Silk road

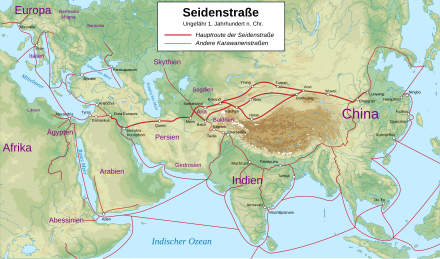

As the Silk Road ( Chinese 絲綢之路 / 丝绸之路, Pinyin Sīchóu zhī Lù - "the route / road of silk"; Mongolian ᠲᠣᠷᠭᠠᠨ ᠵᠠᠮ Tôrgan Jam ; short:絲路 / 丝路, Sīlù , Persian : جاده ابریشم) is the name given to an old network of caravan routes , the main route of which connected the Mediterranean area by land via Central Asia with East Asia . The name goes back to the 19th century German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen , who first used the term in 1877.

On the ancient Silk Road mainly silk was traded to the west , and wool, gold and silver to the east (see also India trade ). Not only merchants, scholars and armies used their network, but also ideas, religions and entire cultural groups diffused and migrated on the routes from east to west and vice versa. B. Nestorianism (from the late ancient Roman Empire) and Buddhism (from India ) to China. However, recent research has warned against overestimating the volume of trade (at least overland) and the transport infrastructure of the various trade routes.

A 6,400-kilometer route began in Xi'an and followed the course of the Great Wall of China to the northwest, passed the Taklamakan Desert, overcame the Pamir Mountains and led via Afghanistan into the Levant ; from there the goods were shipped across the Mediterranean . Only a few merchants traveled the entire route; the goods were transported in stages via intermediaries.

The trade and road network reached its greatest importance between 115 BC. BC and the 13th century AD. With the gradual loss of Roman territory in Asia and the rise of Arabia in the Levant, the Silk Road became increasingly unsafe and hardly traveled. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the route was revived under the Mongols ; among others it used Marco Polo at the time of the Venetians to travel to Cathay (China). It is widely believed that the route was one of the main routes that plague bacteria took from Asia to Europe in the mid-14th century, causing the Black Death there .

At the present time there are several projects under the name “New Silk Road” to expand the transport infrastructure in particular in the area of the historic Silk Road. The best known is probably the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

importance

Not only silk was transported on the Silk Road, but also goods such as spices, glass and porcelain ; with trade, religion and culture also spread. So Buddhism reached China and Japan via the Silk Road and became the dominant religion there. The Christianity penetrated through the Silk Road to China. The knowledge of paper and black powder came along the Silk Road to the Arab countries and from there later reached Europe.

Merchandise

For the West, silk was probably the most extraordinary commodity that passed the Silk Road. After all, this material gave the route its name. However, this term distorts the reality of trade, as many other goods were also exchanged via these trade routes. Caravans in the direction of China transported, among other things, gold, precious stones and, above all, glass, which is why researchers have pointed out that from an eastern perspective, the “Silk Road” could just as easily be called the “Glass Road”. In the other direction - besides silk - mainly furs , ceramics , porcelain, jade , bronze , lacquer and iron were worn. Many of these goods were exchanged en route, changed hands several times and thus gained in value before they reached their final destination.

In addition to silk, spices in particular were important trade goods from Southeast Asia until modern times . They were not only used as condiments and flavorings , but also as medicines, anesthetics , aphrodisiacs , perfumes and for “magic potions”.

Still, the most popular Chinese product was silk. The development of silk weaving in China can be traced back to the 2nd millennium BC. Chr. Lead back. The production of large quantities for export, along with the training of silk manufacturers, did not take place until the end of the " Warring States Period " in the 3rd century BC. The oldest finds of Chinese silk in Europe were made in the Celtic princely grave on the Heuneburg ( Sigmaringen district ), which dates from the 6th century BC. BC.

In the Roman Empire , like purple and glass, it was a luxury item . Only the richest could afford modest amounts of the precious material. In the time of the Pax Augusta , when the western end of the Silk Road was also safe, the Roman upper class increasingly demanded eastern silk, spices and jewels. Although it's Oströmern under Emperor I. Justinian in the outgoing Late Antiquity finally managed to build with the help of smuggled crawler own silk production, the import of Chinese silk was very significant.

Organization of trade

Bandits and robbers were very often a security problem because of the large flow of goods and riches. The Han Empire therefore equipped its caravans with special escorts and extended the Great Wall to the west.

Organizing transcontinental trade was complex and difficult. Countless animals, large numbers of drovers and tons of trade goods had to be organized and moved. People and animals had to be cared for on the long journey under difficult geographical and climatic conditions. Usually the merchants did not travel all the way to sell their wares. Rather, the trade took place over various route sections and several intermediaries. While the western end of the Silk Road was long controlled by the Parthians and later the Sassanids , in Central Asia it was mainly various groups of equestrian tribes (see, for example, Xiongnu , Iranian Huns , Kök Turks ) who dominated the exchange of goods.

Sogdian traders, whose contacts reached as far as China, played an important role . Letters received from Sogdian traders are also an important source of the history of the Silk Road.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish Radhanites also used the Silk Road. In addition to oases, the route was also interrupted by military stations such as stops for changing horses, which ensured through traffic.

The trample , which was native to Central Asia, was of great importance as a means of transport . It has the advantage that it is more heat-resistant than dromedaries and has a winter coat so that it is well adapted to the extreme temperature fluctuations typical of the continental climate in the steppe and mountain regions with large differences in altitude.

Recent research warns that the volume of land trade and the transport infrastructure of the various trade routes have often been overestimated because the Silk Road was not a single, continuous route from east to west. The transport was often connected with the handling of goods at different stations and was time-consuming. In the older research, the importance of transfer landscapes was not sufficiently appreciated, such as Central Asia and Persia.

