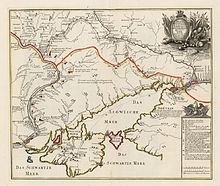

Russo-Austrian Turkish War (1736–1739)

The Russian-Austrian Turkish War (1736-1739; also the fifth Russian Turkish war or seventh Austrian Turkish war ) was a battle of the Russian empress allied Austria - Habsburg Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire against the Ottoman Empire , which, firstly, to Russian expansion to the Black Sea , on the other hand about Habsburg conquests in the Balkans . The conflict is therefore part of a long chain of ongoing Turkish wars . The official outbreak of the war was preceded by a number of skirmishes and punitive expeditions in the Khanate of Crimea in 1735 , which is why the literature occasionally gives the year the war began as 1735.

prehistory

The Russian Empire under Empress Anna (1693-1740) continued to pursue the strategic goals of Peter the Great (1672-1725) in the 1730s , which consisted of extending the borders of the empire to the coasts of the Black Sea , albeit from vassal states of the Ottoman Empire . It was hoped that this would give a share of the rich Black Sea and Mediterranean trade . When it came to warlike entanglements between the Ottoman Empire and the Persians (1731–1736) in Asia , the Russian side discovered a favorable opportunity to attack. This decision was favored by the prevailing view of the leading Russian ministers ( Biron , Ostermann , Münnich ) that the Ottoman Empire was close to collapse. The immediate pretext was the occasional incursions of the Crimean Tatars into the Russian border areas in 1735 , whereupon hostilities began the following spring.

For the Habsburgs with their Roman-German Emperor , the situation was different. After the Venetian-Austrian Turkish War (1714–1718), they had conquered the Banat and Belgrade from the Ottomans in the Peace of Passarowitz . But in the War of the Polish Succession (1733-1735 / 1738) they had to accept major territorial losses, especially in Italy. Emperor Charles VI. therefore hoped to conquer new countries in a new war against the Ottoman Empire in order to compensate for the previous losses. A second reason was that they wanted to prevent the tsarist empire from expanding too far in the Balkans. As justification for its entry into the war in 1737 he used an alliance with Russia from 1726, which during the crisis around the English-Spanish war had arisen (1727-1729), and it undertook to Russia in case of war with at least 30,000 imperial soldiers to support. In addition, during the War of the Polish Succession, Russian troops had moved to the Rhine in support of the emperor, which they now wanted to repay.

Military history

Campaign 1736

Ukraine - The campaign plan of the Russian Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Burkhard Christoph von Münnich (1683–1767) envisaged first conquering the Azov fortress with a corps and at the same time advancing with the main army on the Crimea . This was protected by a strong line of fortifications on the Isthmus of Perekop . On May 28, the main Russian army (approx. 54,000 men) under Field Marshal Münnich stormed this line and took the city itself. After he had sent part of his army (13,000 men) under General Leontjew to take Kinburn , he advanced with the rest of his troops on the Crimean peninsula. Bakhchysarai , the seat of the Khans of the Crimean Tatars, as well as the entire peninsula were devastated before Münnich withdrew to Ukraine due to supply problems and illnesses in his army. Count Peter von Lacy (1678–1751) had meanwhile conquered Azov with his corps (approx. 15,000 men) on July 4th, and General Leontjew had also taken Kinburn without difficulty. There had been no major battles, but due to disease and the constant guerrilla warfare of the Crimean Tatars, the Russian army had lost almost 30,000 men.

Campaigns in 1737

Ukraine - Already at the end of April the Russian main army (approx. 65,000 men) under Field Marshal Münnich crossed the Dnieper and marched to the fortress of Ochakov , which was defended by 20,000 Ottomans. On July 10th, Münnich reached the city and immediately opened fire. Without a formal siege, it was possible to take the fortress by storm. The Russians then repaired the fort's defenses. Münnich and the army moved to the Bug to cover Ochakov from there. There were only minor skirmishes until Münnich retired to winter quarters at the end of August. At the end of October a 40,000-strong army of the Ottomans and Tatars under the Seraski Ali Pasha and the Khan of the Crimean Tatars appeared in front of the fortress of Ochakov and tried to storm it. When this failed, however, the Ottomans had to withdraw again. Count Lacy had meanwhile operated with a second army (about 40,000 men) on the Don and the Sea of Azov against the Crimea. In July he managed to break into the Crimea again, from which he had to withdraw in August.

Balkans - On July 12, imperial troops (80,000 men; 36,000 horses; 50,000 militias ) crossed the borders of the Ottoman Empire, initially under the command of Franz Stephan von Lothringen (1708–1765), the husband of Maria Theresa (1717–1780). The main army under Field Marshal Friedrich Heinrich von Seckendorff (1673–1763) occupied Nisch at the beginning of August , a smaller corps under Field Marshal Georg Olivier Count Wallis (1673–1744) occupied part of Wallachia and another corps under the command of Prince Josef von Hildburghausen (1702–1787) besieged Banja Luka . However, the latter corps had to retreat behind the Save after a lost battle on August 4th in front of an Ottoman overwhelming power . From the main army a unit under Ludwig Andreas von Khevenhüller (1683-1744) was sent out to take Vidin . But the garrison of the fortress was reinforced and so the unit withdrew across the Danube after the battle of Radojevatz (September 28, 1737) near Orsova . There it united with the corps of Count Wallis, who had evacuated Wallachia because he believed that he would no longer be able to maintain it after the imperial troops had withdrawn from Timok (near Vidin). The main army had meanwhile moved west and taken the mountain fortress Užice and started the siege of Zvornik . With this march on the Drina , the loss of Nisch to an Ottoman siege army and Khevenhüller's retreat from Timok, the lines of communication through the Morava valley to the Austrian heartlands were lost. Thus the imperial troops withdrew from Serbia at the end of the year .

