Himyar

Himyar ( Old South Arabic myr , Arabic حمير, DMG Ḥimyar ; also Himjar ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in today's Yemen , which existed from around the 1st century BC. Existed until 570 AD. The center was located in the city of Zafar in the Yemeni highlands with the royal castle Raydan at an altitude of 2800 meters about 14 kilometers southeast of today's provincial town of Yarīm . As the last pre-Islamic state in Yemen, the name "Himyar" was generally used for pre-Islamic southern Arabia until the 19th century.

history

The rise of Himyar

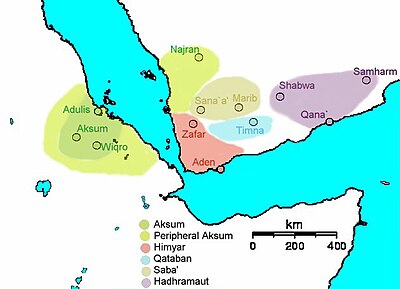

Already in the 5th century BC Himyars settled in the border area between Qataban and Hadramaut . Probably in the 1st century BC The Himyar tribal association in the Yemeni mountainous region gained independence from Qataban. The Himyar era , after which the inscriptions of the Sabao-Himyar Empire were dated, began around 110 BC. The capital was Zafar. Since the new empire was off the Frankincense Route , it expanded to the coast to control sea trade at the exit of the Red Sea. According to Kenneth A. Kitchen , Saba and Himyar were peacefully united in the early 1st century AD. According to Kitchen, this union broke up around 140 AD. In the next few decades, Saba and Himyar were mostly hostile to one another, and even in the Battle of Hurmatum 248/49 no party was apparently able to achieve a clear victory. Around 260/70, Himyar emerged victorious from the power struggle with Saba. Although the Sabao-Himyar empire that had now emerged saw itself as the successor of Saba, it was ruled from the himyar Zafar. As early as 175, the Qataban territory fell completely to Himyar. With the subjugation of Hadramaut (around 300 AD) by Shammar Yuhar'ish , all of Yemen was ultimately united under himyar rule. So the rulers now bore the title "Kings of Saba, Dhu-Raydan, Hadramaut and Yamanat". The additional name Dhu-Raydan refers to the seat of power in Zafar.

Outside the ancestral territories of the ancient South Arabian kingdoms, parallel to the events, the rising Sassanids made hegemonic claims in the Middle East after they had freed their control of the Parthians in AD 224. These should later also take over power in Himyar. At the beginning of his tenure in 275, King Yasir Yuhan'im I drove out the Aksumites who had spread in the Tihama for centuries.

Transition to monotheism

In the first half of the 4th century, Ilān, the Lord of Heaven ( ʾl n bʿl s 1 my n ) appears for the first time in the Himyarian inscriptions . This heralds the transition to monotheism in Himyar , which also took place at the state level at the end of the 4th century. In an inscription by Dharaʾʾamar Ayman, the Lord of life and death, the Lord of heaven and earth, who created everything, is invoked.

In the more recent research it is not doubted that the Himyar lace confessed to Judaism since the late 4th century and also promoted this belief.

Under Abukarib Asad, the empire reached its peak at the beginning of the 5th century. Through campaigns as far as Yathrib / Medina , the influence of the Himyars was extended beyond southern Arabia to large parts of western Arabia. In the following period there were riots by Bedouins . The decline of the old trading centers on Weihrauchstrasse could not be stopped either. The Yemeni highlands, with their extensive rainfall and developed agriculture, became increasingly important for the empire's economy.

Between Ethiopia and Persia

At the beginning of the 6th century there was a conflict among the Himyars between parties who sympathized with Christianity and were allied with the Aksumite Empire , and others who relied on autonomy. With the rule of Maʿdīkarib Yaʿfur, the Christian pro-Ethiopian party initially prevailed.

