Charles VI (HRR)

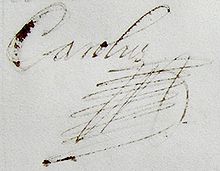

Karl's signature:

Charles VI Franz Joseph Wenzel Balthasar Johann Anton Ignaz (born October 1, 1685 in Vienna ; † October 20, 1740 ibid) was Roman-German Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1711 to 1740 as well as sovereign of the other Habsburg hereditary lands when Charles III. (Hungarian III. Károly ) King of Hungary and Croatia , as Karl II. (Czech Karel II. ) King of Bohemia , as Karl III. (Spanish Carlos III. ) designated anti-king of Spain , from 1713 as Charles VI. (Italian Carlo VI. ) King of Naples and through the Peace of Utrecht from 1713 to 1720 as Charles III. (Italian Carlo III. ) also King of Sardinia , and from 1720 as Charles IV. (Italian Carlo IV. ) King of Sicily .

In the War of the Spanish Succession , Charles VI. did not enforce his claim to the Spanish crown, but a large part of the Spanish possessions in the Netherlands and Italy fell to Austria. The Pragmatic Sanction was enacted during his time as emperor . This not only made possible the succession of female members of the House of Habsburg to the throne, but was also central to the emergence of a great power Austria by emphasizing the idea of union among the Habsburg states. The victory in the Venetian-Austrian Turkish War in 1717 resulted in territorial expansion. The territories gained were partially lost again in the Russo-Austrian Turkish War in 1739. He spent a large part of his reign imposing the pragmatic sanction within the Habsburg sphere of influence and gaining its recognition by the other European powers. In the interior, the emperor strove to promote the economy in the spirit of mercantilism . However, he gave up an important project with the Ostend East India Company in the interests of enforcing the Pragmatic Sanction. Nor did he achieve any reform of the administration or the military. He was the last emperor who, in addition to asserting the interests of the Habsburgs, also pursued an active imperial policy, although the imperial concept lost much of its importance in his time. He promoted art and culture in a variety of ways. His reign was a high point of the Baroque culture , the buildings of which still shape Austria and the former Habsburg states. With Karl's death, the House of Habsburg became extinct in the male line .

Origin and family

Karl (baptized as Carolus Franciscus Josephus Wenceslaus Balthasar Johannes Antonius Ignatius ) was the son of Leopold I from the House of Habsburg and Eleonores von Pfalz-Neuburg and the brother of Joseph I. His upbringing was under the supervision of Prince Anton Florian von Liechtenstein . The content was conveyed primarily by Jesuits such as Andreas Braun or people close to them. The mediation of traditional ruler's virtues and in particular the history of the Habsburg family played an important role. Two manuscripts have come down from Karl's childhood days in which he described the virtues of his ancestors.

Like every Habsburg he had to learn a trade, and he decided to train as a gunsmith . In the course of his training, Karl made a pen drawing of a falcon pipe at the age of sixteen, which is shown today in the permanent exhibition of the Army History Museum in Vienna. The drawing is signed by himself on the back piece ("Carl Erzh. Zu Oesterr.").

On April 23, 1708, Karl married Elisabeth Christine , the daughter of Duke Ludwig Rudolf von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel and his wife Christine Luise von Öttingen, and moved in with her on August 1, 1708 in Barcelona . The following children were born from the marriage:

- Leopold Johann (* / † 1716), Archduke

- Maria Theresia (1717–1780) ⚭ 1736 in Vienna Franz I Stephan of Lothringen

- Maria Anna (1718–1744) ⚭ 1744 Duke Karl Alexander of Lorraine

- Maria Amalia (1724–1730), Archduchess

War of the Spanish Succession

In view of the imminent extinction of the Spanish line of the Habsburgs after the death of Charles II , Emperor Leopold intended early on to make Charles King of Spain. Already during the Palatine War of Succession it was planned to send the emperor's son together with auxiliary troops to Spain, but this did not happen. However, the Spanish king himself did not designate Charles, but Philip of Anjou , a grandson of Louis XIV , to be the heir. After the king's death, Philip was recognized as king in Spain and the colonies. The resistance of Emperor Leopold, who allied himself with England and the Netherlands, triggered the War of the Spanish Succession .

