Architecture in Yemen

The architecture in Yemen and the art that accompanies it are generally considered to be very rich and independent. From the 3rd / 4th The Arabic - Islamic building culture in Yemen , which began in the 19th century, is closely related to traditional ancient oriental architecture and derives from this in a remarkably conservative manner, so that something special could arise in terms of cultural history . In general, the traditional architecture is attested to a high level in the course of the previous centuries. An essential role for this realization is that a great harmony between the settlement forms and the surrounding landscape could be created almost throughout. This also applies to the overlying Hellenistic , Byzantine and Persian influences of the following centuries, which at the same time formed the basis for Islamic architecture.

Architectural history

Bronze Age finds

Since the early Bronze Age in Ma'layba, in the hinterland of Aden, from the 3rd millennium BC onwards, Until the 13th century BC Traces of settlement known. German and Russian archaeologists uncovered Bronze Age huts and irrigation channels. The Neapolitan, Oriental archaeologists, Alessandro de Maigret and Francesco G. Fedele speak in this context of “ Neolithic ways of life with village culture and pottery from 2000 BC onwards. Chr. "Proved are ovoid or elliptical" huts "and enclosures in the wadi al-'Ush, Ṭayylah and'Ishsh and the Jebel Quṭrān and Sha'ir. Other documented residential buildings come from the Sabir culture, which were excavated in the coastal plain in Sabir . They were made of adobe construction and had inner courtyards. Ceramic shards, false fires and glazed lumps of clay suggest quarters with pottery. In addition, workshops for metal processing and pearl production ( cowrie shells ) were located there. Buildings with organic materials (animal bones) were found at the settlement edges.

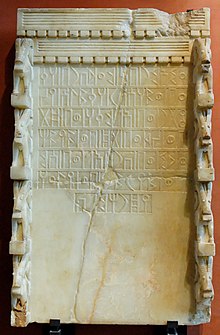

Old South Arabic testimonies

The ancient South Arabian civilization continued at the beginning of the first millennium BC. A. Between 1000 and 700 BC The founding of the important kingdoms Saba , Ausan , Qataban and Hadramaut is located. Despite the steadily growing number of ancient South Arabian archaeological sites and artifacts that have been brought to light, their chronology can at best be sketched in rough outline. Art historical studies also focus on numerous statues and other works of art from the old kingdoms and less on the Himyar Empire, which closes off the ancient South Arabian context and of which hardly any inscriptions exist to illuminate its history . Unambiguous and chronological coordinates cannot be reliably set either for architecture or other artistic creation, because there are only few sources. In particular, there is a lack of systematic excavations, of stratified finds for modern analysis ( e.g. 14 C-dating ) and, in particular , of archaeological works that have been left behind that would have yielded research results that could be used for conclusions.

Sacred architecture

The oldest holy places were represented by a naturally grown stele-like monolith, surrounded by grouped stone settings. Occasionally a dry stone wall enclosed this central point. All later sacred buildings were made of stone, most of which were prepared using the house stone technique that is characteristic of southern Arabia. The resulting temples served as places of pilgrimage and oracle sites. The main features of the increasingly differentiating ancient South Arabian temple architecture include an ascetic language of forms, dominated by cubic and pure stereometry . It is expressed in completely unadorned, abstract-geometric components . In the early Sabaean history, uncovered temple buildings were built , on whose rows of columns , horizontal beams rested as connecting links. The temples were designed as pillared halls with mostly rectangular courtyard dimensions . Only two facilities in Wadi Ḏana (above the Ma'rib dam) near Šakab and not far from the inlet of Wadi Qutūta provide a deeper insight into the early phase of architecture . Research there revealed that the stone pillars in the first-mentioned temple were set extremely regularly, so that a square floor plan was created. The other temple had the peculiarity that one row of pillars stood lengthways, but the other half made an empty field. No models from Arab or Near Eastern architectural history are known for this floor plan idea. According to excavation findings, the interior of the building was also absolutely empty, from which Jürgen Schmidt concluded that it was part of the cult of the dead. The sanctuary was often surrounded by masonry made of lumps of stone, and the area could be entered centrally. The basic principle of the temple construction was characterized by a building that was closed towards the outside and entered centrally. Behind it was a pillar-framed, trend-setting courtyard, at the rear of which was a chambered cella with Adyton . This basic principle was maintained until the late period, which is suggested by the temple in al-Ḥuqqa , which is dedicated to the sun goddess Ḏat Baʿadān (winter sun) . Its construction date is not known, but is believed to be in the 1st century BC at the earliest. Typologically, the temple complexes became increasingly sophisticated in terms of technology and material. From then on, supporting structures enriched the courtyard and propylons with six to eight supports became architectural symbols of dignity. Individual structural elements were highlighted for accentuation and hewn limestone blocks were used. In terms of form, these structures were probably the canonized type of the classical Sabaean temple building.

