Islamic glass art

Glassware , from simple everyday objects to valuable vessels, was produced in almost the entire Islamic world. Under the influence of Islamic art , the field of glass production also developed its own language of forms and patterns.

Origins and technology

It is characteristic of Islamic art in general that the enormous religious and socio-political changes had little effect on early art (up to the 9th century). Handicraft techniques and design traditions of the preceding societies initially continued. Art and handicrafts did not change abruptly, but only developed an independent form and shape recognizable as “Islamic” over time.

Glass manufacturing

The Levant , Egypt , Greater Sassanid Persia, and Mesopotamia had a centuries-old tradition of glassmaking . Raw glass was obtained in the form of glass bars on the Palestinian coast between Acre and Tire , as well as in the Egyptian glassworks around the Wādi el-Natrūn near Alexandria and exported for further processing until the 10th or 11th century. The new, uniform social and political order enabled a more intensive exchange of technologies and design ideas, which ultimately led to the development of an “Islamic” glass art.

During the first centuries of the Islamic period, glass makers in the eastern Mediterranean continued to use the Roman recipe, as Pliny the Elder correctly describes it in the Naturalis historia : glass was melted with river sand and baking soda from Egypt. The Egyptian soda was mined at Wādi el-Natrūn , a natural soda lake in northern Egypt. This was relatively pure and contained more than 40 percent sodium oxide and up to 4 percent lime . Soda-based glass can be detected in the Levant until the late 9th century. The furnace smelting furnaces common in the Levant, in which raw glass bars were extracted for trade, remained in operation under Islamic rule until the 10th or 11th century.

After that, baking soda was used less often; Archaeological finds indicate that soda obtained from plant ash replaced the naturally occurring soda and was used throughout the later period. The reasons for this technical change are unclear. It is believed that political unrest in Egypt during the 9th century led to the drying up of soda exports, so that other sources of soda had to be found. This is supported by archaeological finds in Bet She'arim (in today's Israel ), which suggest that experiments with the recipe for the raw glass were carried out there in the early 9th century. A glass bar from a melting vat from this time has a larger proportion of lime than was previously the case and could have been melted from a mixture of sand and vegetable ash. Although the composition of this glass would not have been suitable for use, the finds suggest that Islamic glassmakers at that time combined Roman and Mesopotamian or Sassanid manufacturing traditions to compensate for the lack of mineral soda. The use of vegetable ash, especially obtained from salt plants , which were abundantly available due to the climatic conditions in the Middle East, was well known in Persia and Mesopotamia. Without a doubt, it didn't take the glassmakers in the Middle East long to learn to use recipes made with vegetable ash.

Glass processing

Blow

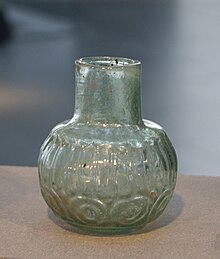

In the early Islamic period, glass was processed using the same techniques that were known before. Glass was blown with the help of a glassmaker's pipe , either freely or in a mold ( model ) so that the inside pattern of the model can be seen on the outside of the glass. The technique of "optical glass blowing" combines the two techniques in that the glass body was first given a shape with the help of a model, and the glass was then blown out freely. In both Iran and Egypt, reusable, two-part folding models were known; glass made in this way has fitting seams. Pinching the fitting seams with pliers is also very typical of Islamic glass art.

Applications and glass tailoring

The placing of drawn glass ribbons on a vessel comes from the Roman tradition, while glass cutting comes from Sassanid art. Glass cutting reached an early peak during the 9-11th centuries. Century, while the art of drawn decorations from molten glass was perfected from the 11th century, during the Seljuk period.

The art of relief cutting probably emerged from the stone cutting art of antiquity. Precious cut gemstones, gems and cameos were made by the ancient Egyptians , Persians , Assyrians and Greeks . Precious rock crystal objects were made using the same technique, especially on behalf of the Egyptian Fatimid rulers during the 9th-11th centuries. Century. While the relief tailoring is performed on the cooled glass, heated, flexible glass threads can be applied to a glass body with the technique of glass application, or patterns, handles or borders can be attached with melted glass threads.

