Oriental carpet

Oriental carpets are carpets that are mainly woven and knotted in the " Orient ". The geographical area known as the “carpet belt” in which oriental carpets are made extends from Morocco through North Africa and the Middle East to Central Asia and India . By using different materials ( wool , silk and cotton ), colors and patterns, special types of carpets have developed in the respective areas, well-known examples are the Persian carpet and the Turkish carpet . The sizes and uses are also diverse: floor carpets that can fill an entire room, and Islamic prayer carpets ( sajjadah ), as well as oriental carpets as pillows, carrying and saddlebags, decorative blankets for animals or decorative ribbons for tents. Knotted Jewish Torah wraps ( parochets ) and Christian oriental carpets with sacred motifs are also known.

It is not clear whether carpet weaving was first developed in permanent settlements or by nomads who needed protection from the cold of the ground. The technique of making carpets could have spread with nomadic migrations. Central Asia is often assumed to be the region of origin; According to a hypothesis by Volkmar Gantzhorn, the oriental carpet was created in the Armenian highlands . The cultural confrontation with the Eastern Roman Empire , the Islamic expansion , invasions by foreign peoples such as the Mongols and wars between the Ottoman Empire and the Persian Empire have profoundly influenced the handicrafts of carpet knotting in the core areas of the “carpet belt”. With the advent of Islam , the knotted carpet developed under the influence of Islamic art into the textile known as the “oriental carpet” or “Islamic carpet”.

The art of carpet knotting is one of the oldest cultural achievements of mankind. The "traditional art of carpet weaving" in Fars , Kashan and Azerbaijan was in 2010 in the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Representative List of UNESCO added. To this day, oriental carpets are mostly made by hand.

history

Ancient written sources from the 2nd millennium BC Chr.

Probably the oldest sources mentioning carpets are cuneiform scripts on clay tablets from the royal archives of Mari from the second millennium BC. The Akkadian word for carpet is "mardatu". Specialized carpet weavers, "kāşiru", are linguistically differentiated from other special professions such as bag makers ("sabsu" or "sabsinnu").

“Speak to my Lord! Your servant Ašqudum (says), I asked my master for a rug, but I was not given one. (Plate 16 8)

Speak to my Lord! Your servant Ašqudum (says), Because of the woman who is all alone in the palace of Hişamta - The matter is unworthy. It would be good if five women who weave carpets were with her. (Plate 26 58) "

Palace inventories from the Nuzi archives from the 15th and 14th centuries BC BC record 20 large and 20 small mardatu to cover the chairs in the palace of Idrimi in Alalach .

The ancient Greeks used carpets. Homer writes in Iliad 17, 350 that the body of Patroclus is covered with a "splendid carpet". In the Odyssey , books 7 and 10, “carpets” are also mentioned. Persian carpets are first used around 400 BC. Mentioned by the Greek author Xenophon in his work Anabasis :

"Αὖθις δὲ Τιμασίωνι τῷ Δαρδανεῖ προσελθών, ἐπεὶ ἤκουσεν αὐτῷ εἶναι καὶ ἐκπώματα καὶ τάπιδας βαρβ .αρις. […] Καὶ Τιμασίων προπίνων ἐδωρήσατο φιάλην τε ἀργυρᾶν καὶ τάπιδα ἀξίαν δέκα μνῶν. "

“Then he went to Timasion the Dardanian, because he had heard that he had some Persian drinking vessels and carpets. [...] Timasion also drank to his health and gave him a silver goblet and a carpet that was worth 10 mines. "

Xenophon describes Persian (literally: "barbaric", non-Greek) carpets as precious and worth a diplomatic gift. It is not known whether these carpets were knotted or made using some other technique, such as flat weave or embroidery .

Pliny wrote in his Naturalis historia 8:48 that carpets ("polymita") were invented in Alexandria. It is unknown whether these carpets were flat woven or pile carpets, as the texts do not give detailed information. However, it is clear from the texts that carpets were of great value to the owners and confirmed their high rank.

Theories on the origin of the knotted carpet

The few remaining carpet fragments known to us are not the oldest, only the oldest surviving carpets. Due to the lack of evidence and other records, the question of the origin of the knotted carpet depends on hypotheses.

The oldest surviving carpet fragments were found in widely separated places. Their dating extends over a long period of time. The oldest according to current knowledge rug found the Russian researcher Sergei Rudenko and M. Grjasnow in 1947 in a Scythian royal grave in Pazyryks-Hochtrockental in the Altai Mountains , Siberia . Rudenko assumed that the carpet was in the 5th century BC. BC, at the time of the Achaemenids , most likely not in a nomadic environment.

The Pasyryk carpet is tied in symmetrical knots, the fragments from East Turkestan and Lop Nor have alternating knots tied around only one warp thread, the fragments from At-Tar are tied with symmetrical, asymmetrical and asymmetrical knots tied in a loop technique, while the Show fragments of Fustāt loop fabric, single or asymmetrically tied knots. The different types of knots in the earliest known carpets, found in places far apart, suggest that the knotting technique as such evolved in different places.

Erdmann's theory of nomadic pastoral origin

Kurt Erdmann assumed that the first carpets with knotted pile were knotted by nomad shepherds, who used them instead of animal skins to protect the floor of their tents from the cold. He supports his hypothesis by observing that knotted carpets are only produced in certain geographical areas (between the 30th and 45th parallel), where the climate demands protection against the cold on the one hand, and where steppe vegetation prevails, which makes it possible to keep herd cattle but not to hunt animal skins in sufficient quantities. After the discovery that decorative patterns can be created by knotting in differently colored yarns, the originally long carpet pile, which was originally long for the function, was sheared off shorter and shorter so that the pattern emerged more clearly.

Chlopin's theory of the sedentary weavers

In the Bronze Age women's graves of a permanent settlement in southwestern Turkestan, Igor N. Chlopin unearthed a number of knives remarkably similar to those used by Turkmen knotters to shear the pile of their carpets. Chlopin put forward the thesis that knotted carpets were made in permanent settlements as early as the Bronze Age. Some very ancient motifs in Turkmen carpets are very similar to the ornaments on ancient pottery from the same region. These findings suggest that Turkestan might be one of the first regions where carpets were knotted, but not necessarily the only one. This theory is supported by the fact that the oldest surviving knotted carpet, the Pasyryk carpet, already in a very fine weave with carefully and detailed pattern drawing, was certainly not a product of the nomad tent, even taking into account the circumstances and accompanying finds. This does not refute the theory of nomadic pastoral origin. It can be assumed that the origins of carpet weaving go back much further into the past.

state of research

In the light of ancient written sources and archaeological discoveries, it is very likely that the technique of carpet weaving developed from an older weaving technique and was first used in permanent settlements. Technology may have evolved at different times and in different places. During migrations of nomadic or displaced sedentary groups, perhaps from Central Asia, technology and patterns have spread in the area known as the “carpet belt”.

The origin of the weaving and knotting technique can be found with some certainty in the manufacture of flat woven fabrics ( Kelim ) in Central and Central Asia. The nomads made essential accessories such as sacks, bags, blankets, flat woven fabrics, carpets and wall hangings for their tents for their daily life . Braiding is seen as the preliminary stage of weaving. In principle, producing a fabric means nothing more than tightly interweaving warp and weft threads and condensing the fabric. This creates a dense, flat fabric without pile, similar to a very coarse fabric. Flat woven fabrics have always been part of nomadic and rural everyday life.

Thicker, heavier textiles are created by introducing additional, loose weft threads or weft threads woven in loops using the “winding technique”. The winding technique with additional weft threads produces either flat Soumak fabrics , if the additional threads are woven in tightly, or the loop fabric . In loop weaving, the weft threads are looped around a guide rod so that rows of loops are created on the side of the carpet facing the weaver. When a number of loops are completed, either the rod is simply pulled out so that the loops remain closed. The finished fabric is then reminiscent of a very coarse terry cloth . Another possibility arises from the fact that the loops can still be cut on the guide rod. This creates a fabric that looks like a real knotted carpet. In contrast, real knotted carpets are made in such a way that individual pieces of yarn are knotted into the warp threads, the thread being cut after each knot and the fabric being fastened with weft threads after each row of knots. It seems very likely that knotted carpets were made by people who already had experience with loop weaving.