Culture and technology transfer

The transfer of technical achievements, cultural goods or ideologies was less intentional than the exchange of goods. Long-distance travel of all kinds, whether for commercial, political or missionary reasons, stimulated cultural exchange between different societies. Songs, stories, religious ideas, philosophical views and unknown knowledge circulated among the travelers. For several centuries, the Silk Road formed the most enduring, far-reaching and diverse exchange between the Orient and the Occident .

In addition to the introduction of new foods, an agri-cultural exchange also took place.

Important techniques such as papermaking and letterpress printing , chemical processes such as distillation and the production of black powder, as well as more efficient harness and stirrups were spread westward from Asia via the Silk Road.

Spread of Religions

Religions were a particularly long-lived commodity that was transported on the Silk Road . For example, Buddhism came via the northern route from India to China and Japan. Some of the earliest descriptions of the Silk Road come from Chinese pilgrims who traveled to the Indian homeland of Buddhism.

Mongols and Turkic peoples originally worshiped the sky god Tengri , in Iran and Parthia Zoroastrianism prevailed , while in Sogdia a separate popular belief was widespread.

Christianity was present in Asia Minor and Iran early on. In the 5th century, the Eastern Syrian Church, which adhered to Nestorianism , was formed in the Sassanid Empire . At this time Nestorianism was able to spread into eastern Iran as far as Sogdia and Bactria . Samarkand was reached in the 8th century . In the Tarim Basin there was a first wave of missions in the 8th and a second in the 11th century. In the Siebenstromland in the 9.-14. Many Nestorian tombstones were erected in the 19th century. Believers had already reached the then capital of China, Xi'an , earlier , as documented by a stele erected in 781. A Chinese edict of 845 turned against all foreign religions and made Nestorianism disappear here by the 10th century. With the Mongol rule it experienced a second heyday and then finally disappeared in China in the 14th century. The faith also lasted among the Turkic peoples until the 14th century, when it was exterminated by Timur Lenk, a believer in Islam .

The Manichaeism originated from 240 n. Chr. In Mesopotamia and quickly spread to Persia, where he would not be against the Zoroastrianism prevailed, and in the east followed by Turan Depression . He was able to win over believers in Turfan , Merw and Parthia . In the important trading colonies of the Sogdians, there were Nestorians and Buddhists as well as numerous Manicheans, as was the case in 7th century China. In 762 the rulers of the Uyghur steppe empire professed Manichaeism and in the empire of Kocho this religion held a strong position alongside Buddhism. In Dunhuang the Manicheans disappeared in the 11th century, in Turfan only during the Mongol period in the 13th century.

At the turn of the century, Buddhism developed in the Indian-Iranian border region, in Gandhara and Kushana , under Hellenistic influence, the formal language with the human Buddha figure. Kanishka I., King of the Kushana Empire, was for political reasons a promoter of Buddhism in the area of the Middle Silk Road; the religion gained many followers in Sogdia in the 3rd and 4th centuries. After China Buddhism arrived for the first time to the era, strengthened during the Northern Wei Dynasty in the 4th and 5th centuries, but a broad impact he displayed until the 7th century. After the Mongols under Kublai Khan came into increased cultural contact with China in the 13th century, Buddhism was also able to gain followers. In East and West Turkestan, Buddhism disappeared with the advance of Islam, in the Tarim Basin only in the 15th century. It was safe in Dunhuang and China.

These three religions coexisted more or less peacefully for a long time in many places along the Silk Road. After the death of Mohammed in 632 AD, Islam spread ( Islamic expansion ) and soon the western part of the Silk Road and with it the trans-Asian trade was under Islamic control. After the conquest of the New Persian Sassanid Empire in 642 AD, expansion continued in an easterly direction. Islam first spread in the urban centers along the Silk Road, and later in the rural areas. Islamic communities also emerged in Central Asia and China. Under Timur Lenk, Islam was again violently spread in the 14th century.

Spread of disease

Just like religious ideas or cultural goods, diseases and infections repeatedly spread along the Silk Road. Long-distance travelers helped the pathogens to spread beyond their area of origin, attacking populations that had neither inherited nor acquired immunity to the diseases they caused. This resulted in epidemics that could have dramatic consequences.

Probably the best known and most momentous example in Europe of the spread of diseases along the Silk Road is the spread of the plague in the 14th century. According to a hypothesis by the author William Bernstein , the Pax Mongolica that followed the Mongol storm in the 13th century allowed again intensified and direct trade contacts between Europe and Asia. This lively exchange also brought plague bacteria, which are mainly found in wild rodent populations in Asia, to Europe. The plague also reached Central Europe around 1348 via merchant ships from Kaffa on the Crimean peninsula . The transport of furs in particular favored their rapid spread. It is unclear in this context why the Black Death in China and India did not cause a comparable number of deaths. In the similarly densely populated India of the 14th century there was even an increase in population; In much more densely populated China, more people died of famine and the wars against the Mongols than of the Black Death. There are also no historical records of a pandemic comparable to the Black Death in Europe.

course

To nature

The Silk Road was anything but a route given by nature. Running through arid regions and deserts from the Mediterranean Sea to China, it is one of the most inhospitable stretches on earth, running through scorched, waterless land and connecting one oasis to the next. The Mesopotamia , the Iranian Highlands and the Turan Lowlands are on the way. If you have the Tarim Basin with the Taklamakan reached -Wüste, one is surrounded by the highest mountain ranges of the world: in the north of the towers Tian Shan on the west of the Pamir , in the southwest of the Karakoram and the south of the Kunlun . Only a few icy passes, which with their deep gorges and 5000 meters of altitude to overcome, are among the most difficult in the world, lead through the mountains. The climate is also harsh: sandstorms are frequent, in summer the temperature rises to over 40 ° C and in winter it often falls below −20 ° C.

Due to the geographical nature of the area, only a few fixed traffic and trade routes developed. In many places there were alternatives and alternative routes.

