Islamic art

In Western art history, the term Islamic art denotes the visual arts that have been produced in the areas of the Islamic world since the 7th century under the influence of Islamic culture . Works that are attributed to Islamic art were also created outside the borders of Islamic states. Although the term covers a period of 1400 years and a wide geographical area, Islamic art shows common, characteristic properties in its design, pattern formation and special craft techniques that make it recognizable as such: architecture , calligraphy , Painting , glass art , ceramics , textiles such as knotted carpets , metalwork , objects made of rock crystal and other areas of the fine arts are shaped by the artistic tradition of the Islamic world.

term

The Islamic world represents a highly differentiated large region that looks back on fourteen centuries of a diverse and complex artistic tradition. The term “Islamic art” is catchy, but problematic on closer inspection. Oleg Grabar pointed out that "Islamic" in the sense of an art-historical definition could not be described in religious terms, since Jews and Christians also lived under Islamic rule and created "Judeo-Islamic" or "Christian-Islamic" art. Grabar therefore initially defines the adjective “Islamic” geographically, as the product of a culture or civilization that is predominantly inhabited or ruled by Muslims - comparable to the terms “ Chinese ” or “ Spanish art ”. Since each region of the Islamic world has retained its own artistic traditions and integrated them into art production under Islamic influence, the term “Islamic art” only makes sense if it is expanded through reference to a cultural or artistic epoch or a specific region. As an alternative, he sees the attempt to recognize changes in meaning or changes in form, the “essential inspiration”, in a continuous artistic development. One way to do this could be to prove permanent changes that go back to the influence of Islamic civilization on the art of a certain region or time. While historical events defined "absolute points in time", Grabar introduced the term "relative time" as the point in time at which "a culture as a whole has accepted and changed". The time frame for this process can, in turn, stake out absolute data. Grabar identifies several characteristics by which a work of art can be recognized as “Islamic”: These include its importance in the social context, the typical, non-pictorial ornamentation, and a tension between unity and diversity.

The discussion about a precise definition of the term “Islamic art” has not yet ended. It continues to be seen as problematic and difficult to define. Iftikhar Dadi pointed out in 2010 that the study of "Islamic art" was a construct of Western specialists, an aesthetic theory or rootedness in the tradition of Islamic culture had not been proven. Dadi points out the temporal parallel between the emergence of the western scientific discipline of "Islamic art studies" and the cultural movement of Orientalism . The Muslim modern artists in particular had no interest in “Islamic art”, which they viewed as something in the past. As Dadi shows using the example of seven modern Pakistani artists, they were rather occupied with the search for an identity in the newly created nation states. The modern Muslim artists would have found their artistic roots more in the tradition of Islamic textuality and through their connection to a transnational modern art .

According to Flood (2007), Western art history has placed the art of the Islamic countries in a "revalued past" from which a "living tradition is excluded", thereby denying its "contemporaneity with the art of European modernism".

Mark

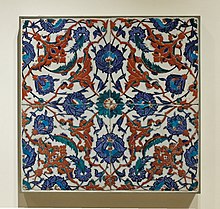

It is typical of Islamic patterns and ornaments that, once they have been developed and understood in terms of their construction, they are used to design various objects made of a wide variety of materials, including in architecture, ceramic art, in embossed leather, carved in wood or ivory, on metal , as well as in textiles. Any object can be recognized as a product of Islamic art through its shape and decoration.

Avoidance of images

Since Islam is not only a religion, but also the guideline for the entire way of life of Muslims, no clear dividing line can be drawn between sacred (religious) and profane (secular) art. The term “Islamic art” makes this close connection clear. Despite the differences in Islamic art of different times and regions, the general tendency towards non-figurative decor strikes the viewer.

Although in sura 59 , verse 24 God is referred to as the (sole) “sculptor”, the Koran does not contain an explicit ban on images . Only with the emergence of the hadith collections were clear restrictions formulated. The handling of such bans varies greatly and is dependent on various factors. In general, however, it can be stated that the pictorial representation in art and architecture is avoided the more

- the building or work of art is closer to the religious area (e.g. the mosque and its inventory),

- The environment (client, artist, ruler) in which a building or work of art is created is more strictly religious,

- more people can access the area in which a building or work of art is located.

