Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa of Austria (born May 13, 1717 in Vienna ; † November 29, 1780 there ) was a princess from the House of Habsburg . The Archduchess of Austria and Queen among others, who ruled from 1740 until her death . of Hungary (with Croatia ) and Bohemia were among the formative monarchs of the era of enlightened absolutism . After the death of Wittelsbach Charles VII. In 1745 she reached the election and coronation of her husband Franz Stephan toRoman-German emperor . With no domestic power of his own and no significant military or political talent, Franz Stephan devoted himself above all to the financial security of the imperial family, in which he was very successful. The affairs of state of the Habsburg Monarchy were carried out by his wife alone. Like every wife of an emperor, although not crowned herself, she was dubbed empress.

Maria Theresa had to pass the War of the Austrian Succession immediately after assuming power . Although it lost most of Silesia and the County of Glatz to Frederick II of Prussia in the Peace of Aachen in 1748 and the duchies of Parma and Piacenza and Guastalla to Philip , Infante of Spain, it was able to preserve all other Habsburg possessions. As a result, she pursued a comprehensive reform policy in various areas. This included the state organization, the judiciary and education . In economic policy it pursued a newer form of mercantilism . In the spirit of enlightened absolutism, the importance of the classes and particular forces was pushed back and the central state was thereby strengthened. In terms of foreign policy, Maria Theresa sought a compromise with France . After the Seven Years' War she had to give up Silesia for good. Galicia acquired it in the course of the First Partition of Poland .

After the death of her husband in 1765, she made her son Joseph II , who had already been crowned Roman-German king in 1764 as the designated successor to his father, as co-regent in the Habsburg hereditary lands. However, due to different political ideas, the cooperation between mother and son turned out to be relatively difficult. Joseph II was the first monarch of the House of Habsburg-Lothringen , founded by his parents , which ruled until 1918.

Life

Early years

Archduchess Maria Theresia Walburga Amalia Christina of Austria was born on May 13, 1717 as the second child of Emperor Karl VI. and his wife Elisabeth Christine von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel born in Vienna . Her older brother Leopold Johann was born in 1716 and died that same year. Maria Theresa remained as the eldest of three daughters of Emperor Charles VI, who was thus the last male descendant of the Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg .

In order to secure the female succession, which is unusual on the European mainland (differently in England and Scandinavia) according to the Salian law of succession ( Lex Salica ), Charles VI had. The Pragmatic Sanction was already issued in 1713 . This determined on the one hand that the country could not be divided by heredity, and on the other hand that his eldest daughter could succeed him in the absence of a male heir to the throne. He thus canceled the succession of the Salic law , which excluded the succession of daughters.

Maria Theresa received the usual good upbringing for female descendants of the ore house , but was not explicitly prepared for the role of heir to the throne. Her nurse and educator ( Aja ) was Countess Karoline von Fuchs-Mollard , called the fox , who became the Aja of the two Archduchesses Maria Theresia and Maria Anna after the death of her husband Christoph Ernst Graf Fuchs in 1728 . How important Karoline von Fuchs-Mollard was is clear from the fact that she was the only non-Habsburg woman to be buried in the Capuchin crypt.

Maria Theresa's upbringing focused primarily on religious issues, which significantly influenced her later decisions. The fact that she viewed religion as important connected her to her predecessors and differentiated her politics from that of her two successors. The traditionally good language training included classes in Latin, Italian and French. While Italian was still the preferred language in the imperial family under Leopold I , Maria Theresa preferred French and communicated mainly in French with her children. Maria Theresa herself described the shortcomings of her upbringing in her political memoranda of 1750 and 1755: “To be able to have the experience and knowledge necessary to rule so widely stratified and distributed countries all the less, as my father would never be willing to do it to consult external and internal business, or to inform: so suddenly I saw myself stripped of money, troops and advice. "

Marriage and family

In view of the forthcoming inheritance, the question of the marriage of Maria Theresa became an important issue in European politics. Various marriage candidates were considered. This included a son of Philip V of Spain , who later became Charles III. of Spain , with the prospect of reconnecting Spain with Austria. Great Britain and the Netherlands spoke out against this, who feared a disturbance of the balance of power and therefore only wanted to accept a husband from a less powerful house. Another possibility, particularly favored by Prince Eugen, would have been her marriage to the heir of the Bavarian electorate . After all, the decision was made by Maria Theresa herself, namely for her marriage to Franz Stephan von Lothringen . He had lived at the Viennese court for a long time, Maria Theresa knew and liked him, and Emperor Karl was not averse either. The marriage took place on February 12, 1736 in Vienna in the Augustinian Church. As part of the European equilibrium policy, Franz Stephan had to forego his duchies of Lorraine and Bar , but was entitled to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, which was free after the expected extinction of the Medici (1738).

The couple shared a deep affection, also because they valued each other even before marriage. The marriage was quite happy, although Franz Stephan had various affairs. His favorites included Countess Colloredo, the vice-chancellor's wife, Countess Palffy, a lady-in-waiting of his wife, and Princess Maria Wilhelmina von Auersperg , a daughter of his tutor and friend Count Wilhelm Reinhard Neipperg . The marital relationship resulted in 16 offspring. Among them were the two future emperors Joseph II and Leopold II , the Cologne Elector Maximilian Franz and Marie Antoinette , who through their marriage to Louis XVI. Became queen of France. Maria Theresa sometimes cared for her children overprotective. This did not rule out a strict training program which the mother personally developed for her large group of children. The schedule included dance lessons, theater performances, history, painting, spelling, civics, a little math, and learning foreign languages. The girls were also instructed in handicrafts and conversation.

Takeover of government

After the death of her father in 1740, Maria Theresa's succession to the throne was in jeopardy despite the right to it that she received through the Pragmatic Sanction. At the beginning of her government, Maria Theresia relied on her father's advisory staff, which included, among others, the Obersthofkanzler Philipp Ludwig Wenzel von Sinzendorf , the Hofkammerpräsident Thomas Gundacker Graf von Starhemberg and the convert and secret state secretary Johann Christoph Freiherr von Bartenstein . In retrospect, Maria Theresa did not express herself very positively about most of her advisors: “Instead of encouraging me, all my employees let it sink completely, even pretending that the situation was not at all desperate. It was I alone who retained the most courage in all of these tribulations and who, with childlike trust and frequent prayer, appealed to God's help. "Bartenstein, however, expressly excluded her from this criticism, even emphasizing" that he alone was responsible for maintaining this monarchy. Without him everything would have come to an end. "

War of the Austrian Succession

Although her father had tried everything to get the Pragmatic Sanction recognized in Europe, it was called into question after his death. The House of Wittelsbach established its inheritance claim to a will from Ferdinand I from 1543. The Saxon dynasty registered claims to the Bohemian electoral dignity. The Prussian King Friedrich II also relied on old traditions to legitimize his claim to parts of Silesia. But above all he saw the uncertain situation in Austria as favorable to add Silesia to his empire. France also tended to go to war with Austria.

