Crimea

| Crimea | |

Satellite image of the Crimean peninsula |

|

| Geographical location | |

| Coordinates | 45 ° 21 ′ N , 34 ° 19 ′ E |

| location | Southern Ukraine |

| Waters 1 | Black Sea |

| Waters 2 | Sea of Azov |

| length | 200 km |

| width | 325 km |

| surface | 26,844 km² |

The Crimea ( Ukrainian Крим , Krym; Russian Крым , Krym ; Crimean Tatar Qırım ; in ancient times Tauris ) is a peninsula of Ukraine between the northern Black Sea and the Sea of Azov . The Crimea has an area of 26,844 square kilometers and 2,353,100 inhabitants (January 1, 2014).

There is no longer an indigenous population according to modern categories . The Crimea was once inhabited by Taurians and Cimmerians . At the same time as the Greeks , the Scythians advanced into the Crimea. Later, the area was under Roman , Gothic , Sarmatian , Byzantine , Hunnic , Khazar , Cypchak , Mongolian - Tatar , Venetian , Genoese and Ottoman rule and finally became part of the Russian Empire at the end of the 18th century . After the Russian Civil War , it became part of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic within the Soviet Union (USSR), was fought over during World War II and was temporarily occupied by the Wehrmacht . After the reconquest by the Red Army in 1944, mass deportations of non-Russian ethnic groups under Stalin followed. In 1954, under Khrushchev, Crimea was annexed to the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic and, after the dissolution of the USSR, remained within the Ukrainian state as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea .

Since the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014 in the course of the Crimean crisis , the international legal affiliation of the peninsula has been controversial. Russia, which has exercised de facto control over Crimea since then, sees it as two of its federal subjects (at times also as a federal district of its own ), while Ukraine and the vast majority of the international community continue to regard Crimea as an autonomous republic of Crimea and part of the Ukrainian national territory .

geography

Relief map with the largest cities of the Crimea |

The Crimea is the largest peninsula in the Black Sea . It is surrounded to the west and south by the Black Sea and to the east by the Sea of Azov . In the north, the peninsula is connected to the mainland by the Sywasch , a large system of flat bays in the west of the Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop provides a continuous land connection to the Ukrainian mainland. In the east, the Crimea borders with the Kerch Peninsula on the Kerch Strait , on the opposite bank of which lies the Taman Peninsula, which belongs to the Russian Krasnodar region .

The northern part of the peninsula is flat to gently undulating and forms a steppe landscape that was irrigated with water from the Dnieper via the North Crimean Canal until the annexation of the Crimea .

In the south of the peninsula lies the Crimean Mountains , which are not only a geographical obstacle, but also a weather and climate divide . While more moderate climatic conditions prevail north of the mountains and especially the winters are significantly colder, south of the Crimean Mountains there is a Mediterranean climate in which tropical fruits and vines thrive.

The highest peaks of the Crimean Mountains are the Roman Kosch ( 1545 m ), the Chatyr-Dag ( 1527 m ) and the Lapata ( 1406 m ). Numerous rivers form here, such as the Alma , Belbek , Tschorna and the two source rivers of the Salhyr , the longest river in Crimea at 232 kilometers. The Uchan-Su waterfall is the highest waterfall in the Crimean Mountains.

Another special feature is the Arabat Spit , which separates the Sea of Azov from the Sywasch. The spit lies between the city of Henichesk, Ukraine, in the north and the northeast coast of the Crimean peninsula in the south. The Arabat Spit is 112 km long and 270 m to 8 km wide. Its area is 395 km², the average width is 3.5 km.

Etymology of the name

The name of the Crimea is possibly derived from the Mongolian- Tatar kerim "fortress" or from the Crimean Tatar qrım "rock" , but possibly also from the ancient people of the Cimmerians who lived in the Crimea and are mentioned by ancient Greek authors. It is likely that the name Crimea once referred to the region in the mountainous south of the peninsula. This extended over the hinterland between the Bay of Sevastopol (historic Chersonese ) and Sudak (formerly also called Soldaiam ). Forty fortified settlements ( castra, castella ) are said to have been there in the Middle Ages . The Turkic origin of the name Qirɨm was therefore also derived from Qirq-ïer , i.e. i. qirq "forty" + ïer "places". The Flemish Franciscan Willem Ruysbroek reported on this importance of “forty localities” in 1253: “ sunt quadraginta castella inter Kersonam et Soldaiam ”. The Kurdish chronicler and geographer Abu'l-Fida reported in 1321: " Qirim is the name of a region that contains about forty villages, of which Sūdāq and Kafā [today's city of Feodosiya] are among the most famous."

history

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

In the Crimean Mountains, at the Kiik-Koba site , the first Neanderthals were discovered in Eastern Europe in 1924 and dated to an age of around 73,000 years.

In ancient times, the Crimea was initially inhabited by Cimmerians and Taurians . When the Greeks began to found cities , they came across Scythians who lived in the late 8th century BC. Immigrated to the northern Black Sea area. For the Greeks, the Crimea was of interest as a commercial contact with regions rich in grain. The Bosporan Empire developed from the cities . The Greeks gave the peninsula the name Chersónesos Tauriké (Taurian Peninsula) after the local Taurean tribe. The most important city was called Chersonesos , a Greek polis on the outskirts of today's Sevastopol (for the Greek colonization, see there).

