Nordic purple snail

| Nordic purple snail | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Northern purple snails eat barnacles |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Nucella lapillus | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The Nordic purple snail , Nordic stone snail or stone ( Nucella lapillus ) is a snail from the family of the spiny snail (genus Nucella ), which is widespread in the North Atlantic . It feeds on barnacles and clams . In the North Sea , their stocks have declined sharply due to water pollution.

features

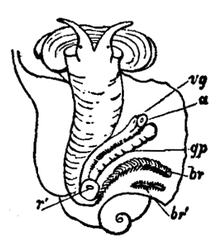

The egg-shaped, pointed, thick-walled snail shell of Nucella lapillus has a conical thread, convex circumferences and a thick, internally serrated lip. It is somewhat smooth, green yellowish to whitish yellowish and often banded with white. In fully grown snails, the shell reaches a length of 3.5 to 4.5 cm, sometimes up to 6 cm. The colors vary a lot. The horny operculum is oval. The snail itself is white or cream-colored with white spots and has a flattened head with two antennae. On both antennae there is one eye each about a third of the length from the base. The base is small and does not protrude over the edge of the case. The proboscis with the mouth and the radula reach about the same length as the housing.

distribution

The northern purple snail occurs in the North Atlantic on the coasts of Europe and North America , for example in the North Sea , off Greenland , Canada and the USA . There are also deposits in the Baltic Sea .

habitat

The northern purple snail lives in the intertidal zone and below to a depth of 40 meters, preferably on rocks.

Life cycle

Northern purple snails can live 6 to 10 years. Like other new snails, Nucella lapillus is segregated. At the age of 1 to 2 years the snails become sexually mature . The male mates with the female with his penis . To mate and lay eggs, many males and females often come together in a sheltered place, and they do not eat during this time. The pairings, which can take place throughout the year, are repeated at intervals, with a few egg capsules being deposited in between. In a clutch, around 10 to 50 capsules sit on a thin membrane that sticks to a rock or a mollusc shell . The bottle-shaped, yellowish egg capsules are stalked, about 7.5 mm long and each contain about 400 to 600 eggs, of which about 25 develop, while the others serve as nursing eggs. Fertility varies. In the White Sea , a female lays 20 to 30 capsules a year, in the North Sea, on the other hand, usually more than 100. The Veliger stage, during which the embryos consume the eggs, is passed through in the capsule. After 4 to 7 months (North Sea or White Sea), small snails with about 2 mm long shells emerge from the capsules.

nutrition

Nucella lapillus eats barnacles and clams . The snail presses its long, thin proboscis between the limestone plates of the barnacles or the shell halves of the mussel or drills them open with the radula . Carbonic anhydrase plays a role in the dissolution of calcium carbonate , which is produced in the accessory boring organ (ABO), a gland in the soles of the snail's feet. The secretion from another gland, the purple-producing hypobranchial gland near the snail's rectum, contains choline esters ( urocanylcholine ), which play a role in numbing the prey and causing muscles to relax. The snail then guides its thin, extendable proboscis through the hole to the meat of the prey. This is pre-digested with enzymes so that the radula does not play a major role in the crushing. The food pulp is slurped up.

Various attempts at prey selection in England indicate that the northern purple snail prefers the barnacle Semibalanus balanoides over barnacles of the genus Balanus . She prefers to eat these barnacles than mussels ( Mytilus edulis ), which she in turn prefers to the barnacles Elminius modestus and barnacles of the genus Chthalamus . She only eats this when the other prey animals are missing. If neither barnacles nor mussels were found in trials in Canada, young common periwinkles were also eaten, while starved purple snails ignored this species in trials in England. For 3 cm long snails, 2 cm long mussels are optimal prey, but from about 4 cm in length the mussels are safe from attacks by Nucella lapillus , so that although it eats the barnacles sitting on the mussel, the mussel is spared. A purple snail can eat about one barnacle per day and one mussel every ten days in summer. It takes about 9 hours to drill a hole in a large barnacle. In many places, Nucella lapillus has a significant impact on the populations of prey species. Newly hatched northern purple snails eat barnacles. Freshly hatched northern purple snails, 1–3 mm in size, have also been observed eating small polychaetes of the species Spirorbis borealis instead of barnacles .