Colors and surfaces

Completely colorless, transparent glass has only existed since discoloration techniques became available. In earlier times, as in Islamic glass art, the glass mass used was only approximately colorless and usually had a yellow, green or blue tinge. Colored glass in manganese red, green, or blue was popular and common. The surface of many surviving Islamic glasses has corroded from being stored in the ground for a long time , giving them an iridescent surface that was not intended, but still appears attractive in our eyes. Only in a dry climate, or if the items have been carefully stored over time, the glassware is preserved unchanged.

Luster colors

Another technique, the use of lustrous coatings on glass is brought especially with the early Islamic period in combination, and was probably in the Islamic period in Fustat developed, although their origins possibly as early as the Roman or Islamic prior art of the Egyptian Copts to search are. Glass vessels were colored with copper and silver pigments as early as the 3rd century BC, but the real luster technology was only developed sometime between the 4th and 8th centuries AD. For this purpose, copper and silver pigments are applied to the glass. Using special firing techniques, the metallic ions bond with the elements contained in the glass and create a metallic sheen that is completely bound to the vessel. Luster coloring is one of the key technologies in glass production, which continued to develop during the Islamic period and not only spread throughout the entire geographic area, but could also be used on other materials such as ceramic glazes .

Marbling

Marbling is a technique of thread casting, with the help of which an object is covered with strands of opaque glass in various colors. The glass strand is warped at regular intervals so that it runs in a characteristic wave shape. The object is then rolled on a plate made of stone or iron until the colored glass strand is firmly worked into the glass body and connected. This technique, which was used to make a wide variety of objects from bowls and bottles to chess pieces, was introduced around the 12th century, but is actually a resumption of a much older technique of glass working that lasted until the late Bronze Age in Egypt goes back.

Enamelling

Enamelling , also a very old technique, was firstdemonstratedin the Islamic world in the 12th century in Ar-Raqqa, Syria,and spreadto Cairoduring the Mamluk rule . Two different techniques were used, which indicates at least two different production centers. The objects consist of an almost colorless, often slightly honey-tinged glass, onto which ground glass mixed with different color pigments is applied, which is then melted at lower temperatures. Enamelled glassware was very popular and was traded in the entire Islamic world as well as Europe and China. The Mongol invasions since the 13th century likely brought this tradition to a standstill.

gilt

At that time, gold plating was done by applying small amounts of gold to a glass body and baking it in at a low temperature. The technique comes from Byzantine art . Gilding was often combined with enamelling . After blowing (mostly optical), the workpiece first had to cool down gradually before a painter applied the multicolored enamel mass together with the gold. The gold enamel mass was firmly attached to the workpiece by means of controlled heating without the workpiece itself melting again. This complicated manufacturing process required great craftsmanship. Until the conquest of Syria by Timur, Aleppo and Damascus were the centers of gold enamel production in Syria.

development

Early Islamic glass art: mid-7th to late 12th century

The early Islamic glass industry coincides with the rise of the Umayyads , the first Islamic ruling dynasty. With the rise of the Abbasid caliphate , the capital of the Islamic world was moved from Damascus in the Levant to Baghdad in Mesopotamia . In the period that followed, a more Islamic style of expression appeared and replaced the classic design tradition.

Glass production during this period was concentrated in three main regions. The Eastern Mediterranean retained its centuries-old role as the center of glass production. Excavations in Qal'at Sem'an in northern Syria , Tire in Lebanon , Bet She'arim and Bet Eliezer in Israel , as well as in Fustāt , ancient Cairo , have revealed evidence of glass smelting everywhere, such as glass vessels, raw glass bars, and smelting furnaces. Robert Brill was the first to use lead isotope analyzes of the glass finds from the Serçe Liman shipwreck to detect glass that was produced in Anguran, north of Tehran .