In the 1st century BC Like all parts of the Greek world, Crimea came under Roman influence, but was not organized as a Roman province. The Bosporan Empire continued to exist, as did the nominally independent Greek Polis Chersonesos. In the 3rd century AD, Goths appeared in the Crimea in the run-up to the so-called mass migration (although today it is disputed whether this people actually immigrated or whether they were formed here through ethnogenesis ). Some of the Crimean Goths can be traced back to the 16th century. They gave the region its name, which the Italians called Gotia , until the 15th century . From the 5th century onwards, they were first followed by the European Huns , followed by the Khazars , Cumans and Tatars in the early Middle Ages . In the Middle Ages, the name Khazarian Peninsula or Gazaria was common for the region. After the destruction of the Khazar Empire by Svyatoslav I , the Crimean cities of Kerch and temporarily Sudak belonged to the old Russian principality of Tmutarakan between the 10th and 12th centuries , the center of which was on the Taman Peninsula.

In the 13th century the Mongols of the Golden Horde , to whose sphere of influence the peninsula belonged at that time, had extensive trade relations. Trade via the Crimea to Egypt was particularly pronounced and can only be compared with the trade relations between the Mongols and the Italians, in this case Genoa and Venice in particular . These often acted as middlemen and transporters of trade to Egypt. One of the main trade goods on this route were slaves , while in the direction of Europe, besides these, mainly grain, spices and fur products were exported. The basis for this great economic role of the Crimea was the strategically favorable position near the northern end of the Silk Road ("Mongolian route"). Only the Venetian-controlled port of Tana on the Don Estuary presented serious competition for the Crimean port cities .

The political history of Crimea in the late Middle Ages is shaped by the disputes and competitive struggles between the various Christian powers (Genoa, Venice, Byzantium ) and the often problematic relationships between them and the Golden Horde or the expanding Ottoman Empire , in whose hands the Crimea was The course of the 15th century finally fell completely. The Italians, who had dominated the trade until then, were deported to Constantinople and Pera .

Crimean Tatar Khanate

In the course of the disintegration of the Golden Horde, the Crimean Khanate arose in the Crimea around 1430 under the rule of a branch line of the Mongol Khanate with the capital Bakhchysarai , which brought large parts of today's Ukraine under its control. It fell under Ottoman control as early as 1475, but retained a certain degree of autonomy. In 1502, the Crimean Tatars defeated the last Khan of the Golden Horde, which promoted the Russian conquest of Kazan (1552) and Astrakhan (1556). The Crimean Tatars made frequent raids into the interior of Ukraine and Russia, and took many prisoners who they sold as slaves to the Orient. In 1571 they penetrated as far as Moscow and set it on fire, but were defeated the following year in the Battle of Molodi . The Crimean Khanate took part in numerous military conflicts in Eastern and Central Europe. The constant danger emanating from the steppe riders forced Russia to maintain an elaborate and expensive line of spoils for many years in order to defend itself against the Tatars - also with the help of the Cossacks . Among the first Russian attempts to penetrate the Crimea were the Crimean campaigns during the reign of Sofia Alexejewna . In the Russo-Austrian Turkish War , Field Marshal General Burkhard Christoph von Münnich , of German descent, devastated the Crimea for the first time in 1736 in the service of Empress Anna .

Russian Empire

Until the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) , the Crimean Khanate was a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. With the help of the Russian Empire , the detachment was achieved, the Ottomans had to recognize the "independence" of Crimea in the peace treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774, but this was followed by a creeping Russification . Many Crimean Tatars fled to what is now Turkey . Under Grigori Potjomkin , the state of the Crimean Tatars finally came under Russian rule through annexation : On April 8, 1783, the Crimea was formally declared as Russian by Catherine II "from now on and for all time". However, this was not recognized by the Ottoman Empire until the Treaty of Jassy on January 6, 1792. Administratively, the Crimea was subordinate to the Taurian Governorate ( Russian Таврическая губерния ), which also included part of the eastern mainland coast to the lower Dnieper . " Taurien " was supposed to be established as the new name of the Crimea, but did not catch on.

After the incorporation, colonists were recruited, including Germans , Italians , Greeks, Bulgarians, Balts and Russians. The latter were mostly discharged soldiers or Zaporozhian Cossacks . The Tatar peasants, who made up 96 percent of the Tatar population, were pushed back into the sterile areas of the interior of the Crimea. Large parts of the fertile areas were distributed to squires from 1784 under Potjomkin's leadership. As a result of this policy, the Tatars moved more and more into the Ottoman Empire, and a total of 100,000 people left the Crimea.

In the first half of the 19th century, Sevastopol was developed into the main base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet under the direction of Admiral Mikhail Lazarev . From 1853 to 1856, the Crimea, and especially Sevastopol, were the scene of the Crimean War . Parts of the peninsula were temporarily occupied by Allied troops (France and Great Britain on the side of the Ottoman Empire, from 1855 still the Kingdom of Sardinia ). During and after the Crimean War there was another mass exodus. The Turkic people of the Tatars traditionally sympathized with the Ottoman Empire and feared further reprisals by the Russians. Further waves of emigration followed in the 1870s and 1880s, so that by the end of the 19th century the Tatars only represented a minority of around 187,000 people in the Crimea.

On October 29, 1914, Sevastopol was shelled by German warships flying the Turkish flag. This attack (as well as that on Odessa ) led Russia to enter the war against the Ottoman Empire. In December 1917, after the October Revolution in Crimea, the Crimean Tatars proclaimed the People's Republic of Crimea , the first attempt at a secular democratic order in the Islamic world. It was crushed by the Bolsheviks in January 1918 and replaced by the Tauride Soviet Socialist Republic (Russian: Советская Социалистическая Республика Тавриды). This only lasted a few weeks until troops from the Ukrainian People's Republic marched into Crimea.