Taking advantage of Maria Theresa's uncertain situation as heir to the throne, Frederick II of Prussia began in the year of the death of Charles VI. the First Silesian War caused by the invasion of Silesia , which lasted until 1742. At the same time, Maria Theresa had to survive the War of the Austrian Succession . Opposite them were Bavaria, Spain, Saxony, France, Sweden, Naples, the Electoral Palatinate and Electorate of Cologne, whose rulers all asserted claims to at least parts of the empire. Maria Theresa only found support from her allies Great Britain and the Netherlands. Her husband advocated a settlement as early as the beginning of the war. But despite the desperate situation for her, Maria Theresa, as she later wrote, “acted heartily, hazed everything and strained all forces.” This different approach largely pushed Franz Stephan into political sideline during this time.

A ray of hope for her was that on the occasion of her coronation as Rex Hungariae (i.e. king, since a female functional designation was not intended), the Hungarian estates promised her the support of 20,000 soldiers.

In the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , however, things looked different. For the first time in centuries, the House of Habsburg was unable to prevail in the election of the emperor because there were no women in office. Instead, the Wittelsbacher Karl VII was elected. His actual power, however, was small despite his imperial dignity. Just one day after his coronation as emperor in Frankfurt am Main in February 1742, his capital, Munich, was conquered by the Austrian troops. In the same year Maria Theresa had to cede Silesia and the County of Glatz to Prussia in the Peace of Wroclaw . The actual war of succession was not yet over.

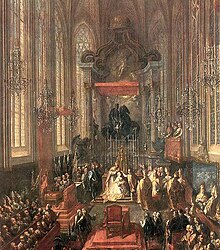

In 1743 Maria Theresa's troops succeeded in liberating Prague from the French who supported Bavaria. On May 12th of this year Maria Theresa was crowned Queen of Bohemia in St. Vitus Cathedral . At her request, the coronation was carried out by the Archbishop of Olomouc, Jakob Ernst von Liechtenstein-Kastelkorn . In 1744 Frederick II of Prussia attacked again and broke off the year-long Second Silesian War . After Prussian victories, Maria Theresa had to confirm the loss of Silesia in the Treaty of Dresden in 1745 . The Austrian War of Succession itself was not very successful, but the Austrian side did not suffer any serious defeats.

After the death of Charles VII in 1745, a political success was the enforcement of the election of Franz Stephan as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. From then on, Maria Theresa also called herself “Roman Empress”, but did not have herself formally crowned to one due to her multiple royal dignity, although this had been the custom for imperial wives since the coronation of Kunigunde in 1014.

The War of Succession ended in 1748 with the Peace of Aachen after both sides were unable to achieve decisive military successes . Maria Theresa had to confirm the loss of Silesia once again, and the Habsburg Empire also lost the duchies of Parma and Piacenza and Guastalla to the Spanish Infante Philip of Chinchón . Despite the strong threat, Maria Theresa had succeeded in establishing herself as the rightful heir to the throne of Charles VI. to claim.

Reform policy

Even during the war, Maria Theresa turned her attention to internal reforms. Its far-reaching changes came to be known as the “Theresian State Reform”. The actual planner was initially the administrative officer Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz , and since the 1760s State Chancellor Wenzel Anton Kaunitz has played an increasingly important role. The camera scientist Joseph von Sonnenfels and the physician Gerard van Swieten as a reformer of the University of Vienna should also be mentioned .

The Empress did not hesitate to learn from Prussia in her reforms. This applies, for example, to an administration that is detached from the estates, to military reform and to educational policy. Politics was carried by the spirit of enlightened absolutism . Maria Theresa herself wrote: "So a sovereign prince is guilty of using everything to receive or relieve his countries and subjects as well as their poor, but by no means to waste the money collected with merrymaking, sovereignty and magnificence."

A common thread of their reform policy was that the traditional and fragmented estates institutions should be replaced by a central, absolutistically governed state apparatus. In fact, the importance of the estates and the right of the nobility to have a say in the hereditary lands was increasingly repressed during their reign and was ultimately limited essentially to the rights of the landlord.

State organization

Their reforms began in 1742 with the creation of the House, Court and State Chancellery as an authority with above all foreign policy competencies. The actual reform policy then began after the end of the War of the Austrian Succession, among other things because, given the high costs of the war, the reform of state finances was particularly urgent, which is why Maria Theresa announced the levying of additional taxes for the government and the military. This marked the beginning of a fundamental reorganization of the Austrian tax system. The now general tax liability also included the nobility and clergy for the first time. A general cadastre was introduced as the basis for taxation (“ Theresian Cadastre ”), which was also important for financial and economic policy.

In 1749 a directorate in publicis et cameralibus was established. It had political and financial powers that previously lay with the court chamber . The Austrian and Bohemian court chancelleries merged into the new central authority, which centralized and strengthened the government. Subordinate bodies were created in a hierarchical structure below the central authorities. For the individual countries, with the exception of the Austrian Netherlands and Hungary, where the previous corporate institutions were able to hold, supreme authorities and a district organization below them were created. This also served as a certain protection of the peasants from the arbitrariness of the landlords. The powers of the Directory continued to grow and from 1756 also included the rights of the General War Commissariat. In the long run, however, the headquarters proved to be too cumbersome, so that in 1761 responsibility for financial management was outsourced again. The authority was renamed the Austrian and Bohemian Court Chancellery .

A State Council was set up under the influence of Kaunitz . This should serve to advise the rulers, but could also submit applications to them. The Council of State consisted of three members of the gentry and three members of the knighthood or scholars.

Army reform

The course of the Austrian War of Succession made it clear that the army was in need of reform. Maria Theresa doubled the strength of her army and an army reform was carried out. The reform was mainly planned by Leopold Joseph von Daun , Karl Alexander von Lothringen and Joseph Wenzel von Liechtenstein . The hitherto imperial army became an Austrian army. The Prussian army, opponent in the War of the Austrian Succession, became an important model. In 1751 Maria Theresa had the Theresian Military Academy built in Wiener Neustadt .

The regular army had a nominal strength of 108,000 men. This did not include the border guards at the military border in south-eastern Europe with around 40,000 men. The Seven Years' War showed that the quality of the army had improved significantly. On the occasion of the victorious Battle of Kolin in 1758, the ruler donated the Maria Theresa Order . As of 1764, the Order of Saint Stephen was considered a civil counterpart .