After Charles' proclamation as King of Spain in 1703, Emperor Leopold and his brother Joseph granted him all Spanish possessions with the exception of Lombardy in a secret treaty. At the same time, a regulation on the succession in the House of Habsburg was concluded ( Pactum mutuae successionis ). From Portugal , Charles hoped to come to Spain in 1704. The Portuguese and English troops were too weak to break the resistance of the Spanish army. Taking advantage of the dissatisfaction of the Catalans and Aragonese with the regime of Philip V, they moved into the city in 1705 after the siege of Barcelona . Karl was able to expand his sphere of influence to Catalonia and other areas and raise his own troops. During this time he proved to be brave and tenacious, but showed little ability to integrate and lead. Pressed by the French, Karl had to vacate some positions as early as 1706. The allies' battles were also unsuccessful. So they had to vacate Madrid in June 1706. However, the Allies succeeded in conquering important Spanish possessions in Italy. At times, after military successes, Karl was able to move into Madrid in Spain in 1710, but soon had to retreat to Barcelona.

Beginnings of imperial rule and pragmatic sanction

The situation changed when his brother Joseph, now emperor, died in 1711 without male descendants. Charles now inherited Austria, Bohemia, Hungary and the prospect of the imperial title. Pressed from Vienna, he returned without giving up his claim to the Spanish throne. On his departure, he demonstratively appointed his wife to be governor in Spain. On 12 October 1711 it chose the electors to the Roman-German king . On 22 December 1711 he was in Frankfurt for Emperor crowned. From the beginning of 1712 he was back in Vienna. In the same year he was crowned King of Hungary. In view of the threatened unification of Austria and Spain in one hand, his allies left him in the War of the Spanish Succession, so that he had to renounce the Spanish crown. He held Barcelona for another year.

Domestically, he initially relied on continuity. For example, he expressed his confidence in Prince Eugene and confirmed the members of the Secret Conference . This and the influential Johann Wenzel Wratislaw von Mitrowitz advised to renounce the Spanish throne. Nevertheless, the emperor did not join the Treaty of Utrecht between France, Spain on the one hand and Great Britain and the Netherlands on the other in 1713. However, the return of his wife and the Habsburg troops had been agreed beforehand. A short time later, after further defeats, he charged Prince Eugene with negotiations that led to the Peace of Rastatt in 1714 . In the Peace of Baden he was awarded the former Spanish possessions in Italy Milan, Mantua, Sardinia, Naples without Sicily and the formerly Spanish, now Austrian Netherlands. France withdrew from the conquered Breisgau, but kept Landau. The deposed electors of Cologne and Bavaria received their dignities back. Officially, he did not give up his claim to the Spanish throne, but de facto recognized the situation.

The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 enacted the indivisibility of the Habsburg lands as well as secondary female inheritance. Since Charles VI. Leopold's only male descendant died in 1716 as a small child, this case occurred after his death. The pragmatic sanction was more than a regulation of the succession. Rather, it aimed at a closer cohesion of the various Habsburg possessions. The document spoke of an inseparable union of the Habsburg lands. Between 1720 and 1724, the emperor had the pragmatic sanction confirmed by the various assemblies of the estates. This attempt to connect the individual countries of the Habsburg Monarchy more closely with one another was a further step towards the formation of a great power Austria. The emperor worked hard to get the pragmatic sanction recognized by the foreign powers.