Main route

Most of the time, the name “Silk Road” refers to the route described here, which has a few branches and which, due to its length, is divided into a western, central and eastern part.

The core of the Silk Road, sometimes also called the Middle Silk Road , stretches from the eastern Iranian plateau and the city of Merw in the west to the Gobi desert and the city of Dunhuang in the east as well as the junction to the south to Kashmir and Peshawar . It connects three of the most important Asian cultural areas: Iran , India and China. The country is characterized by deserts with old oasis cities, the Kazakh steppe in the west and the Mongolian steppe in the east as well as high mountains.

The main route is divided into different branches. From Merw one could cross the Oxus (today Amudarja ) and reach the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand in Transoxania .

From there, a north-east branch led via Tashkent north of the Tian Shan Mountains via Beshbaliq (near Ürümqi ) and via Turpan (Turfan), Hami ( Kumul ), reunited with the main branch near Anxi (today Guazhou ).

The main branch followed from Samarkand from the upper reaches of the Jaxartes ( Syr-Darja ) through the Ferghana Valley, which was irrigated by this, via Kokand ( Qo'qon ) and Andijon , crossed the Tian Shan Mountains and reached Kashgar ( Kaxgar ) in the Tarim Basin .

The Taklamakan desert in the Tarim Basin could be avoided in the north or in the south. Along the southern edge it went through Yarkant , Khotan (Hotan), Yutian , Qarqan , Keriya , Niya , Miran and Qakilik , until one finally reached Dunhuang . From the 2nd century onwards, when a change in climate brought more water to the region, this was the usual route.

Later the oases on the southern edge dried up again, and from the 5th century the route along the northern edge became common: from Kashgar (Kaxgar) it went via Tumshuq (Tumxuk), Aksu , Kuqa (Kucha), Karashar, Korla , Loulan and finally one also reached Dunhuang.

From Kuqa (Kucha) there was another branch north-east to Turpan (Turfan) and then on like the north-east branch described above. The Siebenstromland was also connected by paths.

To get to India, very high mountains had to be crossed. From Merw one came along the upper reaches of the Oxus (Amu Darja) via Baktra (today Balkh ) to the Khyber Pass , crossed the Hindukush and reached the northwest Indian province of Gandhara to Begam , Kapisa and Peshawar .

From the 3rd century, a different route was used: from the upper Indus about Gilgit and Hunza -Tal was Karakorum crossed -Gebirge and Kashi (Kashgar), the Tarim Basin reached. This route corresponds to the course of the Karakoram Highway built from the 1960s .

The Eastern Silk Road joins the Middle Silk Road to the east and leads to the important cities of China. It led from Dunhuang east via Anxi (today Guazhou ) through the Gansu or Hexi corridor via Jiayuguan (up to this point the Great Wall was built to protect the trade route), Zhangye and Wuwei to Lanzhou , then via Tianshui and Baoji to Chang ' on . From there it went northeast to Beijing or east to Nanjing .

The Western Silk Road connects to the west of the Middle Silk Road and leads to the port cities on the Mediterranean. It led from Merw via Maschhad , Damghan , Tehran , Ekbatana (today Hamadan) and Baghdad to Palmyra . From there it went to the northwest via Aleppo to Antioch (today Antakya) and Tire to Constantinople (today Istanbul) or to the southwest via Damascus and Gaza to Cairo and Alexandria .

Other routes

- From the upper Indus valley to the port of Debal in today's Pakistan at the mouth of the Indus. From there by ship to Mesopotamia or around the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt.

- A variant of the previous route, but this time via the port of Barygaza ( Bharuch ), further east on the Gulf of Khambhat .

- From Samarkand on Jaxartes ( Syr-Darja ) through the Kazak steppes and the Caspian Depression to the Crimea and the Black Sea .

- Extension from the Chinese cities to Korea and Japan.

- From the Chinese port cities by ship along the coast through the Strait of Malacca to the ports on the Indian east coast, around the Indian peninsula to the ports on the Indian west coast. From there to the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia or the Red Sea and Egypt or Palestine.

- From the southwest Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan via Burma to Bengal to the trading cities in the Ganges and Brahmaputra delta .

- From China via Tibet to Bengal.

- On connected with the Silk Road paths through the eastern Pamir was in the 1930s Pamirstraße built.

story

The oldest reports on the course of the Silk Road come from Greco-Roman antiquity. Herodotus wrote about 430 BC. The stations of the route are designated with the names of the peoples living there. According to his description, the road ran from the mouth of the Don first to the north, before it turned east to the area of the Parthians and then on a caravan path north of the Tian Shan to the western Chinese province of Gansu .

Connections between inner-Asian areas as well as between China and Europe have existed since ancient times, at least since the beginning of the Bronze Age . Among other things, they were based on the exchange of knowledge of metal extraction and processing as well as the exchange of trade goods, enabled diplomatic contacts and also promoted knowledge of the other culture. These connections were by no means continuous, mostly through intermediaries and were repeatedly interrupted for long periods of time in which trade , traffic and the exchange of information were hindered.

Early days

In the 5th century BC The Persian King's Road, measuring 2699 km, was laid out by the Persian King Dareios I. In the eastern part it formed the course of the later Silk Road.

That of Alexander the Great until 323 BC The great empire that was established in BC also united the area between the Mediterranean Sea and Bactria under one rule and reached as far as the Fergana Valley and the Indian Taxila . The development of a continuous trade connection between East and West was made possible by the Achaemenid Empire and the subsequent Hellenistic empires.

The Seleucid Empire and the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (both 3rd to 2nd centuries BC) and the Hellenism in Central Asia in general were beneficial for the development of the Western Silk Road.