The extremes in the attention or neglect of avoiding images can be found in the mutilation of pre-Islamic or non-Islamic works of art on the one hand and the figurative miniature and wall painting on the other. However, even in the latter, people usually shy away from portraying the prophet , or at least let him wear a face veil. In connection with the great meaning of the word, as it were as a carrier of revelation, the avoidance of pictorial representations leads to a dominant role of writing ( calligraphy ) and ornament. An inscription often becomes an ornament itself; geometrically constructed patterns are an unmistakable main element of Islamic fine arts.

symmetry

Symmetry is an expression and fundamental tool used by the human mind to process information. In the pattern formation of Islamic art, the mirror symmetry is particularly important, both in the composition of the entire surface, as well as a single ornament. Davies explains the rules of symmetry in Islamic art in detail using the example of the Anatolian kilim .

template

The use of certain patterns to decoratively organize a surface is characteristic of Islamic fine arts. Patterns are often arranged in different, overlapping levels, so that the design of a surface is perceived differently depending on the position of the observer.

- Geometric patterns are made up of repetitive polygonal or circular partial areas, the arrangement of which comes close to the modern mathematical concept of tiling . Over time, the geometric constructions became more and more complex. They can stand alone as a decorative ornament, a frame for other (floral or calligraphic) ornaments, or fill in the background.

- Arabesques are flat, stylized tendril ornaments made of bifurcating leaves in swinging motion

- In addition to their decorative form, calligraphic inscriptions offer the possibility of introducing another level of meaning, for example by quoting the Koran or poem.

Infinite rapport

In particular, the geometrically constructed patterns can in principle be thought of as continuing into infinity. A delimited area therefore only offers a section of the infinite pattern. Depending on its size, a surface can reproduce a larger or smaller section of infinity, making the pattern appear either small or monumental.

Major epochs

Origins

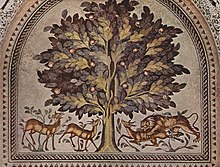

Islamic art did not develop out of itself, but in its beginnings falls back on the artistic traditions of previous or neighboring societies: On the one hand, Roman art , especially in its Eastern Roman- Hellenistic form, the Byzantine art, was formative . The Eastern Roman and Persian Sassanid empires had developed similar representational styles and a comparable decorative vocabulary in the more than 400 years of their joint existence. Artists and craftsmen trained in these traditions continued their work.

Over time, these traditions developed into independent styles of Islamic art. The Arab expansion brought the Islamic society into close contact with the important culture and art of the Persian Empire , which was many centuries older , and the expanding long-distance trade with China and Europe also brought artistic influences with the goods, which were integrated into their own artistic work over time . The centralization of arts and crafts and their centrally organized and controlled development in the court manufactories of the Persian and Ottoman empires , the Mamluk dynasty in Egypt and the factories of the Islamic Mughal rulers of India had a decisive influence on the emergence of a uniformly perceptible Islamic art . Influenced by the art style of the rulers' courts and large city manufactories, but essentially independent, the artistic work of the small rural villages and the nomadic tribes continued.

The Arab Caliphate

A new state began to emerge on the Arabian Peninsula under the religious and political leadership of the Prophet Muhammad (approx. 570–632). His successors were initially men from his followers, the so-called four rightly guided caliphs . Under their rule (632–661), the empire was significantly expanded through the conquest of Iraq , Iran , Syria , Egypt and parts of North Africa. From the years of power struggles after the death of Caliph Uthman (656), the governor of Syria, Muawiya , emerged victorious after the assassination of Caliph Ali (661) . He founded the Umayyad dynasty , which moved its capital to Damascus . The empire was greatly expanded to the west ( North Africa , to almost the entire Iberian Peninsula , parts of southern France ) and to the east ( Khorezmia , Transoxania , Afghanistan and areas on both sides of the Indus ). In addition, campaigns were carried out against the Frankish Empire and Byzantium . The tensions caused by the geographical expansion eventually resulted in an uprising from the eastern provinces. In 750 the Umayyads were overthrown and replaced by the Abbasids , under whom the focus of the caliphate shifted to the east. Baghdad became the new capital ; In the period from 838 to 883, the newly founded Samarra served as a residence. As early as the 9th century, the caliph was increasingly losing its influence and was ultimately little more than the spiritual head of the Muslims. In many areas of the caliphate, the princes ( emirs ) resident there became largely independent and founded their own dynasties, which were only nominally subordinate to the Abbasid Caliph (see the table of Islamic dynasties ).

