Roman-Indian relations

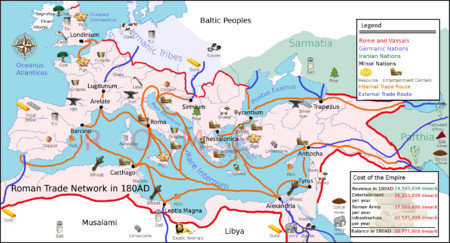

The Roman-Indian relations were numerous connections that maintained the Roman Empire and the Indian subcontinent . The Indian trade was of great importance in this context .

Historical requirements

Building on the conquests of Alexander the Great and the subsequent, Greek-influenced kingdoms , Rome was able to fight the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire under Antiochus III in the Roman-Syrian War (192-188 BC) . expand its political role in the eastern Mediterranean and beyond.

Antiochus III. renounced a large part of its possessions in Asia Minor after the victory of Rome . Attempts by Macedonia to restore the old hegemony led to war. 168 BC The Macedonians were finally defeated under their king Perseus and their kingdom smashed, 148 BC. Finally converted into a Roman province . This is what happened in 146 BC. BC also Greece (from 27 BC province Achaea , previously part of Macedonia) and the new Roman province Africa after the destruction of Carthage , which had regained power before the Third Punic War (149–146 BC) .

The Parthians stood from 141 BC. At the height of their power. Under the successful Parthian king Mithridates II (124 / 123–88 / 87 BC) was 115 BC. Increased use of the Silk Road: A delegation from the Chinese Emperor Han Wudi paid their respects ( Roman-Chinese relations ).

Palmyra played a central role in land transport : From there, caravans with up to 100 camels were taken several times a year to the Parthian Empire, Seleukeia , Babylon , Vologesias , Charax Spasinu and beyond.

The Bubastis Canal was already built in ancient Egypt , but it did not directly connect the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea , but rather led from the Nile Delta via Wadi Tumilat and Lake Timsah to the Red Sea. Emperor Trajan (98 to 117 AD) built a connecting canal from Cairo to the Bubastis Canal around 100 AD and renewed the latter. This canal system, also maintained by his successors, seems to have been used for a long time in trade with the south and east. The waterway to India was made easier by the Trajan expansion and the expansion of the canal system. The resumption of work on the Bubastis Canal and the construction of a new connecting canal, which was built from today's Cairo ( Babylon ) via Bilbeis to the old Bubastis Canal, resulted in faster transport of goods by water. In honor of Trajan, he is known as Amnis Trajanus or Amnis Augustus . Opposite the Ptolemaic city of Arsinoë, Trajan built the fortified port of Klysma ( Cleopatris , later Kolzum ). This repair of the 84 km long Bubastis Canal between the Nile and the Red Sea, begun by Pharaoh Necho II and completed by Darius I , created a continuous water connection from Rome to certain Indian port cities.

The Roman Indian trade was based on the port of Myos Hormos , which, along with Berenike on the Red Sea, had already been the starting point for trade expeditions in the Ptolemaic Empire . With the Trajan Canal, a direct ship connection to the eastern Roman province of Arabia Petraea was created, which simplified the transport of goods. When Trajan died in AD 117, Rome ruled all the ports of the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. Trade from Egypt to the south and east had reached its peak.

Adulis , located in the Aksumite Empire , was an important station for the Roman trade in India, which is why early contacts with the Roman Empire came about . The Roman emperor Aurelian (270 to 275) is said to have received an Aksumite embassy. The emergence of the Aksumite empire can be scheduled for the birth of Christ at the latest. The first mention of the city of Aksum are found in the anonymous Periplus of the Erythraean Sea , which in the mid- first century was n. Chr., And in the Geographike hyphegesis of Ptolemy (around 170 n. Chr.). Already at that time Aksum controlled access to the Red Sea with the important port of Adulis, which enabled the Aksumite Empire to expand into southern Arabia.

Pax Romana

While the eastern part of the overland trade routes to Asia was relatively safe, from 55 BC onwards Conflicts between the Romans and the Parthians, which only began with the first Roman emperor Augustus in 20 BC. BC ( Pax Romana ) were ended. As a result, trade with the Far East increased.

