans and Marseilles. From 1278 onwards, the gigliato was minted as its own silver coin, which remained of great importance until the 15th century. The Crown Archive in Castel Capuano, which had already been established by Wilhelm I, was continued.

Even if their rule, which lasted until 1442, was marked by brutal repression in domestic politics, they ensured an economic and cultural heyday of the city and took fundamental urban planning measures to modernize it.

Aragon, Habsburg

In 1442, the Spaniards defeated the Crown of Aragon under Alfonso , the last ruler of the French Anjou, and large parts of the city and the fortress belt that had already been incorporated into the suburbs were destroyed. Under the Aragonese, the economic ties between Naples and the Iberian Peninsula were intensified, the economy as a whole promoted and the city became a center of Renaissance and humanism . The city wall was provided with city gates where suburbs had arisen, and the city wall and fortifications were completely renovated and expanded.

Even after the displacement of the Aragonese, Naples remained under Spanish rule. These were replaced by the Habsburgs in 1503 (until 1707) and the previously independent Kingdom of Naples was annexed to the Spanish-Habsburg Empire as a tributary province. The Spaniards, who were not only economically but also militarily superior, stationed 5,000 soldiers in Naples, built defense systems along the coast and rebuilt the fortress Castel Sant'Elmo , which is located on a hill above the city . However, under the Spanish viceroys of Naples , extensive urban development measures began. The old town was renovated and increased, the legislature centralized and moved to Castel Capuano . In the triangle between Pizzofalcone, Castel Sant'Elmo and Castel Nuovo , new neighborhoods, predominantly inhabited by the Spaniards themselves, have been built (including the grid-shaped soldiers' quarter of the Quartieri Spagnoli ) and separated from the city of the Neapolitans by the newly built Via Toledo instead of the old city wall . The newly built city walls and fortresses in the Spanish area were not only used for fortification against external enemies, but also as a symbol of surveillance and submission. The seat of government was moved from Castel Nuovo to the newly built Palazzo Reale in the area of the city inhabited by Spaniards. Over the next two centuries, the Neapolitan aristocracy began to move from the old town towards the Spanish districts.

The townspeople were rewarded for their controllability with low taxes and bread prices, as the seat of government of the viceroys, university town and thanks to its international port, the town flourished. Due to the massive influx of poor rural populations, but also of the rural nobility, the population rose rapidly to 300,000 in 1700 and made Naples one of the largest cities in Europe. The negative consequences were overpopulation, uncontrolled growth in the suburbs, poor hygiene and homelessness of the lower classes. At the same time, the luxury of living in the upper classes (nobility and merchant class) developed, resulting in numerous palaces and monasteries that have shaped the cityscape to this day. This period was mainly influenced by the viceroy Pedro Álvarez de Toledo (1532–1553). On the one hand, the ambitious ruler forced administrative reforms and urban redevelopment; on the other hand, he relied on repression such as the introduction of the Inquisition in Naples, which was prevented by a popular uprising in 1547.

Revolts, Republic of Naples, Austrian Habsburgs

The rule of the Spanish Habsburgs, which lasted until 1707, was interrupted for months by revolts and the proclamation of the Republic of Naples ; these events are considered part of the "17th century crisis". In July 1647, social tensions erupted in an uprising triggered by a tax increase on fresh vegetables. The 27-year-old fisherman and fruit trader Masaniello , who led the anti-Spanish revolt and took power in the city for ten days after its victory, is still very popular in Naples to this day. Behind the fisherman stood Giulio Genoino, who had spent 18 years in prison for his demands for democratization. The revolt ended when the Spanish viceroy had their leader Masaniello murdered in the monastery of Santa Maria del Carmine against the resistance of Cardinal Ascanio Filomarino .

Not much later, in October 1647, the Republic of Naples was proclaimed in the hope that France would support the republic which encompassed large parts of southern Italy. Instead, a Spanish fleet bombarded Naples, and the leaders of the republic had to surrender on April 6, 1648. The old balance of power was restored and after another minor rebellion in 1649 the Neapolitans surrendered to their fate. On top of all this, the city was struck by a devastating plague in 1656 , killing thousands of residents, in June it is said to have been 400 per day, in July already 1,500 per day. Due to the mass of dead, they began to be transported to the city's tufa caves. The population placed little value on scientific advice; once again they put their hope in processions and prayers; those who could fled to the country.

In the War of the Spanish Succession , Naples rose again on July 7, 1707, and Austria took over the city in August. In 1734 Vienna handed the city over to another branch of the Bourbons, on the condition that Naples would never be united with Spain.