Fragments from Turkestan, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan

Carpet fragments from the 4th or 3rd century BC Were excavated in the burial mounds of Bashadar in the area of Ongudai , Altai region , Russia by Sergei I. Rudenko, the discoverer of the Pazyryk carpet. They are characterized by a fine knot with 4650 asymmetrical knots per square centimeter.

The explorer Aurel Stein found flat-woven kilims in Turpan , in the administrative region of Hotan , East Turkestan, China, which can be dated back to the 4th or 5th century AD. Carpets are still being knotted in this area. Carpet fragments were found in the Lop Nor area . These are tied with symmetrical knots. After each row of knots, five to seven weft threads in different colors were woven in to create a striped pattern. These fragments are kept in London's Victoria and Albert Museum .

Other fragments, both with symmetrical and asymmetrical knots, have been found in Dura Europos in Syria , as well as in the caves of At-Tar in Iraq . The latter were dated to the first centuries after Christ.

These findings, which are very rare overall, show that Western Asia had all the skills and knowledge required for dyeing wool and knotting carpets as early as the first century AD.

Fragments of knotted carpets from not exactly known sites in northeast Afghanistan , probably from the province of Samangan , were dated by means of the radiocarbon method to a period between the 2nd century AD and the early Sassanid period. Some of these fragments show animals such as deer, which are sometimes arranged in a procession and are thus reminiscent of the Pazyryk carpet, or a winged mythical creature. The warp and weft threads as well as the pile are made of wool spun into coarse yarn. The fragments are tied with asymmetrical knots. After every third to fifth row of knots, strands of unspun wool or strips of fabric and leather are incorporated. These fragments are in the Al-Sabah Collection in the House of Islamic Art ( Dar al-Athar al-Islamyya ) in Kuwait .

Anatolian carpets from the Seljuk period from the 13th to 14th centuries. century

The oldest largely preserved knotted carpets were found in the Anatolian cities of Konya and Beyşehir as well as in Fustāt in Egypt and dated to the 13th century. They come from the time of the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks . No carpets from this early period have survived from other countries.

In the early 14th century, Marco Polo wrote in his travelogue:

"... et ibi fiunt soriani et tapeti pulchriores de mundo et pulchrioris coloris."

"... and here they make the most beautiful silk fabrics and carpets in the world, and in the most beautiful colors."

Coming from Persia, Polo traveled from Sivas to Kayseri . Abu'l-Fida quotes Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi , who reported on carpet exports from Anatolian cities in the late 13th century: "This is where Turkoman carpets are made, which are traded in all other countries". He, like the Moroccan merchant and traveler Ibn Battūta, name Aksaray as a major center of carpet weaving in the early to mid-14th century.

Eight carpet fragments were found in 1905 by Fredrik Robert Martin in the Alâeddin mosque in Konya, four more were found by Rudolf Meyer Riefstahl in 1925 in the Eşrefoğlu mosque in Beyşehir, also in Konya province. More fragments appeared in Fustāt, Egypt .

Due to their original size (Riefstahl published a carpet that is 6 m long), the Konya carpets can only have been made in a specialized city manufactory, because looms of this size do not find a place in a village house or a nomad tent. It is not known exactly where these carpets were once knotted. The field patterns of Konya carpets are mostly geometric and rather small in relation to the size of the carpet. The very similar patterns are arranged in diagonal rows: hexagons with straight or hooked outlines; Squares with stars in them and ornaments in between, similar to Kufic script ; Hexagons or stylized flowers and leaves in diamond ornaments. The main border often contains Kufic ornaments. The corners are not "dissolved", which means that the pattern of the border appears cut off at the corners and does not continue around the corner. The colors (blue, red, green, less often white, brown, yellow) appear subdued. Often two different shades of the same color are right next to each other. No two patterns are alike on these carpets.

The carpets from Beyşehir are very similar to those from Konya in terms of pattern and color. In contrast to the animal carpets of the following period, images of animals are rarely seen on the Seljuk carpets. On some fragments there are horned quadrupeds facing each other, or birds on either side of a tree.

The style of the Seljuk carpets shows parallels to architectural decorative elements of contemporary buildings such as the mosque in Divriği or buildings in Sivas and Erzurum and could be related to ornaments of Byzantine art. The carpets are kept in the Mevlana Museum in Konya and in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul .

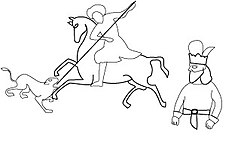

Early Anatolian animal carpets from the 14th-16th centuries century

Carpets with special animal patterns were made in Anatolia according to today's knowledge . The stylized representations of animals tied into the pile are characteristic of this group. They were made in the 14th to 16th centuries during the Seljuk and early Ottoman times and were also exported to Western Europe. Very few of these carpets have survived, most of them in fragmentary condition. However, animal carpets were often depicted in paintings from the early Renaissance period . The time when the carpets were made can be determined by comparing them with their painted counterparts. Their investigation has contributed significantly to the development of the chronology of Islamic art. Until the Pasyryk carpet and other fragments were discovered, the “phoenix and dragon” carpet kept in the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin was considered the oldest in the world. Further finds of carpets of this type, for example the animal carpet found in Marby, Sweden, document an export of Anatolian carpets to Northern Europe.

The Pazyryk carpet , around 400 BC. BC ( Hermitage , Saint Petersburg)

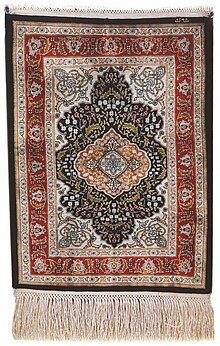

Carpet fragment from the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir , Anatolia, Seljuk period, 13th century

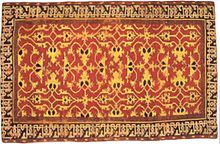

Seljuk carpet, 320 × 240 cm, from the Alaaddin Mosque in Konya , 13th century

Animal carpet , Anatolia, 11. – 13. Century ( Museum of Islamic Art , Doha)

"Phoenix and Dragon" carpet, 164 × 91 cm, Anatolia, approx. 1500 ( Museum of Islamic Art , Berlin)

Another story

In the Middle Ages, some carpets came to Europe through the Crusaders , and later carpets from the Orient were brought to Europe by travelers and business people as gifts, in large numbers through trade, to Rome or Venice . From this time on, more carpets have been preserved and allow a more detailed overview of the history of carpet weaving in individual countries.

Manufacture and construction

loom

There are two types of looms distinction

- the lying or horizontal and

- the standing or vertical loom.

Horizontal loom

The nomads use the horizontal loom. The very simple device consists of four pegs in the ground and two crossbeams for tensioning the warp threads. This preserves nomadic flexibility. If the cattle are moved on, the pegs are pulled out of the ground and folded together with the semi-finished product and set up again at the new location. The size of the carpet is limited by the dimensions of the loom set up. This technique is still practiced among the traditionally living nomadic tribes. On the other hand, many nomads have settled down so that their carpets are made at home. They then often use fixed horizontal looms on which several people can work next to each other at the same time.

- Afshars , Bakhtiars , Baluches , Kashgai , Kurds , Lurs and Turkmens in Persia,

- Baluch and Turkmen in Afghanistan

- Kurds and mountain nomads ( Yörük ) in Anatolia.

Vertical loom

In contrast to the horizontal loom, the standing or vertical loom enables other working methods, as well as larger carpet formats. The simplest chair has solid transverse trees and the length of the loom determines the length of the carpet. In the factories the cotton warp threads are stretched on beams or in larger factories in the roller loom on metal rollers. Depending on the width, several can work on the loom at the same time. The rollers with the warp threads are rotated further and the finished carpet part is turned down or back. This means that the working height of those sitting in front of the weaving chair is maintained.

A distinction is made between three types of upright looms, which can be technically modified in various ways. There is the fixed village loom, the Tabriz or Bunyan loom and the scroll bar loom.