However, this construction method does not apply to all empires. The buildings in the Minaean Jauf and Qataban differ considerably from those of the Sabaeans in terms of floor plan and room layout. Any tendency towards direction was avoided here, such as the spatial approach to a cella or the orientation of the temple in the peristyle ( Athtar temple of Naschān and Naschq ). The Awwam Temple (near Ma'rib) and the Almaqah Temple in Sirwah show significant evidence of a ground plan structure deviating from these basic principles in their ovoid - apsidial manifestations . Nothing of the actual temple has survived , only the remains of Temenos walls from the two presumably very large complexes have been preserved.

The construction methods changed under the influence of foreign cultures. There is a lack of critical style classifications, so loosely it can be determined that the tie bars distances the temple pillars whose inward inclination and stem - swelling particularly in the Hellenistic , but also Byzantine and Persian changing influences. This can be clearly seen from the temple complex of al-Masajid . This ancient site goes back to the building activities of the Sabaean Mukarrib Yada'il Dharih I , whose reign of Hermann von Wissmann around 660 BC. BC, by Kenneth A. Kitchen, however, around 490-470 BC. Is set. Epigraphically, it provides information about later times and, with floral compositions and foreign style influences, has an architectural ornamentation that clearly does not date from the time the temple was built. There is much to suggest that the facilities were redesigned many centuries later. Another example: Long after it was built, the Athtar Temple of Naschan received decorations such as snake, ostrich, lance, vase, goat and pomegranate motifs.

The scholar Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani narrated in the 10th century that the centers of ancient Yemeni civilization were in full bloom. Arabia Felix was characterized by a penchant for elegance and luxury as well as for arabesque decorations that were omnipresent. Iron, teak , Juniperus , pearls, and precious stones clad the walls of the palaces; Plaster of paris, marble and alabaster are said to have adorned Na'it . Sanaa boasted lofty buildings such as the famous Ghumdan Palace . The palace was founded in Sabaean times by the alleged city founder Sha'r Awtar ; It became famous as the last seat of government of the Himyars, then destroyed by the Aksumites , rebuilt and finally destroyed by the caliphate ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān . The cathedral al-Qualis also set signs of splendor. Ebony , ivory , gold and silver are said to have adorned the pulpit of the cathedral. There are no residues.

Profane architecture and defense systems

For posterity, fortifications, towers and ramparts, foundations of dense building structures and urban wall systems have largely been preserved, since ancient South Arabia consisted of competing and often warring states. The defiant city wall of the Minean city of Naschan was over a kilometer long . The city wall of Baraqish ( Yathill ) reached the extreme height of 14 meters. Ma'rib and Najran were built with barriers so that the settlements were literally enclosed. Even though there were large deposits of wood in the southern mountainous region, no fortifications made from the material are known.

Himyar's capital , Zafar , played a significant role in defensive architecture. According to the descriptions of the scholar al-Hamdānīs , as evidenced by his main work al-Iklīl , the city wall had nine city gates, whose bells announced the arrival and departure of visitors. Old South Arabian Musnad inscriptions as well as other archaeological sources allow a reconstruction of several aspects of Himyar's military strength. Today, the fortifications are largely “ghost walls”, which only reveal that natural stones have been appropriately processed in order to provide an optimal basis for supplementing with masonry stones. It is believed that Aden's irrigation culture with the Tawila cisterns can also be traced back to the Himyar. From today's perspective, the largest known silver mining in the Arabian Peninsula was operated in Ar-Raḍrāḍ ( mine of ar-Radrad ).

Particularly noteworthy is the then Sabaean capital Ma'rib with its dam (there are ruins in Wadi Dhana ), whose water management helped the incense trade to flourish. This ingenious system differed from other irrigation cultures ( Mesopotamia and Egypt ) in that it was possible to release water in cans (periodically). Palaces, castles and temples, such as the Mahram Bilqis or the Throne of the Bilqis (both dedicated to the god of the moon Almaqah ), are mentioned frequently. As in the Minean Yathill or Qarnawu , temples were built in honor of the venerated deities Venus, Sun and Moon, the remains of which are still visible today. Zafar in the kingdom of the Himyars and capital of Yemen until the sixth century AD, Na'it , Bainun and Ghaiman were hardly inferior . Ḥāz still has facades of palace buildings, in which historical inscription and motif stones are set. Many temples had cisterns of various designs in their vicinity . The tendency to abstraction was also evident in the architectural sculpture, in the form of ibex friezes in the entablature zone of temple roofs and bull's head gargoyles on sacrificial basins with corresponding prompts and also in bucrania .

→ Article section: Architecture in Old South Arabia

Hellenistic, Byzantine, Aksumite and Persian influences

Shortly after the turn of the century, old southern Arabia was in the slipstream of the Pax Romana , which protected it from the intrusion of foreign peoples. This brought cultural isolation to the region. The last ancient empire of Old South Arabia, Himyar (1st century BC to 570 AD), at the same time the first to unite the various kingdoms on the territory of today's Yemen, was the first to combine both militarily as was also exposed to culturally increasing attacks from the “outside world”, not least because the shielding Roman imperial era came to an end. Since the Augustan period , Roman architecture was finally merged with Greco-Hellenistic . The building influences of Greece that were effective in Rome (see originally: Magna Graecia ) now united with the architecture of old South Arabia. The late phase of the Himyar era reflected quite eclectic features in its own building industry .