Bourbons

A clear improvement in the situation only occurred when the Bourbons , who had acquired the Spanish throne as a result of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1712, took over Naples from the Austrians in the War of the Polish Succession in 1734 . Under Charles VII , who ruled the newly formed Kingdom of the Two Sicilies from 1735 to 1759 and then ruled Spain, a vigorous reform policy was initiated. Charles VII, a representative of the Enlightenment , took action against corruption, broke the power of ecclesiastical dignitaries, made structural changes in the cityscape and promoted cultural life and science; so began the excavations of Herculaneum in 1738 . Giambattista Vico became a court historian. Pietro Giannone, who was too frank about church and state, was banished to Vienna. Antonio Genovesi of the University of Naples became the first professor of political economy and Ferdinando Galiani , as secretary of the embassy in Paris, kept in touch with the most important contemporary philosophers. The administration was modernized and it supported trade. She was supported by Tuscan and Spanish advisers such as the Marquis of Salas Montealegre or Bernardo Tanucci, a professor at the University of Pisa . In 1759 Charles renounced the throne to become King of Spain.

His underage son Ferdinand IV succeeded him as ruler, so Bernardo Tanucci was in charge of state affairs. But the famine of 1764, coupled with a massive epidemic, killed 40,000 Neapolitans, perhaps 200,000 across the empire. She threw back the reforms. Queen Maria Carolina took the opportunity, together with church forces and conservative nobles, to overturn the reform course. The daughter of the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa forced Tanucci to resign in 1776.

Naples, with its high population density and the steadily increasing rural population, had great potential for unrest even under Ferdinand IV. A preventive political measure was enough bread and games like the Cuccagna spectacle regularly donated by the king (paese di cuccagna means land of plenty ). Ferdinand is referred to as Re Lazzarone (roughly: 'King of the Beggars'), who disparaged intellectual activity and did not share the goals of the Enlightenment and reform politicians, but had a good relationship with the lower classes.

Parthenopean Republic, Napoleonids

In view of Napoleon's successes in his Italian campaign , the royal family fled to Palermo in 1798. In January 1799, French revolutionary troops under General Jean-Étienne Championnet entered Naples. A group of elite republicans (bourgeois and aristocratic intellectuals, lawyers, medical professionals, young nobility educated in the military academies and involuntary clerics appointed by their families), the majority of whom came from the provinces, then proclaimed the Parthenopean Republic for 144 days . Their political concepts, ideas and models of thought probably sounded strange and incomprehensible to the majority of the population; in any case, the republic met with little approval.

Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo and his "Christian Army of the Holy Faith" (the "Sanfedists") had been moving from Calabria to the revolution and enlightenment since February . When he marched into Naples on June 13, the French had already withdrawn. The riots and executions that followed immediately afterwards by the army and the lower class of Naples cost their lives around 100 members of the intellectual elite - more precisely the emerging bourgeoisie and the reform-minded part of the aristocracy, including almost all members of the Provisional Government. The Bourbons returned to the city.

In the winter of 1805/06 the Bourbons and with them the Spaniards were again ousted, this time by the Napoleonic French. For the first time in southern Italy, they installed a constitutional monarchy with political participation of the subjects. Despite its economic and military dependence on France (a satellite state), the Regno di Napoli possessed extensive sovereignty. The French secularized the state and introduced a socio-political order based on rationality. Feudalism was abolished in August 1806, and the monastic property was nationalized in February 1807, as was welfare for the poor and the school system. A state central administration was established and scientific and cultural institutions were established ( Capodimonte observatory , botanical garden, zoological museum) or handed over to the public ( Teatro San Carlo , libraries, museums). The most momentous measure, however, was the introduction of the civil code in 1809. While Joseph Bonaparte (1806–1808) still held key positions predominantly with French, his successor Joachim Murat (1808–1815) awarded posts to circles of civil and enlightened Neapolitans. The living conditions of the lower classes, however, remained the same, also due to the nationalization of the poor and sick care that had been taken over by the church and the upper class. A report by Consiglio provinciale Napoletano in 1808 speaks of poverty, misery and the situation of street children. Nevertheless, investments were made in the Chiaia district, which was already inhabited by the nobility and wealthy at that time , where boutiques and cafés were built and the beach promenade was renovated.

Restoration, Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Garibaldi

With Napoléon's fall came the end of the Napoleonic kingdom of Naples, Ferdinand returned to Naples on June 17, 1815. Ferdinand implemented a ruthless restoration policy that also removed the last traces of French reform efforts. Accordingly, in 1820 there was a first uprising of the Carbonari , soldiers rebelled in Nola and Avellino . Under General Guglielmo Pepe the movement reached Naples, the king signed a declaration, but did not intend to give in. In 1821 the Austrian army occupied the city and stifled the revolt. In 1848, as in all of Europe, there was another revolution. Ferdinand had to accept a constitution, and a meeting was held in the monastery of San Lorenzo. With the help of Swiss mercenaries, Ferdinand eliminated the government. One of the leaders of the revolution, Luigi Settembrini , escaped from prison. He only returned after Garibaldi landed in Sicily in May 1860 and entered Naples on September 7th.

Kingdom of Italy, division of the country into two parts

Since 1860, the history of Naples has been closely merged with the history of the Kingdom of Italy , which is now beginning . On September 7, 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi entered Naples after conquering southern Italy. On October 21, 1860, the Neapolitans voted in a plebiscite with an overwhelming majority for annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, which lasted from 1861 to 1946. Francis II , the last Bourbon ruler, had fled the city to the fortress of Gaeta . He announced his surrender on February 13, 1861 and was declared deposed.