Internal politics in the Habsburg states

In the implementation of his policy, Charles VI supported. experienced ministers and advisers such as Gundaker Thomas Starhemberg or Prinz Eugen. But this initially good relationship changed later. Interventions by the emperor in the financial system led to the withdrawal of Starhemberg for a time. A circle of Spanish emigrants, especially Johann Michael von Althann, had influence on the emperor . This side intrigued against Prince Eugene in 1719. This position could only be held with difficulty before he resigned from this office as governor-general in the Spanish Netherlands because of a lack of imperial support. Although he was still nominally President of the Secret Conference and the Court War Council , he largely lost influence. In the following, the emperor himself played a leading political role. Among other things, court chancellor Philipp Ludwig Wenzel von Sinzendorf supported him . The Paderborn Jesuit Vitus Georg Tönnemann became an important spiritual confidante and confessor . He was also a representative of the “Catholic Party” at court. Different views emerged among the ministers: While one group had Austrian interests in mind, the other - represented primarily by Imperial Vice Chancellor Friedrich Karl von Schönborn-Buchheim - emphasized the cause of the Holy Roman Empire.

A Spanish council for the government of the former Spanish possessions in Italy and a Dutch council for the Austrian Netherlands were formed. The Spanish Council also expressed the claim to the Spanish throne. The renaming to Italian Council in 1736 indicated a recognition of the realities. The peace years between 1720 and 1733 showed the emperor at the height of his power. However, the problems eventually led to a crisis in the empire.

Charles VI stopped the revision of the Renewed State Order of Bohemia ordered by Joseph I. 1712. However, a state committee was approved as the secretariat of the state parliament. The nobility received this confirmation of class rights positively. It was not until 1723 that he was crowned King of Bohemia in Prague. This was a conscious demonstration of power, also against the background of the policy of recatholization. Revolts by rural residents against the landowners led to several laws ("robot patents") by Charles VI.

At the beginning of his rule in Hungary was the end of the uprising of Francis II Rákóczi and thus the last Kuruc uprising . With the Pragmatic Sanction, Karl also pursued the goal of uniting Hungary inextricably with the other Habsburg areas. However, he had to make considerable concessions to the Hungarian nobility. The inherited rights and privileges were confirmed. The king also undertook to govern the country with the help of laws passed together with the assembly of estates. Although the king only called the meeting of the estates irregularly, the dualism of king and estates remained in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Settlement and minority policy

At the time of Charles VI. the settlement of peasants from Germany in parts of the countries of the Hungarian crown, some of which were depopulated by the wars, gained in importance. A first wave of settlement by the Danube Swabians took place between 1722 and 1727. In some cases, coercion was also used. In the course of the "Carolingian transmigration ", Protestant residents were resettled from the archbishopric of Salzburg to Transylvania . This group later called itself Landler .

Karl is considered to be one of the greatest enemies of Jews among the Habsburg rulers. Court factor Samson Wertheimer provided 148,000 guilders for his imperial coronation, the Jews had to pay 1,237,000 guilders (1717) for the costs of the fight against the Turks, and 600,000 guilders (1727) for the maintenance of the military. In 1732 the Viennese Jews offered the emperor support in vain by asking for permission to build a house of worship in the suburbs. In 1726, however, Karl issued the family laws for the crown lands of the monarchy , which limited the number of Jews and further restricted their freedom of movement. In 1738 he had all Jews expelled from Silesia. An expulsion of the Jews from Bohemia did not take place only because of the resistance of the estates to the feared trade damage. But he knew exceptions: In 1726 he raised the Marran Diego d'Aguilar to the nobility because he had organized the tobacco sales in Austria.

The Roma minority was persecuted by harsh means in both Austria and Hungary. In 1721 the emperor issued the order to arrest and "exterminate" all "gypsies" in the empire. In 1726 he ordered all male Roma in the area of today's Burgenland to be executed and an ear to be cut off from women and children under the age of 18. Many Roma fled but were also persecuted in other Habsburg areas.

Administrative, financial and economic policy

At the time of Joseph I and Charles VI. a clear separation began between court and state administration. But it was not possible to form an effective government from the coexistence of the various central authorities. The military organization was also not adapted to recent developments. The increasing age of Prince Eugene, who was responsible for the military, played a central role here. In contrast to Prussia, for example, the Austrian hereditary lands were at the time of Charles VI. economically, organizationally and militarily falling behind.