Under Augustus (reign from 27 BC to 14 AD), after the conquest of Egypt, there were increasing demands in the Roman economy to expand trade to India . A hindrance, however, was the Arab control over every sea route to India. The control of the sea trade, which had taken over the importance of the old frankincense route for southern Arabia since the end of the Minean Empire , had now come under Himyar and Sabaean influence. Accordingly, one of the first naval operations under Augustus consisted of the preparation of a campaign on the Arabian Peninsula : Aelius Gallus , Prefect of Egypt , had around 130 transporters built and transported around 10,000 soldiers in 25 to 24 BC. To Arabia. The subsequent march through the desert to Yemen failed, however, and the plans for control over the Arabian Peninsula had to be abandoned. At the turn of the century, the Roman Empire alone is said to have consumed 1,500 tons of the estimated annual production of 2,500 to 3,000 tons of frankincense . The Romans therefore called the area of origin of the precious raw material Arabia Felix - happy Arabia. But the Indian subcontinent also imported the frankincense resin from the frankincense tree.

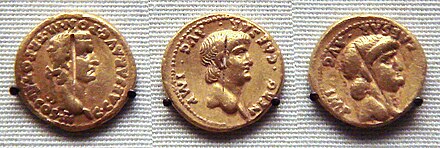

According to historical Roman accounts, messages were exchanged between the Indian king of the Pandya dynasty and the Roman Empire during this Augustan period . Other Indian dynasties were Shatavahana and Kuschana . Several Roman sources describe the visit by ambassadors of the kings of Bactria and India in the 2nd century, probably with reference to the Kushana. A coin of the Roman emperor Trajan was found together with coins of Kanishka the Great in the Ahan Posh Tape monastery . In the Historia Augusta , Emperor Hadrian was mentioned: Reges Bactrianorum legatos ad eum, amicitiae petendae causa, supplices miserunt "The kings of the Bactrians sent him ambassadors to seek his friendship."

Also after Aurelius Victor (138 Epitome, XV, 4) and Appian (Praef., 7) Antoninus Pius , the successor of Hadrian, received some Indian, Bactrian and Hyrcanian ambassadors.

The Chinese historical work Hou Hanshu says: “Precious things from Da Qin [the Roman Empire] can be found there [in Tianzhu or in northwestern India], as well as fine cotton cloths, fine wool carpets, perfumes of all kinds, sugary sweets, pepper, ginger and black Salt can be found. "

A considerable amount of goods imported from the Roman Empire - in particular various types of glassware - were delivered to the summer seat of the Kushan Empire in Greet .

Already in the work Periplus Maris Erythraei (German "Coastal Journey in the Red Sea ") from the 1st century AD, ports, trading conditions, but also the type of flow of goods along the trade routes on the north-east African, Arab and Indian coasts are described. An important prerequisite for this was improved knowledge of the monsoon winds , which allowed safe and, above all, faster passage of the long and dangerous trade route along the coasts. From July to August they sailed along the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden , from then on they sailed to the west coast of India, taking advantage of the northeast winds. In February of the following year, the southwest winds drove back again.

An important stopover was the port of Berenike on the Red Sea (Erythrean Sea). Pearls were also uncovered here, along with many other finds . Some of them come from Arikamedu , the ancient Poduke ( Coromandel coast ), and Mantai on Ceylon ("Indo-Pacific pearls"). Carnelian pearls come from South or West India, garnet and onyx pearls from South India. Processed corals ( corralium rubrum ) were intended for the Indian trade, as were gold glass beads. But also in Arikamedu, Roman artifacts were found during excavations.

The city of Muziris was an important Roman-Indian trading post . It was a flourishing port city in the Chera empire, from which between the 1st century BC There was brisk trade with the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD and in the 5th century AD and is mentioned in numerous ancient Greco-Roman sources (including in the Periplus Maris Erythraei and Pliny the Elder and Claudius Ptolemy ).

Two nautical trade routes are likely:

- from the Gulf of Aqaba through the Red Sea along the south coast of Yemen into the Persian Gulf to Bahrain , and from there on the Iranian south coast to the mouth of the Indus ;

- Another route led from the island of Socotra , an island east of the Horn of Africa and from there directly over the Arabian Sea to the mouth of the Indus.

The Pandya dynasty, like its neighbors, benefited from the regular trade that ran across the southern tip of India to the Roman Empire. The first embassy of the Pandya king was in Tarraco (Tarragona) in the Roman province of Hispania Tarraconensis in the winter months around the year 25 BC. Received. In the year 20 BC BC Augustus received the Indian emissaries again, now on the island of Samos . For the third time a Pandya embassy was sent to the Emperor Augustus in Rome around the year 13 AD.

The early Pandya kings kept Roman soldiers as bodyguards, described in Tamil literature as "dumb strangers with long cloaks and weapons and cruel souls". Luxury goods were traded: shells, diamonds and precious stones, gold articles, spices (especially pepper ), perfumes and especially pearls. But also various animal species such as the blue peacock and Pavo cristatus were shipped to the Roman Empire.