Art in the Arab Caliphate

Up until the 13th century, the entire Mediterranean region was shaped by a common artistic language of forms and motifs, which was understood in both the Islamic and Christian empires. Early Islamic art under the Umayyads developed on the basis of Hellenistic , Byzantine, and Sassanid traditions. Long- distance trade , which connected flourishing cities with one another, and Islam as the spiritual basis had a unifying effect . From the capital Damascus , impulses went to Spain in the west and to Transoxania in the east. Among their successors, the Abbasids who ruled Baghdad from 750, Iranian and Central Asian influences were given greater weight: the ornaments and motifs were more abstract, and fixed schemes of their arrangement prevailed. With the dissolution of the caliphate, local styles appeared alongside the commonalities promoted by trade, intellectual and artistic exchange.

While sculpture and relief were closely related to pre-Islamic traditions under the Umayyads, the compositional principles peculiar to Islamic art finally prevailed under the Abbasids, such as the complete covering with decoration and the division of surfaces into border and field.

Seljuks, Mongols and Timurids

From the 11th century onwards, tribes and peoples with a nomadic way of life penetrated westward from Central Asia and created new empires on the soil of the caliphate. The conquest of Baghdad (1055) marked the success of the Seljuks in an impressive way. Their sultans left the caliphate as a spiritual office, but could not establish a new universal empire for all Muslims. Local dynasties ( Atabegs ) soon achieved extensive independence, and the Rum Seljuks in Asia Minor founded the Sultanate of Konya .

The invasion of the Mongols in the 13th century was the prelude to further conquests by the Turkic-Mongolian nomadic peoples, which until the end of the 15th century repeatedly led to the formation of great empires, which finally disintegrated into smaller domains.

With Hülegü , a grandson of Genghis Khan , the Mongolian dynasty of the Ilkhan (1255/56 1353) began in Iran . In 1258 Baghdad was destroyed and the last Abbasid caliph, Al-Mustasim, was killed. Only in the battle of ʿAin Jālūt (1260) could the Mamelukes stop the advance of the Mongols. In the middle of the 14th century Timur created a new empire in Central Asia with the capital Samarkand (1369/70), which he quickly expanded with the conquest of Iran , Syria and Asia Minor . After his death (1405) his successors ruled as the Timurid dynasty mainly in Iran, Afghanistan and Transoxania .

Art of the Seljuk period

The formation of an empire by the Seljuks in the 11th century led to a renewed standardization of the formal language, which now also came into contact with East Asian motifs.

With the Seljuks, the motif of human figures became of great importance, especially with subjects related to the veneration of the ruler. In the beginning, pre-Islamic roots were also clearly recognizable in ceramics. The unifying tendencies of imperial art then brought the area-wide ornamentation, the floral and geometrical decoration in the form of tapes and arabesques and finally the varied figurative scenes of the Seljuk period to bear. The enamelled glasses of that time also followed this development, for example with multi-colored scenes.

The close connection between the different areas of Islamic handicrafts is also evident in the metalwork: first of all, the traditions of the Sassanid period were continued almost seamlessly with images such as the “princely rider” or the court scenes , before new animal motifs from Central Asia and China were added in the Seljuk period . The ever more detailed and complicated decor has now been supplemented by a new decorating technique that complements the art of swapping . In swapping, ornamental, figurative or calligraphic decorations are hammered, engraved or etched into the surface of an object made of harder metal . Then the precious metal (silver or gold) is firmly hammered into the groove. According to a simpler process, the wires or plates of the jewelry metal are only knocked on the roughened surface. In the 11th and 12th centuries the Persian province of Khorasan was a center of this decoration technique, in the 13th century the bronzes from Mosul became famous. The hammering of different colored metals into the surface of jugs, bowls or large kettles offered more diverse possibilities to structure elaborate picture fields and borders than pouring , driving and scratching. While the surviving remains of larger woodwork reflect the unifying developments of the respective imperial art, small carvings and ivory work continue to point to the persistence of early Islamic decor for a long time.