A crucial political prerequisite for the full opening of the eastern end of the Silk Road was the Chinese expansion to the west. Under the emperor Wudi (141–87 BC) the size of the Han empire almost doubled . He responded to border threats by conquering enemy territory. His armies advanced far north, south and west and subjugated numerous adjoining states. 121 and 119 BC The Chinese cavalry defeated the Xiongnu and drove them northwards. As a result, China controlled the Gansu Corridor and Central Asia. Wudi's troops took possession of the Pamir and Ferghana , and so the trade routes between China and the west could be opened.

wedding

In the years that followed, trade flourished along the Silk Road, flooding the capital of the Han Empire with Western travelers and luxury goods.

The Parthians stood from 141 BC. At the height of their power. Under the successful Parthian king Mithridates II (124 / 123–88 / 87 BC) was 115 BC. The Silk Road "opened": A delegation of the Chinese Emperor Han Wudi paid their respects.

While the eastern part was relatively safe, from 55 B.C. Conflicts between the Romans and the Parthians, which only began with the first Roman emperor Augustus in 20 BC. Were ended. As a result, trade with the Far East ( Roman-Chinese relations ) revived .

In late antiquity , the open trade between East Current / Byzantium and the New Persian Sassanid Empire was severely hampered by the Roman-Persian wars in the 3rd to 7th centuries, but was never completely interrupted. Part of the east-west trade during this period may have been directed alternatively via the Arabian Peninsula. In addition, the maritime India trade ( Roman-Indian relations across the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean) played an important role in the Roman Empire up to the end of late antiquity .

The following Central Asian peoples (who often built steppe empires ) were also involved in the development of the Silk Road :

- The Saks , which in the 1st century BC Appeared in northern India and formed an empire in the Tarim Basin until the 10th century .

- The nomadic, Altai-speaking Xiongnu established in Gansu and Mongolia in the 3rd century BC. An empire that was founded in 48 BC. Split. Some tribes later settled the Ordos Plateau , their rule in Mongolia ended in 155 AD.

- The Yuezhi , sometimes referred to as the Tocharers , created an empire that lasted until the late 7th century AD.

The late ancient Central Asia was a politically fragmented space:

- In the 5th century the so-called Iranian Huns appeared , which were very probably not directly related to the Huns in Europe. Century own rulers in Bactria. These include the Kidarites , the Alchon group, the Nezak group and finally the Hephthalites . The Chionites , who are probably related to the Kidarites , appeared before that in the 4th century .

- The nomadic Rouran established an empire in AD 400 that stretched from the Tarim Basin to the far east and lasted until AD 552.

- The Sogdians did not form a state, but for a long time shaped the cultural life in the oasis cities and played an important role in the economic life of the Silk Road. The Sogdian city-states then went under , like other rulers along the old trade routes, in connection with the Islamic expansion in the 8th century (see Dēwāštič and Ghurak ).

- The empire of the Gök Turks , founded in 552, encompassed large parts of Central Asia and Mongolia, with Sogdians playing an important role in trade and administration (see Maniakh ). It threatened Persia in the west and China in the east. However, the two Turkish khanates themselves were threatened by external (Chinese and later Arabs) and internal conflicts (revolts such as those of the Türgesch , which became the inheritance of the western khanate around 700) and finally went under in the middle of the 8th century.

- The originally nomadic Tabgatsch settled down, founded the Northern Wei Dynasty and in the 5th and 6th centuries ruled the area between Northern China, the Tarim Basin and the Mongolian steppe.

- The Buddhist Tibetans , who founded their own empire in the 7th century, occupied Gansu in the 8th century.

The Silk Road experienced another heyday in the late 7th century during the Chinese Tang Dynasty , which replaced the Persians as the dominant power over the Silk Road. The second Tang Emperor Taizong brought large parts of Central Asia and the Tarim Basin under his control. However, the Arabs conquered Central Asia with heavy losses in the 8th century and also stopped Chinese expansion ( Battle of Talas 751).

After the loss of territory through the Arab conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries, the Byzantine Empire was able to settle in the 10th / 11th. In the 19th century, temporarily securing access to the Silk Road again and remained a main transshipment point for Eastern goods. The trade by sea was also important.

After the Tang period, during the Five Dynasties from 907 AD, trade routes became increasingly unsafe and trade along the Silk Road decreased. The Buddhist Tanguts (or Xixia), descendants of the Tabgatsch, who are related to the Tibetans , expanded their empire to Gansu in the 10th century . In 1227 this empire was destroyed by the Mongols.

The expansion of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century ushered in an era of frequent and extensive contacts. As soon as they had established order and stability in their new possessions, the Mongols began exchanges with strangers. In their universal claim to power, they were hospitable to foreign travelers, even if their rulers had not submitted. During this period, also known as Pax Mongolica , there was a sharp increase in the exchange of goods and people, without, however, reaching the size of the Tang Dynasty.

The vast Mongol Empire began to decline as early as 1262. Only the first three generations after Genghis Khan were able to hold the empire together and expand it further. According to Möngke Khan , a single state was replaced by a community of Chagatai Khanate (until 1565), Ilchanat (until 1507), Golden Horde (until 1502) and the Yuan Dynasty (until 1387). This later Mongolian Empire also had a Great Khan , but this was not always fully recognized by all Mongolian Khanates . The last great khan who actually ruled all Mongolian kingdoms was Timur Khan (until 1307). After that, the other khans repeatedly paid tribute to the respective great khan, especially Toqa Timur , as well as similar gestures of submission and solidarity, but the political fortunes of the Mongol Empire were largely decentralized. In this respect, from 1307 the Mongolian Empire was more of a confederation of states under more formal than actual unitary leadership. Despite inadequate political unity, cohesion was still clearly visible after 1307. It manifested itself, among other things, in the law codified in the Jassa , the postal and communication system (Örtöö and Païza) and the common art and cultural assets such as writing and language in particular .

In 1273/74 Marco Polo used the Silk Road for his trip to China. In addition to his travel reports, there are other similar reports, such as the "Ystoria Mongalorum" by Johannes de Plano Carpini and that of Wilhelm von Rubruk .