In addition to the Augustan contacts with Indian ambassadors, other Roman emperors, such as Claudius (reigned 41 to 54 AD) and Trajan (reigned 98 to 117 AD) had proven contacts with Indian delegations. During his Parthian War, Trajan was also able to expand his influence on the vassal kingdom of Charakene , a pursuit in the sense of an Alexander imitation . Trajan, one of the militarily most successful emperors - even if his conquests in the east should not last - is said to have regretted his advanced age; otherwise he would supposedly have marched to India like Alexander.

As a result of the imperial crisis of the 3rd century , the Roman-Indian trade relations deteriorated. In late antiquity there were hardly any direct contacts; rather, the trade seems to have been taken over by Persian middlemen from the Sassanid Empire . The trade contacts never broke off completely.

Important ancient ports in India

India was arguably Rome's most important trading partner in Far Eastern Asia. Some ports served as real trading centers, such as:

Important port cities in ancient India |

- Barbarikon : the name of a port near the present-day city of Karachi , Pakistan and significant for trade across the Indian Ocean from the Hellenistic period . The city was under the rule of the Kushana . He is briefly mentioned in the Periplus Maris Erythraei :

- "This river, [the Indus ], has seven mouths, very shallow and swampy, so that they are not navigable, the exception is the one in the middle, where the trading place Barbaricum is on the coast. In front of it is a small island and inland is the capital of Scythia , Minnagara . " Periplus, chap. 38.

- Dwarka : a port facility that no longer exists today, was of great importance for the extensive sea trade in antiquity. This city was also under the rule of the Kushana.

- Barygaza : in the Periplus Maris Erythraei , Barygaza, today Bharuch, is often mentioned as a destination on the monsoon route to cross the Indian Ocean , u. a. from Muza in ancient southern Arabia . For this route, Bharuch was the most important port in North India, it was under the rule of the Shatavahana . Finds of Roman gold and silver coins by the emperors Augustus and Tiberius show passages in the Periplus, according to which Roman coins were imported into Bharuch and exchanged for local currency. At that time, Bharuch was the capital of the satrap Nahapana .

- Muziris : was on the Malabar coast near the mouth of the Periyar River . The city was under the rule of the Chera .

- Poduke : on the site of the village Arikamedu, which is now a little south of today's Puducherry , was between the 2nd century BC. BC and the 2nd century AD an important port, from which there was brisk trade with the Roman Empire . During excavations in the 1940s, large amounts of Roman pottery were found in Arikamedu. The location Arikamedu is identified with the place called Poduke or Poduca , which is mentioned in ancient sources (the Periplus Maris Erythraei and the geography of Claudius Ptolemy ). The city was also part of the Pandya rule and was located on the Gingee River .

The effects of trade relations on the people of the Roman Empire were varied. A Roman trader was able to realize high trading margins by trading in India . For this most Roman merchants had to take out a loan ( mutuum ) before leaving for India . The private creditor ( creditor or mutuo dans ) secured his investment for a trade trip, for example to Muziris in southern India, through a Roman merchant or debtor ( debitor or mutuo accipiens ), by obliging himself to a specific travel route and a specific means of transport to secure his Keeping risks as low as possible. The Roman Empire, for its part, benefited from the tariffs. If the goods arrived in the customs district on the Red Sea, duties of 25 percent - vectigal maris rubri - of the value of the goods were levied. After the transport from Egypt to the remaining parts of the empire, further tariffs were added.

Pliny the Elder stated in his Naturalis historia the Roman-Indian long-distance trade with fifty million sesterces . Shortly before, Strabo described in his Geographica that, starting from Myos Hormos, large Roman naval associations had set out for India, a total of 120 ships where previously only twenty ships had carried out the transport of commercial goods.

See also

- Trajan Canal

- Ships of the ancient world

- Roman Navy

- Economy in the Roman Empire

- List of Roman roads

- Roman-Chinese relations

literature

- Philip DeArmond Curtin and others: Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, ISBN 0-521-26931-8 .

- Hans-Joachim Drexhage : India trade. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 5, Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-476-01475-4 , Sp. 971-974.

- Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund: History of India . CH Beck, Munich 2010.

- David Stone Potter: The Roman Empire at Bay: Ad 180-395. Routledge, London / New York 2004, ISBN 0-415-10058-5 .

- Gary Keith Young: Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC-AD 305. Routledge, London / New York 2001, ISBN 0-415-24219-3 .

- W. Francis: Gazetteer of South India. Volume 1-2. Mittal Publications, 2002, p. 192.

- Grant Parker: The Making of Roman India. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008.

- Eric Herbert Warmington: The Commerce between the Roman Empire and India. 2nd revised and expanded edition. Curzon Press, London 1974.