Only a few carpets have survived from the Seljuk period. It is very likely that some of the large-format carpets that have been preserved have already been made in specialized factories. Carpets from the 13th and 14th centuries show regular geometric patterns and stylized animal figures.

Miniature painting can be traced back to the Seljuk period. Initially, the representations were relatively small and closely tied to the text. Byzantine , Iranian and Buddhist influences can be clearly seen. In Baghdad at the beginning of the 13th century, a style of painting that was closely linked to the urban sphere flourished , which broke away from the strict forms of the picture structure and preferred subjects other than those of the court.

Art of the Mongols and Timurids

The conquest of the Mongols in the 13th century marked a deep turning point. Since the political and economic environment also changed in the long term for the unconquered areas in the Middle East , the differences between Western and Eastern Islamic art began to deepen despite many similarities. While in the Mameluke regions of Egypt and Syria , in North Africa and Spain the refinement of decorative elements, the more complex geometrical subdivision of surfaces and the extensive renunciation of figurative representations covered all areas of art, the Mongolian and later Turkish waves of conquest brought new influences to the eastern regions from China and Central Asia. Also, the long-distance trade , funded by the empires of Ilchane and the Timurid , made new compositional techniques and motifs for a steady stream, such as dragon and phoenix . In addition to the often best-preserved products from court workshops and their surroundings, urban manufactories gained enormous importance, especially in times of dwindling central power . It was here that forms of commercial art emerged, that is, works produced directly for the needs of wealthy urban classes. In contrast, folk art , often tied to nomadic groups , remained particularly traditional .

Numerous Chinese elements such as certain flower and leaf shapes or bands of clouds found their way into ceramics. Such eastern influences were felt in Islamic art as far as Spain . Although peonies and lotus blossoms in particular betray East Asian influences in princely scenes , calligraphic and non-figurative decorative forms gained more and more importance. In Iran , under the Ilkhans, the Seljuk heritage was initially further developed, but at the same time East Asian flower shapes and peculiarities of figural representation were adopted. Under the Timurids , non-figurative decoration in the form of rosettes , cartouches and medallion shapes became more prevalent again, decoration by engraving and drifting increasingly replaced the inlaid technique . The miniature painting developed in various regional styles and depending on the clients. Over time, the picture became more independent from the text, so that in the end many individual pictures were created.

The late empires

At the beginning of the 16th century there were extensive Islamic states that remained stable for several centuries: the Ottoman Empire , the Safavid Empire and, in northern India, the Mughal Empire . From the 18th century onwards, European powers intervened more and more in the politics of these areas and more or less restricted their independence. The Ottoman Empire had developed from a principality in Asia Minor ( Beylik ) into a powerful sultanate that encompassed large areas of Southeast Europe , the Middle East and North Africa . The Safavids were originally leaders of a Shiite sect who created a new Iranian empire in a relatively short period of time and thus ended a period of varied local dynasties. Babur (1494–1530), a descendant of Timur , finally conquered large parts of northern India after Farghana (1501) and Kabul (1504). The Mughal dynasty founded in this way (from 1526) was only ousted by the British in 1858 .

Art of the late empires

The Islamic art of the early modern period was decisively shaped by the courts of the Ottomans and the Safavids , whereby the more intensive mutual relationships ensured numerous similarities down to the details of the motif development. Out of the need to represent one's own power, under the supervision and control of the courts, an own representative art emerged in highly specialized, division of labor organized court manufactories.

The foreign trade caused substantial Chinese influences in the design of ceramics. Chinese porcelain vessels were collected in great numbers at the rulers of the Ottoman and Safavid empires. The Topkapı Palace Museum still preserves a collection of Chinese porcelain that was also made available to its own ceramic factories as models. In the factories of İznik , for example, plates, bowls and vessels made of delicately decorated ceramics were created based on the Chinese model, and these were further developed into their own shapes and patterns. In line with the richness of color in ceramics, the use of different colored gemstones in metal art increased. In the case of works made of bronze and brass , the inlaid technique was further pushed back by engraving and blackening .