Decline

The decline of the Silk Road began with the Song Dynasty and was favored by the increased Chinese sea trade, the emergence of new markets in Southeast Asia and the high tariff demands of the Arabs . Another important reason was the drying up of the glacier-fed rivers around the Taklamakan and Lop deserts in the central part of the Silk Road.

On the sea route, the dangers of the long journey and the duties to the intermediaries were eliminated. The Silk Road finally lost its importance in the course of the global expansion of the European sea powers in the early modern period . Trade across the Silk Road was replaced by ships, with Chinese traders taking their junks as far as India and Arabia . Europeans have been severely restricted in their trade with China since the Song era. During the sea expeditions, one of their main goals was to find the legendary Cathay (China) by sea. It was not until 1514 that the Portuguese reached China and quickly established a lively trade, later occupied by Spain. Since the mid- 16th century , the Middle Kingdom has been the main beneficiary of the European colonies in the New World. A large part of the precious metal extracted there was brought to China to buy goods for Europe. Over time, ships of the trading companies replaced the Silk Road as a connection to East Asia in order to procure luxury articles and art objects for the European nobility.

The cities along the Silk Road fell into disrepair, formerly flourishing cultures disappeared in a long process and were forgotten for centuries.

exploration

The first explorations by Europeans in Chinese Central Asia were undertaken by so-called "Moonshees", locals recruited by the English to survey the unknown land. On June 12, 1863, the Indian Mohammed-i Hammeed set out and traveled from Kashmir to Yarkand.

From 1878 research trips into the core area of the Silk Road began, among others by Sven Hedin (1895), Aurel Stein , Albert Grünwedel , Albert von Le Coq , Paul Pelliot , Pjotr Kusmitsch Koslow and Langdon Warner . Further trips were financed by the Japanese Ōtani Kōzui . In the following years many ruins were rediscovered and mapped, and manuscripts and frescoes were brought to German, Russian, French, Japanese and English museums. Sven Hedin undertook another scientific expedition along the Silk Road from 1927 to 1933; 1933–1935 another expedition followed on behalf of the Chinese government. After the end of the Second World War , China carried out the exploration of the part of the Silk Road lying on its territory itself, an important archaeologist was Huang Wenbi .

Today, China laments the theft of many cultural assets by the western expeditions of that time.

Silk road today

Expansion of the traffic routes

The long-neglected transport routes have received more attention since the 1950s and especially since the end of the Soviet Union. Following on from the old name "Silk Road", many new projects are referred to as the "New Silk Road".

The United Nations has been supporting the expansion of the Asian transport network ( Asian trunk road project ) since the 1950s . Since the 1990s, the “ Europe-Caucasus-Asia transport corridor ” (TRACECA) initiated by the EU has been promoting the expansion of the infrastructure between Europe and Central Asia. In 2000 the Russian government started the “International North – South Transport Corridor” (INSTC) in response to TRACECA.

The infrastructure project “ Belt and Road Initiative ” (BRI), which China has been pursuing since 2013, has received the most public attention . To this end, a wide variety of facilities (e.g. deep-sea or container terminals ) and connections (such as rail lines or gas pipelines ) are being developed or expanded.

Belt and Road Initiative

The aim of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is to create a Eurasian economic area that extends from the Yellow Sea on the east coast of China to the Atlantic Ocean and also includes Africa. Existing corridors are on the one hand land connections via Turkey or Russia and on the other hand connections from the port of Shanghai , via Hong Kong and Singapore to India and East Africa , Dubai , the Suez Canal , the Greek port of Piraeus to the logistics hub around Trieste.

The economic traffic with Africa is to run largely on the "Maritime Silk Road" ("Maritim Silk Road" or "21st Century Maritim Silk Road") in the south of Asia. It connects the Chinese coast and all of Southeast Asia with the Middle East and East Africa all the way to Europe.

Since 2005, billions of dollars have been invested in the renovation and expansion of the route network; The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) started in 2013 - it encompasses around 70 countries and an investment framework of up to $ 1,000 billion. Ports, roads, railways, logistics centers and trading centers will be built or expanded along the “new Silk Road” in order to create new trade corridors between Asia, Africa and Europe. The initiative is not a sentimental simulation game with old trade routes between the lagoon city of Venice and the distant Orient, but serves strategic considerations for geopolitical economic competition. The planned economic corridors and transport lines extend by sea from the Shanghai deep-water port of Yangshan , via Hong Kong , Singapore , Port Klang (Malaysia), Laem Chabang (Thailand) and Colombo to Djibouti and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and via the Suez Canal , the Greek port of Piraeus (which runs through Chinese Investors to a hub in the eastern Mediterranean) to the deep water and free port of Trieste with its links to Central Europe. As a land route, they reach from the Chinese coastal city of Yiwu via Kyrgyzstan, Iran to Turkey or via Beijing and Moscow to Western Europe. Because of the countries involved, such as Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia or Uzbekistan, overland routes in particular are not necessarily considered to be sustainable, safe, passable and permeable. There are also considerable efforts in the Arab region (particularly in Saudi Arabia and Egypt) and in Iran to become part of the maritime transfer between China and Europe by expanding the infrastructure. For many of these projects, the model is the Jebel Ali Free Zone in Dubai, where 7,000 companies are already based. According to estimates, trade along the Silk Road could soon account for almost 40% of total world trade, with a large part coming from the sea.

Long-distance trade routes that are already important today run via Trieste to Turkey or Greece and from there via Iran or the Suez Canal to China. Especially with regard to the land connections to East Asia, trailers are used in RoRo traffic. Since 1990 there has been a 10,870-kilometer rail link connecting Rotterdam in Europe with the east Chinese port city of Lianyungang in Jiangsu Province .

Land routes

Part of the Silk Road between Pakistan and the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in China consisted of a gravel road when work began on upgrading it to an asphalt multi-lane highway ( Karakoram Highway ) in 1958 . The United Nations started the project for a trans-Asian trunk road in 1959 . The UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) has been promoting a continuous rail link between Singapore and Istanbul since the 1950s , the Trans-Asian Railway . 4 corridors have been planned since 2001.

