Venice

| Venice | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Country | Italy | |

| region | Veneto | |

| Metropolitan city | Venice (VE) | |

| Local name | Venezia (Venè (s) sia / Venèxia) | |

| Coordinates | 45 ° 26 ' N , 12 ° 20' E | |

| height | 1 m slm | |

| surface | 414.573211 km² | |

| Residents | 259.150 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Post Code | 30100 | |

| prefix | 041 | |

| ISTAT number | 027042 | |

| Popular name | Veneziani | |

| Patron saint | Markus (April 25) | |

| Website | www.comune.venezia.it | |

Grand Canal as seen from the Ponte dell'Accademia |

||

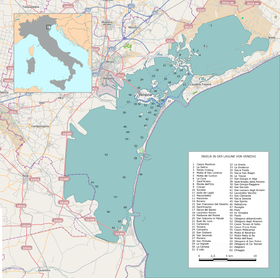

Venice ( Italian Venezia [ veˈnɛʦːi̯a ], Venetian Venesia [ veˈnɛsja ]) is a city in northeast Italy . It is the capital of the Veneto region . The metropolitan city of Venice is nicknamed La Serenissima ("The Most Serene"). The historic center (centro storico) is located on more than 100 islands in the Venice lagoon .

The total area of Venice is 414.6 km², of which 257.7 km² is water. On December 31, 2019, the city had 259,150 inhabitants, of which 179,794 in the districts on the mainland, 52,996 in the historic center and 27,730 within the lagoon. The lagoon extends for about 50 km between the mouths of the Adige ( Etsch ) rivers in the south and Piave in the north into the Adriatic Sea .

Venice was the capital of the Republic of Venice until 1797 and one of the largest European cities with over 180,000 inhabitants. Up until the 16th century it was one of the most important trading cities, through which most of the trade between Western Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean was carried out. Venice maintained most of the merchant and warships. The respective doge was elected head of state in a complicated electoral process, first by the popular assembly, then by the urban nobility . The latter monopolized the higher offices and profited from trading in luxury goods, spices, salt and wheat, while the rest of the population was largely excluded from long-distance trade. Venice developed into the largest financial center and dominated a colonial empire that stretched from northern Italy to Crete and at times to Cyprus . After French and Austrian rule between 1798 and 1866, Venice became part of Italy. In 1929 the industrial complex Mestre - Marghera was incorporated into the Comune di Venezia , just like most of the places in the lagoon before. The Jewish part of the population was deported to Germany during the Second World War by the National Socialists , who occupied Italy, and most of them were murdered. By 1950, the number of residents of the historic center increased to around 185,000 due to war refugees. In the years 1965 to 1970 the city as a whole had the highest population with almost 370,000 inhabitants. Since then, it has decreased by more than 100,000 (January 2021: 255,609).

Venice and its lagoon are on the since 1987 UNESCO list of World Heritage . They particularly inspired the artists and Venice became one of the most visited cities by tourists. For a century, the economic structure of the old town has been one-sidedly geared towards tourism , while industrial activity is mainly concentrated around Mestre and Marghera on the western mainland.

geography

geology

The settlements that made Venice lie on alluvial land that was created by post-glacial rivers. The lagoon created in its estuary covers an area of about 550 km² and is delimited from the Adriatic by about 60 km long sandbanks. Only about three percent of this area is covered by islands, the rest consists of mud flats and marshland, the barene , which cover over 90 km², then about 92 km² of fishing grounds, the Valli da pesca . The barene are criss-crossed by natural canals called ghebi. Around 1900 the Barene covered more than 250 km². In contrast to the often flooded Barene, the Velme, shallows, have only little vegetation because they only appear when the water level is very low.

The lagoon was formed from around 4000 BC. By deposits of the Brenta and other rivers and streams in northern Italy. These river sediments cover a lower Pleistocene layer of clay and sand that is between 5 and 20 m thick. During the last glacial period , the sea level was about 120 m below the level of 2012, but rose to around 5000 BC. At 110 m. Since then, the water level has continued to rise slowly with strong fluctuations.

Around AD 400, Venice was still around 1.9 m below sea level in 1897. From the High Middle Ages , the lagoon was exposed to profound changes, such as the diversion of tributaries to regulate the water level and avoid silting up. Since the early 20th century, numerous canals have been deepened and widened, bringing significantly more salt water into the lagoon and increasing current speeds.

climate

The city is located in the temperate climate zone . The average annual temperature is 13.5 ° C. The warmest months are July and August with an average of 23.1 and 22.6 ° C, respectively, the coldest month is January with 3.0 ° C. The average maximum daily temperature in July and August is 27 ° C. The Venetian lagoon is shaped by the maritime climate of the northern Adriatic . This explains the precipitation peaks in the course of the onset of late summer, since at this point in time the continental climate from the Eastern European mainland, in particular the Carpathian Mountains ( Bora winds ) and the subsequent reversal of the weather situation from the south side of the Central European Alps . The average annual precipitation is 770 mm. Most precipitation falls in November with an average of 86, the lowest in January with an average of 53 mm.

| Venice | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Venice

Source: wetterkontor.de

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

The northern part of the 550 km² large lagoon contains mainly fresh water and is hardly affected by the tide change , which reaches around 418 km². It is therefore called Laguna morta (dead lagoon). The salt water lagoon, whose water level falls and rises with the ebb and flow of the tide and which is washed more strongly by seawater, is called Laguna viva (living lagoon). The Barene provide a favorable habitat for a large number of species, but they have been greatly reduced in size. In 1900 they covered 20 percent of the lagoon area, in 1930 it was only 13 percent, and now it is only 47.5 km². When another industrial area was to be developed in the 1960s, the Casse di colmata , as they were called, were withdrawn from any commercial use in order to develop them into an industrial area. Large amounts of mud and concrete were poured in there, creating new islands that protruded an average of 2 m above the water. But the project came under fire after the catastrophic flood of November 4, 1966, was stopped in 1969 and finally ended in 1973. In the meantime, these areas have become of great importance for migratory birds, their core covers 11.54 km². The World Wide Fund For Nature declared the area to be one of the most important protected areas for migratory birds in Europe, including the fishing grounds.

The flora and fauna of the Venetian waters are characterized by great biodiversity. Therefore, here eel , mullet , sea bass , sea bream and other fish species on the market. They come from the lagoon's fishing grounds, where birds, mammals and reptiles also live.

Over 60 species of birds breed in the lagoon alone. On stationary birds are found mallard , marsh harrier , moorhen , coot , snowy plover , tern , Beutelmeise , as well as purple heron , night heron , redshank and grebes . Great crested grebes and black-necked grebes , great egrets and various ducks also spend the winter here . More than half of the dunlins who winter in Italy do so in the lagoon.

Mammals include the harvest mouse , water shrew , polecat , stone marten , large vole , mouse weasel , but also brown-breasted hedgehog . The yellow-green angry snake , grass snake and dice snake also live here . There are also numerous species of insects and spiders.

There are numerous species of plants from the genera of samphire , sea lavender and salt plumes . The vegetation below the water level is formed by two communities of seed plants that are of great importance for duck birds, namely dwarf seaweed , which belongs to the seagrass, and the seaweed , which belongs to the balances and which is found mainly in areas with lower salt concentrations finds stable ground. There are also reeds , cattails, especially the broad-leaved cattail species . Most of these species live in the fishing grounds, not in the open lagoon, because the swamps (paludi) have been largely destroyed. For several years there has been discussion about the partial opening of the Valli in order to spread the species present there again outside the fishing grounds.

Of the original forests, only the park of Villa Matter in Mestre and the 230 hectare forest of Carpenedo remain. There are mainly hornbeam and English oak to be found there . Mestre is now surrounded by forests, including the Bosco dell'Osellino, the Bosco di Campalto and the Boschi Ottolenghi. In 1984 the population turned against the construction of a hospital directly opposite the Carpenedo forest and gradually pushed through the expansion of the forests. In addition, the huge rubbish dump between Mestre and the lagoon, which covers an area of 7 km², will be converted into a park, the Parco San Giuliano. There is also the Parco Albanese between Mestre and Carpenedo, which covers 33 hectares.