The high-quality products of the court workshops influenced the production of the city manufactories , whose goods were traded on a large scale as far as Europe. Knotted carpets from the Safavid and Ottoman times are among the most perfect products of this handicraft. Under the influence of important artists such as Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, a fundamental change in their design, known as the “pattern revolution”, took place in the 16th century: the principle of the infinite pattern repeat was abandoned in favor of the planar division into central and corner medallions, which we still imagine today from an “ oriental ” or “Islamic carpet”. A few hundred well-known images of oriental carpets in Renaissance painting from the late 13th to the 17th century bear witness to the persistent fascination that the colors and patterns of Islamic carpets had on European artists.

In the Mughal Empire , many influences from non-Islamic art in India found their way into the treasure trove of forms and motifs. The court workshops of the Mughal rulers with their connections to other centers of Islamic art ensured that these elements were integrated into the traditional structures; The trade relations and the associated exchange had a similar effect. Miniature painting is particularly famous , excellent examples of which have also found their way into European collections.

Europe's increasing influence has also been reflected in Islamic art since the 18th century. The borrowings from the Baroque , Rococo or Classicism were, however, subjected to traditional compositional principles. By

- duplication

- Ranking

- Frieze formation

- reflection

- Arrangement as border and field

as well as their connection with traditional patterns, the strange flowers, shell shapes or column motifs fitted into the traditional schemes. The styles created in this way - such as the Turkish Rococo - bear witness to the creative power of Islamic art of the time to absorb and process foreign influences.

The Islamic West

The areas west of the Syrian Desert took a distinctly different path of political development for long periods. The Fatimids (909–1171) founded a Shiite counter-caliphate that had its center in Egypt since the founding of Cairo (969) . The following Ayyubid dynasty (1171–1250) recognized the caliph in Baghdad as the spiritual leader, but like the subsequently ruling Mamelukes (1250–1517), they were completely independent politically. Since 1258 there was an Abbasid (shadow) caliphate at the court in Cairo , which was later to be transferred to the Ottoman sultans .

The only surviving Umayyad Abd ar-Rahman escaped to the Iberian Peninsula and founded a counter-caliphate there from 756, which existed until the 11th century. The subsequent disintegration into many small kingdoms, some of which were fighting against each other ( Taifa kingdoms ) weakened Muslim Spain against the Christian Reconquista . In North Africa , rulership areas emerged mainly from Kairouan , Tunis and Fez , which were united under the Almoravids and Almohads from the 11th to the 13th centuries to form great empires, which also extended to the Iberian Peninsula. Thanks to the efforts of the Almoravids and Almohads, stabilization was achieved again by the end of the 12th century. The last state to exist (until 1492) was the Emirate of Granada under the rule of the Nasrid rulers , where art and culture flourished.

From the 9th to the 11th centuries, the island of Sicily and, at times, parts of southern Italy belonged to the Muslim sphere of influence. Influences from Fatimid Egypt in particular left clear traces, which continued to have an effect well into the 13th century even after the conquest by the Christian Normans .

Art in the Islamic West

Even after the political separation, art in the Islamic West continued to develop in close contact with the eastern regions for a long time. For example, the surviving remains of larger woodwork reflect the unifying developments of the respective imperial art. At the same time, small carvings and ivory work refer to the persistence of early Islamic decor for a long time.

The textiles of the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries from Egypt , Spain and Sicily show the same urge to distance themselves from the natural models of ornaments or to continuous borders and surface-covering patterns as other objects of small art. The numerous animal representations were alienated by frieze-like repetitions, geometric arrangements or finely divided internal drawings.

In Umayyad Spain and Fatimid Egypt, coveted tiles and furniture decorations, combs, cans and boxes were made from ivory. This tradition was continued in Sicily and southern Italy even beyond the Muslim period under the Normans and Staufers until the 13th century.

The conquest of the Mongols in the 13th century, on the other hand, marked a deep turning point. Since the political and economic environment also changed in the long term for the unconquered areas in the Middle East, the differences between Western and Eastern Islamic art began to deepen despite many similarities. While in the Mameluke regions of Egypt and Syria, in North Africa and Spain the refinement of decorative elements, the more complex geometrical subdivision of surfaces and the extensive renunciation of figurative representations covered all areas of art, the Mongolian and later Turkish waves of conquest brought new influences to the eastern regions from China and Central Asia .