The emperor continued to rely on the approval of the estates for tax issues. Charles VI also intervened in the corporate structures. hardly undertaken. As a result of the ineffective administration and the high expenditure, the finances in particular were desolate. The debt grew from 60 to 100 million guilders during the reign. Between 1722 and 1726, Karl had the Carolinian tax cadastre set up in Silesia.

In Charles VI. During the reign, the economy was significantly promoted in the spirit of mercantilism . Commercial councils were set up in individual countries and a main commercial college in Vienna. Manufactories were founded in many places, and in some cases the road system was improved through the construction of commercial roads or imperial roads. Five art roads in a star shape led from Vienna to develop the empire. The internal tariffs were lifted and the postal system expanded. Settlers from the German-speaking area were also settled in other parts of the Habsburg states. A trade treaty with the Ottomans promoted Mediterranean trade. The ports of Trieste and Fiume were expanded and an oriental company was founded. Charles VI wanted the ports of the Spanish Netherlands. use as a basis for overseas trade, in addition to which the Ostend company was founded in 1722 . However, this competition worsened political relations with the northern sea powers. Ultimately, Charles VI. the Ostend Company to be able to enforce the Pragmatic Sanction internationally.

Imperial politics

For Joseph I as for Charles VI. In addition to strengthening the Habsburg hereditary lands, imperial politics also played an important role. They tried to influence imperial institutions such as the imperial chamber court or to use imperial knighthood as a means of enforcing imperial politics. Charles VI used imperial commissions to intervene, for example, in imperial city constitutional battles such as in Frankfurt am Main or Hamburg. The aim was to preserve the traditional structures and at the same time make it clear that the emperor was the actual head of the city. Charles VI also claimed a kind of imperial chief judge function in a religious controversy that sparked off in the politics of the Electorate of the Palatinate. An important element of imperial politics also under Charles VI. remained the Reichshofrat . During this time, among other things, the trials of the imperial estates of Mecklenburg against their sovereigns. In 1718, the Reich was executed and Duke Karl Leopold was deposed . In the similar case of East Friesland, the local sovereign got the right. After that, neither Franz I nor Joseph II pursued such an imperial policy related to the empire .

With regard to imperial politics, however, there were developments that made active imperial politics difficult. Some imperial estates such as Austria with Hungary and Italy, but also the electorate of Hanover, which was linked in personal union with Great Britain, and the strengthened Prussia grew out of the empire. Other imperial estates, such as Bavaria, also pursued independent and in some cases anti-imperial policies. The dispute between the Electoral Palatinate and Hanover over the honorary title of arch-treasurer blocked the Reichstag between 1717 and 1719. In the religious dispute in Electoral Palatinate, the emperor was unable to prevail against Hanover, Prussia and the other Protestant imperial estates. It is also significant that Hanover and Prussia refused to involve the Kaiser in the peace negotiations with Sweden to end the Northern War . In addition, other imperial estates sank to insignificance. Some, like the principalities in Anhalt, became Prussian client states. In southern Germany, the small imperial estates were mostly loyal to the emperor, without that for Charles VI. would have been associated with a significant increase in power. The research spoke for the time of Charles VI. from the beginning of "Reich fatigue" or the "seeping away of the Reich thought "

Foreign policy and wars

After the War of the Spanish Succession had clarified the situation in the West, the Emperor, on the advice of Prince Eugene, ordered the war against the Ottomans in support of Venice . Under the command of Prince Eugene, the Austrian troops were victorious in the Battle of Peterwardein in 1716 and in the Battle of Belgrade in 1717 in the Venetian-Austrian Turkish War . In the Peace of Passarowitz , concluded in 1718 , Charles VI won. the Banat , Belgrade and parts of Serbia as well as Little Wallachia . With this the Habsburg Empire reached its greatest territorial extent, reaching far beyond the borders of Hungary.

In Italy, Spain threatened Austria's supremacy in order to regain its lost territories. Spanish troops landed in Sardinia in 1717 and in Sicily in 1718. In contrast, a quadruple alliance was formed in which Great Britain, the Netherlands, France and Austria participated. This led to the war of the Quadruple Alliance . In the naval war, the Spanish were defeated by the British in the sea battle off Cape Passero . The emperor's army recaptured Sicily. In the end, Charles VI exchanged. Sardinia against Sicily. The island was united with Naples. The Spanish Prince Carlos received the entitlement to Parma, Piacenza and Tuscany. Nevertheless, the power of the Habsburgs in Italy was as strong as since Charles V not.