- The fixed village loom is mainly used in rural areas of Iran and Turkey and consists of a fixed upper and a movable lower beam ("fabric beam"), which is fastened in slots in the side beams. The correct tension of the warp threads is created by wedges that are driven into the slots in the side bars. Work is carried out on a height-adjustable plank, which is placed higher and higher as the carpet progresses. A carpet produced on such a loom can be as long as the loom is high.

- The Tabriz loom, named after the city of the same name, is traditionally used in northwestern Iran. The warp threads continue behind the loom like a vertical conveyor belt. The tension of the warp threads is adjusted and maintained with wedges. When a section of the carpet is finished the warp threads are loosened and the section is pulled down onto the back of the loom. The working height does not change. This process repeats itself until the carpet is finished. For technical reasons, a carpet can be knotted on a Tabriz loom that is a maximum of twice as long as the height of the loom.

- The scroll bar loom is widely used in all countries that manufacture carpets. It consists of two movable bars around which the warp threads are wrapped. The beams are attached with notches. When a section of carpet is ready it is wound onto the lower beam. In theory, a carpet of any length can be made on a scroll bar loom. In some, especially in Turkish, manufacturers, several carpets are knotted one behind the other on the same warp threads and then cut apart at the end.

The closer the warp threads are, the denser the carpet will be. The width is determined by the crossbar. The length of the carpet is determined from the total distance between the crossbars. The knotting process begins at the bottom of the warp threads.

material

The warp and weft form the base fabric and the pile the pattern. Various material combinations are used for this.

| Chain | shot | Pile |

|---|---|---|

| Sheep wool | Sheep wool | Sheep wool |

| cotton | cotton | cotton |

| Natural silk | Natural silk | Natural silk |

| cotton | cotton | Natural silk |

| cotton | cotton | Rayon |

| cotton | cotton | Sheep wool |

Fibers made from wool, cotton and silk must be twisted or spun. The thread can be spun as a counterclockwise S twist or a Z clockwise twist. When determining the age and origin of a carpet, an appropriate analysis of the yarn can be very helpful.

Wool

Three types of sheep breeds are important for carpet production: the Merino sheep , the Crossbred sheep (cross breeding) and the Cheviot sheep .

Differences in quality and appearance result from the breed of sheep and the climatic conditions under which the animals live. Because of their climate and vegetation, highland sheep give better wool than sheep from mild climates. The age of the animals also influences the quality. At a young age, the "wooliness" is better, it only receives sufficient resistance after the animal is one year old. The shearing is usually done in spring.

Wool is differentiated according to when and how often it is sheared. Yearling wool comes from the first or second shear after ten to twelve months. Lambswool is the wool of the first shear after six months, the Kurkwolle (pers. = Fluff, soft wool). Single wool is shorn only once a year, double wool from sheep that are sheared twice a year. Hide or slaughter wool is wool from slaughtered sheep, and death wool from dead sheep.

The fleece parts are still raw and naturally soiled , they are gently washed and degreased in several vats connected in series in water with the addition of weak alkalis. The mechanical load must remain low in order to avoid matting . Synthetic detergents that degrease more easily are being used increasingly . Two kilograms of washed wool are obtained from a merino sheep. Before spinning, the fibers are opened and combed. The wool can be plucked with the hands without any tools. Hand cards are two small boards with handles that have many small, angled steel hooks on the inside, so that they can be loosened faster and more evenly. Carding machines are available for this in the modern spinning mill .

Since the beginning of the industrial revolution , wool has been spun by machine . Previously, all of the raw wool used to make carpets was spun by hand by spinners; this is characterized by a kind of grain, an irregular thickness of the individual threads. Especially carpets with little or no pattern get their character like the gabbeh .

silk

Natural silk is obtained from the cocoons of the mulberry moth. The origin of this insect is China, breeding came via Korea to Byzantium and southern and central Europe and was processed into fabrics here in Italy and then in France. Ten days after egg-laying, caterpillars hatch and only eat fresh leaves of the mulberry tree. After four weeks they are as thick as a finger and pupate. Before the spinners hatch, the larvae in the cocoons are killed by hot water or steam. The outer layers loosen. Now the reel silk is "unwound" from the cocoons, that is, unwound and wound up. A cocoon can yield up to 25,000 meters of thread.

Isfahan carpets from Persia and Hereke carpets from Turkey use this reel silk for warp threads. Some types of carpet are made entirely from silk. Silk is not as elastic as sheep's wool, but it is very hard-wearing. Due to its high tensile strength, silk can be spun thinner and carpets of very fine fineness with a high knot density can be knotted.

cotton

After wool, cotton is the material used in carpet manufacture. The cotton plant is a shrub to tree-like plant that is grown anew every year. The ripe fruit capsule bursts and the fibers of the cotton swell out. These fiber balls are collected by hand or by machine and ginned. Egrening is the separation of the seed hairs from the seeds. Cotton threads are very strong and robust and have established themselves as carriers for the knots in the base fabric in the weft and warp. They are unsuitable for the pile . Mercerized cotton is used in the production of knotted carpets . A bath in cold caustic soda gives the cotton a silky shine. The process was developed by John Mercer in 1844 . A mixed yarn made of mercerized cotton with a small amount of silk is called a flosch in the carpet trade.

Occasionally cotton is used as an effect thread in the pile (loop) or for knotting particularly bright white ornaments, unbleached animal wool always has a yellowish-white color. However, as a pile yarn, cotton easily absorbs dirt and the pile strength is low, the pile collapses quickly. Pure cotton carpets are used as summer carpets. Summer carpets are flat woven fabrics that are laid out during the summer months and on special occasions; knotted carpets were placed over them during the cold season. Summer carpets were also made in Anatolia, in the Panderma region. In India they are called dhurries .

Colors and coloring

Natural colors

The art of dyeing developed with the art of knotting, it goes back to millennia-old traditional methods. Wool and silk for carpet production are preferably dyed with natural dyes. The colors that can be achieved are not garish and screaming, but rather blend into delicate and harmonious combinations. A common coloring agent for red and maroon is obtained from the roots of the madder plant . The dyes alizarin and purpurine are of particular importance here. Different shades of color were achieved by staining with aluminum salts (red) or iron salts (violet to brown). Purple red - "the color of kings" - comes from the tanks of scale insects ( cochineal , Kermes scale insect and Kermesläusen ), which essentially Carmine contain and dyers paint ( laccaic ). For blue is the root of the indigo plant , for yellow dyer's rocket , turmeric , turmeric , camomile or the dye of the pomegranate shells used. Green tones can be created by over-coloring indigo with a yellow dye. With indigo and madder, violet and brown-violet tones are colored. Saffron provides a yellow-orange hue. Cochineal and logwood ( logwood ) from America reached the Orient in the 16th century. Small strands of yarn for the pile are dyed by hand. Each dyed lot of wool is knotted into the carpet by hand. In the next batch of dyed wool, a color deviation is inevitable - this is called abrash . The color change is shown in the horizontal direction, i.e. in the working direction.

It is not possible to determine with certainty whether the colors in a carpet come from natural dyes. Often this can only be determined with the help of chemical tests. Two of the most important natural colors - indigo blue and madder red - can be precisely imitated chemically.

Madder madder (Rubia tinctorum)

Indigo, collection of historical dyes, Technical University of Dresden

Synthetic colorants

As a semi-synthetic dye, indigo sulfonic acid, made from indigo and sulfuric acid , was used in some carpets from the middle of the 19th century . Aniline paints made from coal tar were mainly produced in Europe by German paint factories since the middle of the 19th century and soon reached the Orient on various trade routes. Because of the low price and the brighter colors, they spread and replaced or partially supplemented the natural dyes. This makes it easy to date carpets from between 1860 and 1870. In particular, triphenylmethane dyes and azo dyes have been used. Dyes used for dyeing were, for example, mauvein , aniline blue , fuchsine , congo red , crystal violet , malachite green , methyl orange , naphthol yellow , Ponceau 2R , fast red A (Roccelline) and amaranth . Picric acid could be detected in a Kurdish carpet . However, the first synthetic dyes were still impure, faded quickly and the virgin wool felted easily during the dyeing process, so that the demand for these products fell again. In Persia, they were banned in 1900 on the orders of the Shah . Nevertheless, modern dyes with improved fastness and color strengths and the consistently lower price are used for fiber dyeing.