A special development under the Mameluk dynasty are the coats of arms , which began in the Ayyubid period and can also be found on enamelled glasses and metal. In the circle of the Mameluke sultans there were also excellent works of the art of exchange .

Modern times

With the orientation of ruling circles towards Europe and the collapse of the great Islamic empires, the fall of the art produced at the courts was sealed. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, only the nomads of Central Asia and the traditional areas around the bazaar as a center of trade and handicrafts preserved important elements of the forms and motifs of Islamic art.

Modern

The modern art of today's Islamic states finds itself in a field of tension between the modern perceived as transnational , the search for an independent national identity in the individual current nation states , and the search of modern Islamic philosophy for an "authentic" ( al-Asala /اصالا / 'Authenticity, originality') shared “Islamic heritage” ( al-Turath /الــتـراث / 'Heritage'). The widespread debate in today's Islamic public also has an impact on the work and perception of the artists themselves and others, and the reception of their works.

Islamic art history as a scientific discipline

The discipline of Islamic art history developed in Western Europe and North America since the end of the 19th century. Alois Riegl and the “Vienna School” he founded did pioneering work . The “Berlin School” of Islamic art history , founded by Wilhelm von Bode and further developed by Friedrich Sarre , Ernst Kühnel , Kurt Erdmann and Friedrich Spuhler , came into being in Germany . Exhibitions in Vienna (1891), the exhibition of the Ardabil carpet in London (1892) and the “Exhibition of Masterworks of Muhammadan Art” in Munich in 1910 aroused public and scholarly interest in Islamic art. Some of the early scholars were important collectors themselves and donated their collections to museums. In Germany, Wilhelm von Bode's donation enabled the Museum of Islamic Art to be founded in Berlin in 1904 .

Museums and collections

- Islamic states

- Museum of Islamic Art (Doha)

- Museum of Islamic Art (Cairo)

- Al-Sabbah Collection in Dar al-Athar al-Islamyya , Kuwait

- Isfahan Decorative Arts Museum

- Iranian Carpet Museum , Tehran

- Europe

- Museum of Islamic Art (Berlin) - currently under renovation (2015)

- Museum of Applied Arts (Vienna)

- Hungarian Museum of Applied Arts , Budapest

- Museum of Applied Art (Frankfurt am Main) - Collection not on display (2015)

- Museum of Arts and Crafts , Hamburg - Newly opened collection of Islamic art in 2015

- Victoria and Albert Museum , London

- Musée du Louvre , Paris

- Benaki Museum , Athens

- United States

See also

- Islamic architecture

- Islamic book art

- Islamic ceramics

- Islamic glass art

- Islamic rock crystal work

- Islamic music

- List of Islamic Art Centers

literature

- Oleg Grabar : The formation of Islamic art . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Yale University Press, New Haven / London 1987, ISBN 978-0-300-04046-3 (English).

- Volkmar Enderlein : Islamic Art. Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1990, ISBN 3-364-00195-2 .

- Janine Sourdel-Thomine, Bertold Spuler: The art of Islam (= Propylaea art history . Volume 4 ). Berlin 1984.

- Joachim Gierlichs, Annette Hagedorn (Ed.): Islamic Art in Germany. von Zabern, Mainz 2004, ISBN 3-8053-3316-1 .

- Robert Hillenbrand: Art and Architecture of Islam. Tübingen, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-8030-4027-2 .

- Lorenz Korn: History of Islamic Art (= bsr. CH Beck Knowledge . Volume 2570 ). CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56970-8 .

- Martina Müller-Wiener: The Art of the Islamic World (= Reclams Universal Library No. 18962) . Reclam, Ditzingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-15-018962-7 .

- Thomas Tunsch: Calligraphy and ornament. Islamic handicrafts . In: rulers and saints. European Middle Ages and the encounter between Orient and Occident (= Brockhaus: The Library, Art and Culture . Volume 3 ). FA Brockhaus, Leipzig / Mannheim 1997, p. 164-168 .