Large quantities of glassware from the early Islamic period were found in the Persian cities of Nishapur , Siraf , and Susa . Numerous melting furnaces prove that Nischapur and Siraf were important production centers. Excavations in the Mesopotamian Samarra , the short-term and then abandoned capital of the Abbasid caliphs from the middle of the 9th century brought large numbers of glassware to light, as did research in al-Madā'in (the former Seleukia Ctesiphon ) and Ar-Raqqa ( on the Euphrates in today's Syria ) that glass was made in these regions. Unless glass-making waste or furnaces are also found in one location, it is difficult to establish that a given location not only used glass, but also manufactured it. In addition, the glassmakers did not always stay in one place during the Abbasid era. In addition, glassware has been traded on a large scale, so glasses of different origins are widely found. Their design was also standardized and increasingly approached the emerging common “Islamic” style.

With the rise of the Seljuks , technology, style, and trade remained largely unchanged. The skills of Islamic glassmakers continued to develop during this time. However, since only a few glassware are signed or dated, it is seldom possible to assign a specific piece directly to a specific place of manufacture. This is usually done by stylistically comparing a glass product with other pieces from the same period.

Middle period: late 12th to late 14th centuries

This period is considered to be the "Golden Age" of Islamic glass art. The Persian Empire , together with Mesopotamia and at times parts of Syria , came under the control of the Seljuks and later the Mongols, while the Ayyubid and Mamluk dynasties were able to maintain their rule in the eastern Mediterranean . For the first time, the Middle East came into closer contact with Europe through the Crusades . For unknown reasons, glass production in Persia and Mesopotamia came to an almost complete standstill. In the late 12th century, stained glass can still be found in Central Asia, for example in Kuva in what is now Uzbekistan .

However, glass production in Syria and Egypt continued. The objects found in places like Samsat in southern Asia Minor , Aleppo and Damascus , Hebron in the Levant , and Cairo justify the designation as the "Golden Age". Multicolored design techniques such as marbling, enameling, and gilding reached a climax while glass cutting and luster coloring seemed to go out of style. Traditional vessel shapes continued to exist, new ones were invented, which are among the highlights of Islamic glass art. There was a great variety of types, recurring shapes were rod glasses, wash bottles (“ qumqum ”), larger bottles and, above all, mosque lights.

The more intensive contact between the Middle East and Europe is proving to be important for glass art. Gilded and enamelled goods first came to Europe with the Crusades. Raw materials such as vegetable ash were exported to Venice in large quantities , thus enabling the local glass industry to emerge. In Venice, the technique of enamelling was finally taken up again.

Late period: 15th to mid-19th century

The late period is dominated by three major realms and territories of the glass production: the Ottoman Empire in today's Turkey , the kingdom of the Safavids - and later the Zand- and Qajar dynasty in Iran and the Mughal Empire in northern India. During this period, Islamic glass art was increasingly influenced by European glass production, which developed particularly in Venice , in the 18th century in Bohemia and in the Netherlands . The production of fine glasses in high quality came to an end in Syria and Egypt after the court manufactories were no longer sponsored and promoted. Glass was only made in India, often based on European models. Simple everyday objects made of glass continued to be produced.

Historical documents and reports like the Surname-i Hümayun prove the glass production and the existence of a special glassmaker's guild in Istanbul , as well as in Beykoz on the Bosporus coast , in the Ottoman Empire . The glassware in these centers was more of an everyday item with no artistic significance and was stylistically based on European products. In the Persian Empire , the first evidence of glass production after the Mongol storms did not appear again until the Safavids in the 17th century. During this time there were no significant technical or decorative changes. Bottle and jug shapes with simple applications or ribbon decoration are common and are associated with wine production in Shiraz .