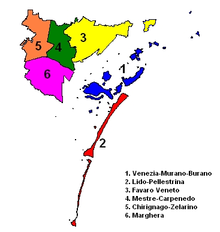

Expansion, location and administrative structure

Venice is the capital of the metropolitan city of Venice , which emerged from the Province of Venice on January 1, 2015. The city of Venice comprises the historic center with an area of around 7 km² and most of the Venice lagoon with its more than 60 islands (1). In addition, there are the elongated islands of Lido and Pellestrina (2), which demarcate the lagoon from the Adriatic Sea, as well as the mainland districts of Favaro Veneto (3), Mestre (4), Chirignago and Zelarino (5) and Marghera (6).

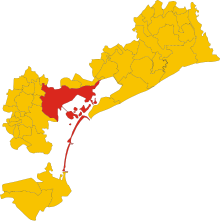

The city has been divided into six districts or Municipalità since 2005 . The Municipalità Venezia-Murano-Burano (1) includes the historic center, i.e. what is often called the old town in German. This in turn is subdivided into six sestieri , three of which are to the left and right of the Grand Canal, which flows through the old town in the form of a broad question mark from west to east. In the direction of flow to the right, approximately to the west and south of the Grand Canal, are the three Sestieri San Polo , Dorsoduro , which also includes the islands of the Giudecca on the southern edge of the old town , and Santa Croce . On the left, generally east and north of the Grand Canal, lie the Sestieri San Marco , which also includes the island of San Giorgio Maggiore , Cannaregio and Castello . Traditionally, the sestieri to the left and right of the canal were designated from the viewpoint of the Doge's Palace , that is, the sestieri on this side of the canal were designated as citra (this side), those on the other side of this main waterway as ultra . In addition to the six sestieri of the old town, the district includes the central and northern part of the lagoon with numerous islands, the most important of which are the glassblower island Murano , the northeastern island trio Burano , Mazzorbo and Torcello as well as the vegetable islands Sant'Erasmo and Vignole .

The Municipalità Lido Pellestrina contrast, occupies the eastern part of the lagoon with that of Chioggia to Jesolo reaching Spit one who enters into the lagoon to the Adriatic Sea through. The two long, narrow sandbanks extend over 20 km south of Venice. The northern Lido di Venezia developed into a fashionable seaside resort with luxurious hotels and a casino in the 19th century ; Pellestrina , on the other hand, lives mainly from fishing and mussel fishing. Chioggia, on the southern edge of the lagoon, does not belong to Venice.

In addition to these two island municipalities, there are four more on the mainland. The Mestre-Carpenedo district was incorporated into Venice in 1926 and is home to more than half of the city's residents. Attempts to outsource Mestre from the Venice municipality failed in five referendums. After 2003 (48% for the division), another referendum failed on December 1, 2019. The turnout was extremely low at 21 percent, the Lega and five-star movement initiated the referendum. The industrial district of Marghera is also on the mainland and is characterized by the petrochemical industry. The district of Favaro Veneto is located northeast of Mestre and includes Marco Polo Airport . The Municipalità Chirignago-Zelarino includes the districts Chirignago , Cipressina , Zelarino , Trivignano and Gazzera , the western suburbs, and is the only Venetian Municipalità that has no access to the lagoon.

Structure of the old town

The old town of Venice is made up of 118 islands with canals of different widths running between them . Many of these islands have a communication, traffic and trade center with a parish church. However, changes from the early 19th century onwards overlaid this structure, such as the construction of the wide Strada Nova or the Via Eugenia (now: Via Garibaldi).

Function assignments

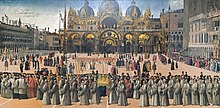

In addition to this basic structure, some districts have very different structures due to various historical functions, for example around St. Mark's Square, the former center of power and representation of the city. The largest square in the city, 175 m long and up to 82 m wide, is characterized by the adjoining state buildings, in particular the Doge's Palace and the Procuraties . There are also libraries and museums, the Markuskirche and the Campanile , but also four large cafés. On the other side of the Grand Canal, Campo San Polo is the largest square.

In the east, the arsenal , in which the shipbuilding industry, which is important for Venice, was located and is the restricted military area, has more area than St. Mark's Square . Its surroundings have typical characteristics of an industrial district, in this district over 10,000 workers were employed at times. Ship production there is reminiscent of "industrial assembly line production in terms of its principles of standardization and systematization". The workers lived around the arsenal in this largest factory of the Middle Ages, the "arsenalotti".

Since the middle of the 19th century, the west of the city has been most strongly characterized by the connection to the mainland. This is where the large bridge to the mainland joins, the Ponte della Libertà , which was built in 1931 as a road bridge next to the railway bridge completed between 1841 and 1846. The train station expands at its head , at the end of the Ponte della Libertà there is a parking garage and a bus stop in Piazzale Roma . Further south-east, a track ends at the Stazione Marittima, from which the rail freight traffic is connected to the small port. In addition, with Tronchetto, an artificial park island over 18 hectares was raised.

On the south side of the city, the Zattere extend from the aforementioned Stazione Marittima in the west to the Grand Canal, then further eastwards the Riva degli Schiavoni from the Doge's Palace to the site of the Biennale . This south side is used as a promenade. The same applies to the opposite north side of the Giudecca , which is almost the only one that still has industrial structures, such as the Stucky mill . This building was built in 1895 according to the plans of the architect Ernst Wullekopf from Hanover .

The more mixed social structure has been preserved in many neighborhoods, but some of them have developed into slums, such as Sacca Fisola . The area around the Arsenal to Via Garibaldi can be seen as a typical working-class district. Although the Serenissima often settled members of different nations in their own streets, as can often be read from the names of the streets (Calle dei Greci, etc.), little of this division can still be felt. Only the ghetto , the quarter in which the city's Jews lived from 1516 to the early 19th century, has its own structure and construction of the houses. All Venetian Jews were forced, divided into "nations", to live there. In addition to them, the commune had an impact on local conditions through the responsible office holders, the Cattaveri, but also the Christian owners of the houses and wells where the Jews lived for rent - as the decree of March 29, 1516 expressly states, should the previous tenants leave their houses and the new tenants pay a rent that is one third higher. This soon resulted in houses with up to eight floors, often with very low ceilings. In addition, the living conditions were very cramped overall - in 1552 there were 900 residents in an area of around three hectares, in 1611 there were 5500 - the ghetto soon had to be expanded. From 1633, next to Ghetto novo and Ghetto vecchio, Ghetto novissimo (the new, old and newest ghetto) was created.

Streets with the same functions were already established here and there in the late Middle Ages, such as in the area of the Rialto Market and around the Carampane , the former prostitute's quarter , around the arsenal and the Doge's Palace, but this was difficult to reconcile with the island structure. The dominance of water traffic is evident on the Grand Canal, which is only partially accessible by pedestrians. This is especially possible around the Rialto Bridge, the former commercial center of the city. Instead, the representative palace buildings of the city nobility, the palazzi or case (houses) (hence names such as Ca 'Foscari) , have been clustered on the canal since the late Middle Ages . These cases were owned by large families of the same name, such as the Contarini, but they fell into several dozen branches that had little to do with each other. Therefore, their palaces are not only referred to with Ca 'Contarini, but also more closely with the name of the associated parish, sometimes the name of later owners or conspicuous features. This is how names come about like Palazzo Barbarigo della Terrazza (it has a large terrace) or Palazzo Grimani di San Luca, which was built in the 16th century in the parish of St. Luke.

Around this core area of the city are numerous islands, which were assigned various tasks as early as the Middle Ages: a cemetery island ( San Michele ), one for the glassblowers ( Murano ) or one for the production of vegetables ( Sant'Erasmo ), others were used for military security Lagoon.

House building

The places in the lagoon were built on millions of wooden stakes that were driven into the ground. It was discovered early on that under the mud deposit there was solid clay soil, the caranto (late Latin caris, rock) and that buildings could be built on stakes that were driven into this layer. The so-called zattaron, a kind of pontoon made of two layers of larch planks, which were attached with bricks , rested on this first level . The foundation walls and finally the above-ground masonry are supported on the Zattaron. In order to save weight, the buildings themselves were built from light, hollow clay bricks, the mattoni.