The knots

The "Turkish" Gördesknot is a symmetrical double knot that is mainly used in the Anatolian art of knotting. The Anatolian carpet requires more knotting time due to the Gördes knot and requires more of the valuable wool. In a symmetrical or Turkish knot, the two ends of a knot thread look up between the corresponding two warp threads and form the pile.

The "Persian" Senneh knot is characteristic of Persian carpets as an asymmetrical single knot . The term is actually misleading because in the Persian city of Senneh (today Sanandadsch ) the symmetrical "Turkish" knot was traditionally used. In an asymmetrical or Persian knot, only one end of a knot thread looks up between the two corresponding warp threads, while the other end of the knot thread is led up next to both warp threads. The free end of the thread can peek out on both the right and left side of the warp thread, which is called "opening to the right" or "opening to the left". This is important because certain regions or tribes each use specific nodes. It is easy to find out in which direction asymmetrical knots open by determining the side line of the carpet by hand.

There is no geographical assignment of these two node types. Both are used (almost) everywhere.

A type of knot is called a type of knot, which mostly comprises four warp threads instead of two to save money . Dschufti knots can be tied symmetrically or asymmetrically opening to the left or right. Since the beginning of the 20th century, it has been used primarily in carpets manufactured for the trade in order to save time and material, especially in larger, single-colored areas of the carpet field. The Dschuftikonten results in a poorer quality, because compared to the traditional knotting only half the amount of the knotting yarn is used. The carpet pile is then not as dense and wears out faster.

Another variant, the single knot , occurs in old Spanish and Coptic knotted carpets. The single knot is tied around a single warp thread. This technique is very old and some of the fragments found by Aurel Stein in Turpan are tied with single knots.

There are also uneven knots that, for example, leave out a warp thread, are knotted over three or four warp threads, individual individual knots, or two knots that share a warp thread asymmetrically to the left or right. They are often found in Turkmen carpets, where they contribute to the particularly dense and regular structure of these carpets.

The staggered or offset knotting shows knots that alternately split pairs of warp threads in successive rows. This technique allows the color to change from half a knot to the next and thus allows diagonals to be tied at different angles. Such a weave can sometimes be found in Kurdish or Turkmen carpets, especially those of the Yomuds. Usually the individual knots are tied symmetrically.

The upright pile of oriental carpets usually slopes towards the lower end of the carpet, because every single knot thread is pulled down and cut off after it has been knotted. If you run your hand over the pile, a knotted carpet offers a "line" like animal fur. By determining the line, you can see at which end the knotting started. Prayer rugs are often started from the side of the arch tip, that is, "standing upside down". There are probably technical reasons for this (you can focus on the more complicated arched pattern at first and adjust the field later), but mostly practical because the pile later tilts towards you, which is more pleasant to the touch.

The knot density

The fineness of oriental carpets is defined by the number of knots per area:

| rating | Number of nodes / m² |

|---|---|

| very roughly knotted | 15,000-90,000 |

| roughly knotted | 90,000 - 200,000 |

| medium fine knotted | 200,000 - 500,000 |

| finely knotted | 500,000-910,000 |

| very finely knotted | 910,000 - 1,200,000 |

| rarely finely knotted | over 1,200,000 |

The approximate number of knots per square meter is determined by counting on the back of the carpet with the help of a ruler. The number of nodes, visible as small "bumps", is determined to be 10 mm horizontally and then 10 mm vertically and the result is multiplied for the area. The number of nodes per square centimeter multiplied by a factor of 10,000 results in the number of nodes per square meter. With five knots on 10 mm horizontally and six knots on 10 mm vertically the result is 5 × 6 = 30 knots per square centimeter and thus 30 x 10,000 = 300,000 knots per square meter.

With a knot density of 10 × 10 knots (= 100 per cm 2 ) it takes about a year to knot one square meter of oriental carpet. With a number of knots of 15 × 15 knots (= 225 per cm 2 ), three to five years have to be calculated per square meter. At 24 × 24 knots (= 576 per cm 2 ) it is a world-class carpet made of silk, which took about eleven years to produce.

Conversion from Radj to knots

The knot density of Tabriz carpets is given in Radj . The Persian data for knot densities are calculated in knots on the chain per radj. The length of one Radj corresponds to about 7 centimeters, i.e. 0.07 meters. One meter corresponds to 14.29 Radj and the knots per linear meter of chain are calculated from Radj x 14.29. A carpet with 22 knots per wheel therefore has 310 knots per linear meter of chain, because 22 × 14.29 = 314.

To convert to the usual number of knots per square meter , Radj x Radj x 14.29 × 14.29 = Radj x Radj x 204. For example, the specification “22-Radj carpet” corresponds to a knot density of 100,000 knots per square meter. Calculation: 22 × 22 × 204 = 98,736, so almost 100,000.

The knotting

A piece of kilim always has to be woven at the beginning. The wefts are entered and pegged in order to give the first row of knots of the knotted carpet a hold. To tie a knot, choose a thread of the appropriate color. A piece of thread is cut with a knotting knife ("Tich") from the ball hanging above the knotter. The thread is looped around two adjacent warp threads so that the right end of the thread protrudes. The loop is pulled tightly downwards and cut off at the level of the right end of the thread as it is pulled down. This is the procedure for each pair of chains. A special knife is used in some regions for the Gördesknoten. The tip of this "Tabriz knot hook" is provided with a hook so that the right warp thread can be gripped and the right half of the knot can be pulled.

After the first row of knots has been completed, two or more wefts are drawn in, that is, the weft threads are fed alternately through the warp threads. If the weft threads are not carried over the entire width of the carpet, so-called " loafers " arise . Then knots and wefts are compacted by blows with a wooden or metal comb and the next row of knots follows. This is how the carpet gains its length, row by row, from bottom to top. The entirety of the knotted knots of different colors forms the pile with the desired pattern. The upper end of the finished knot is again - as at the beginning - a few rows of tightly woven weft threads in kilim style. A corresponding securing thread is inserted as a substitute. Both variants have the task of preventing the edge knots from becoming detached from the tissue. The side ends form the edge attachment on the long sides of the carpets. They are created by wrapping the edges with the appropriate material. The warp threads running through are visible on the finished piece as fringes on the narrow sides.

The shearing

After knotting, the pile must be brought to a uniform height. The shear will lower the pile and make the pattern clearer. Fine, detailed knots require a low pile, carpets with a coarser knot can have a longer pile. Shearing used to be done with special knife blades or large, flat scissors. Today carpets are sheared with machines that look similar to grinding machines and vacuum the cut fibers straight away. A relief effect can be created by shearing or cutting the pile along the color gradients.

The laundry

A carpet with poorly washed wool is always heavier, more sensitive to dirt and more susceptible to moths. Woolen laundry is one of the most important processing factors in the manufacture. It is a multi-stage process, such as pre-wash, main wash and various rinses. This removes loose fibers, rinses out excess paint and creates a shine, the pile is organized and smoothed and the pattern emerges more clearly. Previously, the finished piece was simply immersed in the running water of a stream and hung in the sun to dry. A good wash can produce many effects that will come about by themselves over time - it can keep the red glowing or it can mute it to shades of pink, rust, copper, brown, gold or beige. Chandelier (Florglanz) is often achieved by a chlorine or gloss laundry. In the knotting shops, after washing, the carpet is stretched, dried and pounded soft.

Pattern and style

Oriental rugs are known for the rich variety of their colors and patterns and share traditional features that have not changed for centuries. Most carpets are rectangular, occasionally square, round and hexagonal shapes. Within this rectangular shape, almost all of the patterns are divided into a central field and a border. The border, or the frame, is usually composed of strips of different widths.

With the exception of a relief effect created by uneven shearing of the pile, a carpet pattern is always created by the two-dimensional arrangement of different colored knots. Each tied node can be viewed as an image point or pixel of an image made up of multiple rows of nodes. The more skilled the knot (or, in the case of manufactured carpets, the designer), the finer the pattern is.