Between the wars and the Second World War

During the Russian Civil War , the White Guards occupied the Crimea. After Wrangel's defeat , the Red Army invaded and in 1921 Crimea was proclaimed an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic ( ASSR ) within Soviet Russia . It thus remained administratively separate from the mainland, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic .

Shortly after the start of the German-Soviet War , on July 18, 1941 , Stalin ordered the expulsion of almost 53,000 Crimean Germans "for ever" in order to prevent their feared collaboration with the invaders. In a hurry, they had to pack up the bare essentials and were mainly transported to Kazakhstan , crammed into cattle wagons . Many died from the rigors of the days of driving.

The Crimea was occupied by the Wehrmacht from 1941 to 1944 after fierce fighting for Sevastopol . From December 11, 1941, Einsatzgruppe D of the Security Police and SD in cooperation with Wehrmacht units and others murdered . a. Almost the entire Jewish population of Crimea in the Simferopol massacre or in the Feodosia massacre : long-established Crimean chaks , Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim , the Karaites were supposed to be spared, but were also often victims of the Holocaust in Crimea . With reference to the Germanic Crimean Goths , the Crimea was to be annexed as Gotengau and colonized with South Tyroleans (see option in South Tyrol ), which however did not occur due to the course of the war. Thousands of Soviet soldiers and civilians offered bitter resistance against the Wehrmacht in the Adschimuschkai catacombs until late autumn 1942 .

After the Battle of Crimea , on May 18, 1944, on Stalin's orders, almost all Crimean Tatars still alive in Crimea towards the end of the war , 187–194,000 people, were deported to Central Asia by NKVD units on the blanket accusation of collaboration with Nazi Germany . Significantly more Crimean Tatars had fought as soldiers of the Red Army or as partisans in the Crimea against the Wehrmacht and the SS than had collaborated. About 7,900 people died during the deportation in cattle wagons , immediately after arrival in Central Asia another 16,000 died according to NKVD files, the proportion of the total victims until the end of the great Soviet post-war famine in 1946/47 is given as 15-27%, of Crimean Tatars Associations estimated at 46%. They were followed by 14,500 Greeks , 12,000 Bulgarians , 11,300 Crime Menians and around 2,000 Crime Italians . The monument “against cruelty and violence” at the Kerch train station commemorates the mass deportation of Crimean Germans, Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Bulgarians and Armenians . The Italians who had lived in Kerch since 1820 were forgotten. Stalin abolished Crimea's autonomy within the Soviet Union. In Crimea the crucial place in February 1945 Yalta conference of the Allies of World War II held before the end.

post war period

For eight years after 1946, Crimea was initially an oblast within the Russian Federative Socialist Soviet Republic (RSFSR). The living conditions of the population in Crimea, halved in comparison to the pre-war period, were poor. Soldiers of fortune with a criminal background moved into the area. The administrative subordination to the administration of nearby Ukraine should defuse this problem.

After Nikita Khrushchev became the Soviet party leader, the Crimea was annexed to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1954 . The occasion was the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Perejaslaw of 1654, under which the Ukrainian Cossack state, oppressed by Poland, had placed itself under the protection of the Russian tsar. According to the official Russian point of view (including that of the former Ukrainian Prime Minister Azarov), Nikita S. Khrushchev broke the constitution of the Russian Federation (RSFSR), which obliged the territorial integrity of the fatherland to be preserved. Actually, the Supreme Soviet in Moscow and that in Kiev should have agreed. But there was only one vote by their executive committees, and they were understaffed too, i.e. not formally legitimized. The 1st Secretary of the CPSU in Crimea, Pavel Titov, protested and was then replaced by Dmytro Polianski.

Nikita Khrushchev's son, Sergei Khrushchev , a space engineer and political scientist living in the USA , believes that the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine was made for purely economic, not political, moral or ethnic reasons. At the time, shipping canals from the Volga to the Crimea and the Donets Basin were planned, and it was more wise to plan to deal with these projects only in one instead of two Soviet republics (the Russian Federation and the Ukrainian Republic). For Nikita Khrushchev it was inconceivable that the Soviet Union could ever break up and that a state border could run between Russia and Ukraine.

In 1967 the Crimean Tatars were officially rehabilitated, ten years later than the other deported peoples. They were only allowed to return to the Crimea from 1988.

Secession from the Soviet Union

On January 20, 1991, 93 percent of Crimean residents voted in a referendum for the “re-establishment of the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Crimea (ASSK) as a subject of the USSR and a participant in the Union Treaty”.

The Supreme Soviet of Ukraine confirmed the establishment of an ASSK in a decision on February 12, 1991, but announced the "re-establishment of the ASSK as part of the Ukrainian SSR". However, an ASSK construct had never previously existed within a Ukrainian SSR, so that the decision was legally flawed. However, it was incorporated into the ASSK constitution on June 6, 1991, and made legally valid.

The Ukrainian SSR then declared itself independent on August 24, 1991 within the existing borders, including the Crimea. In the following referendum on the independence of Ukraine in December 1991, 54 percent of voters in the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of Crimea voted “Yes”. At first, Kiev was only able to assert its rule over the Crimea with difficulty. Only with considerable political pressure could a referendum on the independence of Crimea be prevented. As a compromise, in 1992 the region was declared an Autonomous Republic of Crimea within the Ukrainian state. She received sovereign rights in finance, administration and law. The 1998 Constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea established Ukrainian, Russian and Crimean Tatar as languages.