On the other hand, in the glassmaking of the Indian Mughal Empire, the tradition of enamelling and gilding from the middle period revived, as well as the tradition of glass cutting, which was widespread in Persia during the first Islamic centuries. Glass workshops and factories were initially located near the capital Agra , in the east Indian city of Patna, and in the west Indian province of Gujarat , with others in other west Indian regions in the 18th century. New shapes were created using the old techniques, including the bases of water pipes ( nargileh ). Square bottles based on Dutch models, decorated with enamel and gilding in Indian patterns, are also of importance for Mughal art. They were made in Bhuj , Kachchh and Gujarat. Ethnological studies of today's glass production in Jalesar show that the glass furnaces are technically very similar to the early Islamic tank furnaces of the Levant. Although of different shapes (angular in India, round in Bet She'arim), they show the impressive continuity of glass production in the Islamic world.

Glassware and its function

The diverse functions and the sheer quantity of the material preserved show the importance of glass production as an independent, highly developed technology of the Islamic world and as a medium of Islamic art.

Utility glass

Glassware served a variety of functions. Since the raw materials were cheap and easily available, many everyday objects were made of glass without any particular artistic intention. This also includes window glass. Utility glass in all its variants was so cheap that the glass containers for certain goods were given to buyers free of charge. Weight stones made of glass, provided with an official seal, weight information and year of manufacture, fulfilled the function of calibration weights . With them the weight of coins and weights could be determined very precisely. Such calibration weights have been particularly important in Egypt since the early days.

Glass was excellently suited for lamps because its transparency on the one hand dampened the light and on the other hand could also give color to the light through its coloring. Lamps for standing or hanging, with wick holders or separately hanging oil containers are known. Drinking vessels were in the form of simple cups, rods or cups are common. Characteristic of Islamic glass art are jugs or bottles with narrow necks, from which the liquids contained could not evaporate too quickly, as well as "tooth bottles", shaped like a molar, for storing small amounts of precious ointments and essences. Ink glasses , qumqum or injection bottles and vessels that are related to Islamic science and medicine, such as alambics or cupping heads, are also particularly significant . Small statuettes as well as jewelry such as bracelets and beads were also made from glass. The bracelet beads in particular are an important archaeological tool for dating sites in the Islamic world.

Artistic glass products

Artistically designed glass was mostly created on behalf of the caliph or other high-ranking personalities who had both valuable consumer goods and particularly valuable art objects made from glass. Typical of the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods are the images of coats of arms, especially on mosque lights, which were made to decorate the newly built mosques in Syria or Egypt. In the context of the light verse of the Koran , these lamps performed a particularly honorable service.

Scientific research

Research into Islamic glassmaking and glass art has received limited attention compared to other aspects of Islamic culture. The work of the art historian Carl J. Lamm (1902–1987) is an exception. Art history not only owes him the discovery of some of the oldest preserved knotted carpets in the world in Fustāt. Lamm also cataloged and sorted the glass finds from important sites of Islamic culture, for example Susa in Iran, or Samarra in Iraq.

One of the most important discoveries for research into Islamic glass art was the discovery of a shipwreck near Serçe Liman on the Turkish coast, dated to around 1036 AD. His cargo consisted of broken vessels and broken glass from Syria, the analysis of which with the help of modern methods such as lead isotope analysis provided important information about the production sites and spatial distribution of glassware. Most of the scientific research was devoted to the stylistic analysis and classification of the patterns. Research into technological aspects, as well as consumer goods as an important medium in everyday culture, is still pending, although the majority of the glass objects were intended for everyday use.

Web links

literature

- F. Aldsworth, G. Haggarty, S. Jennings, D. Whitehouse, 2002: Medieval Glassmaking at Tire. Journal of Glass Studies 44, SS 49-66.

- Barkoudah, Y., Henderson, J., 2006: Plant Ashes from Syria and the Manufacture of Ancient Glass: Ethnographic and Scientific Aspects. Journal of Glass Studies 48, pp. 297-321.