The formal design of the inner field can be made according to the following basic patterns:

The patterns of the midfield

- Medallion pattern

- The main motif is in the middle of the field or several small medallions are arranged one behind the other on a longitudinal axis. Corner quarters, which usually correspond to a quarter of the main motif, are located in the corners of the field. If the middle field is empty, with or without a medallion, we speak of mirror carpets.

- Field sampling

- The background is divided into several rectangular or square fields, diamonds or diagonal strips.

- Repeat pattern

- This pattern is created through multiple repetitions of the same motifs or motif combinations in the interior of the carpet (all-over).

- Picture carpet

- The entire fund is designed in the form of pictorial representations (garden, hunting, plant, animal, vase carpet).

- Prayer rug

- The characteristic of these carpets is the representation of the prayer niche ( mihrāb ) in the inner field.

Subdivision according to patterns

The samples can be roughly divided into three categories:

- the rectilinear or geometric style

- the curvilinear or floral style

- the figural style related to people and animals

- Pattern types

- Examples

"Serapi" carpet, Heris area : predominantly rectilinear ("geometric")

The geometric style uses the straight line with horizontal, vertical and diagonal sections and forms its various patterns from it. In Anatolia, the geometric style dominated, which was strongly developed under the Seljuk dynasty from the 11th to the 13th centuries until the end of the 15th century. The pattern extends over the entire midfield. Geometric patterns such as octagonal stars, hooked octagons and squares can be found in the entire subsequent carpet art of the Near East.

The floral style, on the other hand, uses the curved line. That is why we speak of the curvilinear style. The Persian artists of the Safavid period were Shiites and figurative representations were permitted provided that they were used in a spiritual or contemplative context. Their task was to give an idea of paradise or to present moral concepts through epic or mythical scenes. The Indian Mughals oriented themselves strongly to the Persian courts.

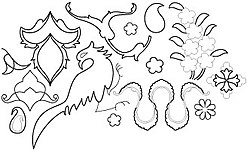

Arabesque - Eslimi - Rumi

The pattern called Eslimi or Islimi in Persia is common in Europe as " Arabesque Dessin". The Turkish name for this ornament was Rumi . The arabesque was a leaf tendril that consisted of two elements, a split leaf volute that was repeated, and a connecting tendril. The tendrils were extremely versatile in their appearance, their mostly spirally curved individual forms could be intertwined and intertwined in a wide variety of ways. It is probably the most oriental of all patterns and originally comes from the high art of faience work cultivated in the Orient early on. The domes of mosques and other buildings are often covered with ornate tiles that defy wind and weather thanks to their glazing. After this exemplary play of colors and patterns, the corresponding carpet pattern is knotted with flowers, plants, twigs and tendrils. Paired with stylized leaves, fork tendrils and cloud band ornaments, this overall pattern becomes an Eslimi pattern.

Garden representations

|

|

|

|

Left picture : al-Jami, miniature, early 16th century.

Right picture : “Bellini Carpet” , Anatolia, late 15th – early 16th century. |

||

An essential element of Islamic architecture is the design of gardens and equating them with the “garden of paradise”. In the classic Persian-Islamic form of " Tschahār Bāgh " there is a rectangular, watered and planted square, intersected by elevated paths that usually divide the square into four equal sections.

The idea of equating a garden with paradise stems from the Persian culture. From the Achaemenid Empire narrated Xenophon the description of "Paradeisoi" pleasure gardens, who established the Persian ruler throughout their empire in his dialogue "Oeconomicos". The earliest reconstructable Persian gardens were excavated in the ruins of the city of Pasargadae . The design of the palace gardens of the Sassanids in Persia had such an effect that the old Persian term for garden Paradaidha as " paradise " was borrowed in many European languages as well as in Hebrew, where the term Pardes is still used today. The shape of the Persian garden found widespread use in the Islamic world.

The classic garden design can also be found on the carpets as "woven gardens".

Motif and pattern development

In a traditional handicraft such as carpet knotting, which has been practiced for centuries, motifs and patterns are not fixed, but are subject to constant changes, practically with each new piece. Some of these changes are more passive and based on human creativity or the trial and error of individual weavers. Such deviations are not foreseeable and tend to be random. The active adaptation of adopted motifs to an independent artistic tradition often takes place in a creative process known as stylization .

Basic rules of motive development

As they are passed on from generation to generation within the same village or tribe, given patterns change over time. Changes also take place when a pattern “wanders”, i.e. is adopted and adapted by a tribe, village or factory. Peter Stone identified five basic rules for developing motifs:

- Motives develop from the complicated to the simple.

- Motifs that were originally rectilinear change less than originally curvilinear patterns.

- Individual elements from composite (complex) patterns are taken out of context and used in other combinations of elements or motifs.

- Borrowed motifs and patterns are adapted to the traditional style of the weavers who have adopted them and combined with the existing pattern repertoire.

- Motifs migrate from the cities to the villages and tribes, rarely the other way around.

stylization

Stylization is an active process and describes the appropriation of foreign motifs and their integration into one's own stock of patterns, for example the adoption of patterns from the court and city manufactories in village or nomad carpets. This process is very well documented for Ottoman prayer rug designs. Stylization describes a series of small, step-by-step changes both in the overall design and in the details of smaller patterns and ornaments over time. As a result, a pattern can change so much and move away from the original model that it is hardly recognizable. In the art-historical tradition of the “Viennese School” around Alois Riegl , the process of stylization was seen more as the “degeneration” of a pattern. Today stylization is seen more as a real, creative process within an independent artistic tradition.

Rules can also be derived for stylization. Motives develop:

- from animal forms (animal) to vegetable (floral) forms;

- from naturalistic to “ impressionistic ” to abstract forms;

- from curvilinear to rectilinear design;

- from asymmetrical to symmetrical shapes.

The analysis of the motifs and patterns of oriental carpets makes it possible to assign them to a uniform group and to bring seemingly very different motifs into a meaningful context. Provided that sufficient numbers of specimens are preserved, motifs can be assigned to an artistic or tribal tradition and their changes over time can be traced. In some cases, for example when motifs and patterns from Chinese, Caucasian or Turkmen traditions are found in Western Anatolia, the patterns reflect the history of the tribes and their migrations.

- Stylization using the example of the Anatolian prayer rug

Ottoman prayer rug from the court manufactory, Bursa, late 16th century (James Ballard Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art )

Imagery and symbolism of the oriental carpet

Oriental carpets of different origins often have common motifs. In many cases, attempts have been made to trace the possible origins and meaning of the ornaments by understanding them as symbols . Linked motifs in folk art are subject to passive processes of change over time, as they are subject to human creativity, trial and error, unpredictable deviations, and the more active process of stylization . The latter process is well documented, as the inclusion of artistic designs and patterns from the city workshops in the work of rural villagers and nomads can be traced on the basis of preserved carpets. It follows from this that the products of traditional village or nomad weavers are more likely to be considered for the analysis of the imagery and symbolism of the carpet pattern than the artistic and artificial pattern designs of workshop production.

The knowledge of the original meaning of the patterns and ornaments has largely been lost in the countries of origin due to the break with the established tradition. Western viewers are primarily interested in “recognizable” elements, for ornaments that “could represent” something. It is therefore debated whether the search for the meaning of symbols follows a view that has been biased by Western visual arts, according to which a pattern, realistic or abstract, is to be understood as a representation with real or symbolic content. Coupled with the lack of surviving village and nomadic carpets from older times that could serve as evidence for scientific analysis, this often leads to speculation about the origins and "meanings" of patterns, and sometimes unproven claims.

The cultural historian May H. Beattie (1908–1997) wrote in 1976:

“The symbolism of oriental carpet patterns has recently been the subject of many articles. Many of the ideas published are of great interest. It would not be wise, however, to discuss such a topic without a deep knowledge of Eastern philosophy, for it offers much unreliable material for unbridled fantasies. Certain things can be easily believed, but sometimes it is not possible to prove them, especially in the religious field. Such ideas deserve careful attention. "

Two basic elements of the imagery of the oriental carpet are symmetry and the self-completion of patterns.

symmetry

Symmetry is a fundamental tool used by the human mind to process information. From a wide range of possible symmetries, each cultural group selects a number with the help of which it deals with information and preserves it. In the pattern formation of oriental carpets, mirror symmetry is important, both in the composition of the entire carpet surface as well as in the composition of a single ornament. Simple geometric elements such as the square have mirror symmetry in both the horizontal and vertical axes. The isosceles triangle, in mirror or rotational symmetry, or the cross, are simple shapes that satisfy the laws of symmetry. More complex motifs, such as the Elibelinde or the arch or (prayer) niche pattern, can be understood as a further development of the rule of symmetry under certain cultural, for example religious influences. The mirror symmetry is often reintroduced by doubling the motif, for example in the case of “double niche” carpets. More complex motifs such as human or animal figures can only be brought into harmony with the rule of symmetry if they are represented in an abstract form, stylized. Davies explains the rules of symmetry in detail using the Anatolian kilim as an example .