In the “ Budapest Memorandum ” of December 5, 1994, within the framework of the CSCE conference taking place in Budapest , Russia, Great Britain and the United States made three separate declarations each to Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus, in return for renouncing nuclear weapons to respect the existing borders of the countries (Art. 1) as well as their political and economic independence (Art. 2 f.) and, in the event of a nuclear attack on the countries, to initiate immediate measures by the UN Security Council (Art. 4).

With the independence of Ukraine, there was a dispute with the Russian Federation over the Black Sea Fleet and its home port of Sevastopol . In addition to its importance as an important naval base of the former Soviet Union, the city is also a national symbol , including a. because of their role in the Crimean War and World War II. In July 1993 the Russian parliament declared Sevastopol a Russian city on foreign territory modeled on Gibraltar . Only the contract of May 1997 regulated the division of the fleet and the whereabouts of the Russian Navy in the Crimea until 2017, which eased the situation. Russia leased the greater part of Sevastopol for twenty years. In the armed conflict between Georgia and Russia in 2008 , Ukraine, under the then President Viktor Yushchenko , sided with Georgia and threatened not to extend the stationing agreement with Russia. This happened in 2010 under President Viktor Yanukovych , who extended the lease until 2042. In return, Russia promised Ukraine reduced gas supplies. The ships of the Russian Black Sea Fleet were moored in the port of Sevastopol alongside those of the Ukrainian fleet. At the beginning of 2014, Russia increased the number of soldiers stationed in Crimea.

Crimean crisis and annexation by Russia

When Georgia’s membership of NATO was being discussed in 2008, US reports said Putin spoke in the NATO-Russia Council that if Ukraine joined NATO, Crimea and eastern Ukraine could be detached from Ukraine and annexed to Russia . After the political uncertainty in Ukraine in the wake of the Euromaidan , separatist efforts resurrected in February 2014 , with the help of Russian agitators. After armed forces occupied the regional parliament at the end of February , they cordoned off the building and only allowed a selection of MPs - invited by Sergei Aksyonov - to enter the building. It is unclear how many Aksyonov MPs were admitted to the session. In a closed session, Aksyonov was elected as the new Prime Minister and a referendum was held on the secession of Crimea from Ukraine and later the establishment of the Crimean Republic . Armed forces were in the wings of the building during this session.

The majority of the split-offs and referendums are not recognized at the international level. In Germany , Austria and Switzerland , the term annexation is predominantly used in public presentation . In exceptional cases, the term secession is used as an argument.

In the referendum on March 16, 2014 on the status of Crimea , with a turnout of 83.1% according to the official final result, 96.77% of the voters were in favor of joining Russia. According to a report by the Human Rights Council to the Russian President published at the end of April 2014, however, "[n] oh different information [...] 50 to 60% of the voters voted for the connection, with a voter turnout of 30 to 50%." around a small delegation of human rights activists known as opposition such as Svetlana Gannushkina , whose survey methods were not described in detail.

On March 18, the Russian President , Vladimir Putin , informed the public about the application of the Republic of Crimea to join the Russian Federation . On the same day, Putin, together with the Prime Minister of the Republic of Crimea Sergei Aksyonov , the parliamentary chairman Vladimir Konstantinov and the chairman of the coordination council for the organization of the city administration of Sevastopol, Alexei Chaly , signed an accession treaty for Crimea to join Russia and announced that there would be two new federal subjects give.

After the ratification of the treaty by the Russian Duma and the Russian Federation Council, and after the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation had declared the legality of the integration treaty between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Crimea, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the constitution-amending law on March 21, 2014 Crimea as federal subjects Republic of Crimea and city of federal rank Sevastopol in the Russian Federation. The prevailing opinion of international law is annexation. The Russian public representation speaks of a (re) unification of Crimea with Russia (воссоединение, присоединение), referring to the right to self-determination enshrined in international law . In a resolution of March 24, 2014, which is not binding under international law, an absolute majority of 100 states in the UN General Assembly , of which 193 member states belong, declared the referendum in Crimea to be invalid. 58 states abstained and eleven voted against the resolution, including Syria , North Korea and Cuba . The West was of the opinion that Russia had engaged in aggressive lobbying against the resolution and that the number of yes votes was surprisingly high afterwards. For its part, Russia had accused the West of “economic pressure and blackmailing numerous states” in the vote.

Crimean Tatars and Ukrainian activists had been calling for the Crimea's power supply to be cut off for months while the supply was still going through Ukraine. When electricity pylons were blown up in Cherson Oblast in the nights of November 20 and 22, 2015, when several essential overhead lines just north of the Crimea were interrupted by the electricity supply from Ukraine, a state of emergency was declared due to a lack of electricity. Around 100 km of high-voltage lines had been built since the annexation of Crimea. On December 31, 2015 it was reported that the only repaired power supply line from Ukraine was interrupted again due to wind or blasting and that - despite the new submarine cable from Russia - Crimea could only be supplied with electricity by the hour. On May 11, 2016, President Putin activated the fourth and last part of the Russian power line to Crimea, which supplies the peninsula with electricity from Russian power plants. The Crimea also received special funding from the federal budget; In 2017 the city of Sevastopol alone received the equivalent of 68 million euros from the central budget.