Judicial reforms

Significant reforms of the judiciary took place during Maria Theresa's time. The organization of the Reichshofrat was improved and the monarch created a supreme court whose task it was to uphold the law in the Austrian lands. The patrimonial jurisdiction of the landlords was severely restricted, as were the powers of many city courts. The different forms of jurisdiction in the various territories opposed the centralization of the state. Maria Theresa had the rights of the countries collected in the Codex Theresianus published in 1769 . Legal standardization should be undertaken on this basis. With the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana, it introduced uniform criminal law for all Habsburg countries - with the exception of Hungary - for the first time. In terms of content, it was entirely shaped by traditional law. Enlightenment and natural law did not yet play a role. It was not until 1776, under the influence of her son Joseph, that torture was abolished.

Educational policy

Education policy played an important role . The Silesian Augustinian abbot Johann Ignaz von Felbiger , who had been sent to Austria by Friedrich II, played an important role . In 1760 a central authority for educational policy was created with the “Study and Books Censorship Court Commission”. Maria Theresia regulated the school operation by introducing the general compulsory instruction in the general school regulations for the German normal, secondary and trivial schools in all of the imperial royal hereditary countries (signed on December 6th, 1774). One-class elementary schools for six to twelve year old children have been set up in the countryside.

Basic knowledge included religion, reading written and printed texts, current script , arithmetic in five species, and guidance on righteousness and economics. In the (three-class) secondary schools, the following were also planned: written essays, geometry, housekeeping, agriculture, geography and history. Already in the first Theresian school regulations, importance was attached to "that not only the memory should be seen, nor the youth plagued with memorization about the necessity, but the understanding of the same should be enlightened".

When Maria Theresa died, 500 of these trivial schools were already in existence. However, it was by no means possible to teach all the children. The number of illiterate people remained relatively high. Secondary schools with three classes were set up in the cities. The teachers received their training in normal schools. There was also a reform of the higher education system. In the higher education sector, the abolition of the Jesuit order , which also controlled the University of Vienna, played an important role in 1773. The university has now passed into the state's area of responsibility. The medical faculty of the University of Vienna has been better equipped and the university has been expanded to include the new auditorium . To this day, lessons are still being taught in the former Knight Academy Theresianum in Vienna, which she founded . In addition, other special schools and academies were founded for certain professions. In 1770 the mining academy was founded in Schemnitz (today Banská Štiavnica - Slovakia) .

Economic reforms

In economic policy, Maria Theresa followed a more recent form of mercantilism , such as that propagated by Joseph von Sonnenfels . The aim was to increase the population, secure food and create new income opportunities. A flourishing economy had a positive impact on tax revenues and ultimately helped maintain a large army. The competition with Prussia was also an important factor in economic policy, Maria Theresa endeavored to compensate for the loss of Silesia with economic development in other areas.

A personal peculiarity was her preference for spinning , which was supposed to keep the population everywhere from idleness and laziness: The feudal spinning duties were reactivated (1753), all children were to learn to spin in winter (1765), even the soldiers and their families had to go through Show constant spinning "industrialism".

Country and city, peasant class and bourgeoisie should remain separate in their time. The town remained a place of handicrafts, while in the country only the most necessary manual trades remained - this separation between town and country seemed necessary to Maria Theresa in order to maintain the equilibrium. However, new factories and similar businesses should also be located in the countryside. Initially, following the example of Charles VI. Monopolies were still granted, which was abandoned in the time of Maria Theresa because privileges were not beneficial for economic development in the long term. As a result, efficient textile production developed in Bohemia and Moravia. The willingness of the nobility to invest in new businesses had a positive effect. In the German part of the monarchy this willingness was less pronounced. In Tyrol, the mercantile industrial policy even failed because parts of the population resisted the settlement of factories.

The rules of the guild were abolished because they prevented the economy from growing. In foreign trade, exports were forced, while imports were restricted by customs duties. In the area of domestic trade, customs and toll stations were dismantled with the aim of creating a uniform economic area. In a customs regulation of 1775, Bohemia and the Austrian hereditary lands were merged into one customs area. The transit areas of Tyrol, Vorarlberg and the foreland remained as before. Another customs union consisted of Hungary, the Banat and Transylvania. The remaining territories each had their own customs areas. In the area of transport, new canals and roads were built and the postal system improved.

With regard to the rural population, Maria Theresa sought relief. Serfdom was restricted. The landlord's misuse of robot work should be dealt with by a landlord commission. Robot patents were issued in 1775, 1777, and 1778, which limited corporal labor .

Since 1749 so-called manufacture tables have been created for the different regions and attempts have been made to record the employment of the population in the individual economic sectors. A regional division of labor should be based on an overall poor data basis. Hungary was then declared an agricultural area without further ado. Commercial development would have been ruled out. Ultimately, however, this project failed due to resistance in the territories.

Population policy

The promotion of the economy also included the promotion of immigration to the areas of Hungary that were depopulated during the Turkish wars of the past. Most of the settlers came from territories of the Holy Roman Empire . The goals were multi-layered: On the one hand, the newly acquired areas were to be secured against the Ottoman Empire. On the other hand, it was also about preventing unrest in Hungary by settling German settlers. Maria Theresia founded so-called impopulation commissions. These recruited settlers in the densely populated regions of the empire. But there were also coercive measures: Protestants from the hereditary countries, dissatisfied peasants, homeless lower classes and even prisoners of war from Prussia were brought to south-east Europe. The new settlers not only improved agriculture, but also in Upper Hungary (present-day Slovakia) and in Transylvania , efficient coal-mining economies emerged. In the area of the Temescher Banat the population increased between 1711 and 1780 from 25,000 to 300,000 inhabitants.

Religious policy

In religious terms it was shaped by baroque Catholicism, but reformist currents also played a role. However, under the influence of Jansenism , she became increasingly pious. Maria Theresa created a chastity commission to combat immorality . Until the end of her life she strictly resisted exercising tolerance towards non-Catholics, which led to a serious conflict with her son Joseph. The repeal of the Jesuit order in 1773 did not come from her, but rather unwillingly carried out the papal ban. Maria Theresa fought Protestantism especially in Austria. The evicted Protestants were settled in remote and sparsely populated areas such as Transylvania , the Banat or the Batschka .

It also pursued a restrictive policy towards the Jews through stricter Jewish regulations (1753, 1764), which included compulsory beards and the wearing of the yellow spot . After the First Silesian War and the end of the Prussian occupation of Prague in 1744 in the Second Silesian War, it had 20,000 Jews deported from Prague and finally from all of Bohemia, before mitigating this in 1748 because the economic damage was too great. Despite Maria Theresa's anything but Jew-friendly policy, the foundations were laid for a flourishing of Jewish life in the imperial capital Vienna, both before and during her time. With the help of the payments imposed on prosperous court Jews such as Wolf Wertheimer , Marx Schlesinger , Simon Michel Preßburg, and the Hirschl family, it was possible to pay for magnificent representative buildings in Vienna such as Schönbrunn Palace, the Karlskirche or the imperial court library on Josephsplatz (today's National Library). The Portuguese court factor Diego d'Aguilar should be mentioned as an important financier of Maria Theresa, but at the end of 1749 he had to flee from Vienna.