Of the three Greek Orders of the flat came fluted and capitals supporting, Doric element in the repertoire. Hellenistic elements were also found in details of full sculptures and reliefs, which were also based on ancient Mediterranean models. Scientists assume that the “imitation of the Greek way of life”, especially in the architecture of Yemen, must have become established late, namely at the time of the spread of Christianity. This took place with the Aksumites in the 3rd and 4th centuries. At the beginning of the 3rd century Aksum was demonstrably operating on South Arabian soil and formed an alliance with the Sabaean king 'Alhan Nahfan . His son Sha'ir Autar broke this alliance and supported the Himyar king in the expulsion of Aksumite troops from his capital Zafar. Aksumite troops continued to operate in southern Arabia in the following decades. Christian churches arose in Najran and Zafar . Evidently, nothing of it has survived , so that it remains to be seen whether various archived fragments of columns or capitals in Haddah Ghulays deserve sacred or merely profane classification. It is only certain that the components correspond to the Hellenistic architectural style.

The Byzantine architecture Ostrom was a continuation of Roman architecture. The Byzantine Empire , which emerged from the division of the empire in 395 in late antiquity , expanded enormously in the 6th century and encompassed the Arabian Peninsula . Constantinople brought its architectural influences into the country, reinforced by the brief, but archaeologically sustainable, Aksumite occupation of the country. Around 525, Negus Ella Asbeha had reorganized (after previous failure in 518) and eliminated the Sabao-Himyar ruler Yusuf Asʾar Yathʾar in order to replace him with Sumyafa ʿAshwaʿ, a vassal of his own. The Eastern Roman Emperor Justin I had urged him to do this because he wanted to see a reprisal for the mass killing of Christian martyrs in Najran . Since important trade routes ran in the South Arabian region, South Arabia increasingly became the bone of contention for Eastern Roman, Persian and now Aksumite interests (see later: Roman-Persian Wars ).

After the subjugation of the metropolis of Sanaa , where the Himyars had already moved their seat of government from Zafar, the Great Cathedral of Sanaa was built. The churches built under Constantine in Palestine already had two basic building plans: the basilica , an axial building, as found in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem , and the central building , which is found in the octagonal church buildings in Antioch . These building types were incorporated into the cathedral. Greek workers were responsible for their production (according to today's understanding: architects). A Christian center was to be established in Arabia so that the "followers of the pagan pilgrimage rites" could be converted and worship the new faith. The cathedral actually became a famous Christian pilgrimage site, similar to the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. According to legend, this is due to the fact that Jesus Christ prayed at the place where the cathedral was built. It was described extensively and impressively. According to these descriptions, the cathedral stood in the old town of Sanaa. The space around them was free, which in turn was common for the so-called "circumnavigation rites" of the Ethiopians and based on whose inspiration the layout of the complex was designed. The outer walls were reinforced with beams between the stones, which also corresponded to the Ethiopian construction technology. Between two rows of hewn ashlar stones was a layer of triangular frieze stones of different colors. In the contrasts “white-black” to “yellow-white”, the colors ran out against the blue sky. Mosaics, marble, a high alabaster staircase and gilded doors with silver fittings allegedly clad the front. The three-aisled main hall had dimensions of 25 by 50 meters, the columns were made of ebony and other noble woods, a vaulted transept was 12 meters wide. There were many floral and astral mosaics. A domed Martyrion was also to be admired , which is said to have had a diameter of 20 meters. The floor was lined with marble, and there was a shiny alabaster disc in the dome. An iconostasis is said to have stood in front of the altars , surrounded by a multitude of crosses - some with red carbuncles . On closer inspection, the descriptions of the ships and the Martyrion correspond to the blueprint for the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. Initially untouched, in the course of the advanced Islamic period in Yemen the most beautiful mosaics of the cathedral were removed and brought to Mecca because Christianity was increasingly contained. This happened around 684. The cathedral was finally torn down between 753 and 775.

Churches in the sixth century are similar in shape and construction to the capital Byzantine style of Constantinople ("Byzantium"). Motifs of the time were entwined tendrils of grapevines and acanthus motifs , encircling these, Greek crosses .

The Iranian architecture gave her guest appearance in South Arabia in the early 7th century. The Sassanids , specialists in the Iwan building (cf. Taq-e Kisra ), left cultural traces in the country during their brief occupation. Typical examples of their architecture were the wooden dome construction in front of the mihrāb of the " great mosque " of Sanaa as well as numerous types of columns, relief sculptures and capitals .