- A. Caiger-Smith, 1985: Technique, Tradition and Innovation in Islam and the Western World . New York, New Amsterdam Books.

- S. Carboni, 1994: Glass Bracelets from the Mamluk Period in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Journal of Glass Studies 36, pp. 126-129.

- S. Carboni, 2001: Glass from Islamic Lands . London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

- S. Carboni and Q. Adamjee, 2002: Glass with Mold-Blown Decoration from Islamic Lands . In: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

- O. Dussart, B. Velde, P. Blanc, J. Sodini, 2004: Glass from Qal'at Sem'an (Northern Syria): The Reworking of Glass During the Transition from Roman to Islamic Compositions . Journal of Glass Studies 46, pp. 67-83.

- K. Erdmann , 1963: 2000 years of Persian glass . Exhibition in the Städtisches Museum Braunschweig from June 19 to September 1, 1963. Braunschweig: Waisenhaus-Buchdruckerei u. Publisher, 1963

- IC Freestone, 2002: Composition and Affinities of Glass from the Furnaces on the Island Site, Tire . Journal of Glass Studies 44, pp. 67-77.

- IC Freestone, 2006: Glass Production in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic Period: A Geochemical Perspective. In: M. Maggetti and B. Messiga (eds.): Geomaterials in Cultural History . London: Geological Society of London, pp. 201-216.

- IC Freestone, Y. Gorin-Rosin, 1999: The Great Slab at Bet She'arim, Israel: An Early Islamic Glassmaking Experiment? Journal of Glass Studies 41, pp. 105-116.

- W. Gudenrath, 2006: Enameled Glass Vessels, 1425 BCE - 1800: The Decorating Process. Journal of Glass Studies 48, pp. 23-70.

- Y. Israeli, 2003: Ancient Glass in the Israel Museum: The Eliahu Dobkin Collection and Other Gifts. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum.

- G. Ivanov, 2003: Excavations at Kuva (Ferghana Valley, Uzbekistan) . Iran 41, pp. 205-216.

- D. Jacoby, 1993: Raw Materials for the Glass Industries of Venice and the Terraferma, about 1370 - about 1460. Journal of Glass Studies 35, pp. 65-90.

- M. Jenkins, 1986: Islamic Glass: A Brief History . Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. JSTOR, pp. 1-52.

- J. Kröger, 1995: Nishapur: Glass of the Early Islamic Period . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- CJ Lamm, 1928: The Glass of Samarra: The Samarra Excavations. Berlin: Reimer / Vohsen.

- CJ Lamm, 1931: Les Verres Trouvés à Suse . Syria 12, pp. 358-367.

- MG Lukens, 1965: Medieval Islamic Glass. 'Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 23.6. JSTOR, pp. 198-208.

- S. Markel, 1991: Indian and 'Indianate' Glass Vessels in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Journal of Glass Studies 33, pp. 82-92.

- R. Pinder-Wilson, 1991: The Islamic Lands and China. In: H. Tait (Ed.): Five Thousand Years of Glass . London: British Museum Press, pp. 112-143.

- T. Pradell, J. Molera, AD Smith, MS Tite, 2008: The Invention of Luster: Iraq 9th and 10th centuries AD. Journal of Archaeological Sciences 35, pp. 1201-1215.

- S. Redford, 1994: Ayyubid Glass from Samsat, Turkey. Journal of Glass Studies 36, pp. 81-91.

- GT Scanlon, R. Pinder-Wilson, 2001: Fustat Glass of the Early Islamic Period: Finds Excavated by the American Research Center in Egypt 1964-1980 . London: Altajir World of Islam Trust.

- R. Schick, 1998: Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: Palestine in the Early Islamic Period: Luxuriant Legacy. Near Eastern Archeology 61/2, pp. 74-108.

- T. Sode, J. Kock, 2001: Traditional Raw Glass Production in Northern India: The Final Stage of an Ancient Technology. Journal of Glass Studies 43, pp. 155-169.