Imperial politics

With regard to imperial politics, her husband, Emperor Franz I Stephan , was responsible. In view of the insignificant practical importance of the imperial crown, it is noteworthy that in 1749 Maria Theresa and her husband asked the conference ministers to provide expert opinions on the question of whether it still made sense to hold on to the imperial crown. The answers varied. In the end, it was an argument by Franz Stephan that prevailed. "How the empire cannot be maintained without the support of the ore house, so the separation of the ore house from the rich would be exposed to the same many and great dangers." In fact, the kingdom played an important one again during the Seven Years' War , which was also fought as an imperial war Role.

Foreign policy

Their domestic and foreign policy was aimed at defeating Prussia “in the field” and regaining possession of the annexed areas. The Prussian king remained their enemy. Over time, her remarks about Frederick II took on almost insulting forms. She spoke of the "monster" and "wretched king."

Against this background, the focus in Vienna was on restructuring the alliance systems. In terms of personnel, this becomes clear when Minister of State Bartenstein was replaced by Kaunitz-Rietberg in 1753. Kaunitz had already campaigned for rapprochement with France in 1749 . The alliance between Prussia and Great Britain in the Westminster Convention in 1756 appeared extremely threatening. Against this background, rapprochement with France was more important for Vienna than the centuries-old enmity between the Habsburgs and the neighboring country. In the same year, an Austro-French defensive alliance was formed. This meant the Renversement des alliances , the reversal of the previous European alliance system. This reorientation was also reflected in Marie Antoinette's marriage to the French heir to the throne. Russia was also allied with Austria .

Friedrich II marched on August 29, 1756 in Electoral Saxony - an ally of Austria. This started the Seven Years' War . In addition to the struggle for Silesia, which Maria Theresa had not yet given up, the war was a global conflict, especially between France and England for power overseas. The war itself dragged on for years without either side being able to achieve decisive successes in the European theater of war. For example, the Austrians won at Kolin , Hochkirch or Kunersdorf . The Prussians won the battles at Roßbach , Leuthen and Torgau , among others . The war ended in 1763 with the Treaty of Hubertusburg , with which Silesia finally fell to Prussia.

In order to at least partially compensate for the loss of Silesia, Maria Theresa participated in the first partition of Poland in 1772 . Thereby she acquired Galicia and Lodomeria . The empress found this aggressive policy difficult, but in the end the interests of the state prevailed. Friedrich II. Commented: "She wept, but took." After 1765 her son Joseph became co-regent. However, there were also differences of opinion on foreign policy. This is how he ended Maria Theresa's colonial policy . In 1773 Joseph prepared the acquisition of Bukovina through annexation. Whose willingness, after the death of the Bavarian Elector Maximilian III. To enforce Austrian claims by force in the War of the Bavarian Succession met criticism from Maria Theresa. After all, the Innviertel came to Austria by contract in 1779.

Marriage policy

Maria Theresa, who saw herself primarily as the ruler of the multi-ethnic state of Austria , tried to marry her children as advantageously as possible and hoped that marriages with the Bourbons would increase the power of the House of Austria (see also the Habsburgs' marriage policy ). The sons and daughters had to subordinate their own will to the welfare of the state and marry people whom their mother had chosen for them.

Maria Theresa and her Minister of State Kaunitz pursued the goal of improving Austria's political relations with foreign states and Austria's position in Europe . Maria Theresa knew that family ties often strengthened her influence on foreign policy, and therefore forged marriage plans for her 14 surviving children very early on. With wise foresight - taking into account the actions of Frederick II of Prussia - she concentrated in the context of these marriage plans above all on expanding family connections to the Bourbons then ruling in France , Spain , Naples-Sicily and Parma , and the resulting improved communication between Habsburgs and Bourbons.

The first marriage project of a series of planned connections between Bourbon and Habsburg was the marriage between Maria Theresa's eldest son, Archduke Joseph, who later became Emperor Joseph II, and Maria Isabella of Bourbon-Parma . Next, Joseph's brother Leopold, who later became Emperor Leopold II , had to consent to his mother's plans and marry Princess Maria Ludovika of Spain . The third son, Archduke Ferdinand Karl and later Duke Ferdinand of Modena-Este , was married by Maria Theresa to the heiress of Modena, Duchess Beatrix of Modena-Este .

Compared to the smooth implementation of her sons 'marriage projects, Maria Theresa was confronted with numerous problems during her daughters' marriage negotiations. The eldest daughter, Archduchess Maria Anna , remained unmarried due to her poor health. The marriage project, which is about to be realized, the marriage between the beautiful Archduchess Marie Elisabeth of Austria and the French King Louis XV. , failed because the young archduchess suffered from smallpox . While Archduchess Marie Christine of Austria as the only her husband, Duke Albert of Saxe-Teschen could choose themselves, Archduchess was Maria Amalia of Austria against their will and with violent resistance on the part of young woman with Duke Ferdinand I of Bourbon-Parma married . Archduchess Johanna Gabriela of Austria and her sister Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria both died of smallpox, so that Archduchess Maria Karolina had to take the place as the bride of King Ferdinand I of Naples-Sicily . The marriage of Maria Karolina's favorite sister, Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria, and the later King Louis XVI. of France was Maria Theresia's last and most ambitious marriage project.

Builder

In 1755 Maria Theresa acquired the Schloss Hof hunting lodge from Prince Eugen's heirs . From 1725 to 1729, under the direction of Lucas von Hildebrandt, a tranquil refuge for Prince Eugene of Savoy, which was known for its courtly festivities, was built there. In order to create space for guests and courtiers, Maria Theresa added one floor to the building, essentially giving it its present-day appearance.

The building of Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna is associated with the name Maria Theresa . The former hunting lodge of Joseph I designed by Fischer von Erlach , the Karl VI. had given to his daughter, she had the head of the building department, Nikolaus Pacassi, rebuilt 1743–1749. The result was a completely different room layout and a separate theater. The upgraded Schönbrunn building became the favorite palace of the empress. She spent the summer months there with her family. Maria Theresa had the Gloriette built in the Schönbrunn Palace Park as a memorial to commemorate the Battle of Kolin , in which Austrian troops defeated Friedrich, who was considered insurmountable, for the first time on June 18, 1757 in an open field battle.

Pacassi designed for her, among other things. also the redouten hall wing of the Hofburg new (1760).

In 1762 Maria Theresa acquired the Blauensteiner Hof and the adjoining Prucknerische Haus in Laxenburg . From 1756 there was a major renovation and expansion by the court architect Nikolaus Pacassi . The Belvedere (paintings in it by Joseph Pichler) was set up around 1770. Pacassi modified the building, whereby the entrances were relocated from the east to the north side towards the palace square. It became the imperial summer palace and was the favorite residence of Maria Theresa.