Yemeni architecture in the Middle Ages (622–1538)

According to the tradition of the 10th century Yemenite universal scholar al-Hamdānī , the first Islamic buildings in Yemen are said to have been built during the lifetime of the Prophet Mohammed . Up to this point in time, Hellenistic and Persian style nuances in particular had influenced the old Arab building tradition. With the Islamic expansion , radically new art emerged in Yemen from the second half of the 6th century . The country adopted Islam and the new civilizational conditions were adapted. The traditional architecture, which had already been syncretized , also socialized with the new influences, so that mosques , domes and minarets began to change the metropolises and baths , bazaars and schools conveyed a new and comprehensive way of life in terms of faith, education and the market. City walls were built to defend against the outside and to pacify the inside. The old town of Sanaa is considered to be the greatest architectural synthesis of the arts of this era . The charm of the thousand and one nights myth seems to have been immortalized in the cityscape to this day . Sanaa's constant capacity for renewal was ultimately able to successfully defy wars, revolutions and destruction. The mosques and schools ( madrasa ) are considered to be the outstanding architecture of Islam in Yemen . Devout foundations had paid for the costs of these schools. Often the madrasa were spatially directly connected to the mosques. Compared to Arab-Islamic mosques elsewhere, those of Yemen differ in their architectural style, floor plans and the choice of building materials.

Early Islamic architecture

Al-Hamdānīs named four mosques that are said to have been built in the time of the Prophet Mohammed. These are the Great Mosque in the old city center of Sanaa, which has been preserved to this day in modified forms, as well as the Farwah ibn Musayk and Jabbānah mosques in the vicinity of Sanaa and the Al Janad mosque in Taizz .

The Al Janad Mosque in Taizz is the oldest mosque in Yemen. It became important because it is said to have been built by a companion of Muhammad, Mu'adh ibn Jabal , and thus became the center of pilgrimages. It pilgrimage so many there that her visit as one of the religious ceremonies lifted to apply. A visit there became part of a pilgrimage to Mecca , which is why a stay in the mosque was equivalent to a visit to the holy places in Mecca. Under the aegis of the Nubian Husayn ibn Salamah (around 1000) the building was renewed and completely rebuilt in stone in 1105 by Muffaḍḍal ibn Abīʿl Baratāt , now with bricks on the south side. Already destroyed again in 1130 by Sulaihid pillage, it was rebuilt under the Ayyubid ruler Turan Shah , brother of the dynasty founder Saladin , in 1184 and was able to retain its essential shape until renovations in 1973/1974 led to fundamental changes. Special features of the mosque were an arcaded inner courtyard, reminiscent of the Ibn Tulun mosque in Fustāt (Cairo), along with two minarets half protruding from the side wings. The epochal changes can be read on the minarets.

The Great Mosque in Sanaa was also originally built by a companion of Mohammed, Farwah ibn Musayk. A mosque was later dedicated to the client outside the city. The Great Mosque must have adjoined the grounds of the Ghumdan Palace, which was destroyed in 632 . A length of the structure of 55 meters is assumed. Renovation work and architectural extensions followed around 707 under the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I. The use of arcades and the design of the light architecture in the hall roof suggest that Byzantine and Sassanid models contributed. Under the following Abbasids , around 753/54 Kufic inscriptions of the Umayyads on the history of the renovation of the building were erased and conversions were made again. Materials from the destroyed Christian Great Cathedral are said to have been brought in. Later floods are said to have severely damaged the mosque (875/76) and at the beginning of the 10th century the mosque was deliberately flooded (by order of an Ismaili leader), allegedly to destroy the unpopular ceiling decorations. It is still known that the Sulaihid queen, Arwa bint Ahmad , had hands on the building in the years 1130/1131. In the absence of archaeological findings, it cannot be said today whether the mosque still contains elements from the past. During construction work in 1972, under project management by Gerd-Rüdiger Puin , very old fragments of the Koran were found.

The Jabbānah mosque was the place for open-air prayer and the feast days of the Muslim year. Allegedly the Prophet Mohammed had ordered this and deliberately set a place outside the city for it. The mosque had a paved courtyard and a mihrab in the wall. Renovations took place at the beginning of the 20th century. While he was overseeing the construction of the Jabbānah mosque, a fourth mosque was built in honor of the Prophet's companion Farwah ibn Musayk himself.

Another mosque from the early days of Islam, the mosque of Shibam Kaukaban, dates from the 9th century . It presented itself enclosed by a mighty stone wall with few openings. Tall stone pillars had wooden support structures for a flat roof. The northern prayer hall was considered a special showpiece. The columns towered from column drums up to the ceiling of the mosque. Magnificent ceilings with richly carved and painted woodwork closed on high. Mention should be made of the Great Mosque of Saada (Mosque of the Zaidites ) in the context of the early churches. A particularly high minaret was a spectacular feature . The Friday mosques of Zabid and Shibam in the Hadramaut also lead to early Islamic traces. In the Aden area, nothing (any longer) has survived from the time of early Islamic culture.

The epochs of the Sulaihids (1047–1138) and Ayyubids (1174–1228)

Djiblah was the capital of the late Sulaihids . In 1088 Sulaihid queen Arwa bint Ahmad built a Friday mosque with an inner courtyard. Clearly be to their Fatimid , the mihrab and line Accessories such as regarding construction type influences calligraphy and decorations. The later grave of kings is also inspired by Fatimids. The prayer hall has a raised central nave that leads to the center of the qibla wall. The arcades that support the ceiling of the main part of the prayer hall are at right angles to this. There are two domes in front of and the inner courtyard. The south corners have two different minarets, the southwest of which is the older and in its current form to the 14th / 15th. Century.