Despite visible efforts, many buildings are in poor condition. The reasons for this are, on the one hand, the rise in the water level, which makes the bottom floor of most buildings uninhabitable. On the other hand, maintenance measures on buildings and canals have been neglected since the end of the Republic of Venice . The currents in the lagoon, triggered by the ebb and flow of the Adriatic, were reinforced by the dredging of deep channels for the overseas ships heading for the port of Marghera, so that the foundations were washed away. After all, apartments in the old town are considerably more expensive than on the mainland and are therefore often uninhabited.

Streets, alleys and squares

The Venetians very carefully differentiate between footpaths and squares. The main streets Rughe (from the French rue ) and the Salizade, the first cobbled streets from the second half of the 13th century, are limited in number. The narrow streets are called calle and the streets along the canals, which also serve as the foundation for the buildings, are called fondamenta . Lista is the part of the way near the important palaces and embassies, which enjoyed a special immunity. Mercerie are the streets with shops (merce = goods), the Rive (shores) run along the side channels. A rio terà is a filled-in canal, a ramo (branch) is a short street that branches off from a calle or a campiello , a small square. A campo is a place with a church, a larger open space that used to be a vegetable garden or pastureland for horses. Campiello is a square surrounded by houses, onto which the Calli flow, Corti are the inner courtyards of the houses. Paludo recalls that this area used to be swampy , instead of the pissins there were ponds where you could swim and fish. The Sotoportego goes under the houses ( the room on the first floor is called Portego , so the path leads under this room) and connects Calli, Campielli and Corti .

The squares (campi) and cookies (campielli) are differentiated from the piazza, with which the Piazza di San Marco, St. Mark's Square , is meant, even if there was a Piazza di Rialto . Just as Piazza means St. Mark's Square, the Piazzetta refers to the square in front of the Doge's Palace , which connects St. Mark's Square with the Molo, the landing stage at the lagoon. The Piazzetta dei Leoncini is the part of St. Mark's Square north of St. Mark's Basilica, named after the two lion figures that are erected there. The square with the bus station, however, is called Piazzale Roma . There is only one single street, the Strada Nova, plus three vie (Via 25 Aprile, Via Vittorio Emanuele and Via Garibaldi).

Canals and bridges

Venice has around 175 canals with a total length of around 38 km. The main artery is the Grand Canal , and there are also many waterways outside the historic center. The tide difference used to be 60 cm. A system of water regulation ensured a constant circulation that purified the city and the water. The canals were originally designed to be about 1.85 m deep. From the end of the 18th century, however, they were no longer cleaned until the 1990s. In addition, numerous canals have been filled in or shut down since the 18th century, which can often be seen from the name “rio terà”. The broad Via Garibaldi, for example, was created by filling in a canal, and in 1776 the Rio de le Carampane was filled in. There is a small square there.

There are 398 bridges in the city . Until about 1480 they were mostly made of wood, later they were replaced by stone bridges. In the meantime only two of them are without a railing, one of them is the Devil's Bridge (Ponte del Diavolo) on the island of Torcello , the other opens up a private house in Cannaregio (3750). Many were built very flat in order to make them accessible or drivable for horses and carts. The Rialto Bridge was the only bridge over the Grand Canal until the middle of the 19th century. In the meantime, three more have been added, namely the Ponte degli Scalzi near the train station, which replaced an iron previous bridge from 1856 in 1932, and the Ponte dell'Accademia at the eponymous cultural institute , which was established from 1854 and was replaced in 1933. A fourth bridge, the Ponte della Costituzione , was inaugurated in 2008. This bridge connects Piazzale Roma with the bank (Fondamenta S. Lucia) east of the Santa Lucia train station .

One of the most famous bridges, the Bridge of Sighs (Ponte dei Sospiri), connects the former state prisons on the ground floor, the so-called Pozzi , with the Doge's Palace. The straw Bridge (Ponte della Paglia), which spans the Rio di Palazzo at the Doge's Palace, is so named because there docked laden with straw boats. Other bridges are named after the spanned Rio, a nearby palace or church, often after a saint. The name Ponte storto, which appears ten times in Venice, refers to a bridge that crosses a Rio diagonally.

The bridge over the Grand Canal, which connects the churches of Santa Maria del Giglio and Santa Maria della Salute , is a specialty of the year on November 21st . A procession takes place on it in gratitude for the redemption from the plague of 1630/1631. The same thing takes place on the Saturday before the third Sunday in July with the building of a bridge over the Canale della Giudecca to the church of Il Redentore . With this Festa del Redentore one expresses one's gratitude for the salvation from the plague of 1575/1576.

By far the longest pair of bridges forms the only dry connections from the mainland to the islands of the Centro Storico: The railway bridge (Ponte Vecchio, Old Bridge, Ponte della Ferrovia) was built between 1841 and 1846, connecting the Mestre train station with the Santa Lucia train station (in the district Cannaregio) in the Centro Storico. It is 3605 m long. It is electrified and has an island with trees roughly in the middle on its northeast side. The road bridge, which was not built until 1931 to 1933, largely very close (southwest) and running parallel, was renamed the Liberty Bridge ( Ponte della libertà ) after the Second World War , in memory of the liberation from fascism. It is 3,623 meters long, connects Mestre with Cannaregio and Santa Croce and rests on 222 stone arches. (The total length of 3850 m according to Structurae includes the right curve to Santa Croce.)

Structures of mainland cities

The cities on the mainland, which are much larger in area, appear considerably younger than the lagunar towns, even if Mestre , Chirignago , Gazzera , Asseggiano , Carpenedo , Zelarino or Favaro have their own historical centers . However, they are often overlaid by industrial structures and settlement and building forms of the 20th century . Their expansion took place mostly along traffic routes, such as the railway lines and arterial roads, but also in the vicinity of large clinics and company settlements, so that a structure called "confused" emerged. The result was an extremely inconsistent cityscape, which is also heavily affected by traffic flows and noise, for example from the airport. Therefore, city bypasses are to be created to relieve the local centers.

Despite the often unsystematic urban structures, the mainland cities, which date back to antiquity and the early Middle Ages, have central urban elements that are constitutive for Italian cities. For example, there are central squares and town halls. The center of Mestre is the Piazza Ferretto near the Marzenego river , the former fortress city can still be seen in the streets. Marghera, on the other hand, was right on the edge of the lagoon , so that it had similar waterway networks as the islands, which also applies to Favaro. There was also a Palazzo municipale, a town hall, built in 1873 on Piazza Pastrello. Similar to Mestre, Chirignago was an independent municipality (1798 to 1927) and was incorporated into Greater Venice at the time of the fascists. In the Second World War, however, the place was largely destroyed, mainly by the bombings of October 6, 1943 and March 28, 1944.

history

Early settlement

The early settlers on the islands of the lagoon, whose traces can be traced back to the Etruscan period, now even as far as the Neolithic , came from northern Italy during the migration of peoples . The Venetians who lived here gave their name to the Venetia region .

Byzantine outpost

Ostrogoths, Lombards and Franks occupied Italy, but from around 540 the places in the lagoon remained the westernmost outpost of the Byzantine Empire . They developed their own ruling structure with tribunes and, according to legend, from 697 onwards, a doge at the head. In 811 the Doge's residence was moved to Rialto . This shift came at a time when Byzantium and the Frankish Empire were fighting under Charlemagne over the legal successor to the Roman emperors . This contrast led to the formation of parties and power struggles within the city, to which some Doges also fell victim. At the same time, the most powerful families strived for sole rule with the help of the Doge's office, whereas the other families allied themselves. In this way they prevented the formation of a dynasty and the core of Venice's complicated constitution took shape. All male adults of the noble families had a seat and vote on the Grand Council . At the same time, supervisory bodies with almost unlimited powers, such as the Council of Ten or the Senate, were of considerable importance. The most powerful families dominated politics and profitable long-distance trade. Skilful traversing between the great powers brought Venice favorable trade agreements, which earned it an almost monopoly in trade between Western Europe and Byzantium. At the same time it developed its relations with the Muslim rulers early on.

In 828 the bones of the Evangelist Mark were stolen from Alexandria . In his honor and a worthy place for its relics which originated St. Mark's Basilica . The two columns on the piazzetta bear the figure of St. Theodore and the winged lion , the symbol for the evangelist Mark, who ousted Theodore as patron saint. The lion of St. Mark became the coat of arms and emblem of Venice, omnipresent both in the city and in all areas ruled by Venice .