Last years and death

The worst personal stroke of fate was the death of Franz Stephan in 1765. She wrote: “I lost a husband, a friend, the only object of my love.” After his death, Maria Theresa only wore black widow's costume. In memory of her husband, she donated the women's monastery in Innsbruck. Joseph succeeded his father as emperor and was co-regent of Maria Theresa. The relationship between the two was fraught with conflict. Despite her willingness to reform, Maria Theresa was strongly influenced by Catholicism and the baroque tradition of the House of Habsburg. Quite different from Joseph, who pursued an Enlightenment policy. Maria Theresa rejected many of Joseph's ideas as anti-church, and the son could not easily enforce his goals against his mother, who was still in charge of the state.

After Maria Theresa's death on November 29, 1780, her burial was as follows, according to the court protocol: “The dead kai [ser] l [iche] very high corpse, which in the meantime remained in the imperial room, was on the 30th Opened at 7 p.m. and embalmed. The eccentricity lasted from 7 a.m. to 11 a.m., with the k. k. Protomedicus Kohlhammer were present. The opening and embalming was carried out by the imperial body surgeons Jos [eph] Vanglinghen, Ferdinand von Leber and Anton Rechberger, although the court pharmacist Wenzel Czerny also made use of it. On Friday, December 1st, early in the morning, the corpse was exposed in the large court chapel on a mourning scaffolding four steps high under a black canopy in the humble clothing of a spiritual habit . On the right hand was the silver cup with the heart in it; to the left on the 3rd season down from the head of the cauldron with the bowels. "Furthermore, the protocol says:" On Saturday the 2nd in the afternoon the beaker with the heart was solemnly in the Loreto chapel and after this the cauldron with the bowels in brought the duke's crypt to St. Stephen. On Sunday, December 3rd, as the day designated for the solemn burial ”, the body was buried in the Vienna Capuchin Crypt in the“ Maria Theresa Crypt ”in a double sarcophagus on the side of her husband, who had died in 1765. The funeral service for Maria Theresa in St. Stephen's Cathedral, organized by the Vienna City Council, did not take place until January 1781. Maria Theresa is one of those 41 people who received a “ separate burial ” with the body being divided between all three traditional Viennese burial sites of the Habsburgs (imperial crypt, heart crypt, ducal crypt).

Pedigree

| Pedigree of Empress Maria Theresa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old parents |

Emperor Ferdinand II. (1578–1637) |

King Philip III (Spain) (1578–1621) |

Count Palatine Wolfgang Wilhelm (Pfalz-Neuburg) (1578–1653) |

Landgrave Georg II (Hessen-Darmstadt) (1605–1661) |

Prince August II (Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel) (1579–1666) |

Duke Friedrich (Schleswig-Holstein-Norburg) (1581–1658) |

Count Joachim Ernst von Oettingen-Oettingen (1612–1659) |

Duke Eberhard III. (Württemberg) (1614–1674) |

| Great grandparents |

Emperor Ferdinand III. (1608–1657) |

Elector Philipp Wilhelm (Palatinate) (1615–1690) |

Duke Anton Ulrich (Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel) (1633–1714) |

Count Albrecht Ernst I of Oettingen-Oettingen (1642–1683) |

||||

| Grandparents |

Emperor Leopold I (1640–1705) |

Duke Ludwig Rudolf (Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel) (1671–1735) |

||||||

| parents |

Emperor Charles VI. (1685–1740) |

|||||||

|

Maria Theresa (1717–1780) |

||||||||

Female lineage since Albrecht I Elisabeth of Carinthia

- Elisabeth of Carinthia, Gorizia and Tyrol (* 1262, † 1313) ∞ Albrecht I of Austria , Roman King (* 1255, † 1308, son of Rudolf I of Habsburg )

- Anna of Austria (* 1275–1280, † 1327) ∞ Herman III. von Brandenburg and Coburg = Herman II. von Henneberg and Salzwedel (* 1275–1280, † 1308, Askanier )

- Jutta von Brandenburg and Coburg (* ≈ 1300, † 1353) ∞ Heinrich VIII. Count von Henneberg-Schleusingen (* ≈ 1288, † 1347)

- Sophie von Henneberg (* ≈ 1323, † 1372) ∞ Albrecht the Beautiful, Burgrave of Nuremberg (* ≈ 1319, † 1361, Hohenzollern-Nuremberg )

- Margarethe von Nürnberg (* 1359, † 1389–1391) ∞ Balthasar , Landgrave of Thuringia, Margrave of Meissen (* 1336, † 1406, Wettiner )

- Anna of Thuringia (* 1377, † 4 Jul 1395) ∞ Rudolf III , Elector of Saxony-Wittenberg († 1419, Ascanian )

- Scholastica von Sachsen-Wittenberg (* 1391–1395, † 1463) ∞ Johann I , Duke of Sagan (* ≈ 1387, † 1439)

- Margarethe von Sagan (* 1415–1422, † 1491) ∞ Volrath or Vollrad II., Count von Mansfeld (* ≈ 1380, † 1450)

- Margarethe von Mansfeld († 1468) ∞ Johann II, Count of Beichlingen († 1485)

- Felicitas von Beichlingen (* 1468, † 1500) ∞ Ernst IV, Count von Hohnstein , Lord in Lohra and Klettenberg (* ≈ 1440, † 1508)

- Anna II. Von Honstein († 6 Feb 1559) ∞ Albrecht VII, Count von Mansfeld-Hinterort (* 1481, † 1560)

- Katharina von Mansfeld-Hinterort (* 1520–1521, † 1582) ∞ Johann Georg I von Mansfeld-Vorderort , Lord of Eisleben (* 1515, † 1579)

- Esther von Mansfeld-Vorderort († 1605) ∞ Georg II, Baron of Criechingen († 1607)

- Anna Katharina von Criechingen († 1638) ∞ Johann Kasimir von Salm-Kyrburg (* 1577, † 1651)

- Anna Catharina Dorothea von Salm-Kyrburg (* 1614, † 1655) ∞ Eberhard III. , Duke of Württemberg (-Mömpelgard), (* 1614, † 1674)

- Christine Friederike von Württemberg (* 1644, † 1674) ∞ Albrecht Ernst I of Oettingen-Oettingen (1642–1683)

- Christine Luise von Oettingen-Oettingen (* 1671, † 1747) ∞ Ludwig Rudolf von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (* 1671, † 1735, Welfe )

- Elisabeth Christine von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (* 1691, † 1750) ∞ Karl VI. , Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria († 1685, † 1740)

- Maria Theresa

Male lineage since Albrecht I ∞ Elisabeth of Carinthia

- Albrecht I of Austria , Roman King (* 1255, † 1308) ∞ Elisabeth of Carinthia, Gorizia and Tyrol (* 1262, † 1313)