Contrary to the advice of Prince Eugene, the emperor was prepared to give up the alliances with Great Britain and the Netherlands. But hopes for an alliance with France were dashed. In 1725 peace was made with Spain and an alliance and trade treaty was concluded in the Treaty of Vienna . In return, Great Britain allied itself with France and Prussia in the alliance of Herrenhausen . The emperor's diplomats succeeded in detaching Prussia from the alliance, but a great war threatened, to which Charles VI. wasn't ready. Therefore he gave in to the question of the Ostend Company in 1727 and did not participate in the war between Spain and Great Britain . His alliance policy finally failed when Spain joined France and Great Britain in 1729.

Now the emperor found a balance with Prince Eugene. It is mainly due to him that good relations with Prussia and Russia developed during this time. The prince was also responsible for the 1731 reconciliation treaty with Great Britain. In it, Great Britain and the Electorate of Hanover associated with it recognized the pragmatic sanction. Denmark and various imperial estates were also won in secret negotiations, so that the Pragmatic Sanction was recognized by the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire .

In 1733 the War of the Polish Succession followed , which was not only about the succession in Poland. Because of the impending marriage of Maria Theresa to Franz Stephan of Lorraine, France feared a further strengthening of Austrian power. In alliance with Spain and Savoy , France attacked Austria in Italy. The war went badly for the Austrian side. In the meantime Johann Christoph Freiherr von Bartenstein had become the emperor's closest political advisor. In 1735, Bartenstein agreed a secret preliminary peace with France , which was later officially confirmed. In it, the emperor had to cede some areas in northern Italy to Savoy, but was able to maintain his position there. However, he had to cede Naples and Sicily and renounce the claim to Lorraine, which fell to France. Franz Stephan of Lorraine was resigned to the Duchy of Tuscany . In return, France also recognized the Pragmatic Sanction.

In 1737 Charles VI took part. in the Russian Turkish War . After a defeat, in the Peace of Belgrade in 1739, the areas south of the Danube and Save with Belgrade fell back to the Ottoman Empire.

At the death of Charles VI. Austria was humiliated and politically isolated. His successor Maria Theresa took on a difficult legacy, especially since it became clear that the Pragmatic Sanction did not protect against disputes over the Reich.

Promotion of art and culture

Like his father, the emperor was artistically versatile (he is considered one of the “composing emperors”) and particularly promoted musical culture. Under him, the court music band under Johann Joseph Fux experienced a heyday. He also promoted other areas of culture, in Vienna he brought together the imperial collection of paintings spread over various locations .

A high point of baroque art and thus one of the cultural high points of Austria fell in time. In 1713, after a year of plague, the emperor himself vowed to build the Karlskirche in Vienna, built by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach . He also acted as a builder in Klosterneuburg Abbey to transform it into a residence based on the model of the Escorial in Spain. He also had the Hofburg expanded. The Michaelertrakt, the Reich Chancellery and the Winter Riding School were built. Overall, the fortress character of the Hofburg changed to a palace.

Charles VI had the court library rebuilt and expanded its holdings by purchasing the library of the late Prince Eugene. The emperor's art policy also had political goals in that it followed an imperial program and consciously made use of the old imperial symbols.

The planned establishment of an Academy of Sciences did not materialize. In 1735 he founded the West Hungarian University in Ödenburg . He was also in correspondence with Leibniz , who came to Vienna in 1713. In terms of church politics, he obtained the elevation of the Diocese of Vienna to an Archdiocese.

death

Charles VI died on October 20, 1740 after a ten-day illness at the age of 55 in the Neue Favorita (now a public high school of the Theresian Academy Foundation ). On October 10th, he had eaten large quantities of a mushroom dish. The following day, he was plagued with severe nausea, vomiting, and episodes of unconsciousness. After a few days of recovery, the symptoms returned, accompanied by a high fever, and eventually led to his death.