An important source of the lagoon city's wealth was the salt monopoly, which was of the utmost importance for the preservation of meat and fish. Venice also played a decisive role in the import of the staple food grain, so that the supply of northern Italy depended on its storage facilities until the early modern period - a frequently used means of political blackmail. Important goods and luxury goods from Asia and Africa such as silk , furs , ivory , spices, dyes and perfumes were transshipped via the Levantine and North African ports. In return, trade in goods from Western and Northern Europe was carried out via Venice - such as gold , silver , amber , wool, wood, tin and iron , but also cut jewels, glassware, medicines and slaves. In order to safeguard maritime trade, Venice built a shipyard, the Arsenal , from 1104 , which was expanded several times. The fleets built here accompanied the regular merchant convoys and were at the same time a means of curbing piracy and expanding the colonial empire, initially in the Adriatic. As early as the 8th century, Venice made itself increasingly independent from Byzantium, even if the Byzantine fleet lay in Venice several times from 806 to 810 to defend the city against the Franks. In 815 the two empires formally recognized each other. Venice also followed Constantinople's request in 828 to provide support against the Arabs off Sicily , again about two years later. Emperor Lothar I endowed Venice with numerous rights in 840, which amounted to a confirmation of its independence. Other sovereign treaties with the kings of Italy followed, such as 888 with Berengar I , 891 with Wido of Spoleto , 924 with Rudolf of Burgundy and 927 with Hugo I of Provence . At the beginning of the 10th century Venice appears for the last time as part of the Byzantine Empire in a Byzantine source. Between 842 and 846, however, the Slavs advanced as far as Caorle , and 875 the Saracens as far as Grado; Attacks by the Hungarians, who penetrated the lagoon in 900, forced Venice to surround the islands of Rialto with walls, and a chain protected the entrance to the Grand Canal.

Rise to great power

The policy of Emperor Otto II broke with the tradition of his predecessors, which had existed since 812, of respecting Venice's affiliation with Byzantium. As a result, the pro-Ottonian Dog dynasty of the Candiano was overthrown in 976, and a fire destroyed the Doge's Palace. When the Coloprini family, still loyal to Otto, got into an open dispute with the pro-Byzantine Morosini and Orseolo, they turned to Emperor Otto for help. From 981 he responded with trade blockades, but he died in 983, so that the possibly imminent submission to the empire did not take place. Now there was a rapprochement between the two empires. In 992 Venice received a first trading privilege from the Byzantine emperor Basil I , the Roman-German ruler Otto III. took over the sponsorship of the doge's son in 996. His fleet enforced the political supremacy of Venice as far as Ragusa . Venice had become a great power under Doge Pietro II Orseolo , but the dynastic policies of his successors brought them into conflict with both empires in the 1020s. Between 1132 and 1148, the dominance of the Doge was contrasted with a council body from which the Grand Council developed. Representatives of the noble families had a seat and vote in it.

In the high and late Middle Ages, Venice's social order was closely linked to the division of labor. The nobility was responsible for politics and high administration as well as for warfare and naval management. The Cittadini, the bourgeois merchants, provided funds and added value through trade and production, the Popolani, the majority of the population, provided soldiers and sailors, were responsible for all forms of manual labor and ran the retail trade. At the end of this development, the long-established nobility ensured that the Great Council was sealed off from newly rising families (Serrata, from 1297) and the older forms of popular participation in power were disempowered. Although the Serrata was only one stage in the increasing isolation of the Venetian oligarchy, it is undisputed that “at the end of the 13th century and in the first half of the fourteenth there was a class division between nobles who were politically active and the rest of the people”.

Outwardly, the Normans, who established themselves in southern Italy, threatened the supremacy of Venice in the Adriatic. At the same time, Byzantium lost large parts of Anatolia when Turkish groups built up dominions from the 1050s and increasingly from the 1080s. Venice supported the near collapse empire by keeping the Normans in check, who were also trying to conquer Constantinople. For this, Venice received a far-reaching trade privilege from Byzantium in 1082. During the course of the first crusades , Venice often supported the crusaders with its fleet, and the Doge was even offered the royal crown of Jerusalem. Venice forced Byzantium to renew the trade privilege of 1082, which now increasingly endangered the economic independence of the empire.

Under Manuel I , the hostilities between Venetians and Byzantines in Constantinople increased until the Venetians had to leave the capital in 1171. At the same time, Byzantium approached Hungary, which made Venice controversial for control of the Adriatic. Friedrich Barbarossa expanded the field of conflict when he got involved in Italian politics. Venice allied against him in 1167 with the Lega Lombarda , a northern Italian city federation, which was supported by the Pope. Even with the Normans of southern Italy, Venice was now in league, while Frederick fought the Italian ambitions of the Byzantine emperor, who temporarily controlled Ancona on the Adriatic. In 1177, Frederick I and Pope Alexander III agreed . a peace treaty in Venice.

Fourth crusade, conflict with Genoa, uprisings

The Doge Enrico Dandolo directed the Fourth Crusade in 1202, first to Zadar , whose uprising was suppressed, and then to Constantinople, which was conquered in 1204. Countless art treasures found their way to the West in this way, including the bronze quadriga of St. Mark's Church. In addition, Venice expanded its colonial empire to include numerous bases, above all Crete , which, however, defended itself in a chain of uprisings against the settlers that Venice brought to the island. However, this “coup” also resulted in an ongoing conflict with Genoa , which was the cause of four devastating wars. In 1261 the Greeks regained control of Constantinople, where they now played off their Genoese allies against Venice. Venice, for its part, allied itself with Charles of Anjou, who had conquered southern Italy in order to retake Constantinople. It was not until 1285 that Venetians were allowed to trade in the Byzantine capital again. In 1310 a nobility revolt led by Baiamonte Tiepolo shook the republic, in 1355 the Doge Marino Falier attempted a coup and from 1363 to 1366 the Venetian settlers on Crete revolted against Venice's rigid policies. In 1379, in alliance with Hungary, the Genoese managed to conquer Chioggia for a year, but the Peace of Turin (August 8, 1381) heralded a new phase of prosperity, especially since Genoa, weakened by internal struggles, no longer represented a great danger. In contrast, another danger did not let the city rest for three centuries. The plague of 1348 caused the population of Venice to collapse from around 120,000 to perhaps 60,000. From April 1348 the numerous dead were brought to two islands, San Leonardo Fossamala and San Marco in Bocca Lama . This wave of plagues was followed by another 25 epidemics into the early 16th century. In 1423, the Lazzaretto Vecchio was the first plague hospital.

In the years from 1402 Venice brought large parts of northern Italy and Dalmatia under its control (→ Terraferma ). Venice challenged the King of Hungary and the Empire Sigismund of Luxembourg in two places, because Aquileja, threatened by Venice, was an imperial fief and, as King of Hungary, Sigismund had a claim to the cities of Dalmatia. A first war from 1411 to 1413 was followed by a second from 1418 to 1420, but Venice prevailed at the end of 1433.

Metropolis between the world powers

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Venice had to gradually cede its positions in the eastern Mediterranean to the Ottomans . At the same time, it waged several wars against Milan, and from 1494 France and the Holy Roman Empire intervened militarily in Italy. Venice had conquered the so-called Terraferma - especially from 1405 - and ruled over Veneto , Friuli and a large part of Lombardy at the end of the 15th century . The reasons for the expansion of power to the mainland were the competition of the Ottomans, the growing importance of trade routes through the Po valley and across the Alps to Central and Northern Europe, and the possibility of producing food on their own estates. North of the Alps, the Nuremberg Stock Exchange was an important trading center for goods from Venice. It served as a link to other European economic centers such as Lyon and Antwerp . Nuremberg merchants used the Fondaco dei Tedeschi as a trading office in Venice . Conversely, Venetian merchants settled in Nuremberg. This included the wholesale merchant Bartholomäus Viatis . With perhaps 180,000 inhabitants, Venice almost reached its highest population after 1550, with around two million people living in its colonial empire. In 1509 Venice suffered a heavy defeat against a confederation of states. Emperor Maximilian I reclaimed the Terra Ferma as an alienated imperial territory, Spain the recently occupied Apulian cities, the King of France Cremona , the King of Hungary Dalmatia. There followed changing coalitions in which Venice was able to assert itself.