- Albrecht II of Austria (* 1298, † 1358) ∞ Johanna von Pfirt (Jeanne de Ferrette) (* 1300, † 1351)

- Leopold III. of Austria (1351–1386) ∞ Viridis Visconti (* 1352, † 1414)

- Ernst I of Austria (* 1377, † 1424) ∞ Cymburgis of Masovia (* 1394, † 1429)

- Friedrich III. , Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (* 1415, † 1493) ∞ Eleonore Helena of Portugal (* 1436, † 1467)

- Maximilian I , Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (* 1459, † 1519) ∞ Maria von Burgund (* 1457, † 1482)

- Philip I the Handsome, of Burgundy (* 1478, † 1506) ∞ Joan of Castile , the mad (* 1479, † 1555)

- Ferdinand I of Burgundy , Roman Emperor (* 1503, † 1564) ∞ Anna of Bohemia and Hungary (* 1503, † 1547)

- Karl (II.) Of Inner Austria (* 1540, † 1590) von Maria Anna of Bavaria (* 1551, † 1608)

- Ferdinand II of Austria , Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (* 1578, † 1637) ∞ Maria Anna of Bavaria (* 1574, † 1616)

- Ferdinand III. of Austria , Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (* 1608, † 1657) ∞ Maria Anna of Spain (* 1606, † 1646), cousin

- Leopold I of Austria , Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria (* 1640, † 1705) ∞ Eleonore Magdalene of the Palatinate (* 1655, † 1720)

- Charles VI , Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria († 1685, † 1740) ∞ Elisabeth Christine von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (* 1691, † 1750)

- Maria Theresa

Descendants of Maria Theresa

The marriage with the Roman-German Emperor Franz I Stephan gave birth to 16 children, six of whom died while their mother was still alive:

- Maria Elisabeth (1737-1740)

- Maria Anna (1738–1789), later lived in Klagenfurt

- Maria Karolina (1740–1741)

- Joseph II (1741–1790) ⚭ 1760 Princess Isabella of Parma , daughter of Duke Philip of Parma, Piacenza, Guastalla; ⚭ 1765 Princess Maria Josepha of Bavaria , daughter of Emperor Charles VII.

- Maria Christina (1742–1798) ⚭ 1766 Albert Casimir of Saxony, Duke of Teschen

- Maria Elisabeth (1743–1808), abbess in Innsbruck

- Karl Joseph (1745–1761), Archduke

- Maria Amalia (1746–1804) ⚭ 1769 Duke Ferdinand of Parma , son of Duke Philip of Parma, Piacenza, Guastalla

- Leopold II. (1747–1792) ⚭ 1765 Infanta Maria Ludovica of Spain from the house of Bourbon of Spain , daughter of King Charles III.

- Maria Karolina (1748–1748) Archduchess

- Johanna Gabriela (1750–1762), engaged to King Ferdinand I of Bourbon-Sicily

- Maria Josepha (1751–1767), engaged to King Ferdinand I of Bourbon-Sicily

- Maria Karolina (1752–1814) ⚭ 1768 King Ferdinand I of Bourbon-Sicily, son of King Charles III. from Spain

- Ferdinand Karl Anton (1754–1806) ⚭ 1771 Duchess Maria Beatrice d'Este , daughter of Duke Hercules III. from Modena

- Marie Antoinette (Maria Antonia) (1755–1793) ⚭ 1770 Ludwig (1754–1793), Dauphin , since 1774 as Louis XVI. King of France, son of the Dauphin Louis of France

- Maximilian Franz (1756–1801), Archbishop, Elector of Cologne

title

After the death of her husband Franz I Stephan in 1765, Maria Theresa bore the following "great title":

Maria Theresa, by God's grace Roman Empress, Wittib , Queen of Hungarn, Böheim, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Gallicia, Lodomeria, etc. etc., Archduchess of Austria, Duchess of Burgundy, Steyer, Carinthia and Crain, Grand Duchess in Transylvania, Margravine of Moravia, Duchess of Braband, Limburg, Luxembourg and Geldern, Württemberg, Upper and Lower Silesia, Milan, Mantua, Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, the Prince of Swabia, princes Countess of Habsburg, Flanders, Tyrol, Hainaut, Kyburg, Gorizia and Gradisca, Margravine of the Holy Roman Empire in Burgau, Upper and Lower Lusatia, Countess of Namur, woman on the Windischen Mark and Mechlin etc. , widowed Duchess of Lorraine and Baar, Grand Duchess of Tuscany, etc.

Even after her husband received the dignity of emperor in 1745, the term empress was used by herself and others. In addition to the other titles, she was referred to as Empress Maria Theresia or Maria Theresia of Austria , the latter often also being used for Maria Teresa de Austria, Infanta of Spain, and Queen of France (1638–1683). It was only after the Hereditary Empire of Austria was established in 1804 that she was referred to as Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria , Empress Maria Theresia of Austria or Austrian Empress Maria Theresia .

Appreciations

Since her work, the regent has been honored by various names. In addition, exhibitions, books and films are dedicated to her.

geography

- Maria Theresiopel was 1740-1918 the name of today's Subotica in what is now Serbia .

- Terézváros (German "Theresienstadt") has been called the VI since 1777. District of Budapest .

- Likewise, various places called Terezín were founded on the territory of today's Czech Republic, mostly during the rule of the regent.

- The Maria-Theresia-Reef (also Maria-Theresia-Insel) is a phantom island in the southern Pacific, which was allegedly discovered by US whalers around 1844.

building

- The Maria-Theresien-Schlössel , hunting lodge and formerly owned by the ruler

- the Maria-Theresien-Kaserne (since 1967) of the Austrian Armed Forces in Vienna

- the Maria-Theresien-Kaserne ( ung. "Maria Terézia Laktanya", built 1845) in Budapest

Warship

- the armored cruiser SMS Kaiserin and Queen Maria Theresa of the Austro-Hungarian Navy

Coins

- The Maria Theresa thaler is a historical coin minted since 1741, which was in use in the Orient and Africa until the early 20th century and is still minted as a silver coin today.

- In 1980 an Austrian 500 Schilling coin was minted on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the Empress' death.

music

The 48th Symphony (1769) by Joseph Haydn bears the nickname Maria Theresa , which was not the composer's name .

Street names, monuments (selection)

- Maria-Theresien-Straße in Vienna Inner City or Alsergrund (1870) and Maria-Theresien-Platz in the Inner City (1888)

- Maria-Theresien-Strasse in Innsbruck

- Maria-Theresien-Straße in Wels is the extension of the central ring road to the south-west, here the first building of the Welser Sparkasse and the regional court of Wels was built , and with the Maria-Theresien-Hochhaus in 1967 the tallest tower in Austria for a short time.

- Maria Theresa monument between the art and natural history museum with the associated four Triton and Naiad fountains (UNESCO World Heritage).