The construction of roads, facilitated by the discovery of large oil reserves, has facilitated access to the inhospitable areas and the regions have been industrialized. The trade routes themselves have also been reopened and are not least important for tourism. The Asian highway network has recently been expanded by 32 Asian countries and the United Nations ( Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific ).

A commercial freight train connection between China and Germany has been sought under the name Trans-Eurasia-Express since 2008, and the Yuxinou has been a regular freight train between Chongqing and Duisburg since 2012 . Since 2011, Hewlett-Packard has had laptops and accessories transported from the production site in Chongqing to Duisburg in three weeks during the summer months. Customs clearance was simplified by the Belarus-Kazakhstan-Russia customs union, which came into force in 2012 . A total of around 1,700 freight trains ran between China and Europe in 2016; in May 2017 116 trains ran from Duisburg to China.

Sea routes

Under the name of “Maritime Silk Road”, the BRI is also promoting the expansion of maritime trade between China, the other Asian countries, Africa and Europe - parallel to the land routes. There are also fundamental changes in the flow of goods and trade:

- The Pacific is developing into the hub of world trade

- The Atlantic ports are relatively less important

- Asian-European transport routes are shifting from northwestern Europe to southern Europe

The important ports of Trieste and Piraeus in particular benefit from the upswing in southern Europe , but also the northern Adriatic ports of Venice, whose port, with a draft of 12 meters, is not a deep-water port, and Koper, which, however, does not have a high-performance railway line for inland connections. Fast connections by truck and train and the use of the Suez Canal play a role, especially for goods such as clothing, electronics and car parts. In addition to networking with Japan, China, South Korea and Southeast Asia, this also applies to trade with India and Pakistan and especially with Mumbai and Calcutta .

Within Europe, the “Maritime Silk Road” promotes networking between the regions with regard to railway junctions and deep-water ports. For example, the Belgrade-Budapest railway line is being expanded. The port of Duisburg is also traditionally connected to the North Sea ports such as Rotterdam and Antwerp, but now cooperates with the port of Trieste, which, with its draft of 18 meters and its connection across the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal to the Far East, is the end point of the "maritime silk road" applies. The existing freight train connections between the seaport and the logistics location Kiel (connections to Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Lithuania and Russia) with Trieste (the most important EU port for ferry lines with destination Turkey) and thus the connections to Scandinavia and the Orient get extended. With its connections, Deutsche Bahn is developing the northern Italian port of Monfalcone into an automobile hub on the Adriatic coast in order to shorten transport times by up to eight days. There are also freight train connections on the Adriatic-Baltic axis between the Trieste junction and the important Baltic Sea port of Rostock, which also includes the Scandinavian countries. Since 2015 to 2018, the departing freight trains in the port of Trieste have almost doubled to 10,000, with the rail connections to Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, Belgium, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic being particularly frequented.

tourism

Today the Silk Road has a rather mysterious, adventurous status. The oriental mysticism of the route is brought closer to the West through books and journeys “in Marco Polo's footsteps” attract a growing number of tourists to these remote regions.

China recognized the tourist potential very quickly by opening its doors to foreign travelers in the late 1970s. As a result, many sights and cultural monuments along the Silk Road have been restored and official care is taken to ensure that these monuments are preserved. In addition, archaeological excavations have been used to trace life along the Silk Road. Travelers along the Taklamakan Desert come across city ruins and remains of caves. A main attraction, however, is the population and the lifestyle that has been preserved to this day. Many tourists today come from Japan to visit the sites that the Buddhist religion passed on its way to Japan .

A trip to the Taklamakan area is still very difficult even today, despite some relief due to the climatic and geographical conditions.

The last gap in the railway connection along the Silk Road was closed in 1992 when the international Almaty - Ürümqi line was opened. Nevertheless, there are no through trains or timed transfer connections Beijing - Tehran or Beijing - Moscow along the Silk Road .

World Heritage

Several countries have put sites along the various branches of the Silk Road on their list of proposals for inclusion in UNESCO World Heritage. The World Heritage Committee then suggested submitting the proposals grouped according to individual routes. A joint proposal by the People's Republic of China , Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan for a serial transnational World Heritage Site along the corridor from the Seven Rivers in Central Asia via the Tian Shan Mountains to Central China was launched in 2014 under the title “ Silk Roads: the road network of the Chang'an Tianshan Corridor "Added to the World Heritage List .

smuggling

The former Silk Road is now also known as the Heroin Highway because it is used e.g. B. the smuggling of drugs, mainly opium and heroin , from Afghanistan to Europe, China and Russia and the transport of the acetic anhydride necessary for the production of heroin from Europe back to Afghanistan. For example, around 700 tons of heroin are smuggled through Tajikistan every year, only around 43 tons of different drugs are confiscated.

Here are z. For example, there is no differentiation between the container trucks of the NATO protection forces of Afghanistan (for supplies from Central Asia) and the smugglers, because the NATO trucks are inconspicuously camouflaged to protect the military goods they may contain.

In Kyrgyzstan , part of the Silk Road is mined due to border disputes (2011).

Geostrategic Aspects

With the end of the Soviet Union and the strengthening of China, the core areas of the Silk Road, which had long been on the edge, are again attracting more public attention. These core areas include

- the westernmost province of China, Xinjiang

- Afghanistan

- with Kashmir the north of India as well as the northern parts of Pakistan

- Tajikistan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Uzbekistan

- Turkmenistan

- the (former) Khorasan Province in northeastern Iran .

There is an accumulation of unsolved, often bloody conflicts in the region. There is an overlap between ethnic conflicts and Islamist tendencies, as well as the attempts by Russia to restore lost influence and the attempts by China and the USA to gain influence and the efforts of all three great powers to oppose Islamism.