By admitting Crimea, Russia violated its own constitution. The Russian Duma elections on September 18, 2016 in Crimea had been described as illegal by Western countries; Crimean Tatar activists called for a boycott.

population

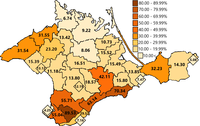

Around 2.35 million people live in Crimea, around 386,000 of them in Sevastopol , the largest city on the peninsula. About 60% are Russians, 25% of the population are Ukrainians. The proportion of the ethnically Russian population has been falling slightly for years in both the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol. The proportion of Ukrainians is only falling in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, while it is rising slightly in Sevastopol. The proportion of Crimean Tatars has increased significantly since 1989 when they returned from exile. It is currently around 12%. Based on the Crimean Tatars, Crimea is a center of Islam in Ukraine . After their return, the Tatars were no longer allowed to settle on their previous properties, as Stalin left them to the predominantly Russian colonists. Because of this, the current distribution of Crimean Tatars differs greatly from that of the prewar period. In addition, only about half of the Crimean Tatars returned from exile in Uzbekistan .

According to Amnesty International , Human Rights Watch and the NGO Society for Threatened Peoples , the Crimean Tatars under the Russian administration were victims of human rights abuses such as murder, enforced disappearance, arbitrary justice and intimidation, and entry bans against two of the most important Crimean Tatar politicians. The Society for Threatened Peoples reports that mosques, schools and apartments have been searched and that the Crimean Tatars' self-advocacy organization - the Mejlis - has been systematically rendered incapable of action. Teaching in the Crimean Tatar language has been severely restricted and businesses and properties are being "nationalized", which means expropriated with practically no compensation.

The Russian language is dominant in Crimea. The 2001 Ukrainian census found 10.1% Ukrainian-speaking, 11.4% Crimean Tatar-speaking and 77.0% Russian-speaking native speakers in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (excluding Sevastopol).

The Ukrainians have their main settlement in the north of the peninsula. There they represent the largest population group in several Rajonen. The Crimean Tatars mostly live in the center and east of the peninsula. Comparatively few Crimean Tatars live in the larger cities. The Russians mostly live in the cities, in the south and east of the peninsula. In the north, on the other hand, the Russian proportion of the population is sometimes well below the average.

The population of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (i.e. excluding Sevastopol) in 2001 and 1989 was composed of:

| ethnicities | Residents | 1989 (%) | 2001 (%) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russians | 1,180,400 | 65.6 | 58.5 | −11.6% |

| Ukrainians | 492.200 | 26.7 | 24.4 | −9.5% |

| Crimean Tatars | 243,400 | 1.9 | 12.1 | +540% |

| Belarusians | 29,200 | 2.1 | 1.5 | −31.1% |

| Tatars | 11,000 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + 16.2% |

| Armenians | 8,700 | 0.1 | 0.4 | + 270% |

| Jews | 4,500 | 0.7 | 0.2 | −69.8% |

| Poland | 3,800 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −29.1% |

| Moldovans | 3,700 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −31.2% |

| Azerbaijanis | 3,700 | 0.1 | 0.2 | + 70% |

| Uzbeks | 2,900 | 0.0 | 0.1 | +360% |

| Korean | 2,900 | 0.1 | 0.1 | + 22.6% |

| Greeks | 2,800 | 0.1 | 0.1 | + 12.0% |

| German | 2,500 | 0.1 | 0.1 | + 16.3% |

| Mordwinen | 2,200 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −49.8% |

| Tschuwaschen | 2,100 | 0.2 | 0.1 | −42.9% |

| Roma | 1,900 | 0.1 | 0.1 | + 13.1% |

| Bulgarians | 1,900 | 0.1 | 0.1 | + 3.7% |

| Georgians | 1,800 | 0.1 | 0.1 | + 21.9% |

| Mari | 1,100 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −37.8% |

| total | 2,024,000 | 100 | 100 | −0.6% |

The population in Sevastopol in 2001 was made up as follows:

| ethnicities | Residents | 1989 (%) | 2001 (%) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russians | 270,000 | 74.4 | 71.6 | −8.2% |

| Ukrainians | 84,400 | 20.7 | 22.4 | + 3.3% |

| Belarusians | 5,800 | 1.9 | 1.6 | −22.0% |

| Tatars | 2,500 | 0.3 | 0.7 | +140% |

| Crimean Tatars | 1,800 | 0.1 | 0.5 | + 490% |

| Armenians | 1,300 | 0.1 | 0.3 | + 220% |

| Jews | 1,000 | 0.7 | 0.3 | −64.8% |

| Moldovans | 800 | 0.3 | 0.2 | −30.0% |

| Azerbaijanis | 600 | 0.1 | 0.2 | +150% |

| total | 377.200 | 100 | 100 | −4.6% |

Historical overview of the population composition on the Crimean Peninsula:

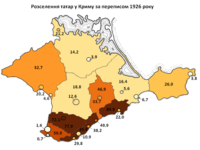

Distribution of the Crimean Tatars in Crimea in 1939

economy

The economy of the Crimea is mainly based on agriculture (fruits, vegetables, viticulture, poultry) and tourism. It is favored by the particularly mild climate on the peninsula. A well-known export product are Massandra Krimweine and Crimean sparkling wine , which is only partly produced in the Crimea. The former Ukrainian energy supplier Chernomornaftogaz, which is based in Crimea, has 66 billion cubic meters (largely offshore ) of natural gas reserves, which will fall when Crimea is connected to Russia and the company is nationalized. The sanctions imposed on the Russian Federation by the European Union, the USA and other states target the peninsula's energy and tourism sectors in particular.

irrigation

About 85% of the supply of the low-precipitation Crimea was via canals from the Ukraine from the Dnieper. The most important canal is the North Crimean Canal . After the split from Ukraine, there were disputes about the supply of water and its payment. Finally, in the spring of 2015, the state media of the Russian Federation reported that the water shortage had been remedied by a newly laid supply network.