Reformation and Counter-Reformation

The Roman Catholic Patriarchate of Venice, established in 1451, had conflicted relations with the Roman Curia again and again. Traders, merchants, craftsmen, intellectuals and clergy from all over the world lived in Venice and promoted a more cosmopolitan and humanistic climate. Around 500 publishers and printers worked here in the 16th century. From 1520 the writings of the German reformer Martin Luther spread in Venice and then throughout Italy. It was not until 1524 that reading or possession of Protestant literature was punished with excommunication from the Catholic Church. The forbidden books were now passed on in secret and discussed among open-minded people in private homes. Small evangelical denominations emerged, but they hardly appeared in public.

The Franciscan Bartolomeo Fonzi (1502–1562) preached Luther's ideas about the Reformation, and the German traders in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi were particularly keen listeners. In 1531 he fled to Augsburg and stayed there for three years, where he translated Luther's well-known text from 1520 "To the Christian nobility of the German nation from improving the Christian status" into Italian. In 1534 he returned to Venice, increasingly feeling drawn to the more radical Anabaptist groups .

In 2016 Venice was awarded the honorary title “ City of the Reformation of Europe ” by the Community of Evangelical Churches in Europe .

As part of the Counter Reformation , the Inquisition was established in 1542 . Many people oriented towards the Reformation then left Venice and fled mainly to Zurich , Basel , Strasbourg and Geneva . In 1550 the Anabaptists held a synod in Venice, but soon after they were discovered and persecuted by the Inquisition. Fonzi was also captured in 1558, condemned as a heretic after four years, and drowned in the lagoon. All Protestant circles were destroyed by 1600. Only in the Palazzo Fondaco dei Tedeschi were German traders and merchants allowed to celebrate a closed German-language Protestant church service under strict conditions.

Decline, class order

Venice's importance declined more and more as a result of the shift in world trade to the Atlantic . The monopoly on the spice trade with the Levant was finally lost in the course of the 17th century. The sea battle of Lepanto , in which Venice succeeded for the last time in playing a role between the world powers of the Spaniards and Ottomans and providing the largest fleet, is considered to be the turning point . The loss of Cyprus (renunciation in 1573) was followed by further losses, until Crete was also lost in 1669.

In its foreign policy, the republic relied on diplomacy and an efficient information system. Pragmatism, precise arithmetic and rationality were usually the basis of political action. They stayed out of the ideological and religious disputes as much as possible. Venice had neither permanent problems with Muslims nor with Jews; rather, people knew how to ensure their benefits. At most there were problems with the Pope because of the striving for political supremacy and the territorial policy of the Curia .

No other city in Europe has made such decisive use of its class structure for the division of labor as Venice. The nobility took care of politics, high administration, as well as warfare and naval management. The bourgeois merchants (around 3 to 4 percent of the population) provided funds, added value through trade and the production of luxury goods. The majority of the population provided soldiers and sailors and did manual labor. In the era of the rise, the aristocratic families were involved in the economy and administration of the city: They traded, managed offices, commanded galleys and fleets and were involved in the numerous bodies of the state in the - temporary - offices, the costs of which they bore themselves and which they filled out without any special training.

From the late 16th century onwards, competitors from Northwestern and Western Europe developed superior credit and trading techniques. Their economic policy also took on strongly protectionist features. Now the luxury industry (especially glass production ) took over the role of the declining Levant trade, as did tourism. Venice was able to keep Dalmatia and temporarily the Peloponnese under its sovereignty, but in 1718 the Peloponnese was finally lost. The economic decline of the city in the 17th and 18th centuries is more likely to be interpreted as a falling back against the faster growing competitors than as a shrinking process. Nevertheless, it was possible to expand the existing defenses in the lagoon between 1744 and 1782.

Belonging to France and Austria, struggle for independence (1848–1849)

In 1797 the aristocratic republic dissolved and was occupied by the French under Napoleon Bonaparte , then annexed to Austria from 1798 to 1805 . After it had been part of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy from 1805 to 1814 , it came back to Austria in 1814 and 1815 as part of the Lombardy-Venetian Kingdom . In 1830 the city received a free port and in 1845 it was tied to the mainland by the Bridge of Freedom (Ponte della libertà).

In the revolutionary year of 1848, the Repubblica di San Marco was proclaimed under Daniele Manin on March 23 , which was able to maintain its independence against the Austrian besiegers for over a year. On August 22, 1849, the city, which was additionally affected by the cholera , had to capitulate, and on August 27, Austrian troops marched in. The state of siege was not lifted until 1854. During this time the Motta di Sant'Antonio fortress was demolished.

Proclamation of the Repubblica di San Marco on March 23, 1848 (lithograph by Nicola Sanesi, approx. 1850)

Rudolf von Alt : St. Mark's Square with the Austrian Army (around 1860), painting in the Army History Museum

"Daniele Manin e Nicolò Tommaseo liberati dal carcere e portati in trionfo in Piazza San Marco" ('Daniele Manin and Nicolò Tommaseo freed from prison and brought to St. Mark's Square in triumph'; painting by Napoleone Nani (1841–1899), approx. 1876, Fondazione Querini Stampalia)

Kingdom of Italy

As a result of Austria's defeat by Prussia in the war of 1866 , in which the newly founded Kingdom of Italy was an ally of Prussia in 1861 , Venice became part of Italy in accordance with the Treaty of Vienna on October 3, 1866. Giobatta Giustinian , who had opposed Austrian rule, became the first mayor . The first glass-blowing factories emerged, especially Salviati & C. Under his successor Giuseppe Giovanelli (1868–1875), plans arose to build the Strada Nova, a wide street in Cannaregio. In the decades that followed, cultural organizations were developed and numerous palaces were bought up by the municipality and modernized the port facilities.

During the 19th century, Venice was discovered by numerous German artists, including Friedrich Nerly , Ernst Oppler , Paul von Ravenstein , Gustav Schönleber and Max Liebermann .

Industrialization, tourism, World War I

Social stagnation and long economic decline occurred throughout northern Italy. By 1890, 1.4 million people had emigrated from the Veneto alone. Mayor Dante Di Serego Alighieri (1879–1881 and 1883–1888) pushed through the motorization of public shipping by introducing the vaporetti . But it was not until Mayor Riccardo Selvatico (1890–1895) that there was increased industrialization and the construction of new and affordable apartments. His successor Filippo Grimani (1895-1919) continued these efforts as the leader of a conservative government, with the municipal area of the commune being expanded. The driving force behind these changes was the so-called " Gruppo veneziano ", to which Giuseppe Volpi and Vittorio Cini belonged. In 1917 the port of Marghera was opened, which strengthened the division of labor between the industrial edge of the lagoon and the old town, which mainly focused on tourism. During the First World War, Austro-Hungarian planes attacked Venice from the air more than forty times.

Fascism, World War II, annihilation of the Jewish community

The fascists tried, in conjunction with the Gruppo veneziano, to make Venice an industrial metropolis. Alongside Genoa, it was to become the most important port in Italy. To do this, they extended the city's borders to the mainland (Greater Venice). From 1926 the industrial complex Mestre-Marghera belonged to Venice, three years later a car bridge with a parking garage was built ( Piazzale Roma ), a train station and artificial islands like Tronchetto . No consideration was given to local building traditions. The mayors no longer carried the official title Sindaco , but again the medieval title Podestà ; they were no longer elected, but appointed. With the fall of Mussolini , the German Reich took power in Venice, with the National Socialists having the remaining members of the Jewish community deported to the extermination camps.

Post-war coalitions, dispute over the lagoon and mainland industry

The resistance fighter Giovanni Ponti was mayor from 1945 to 1946, followed by the communist and partisan Giobatta Gianquinto until 1951. This was followed by a series of center-right governments, which were replaced by socialist ones in the mid-1970s. Until well into the 1970s, industrial policy took precedence, so that the lagoon became a sewer, which was exposed to more and more devastating floods due to the widened passages to the Adriatic Sea and the destruction of the ecological balance , such as in 1966. At the same time, the population decreased in the Old town to under 60,000, its obsolescence increased.