In the old Persian style of the Apadana mosques, the Abas in Asnaf mosque was built in 1126 to accommodate a saint tomb. The models were mosques of the same style in Shibam Kaukaban (9th century) and Sarhah (11th century). The columns had shafts and capitals in the style of a pre-Islamic temple. The Qibla wall bears a pre-Islamic inscription, which is why it is assumed that the place was sacred as early as the ancient South Arabian era. The painted coffered ceiling is of cultural and historical significance. The reconstruction of the mosque was awarded the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004.

The Ayyubid reign in Yemen lasted from 1174 to 1228. In the absence of preserved buildings, it is difficult to trace the question of the significance of their architecture. The Ayyubids were known for borrowing architectural elements from crusader architecture, military architecture and exterior designs, such as gates (portals) and exterior decorations (niches as structural elements, stalactite motifs and polychrome stone compositions). The sacred building itself remained rather conservative as, in contrast to the Shiite dynasty of the Sulaihids, they were more orthodox. The Medresen building was probably important in Yemen . Although hardly any Ayyubid madrasas have survived, some things have been handed down: The first divan with madrasa was that of the Atabeg Sunqur around 1200. It was the madrasa ibn Dahman . The Asadiya Madrasa is still in Ibb today . However, it should be a replica. Remains of Ayyubid work can be found in the brick minarets of the great mosque of Zabid (model for the Rasulid buildings) and in the mihrāb of Ganad in Sanaa.

The epochs of the Rasulids (1228–1454) and Tahirids (1454–1517)

The Rasulid sacred buildings are worth mentioning . Four of them can be found in Taizz, such as the Ashrafiya Mosque and the Muẓaffar Mosque , which is considered to be the oldest of the era. It is still used as a Friday mosque today. It has the largest prayer hall with a length of 53 meters and three large asymmetrically distributed domes in front of the Qibla wall. It contains rich paintings and an unusual structure of the floor plan. The Ashrafiya Mosque was built in two construction phases, beginning in 1295/96 by al-Ashraf I, continued from 1377 to 1400 under al-Ashraf II. The mosque has beautiful vaults . The floor plan follows a sophisticated plan. In the north of the building there is a prayer hall with paintings, which are considered to be uniquely beautiful in Yemen. The mosque forms a broad facade facing the city. A mosque very similar to the aforementioned mosque is the Mutabiyyah Mosque , which was built around the same time between 1393 and 1400. Here an arcade-lined loggia as well as domed porches and benches are to be named. The Madrasa al-Asadiya in Ibb is also typical of the period . The madrasa contains a large niche prayer room and a large central domed room. The real peculiarity is a novelty of the Yemeni cult building, the "breaking of the walls" by means of large doors, windows and arcades, which mostly lead into the souq . The increased supply of light emphasized the colorful wall paintings, which emphasized playful, small-scale and geometric patterns. The floor plans of all the buildings mentioned, as well as their stucco patterns, were taken up in Arabic literature as valuable achievements.

Characteristics and importance of Rasulid architecture

The Rasulids introduced fundamental architectural innovations. The medresen building was spatially subordinate to the adjacent mosque and thus deviated significantly from the educational institutions established in Syria and Egypt. The mosque formed the centerpiece in the center of the complex. The difference to the construction technology of the four-iwan complex in Persia was even more blatant. Opposite the mostly cube-shaped mosques was a flat-roofed hall. Graves of family members were inserted into individual rooms without consuming space. Qibla walls were clearly and rhythmically structured. Completely new is the use of throat , sima and the framing of a portal with applied bars and profiles, as well as multiple passes as decorations at the main entrances. Folding domes over the entrance to the portals were new, as were the use of barrel vaults, and new knowledge of ancient and late antique architectural traditions. Richly decorated mihrāb towers on the qibla wall were new. The most beautiful tower described in Arabic literature is the minaret of the Madrasa of Gubail near Taizz, one shaft section of which is said to have been triangular in plan and the end of which was formed by a pavilion-like dome kiosk. Decorative elements were given new forms: each window in a blind niche was entwined with twin arcades. Facades are finished off with serrated friezes and battlements. Wall paintings, domes, soffits and sometimes walls did the rest with their decorative effects. The character of all these innovations was carried by the two large preserved madrasas, Ghami al-Muẓaffar and Aschrafiya , which were large-scale orders from the Rasulid rulers and represent the character of this type of construction excellently.

Summary of Rasulid innovations in architecture:

- Opening the space as a release from the closed cube ,

- Creation of light as an architectural task,

- Creation of a homogeneous space (distraction from traditional cube construction),

- Courtyard mosque with a multi-aisled haram and surrounding colonnades,

- The ceiling rests directly on the capitals of the column - or it is supported by arcades,

- Coffered ceilings as an ornamental treasure,

- Introduction of (large) windows,

- rich abundance of jewelry (stucco decoration, painting, carving (soffits)).