Nuclear power plant (ruins)

In 1976, construction of the Crimean nuclear power plant began. Construction stopped in 1989. The construction made it into the Guinness Book of Records as the most expensive reactor construction in world history .

tourism

In the 19th century, the tsarist family and the Russian aristocracy built summer residences on the south coast of the Crimea, which began the role of the peninsula as a holiday and recreation region. Important artists, writers and the “rich and beautiful” spent the summer months on the Black Sea beach, some - like Anton Chekhov , who relied on the soothing climate for health reasons - settled down permanently.

During the Soviet period, the Crimea functioned as an all-union sanatorium with up to 10 million seasonal guests. The number of holidaymakers has fallen sharply since Ukraine gained independence, but tourism is still the most important economic factor on the peninsula. Recently, Western European tourists discovered the Crimea.

The port city of Sevastopol is located at the southern tip of the Crimea ; other well-known vacation spots are Yalta , Hursuf , Alushta , Bakhchysarai , Feodosia and Sudak . A tourist attraction is the longest trolleybus line in the world, operated by the Krymskyj trolejbus company, and runs between Yalta, Alushta and Simferopol. It leads, among other things, over the Crimean Mountains with views of the sea.

View of the Crimean Mountains near Alupka

View of the Orthodox Church in Foros

The Livadija Palace

Sports

In August 2015, the Crimean League was founded on the peninsula. It consists of eight football clubs.

The Crimea in literature

The ancient Greek name of the Crimea was " Tauris ". Accordingly, the drama Iphigenie auf Tauris by Euripides , which Johann Wolfgang Goethe adapted and Christoph Willibald Gluck and Joseph Haydn set to music, is located there.

The Crimea is the setting for numerous works of Russian literature, in which references to Ancient Greece are particularly emphasized. It began with Alexander Pushkin in his poem cycle Tauris ( Таврида ) and his poem The Fountain of Bakhchisarai ( Бахчисарайский фонтан ). The classical poets Afanassi Fet and Alexei K. Tolstoi also dedicated lyrical works to her.

The Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz wrote the Crimean sonnets after a trip to the peninsula , in which he also dealt with the culture of the Orient.

The young Lev Tolstoy , inspired by his experiences as an artillery officer during the Crimean War, wrote the Sevastopol tales, which made him known throughout the country for their pacifist statements. The city of Yalta is the setting for the famous story The Lady with the Dog by Anton Chekhov ; it provided the template for Nikita Michalkow's film Black Eyes , in which Marcello Mastroianni plays an aging bon vivant .

At the end of the 19th century, the Ukrainian poet Lesja Ukrainka came to the Crimea for a cure. She then wrote the collection of poems, Memories of the Crimea .

In Maxim Gorky's sketches from the Crimea to the everyday lives of their residents and summer visitors reflects. Some of the poets of the Silver Age of Russian literature at the beginning of the 20th century published cycles of poems with references to antiquity and high oriental culture, including Valery Brjussow , Ivan Bunin and Igor Severjanin . Next generation poets also contributed to the Crimean myth, including Anna Akhmatova , Marina Tsvetaeva , Ossip Mandelstam and the young Vladimir Nabokov , who later described the German occupation of Crimea in 1918 in his memoirs ("a silent army ... gray ghosts") . Ivan Schmeljow described the horrors of the Russian civil war on the peninsula in his novel The Sun of the Dead, which was praised by Thomas Mann .

During the Soviet era, Mikhail Bulgakov and Konstantin Paustovsky wrote stories whose plot is based on them. The regime critic Vasily Axionov was only able to publish his satirical novel The Island of Crimea , in which the peninsula is a sovereign state, in the West in 1979. He appeared in the USA.

In 1993 the tragic comedy Love in the Crimea by the Polish playwright Sławomir Mrożek premiered, which was also made into a film in 1998.

literature

prehistory

- Guido Bataille: The transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic on the Crimean peninsula and in the Kostenki-Borshchevo region on the Central Don. Adaptation strategies of late-middle Paleolithic and early-Upper Paleolithic groups , dissertation University of Cologne 2013. ( ub.uni-koeln.de ).

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

- Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick: A plaything of powers: The Crimea in the Black Sea region (VIth –XVth centuries). In: Stefan Albrecht, Falko Daim, Michael Herdick (eds.): The hill settlements in the Crimean mountains. Environment, cultural exchange and transformation on the northern edge of the Byzantine Empire. RGZM, Mainz 2013, ISBN 978-3-88467-220-4 , pp. 25-56.

- Stefan Albrecht, Michael Herdick, Rainer Schreg: New Research in the Crimea. History and society in the mountainous region of southwestern Crimea - a summary. In: Stefan Albrecht, Falko Daim, Michael Herdick (eds.): The hill settlements in the Crimean mountains. Environment, cultural exchange and transformation on the northern edge of the Byzantine Empire. RGZM, Mainz 2013, pp. 471-497, ISBN 978-3-88467-220-4 .