Self-complementing (reciprocal) patterns

Usually an image is seen in a context, for example a pattern on a background. A self-complementing (reciprocal) pattern is more complex, the predominance of the pattern over the background is canceled. An ornament can alternately become more prominent, or optically fade into the background, from which a new pattern develops at the same time, depending on how the perception is oriented. Simple examples of self-complementing patterns in oriental carpets are border patterns such as meanders , self-complementing “battlements” or “arrow” patterns, or a pattern known as a “running dog” that is often found in Anatolian and Caucasian carpets. Self-complementing patterns help ensure that a carpet pattern is experienced as dynamic, as the balance of the motifs is constantly changing.

Protection symbols

Symbols of protection against evil can often be found on Ottoman and later Anatolian carpets. The Turkish term for these amulets is "nazarlik" (literally: [protection from the] evil eye ). An apotropaic symbol is probably the Cintamani motif, which is often depicted on the white-ground “Selendi” carpets of the Uşak region and consists of three spheres and wavy ribbons. It serves the same purpose as protective inscriptions such as “May God protect”, which are also knotted into carpets. A triangular talisman pendant, the "mosca", is depicted in Anatolian, Persian, Caucasian and Central Asian carpets.

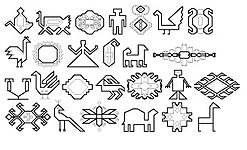

Tribal characters

Some carpets show symbols that are used like tribal coats of arms and make it possible to determine their origin from a tribe or ethnic group. This is especially true for Turkmen knotted textiles, which depict rows of different medallion-like polygonal patterns, which are known as "gül". The origin of these patterns can be traced back to images of the lotus blossom or the ancient Chinese "cloud collar" ornament in Buddhist art . However, it seems questionable whether these origins were still conscious.

Kufic borders

Ancient Anatolian carpets often have a geometric border design consisting of a sequence of repeated, long and short arrowhead-like ornaments. Because of their similarity to the Kufic letters alif and lām, borders with these ornaments are called "Kufic" borders. These two letters are supposed to represent a short form of the word " Allah ". Another theory associates this ornament with split palmette patterns. The "alif-lām" motif can already be found on the early Anatolian carpets from the Eşrefoğlu mosque in Beyşehir.

Symbolism of the prayer rug

The symbols of the Islamic prayer rug are easier to understand A prayer rug is characterized by the depiction of the prayer niche , which indicates the direction towards Mecca . Often one or more mosque lamps hang from the top of the arch, a reference to the verse of light in the Koran . Sometimes a comb or water jug is depicted as a reminder to wash and (for men) comb your hair before prayer begins. Stylized hands can be tied into the pile to indicate where the praying hands should be. These symbols are also known as "hamsa" or " hand of Fatima ", a protective amulet against the evil eye .

More detailed information on the origin of ornaments and patterns in oriental carpets can be found in the following publications.

- Valentina G. Moshkova: Carpets of the people of Central Asia of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Tucson, 1996. Russian edition 1970

- Schuyler Camman: The Symbolism of the Cloud Collar Motif.

- J. Thompson: Essay "Centralized Designs"

- James Opie: Tribal Rugs of Southern Persia, Portland, Oregon, 1981

- James Opie: Tribal rugs, 1992

- Walter B. Denny: How to read Islamic carpets ,

The Elibelinde motif: a forgery and its consequences

In 1967, the British archaeologist James Mellaart claimed to have discovered the oldest depictions of flatweaves on wall paintings in the Çatalhöyük excavations , which date back to around 7000 BC. To be dated. The drawings, which Mellaart claimed to have made before the paintings faded after exposure, show a clear resemblance to the patterns of 19th century Turkish flatweaves. He interpreted the forms, which were reminiscent of a female figure, as evidence of the cult of a "mother goddess" in Çatalhöyük. A well-known pattern of Anatolian kilims , the Elibelinde (literally: "hands on the hips"), he therefore determined to be the image of the mother goddess herself. After Mellaart's claims were unmasked and rejected by other archaeologists as fraudulent, the Elibelinde motif lost its divine meaning and its prehistoric origin. Denny understands the pattern as a stylized carnation blossom, the development of which he derives in detail and in uninterrupted lines from Ottoman court carpets of the 16th century. Brüggemann and Boehmer understand the motif based on their pattern structure analyzes as the “upper and lower vertical cross arm of the Anatolian form of the Yün-chien”, the Chinese “cloud collar” motif.

Variations of the "Elibelinde" motif

Age and dating

Determining the age of a carpet is important in order to understand the development of techniques and patterns in a particular region or design tradition. Possible approaches to determining age are:

- Data incorporated into the carpet itself or subsequently written down;

- Comparison of a carpet pattern with images of carpets in Islamic book illustrations and miniatures or on European paintings;

- Written records in archives or collections;

- Dating based on the circumstances of the find and with the help of other datable finds from archaeological excavations;

- Scientific analyzes of the material or colors used;

Carpets with inscriptions

Oriental carpets often have linked dates. These go back to the Islamic calendar and can be converted into the Gregorian calendar by subtracting three percent from the existing Islamic year and adding 622 to this number. In the year 622 the Islamic calendar begins with the hijra , the flight of Muhammad to Medina. Since 33 lunar years correspond to 32 solar years of our time calculation, 3% must be deducted. Conversion calendars are available.

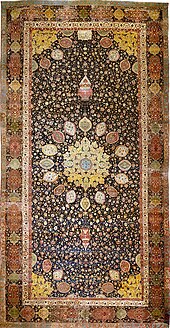

The oldest known carpets with a knotted year are the Ardabil carpets . Their inscription reads:

“I know of no other refuge in this world than your threshold.

There is no protection for my head but this door.

The work of the Maqsud Threshold slave from Kashan in 946 "

The AH year 946 corresponds to AD 1539-40, so that the Ardabil carpet can be dated to the reign of Shah Tahmasp I , who donated the carpets for the tomb of Sheikh Safi ad-Din Ardabilis in Ardabil , the spiritual father of the Safavid dynasty .

Another inscription is on the hunting carpet, which is kept in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan . Accordingly, this carpet was knotted in the year 949 AH / AD 1542–3:

“Through the care of Ghyath ud-Din Jami,

this famous work that touches us with its beauty was accomplished .

In the year 949 "

Usually date inscriptions on carpets cannot be clearly read. A carpet pattern may have been copied from an older carpet, the knotted date can even be changed and forged by replacing individual knots to make a carpet older and more valuable. Sometimes the numbers are illegible, because numbers that could not be understood because of illiteracy, were reproduced more like ornaments.

In rare cases, oriental carpets can be dated with inscriptions added later: Precious oriental carpets were part of the " booty from Turks " from the siege of Vienna , which was finally repulsed on September 12, 1683. The new Christian owners proudly reported in letters of their looting. There are still carpets preserved that contain inscriptions with the name of the new owner and the date they were taken into possession:

"AD Wilkonski XII septembris 1683 z pod Wiednia

AD Wilkonski, 12 September 1683, Vienna"

Particularly well documented are certain carpets that came from the Ottoman Empire to Western Europe via Transylvania and are known as Transylvanian carpets . As prestigious pieces of great value, they were valued by the inhabitants of Transylvania and donated in large numbers as church decorations, where they have been preserved over the centuries. Records from archives and inscriptions on the carpets themselves provide information about the dates of the acquisition or the foundation:

"TESTAMENTUM HENRICI KEYSER [...] DERSCH - 1661

estate of Heinrich Keyser [...] dersch - 1661

SUO SUMTU [...] MARTINI VAGNERI ANNO 1675

from Martin Wagner's own funds [...] in 1675

RECORD: ERGO [...] IN HON: DEI ET ORNAM: ECCLÆ: IOH […]

So […] donated to the glory of God and to adorn the church: Joh (an) "

Comparison with painted pictures

An important source for the art-historical classification of knotted carpets is their representation on Turkish and Persian miniatures and illuminations . The carpets known to us from the same period often differ so much from the images in Islamic art of that time that they often offer little starting point for a dating and classification of preserved carpets.