The description of the symptoms and the circumstances of his death are typical of a poisoning with the green capillary mushroom and have been repeatedly interpreted as such, this ultimately remains speculative.

Charles VI was buried in Vienna according to the ritual customary in the 18th century in the House of Habsburg: his body rests in a sarcophagus in the Capuchin Crypt , his heart was buried separately and is located in the Loreto Chapel of the Vienna Augustinian Church , while his entrails in the ducal crypt of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna were buried. He is one of those 41 people who received a “ separate burial ” with the body being divided between all three traditional Viennese burial sites of the Habsburgs (Imperial Crypt, Heart Crypt, Ducal Crypt).

person

Charles VI himself was partly responsible for the decline in power in the last decades of his rule. Already in Spain, under the influence of Count Johann Michael Althann, he developed an almost anachronistic, universalistic understanding of rule that was linked to Charles V. Although he took care of state affairs intensively, he lacked an overview and ultimately a clear political line.

In his private life, the emperor led an exemplary family life and was a caring father. Like his father, he meticulously watched over court etiquette and personally over compliance with the existing rules at court. While still on his deathbed, he criticized those around him for allegedly not having enough candles around his bed. He found personal pleasure in hunting and in love. Due to his nearsightedness, however, he was a bad shot.

title

Emperor Karl's title as Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain read:

“We, Charles the Sixth, chosen by the grace of God, Roman Keyser, at all times several members of the empire, king in Germania, in Castile, Leon, Aragon, Beyder Sicily, in Hierusalem, Hungarn, Böheimb, Dalmatia, Croatia, Navarra, Toleto, Valencia , Gallicia, Majoricarum, Sevila, Sardinia, Corduba, Corsica, Murcia, Giennis, Algarbien, Algezirae, Gibraltaris, the Canariae and Indiarum Islands, the Eceani Islands and Terrae Firmae etc .; Archduke of Austria; Duke of Burgundy, Braband, Meyland, Steyer, Carinthia, Crain, Lüzelburg, Würtemberg, Upper and Lower Silesia, Athenarum and Neopatriae; Prince of Swabia; Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, Burgau, Moravia, Upper and Lower Lusatia; prince count of Habsburg, Flanders, Tyroll, Barchinon, Pfierd, Kyburg, Görtz, Rossilion and Ceritania; Landgrave in Alsace; Marggraf zu Oristani and Count zu Gocceani, and Gradiska; Herr on the Windischen Mark, to Portenau, Biscajae, Molini, to Salins, to Tripoli and to Macheln. "

Seal, signature and motto

The seal of Charles VI. from 1725 shows his coat of arms shield (with crown) and the crowned double-headed imperial eagle , which has seven large feathers on each wing (the number has not been specified anywhere), with the regalia: in his right claw he holds the imperial scepter and the imperial sword , in the left the imperial orb. An inscription with the title Charles VI forms the edge of the seal. in abbreviations and a wreath. The inside diameter of the seal is 13.5 cm.

It has the following text:

"CAROL VI. · DG · ROM: IMP: S · A · GER: HISP: HUNG: BOH: [ UTR : SIC]: HYER: ET INDIARŪ: RX · ARC: D · AUS · D: BURG: BRAB: MEDIOL · PR: SUEV: CATAL · MAR · S · R · I · COM: HABS · FL: TYR: "

This corresponds to:

"Carolus VI. Dei Gratia Romanorum Imperator semper Augustus Germaniae Hispaniae Hungariae Bohemiae utriusque Siciliae Hyerosolymis et Indiarum Rex, Archidux Austriae, Dux Burgundiae Brabantiae Mediolani Princeps Sueviae Catalaniae Marchio Sacri Romani Imperii Comes Habsburgi Flandriae Tyrolis "

In translation:

"Charles VI. By God's grace Roman emperors, at all times several of the empire, king of Germania, Spain, Hungary, Bohemia, both Sicily, Jerusalem, and the West Indies, archduke of Austria, duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Milan, prince in Swabia, Catalonia, margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, Count of Habsburg, Flanders, Tyrol "

Here it becomes clear again how Charles VI. could not yet fully accept the loss of Spain. However, in the Peace of Vienna (1725) he was granted the right to continue to use this title.