The mosque-madrasa Amariyyah in Rada'a can be traced back to the Tahirids . This mosque has impressive fronts. Large open staircases and closed pavilions develop the Rasulid architecture further. Tahirid decorations such as splendid stucco ornaments, geometric and arabesque motifs , Kufic and Naschī calligraphies based on the model of the city of Taizz are a highlight of Yemeni building history. Also in the Hadramaut there were worth seeing sacred buildings of the Tahirids.

Post-Tahirid Yemen / The first Turkish occupation (1517–1538)

The mosque complex of al-Bakiriyyah in Sanaa , built in 1597, attained the greatest architectural importance from the first Turkish occupation . Hasan Pasha was responsible as the builder . The location is close to the city's citadel. A square prayer hall with a side length of 17 meters and a central crowning dome characterize the building. Individual - each domed - structures are next to the mosque a portal and a building for ritual ablutions . In addition, in the west of the building there are two burial chambers that were built in the 19th century and also domed . Opposite these stands an exceptionally high minaret in the east. Fine stucco work in the Ottoman style line the interior of the mosque. A marble minbar comes from Constantinople . A free-standing royal divan stands in front of the south wall. This is covered by a platform supported by six porphyry columns for the recitation of the Koran .

Ornate brick minarets (1520–1597)

A number of brick minarets - typical of the architecture of Sanaa - deserve a brief mention, although this is not an epoch. The origin of the named minarets can be found in the Eastern Islamic architecture. It resembles older Central Asian and Persian brick minarets.

In particular, these are the following minarets:

- Al-Madrashah , built between 1519 and 1520, also the earliest dated minaret from the brick era,

- Salah al-Din , built around 1570,

- Al-Bakiriyyah from the time of the first Turkish occupation (1597).

Outstanding buildings of Islamic architecture

Mosques

- Great Mosque of Sanaa,

- Mosque of al-Janad near Taizz

- Mosque of Queen Arwā bint Aḥmad in Djibla (along with the Dār al-ʿIzz palace )

- Zafar Dhi Bin mosque

- Mosque of Imam al-Hadi in Sa'da - with historical tombs and domes

- al-Aschrafiya mosque in Zabid - beautiful fortress (fertile farmland)

- Amiriya Mosque in Rada

- Schibam Kaukaban Mosque

Castles

- Al-Mutahhar Fortress ( Thula )

- Kaukaban Castle

- Castle Hagga

- Al-Sunara Castle (Sa'da) - is considered one of the strongest castles in Yemen

- al-Amiriya ( Rada'a )

- Castle Sumara

- Al-Qahira Castle (Taizz)

- Bayt al-Faqīh (Tihama) Castle

- Burg al-Zaidiya (Tihama)

Architecture and landscape

Building understanding

It is characteristic of the self-image of Yemeni architecture that building projects were for a long time initiated and carried out by the locals themselves. Since the craftsmen only used local building materials, the result was authentic and harmonious settlements. The difficult traffic conditions and tribal feuds were decisive for the local limitations. Slate deposits on Jabal Munhabbih in Sa'da province were only used by the local population in the rainy region because it was not supplied to other mountain regions. Stones from the central highlands did not get into the coastal region. The residential and defense structures of the mountain villages at-Tawīla or al-Mahwit became part of the rocks, so to speak. The construction activities often shaped the landscape. Stones were removed to build houses, exposing fertile arable land for crops and creating cultural landscapes. Localities often emerged as a reflection of the colors of their building material, depending on whether the available volcanic rocks were black, gray or greenish. In many places, villages were built on hills not just for defensive purposes, but to increase crop yields.

Current architecture

Building materials

The urban and rural circumstances of the country lead to the following distinctions:

- In the west of Tihama , construction methods with wood and straw predominate in the north. In the cities one also comes across the use of shell limestone , obtained from coral mining. The transience of this building material makes the old merchants' houses look very dilapidated today. In southern Tihama, mixed construction methods using wood / straw and fired bricks dominate , as in al-Hudaida , Bayt al-Faqīh and Zabid .

- In the mountain Tihama adjoining to the east and the edge steps to the highlands ( western / eastern mountain slope ), however, hewn natural stones dominate the townscape. Stone houses characterize the cityscape of al-Mahwit , at-Tawīla , Manācha , Thula and al- Hajara , for example .

- In the Yemeni highlands ( highland basins and sills ) there is natural stone as well as baked bricks, as well as rammed earth (clay, sand, gravel - in Yemen Zabur or Hibal ).

- In the northeastern desert regions, building methods made of rammed earth (examples: Sa'da and Ma'rib in Jauf ) have prevailed elsewhere, air-dried adobe bricks (such as Shabwat in Hadramaut ).

Industrial cement and Monier steel did not find their way into the building culture of Yemen until the 1960s, but have largely established themselves since then. Sometimes faced with machine-processed natural stone.

Glass for windows has only been used for just over a hundred years. Window openings were mainly closed with wooden shutters ( Roshan ) . Wealthier people within Sanaa contributed to Alabaster disks. These were prepared thinly and resulted in a milky, pleasant room light. Since the introduction of glass, crescent-shaped skylights ( qamarīya ) made of mosaic-like stained glass have become typical architectural decorations.