However, many Neapolitans identified only to a very limited extent with the new Italian state, whose starting point and center of power lay in Piedmont , in foreign northern Italy. Many development projects and funding measures of the new central government benefited mainly the north of the country, while the south was neglected and economically heavily burdened by an unjust and tough tax policy. Necessary reforms to eliminate the problems that arose during the Bourbon rule (e.g. land reform) were not carried out - also due to the intervention of the large landowners in the south. The government failed in its task of unifying the country internally. The north prospered economically in the first decades after the founding of the kingdom and soon caught up with the leading European industrial nations, while the south remained in poverty and agony. Naples also retained all the characteristics of a typical Mezzogiorno city . Poverty, crime, the shadow economy and mafia-like structures that reached into the highest political and economic centers of power shaped the city.

In 1884, as a result of poor infrastructural and hygienic conditions, Naples fell victim to a cholera epidemic, which was particularly devastating in the overpopulated poorer districts . As a result, a law (Legge per il Risanamento delle città di Napoli) was passed in 1885 , which provided for the redevelopment of the city, a new, more hygienic drinking and sewage system and newly built residential areas. In addition, a trail was pulled through the old town to the wide street Corso Umberto I create. An industrialization that began at the beginning of the 20th century with quasi-planned economy methods was doomed to failure due to poor planning, a lack of infrastructure and money seeping into dark sources and did not lead to any improvement in the economic situation. So it came to the first big wave of emigration to Northern Italy, Argentina and especially to the USA.

fascism

In this situation, fascism found significantly more supporters in southern Italy than in the north of the country. In 1922, shortly before the march on Rome , a large fascist congress was held in Naples. After Mussolini came to power , the problems in southern Italy were initially overlaid, concealed and pushed into the background by the imperial aspirations of the fascists and later by the Second World War . In 1938 Adolf Hitler was in Naples on a state visit to Mussolini.

The architecture of the fascist era shaped parts of the cityscape. This is how the Stazione Marittima di Napoli and the area of the Mostra d'Oltremare were built. In the center the Piazza Matteotti was built, on which five large buildings were erected, such as the Palazzo delle Poste and the Casa del Mutilato .

During the Second World War, the city was bombed by American planes from December 4, 1942 to 1943. Around 1,900 people were killed in numerous air strikes. Numerous industrial plants, the train station and the port were the main targets of the attacks, but many houses and a number of churches were also destroyed. After Mussolini's deposition and arrest in 1943, Naples was occupied by Wehrmacht troops in September . The Neapolitans were briefly exposed to the German terror regime. In the barricade and house-to-house fighting that began on September 27 (the four days of Naples ), the city's residents managed to free themselves on their own before the Allies arrived on October 1, 1943, and to drive the occupiers out of the city. But the German troops mined many houses and destroyed the water filter systems. In 1944 there were renewed air raids, this time by the German Air Force.

After the Second World War

The ensuing American occupation initially found chaos. The US military administrator Charles Poletti , who had been in office since June 1944, cleaned the police and administration of fascist elements with particularly great severity. As a consequence, he had to use the help of the mafia boss Vito Genovese, who fled the USA to Italy in 1937, and the local Camorra , which served him as a factor of order instead of the disbanded fascist police and thus gained permanent strength in the reorganization of urban life . The needs of the GIs and the favorable exchange rate of the dollar were the ideal breeding ground for the flourishing underground economy in Naples, which included around 40,000 prostitutes.

In the referendum of 1946 on the future form of government, the inhabitants of Naples (and southern Italy), in contrast to the majority of the country, voted to retain the monarchy. During the subsequent constitution of the Italian Republic , Enrico De Nicola, a Neapolitan, was elected its first president. In the first decades of the young republic, nothing essential changed for the Neapolitans about the precarious conditions in the city.

This led to another great wave of emigration, again Northern Italy and the USA, but also the Federal Republic of Germany as a flourishing economic wonderland, were the preferred destinations of the emigrants. The government in Rome directed billions in subsidies to southern Italy through the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno ("Treasury for the South"), which was founded to build the south , but these partially disappeared without the planned projects ever being built or they were badly invested.

Naples experienced an unprecedented amalgamation of economy, politics and Camorra for Europe in the second half of the 20th century, and the name of the city became synonymous with corruption, building speculation and illegal enrichment. The protagonist of this policy in Naples was in particular the mayor Achille Lauro (1952–1958 and 1961), who was close to the monarchist right . Having come into possession of a naval and financial empire through dubious methods, he used the position of mayor primarily to further expand his economic and political power. Nevertheless, he was popular with the population as a typical populist who pursued a pronounced panem-et-circenses policy . Lauro's compulsory dismissal by decree of the Roman central government did not fundamentally change the situation. Almost all of his successors copied this policy, whether they were Christian Democrats or Socialists .

In 1980, severe earthquakes struck Campania , killing 2,914. As a result, Naples was confronted with large numbers of homeless immigrants for a long time.

Present: renewal, changing government alliances, economic crisis