- M. Spaer, 1992: The Islamic Bracelets of Palestine: Preliminary Findings. Journal of Glass Studies 34, pp. 44-62.

- V. Tatton-Brown, C. Andrews, 1991: Before the Invention of Glassblowing. In: H. Tait (Ed.): Five Thousand Years of Glass . London: British Museum Press, pp. 21-61.

- K. von Folasch, D. Whitehouse, 1993: Three Islamic Molds. Journal of Glass Studies 35, pp. 149-153.

- D. Whitehouse, 2002: The Transition from Natron to Plant Ash in the Levant. Journal of Glass Studies 44, pp. 193-196.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 112

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 319

- ↑ Schick 1998, p. 75

- ↑ Whitehouse 2002, pp. 193-195

- ↑ Aldsworth et al. 2002, p. 65; Freestone 2006, p. 202

- ↑ Dussart et al. 2004; Freestone 2002; Freestone 2006; Whitehouse 2002

- ^ Whitehouse 2002, 194

- ↑ Freestone and Gorin-Rosin 1999, p. 116

- ↑ Barkoudah and Henderson 2006, pp. 297-298

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 116

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Almut von Gladiss, Jens Kröger, Elke Niewöhner: Islamic art. Hidden treasures. Exhibition of the Museum for Islamic Art, Berlin . Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin 1986, ISBN 978-3-88609-183-6 , p. 14-16 .

- ↑ Lukens 2013, p. 207

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 124

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 51

- ↑ Caiger-Smith 1985, p. 24; Pradell et al. 2008, p. 1201

- ↑ Pradell et al. 2008, p. 1204

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 51

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 291

- ↑ Tatton-Brown and Andrews 1991, p. 26

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 323; Gudenrath 2006, p. 42

- ↑ Gudenrath 2006, p. 47

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 135

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 376

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 130

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 320

- ↑ Dussart et al. 2004

- ↑ Aldsworth et al. 2002

- ↑ Freestone 2006, p. 202

- ^ Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001

- ↑ Barnes et al. 1986, p. 7

- ↑ Kröger 1995, pp. 1-6

- ↑ Kröger 1995, pp. 5.20

- ↑ Freestone 2006, p. 203; Kröger 1995, pp. 6-7

- ↑ Lukens 2013, p. 199

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 321

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 321; Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 126

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 321

- ↑ Ivanov 2003, pp. 211-212

- ↑ Redford 1994

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 131

- ↑ Spaer 1992, p 46

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 323; Israeli 2003, p. 231

- ↑ Carboni 2001, pp. 323-325

- ^ Jacoby 1993

- ↑ Gudenrath 2006, p. 47

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 371

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 136

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 137

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 374

- ↑ Carboni 2001, pp. 374-375

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 138

- ↑ Markel 1991, p. 83

- ↑ Markel 1991, p. 84

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 389; Markel 1991, p. 87

- ^ Sode and Kock 2001

- ↑ Kröger 1995, p. 184, Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001, p. 61

- ^ Carboni 2001; Israeli 2003; Kroger 1995; Pinder-Wilson 1991; Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 345

- ↑ Carboni 2001, pp. 350-351; Israeli 2003, pp. 378,382; Pinder-Wilson 1991, pp. 128-129

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 375; Israeli 2003, p. 347; Kröger 1995, p. 186; Pinder-Wilson 2001, pp. 56-60

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 303; Israeli 2003, p. 383

- ^ Carboni 1994; Spaer 1992

- ↑ Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001, pp. 119-123; Spaer 1992, p. 46

- ↑ Spaer 1992, p 54

- ↑ Israeli 2003, p. 322

- ↑ Lamm 1931

- ↑ Lamm 1928

- ↑ Pinder-Wilson 1991, p. 114

- ^ Carboni 2001; Kroger 1995; Lamb 1928; Lamm 1931; Scanlon and Pinder-Wilson 2001

- ↑ Carboni 2001, p. 139