In 1999, US interests in Central Asia were defined in the US with the “ Silk Road Strategy ”. The economic goals of Europe were defined in 1993 in the TRACECA project , the Chinese goals from 2013 onwards in the “ One Belt, One Road ” project (OBOR, “One Belt, One Road”).

Other uses of the name

- The so-called Silk Road rally runs at most in the broadest sense on routes of the historic Silk Road.

- The film The Children of the Silk Road tells a story in Nanjing (China) during the Second World War.

- On May 21, 2016, an asteroid was named after the Silk Road: (229864) Sichouzhilu .

The English name Silk Road or Silk Way:

- The Korean online role-playing game Silkroad Online was launched in 2005, followed by Silkroad-R in 2011 .

- The Azerbaijani airlines Silk Way Airlines and Silk Way West Airlines use the name because a route on the Silk Road ran through Azerbaijan.

- The e-commerce platform Silk Road , notorious illegal goods because of trade.

Use as street name:

literature

- Bruno Baumann : The Silk Road Adventure. In the footsteps of old caravan routes , National Geographic paperback, 2nd edition. August 2005, ISBN 3-89405-254-6 .

- Craig Benjamin: Empires of Ancient Eurasia. The First Silk Roads Era, 100 BCE-250 CE. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2018.

- Luce Boulnois: la route de la soie Éditions Olizane, 3 e édition, Genève 1992, ISBN 2-88086-117-9 .

- Edouard Chavannes : Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux. Librairie d'Amérique et d'Orient, Paris 1900 (Reprint: Cheng Wen Publishing Co., Taipei 1969).

- Jean-Pierre Drège: Marco Polo and the Silk Road. Maier, Ravensburg 1992 (Adventure Story 30), ISBN 3-473-51030-0 .

- Richard Foltz: Religions of the Silk Road. Premodern Patterns of Globalization. 2nd edition, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1 .

- Irene M. Franck, David M. Brownstone: The silk road. A history. New York et al. a. 1986, ISBN 0-8160-1122-2 .

- Peter Frankopan : Light from the East. Rowohlt, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-87134-833-4 .

- Peter Frankopan: The New Silk Roads. The Present and Future of the World. Bloomsbury Publishing, London a. a. 2018.

- Valerie Hansen: The Silk Road. A history with documents. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2016, ISBN 978-0-19-020892-9 .

- Sven Hedin : The Wandering Lake. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1994, ISBN 3-7653-0180-9 .

- Hans Wilhelm Haussig : The history of Central Asia and the silk road in pre-Islamic times. 2nd edition WBG, Darmstadt 1992.

- Hans Wilhelm Haussig: The history of Central Asia and the silk road in Islamic times. WBG, Darmstadt 1988.

- Uta Heinzmann, Manuela Loeschmann, Uli Steinhauer and Andreas Gruschke : sand and silk. Fascination of the Chinese Silk Road. Freiburg i. Br. 1990, ISBN 3-89155-095-2 .

- Thomas O. Höllmann: The Silk Road. Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-50854-5 ( review )

- Peter Hopkirk : Bouddhas et rôdeurs on the route de la soie. Philippe Picquier, Arles 1995, ISBN 2-87730-215-6 .

- Peter Hopkirk: The Silk Road: In Search of Lost Treasures in Chinese Central Asia. Translated from English by Hans Jürgen Baron von Köskull. rororo non-fiction book, Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1990, ISBN 3-499-18564-4 .

- Ulrich Huebner u. a. (Ed.): The Silk Road. Trade and cultural exchange in a Eurasian network of routes. EB-Verlag, 2nd edition. Hamburg 2005 (Asia and Africa 3), ISBN 3-930826-63-1 .

- Edith Huyghe, François-Bernard Huyghe: La route de la soie ou les empires du mirage. Petite bibliothèque Payot, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-228-90073-7 .

- Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. Cultural bridge between east and west. Cologne 1988 (DuMont documents), ISBN 3-7701-1790-5 ; The Silk Road - trade route and cultural bridge between east and west. 2nd Edition. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990.

- Folker E. Reichert: Encounters with China. The discovery of East Asia in the Middle Ages. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1992, ISBN 3-7995-5715-6 .

- Wilfried Seipel (Ed.): Incense and silk. Ancient cultures on the Silk Road. Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-900325-53-7 .

- State Museum for Ethnology Munich (Ed.): Art of Buddhism along the Silk Road. Munich 1992.

- Helmut Uhlig: The Silk Road. Ancient world culture between China and Rome. Bergisch Gladbach 1986, ISBN 3-7857-0446-1 .

- Susan Whitfield: Life Along The Silk Road. University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles 1999.

- Frances Wood : Along the Silk Road. Myth and History. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007.

- Alfried Wieczorek, Christoph Lind (Ed.): Origins of the Silk Road. Sensational new finds from Xinjiang, China. Exhibition catalog of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums, Mannheim. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2160-2 .

Web links

- depts.washington.edu: Silk Road Project (with translated sources and further information)

- Deutschlandfunk.de cultural issues January 12, 2020, Mayke Wagner in conversation with Karin Fischer: Give and take - cultural exchange on the Silk Road

- FAZ.net : China's Long Way West

- silk-road.com

- Nikolaus Egel, tabularasamagazin.de: A Brief History of the Silk Road , China's New Silk Road. A myth and its legacy

- zum.de: Origins of the Silk Road: Sensational new finds from Xinjiang, China (Exhibition 2008 in the Museum of World Cultures D5 in Mannheim )

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e Silk Road. In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved August 10, 2017 .

- ↑ Khodadad Rezakhani: The Road That Never Was. The Silk Road and Trans-Eurasian Exchange. In: Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 30, 2010, pp. 420–433.