- Maria Theresa Monument in Marie Terezie Park in Prague, erected in 2020

Events, exhibitions, books

A folk festival called Terezijana has been taking place in Bjelovar, Croatia, since 1995 .

In 2017, for the 300th birthday of Maria Theresa, exhibitions took place in Vienna and Lower Austria. At the same time, Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger published a new, scientifically compiled biography.

Movies

- 1951: Maria Theresia - A woman wears the crown. , Feature film by Emil-Edwin Reinert with Paula Wessely in the leading role

- 1980: Maria Theresia , TV film by Kurt Junek with Ulli Fessl and Marianne Schönauer in the title role

- 2017–2019: Maria Theresia , TV series by Robert Dornhelm with Marie-Luise Stockinger (parts 1 and 2) and Stefanie Reinsperger (parts 3 and 4) in the title role

swell

- Friedrich Walter (Selected): Maria Theresia: Certificates, letters, memoranda (= The small library . 240). Albert Langen / Georg Müller, Munich 1942.

- Friedrich Walter (Ed.): Maria Theresia: Letters and files in a selection. (= Selected sources on German history in modern times . Volume 12). 2nd, unchanged edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1982, ISBN 3-534-03014-1 . (first edition 1968)

literature

- Alfred von Arneth : History of Maria Theresa. 10 volumes. Biblio-Verlag, Osnabrück 1971, ISBN 3-7648-0030-5 (reprint of the Vienna edition 1863–1879).

- Peter Berglar : Maria Theresa. With personal testimonials and picture documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2004, ISBN 3-499-50286-0 .

- Edward Crankshaw: Maria Theresa. The maternal majesty. (= Heyne biographies ). 9th edition. Heyne, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-453-55009-9 .

- Gabriele Marie Cristen: Maria Theresia; Between throne and love. Knaur-Verlag, Munich 2004.

- Franz Herre : Maria Theresa, the great Habsburg. Piper, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-492-24213-8 .

- Walter Koschatzky (Ed.): Maria Theresia and their time. For the 200th anniversary of death. Exhibition May 13 to October 26, 1980, Vienna, Schönbrunn Palace. Organized by the Federal Ministry of Science and Research on behalf of the Austrian Federal Government. Gistel, Vienna 1980.

- Thomas Lau : The Empress. Maria Theresa. Böhlau, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-79421-9 .

- Peter Reinhold : Maria Theresia. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-7973-0307-6 .

- Heinz Rieder: Maria Theresia. Ruler and mother. Diederichs, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-424-01477-X .

- Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger : Maria Theresia. The empress in her time. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-69748-7 .

- Adam Wandruszka : Maria Theresa. The great empress (= personality and history. Volume 110). Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen et al. 1980, ISBN 3-7881-0110-5 .

- Adam Wandruszka: Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , pp. 176-180 ( digitized version ).

- Juliana Weitlaner: Maria Theresia. An empress in words and pictures . Vitalis, Prague 2017, ISBN 978-3-89919-456-2 .

- Michael Yonan: Empress Maria Theresa and the Politics of Habsburg Imperial Art. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park 2011, ISBN 978-0-271-03722-6 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Maria Theresa in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Maria Theresa in the German Digital Library

- Works by Maria Theresa in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Maria Theresa in the Internet Archive

- Entry on Maria Theresia in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Maria Theresia: Children, Art and Cinema. Exhibition in the Imperial Furniture Collection, Vienna by Alexandra Matzner

- Heiner Wember: October 20, 1740 - Maria Theresa of Austria took office, WDR ZeitZeichen from October 20, 2015 (podcast)

Remarks

- ↑ Wolfsspur Magazin (ed.): A woman in male times . No. 2/2017 , p. 30-33 .

- ^ A b c Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka : The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 288.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 289.

- ↑ Georg Christoph Kriegl: Hereditary homage, which of the most luminous, great-powerful women, women Mariae Theresiae, Zu Hungarn, and Queen Böheim, As Ertz-Duchess of Austria, of the entire Nider-Austrian estates, of prelates, lords, knights, too Städt und Märckten very subserviently filed November 22nd, anno 1740. And by decree well-deserved praiseworthy gentlemen's estates, with all circumstances described in detail . Schilg, Vienna 1740 ( digitized version of the Bavarian State Library , Sign. Res / 2 Austr. 96 h).

- ↑ Quoted from Franz Herre: Maria Theresia, p. 47.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha, Graz 1992, p. 294.

- ^ Alois Schmid : Franz I and Maria Theresia. In: Anton Schindling, Walter Ziegler (ed.): The emperors of the modern times. 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany. Munich 1990, p. 235.

- ↑ Maria Theresa was crowned Queen of Hungary on June 25, 1741 in St. Martin's Cathedral in Pressburg . The Crown of St. Stephen was placed on her head by the Prince Primate of Hungary and Archbishop of Gran Emmerich Esterházy . Palatinus Count Johann Pálffy assisted with the coronation. (Quoted from Anton Klipp: Preßburg, New Views on an Old City. Karlsruhe / Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-927020-15-3 , p. 76f).

- ↑ Pressburg resolutions 1741. This promise is often considered to be the actual hour of birth of the later Kuk monarchy. Cf. Berglar 1984: 41, on military support: Hans Bleckwenn : Der Kaiserin Hayduken, Hussars and Grenzer - Bild und Wesen 1740–1769. In: Joachim Niemeyer (Ed.): On the military system of the Ancien Régime: Three basic essays (reprint in honor of the author on the occasion of his 75th birthday on December 15, 1987). Biblio, Osnabrück 1987, pp. 23-42. See quote: In this situation Maria Theresa placed herself under the protection of the Hungarians and on September 11, 1741 it was that she entered the assembly of the magnates in Pressburg, whereupon they heard from the short but eloquent speech of the young, beautiful princess , the oppressed woman and the pleading mother enthusiastic, drew their sabers and shouted: “Moriamur pro rege nostro.” (We will die for our king.) The Hungarians kept their word, they raised an army in the shortest possible time, and this armor did were sufficient to arouse terror among the enemy. According to BLKÖ: Habsburg, Maria Theresia (German Empress) Wikisource. See also Mittheilungen des kuk Kriegsarchiv, Volume 5, p. 109. THE VOLUNTARY BIDS ...

- ↑ Benita Berning: "After all the praiseworthy use". The Bohemian royal coronations of the early modern period (1526–1743). Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20082-4 , pp. 170-185.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 295.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, pp. 302, 306-308.

- ^ A b Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 300.

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: Maria Theresia. In: Ders. (Ed.): Lexicon on Enlightened Absolutism in Europe: Rulers - Thinkers - Subject Terms. Vienna 2005, p. 403.

- ↑ a b c d e Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 301.

- ^ A b Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 302.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 303.