Yusuf Asʾar Yathʾar , who came to power around 522 and was a representative of the Autonomous Party, underscored his independent position of power by emphasizing his Jewish faith, cracking down on Christians in Himyar. Shortly after gaining power, there was a war against the Christian Aksumite empire, in the course of which Yūsuf had the Ethiopians and Christians living in his country persecuted.

Around 525 the Ethiopian Negus Ella Asbeha organized a military expedition to Himyar, eliminated Yusuf Asʾar Yathʾar, and appointed Sumyafa ʿAshwaʿ his own Himyar vassal, as it was easier for the Aksumites to rule Himyar through a local king rather than on their own. This was ousted in the 530s by Abraha , an Ethiopian general as part of an uprising. Abraha made himself independent from the Aksumite empire in 535 and Sanaa became its capital. In this way he escaped the politically and geographically isolated situation of Zafar, clearly broke with the Himyar tradition and benefited from the economic growth of Sanaa as a pilgrimage center .

Around 570, descendants of the Himyar elite turned to the Persian Sassanids and asked them for assistance in driving out the Ethiopians. In the years 575-576 there was then a Persian intervention that made Himyar a Persian protectorate. After Saif ibn Dhi Yazan, the last Himyarian vassal of the Sassanids, died in 597, they took over direct rule in Himyar and made it a Persian province. During this time of turmoil, Ma'rib was finally abandoned after the last break at the Ma'rib dam (572) ( see the article section: Architectural history of South Arabia ).

List of the kings of Himyar

The following table shows the kings of Himyar after the reconstruction of Kitchen in 1994:

| Surname | Approximate reign | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Mabhad | 115-100 BC Chr. | Son of Abhad, known only as the eponym of the Himjar era |

| Sumhu'ali Dharih III. | 20-5 BC Chr. | known only as the father of his successor |

