Purple (dye)

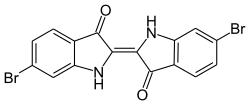

| Structural formula | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

| General | ||||||||||

| Surname | 6,6'-dibromoindigo | |||||||||

| other names |

|

|||||||||

| Molecular formula | C 16 H 8 Br 2 N 2 O 2 | |||||||||

| External identifiers / databases | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| properties | ||||||||||

| Molar mass | 420.05 g mol −1 | |||||||||

| safety instructions | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| As far as possible and customary, SI units are used. Unless otherwise noted, the data given apply to standard conditions . | ||||||||||

Purple (male or neuter - the or that; Middle High German also purper [male or female], Old High German [female] purple [ a ] from Latin purpura , this borrowed from ancient Greek πορφύρα porphyra , "purple snail, purple dye") is called a dye , the was originally obtained from the purple snails (preferably Hexaplex trunculus ) living in the Mediterranean . Its bright color ( crimson ) is also called purple . Chemically, it is 6,6'-dibromoindigo , which is closely related to indigo .

history

The discovery of the coloring effect of purple was ascribed to the inhabitants of the Phoenician city of Tire in antiquity . But it could be proven that as early as 1600 BC In the Minoan Crete was made purple. In the Bronze Age settlement of Coppa Nevigata (near Manfredonia , Apulia ), the extraction of purple from purple snails ( Murex ) has been proven. This probably began as early as the 19th / 18th. Century BC BC, since remains of purple snails were found in considerable numbers (over 1400) in the early layers of the Bronze Age. By far the most relics of purple snails (over 30,000 so far) date from the 15th and 14th centuries BC. BC, which, however, can also be due to research.

According to legend , Heracles , who is equated with the Phoenician Melkart, is said to have stalked a nymph named Tire. When the dog of Heracles bit into a purple snail sitting on a cliff by the sea and its lips turned a beautiful red, the nymph declared that she would not receive Heracles again until he had procured her a dress of this color.

According to Achilles Tatios , a fisherman's dog is said to have bitten into a discarded purple snail. When the fisherman wanted to wash out the supposed wound, he discovered the persistence of the color.

The manufacturing process is most fully described by Pliny .

The snails were caught between autumn and spring. The animals were killed, the hypobranchial gland with the dye precursors removed and immersed in salt for three days. The whole thing heated in water, but not boiled. Then the mass was cleaned from the meat residues. However, the rapidly forming purple dye was not suitable for dyeing. To do this, it first had to be reduced to its leuco form. The fabric (wool, silk) impregnated with the reduced purple color was exposed to light or atmospheric oxygen or both so that an enzyme reaction could change the reduced pale yellow color to the original purple color . The color was supposedly fixed by adding honey. Approximately 12,000 snails are required to produce one gram of pure purple.

In ancient Rome , the purple stripes on the toga were reserved for senators . Later, the Roman emperor and the triumphant wore a toga that was colored entirely with purple during the triumphal procession . In fact, no edict has ever been able to curb the luxury of clothing operated by private individuals with purple. In Rome there were guilds ( collegia or familiae ) of the Purpuraii , in whose hands the capture of the purple snails and the production of purple was. Livy describes the odor of the raw dye as objectionable and its color as similar to that of the stormy seas.

In late antiquity the purple lamys / paludamentum was the privilege and badge of the Roman and Byzantine emperors . The color was also a status symbol for the German emperors , and from 1468 it was the official color of the cardinals . Remarkably, the robes were mostly colored with Kermes as a substitute for the original purple.

Today, purple is only used on traditional church or state-official occasions, for example by the British kings, but the coloring is no longer done with the juice of the purple snail.

chemistry

The structure of purple was determined by Paul Friedlaender in 1909 as dibromoindigo.

The dye 6,6'-dibromoindigo was first chemically synthesized in 1903. The total synthesis of purple took some time after the structure was elucidated. The incorporation of the bromine is directed to the substitution site by the other substituents in the benzene ring. The amino group –NHR is ortho-para-directing, the group –CRO is meta-directing and thus bromine substitution is not thermodynamically favored. Direct bromination of indigo therefore produces 5,5'-dibromoindigo or 5,5 ', 7,7'-tetrabromoindigo (Ciba blue G), which has different color properties due to the π-electron ratios.

use

Nowadays the expensive original dye is rarely used. Mostly it is used for liturgical purposes, such as coloring robes for the Jewish chief rabbinate . It is also used for the restoration of fabrics originally dyed with purple. To date, this dye is the most expensive, it is offered at a price of around 2500 euros per gram.

The purple snail

The marine biologist Félix Joseph Henri de Lacaze-Duthiers found in 1858 that three snails in the Mediterranean produce purple-blue dyes. One species, Murex trunculus (now Hexaplex trunculus ), was identified by him as the source of the blue purple in the Bible ( 2 Mos 26 EU ). In his book Mémoire sur le pourpre (Paris 1859) he dealt with ancient purple dyeing. The snail species Nucella lapillus , which occurs in the Atlantic , also provides the dye.

Purple oxides

Iron oxide pigments , which are produced as a by-product when roasting pyrite to obtain sulfurous acid , are called purple oxides. Brown organic pigments are also often added to them to increase their opacity .

See also

literature

- Hartmut Blum : Purple as a status symbol in the Greek world (= Antiquitas. Series 1, Volume 47). Habelt, Bonn 1998, ISBN 978-3-7749-2875-6 .