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: Maria Theresia. In: Ders. (Ed.): Lexicon on Enlightened Absolutism in Europe: Rulers - Thinkers - Subject Terms. Vienna 2005, p. 404.

- ↑ Under the 5 species are understood: 1) counting, 2) adding, 3) subtracting, 4) multiplying and 5) dividing. Cf. Cohen, Salomon Marcus: Handbook of the entire arithmetic, or the entire bourgeois and commercial art of arithmetic, with all the necessary types of calculations, rules, examples, resolutions and explanations: for teachers and students in the most expedient way. 1805, p. 2 , accessed on June 27, 2019 (German).

- ^ Juliana Weitlaner: Maria Theresia. An empress in words and pictures . Vitalis, Prague 2017, ISBN 978-3-89919-456-2 , p. 109 .

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, pp. 303-305.

- ^ Fritz Blaich: Mercantilism. In: Handbook of Economics: (HdWW). Simultaneously new edition of the concise dictionary of social sciences, Volume 5, Stuttgart 1980, p. 248.

- ↑ Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Maria Theresia: The Empress in her time . CH Beck, 2019, ISBN 978-3-406-74114-2 ( google.de [accessed on April 9, 2020]).

- ↑ a b c Fritz Blaich: Mercantilism. In: Handbook of Economics: (HdWW). Simultaneously new edition of the concise dictionary of the social sciences, Volume 5, Stuttgart 1980, p. 249.

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: Maria Theresia. In: Ders. (Ed.): Lexicon on Enlightened Absolutism in Europe: Rulers - Thinkers - Subject Terms. Vienna 2005, p. 406.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 306.

- ↑ Kurt Schubert: The history of Austrian Jewry . Böhlau Verlag Wien, 2008, ISBN 978-3-205-77700-7 ( google.de [accessed on March 29, 2020]).

- ^ Karl Vocelka: Maria Theresa and the Jews. In: David. Retrieved March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: Maria Theresia. In: Ders. (Ed.): Lexicon on Enlightened Absolutism in Europe: Rulers - Thinkers - Subject Terms. Vienna 2005, p. 405.

- ↑ Tina Walzer: The living conditions of Viennese Jews in the time of Maria Theresa. Retrieved March 28, 2020 .

- ^ Alois Schmid: Franz I and Maria Theresia. In: Anton Schindling, Walter Ziegler (ed.): The emperors of the modern times. 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany. Munich 1990, p. 240.

- ^ Alois Schmid: Franz I and Maria Theresia. In: Anton Schindling, Walter Ziegler (ed.): The emperors of the modern times. 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany. Munich 1990, p. 242.

- ^ Alois Schmid: Franz I and Maria Theresia. In: Anton Schindling, Walter Ziegler (ed.): The emperors of the modern times. 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany. Munich 1990, p. 241.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 308f.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 309.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 312.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 310.

- ↑ http://www.schloss-laxenburg.at/cgi-bin/onlwysiwyg/ONL.cgi?WHAT=INFOSHOW&ONLFA=SLA&INFONUMMER=3851661 accessed on April 19, 2015.

- ↑ http://www.wikam.at/?content=willkommen_laxenburg.htm accessed on April 19, 2015.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, pp. 289, 313.

- ^ Walter Pohl, Karl Vocelka: The Habsburgs. A European family story. Edited by Brigitte Vacha. Graz 1992, p. 313f.

- ↑ Ernst Gurlt : Leber, Ferdinand Joseph Edler von . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, p. 93 f.

- ↑ From the court protocol quoted from Magdalena Hawlik-van de Water, Die Kapuzinergruft. Burial place of the Habsburgs in Vienna, second edition, Vienna 1993, p. 56.

- ↑ Walter Koschatzky (Ed.): Maria Theresia and their time. On the 200th anniversary of death, catalog for the exhibition May 13 to October 26, 1980 Vienna, Schönbrunn Palace, Salzburg / Vienna 1980, p. 202.

- ^ Franz Gall : Austrian heraldry. Handbook of coat of arms science. 2nd Edition. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-205-05352-4 , p. 50.

-

↑ Hungary. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 49, Leipzig 1746, Col. 1346-1381 (here column 1370). "After that, all kinds of foreign princes came to the Hungarian Crown, and this has granted, except for the current Queen and Empress Maria Theresa."

The New European Fama, which discovers the current state of the most distinguished courts , 141st part, 1747, p. 743: "Maria Theresa, by the grace of God Roman Empress, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, Ertz-Hertz-Herzogin of Austria uu We had hoped our enemies would [...]" ( Online in the Google book search)

Walter Frodl: Idea and Realization: Becoming the state preservation of monuments in Austria. Böhlau, Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-205-05154-8 , p. 181: Edict for the collection and storage of archival material of August 12, 1749: “We Maria Theresa by God's grace Roman cayser, in Hungarn and Böheimb etc. Queen, Ertz -Hert Duchess of Austria etc. etc. Offer all of these basic books our grace and [...] "( limited preview in the Google book search) - ^ Friedrich Schiller: Schiller's complete works. Volume 21, Georg Müller Verlag, 1804-1805, p. 425 (index): "Maria Theresia, Kaiserin von Oesterreich".

- ↑ Philipp Ludwig Hermann Röder: Geographical statistical-topographical lexicon of Italy according to its newest condition and constitution. Stettinische Buchhandlung, Ulm 1812, column 545: "The Empress Maria Theresia von Oesterreich founded a grammar school here after the establishment of German grammar schools." ( Online in the Google book search)

- ↑ Hochadeliche and godly assembly of the star cross called, which of Ihro kaiserl. Majesty Eleonora, widowed Roman empress, was erected in 1668. Chelensche Schriften, Vienna 1805, p. 164: “The most serene, most powerful Roman, and hereditary Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, in Germania, in Hungarn and Böheim, apostolic kings, Archduchess of Austria, Duchess of Lorraine, Venice and Salzburg etc., bored Royal princess of Sicily. "( Online in the Google book search)

- ^ Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Maria Theresia. The empress in her time. A biography. Munich 2017.

| Predecessors | Office | Successors |

|---|---|---|

| Maria Amalia of Austria |

Roman-German Empress 1745 to 1765 |

Maria Josepha of Bavaria |

| Charles II |

Archduchess of Austria 1740–1780 |

Joseph II |

| Charles III |

Queen of Hungary 1740–1780 |

Joseph II |

| Charles III |

Queen of Croatia and Slavonia 1740–1780 |

Joseph II |

| Karl Albrecht |

Queen of Bohemia 1743–1780 |

Joseph II |

| Charles II |

Duchess of Parma 1740–1748 |

Philip |

| Charles VI |

Duchess of Milan 1740–1780 |

Joseph II |

| Charles VI |

Duchess of Luxembourg 1740–1765 |

Joseph II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Maria Theresa |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 13, 1717 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 29, 1780 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Vienna |