- Wijdan Ali: The Arab Contribution to Islamic Art: From the Seventh to the Fifteenth Centuries. The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo 1999, ISBN 977-424-476-1 .

- State Museums in Berlin, Prussian Cultural Heritage (Ed.): Museum for Islamic Art . von Zabern, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-8053-2681-5 , ISBN 3-8053-2734-X .

- Titus Burckhardt : On the essence of sacred art in the world religions. Origo, Zurich 1955. Strongly expanded new edition as: Sacred Art in the World Religions. Chalice, Xanten 2018, ISBN 978-3-942914-29-1 .

Web links

- Entries on the subject term Islamic art in the catalog of the German National Library

- Search for Islamic art in the German Digital Library

- Search for Islamic art in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum

- Virtual Museum of Islamic Art - Vienna

- The mosque of Sultan Akhmed in Constantinople - in the Pfennig magazine No. 1 of May 4, 1833

- Metropolitan Museum New York - Islamic Art

- Department of Art of Islam in the Louvre: Where Cultures Intermingle

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar : Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250 . Yale University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-300-08869-8 , pp. 3 (English).

- ↑ z. B. the coat Rogers II. , Cf. Oleg Grabar : The Experience of Islamic Art. The so-called Mantle of Roger II, The ceiling of the Cappella Palatina . In: Irene A. Bierman (Ed.): The Experience of Islamic Art on the Margins of Islam . Ithaca Press, Reading et al. 2005, ISBN 0-86372-300-4 , pp. 11-59 (English).

- ^ Oleg Grabar: The formation of islamic art . Yale University Press, Yale (NH) 1987, ISBN 0-300-04046-6 , pp. 2-8 (English).

- ^ Oleg Grabar: What makes islamic art islamic? In: Art and Archeology papers . tape 9 , 1976, p. 1-3 (English).

- ^ Sheila Blair, Jonathan Bloom: The mirage of Islamic art: Reflections on the study of an unwielding field . In: Art Bulletin . tape 85 , no. 1 , March 2003, p. 152–184 , here: p. 157 , JSTOR : 3177331 (English, wordpress.com [PDF; accessed on June 14, 2016]).

- ^ Iftekhar Dadi: Modernism and the art of Muslim South Asia . The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill (NC) 2010, ISBN 978-0-8078-3358-2 , pp. 33-35 (English).

- ↑ Finbarr Barry Flood: From the Prophet to postmodernism? New world orders and the end of Islamic art . In: Elizabeth Mansfield (ed.): Making art history: A changing discipline and its institutions . Routledge, London / New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-415-37235-0 , pp. 31–53 (English, nyu.edu [PDF; accessed June 14, 2016]).

- ↑ a b MD Ekthiar, PP Soucek, SR Canby, NN Haidar: Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art . 2nd Edition. Yale University Press, New York 2012, ISBN 978-1-58839-434-7 , pp. 20-24 (English).

- ^ Dorothy K. Washburn, Donald W. Crowe: Symmetries of culture: Theory and practice of plane pattern analysis . University of Washington Press, Seattle 1992, ISBN 0-295-97084-7 (English).

- ↑ Peter Davies: Ancient Kilims of Anatolia . WW Norton, New York 2000, ISBN 0-393-73047-6 , pp. 40-44 (English).

- ↑ Wijdan Ali: Modern Islamic art: Development and continuity . University Press of Florida, Gainesville (FL) 1997, ISBN 0-8130-1526-X (English).

- ↑ Hossein Amirsadighi, Salwa Mikdadi, Nada M. Shabout (eds.): New vision: Arab art in the twenty-first century . Thames & Hudson, London 2009, ISBN 978-0-500-97698-2 (English).

- ^ KK Österreichisches Handelsmuseum Wien (Ed.): Catalog of the exhibition of oriental carpets in the KK Österreichisches Handelsmuseum . Vienna 1891.

- ^ Edward Percy Stebbing: The holy carpet of the mosque at Ardebil . Robson & Sons, London 1892 (English).

- ^ Friedrich Sarre , Fredrik Robert Martin (ed.): The exhibition of masterpieces of Muslim art in Munich 1910. Reprint of the Munich 1912 edition, Alexandria Press, London 1985, ISBN 0-946579-01-6 .