| Dhamar'ali Watar Yuhan'im | 5 v. Chr. – 20 AD | |

| Yada'il Watar II. | AD 20-25 | |

| Dhamar'ali Bayyin II | AD 25–45 | |

| Karib'il Watar Yuhan'im I. | 45–60 AD | |

| Dhamar'ali Dharih | 70-80 AD | |

| Yuhaqam | 80–85 AD | |

| Karib'il Bayyin III. | 85-90 AD | |

| Nascha'karib Yuha'min I. | 90-100 AD | |

| Rabbsham's Nimran | 100–110 AD | |

| Ilsharah Yahdab I. | 110–125 ad | |

| Watar Yuha'min | 125–135 AD | |

| Sa'jams' Asra | 135–145 AD | |

| Yasir Yuhasdiq | 140–145 AD | |

| Dhama'ali Yuhabirr I. | AD 145-160 | |

| Tha'ran I. | 160–170 AD | |

| ? | ||

| Tha'ran II. Ya'ub Yuhan'im | 220–225 AD | |

| Li'azz Yuhanuf Yuhasdiq | AD 225–230 | |

| Shammar Yuhahmid | A.D. 230–245 | |

| Karib'il Ayfa | A.D. 245–265 | |

| Yasir Yuhan'im I. | A.D. 275–285 | |

| Shammar Yuhar'ish | A.D. 238-300 | finally defeated the Hadramaut |

| Yasir Yuhan'im II. | 300-310 AD | |

| Dhamar'ali Yuhabirr II | A.D. 310-315 | |

| Tha'ran Yuhan'im | AD 315-340 | |

| Malkikarib Yuha'min I. | A.D. 340-345 | |

| Karib'il Watar Yuhan'im III. | A.D. 345-360 | |

| (Hasan) Malkikarib Yu (ha) 'min II. | C 375-410 | |

| Dharaʾʾamar Ayman | C 375-410 | Co-regent |

| Abukarib As'ad | C 410-435 | |

| Hasan Yuha'min | C 436-440 | |

| Sharahbil Ya'fur | A.D. 440–458 | |

| Sharahbil Yakuf | A.D. 458–485 | |

| Ma'adikarib I. Yan'um | AD 485-490 | |

| Abd-kulalum | C 490–495 | |

| Marthad'ilum Yanuf | C 495–505 | |

| Ma'adikarib II. Ya'fur | A.D. 505-517 | |

| Yusuf Asʾar Yathʾar (Dhu Nuwas) | A.D. 517-525 | was defeated by Aksum |

| Simyafa Ashwa | C 525-536 | Aksumite puppet king |

| Abraha | AD 536-570 |

language

- Main article: Himyarian language

The well-known inscriptions from the Himyar Empire are written in a variant of Sabaean, an ancient South Arabic language. The spoken language of the Himjars, Himyarian , on the other hand, is only known through later statements by Arabic authors from the period after Islamization and differed from both Arabic and Old South Arabic.

literature

- Muhammad 'Abd al-Qadir Bafaqih: L'unification du Yémen antique. La lutte entre Saba ', Himyar et le Hadramawt de Ier au IIIème siècle de l'ère chrétienne. Geuthner, Paris 1990, ISBN 2-7053-0494-2 ( Bibliothèque de Raydan 1).

- Iwona Gajda: Le royaume de Ḥimyar à l'époque monothéiste. L'histoire de l'Arabie ancienne de la fin du ive siècle de l'ère chrétienne jusqu'à l'avènement de l'Islam . Paris 2009.

- Jörn Heise: The founding of Sana'a. An oriental-Islamic myth? Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-87997-373-6 (the fourth chapter is particularly relevant).

- Kenneth Anderson Kitchen : Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I: Chronological Framework & Historical Sources. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 1994, ISBN 0-85323-359-4 ( The World of Ancient Arabia Series ).

- Walter W. Müller: Himyar. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 15. Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-7772-5006-6 , Sp. 303-331.

- Walter W. Müller: From ancient Yemen (IX.). Zafar and Himjar. In Yemen report. Vol. 10, 1979, ISSN 0930-1488 , pp. 16-17.

- Norbert Nebes: The Martyrs of Nagrān and the End of the Himyar. On the political history of South Arabia in the early sixth century. In: Aethiopica 11, 2008, pp. 7-40.

- Timothy Power: The Red Sea from Byzantium to the Caliphate: AD 500-1000. The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo 2012.

- Christian Robin (ed.): L'Arabie antique de Karib'îl à Mahomet. Nouvelles données sur l'histoire des Arabes grâce aux inscriptions. Édisud, Aix-en-Provence 1991-93, ISBN 2-85744-584-9 ( Revue du monde musulman et de la Méditerranée No. 60-62).

- Klaus Schippmann : History of the old South Arabian empires. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1998, ISBN 3-534-11623-2 .

- Wilfried Seipel (Ed.): Yemen. Art and archeology in the land of the Queen of Sheba. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998 / Skira, Milan 1998, ISBN 8881184648 .

- Joachim Willeitner: Yemen. Incense Route and Desert Cities. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7774-8230-7 .

- Paul Yule : Himyar. Late Antique in Yemen / Late Antique Yemen. Linden Soft Verlag, Aichwald 2007, ISBN 978-3-929290-35-6 .

- Paul Yule (Ed.): Ẓafār, Capital of Ḥimyar, Rehabilitation of a 'Decadent' Society. Excavations of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1998–2010 in the Highlands of the Yemen. Wiesbaden 2013, ISSN 0417-2442 , ISBN 978-3-447-06935-9

Web links

- University of Heidelberg: Expeditions to Zafar

- Michael Zick: A Christian King in Ancient Yemen . In: Tagesspiegel, December 29, 2010.

- Zafar, Yemen

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d e f Paul Yule, Himyar – Spätantike im Yemen / Late Antique Yemen , p. 45 ff. (See lit.)

- ↑ Kitchen 1994, p. 28 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 49, 189-196.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 39, 226.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 41, 45f.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 226.

- ↑ See Yosef Yuval Tobi: Ḥimyar, kingdom of . In: The Oxford Classical Dictionary Online (5th edition).

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 76-81.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 86.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 97-102.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 111f.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 12.

- ↑ Cf. Gajda 152-156.