Under Mayor Massimo Cacciari (1993–2000 and 2005–2010) the government subsidized the restoration of the houses, developed flood protection projects, had all sewers cleaned and tried to move European institutions to Venice. The expansion of the university also contributed to the rejuvenation of the population.

population

language

In the Veneto , but also in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region , in Trentino and in Istria , a language of its own is spoken in addition to Italian, which is known as Venetic . Since March 28, 2007 it has been recognized as a language - at least by the Veneto Regional Council. An important variety of this language is venesiàn (Venetian) spoken in Venice . Venetian is one of the Western Romanic languages and differs greatly from standard Italian in terms of pronunciation, sentence formation and vocabulary. It was also the language of the Republic of Venice .

population

Around 1300 the Venice of the lagoon alone probably had around 85,000 to 100,000 inhabitants, a number that rose rapidly and possibly reached 140,000 before the first plague wave of 1348. Around 1600 one can reckon with around 150,000 to 160,000 inhabitants, but the 200,000 mark has probably never been exceeded.

The Italian city initially shrank, but recovered in the course of industrialization, from which the historic center also initially benefited. In the meantime, around one in three Venetians lives in the lagoon, only one in four in the center.

|

|

|

On the mainland, the Terraferma, the city counted 179,794 in 2019, in the Centro Storico 52,996, in the lagoon (Estuario) 27,730 inhabitants, a total of 260,520. The proportion of women is 136,432, that of men 124,088.

The inhabitants were distributed among the Municipalità and its Quartieri as follows:

| Population by district | |||||||

| Municipalità | Quarters | Residents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favaro Veneto | Favaro Campalto | 23,852 | |||||

| Mestre Carpenedo | Carpenedo Bissuola | 38.006 | |||||

| Mestre Carpenedo | Mestre Centro | 50,473 | |||||

| Chirignago Zelarino | Cipressina Zelarino Trivignano | 15,122 | |||||

| Chirignago Zelarino | Chirignago Gazzera | 23,824 | |||||

| Marghera | Marghera Catene Malcontenta | 28,517 | |||||

| Venezia Murano Burano | S.Marco, Castello, S.Elena, Cannaregio | 31,655 | |||||

| Venezia Murano Burano | Dorsoduro, S.Polo, S.Croce, Giudecca | 21,341 | |||||

| Venezia Murano Burano | Murano S.Erasmo | 4901 | |||||

| Venezia Murano Burano | Burano Mazzorbo Torcello | 2644 | |||||

| Lido Pellestrina | Lido Alberoni Malamocco | 16,474 | |||||

| Lido Pellestrina | Pellestrina S. Pietro in Volta | 3711 | |||||

Age structure and population decline

The proportion of under 18-year-olds is between 12 and 14 percent in most quarters, although the proportion in the quarters of the lagoon, including the old town, is not significantly lower, contrary to what appears to be. However, the proportion of at least 65-year-olds, who make up almost 30 percent of the local population, is noticeably higher. However, here too the proportion on the mainland is only slightly lower (by 27 percent). But while the population on the mainland is growing again, albeit very slowly, the lagoon is losing around 1 percent of its population every year.

Immigration

As of December 31, 2010, 29,281 people were expected to be foreign nationals, of which 4,373 lived in the historic center, 1,323 in the lagoon area and 23,585 on the mainland. Africans made up a total of 1929 immigrants. Immigration from Asia is considerably higher, especially from Bangladesh with 4740, then China (2163), the Philippines (1212), Sri Lanka (590) and Pakistan (189) as well as India (116). A total of 9,862 people came from Asia. In contrast, only 1,109 immigrants came from America, of which 282 came from Brazil, 170 from the USA, 136 from Peru, 117 from the Dominican Republic, 114 from Cuba. The largest groups came from Eastern and Southeastern Europe: Moldova (4565), Ukraine (2242), Romania (3315) and Albania (1455) as well as Macedonia (1419). A total of 16,347 immigrants came from European countries including the EU, the rest came from Australia and Oceania (21) or were of unknown nationality (13).

Religions

The Venetians are predominantly Catholic, their head is the Patriarch of Venice , who has had this title since 1457. Francesco Moraglia has been the incumbent since 2012 . In his official area, the Archdiocese of Venice, 348,922 of the 376,399 inhabitants, or 92.7%, were Catholic.

As early as 1520 there were a growing number of supporters of the German reformer Martin Luther in Venice , because his writings were also printed and distributed here. At the time of the Counter Reformation , with the introduction of the Inquisition in 1542, the Evangelicals were persecuted, driven out and drowned. Only in the Palazzo Fondaco dei Tedeschi of the German traders and merchants was the celebration of German-speaking Protestant services tolerated. In 2017 there was a Lutheran , a Waldensian Methodist , an Anglican , a Baptist , an Adventist church, Pentecostal churches and other Christian special groups in Venice.

The important Jewish community was largely destroyed by the National Socialists. It now consists of around 500 members again, most of whom live in the ghetto , the city district whose name was later transferred to all ghettos . They have lived there since 1516.

It is difficult to pin down the Muslim community, which consists of North Africans and Bengalis and which so far has no official mosque. You probably have more than three thousand members.

politics

Mayors and political bodies

The mayor or sindaco are supported by eleven assessors who together form the Giunta comunale, the city government. The city council (Consiglio comunale) has 40 councilors, each elected for five years (most recently in 2010), whose task is the control of the government. The council, in turn, has eleven permanent commissions that collect and process information and create templates. The venue is the Ca 'Loredan in the San Marco sestiere . The incumbent from April 2010 until his resignation due to corruption allegations in June 2014 in connection with the MO.SE lock project was Giorgio Orsoni . From July 2, 2014, Venice was provisionally ruled by Vittorio Zappalorto , Prefect of the Province of Gorizia . On June 14, 2015, Luigi Brugnaro was elected mayor of the city.

Each municipalità in turn has a kind of district council (Consiglio di Municipalità). Chirignago-Zelarino has 18 councilors, Venezia Murano Burano 29, Mestre Carpenedo 29, Favaro Veneto 25, Marghera 18 and Lido Pellestrina 18.

Special features of the conflict lines

On the one hand, the political lines of conflict reflect the social contradictions and party conflicts. In addition, there is the contrast between the needs of the lagoon locations and those of the mainland. Environmental and financial policy are increasingly in the foreground at the local level. The necessary maintenance and renovation measures, but above all the flood protection, which alone devours around 650 million euros, threaten to bring the city to the brink of insolvency against the background of the global economic crisis.

Town twinning

Venice has partnerships or cooperation agreements with the following cities and institutions. The year of establishment in brackets. Partnerships

-

Dubrovnik , Croatia (2012)

Dubrovnik , Croatia (2012) -

Istanbul , Turkey (1993)

Istanbul , Turkey (1993) -

Sarajevo , Bosnia and Herzegovina (1994)

Sarajevo , Bosnia and Herzegovina (1994) -

Suzhou , China (1980)

Suzhou , China (1980) -

Tallinn , Estonia

Tallinn , Estonia

-

Yerevan , Armenia (2011)

Yerevan , Armenia (2011) -

Saint Petersburg , Russian Federation (2013)

Saint Petersburg , Russian Federation (2013)

Cooperation agreement

-

L'Associazione Centrale dei Comuni e delle Comunità della Grecia (KEDKE), Greece (2000)

L'Associazione Centrale dei Comuni e delle Comunità della Grecia (KEDKE), Greece (2000) -

Nuremberg , Germany (1999)

Nuremberg , Germany (1999) -

Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2001)

Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2001) -

Qingdao , China (2001)

Qingdao , China (2001) -

Thessaloniki , Greece (2003)

Thessaloniki , Greece (2003)

The partnership between Venice and Nuremberg was concluded in 1954. On September 25, 1999, on this basis, it was only decided between Venice and Nuremberg to “re-establish their friendly relations”.

economy

The economic structure is divided into two parts. While the mainland is characterized by industrial structures, the area of the lagoon is heavily influenced by tourism, trade and the construction industry. Numerous small businesses determine the picture, up to the most common form, the one-person company, as they are usually portrayed by the gondoliers. At the end of 2015, there were 24,699 independent economic enterprises in the province of Venice in trade alone, almost 19,243 in handicrafts, 10,200 in tourism, and construction and transport based on more than 12,075 and over 4,100 units respectively. There were also service companies. In total, the economic area of the province of Venice had approx. 89,000 companies, of which only 8,347 were in agriculture and fishing (see Valle da pesca ). Since 2009, the number of companies has decreased from 91,000 to 89,000 at the end of 2015.