House types

The building that is traditional to this day has produced a multitude of house types. In most regions, multi-storey towers dominate. Architecturally and structurally, most multi-storey houses are related to one another in such a way that they form a group or a village. This fact takes into account the needs of everyday life and defense. A completed house was thought of in a special way. Construction progress and ultimately the construction success were recorded by calligraphy on a plaque or a carved gate.

Distinctions can be made as follows:

- Sanaa : Four to six-story family houses are typical here. The basement is reminiscent of models from the vestibule . Stables and storage rooms surround the entrance hall. The predominant building material to be found is hewn natural stone. The upper floors are made of burned brick (clay). Remains of kilns on the edge of the old town (still) testify to this. There are windows from the first floor. Upper windows are used for ventilation and decorative purposes.

- Ibb in the governorate of the same name : Here one encounters the construction of the highlands. The houses are regularly four-story. Hewn natural stone also dominates here. From the first floor, the facades are designed with six rectangular and up to 20 semicircular upper windows. Lattice pattern friezes can be found below the edge of the roof.

- Sa'da : Houses in Sa'da have three to four floors. The building material consists of earth and clay paste as well as chaff . Small ventilation windows can be found in the upper area of the building. The bead construction is characteristic here. Each new bead ring that was put on meant a day's work, because it had to harden over a long period of time before the next ring could be put on. To stabilize the structures, the corners were raised, which could tower over the building as battlements.

- Zabid : The building method in this city consists largely of burnt, often plastered, adobe bricks. The houses are low, sometimes one story. The facade is structured by an entrance door and two windows and is often richly decorated inside and outside with ornamental friezes and surfaces. The facades are often whitewashed.

- Region of the North Tihama : Round and rectangular straw huts characterize the picture in the villages. There is a room usually five meters in diameter and seven meters high. The hut has two doors and no windows. The supporting structures consist of wooden poles. The buildings are lined with thinner trees. Hard grass is used as the outer skin of the hut. The interior walls, plastered with clay and manure, are artistically painted.

- Shibam in the central Hadramaut is completely characterized by traditional building. Here is a - strange-looking - compact unit of 500 high-rise buildings. Although built from air-dried bricks, the buildings tower up to 20 meters in height. Many of these buildings are between 100 and 300 years old. The state of construction reveals that regular overhauls are necessary on the building fabric. The roof and the upper facade of the buildings are whitewashed with lime plaster, which protects the clay building from rain.

literature

- Yusuf Abdallah: The past is alive: people, landscape and history in Yemen. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 472-488.

- Salma Samar Damluij: The Valley of Mud Brick Architecture. Shibām, Tarīm & Wādī Ḥaḍramūt. Garnet, Reading 1992, ISBN 1-873938-01-2 .

- Hadi Eckert: Historic Cities in Yemen. In: Yemen Report. Vol. 33, No. 2, 2002, ISSN 0930-1488 , pp. 16-24.

- Ricardo Eichmann , Holger Hitgen : Marib, capital of the Sabaean Empire. In: Iris Gerlach (Ed.): 25 years of excavations and research in Yemen. 1978-2003. = 25 years excavations and research in Yemen (= booklets on the cultural history of Yemen. 1, ZDB -ID 2466587-3 ). German Archaeological Institute, Berlin 2003, pp. 52–61.

- Francesco G. Fedele: The Neolithic Age in North Yemen. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 35-38.

- Barbara Finster: The architecture of the Rasulids. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 237-255.

- Iris Gerlach : The excavations of the German Archaeological Institute Sana'a in the Sabaean cemetery of the Awam temple in Marib. In: Iris Gerlach (Ed.): 25 years of excavations and research in Yemen. 1978-2003. = 25 years excavations and research in Yemen (= booklets on the cultural history of Yemen. 1, ZDB -ID 2466587-3 ). German Archaeological Institute, Berlin 2003, pp. 86–95.

- Iris Gerlach: The archaeological and architectural history studies of the German Archaeological Institute in the Sabaean city complex and oasis of Sirwah (Yemen / Marib province). In: Nürnberger Blätter to archeology. 20, 2003/2004, ISSN 0938-9539 , pp. 37-56.

- Suzanne Hirschi, Max Hirschi: L'architecture au Yémen du Nord. Berger-Levrault, Paris 1983, ISBN 2-7013-0506-3 .

- Volker Höhfeld: Cities and Urban Growth in the Middle East. Comparative case studies on the regional differentiation of recent urban development processes in the oriental-Islamic cultural area (= supplements to the Tübingen Atlas of the Middle East. Series B: Geisteswissenschaften. No. 61). Dr. Ludwig Reichert, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-88226-230-3 .

- Horst Kopp (Ed.): Geography of Yemen. Dr. Ludwig Reichert, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89500-500-2 .

- Tom Leiermann: Shibam - life in mud towers. World cultural heritage in Yemen (= Yemen Studies. Vol. 18). Dr. Ludwig Reichert, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-89500-644-9 .

- Ronald Lewcock: Yemeni Architecture in the Middle Ages. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 181-204.