- ^ U. Knefelkamp: The trade routes of precious textiles to Central Europe from the 10th to the 15th century. In: Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments: Textile grave finds from the Sepultur of the Bamberg Cathedral Chapter. International Colloquium, Seehof Castle, 22./23. April 1985. Arbeitshefte 33. München 1987, pp. 99-106; HJ Hundt: About prehistoric silk finds. In: Jahrb. Des Röm.-Germanisches Zentralmuseums Mainz 16, 1969, pp. 59–71.

- ↑ Étienne de La Vaissière : Sogdian Traders. A history. Leiden 2005.

- ^ Valerie Hansen: The Silk Road. A history with documents. Oxford 2016, p. 193 ff.

- ↑ Khodadad Rezakhani: The Road That Never Was. The Silk Road and Trans-Eurasian Exchange. In: Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 30, 2010, pp. 420–433.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 83.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 87.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 91.

- ^ William Bernstein: A Splendid Exchange - How Trade Shaped the World. Atlantic Books, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-84354-803-4 , pp. 138 f.

- ↑ George D. Sussman: What the black death in India and China? Bulletin of the history of medicine, 2011, 85 (3), 319-55 PMID 22080795 .

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 8.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 8 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 12.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 12.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 48.

- ↑ Michael Alram: The history of Eastern Iran from the Greek kings in Bactria and India to the Iranian Huns (250 BC-700 AD). In: Wilfried Seipel (Hrsg.): Weihrauch und Silk. Ancient cultures on the Silk Road. Vienna 1996, pp. 119–140, here p. 136 ff.

- ↑ David Morgan: The Mongols. Second Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford 2007, ISBN 1-4051-3539-5 , p. 117; Michal Biran: Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State in Central Asia. Jerusalem, 1997, p. 51 ff.

- ↑ Denis C. Twitchett, Herbert Franke (Ed.): The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 6: Alien Regimes and Border States. Cambridge 1995, p. 550.

- ^ A b Peter Hopkirk: Die Seidenstrasse , Paul List Verlag, Munich 1986, p. 42.

- ^ Peter Hopkirk: Die Seidenstraße , Paul List Verlag, Munich 1986, p. 48.

- ↑ Birgit Salomon: Sven Hedin on behalf of the Chinese central government. The Silk Road Expedition 1933–1935. (PDF) Diploma thesis, January 2013, accessed on July 30, 2014 .

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Klimkeit: The Silk Road. DuMont-Buchverlag, Cologne 1990, p. 32.

- ↑ Debidatta Aurobinda Mahapatra: The North-South corridor: Prospects of multilateral trade in Eurasia , rbth.com March 14, 2012.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Gabriel Felbermayr: How are you reacting to China's offensive? , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from August 6, 2018; Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: China's New Silk Road. Frankfurt am Main 2017, p. 51ff .; Emanuele Scimia: Trieste aims to be China's main port in Europe , in: Asia Times, October 1, 2018; Willi Mohrs: New Silk Road. The ports of Duisburg and Trieste agree on cooperation , in: Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung of June 8, 2017; Annalisa Girardi: How China Is Reviving The Silk Road By Buying Ports In The Mediterranean , in: Forbes of December 4, 2018.

- ↑ Cf. Felix Lee: Chinas neue Kontinent , in: Die Zeit , from June 28, 2017.

- ↑ See e.g. B. New Silk Road: China beckons with billions , in: Der Standard from May 14, 2017; Finn Mayer-Kuckuk: New Silk Road: China's Private Club , in: Die Zeit from October 10, 2018.

- ↑ See Christian Schütte “Die Balkan-Connection” in Manager Magazin 4/2018, p. 84f.

- ↑ See u. a. Hendrik Ankenbrand “China's New Silk Road” in FAZ on December 27, 2016; Chinese want to invest in the port of Trieste - goods traffic on the Silk Road runs across the sea , in: Die Presse from May 16, 2017; Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: China's New Silk Road. Frankfurt am Main 2017, p. 51ff. See also Dirk Ruppik: Von Löwen und Drachen , in: Deutsche Seeschifffahrt 2/2018, p. 36 ff.

- ^ "China's New Silk Road Stabilizes Muslim Countries" in German Business News from March 13, 2018.

- ↑ Heinrich von Pierer: 100 countries, 900 billion euros investments - Why Germany must not be left out in the mega-project Silk Road , in: Focus from March 19, 2018.

- ↑ See Axel Granzow: Close cooperation between Triest and Duisburg , in: DVZ of June 8, 2017.

- ↑ See "Cerar distributes against coalition partners" in Wiener Zeitung of March 15, 2018.

- ↑ See u. a. Harald Ehren: Partial expansion of the Silk Road , in: DVZ from June 8, 2017; Wolfgang Peiner: Hamburg is facing epochal changes , in: Die Welt from February 17, 2017.

- ↑ Cf. Willi Mohrs: New Silk Road. The ports of Duisburg and Trieste agree on cooperation, in: Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung of June 8, 2017. See also Duisburger Hafen wants to expand business in China , in: Wirtschaftswoche of March 28, 2018.

- ↑ See also “Combined train Trieste-Kiel officially started” in DVZ of February 22, 2017; Frank Behling: DFDS buys Turkish shipping company , in: Kieler Nachrichten of April 12, 2018; Frank Behling: Port train Kiel-Trieste. From the fjord to the Mediterranean , in: Kieler Nachrichten of January 25, 2017.

- ↑ Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: China's new silk road. Frankfurt am Main 2017, p. 59.

- ↑ See Port of Trieste on course for growth: New rail connection to Rostock , in: Der Trend from October 17, 2018.

- ↑ See "Logistics: Lkw Walter starts on a new Adriatic-Baltic route" in Industrie Magazin on October 17, 2018.

- ^ Dradio.de, Das Feature , May 3, 2011, Ghafoor Zamani: Seidenstrasse - Der Heroin-Highway (manuscript) (May 4, 2011).

- ↑ Asia House Foundation: Old Silk Road in a new guise - China's globalization offensive; Supplement to the taz on October 28, 2016