His motto was Constanter continet orbem (Latin for a festival that holds the empire together ).

ancestors

Honors

In 1899, Karlsplatz in Vienna- Wieden (4th district) was named after Emperor Karl.

literature

- Alfred von Arneth : Karl VI., Holy Roman Emperor . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 15, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1882, pp. 206-219.

- Max Braubach : Karl VI., Emperor. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 11, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-428-00192-3 , pp. 211-218 ( digitized version ).

- Hans-Josef Olszewsky: Karl VI. (HRR). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 3, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-035-2 , Sp. 1151-1157.

- Bernd Rill : Charles VI. Habsburg as a great Baroque power . Graz 1992, ISBN 3-222-12148-6 .

- Hans Schmidt : Charles VI. 1711-1740. In: Anton Schindling , Walter Ziegler (ed.): The Emperors of the Modern Age 1519–1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany . Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-34395-3 , pp. 200-214.

- Stefan Seitschek, Herbert Hutterer, Gerald Theimer (eds.): 300 years of Karl VI. 1711-1740. Traces of the rule of the “last” Habsburg . Accompanying volume for the exhibition. Austrian State Archives, Vienna 2011 ( online)

- Stefan Seitschek: The Diaries of Emperor Charles VI. Between melancholy and zeal for work . Horn 2018, ISBN 978-3850288569

- Claudia Michels: Carnival opera at the court of Emperor Charles VI. (1711-1740). Art between representation and amusement (= publications of the Institute for Austrian Music Documentation, Volume 41). Hollitzer, Vienna 2019, ISBN 978-3-99012-366-9

Web links

- Literature by and about Charles VI. in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Charles VI. in the German Digital Library

- Entry to Charles VI. in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Entry to Charles VI. in the database of the state's memory for the history of Lower Austria ( Museum Niederösterreich )

Individual evidence

- ^ Rill, Bernd, Karl VI. Habsburg as a baroque great power , Graz 1992, ISBN 3-222-12148-6

- ↑ mush, Franz, The art in the service of the idea of the state of Emperor Charles VI. Iconography, iconology and programming of the "imperial style" , 1st half-volume, Berlin, New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-008143-1 , p. 201.

- ↑ János Kalmár: Ancestors as role models. The later Kauser Karl VI. In his youth he wrote Canon of the Ruler's Virtues page 43 . Nobility in the "long" 18th century 14. In: Central Europe Studies . ISBN 978-3-7001-6759-4 ( Epub ÖAW ).

- ↑ a b Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck : The Army History Museum Vienna. Hall II - The 18th Century to 1790 , Salzburg 1983, p. 74.

- ^ A b Hans Schmidt: Karl VI. 1711-1740. In: The emperors of the modern age 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany, Munich 1990, p. 203.

- ^ Gerhard Hartmann / Karl Schnith (editor): Die Kaiser , ISBN 3-86539-074-9 , p. 587.

- ↑ Hans Schmidt: Karl VI. 1711-1740. In: The emperors of the modern age 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany. Munich 1990, p. 206.

- ↑ a b c Hans Schmidt: Karl VI. 1711-1740. In: The emperors of the modern age 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany , Munich 1990, p. 208.

- ↑ The coronation of Charles VI. in Prague

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch: History of Bohemia. From the Slavic conquest to the present, Munich 1997, p. 248f.

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch: History of Bohemia. From the Slavic conquest to the present , Munich 1997, p. 252.

- ↑ Ellen Blos: Constitution and system change. The institutionalization of democracy in post-socialist East Central Europe, Wiesbaden 2004, p. 215.

- ^ Hans Gehl: Dictionary of Danube Swabian Life Forms, Wiesbaden 2005, p. 24.