For lack of better information, in the early days of their art historical research, some Anatolian carpet types are named after the European painters who depicted them in their pictures, and they are dated according to the time when the paintings were created. According to this, a carpet is at least as old as the painting on which it is depicted. This method was invented by Julius Lessing , who in 1871 published his book “Old Oriental Carpet Patterns”. He mainly referred to European paintings and less to preserved carpets, because these were not yet specifically collected at the time and he assumed that hardly any copies had survived. For example, the “Lotto” and “Holbein carpets” got their names from the Renaissance painters Lorenzo Lotto and Hans Holbein , who depicted a number of these knotted carpets in their works. The terms remained in use as more precise information became available because their catchiness made it easier to understand each pattern type. The method of dating by comparison with European paintings was developed by scientists from the “Berlin School”, Wilhelm von Bode , Friedrich Sarre , Ernst Kühnel and Kurt Erdmann . As a result, a carpet is at least as old as the painting on which it is depicted. The painting gives the term ante quem for dating. Since this method can only be used to date carpets that had come to Europe and that could serve as a model for the painters, the method does not help in determining the age of flat woven fabrics and the carpets of the village and nomadic tradition, which are of interest to art historians. For the most part, only carpets are shown in these pictures, which came to Europe as trade goods mainly from Anatolia. In contrast to the Anatolian carpets that are well documented in this way, they appear before the 17th century. no Persian carpets depicted on European paintings.

Written records

The written sources for a more precise dating and determination of origin become richer during the 17th century. With the intensification of diplomatic exchanges, Safavid carpets came more often as gifts to European cities and states. In 1603, Shah Abbas I gave the Venetian Doge Marino Grimani a carpet with woven gold and silver threads. European aristocrats began to order carpets directly from the Isfahan and Kashan factories, which were able to knot special patterns, such as European coats of arms, into the carpets. Occasionally the acquisition is exactly understandable: In 1601 the Armenian Sefer Muratowicz was bought by the Polish King Sigismund III. Wasa sent to Kashan to order eight carpets with the knotted coat of arms of the Polish ruling family. On September 12, 1602, Muratowicz was able to present the king with the carpets and his treasury with the invoice for carpets and travel expenses.

In 1633 Evliya Çelebi , who was in court service with Sultan Murad IV. Reports that there were 111 carpet dealers in the guild of Istanbul and mentioned forty shops in which carpets from Izmir, Thessaloniki, Cairo, Isfahan, Usak and Kavala were sold. Last but not least, there are inventory lists from monasteries, castles, museums, rulers and private estates that have been preserved in large numbers, which list carpets and at least prove a respective minimum age of the items given in the lists. However, the place of origin - even with some famous carpets - is sometimes controversial because the inventory lists often only offer imprecise descriptions. On the death of Archduke Charles II in 1590, the Habsburg estate registers included the unhelpful entry “Türggische fuestepich, gross and klain, three”.

Inventories from Venice , in particular , which had close trade relations with the Ottoman Empire and Persia since the early 14th century, offer more differentiated records . The trade names used by the Venetians provide no information about the structure or pattern of carpets: Mamluk carpets from Cairo were called “cagiarini”, those from Damascus “damaschini”, “barbareschi” came from North Africa, “rhodioti” and “turcheschi” from Ottoman Rich, and carpets from the Caucasus were known as simiscasa .

Archaeological finds

The few surviving earliest carpet fragments and carpets such as the Pasyryk carpet can be dated based on the circumstances of the finds and in comparison with other finds in the same place. Due to the material used, archaeological finds of textiles are very rare. Centuries-long gaps between the individual finds do not allow continuous dating, but rather highlight individual, very old specimens.

Scientific analyzes

With the invention of spectroscopy , chromatography and the radiocarbon method , the analysis and age determination of organic materials improved. These methods are also used with carpets. Spectroscopy and chromatography are particularly helpful in determining colors. If synthetic colors are found in a carpet, it cannot be older than the dyes used from the second half of the 19th century . If indigosulphonic acid is found, the wool could not have been dyed until the first half of the 19th century at the earliest. The methods were also important in determining natural colors by comparing them to the pigments used to dye antique carpets. A carpet can be assigned to a region by providing evidence of specific color pigments for a geographic region.

The radiocarbon method has proven particularly useful for determining the age of antique carpets. Unfortunately, the method shows considerable inaccuracies for material that is younger than AD 1200, so that with its help only an age range that is often too broad can be given. A further development of the radiocarbon method, accelerator mass spectrometry , was also used with Anatolian flat fabrics with contradicting results. All scientific analyzes are complex and expensive and are therefore only available to a limited extent.

Four social classes: court and town manufactories, villages and nomads

According to the academic tradition of the “Vienna School” around Alois Riegl , every artistic production experiences a high point and a subsequent decline. According to this, a carpet knotted by nomads, for example, would represent only a degenerate modification of the design of court and town manufactories. Kurt Erdmann recognized that the different structures and patterns each originate from independent traditions from four social classes and must be viewed separately from one another: carpets of different styles were made at the same time by and for the royal court, in commercially oriented factories in the big cities, but also knotted by the inhabitants of rural villages and nomadic tribes for their own needs and trade.

The sophisticated patterns of the court and town manufactories are picked up by the village and nomadic knotters and integrated into their own pattern tradition through an active process of appropriation known as stylization . When carpets are intended for retail, they reflect the needs of the customers and also have patterns that do not come from their own tradition in order to meet special requests. This adjustment of production to the export market had in the past destructive effects on the traditional pattern traditions. On the other hand, the interest in traditionally manufactured carpets supported the revival of the old traditions in recent years.

The workshops of the ruling court

Four great empires shaped the history of the Islamic world: the Persian , Ottoman , Mamluk and Mughal empires . The need of the rulers for representative art objects led to the establishment of specialized workshops, the court manufactories, in all four realms. In mutual influence, these developed both new patterns and forms as well as new work processes. For the knotted carpet, this meant a fundamental change in its artistic design, which later also had an impact on traditional carpet production in cities, villages and nomads. In addition, the court manufactories introduced a division of labor: while the weavers had previously designed and executed the motifs and patterns of their own carpets according to their own traditions, in the court and large city manufactories artists were responsible for the design, which was then sent to the craftsmen in the form of a knot pattern Execution was committed.

Characteristic for the production of the court and larger city manufactories are the use of precious materials such as silk or gold and silver broochings, as well as the development of artistically designed, often fine and complicated patterns. The court manufactories thus distinguish themselves from the local traditions of the villages and nomads. From the need to represent their own power, their patterns develop an independent formal language that is more based on the production of the court manufactories in neighboring countries than on the pattern traditions of their own country. In some cases this exchange between the countries is documented: For example, on the orders of Sultan Suleyman I, Persian artisans from Tabriz were ordered to the Ottoman court. They introduced the Ottoman artisans to Persian art, which had flourished at the Safavid court . Sultan Murad II ordered eleven carpet masters from Cairo to Istanbul in 1585 and expressly urged them to bring the necessary wool with them. The Mughal ruler Akbar I not only imported Persian carpets, but is also said to have asked Shah Abbas to have master knotters to establish factories in Agra and Fatehpur Sikri , the two capitals of his empire, as well as in Lahore.