- Karl Georg Brandis : Cheronesos 19 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume III, 2, Stuttgart 1899, Col. 2254-2261.

- Lyudmila G. Khrushkova : Crimea. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 22. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-7772-0825-1 , Sp. 75-125.

Modern

- Kerstin S. Jobst: The pearl of the empire. The Russian Crimean Discourse in the Tsarist Empire. Constance 2007.

- Norbert Kunz: The Crimea under German rule 1941-1944. Germanization utopia and the reality of occupation. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-18813-6 .

- Christian Reder, Erich Klein (ed.): Gray Danube, Black Sea. Vienna Sulina Odessa Yalta Istanbul. Edition Transfer, Springer, Vienna / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-211-75482-5 (research, discussions, essays).

- Gwendolyn Sasse : The Crimea Question: Identity, Transition, and Conflict (= Harvard Series in Ukrainian Studies ). Cambridge 2014, ISBN 978-1-932650-12-9 .

Web links

- Crimean archipelago. A multimedia dossier from Dekoder.org . Dekoder-gGmbH

- The national question in the Crimea. Journey in the summer of 1996. ZIS study by Veit Kühne

- Historical footage of the Crimea, 1918 , filmportal.de

- Thomas Urban : Ukraine-Crimea Peninsula - Russia's embattled Riviera. In: sueddeutsche.de, March 8, 2014 (on the history of Crimea)

- Ulli Kulke : And suddenly Crimea belongs to Ukraine. In: The world . March 10, 2014

Individual evidence

- ↑ w1.c1.rada.gov.ua

- ↑ w1.c1.rada.gov.ua

- ↑ Population as of January 1, 2014. Average annual populations 2013. In: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved March 25, 2014 .

- ↑ Quotation from Wilhelm Tomaschek : Ethnological research on Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. Volume 1: The Goths in Tauria. Alfred Hölder, Vienna 1881, OCLC 162367099 , p. 43 ( Scan - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Berthold Seewald: Room for South Tyroleans - Hitler's storm on the Crimea. (No longer available online.) In: welt.de. Die Welt , July 2, 2012, archived from the original on April 10, 2014 ; accessed on October 1, 2018 .

- ^ Brian Glyn Williams: The Crimean Tatars. From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. Oxford / New York 2016: In 1944 around 20,000 Crimean Tatars - collaborators and their families fled with the Wehrmacht, 20,000 Crimean Tatar men fought as Soviet soldiers against the Wehrmacht, and 5,000 of 25,000 Soviet partisans in Crimea were of Crimean Tatar origin. Soviet records of the time also indicate that the vast majority of Crimean Tatars remained loyal to the Soviet Union.

- ^ Brian Glyn Williams: The Crimean Tatars. From Soviet Genocide to Putin's Conquest. Oxford / New York 2016.

- ^ Dante Corneli: Elenco delle vittime italiane dello stalinismo (dalla lettera A alla L). Tipografia Ferrante, Tivoli 1981.

- ↑ Putin now believes his own propaganda. In: The world. April 2, 2014.

- ↑ Azarov: The Truth About the Coup. Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-360-01301-9 .

-

↑ Crimean Transmission: Was the Dnieper Canal the Reason? Die Welt March 12, 2014, accessed December 8, 2018 Ivan Drábek: To return the Crimea? Hardly voluntarily. Pravda (Slovakia) . February 24, 2014, accessed February 26, 2014, in Slovak

- ^ Maria Drohobycky: Crimea: Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1995, ISBN 0-8191-9954-0 , p. 108.

- ^ Maria Drohobycky: Crimea: Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1995, ISBN 0-8191-9954-0 , pp. 40 and 41.

- ^ Political situation in the Crimea. Debate on Ukraine joining NATO. In: Ukraine Analysis. 12/06, p. 2 (PDF; 199 kB, accessed on March 6, 2014).

- ↑ Julian Mertens: Ukraine: Eggs and Fog Bombs in Parliament. Deutsche Welle , April 27, 2010, accessed March 6, 2014.

- ↑ FAZ : Moscow is sending more soldiers to the Crimea.

- ↑ Stephen Blank: Russia versus NATO in the CIS, published by Radio Free Europe on May 14, 2008, accessed June 23, 2015.

- ^ Hannes Adomeit : Russian military and security policy. In: Heiko Pleines, Hans-Henning Schröder (Eds.): Country Report Russia. Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb, Bonn 2010, ISBN 978-3-8389-0066-7 , p. 269.

- ↑ Simon Schuster: Putin's Man in Crimea Is Ukraine's Worst Nightmare. In: Time. March 10, 2014.

- ↑ Claus Kreß , Christian Tams : Against the normative power of the factual. The Crimean crisis from an international law perspective. In: International Politics . No. 3, May / June 2014, pp. 16-19.

- ^ Andreas Kappeler: Brief history of the Ukraine. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-67019-0 , p. 351.

- ↑ Urs Saxer: The Crimean conflict and international law. In: NZZ. March 18, 2014, accessed June 24, 2015 .

- ↑ International Law: Ukraine, Crimea, Russia - Annexation or Secession? Karl Albrecht Schachtschneider , December 17, 2014, accessed June 24, 2015 .

- ↑ Reinhard Merkel : The Crimea and international law: cool irony of history. In: FAZ. April 7, 2014, accessed October 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Crimean referendum: 96.77 percent vote for reunification with Russia - final result. In: RIA Novosti . March 17, 2014, accessed March 17, 2014 .