Campaigns in 1738

Ukraine - Field Marshal Münnich was to operate with the 50,000-strong main army on the Dniester with the aim of taking Bender or Chotyn . The army crossed the Dnieper in May and reached the Bug in June . The Ottoman and Russian armies watched each other on this river all summer long, so that there were only a few major battles (July 11th and 19th). Lack of food and illnesses induced Münnich to return to Ukraine in September and move into winter quarters. Lacy, who in turn was to advance against the Crimea with 35,000 men in order to take the city of Caffa , captured Perekop in July and broke into the peninsula again. On July 20, he defeated the Ottomans in a major battle, but since the Crimea was too devastated by the devastation of recent years, the Russian troops could not hold out there. At the end of August they cleared the peninsula. The fortress of Ochakov had to be given up again this year without a fight.

Balkans - Count Joseph Lothar von Königsegg-Rothenfels (1673-1751), the President of the Court War Council, took over the command of the army, even if Duke Franz returned to the army in the summer. The German imperial army was now on the defensive. In previous years, the Ottoman army had been reformed by Count Claude Alexandre de Bonneval (1675–1747), among others , and had gained in clout. With the help of the improved artillery , the Ottomans took back the Serbian fortresses step by step. In May they invaded the Banat and occupied Mehadia . In the following, the fighting concentrated on the smaller Danube fortresses. Königsegg initially gained some advantages at Ratza and Pancsova , but by the end of the year the Ottomans had conquered Mehadia, Orșova , Ada Kaleh , Semendria and Utschitza . In this campaign, Kurdish regiments also took part to a large extent , which the emperor had requested as auxiliary troops.

Campaigns in 1739

Ukraine - Field Marshal Münnich gathered the main army (57,000 men, 180 guns) in May and led them over Polish territory to the Dniester. On July 10th this army crossed the Bug. In contrast, the Ottoman army gathered under Beli Pasha at Bender. Münnich first tried to conquer Chotyn , but on the way there came surprisingly against the Ottoman army. In the Battle of Stavutschan , the Russians defeated the Ottoman forces on August 27. The city of Chotyn fell a short time later. Since there was no longer an Ottoman army in the field, Münnich's army advanced unhindered over the Prut to Jassy and Buschatsch at the beginning of September before they went into winter quarters. There Münnich received the news of the concluded peace treaty.

Balkans - With Count Wallis, there was another change in commander-in-chief of the approximately 60,000-strong army on the imperial side at the beginning of the campaign. With most of the armed forces he crossed the Danube at Pancsova and moved south. On July 22nd, he met the main Ottoman power in the Battle of Grocka and suffered a heavy defeat. Valais then withdrew across the Danube with constant fighting (battle near Pancsova on July 30th), while the Ottomans began to siege Belgrade. This siege was already accompanied by intensive negotiations, which finally led to the preliminary peace on September 1st . This was seen as treason by the much more successful ally Russia.

Peace treaty and consequences

The mediation between the warring parties was organized by French diplomats, who traditionally had good relations with the Porte . France's goal was to detach the emperor from the alliance with Russia and at the same time to strengthen his own influence in the Ottoman Empire. The readiness of all three warring parties was great. The Ottomans had suffered heavy losses and defeats against the Russians. The German Kaiser had also suffered defeats and was facing the loss of Belgrade. The Russian Empire saw itself threatened by the renewed armament of Sweden and wanted to be able to move its army to the north soon.

On September 18, 1739, the German Emperor and the Ottoman Empire concluded the Peace of Belgrade . The Habsburg monarchy had to cede Little Wallachia (in today's Romania ) as well as northern Serbia with Belgrade and a border strip in northern Bosnia to the Ottoman Empire and thus lost most of its acquisitions from the Peace of Passarowitz of July 21, 1718; all that remained was the Temesvar Banat .

Thereupon it was believed that peace had to be made at the Russian imperial court and the French diplomats were given full powers. Accession to the Peace of Belgrade was of little benefit to Empress Anna . She renounced all territorial conquests. Only the Azov Fortress (whose works had to be razed) and the city of Zaporizhia fell to Russia. As a result of the war, the Porte severely curtailed the rights of Russian traders in the Black Sea in the years that followed. In May 1740, however, the French trade privileges were expanded by being the only foreigner in the Ottoman Empire to be exempt from import duties.

literature

- Georg Heinrich von Berenhorst : considerations on the art of war. Volume 3, Leipzig 1799.

- Carl von Clausewitz : Field Marshal Münnich. In: Left work of General Carl von Clausewitz. Volume 9, Berlin 1837, pp. 15-28

- Bernhard von Poten (Ed.): Concise dictionary of the entire military sciences. Volume 9, Leipzig 1880.

- Melchior Vischer : Münnich - general, engineer, traitor. Frankfurt / Main 1938.

- Heinz Duchhardt : Balance of Powers and Pentarchy - International Relations 1700–1785. Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 1997. (= Handbook of the History of International Relations, Volume 4)

- Ferenc Majoros and Bernd Rill: The Ottoman Empire 1300–1922. Augsburg 2002.

- Hans-Joachim Böttcher : The Turkish Wars in the Mirror of Saxon Biographies . Gabriele Schäfer Verlag, Herne 2019, ISBN 978-3-944487-63-2 .