Kurt Erdmann wrote:

“Carpets were so vital to the furnishing of their large tents that kings, generals, and other important men carried them with them when they went hunting or traveling, even when they went to war. When a ruler traveled at that time, the most sophisticated means were used to make his tent as comfortable as his palace. Nothing was to be missing and a whole army of servants traveled ahead of their ruler, so that they had enough time at the destination to pitch the huge tents, which were actually portable palaces with many rooms, furnished with every imaginable luxury and with many beautiful carpets . In some cases, streams have been diverted and gardens with fountains have been created. Even trees were carried along as well as the menagerie of the gentlemen. "

The Ottoman court manufactories

After the conquest of Constantinople , the city as the new capital of was the Ottoman Empire expanded . In the court workshops ( Ehl-i Hiref ) artists and craftsmen of different art styles worked. Calligraphy and book illumination were practiced in the scriptorium, the nakkaşhane . The illuminations and ornaments designed there, also under the influence of the Safavid court art, also influenced the patterns of carpet weaving. Besides Istanbul, famous centers of Ottoman handicrafts were mainly Bursa, Iznik, Kütahya and Uşak. As the “silk city”, Bursa was famous for silk fabrics and brocades, İznik and Kütahya for fine ceramics and tiles, and Uşak especially for carpets.

Some Anatolian types of carpets, such as the “Holbein” and “Lotto” carpets, which have been exported to Europe in large numbers, come from the city manufacturers in the Uşak region. European kings, nobles and, imitating them, wealthy citizens of the Renaissance period liked to be depicted on and with Anatolian carpets. At the beginning of the scientific research into the history of Islamic art, preserved carpets were not known in as large numbers as they are today, which is why the carpets were initially divided into groups based on European paintings , which were named after the painters on whose paintings the carpets could be recognized.

Due to the distribution and size of the geometric medallions, the Holbein carpets with large and small patterns differ . In the case of the latter, small octagons, often containing a star, are distributed in regular rows across the field and are enclosed by geometric arabesques. The Holbein carpets with large patterns show two or three large octagons that often enclose eight-pointed stars. The field is dotted with tiny blue floral patterns. Two examples from the 16th century are in the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna and in the Louvre in Paris.

The lottery carpets have a yellow grid of geometric arabesques on the mostly bright red, rarely also dark blue field, with cross-shaped elements alternating with octagonal or diamond-shaped elements. The oldest pieces from the end of the 15th century have a Kufi border. The whole area of the field is covered by bright yellow foliage based on a repeat of diamonds and octagons . The carpets were made in all sizes up to a length of six meters.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the “ Turkish Baroque ”, which was shaped by French art, developed . Carpets were created based on the model of the French Savonnerie and Aubusson manufactories. Sultan Abdülmecid I (1839–1861) began building the Dolmabahçe Palace , the “Palace of the Heaped Gardens”. 60 km from Istanbul, near the city of Izmit, he founded the royal court manufactory in Hereke in 1844 . The Hereke Manufactory originally only produced fabrics and carpets that were intended for the furnishing of the Ottoman court, especially the newly built Dolmabahçe Palace. Only later were the products available on the general market. The Hereke court manufactory is therefore the only workshop that was demonstrably planned as a “court manufacture” in the narrow sense of the word.

The workshops of the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate

The name Mamluken goes back to slaves of Turkish-Caucasian origin who performed military service under the rule of the Aijubids in Egypt and Syria, seized power there in the 13th century and defended it until the Ottoman conquest at the beginning of the 16th century. They created an empire that included Egypt , Palestine , Syria and the Hejaz . Until 1517, the Mamluk sultans exercised the patronage of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina as caliphs and guaranteed the safety of the pilgrim caravans from Cairo and Damascus on the annual Hajj .

In Cairo , Damascus and Jerusalem, as well as in smaller trading centers, marketplaces ( souq , barge ) and rest stops for trade caravans ( caravanserai , Wikala ) emerged. The Mamluk sultans stimulated production in the workshops of their dominion through commissions. As a result, the handicrafts achieved high material and design quality. Edmund de Unger proved that the carpet patterns of the Mamluk manufactories are very similar to the decorations on other products of the Mamluk workshops, and concludes from this that the craftsmen influenced each other.

The Mamluk rulers maintained diplomatic ties to the southern European powers Castile and Sicily, the Italian republics and Byzantium, as well as to the Mongols and the Far East. Diplomatic and trade relations between the Republic of Venice and the Mamluk dynasty date back to the early 14th century. In 1983 two Mamluk carpets owned by the Medici were found in the depots of the Palazzo Pitti in Florence and another in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco . Carpets of this type were known in Venice under the name "tappetti damascini". They were depicted on paintings and frescoes by European artists of the Renaissance period. Kurt Erdmann proved that these carpets were made in Cairo.

From the time of the Mamluk rule, carpets of particular character have been preserved. They show filigree geometric patterns, the main element of which is a central medallion, which consists of an octagon, a square and a diamond, which are superimposed on one another, so that the impression of an eight-pointed star is created. The color palette is very economical, mostly bright red, green, light blue with a little yellow and white. A key feature of these carpets was the lack of contrast between the border and the midfield pattern. Unique to Islamic carpets, the Egyptian workshops used clockwise ("S" -) spun wool that was twisted counter-clockwise ("Z" -). Preserved documents show that knotted carpets were produced and traded in Cairo between the 2nd quarter of the 14th century and the 1st quarter of the 17th century.

After the conquest by the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Marj Dabiq near Aleppo and the Battle of Raydaniyya near Cairo , two different cultures merged, which is also very clearly evident in local carpet production after this period. After the conquest, Ottoman patterns found their way into the carpets, which were still spun and twisted using the old technique. Carpets whose patterns show influences from both cultures are referred to as "Cairene Ottoman carpets". Cairene Ottoman carpets are characterized by complicated and densely designed floral motifs in Mamluk colors. In later times, central and corner medallions also appear in the Persian-Turkish tradition. The cultural change is particularly noticeable in the design of the main border: the traditional Mamluk border pattern consisting of cartouches and rosettes is being replaced by rosette and ribbon patterns from Anatolian-Persian tradition. They continued to be made in both Egypt and probably Anatolia into the early 17th century.

Mamluk carpet, around 1500, from the Friedrich Sarre collection , Berlin

Cairen Ottoman carpet, 16th century, Museum of Applied Arts Frankfurt St. 136

The Safavid court manufactories

In the Persian Safavid Empire , court manufactories were probably established in Tabriz by Shah Tahmasp I , but certainly by Abbas I when he moved his capital from Tabriz in the northwest to Isfahan in central Persia during the Ottoman-Safavid War (1603-18) . For the art of carpet-knotting in Persia, this meant, as AC Edwards wrote: "That it rose from village level to the dignity of a high art in a short time".

Under the influence of painters and miniaturists from the Herat and Tabriz schools, such as Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād , a canon of forms of representative patterns and ornaments emerged, which probably found their way into carpet-making at the beginning of the 16th century. Whereas the carpet weavers had previously also designed the patterns themselves, now artists were responsible for the designs, which were then handed over to professional knotters for execution. Node numbers of over a million per square meter allowed the display of the finest details; silk thread was used for this. Particularly valuable carpets contained weft threads wrapped in gold and silver stripes.

Shah Abbas I promoted trade with Europe, especially with England and the Netherlands, which were in demand for Persian carpets, silk and textiles. Shah Abbas saw the rulers of Christian Europe as potential allies in his conflict with the Ottoman Empire . Luxury goods such as silk and carpets were exchanged for gold and silver, which at that time came to Europe in abundance with the silver fleets from South America.

The "Polish carpets" (also called Shah Abbas carpets) represent a special group of precious carpets that were probably made in Kashan on behalf of the court . These carpets, the weft threads of which were often wrapped with gold or silver foil, served as representative diplomatic gifts from the Safavid rulers to other rulers. Shah Tahmasp I presented the Ottoman Sultan Selim II with a carpet for his accession to the throne. Spain was represented at the Persian court by religious, and James I of England sent Sir Dodmore Cotton to Isfahan. King Sigismund of Poland sent traders to Persia to buy carpets. The French King Louis XIV also sent weavers to Persia to learn the art of knotting there.

In the Museo San Marco in Venice five curtains are exhibited. The exact date of their acquisition is unknown. All knotted from silk and broached with gold and silver thread, they are considered to be some of the earliest pieces of their kind made in Isfahan in the late 16th century.

The workshops of the Mughal Empire