- Thomas Pritzkat: Urban Development and Migration in South Yemen. Mukalla and the Hadramatic Foreign Community (= Yemen Studies. Vol. 16). Dr. Ludwig Reichert, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-89500-090-6 (also: Berlin, Free University, dissertation, 1999).

- Jürgen Schmidt : Old South Arabian cult buildings. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 81-101.

- Jürgen Schmidt: The Sabaean water management of Marib. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 57-73.

- Peter Wald: Harmony of settlement and landscape. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 388-391.

Web links

- T. Luke Young: Conservation of the Old Walled City of Sana'a Republic of Yemen

- Issa AM Al. Khatani, Suhaib YK Al-Darzi: Old and Modern Construction Materials in Yemen. The Effect in Building Construction in Sana'a. (PDF) Journal of Social Sciences 3 (3) 2007, pp. 138–142

Remarks

- ↑ a b c d Peter Wald: Harmony of settlement and landscape. In: Werner Daum: Yemen. 1988, pp. 388-391.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ronald Lewcock: Yemeni architecture in the Middle Ages. In: Werner Daum: Yemen. 1988, pp. 181-204.

- ↑ Vittoria Buffa, Ma'layba et l'Age du Bronze you Yémen

- ↑ Alessandro de Maigret: A Bronze Age for Southern Arabia. In: East and West. Vol. 34, No. 1/3, 1984, ISSN 0012-8376 , pp. 75-106, JSTOR 29756677 .

- ↑ a b Francesco G. Fedele: The Neolithic in North Yemen. In: Werner Daum: Yemen. 1988, pp. 35-38, here p. 37.

- ↑ Shard hunt in Yemen

- ^ Burkhard Vogt : The Sabir culture and the Yemeni coastal plain in the 2nd half of the 2nd millennium BC. Chr. In: In the land of the Queen of Sheba. Art treasures from ancient Yemen. State Museum of Ethnology, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-927270-41-5 , pp. 61–65.

- ^ Dates according to the Lange Chronologie . For the problems of the Old South Arabian chronology, see the article " Old South Arabia ".

- ↑ For inscription research we refer to: Eduard Glaser , Hermann von Wissmann , Carl August Rathjens , Jürgen Schmidt , Alfred Felix Landon Beeston , Jacques Ryckmans , Walter W. Müller .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Paul Yule : Himyar. Late antiquity in Yemen. = Late Antique Yemen. Linden Soft, Aichwald 2007, ISBN 978-3-929290-35-6 , p. 161 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e Jürgen Schmidt: Old South Arabian cult buildings. In: Werner Daum: Yemen. 1988, pp. 81-101, here pp. 88-98.

- ^ Translated by Walter W. Müller in Werner Daum: Yemen. 1988.

- ^ Hermann von Wissmann : On the history and regional studies of Old South Arabia (= Austrian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class. Meeting reports. Vol. 246, ISSN 0029-8832 = Eduard Glaser Collection. 3). Böhlau, Graz a. a. 1964, pp. 31–32, 262 and 210 (illustration on the card).

- ↑ Samar Qaed: Historic designs: Aden's famed cisterns. August 22, 2013. Retrieved from Yementimes.com on March 29, 2016.

- ↑ Christian Robin: The mine of ar-Raḍrāḍ: Al-Hamdānī and the silver of Yemen. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 129-131.

- ^ Alfred Felix Landon Beeston : Pre-Islamic inscriptions and pre-Islamic languages of Yemen. In: Werner Daum (Ed.): Yemen. Revised new edition. Pinguin-Verlag u. a., Innsbruck 1988, ISBN 3-7016-2251-5 , pp. 102-106, here p. 103.

- ↑ a b c d e Yusuf Abdallah: The past is alive: People, landscape and history in Yemen. In: Werner Daum: Yemen. 1988, pp. 472-488, here pp. 472-482.

- ↑ Adolf Grohmann : Arabien (= Handbook of Classical Studies . Dept. 3, Part 1, Vol. 3: Cultural History of the Ancient Orient. Section 3, Subsection 4). CH Beck, Munich 1963, p. 140 ff.

- ^ Paolo Costa: Antiquities from Zafar (Yemen). In: Annali dell 'Istituto Orientale di Napoli. 33 = NS 23, 1973, ZDB -ID 191316-5 , pp. 185-206.

- ↑ Al-Tabari from a lost manuscript in his work: Churches and Monasteries of Egypt, and some other neighboring countries.

- ↑ On Puin and the research project at the Great Mosque of Sanaa

- ↑ Restoration of Al-Abbas Mosque ( Memento of the original from June 17, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed on August 28, 2015.

- ↑ Umberto Scerrato: Islam. Monuments of great cultures. Ebeling, Wiesbaden 1972, ISBN 3-921195-34-9 , pp. 86-89.

- ↑ a b c d e Barbara Finster: The architecture of the Rasulids. In: Daum (Ed.): Yemen. 1988, pp. 237-255, here pp. 237-252.

- ↑ picture of the mosque .

- ↑ a b Geographical name follows Horst Kopp: Länderkunde Yemen. 2005, pp. 20 and 30.