Mussels have a defense strategy that is effective when there are many mussels together by immobilizing the stone snails with the help of their byssus and thus starving them to death. This means that the snails avoid dense mussel banks and tend to attack solitary mussels.

The color of the shell is likely to be influenced by the diet of the purple snail. For example, snails that mainly eat barnacles tend to have white shells, whereas those that mainly live on mussels have mauve to brown shells. For the most part, however, the color is most likely inherited.

Enemies

The main enemies are various birds ( eider ducks , sandpipers and other waders ) and some crabs . The solid shell offers relatively good protection against breakage, while the perforation on the edge of the housing prevents the operculum from opening . Oystercatchers and some crabs are able to crack the hard shell, while eider ducks swallow the snail whole.

Importance to humans

Nucella lapillus , long known by the synonym Purpura lapillus , like other purple snails , forms a milky, choline ester-containing secretion in their hypobranchial gland to numb the prey and to defend it , which it secretes when it is irritated. The secretion turns purple when exposed to light and can therefore be used for dyeing. In Ireland, from the Inishkea Islands in County Mayo, there have been finds of a 7th century dyer's workshop with broken stone snails and dyed textile.

Danger

The northern purple snail stocks in the North Sea have been threatened by tributyltin compounds (TBT), a group of chemicals used for anti-fouling coatings on ships, since the early 1970s . Studies have shown that TBT leads to the formation of male reproductive organs in females of the northern purple snail and other snails (e.g. whelks ). These females affected by the so-called imposex can no longer lay eggs. The northern purple snail is classified as endangered in the North Sea. The snail, which was once common, was no longer found off Heligoland in 2002. According to the German Federal Species Protection Ordinance ( Appendix 1 ), the populations of the North and Baltic Seas are protected.

literature

- JH Crothers (1985): Dog-whelks: an introduction to the biology of Nucella lapillus (L.) (PDF; 5.1 MB) ( Memento from December 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ). Field Studies 6 (1985), pp. 291-360.

Web links

- Fischhaus Zepkow: Family Muricidae - spiny snails

- Ecomare: Northern purple snail (biology and endangerment)

- MarLIN, Biodiversity & Conservation: Dog whelk - Nucella lapillus

- BIOTIC Species Information for Nucella lapillus (English, very detailed and referenced)

- Marine Species Identification Portal: Nucella lapillus (Linné, 1758)

- Underwater World North Sea: Northern purple snail

Individual evidence

- ^ C. Brüggemann: The natural history in faithful illustrations and with a detailed description of the same. Eduard Eisenach publisher, Leipzig 1838. The molluscs. P. 68. The stone. Buccinum (Purpura) Lapillus List.

- ↑ a b Erwin Stresemann (Ed.): Excursions fauna. Invertebrates I. SH Jaeckel: Mollusca. Volk und Wissen, Berlin 1986, DNB 870164724 , p. 133, Die Purpurschnecke , Nucella lapillus (L.).

- ↑ Harvey Tyler-Walters: Nucella lapillus. Dog whelk ( Memento of the original dated February 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Sub-programs (on-line). Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 2007.

- ↑ Louis Charles Kiener : Spécies général et iconographie des coquilles vivantes: comprenant la collection du Muséum d'histoire naturelle de Paris, la collection Lamarck, celle du Prince Masséna ... et les déecouvertes réecentes des voyageurs . Chez Rousseau: J.-B. Baillière, Paris 1835. pp. 101-103. 64. Pourpre à teinture. Purpura lapillus, Lam.

- ↑ JH Crothers (1985), p. 295.

- ^ A b World Register of Marine Species , World Marine Mollusca database: Nucella lapillus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- ↑ Vollrath Wiese: Preliminary list of species of mollusks in the Baltic Sea . House of Nature - Cismar (Malacological Museum)

- ↑ Emil Selenka: The plant of the cotyledons in Purpura lapillus. In: Dutch Zoology Archive. 1, Haarlem 1871. pp. 211-218.