Agriculture and fishing

As early as 2001, only around 760 people were still working in lagunar agriculture, but they use it to supply the old town markets with food, mainly from S. Erasmo . The situation is completely different on the mainland part of the city, especially south and west of the coastal industrial belt.

Only 366 sole proprietorships are still working in the field of marine animal capture. On the one hand, mussel fishing plays an important role, on the other hand, fishing and breeding. In the lagoon this happens in the Valle da pesca , fish cultures delimited by reeds, rows of stakes or dams, which cover a total of 92 km² of the 550 km² lagoon.

Glass industry

Glass has been produced in the Venice area since late antiquity, but the boom in handicrafts only began with the complete relocation of the glass furnaces to Murano at the end of the 13th century. Angelo Barovier succeeded in discoloring glass in the middle of the 15th century. The Crystallo, a soda-lime glass decolorized with manganese oxide, became the leader in Europe. The artistry in this area was almost unrivaled until around 1600, and even after that, glass à la façon de Venise was considered unsurpassed in the German-speaking world. Baroque chopped glass did not break the priority of Venice until the 18th century.

The establishment of a glass school on Murano (1860) and the founding of a company by Antonio Salviati (1866) consciously followed on from the art tradition with its thin-walled wing glasses, thread and net glasses (reticella) . The Fratelli-Toso glass vessels of the 1950s and 1960s represent the Art Nouveau style in Millefiori decors, and their color and decor are based on Expressionism ; colorful stripes and geometric Op Art decors in vetro pezzato technique are typical of the designs by Paolo Venini , Fulvio Bianconi and Ercole Barovier. His son Angelo Barovier sometimes refers to Vasarely .

The Murano glass industry is still important among the manufacturing trades. The Consorzio Promovetro Murano, which promotes glass companies, lists 66 companies here alone, the oldest of which is Pauly & C. - Compagnia Venezia Murano , which Salviati co-founded and which has existed since 1866.

Industrial companies, port city of Marghera

Larger companies exist mainly on the mainland part of the city, where companies in the chemical and oil industries, shipbuilding and the two airports are the largest employers. Most of the population lives there.

For this purpose, land was expropriated on a large scale in the years before and after the First World War, and the emerging communities were merged with the cities of the lagoon to form the city of Venice. In 1933 the bridge from the mainland to the old town was expanded, the train station and parking lot along with artificial islands were created, and the passages into the Adriatic were widened and deepened. Mestre had only 9,950 inhabitants in 1881 and 35,860 in 1931. Metal processing, chemical and shipbuilding companies have settled in the port of Marghera. Between the Stazione Marittima and the port, the wide and deep Canale Vittorio Emanuele II was built in 1922, and in the following year the Canale Nord and the oil port, and finally the Canale Brentello.

After the Second World War, companies like Montedison or EniChem Agricoltura (until 1994), which produced fertilizers and pesticides, or shipbuilders like Fincantieri settled in Marghera . In Mestre, petrochemicals and the port dominated, and numerous workers moved from the old town to the mainland. In 1939 there were 15,000 employees here, and 20 years later there were already 35,000. In 1963 the city already had over 200,000 inhabitants. With the expansion of the motorway towards Pavia , a stronger economic connection to the mainland was achieved, but the shipbuilding and chemical industries fell into a serious crisis in the 1960s. In 1999 Mestre had only 180,000 inhabitants and only 28% of the jobs were offered by industry and 71% by the service sectors.

Between 1995 and 2005 the annual economic growth was 3%. But between 2008 and 2009 industrial production collapsed by 19.5%, in the neighboring province of Padua even by 27.9%. In 2014, 456,000 TEU containers were handled in the port , and it is also the starting point for RoRo ferries to Greece and cruise ships .

tourism

Tourism is by far dominant for one of the most visited cities in Europe, in which every third person who spends a year is a tourist. Venice attracted around 30 million visitors in 2011, three times as many as Rome; In 2007 it was only 21 million. The previous number of overnight stays of 11 million has apparently been declining for years due to the sharp rise in prices. In 2010 there were more than 8.5 million overnight stays compared to more than 8.8 million overnight stays in 2007. However, the number of overnight guests increased slightly from 2007 to 2011 - from 3.6 million in 2007 to 3.7 million a year 2010 - the average length of stay, namely 2.4 days in 2007, fell slightly to 2.3 days in 2010, which led to an overall decrease in the number of overnight stays. More visitors stayed overnight in Venice for a shorter time than before. In 2011 more than a million visitors came to the carnival alone, bringing in a total of 40 million euros for the city.

While the historic Venetian Carnival ended abruptly in 1797, this lost tradition was revived for tourism in the 1980s, transforming the traditionally weak February occupancy into an additional high season that is important for occupancy. The carnival bobbed away both under the Austrians and after the annexation to Italy in 1866. In 1914, the patriarch Aristide Cavallari warned of the sinfulness of tango in time for the carnival. In 1924, the fascist city government banned the wearing of masks during Carnival, only to finally ban it in 1933. Such attempts regularly failed, however, only in 1979 the opportunity was seen to expand the carnival primarily under the aspect of tourism promotion.

In 1999, the flow of tourists led to an unusual action by the city administration: posters warned of Venice. This action was directed against day tourists, who bring little in the city besides stress. This poster campaign by Oliviero Toscani warned of the ugly side of Venice with drastic photos of rats, polluted canals and decaying palaces in order to deter those visitors who were expecting a postcard idyll. In 2015, Mayor Brugnaro considered restricting access to St. Mark's Square and special access for locals to the clogged vaporetti. Because while mass tourism, and especially day and cruise tourism, continues to increase, the number of inhabitants of the lagoon city is falling continuously (2015: 56,300 inhabitants), second home ownership is increasing sharply, local supply is collapsing and quality tourism is reporting vacancies. 2012, this issue was in the film The Venice principle of Andreas Pichler discussed. One speaks of overtourism , under the motto #EnjoyRespectVenezia, one urges tourists not to sit on the floor, and many other things and lists fines of up to 500 euros.

At the beginning of 2019, the city administration, led by Mayor Brugnaro, presented a concept with which day tourists should also make a contribution to the costs they incur, such as urban waste disposal, which annually burdens the city's citizens with 30 million euros. This concept provided for the gradual introduction of an entrance fee for day tourists from May 2019, but was postponed to July 2020 due to problems with the establishment of the sales outlets. The plan is to have an entrance fee that is staggered depending on the number of visitors, ranging from 3 to 10 euros at peak times. From 2022, booking in advance will also be mandatory for day trippers.

traffic

While the traffic on the mainland part of the city corresponds to that of a medium-sized city, it is organized completely differently in the lagoon part. Water and pedestrian traffic predominate here.

Handcarts

In the inner-city area, loads are transported by land using handcarts ( carrelli ). Due to the many bridges, these have a special shape. The load rests mainly on the main axle, the front support wheels are used to push the cart over the depth of the next higher steps until the wheels of the main axis can be placed on the previous, lower steps.

Water transport

Gondolas

The most famous means of transport in Venice is the gondola , which is mainly used for tourism. The traghetti (gondola ferries) are an exception. They cross the Grand Canal in eight places and bring their passengers, mostly standing, from one side of the bank to the other. This shuttle service is one of the obligations of every gondolier and is performed in turn. It dates from the times when only the Rialto Bridge crossed the canal. In order to limit the lavish splendor in the construction of the gondolas, the Senate, or a facility to combat waste (Provveditori sopra le pompe) ordered in 1562 that the gondolas had to be uniformly black. Their length was limited to almost 11 m, their width to 1.75 m, their weight to 700 kg. In 2012, for example, gondolas were 1.4 m wide and weighed a little more than half. At that time 10,000 gondolas are said to have existed, now there are perhaps 3000 again, even if hardly more than 400 licenses were issued. The predominant type of gondola was developed by the boat builder Domenico Tramontin, his oldest surviving boat dates from 1890. There are at least three shipyards that also build gondolas.

The gondola family includes the Barchéta da traghetto, Disdotona (driven by 12 rowers), Gondolin (a small gondola), Gondolon (a large one), Balotina and Mussin (with a forward-sloping bow, otherwise similar to the gondolin ). They are all connected by an asymmetrical design. The boats lean slightly to the right to compensate for the pressure of the rudder on the right with steering to the left and the weight of the gondolier on the left. The Gondolino da regata is only driven during the Regata storica , a regatta through the Grand Canal. There are also a large number of traditional watercraft.