- Christopher J. Cooksey: Tyrian Purple: 6,6'-Dibromoindigo and Related Compounds. In: Molecules . 6, 2001, ISSN 1420-3049 , pp. 736-769. (PDF; 302 kB) .

- John Edmonds: The mystery of imperial purple dye. John Edmonds, Little Chalfont 2000 (Historic dyes series 7), ISBN 0-9534133-6-5 .

- Félix Joseph Henri de Lacaze-Duthiers: Mémoire sur la pourpre. Impr. De L. Danel, Lille 1860. (Extrait des: Mémoires de la Société des sciences, de l'agriculture et des arts de Lille ).

- Roland R. Melzer, Peter Brandhuber, Timo Zimmermann, Ulrich Smola: Colors from the sea. The purple. In: Biology in Our Time. 31, 2001. pp. 30-39. (PDF; 802 kB) , doi : 10.1002 / 1521-415X (200101) 31: 1 <30 :: AID-BIUZ30> 3.0.CO; 2-G .

- Reinhold Meyer: History of purple as a status symbol in antiquity. Latomus, Brussels 1970. ( Collection Latomus 116). ISSN 1420-3049 .

- purpura. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der Classischen Antiquities . Vol. 46. Alfred Druckermüller Verlag, Stuttgart, 1959, Sp. 2000-2020.

- Gösta Sanderg: The Red Dyes: Cocheneal, Madder and Murex Purple. Asheville, 1997, ISBN 978-1-887374-17-0 .

- Ehud Spanier: The Royal Purple and the Biblical Blue. Jerusalem, 1987, OCLC 640127534 .

- Gerhard Steigerwald: Purple robes of biblical and ecclesiastical persons as carriers of meaning in early Christian art. Hereditas series . Studies on Ancient Church History 16. Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-923946-43-0 .

- Heinke Stulz: The color purple in early Greek culture, observed in literature and in the fine arts. Teubner, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-519-07455-9 , (At the same time dissertation at the University of Cologne 1990; = contributions to antiquity. Volume 6).

- Herbert Vogler: The traces of early dyeing in the Minoan Empire on Crete . In: German Färberkalender. 88, (1984), pp. 193-206.

- Eva Wunderlich: The meaning of the red color in the cult of the Greeks and Romans. Explained taking into account the corresponding customs of other peoples. Töpelmann, Giessen 1925 (= Religious-historical experiments and preliminary work , 20, 1.) At the same time dissertation at the University of Halle-Wittenberg 1923. Reprint: De Gruyter, 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-158769-1 .

Web links

- Purple by Manfred Breitmoser on purpura.de, accessed on January 9, 2017.

- Purple: Color from the Sea , farbimpulse.de, accessed on September 15, 2004.

- Purple - the color of the emperors (PDF; 50 kB), from kremer-pigmente.de, accessed on January 9, 2017.

- Tyrian purple at chriscooksey.demon.co.uk, accessed January 9, 2017.

- Purple - the color of the emperors from pharmische-zeitung.de, accessed on January 9, 2017.

- Purple in Meyer's Konversationslexikon. Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut Leipzig und Wien, fourth edition, 1885-1892, volume 13, page 471 f.

Individual evidence

- ↑ This substance has either not yet been classified with regard to its hazardousness or a reliable and citable source has not yet been found.

- ↑ Herodotus 4.151.

- ^ Franz Maria Feldhaus : The technology of prehistoric times, the historical time and the primitive peoples. Engelmann, Leipzig and Berlin 1914, p. 843, digitized .

- ^ Claudia Minniti: Shells at the Bronze Age settlement of Coppa Nevigata (Apulia, Italy). In: Daniella E. Bar-Yosef Mayer (Ed.): Archaeomalacology Molluscs in former environments of human behavior. Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archeozoology, Durham August 2002, Oxbow Books, 2005, ISBN 978-1-84217-120-2 , pp. 71-81.

- ↑ Gregory of Nazianz Oratio 4.108.

- ^ Cassiodor Variae 1.2.

- ^ Iulius Pollux Onomastikon 1.45 ff.

- ^ Achilles Tatios Leukippe and Kleitophron 2.11.

- ↑ Pliny Naturalis historia 9.

- ↑ Plutarch Alexander 36.

- ↑ Vitruvus De architectura 7.13.3.

- ↑ Walter Hatto Gross . In: The Little Pauly (KlP). Volume 4, Stuttgart 1972, Sp. 1243 f.

- ^ Gerhard Steigerwald: The imperial purple privilege in the late Roman and Byzantine times. In: Jahrbuch für Antike und Christianentum 33 (1990), pp. 209–233.

- ↑ Paul Friedlander: About the dye of the ancient purple from Murex brandaris. In: Ber. German Chem. Ges. Vol. 42 (1), 1909, pp. 765-770, doi: 10.1002 / cber.190904201122 .

- ↑ F. Sachs, R. Kempf: About p-Halogen-o-nitrobenzaldehyde. In: Ber. German Chem. Ges. Vol. 36 (3), 1903, pp. 3299-3303, doi: 10.1002 / cber.190303603113 .

- ↑ Hans Beyer: Textbook of organic chemistry . Leipzig 1968, p. 632.

- ^ Wilfred M. Morgans: Pigments for Paints and Inks. Trade & Technical, Manchester 1980, ISBN 0-905716-02-7 .