- ↑ cf.: Martin Bottesch (among others) (Ed.): The Transylvanian Landler. Vienna u. a., 2002.

- ↑ Austria Forum | https://austria-forum.org : Emperor Karl VI. - Patron of Faith at the Beginning of the Early Enlightenment in the Baroque Age. Retrieved April 9, 2020 .

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch: History of Bohemia. From the Slavic conquest to the present, Munich 1997, p. 258.

- ^ Mordechai Breuer , Michael Graetz: German-Jewish history in modern times. Volume 1: Tradition and Enlightenment 1600–1780. Beck, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-45941-2 , p. 148f.

- ↑ Ulrich Friedrich Opfermann : "That they take off the gypsy habit". The history of the "Gypsy colonies" between Wittgenstein and Westerwald. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-631-49625-7 , p. 25.

- ↑ Burgenland-roma.at

- ^ Bertrand Michael Buchmann: Court - Government - City Administration. Vienna as the seat of the Austrian central administration from the beginning to the fall of the monarchy . Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7028-0377-7 , p. 55.

- ↑ Heinz Duchhardt: Baroque and Enlightenment , Munich 2007, p. 104.

- ↑ Construction of the Kaiserstrasse

- ↑ a b Heinz Duchhardt: Barock and Enlightenment, Munich 2007, p. 103f.

- ^ A b Harm Klueting: The Empire and Austria 1648-1740. Münster 1999. p. 117.

- ↑ Hans Schmidt: Karl VI. 1711-1740. In: The emperors of the modern age 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany. Munich 1990, p. 207.

- ↑ Hans Schmidt: Karl VI. 1711-1740. In: The emperors of the modern age 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany, Munich 1990, p. 214.

- ^ Kunsthistorisches Museum: Reorganization under Emperor Karl VI.

- ^ Bertrand Michael Buchmann: Court - Government - City Administration. Vienna as the seat of the Austrian central administration from the beginning to the fall of the monarchy. Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7028-0377-7 , p. 59.

- ↑ Heinz Duchhardt: Baroque and Enlightenment, Munich 2007, p. 105.

- ^ William Coxe: "History of the House of Austria (London, 1807)" . Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ Robert Gordon Wasson: The death of Claudius, or mushrooms for murderers. Harvard University. Botanical Museum Leaflets. Vol 28, No. 8th 1972.

- ↑ Hans Schmidt: Karl VI. 1711-1740. In: The emperors of the modern age 1519-1918. Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Germany, Munich 1990, p. 200.

- ↑ The prince and his people praise and criticism of the rulers in the Habsburg lands of the early modern period. Colloquium at Saarland University 2002 edited by Pierre Béhar, Herbert Schneider, Wolfgang Brücher, Klaus M Girardet, Gerhard Sauder 2004 - p. 181

- ↑ June 3, 1815, source unknown, stated in: Franz Gall: Österreichische Wappenkunde. Böhlau, Vienna 1992; cited in Austria-Hungary: Apostolic King (Hungary), Habsburg Titles. In: Royal Styles. heraldica.org, January 18, 2007, accessed June 23, 2015 .

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Philip V. |

Duke of Milan 1706–1740 |

Maria Theresa |

| Joseph I. |

Roman-German Emperor 1711–1740 |

Charles VII |

| Joseph I. |

King and Elector of Bohemia 1711–1740 |

Charles III |

| Joseph I. |

King of Hungary , Croatia and Slavonia 1711–1740 |

Maria Theresa |

| Joseph I. |

Archduke of Austria 1711–1740 |

Maria Theresa |

| Philip IV |

King of Naples 1713–1735 |

Charles IV |

| Philip IV |

King of Sardinia 1713–1720 |

Viktor Amadeus |

| Maximilian Emanuel |

Duke of Luxembourg 1714–1740 |

Maria Theresa |

| Viktor Amadeus |

King of Sicily 1720–1735 |

Charles IV |

| Charles I. |

Duke of Parma 1735-1740 |

Maria Theresa |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Charles VI |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia and Hungary |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 1, 1685 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 20, 1740 |

| Place of death | Vienna |