- ^ JH Crothers: Dog-whelks - an introduction to the biology of Nucella lapillus (L.). In: Field Studies. 6, 291-360, 1985, Field Studies Council, 1986 edition, ISBN 978-1-85153-171-4 .

- ^ German translation of the term ABO (accessory boring organ) in: Cleveland P. Hickman, Larry S. Robert, Allan Larson, Helen l'Anson, David J. Eisenhour: Zoologie. 13th edition, translated from the English by Thomas Lazar. German adaptation by Wolf-Michael Weber. Pearson Germany, Munich 2008. 1347 pages. ISBN 978-3-8273-7265-9 , p. 510.

- ↑ Monique Chétatl, Jean Fournié: Shell-Boring Mechanism of the Gastropod, Purpura (Thaïs) lapillus: a Physiological Demonstration of the Role of Carbonic Anhydrase in the Dissolution of CaCO3 . In: American Zoologist. 9 (3), pp. 983-990, 1969, doi: 10.1093 / icb / 9.3.983 .

- ↑ a b Melbourne R. Carriker: Shell penetration and feeding by naticacean and muricacean predatory gastropods: a synthesis . (PDF; 12.5 MB). In: Malacologia. 20 (2), pp. 403-422, 1981.

- ↑ a b J. H. Crothers (1985), pp. 293-301.

- ^ HB Moore: The biology of Purpura lapillus. 2. Growth . (PDF; 2.47 MB). In: Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Vol. 23, pp. 57-66, 1938, doi: 10.1017 / S0025315400053947 .

- ^ Peter S. Petraitis: Immobilization of the predatory gastropod, Nucella lapillus, by ist prey, Mytilus edulis. In: The Biological Bulletin. Vol. 172, pp. 307-314, 1987, doi: 10.2307 / 1541710 .

- ^ HB Moore: The biology of Purpura lapillus. 1. Shell variation in relation to environment . (PDF; 7.73 MB). In: Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Vol. 21, pp. 61-89, 1936, doi: 10.1017 / S002531540001119X .

- ↑ Leonard Hill: Shells: Treasures of the Seas. Translation by Christiane Bergfeld. Könemann, Cologne 1999. 304 pages. ISBN 978-3-89508-571-0 .

- ↑ JH Crothers: On variation in the shell of the dog-whelk, Nucella lapillus (L.) (PDF; 2.45 MB). In: Field Studies. 4, pp. 39-60, 1974, doi: 10.1016 / 0141-1136 (79) 90015-1 .

- ↑ Direct genetic studies are only available for the related Nucella emarginata : A. Richard Palmer: Genetic Basis of shell variation in Thais emarginata (Prosobranchia, Muricacea). I. Banding in populations from Vancouver Island . (PDF; 386 kB). In: Biological Bulletin. 169: 638-651. (December. 1985) demonstrated the inheritance of color, banding and spiral shell sculpture using breeding experiments, JSTOR 1541306 , doi: 10.2307 / 1541306 .

- ↑ JH Crothers (1985), pp. 301-303.

- ↑ Carole P. Biggam: whelks and purple dye in Anglo-Saxon England. In: Anglo-Saxon England. 35, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-88342-9 , pp. 23-55, doi: 10.1017 / S0263675106000032 .

- ^ F. Henry: A wooden hut on Inishkea North Co. Mayo. (Site 3, House A). In: Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 82: 163-178, 1952, JSTOR 25510828 .

- ^ PE Gibbs, GW Bryan: Reproductive failure in populations of the dog-whelk Nucella lapillus, caused by imposex induced by tributyltin from antifouling paints. In: Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Vol. 66, pp. 767-777, 1986, doi: 10.1017 / S0025315400048414 .

- ↑ Beatrice Froese, Barbara Kohmanns (1997): Environmental chemicals with hormonal effects. ( Memento of the original from February 24, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 266 kB), Bavarian State Office for the Environment.

- ↑ Eike Rachor, Alfred Wegener Institute Bremerhaven: Dangerous situation in the busy environment of the North and Baltic Seas - an analysis of the situation ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . (PDF; 2.0 MB), pp. 7–8. 31st German Nature Conservation Day, 17. – 21. September 2012, Erfurt.

- ↑ Appendix 1 of the Federal Species Protection Ordinance