Motor boats

There are several hundred private motor boats in Venice, but their waves endanger the substance of the houses. There are also around 200 water taxis and other hotel boats. In August 1995, the gondola drivers blocked the Grand Canal to protest against the high waves of the motorboats. The screws of the ship's engines also enrich the water with oxygen and thus contribute to the formation of putrefactive bacteria that decompose the wooden foundations. In November 2001 the Italian government declared Venice a state of emergency. In addition to private boats, there are public ones, such as those used by the police and fire brigade, but also municipal garbage disposal.

Police (Polizia), fire brigade ( Vigili del Fuoco ) and various hospitals and their ambulances maintain their own boat fleets, similar to garbage disposal and the post office. When it comes to the police, a distinction must be made between the state police ( Polizia di Stato ), the Carabinieri and the Guardia di Finanza . There are also the Coast Guard ( Guardia Costiera ), the Polizia locale , provinciale and lagunare.

Vaporetti

Water buses ( vaporetti ) were introduced from 1881 against the resistance of the gondoliers who blocked the Grand Canal with a chain and who protested again in 1887. The municipal transport company ACTV (Azienda Consorzio Trasporti Veneziano) is responsible for its operation . These ships have a very shallow hull, which reduces their draft . So the house facades should be spared, against which the waves slosh with enormous forces. This is one of the reasons why strict speed limits apply in Venice and no vaporetto is allowed to turn in the Grand Canal. The vaporetti also travel to the neighboring islands and the mainland in a dense network of routes.

tram

Since 2010 a new tram has been running between the endpoints in Mestre and Piazzale Roma in the historic old town (T1). A special feature is that this tram runs according to the Translohr system without conventional rails; For this purpose, a rail recessed into the ground is used for track guidance in the vehicle center line. See Venice tram .

railroad

There are two important train stations in Venice, namely Venezia Santa Lucia as the terminus in the historic center and the Venezia Mestre junction in the mainland district of the same name. To the west of it is a disused marshalling yard , which is still used for local freight traffic . Around 82,000 travelers arrive in Santa Lucia every day, with around 450 trains running, a total of 30 million passengers per year. The architect Angiolo Mazzoni suggested the construction in 1924 . Ten years later, a competition was announced, which Virgilio Vallot won. In 1936 it was agreed that Mazzoni - Vallot should carry out the construction, the completion of which was interrupted in 1943. After the war, Paolo Perilli brought it to an end.

Mestre train station, which opened in 1842, has slightly higher passenger numbers. Around 500 trains run here every day.

Under Mayor Paolo Costa (2000-2005) the creation of a subway line with direct exit on St. Mark's Square and Murano was pushed. Costa's predecessor and successor in office, the philosopher Massimo Cacciari , as well as his other successors, however, did not give the project any priority, further plans are not known.

A funicular built by Doppelmayr , the People Mover , runs between the island of Tronchetto and Piazzale Roma . In addition to the two head stops, the line, which is built on an average of seven meter high stilts, also serves the ferry port via the Marittima stop . The 822 meter long route is covered in three minutes.

Airports

Venice has three airports: Venice Marco Polo Airport, Treviso Airport , which is served by some low-cost airlines, and a small landing pad for private planes on the Lido. In 2006, the Marco Polo handled 7.7 million passengers; in the first nine months of 2008 there were already 6,786,000. This makes the airport the fourth largest in Italy after Rome and the two near Milan. However, the number of passengers fell slightly in 2008, but Treviso Airport increased by 10%. Together, the airports form the third largest complex in Italy.

Ferry and cruise port

Venice is the starting point for RoRo ferries to Greece and the destination of numerous cruise ships . These ships usually used the Giudecca Canal with the touristic voyage past St. Mark's Square and docked at the harbor in the west of the old town near the train station. This route has been forbidden since the beginning of 2014 because the constantly growing ships with their waves are particularly endangering the buildings. Instead, a new ferry terminal in Fusina on the mainland with four berths was built with EU funds. From November 2014, cruise ships over 40,000 t were to be banned completely from the lagoon. In March 2014, however, the Venice Administrative Court declared the decision to be unlawful as there were no alternative routes available. The ferry connections have been using the new Fusina ferry terminal since June 2014.

Environment, lagoon, gardens

Given the special circumstances of Venice, environmental issues are more related to the lagoon. The most urgent problem is the increasingly frequent flooding of the city, but also the destruction of the lagoon itself, which is inextricably linked with it. The urban areas on the mainland are also very densely built up, but there are parks such as the Parco Alfredo Albanese or the Parco di San Giuliano in Mestre, which are 33 and 74 hectares in size. In addition, there is the Querini forest with around 200 hectares. The Republic of Venice had specifically protected such forests in order to secure high trees and wood supplies. However, they fell victim to industrialization and agriculture after 1797. Venice's old town has numerous private gardens, the majority of which are walled, most of which are not open to the public. This relies on the Giardini Papadopoli , the Biennale site and the Giardini Reali , the garden that Napoleon had laid out around 1810 between the New Procuraties and the basin of San Marco.

Flood

The city is often affected by floods ( acqua alta ) . On November 4, 1966, the highest flood recorded so far occurred, a storm surge with a height of 194 cm above normal level. On December 1, 2008, a flood reached 156 cm. On November 12, 2019, shortly before midnight, the level rose to 187 cm above sea level . Gusts of wind put some vaporetti and other boats ashore. "St. Mark's Basilica has only been flooded with similar severity five times in its history since the 9th century." In the Fenice Theater there was water ingress, the power supply and the fire alarm system failed.

The sea level in the lagoon was 23 cm higher in 2012 than it was around 1900, partly because of the lowering of the land at that time due to the now stopped water abstraction and partly due to the general rise in sea level. Since the end of 2004 is on MO.SE project ( mo dulo s perimentale e lettromeccanico) built. It consists of 78 lock gates on the sea floor that can be erected using compressed air. At the beginning of October 2020, the system was used for the first time as an actual protection of Venice during a flood with a forecast height of 130 cm.

Critics argue against the project that the sea level could rise even further due to global warming and the ecology in the lagoon city could be adversely affected by the locks. Indeed, a major problem is the ever-deepening port entrances to meet the needs of the oil industry (Porto Marghera industrial port) and tourism (cruise ships).

Water supply

Rainwater used to be collected in cisterns and wells, the pozzi; In 1322 alone, the Senate ordered the construction of 50 such cisterns. In 1858 there were well over 6,000 Pozzi, but only a fraction of them were open to the public. In addition, water was brought in barrels from rivers, such as from the Brenta. The water was transported by the guild of the Acquaroli, who brought drinking water to the city with their wooden boats, the burchi , when there was not enough of it.

The republic frequently arranged for the drilling of artesian wells . In 1848, the company entrusted with the search for water decided to drill a hole on Riva Ca 'di Dio. When they came across a layer of fresh water after 145 m, they were so euphoric that they continued drilling. However, this damaged the sealing reservoir of the freshwater found and made it unusable.

At the suggestion of the London company Ritterbant & Dalgairns to lay a water line from the Seriola into the city (1875), the river from Moranzani to the Brenta near Strà was extended so that it also carried the water of this river. In 1885 the water pipeline was put into operation. Ritterbant & Dalgairns then drew up a further plan and a contract was signed in 1889, which was fulfilled in 1891 with the commissioning of a new, sublagunar pipeline. In 1897 Murano, in 1900 the Giudecca, the Lido and other small islands were connected to the aqueduct. On July 18, 1911, however, a ship tore open the main pipe of the water pipe and within a very short time all of the drinking water was rendered unusable by the brackish water that had penetrated . Extensive repair and cleaning work did not remove the damage sufficiently, so that work on the construction of a new water pipeline began in 1912. It was completed after the end of the war. The line ran over a length of more than 20 km from Sant'Ambrogio ( Scorzè ) to S. Giuliano on the edge of the lagoon. A double pipe, partly at the bottom of the lagoon, supplied Venice with sufficient drinking water from the Sant'Ambrogio springs.

After the Second World War , not least due to the demands of increasing mass tourism, new sources were constantly tapped and water pipes laid on the mainland.

Mussel fishing