- ^ After the Crimean referendum. The fronts have remained. In: TAZ. March 17, 2014, accessed February 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Christian Weisflog: Crimean referendum heavily falsified. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . May 5, 2014, accessed May 5, 2014 .

- ↑ Chronicle of political and social events in Russia in 2014. (PDF; 666 kB) (No longer available online.) In: länder-analysen.de. The German Society for Eastern European Studies and the Research Center for Eastern Europe , pp. 25–29 , archived from the original on November 8, 2014 ; Retrieved November 8, 2014 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Chronicle: March 13-27, 2014. In: Federal Agency for Political Education. March 31, 2014, accessed November 8, 2014 (excerpt from previous source).

- ↑ Chronology of the Crimean Crisis. Disputed peninsula. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . April 7, 2014, p. 20 , accessed November 8, 2014 .

- ↑ Speech to Parliament. Putin seals annexation of Crimea. In: Spiegel Online . March 18, 2014, accessed November 8, 2014 .

- ↑ Will Englund: Kremlin says Crimea is now officially part of Russia after treaty signing, Putin speech. In: Washington Post . March 18, 2014, accessed November 8, 2014 .

- ↑ Putin okays draft treaty to make Crimea part of Russia. In: Jerusalem Post . March 18, 2014, accessed November 8, 2014 .

- ^ Announcement of the Kremlin of March 21, 2014: Laws on admitting Crimea and Sevastopol to the Russian Federation. In: kremlin.ru, accessed on March 22, 2014.

- ^ Announcement of the Kremlin of March 19, 2014: Agreement on the Accession of the Republic of Crimea to the Russian Federation submitted to State Duma for ratification. (No longer available online.) In: kremlin.ru. President of Russia, March 14, 2014, archived from the original on July 24, 2014 ; accessed on October 1, 2018 (English).

- ↑ UN News Center: Backing Ukraine's territorial integrity, UN Assembly declares Crimea referendum invalid. March 27, 2014.

- ↑ General Assembly of the United Nations : Territorial integrity of Ukraine. (PDF; 110 kB) Resolution. March 24, 2014, accessed October 30, 2014 .

- ↑ vek / dpa / Reuters: UN General Assembly condemns annexation of Crimea. In: Spiegel Online. March 27, 2014, accessed October 30, 2014 .

- ↑ Reuters.com, March 28, 2014 , accessed November 7, 2014.

- ↑ Complete Crimea without electricity. “Strommasten Gesprengt” orf.at, November 22, 2015, accessed November 22, 2015.

- ↑ No electricity in the Crimea. In: FAZ. November 22, 2015, accessed December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Putin activates electricity in Crimea, orf.at. December 2, 2015, accessed December 2, 2015.

- ↑ Dispute over power failure between Crimea and Kiev. In: orf.at. December 31, 2015, accessed December 31, 2015.

- ↑ (AFP): Russia: Putin inaugurates fourth and last part of the power line to the Crimea. In: Zeit Online. May 11, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2016 .

- ↑ The big money of the hero city. In: Novaya Gazeta. 15th August 2018.

- ↑ Otto Luchterhandt : Putin violates the Russian constitution. In: FAZ. April 18, 2014.

- ↑ Crimean activist fined for social media post from 2010. KyivPost, September 21, 2016.

- ↑ Putin: Russia does not want to war and does not want to annex Crimea. (No longer available online.) In: heute.de. March 4, 2014, formerly in the original ; Retrieved on October 1, 2018 (no mementos; the incomplete reconstruction of the website at mementoweb.org from March 4, 2014 does not show the population statistics). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- ↑ Crimea: One year on from annexation; critics harassed, attacked and silenced. In: www.amnesty.org. Retrieved April 11, 2016 .

- ↑ Ukraine: Fear, Repression in Crimea: Rapid Rights Deterioration in 2 Years of Russian Rule. In: hrw.org. Human Rights Watch , March 18, 2016, accessed April 11, 2016 .

- ↑ a b FUEN : Crimean Tatars suffer from human rights violations - the ban on assembly is supposed to silence the minority. For Human Rights Day on December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Linguistic composition of population Autonomous Republic of Crimea, according to All-Ukrainian population census data (2001). In: 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua .

- ↑ Служба статистики Республики Крым. (No longer available online.) In: sf.ukrstat.gov.ua. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014 ; Retrieved October 2, 2018 (Ukrainian).

- ↑ 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua

- ↑ 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua

- ↑ The Crimean government confiscates Ukrainian state-owned companies. In: The press . Vienna, accessed on November 9, 2014.

- ↑ Florian Willershausen: Crimean annexation [sic] will be expensive fun for Putin. In: Wirtschaftswoche. March 15, 2014, accessed October 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Ukraine allegedly turns off the waters of Crimea, which has been annexed by Russia. In: Augsburger-Allgemeine. May 1, 2014, accessed October 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Crimean farmers on dry land. In: NZZ. June 2, 2014, accessed October 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Russian military breaks Crimea water blockade. TASS April 20, 2015.

- ↑ Denis Trubetskoy: The newest league in the world. In: Die Zeit online. November 25, 2015.

- ^ Writer about the Crimea (Russian).

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Memory, speak. Reunion with an autobiography. German by Dieter E. Zimmer. Reinbek 1991, p. 332.

- ↑ filmpolski.pl .