- Raoul McLaughlin: Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. Continnuum, London / New York 2010, ISBN 978-1-84725-235-7 .

- Anne Kolb: Transport and message transfer in the Roman Empire. Vol. 2 KLIO / supplements. New series, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2001, ISBN 978-3-0500-4824-6 .

- Matthew Adam Cobb: Rome and the Indian Ocean Trade from Augustus to the Early Third Century CE (= Mnemosyne Supplements. Volume 418). Brill, Leiden 2018, ISBN 978-90-04-37309-9 .

- Julia Hansemann-Wenske: Ἐμπόρια. An economic and cultural-historical study of the trade relations between the Roman Empire and India (1st - 3rd centuries AD). Dissertation, University of Kassel 2012 [1]

Web links

- Roman money in India. Bundesbank.de

- Osmond De Beauvoir Priaulx: On the Indian Embassy to Augustus. Vol. 17., Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1860)

- Institute of Archaeological Sciences. University of Bern. Muziris

- Andreas Luther: The sea contact between Rome and India. well-founded. The science magazine of the Free University of Berlin

Remarks

- ^ Schörner: Artificial shipping canals in antiquity. In: Skyllis - Journal for Underwater Archeology (Skyllis) Volume 3, Issue 1, 2000, pp. 38–43.

- ↑ see Lakshmi ( Sanskrit , f., लक्ष्मी, Lakṣmī "happiness, beauty, wealth") is the Hindu goddess of happiness, love, fertility, prosperity, health and beauty

- ↑ Hadwiga Schörner: Artificial shipping channels in antiquity. In: Skyllis - Journal for Underwater Archeology (Skyllis) Volume 3, Issue 1, 2000, pp. 38–43.

- ^ R. Simon: Aelius Gallus' Campaign and the Arab Trade in the Augustan Age. In: Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Vol. 55, Issue 4, 2002, pp. 309-318.

- ^ John E. Hill: Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge., 2009, ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1 , p. 31.

- ^ Roman merchant shipping. Reproduction of the article "Handelsschiffahrt" by Werner Dettelbacher in: Heinrich Pleticha, Otto Schönberger: Die Römer. An encyclopedic non-fiction book on the early history of Europe. Gondrom, Bindlach 1992.

- ^ Gary Keith Young: Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC-AD 305. Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-415-24219-3 , p. 19.

- ^ All roads here lead to Rome again. Indian Express (India). November 6, 2005.

- ↑ Rome mulling funding for Arikamedu project. The Hindu (India). October 18, 2004.

- ↑ Michael Witzel: The old India. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59717-6 , pp. 107-110.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 68,29,1.

- ↑ See James Howard-Johnston : The India Trade in Late Antiquity. In: Eberhard Sauer (Ed.): Sasanian Persia. Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia. Edinburgh 2017, pp. 284ff.

- ^ Sundaresh AS Gaur, Sila Tripati: Evidence for Indo-Roman trade from Bet Dwarka Waters, West Coast of India. National Institute of Oceanography, Dona Paula, Goa, India. In: Int_J_Naut_Archaeol. 35, 117.

- ↑ Shikaripura Ranganatha Rao: The lost city of Dvaraka. National Institute of Oceanography, 1999, ISBN 81-86471-48-0 .

- ↑ Eckart Olshausen, Holger Sonnabend: Stuttgart Colloquium on the Historical Geography of Antiquity, 7, 1999, p. 371.

- ↑ University of Bern, Institute of Archeology ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Krishna Chandra Sagar: Foreign influence on ancient India, p. 132.

- ↑ Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri: A History of South India. OUP, New Delhi 1955 (Reprint 2002), p. 105.

- ↑ On Arikamedu see Vimala Begley: Arikamedu Reconsidered. In: American Journal of Archeology. Volume 87, 1983, pp. 461-481.

- ↑ Customs in the Roman Empire. The customs districts. imperiumromanum.com

- ↑ Pliny, Naturalis historia 6, 101: (...) digna res, nullo anno minus HSD imperii nostri exhauriente India et merces remittente, quae apud nos centiplicato veneant. (...)

- ↑ Janina Göbel, Tanja Zech (ed.): Export hit - cultural exchange, economic relations and transnational developments in the ancient world: Humboldt's Student Conference on Classical Studies 2009. Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4037-9 , P. 79.

- ^ Strabo II, 5, 12.

- ↑ Francesco De Martino : Economic history of ancient Rome , translated by Brigitte Galsterer (original title: Storia economica di Roma antica ). CH Beck, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-406-30619-5 . Pp. 356-376 (356 f.).