Otto III. (HRR)

Otto III. (* June or July 980 in the Reichswald near Kessel (Ketil) near Kleve ; † January 23 or 24, 1002 in Castel Paterno near Faleria , Italy) from the House of Ottonians was Roman-German king from 983 and emperor from 996 .

At the age of three he was elected German king. During his immaturity, the empire was administered by the empresses Theophanu and Adelheid of Burgundy . During his reign, the focus of rule shifted to Italy. His reign is shaped by very individual decisions. So Otto used his own candidates against the rebellious Roman city nobility with his confidante Bruno of Carinthia as Pope Gregor V and Gerbert von Aurillac as Pope Silvester II . In Poland a church organization independent of the Reich was set up. In 1001 Otto had to flee Rome after an uprising. Otto's early death ruined the attempt to recapture. His body was buried in Aachen's Marienkirche , today's cathedral.

For a long time he was considered an “un-German” emperor. Based on the research of Percy Ernst Schramm , who mainly influenced Otto III's Italian policy. included in the long-term concept of the Renovatio imperii Romanorum (renewal of the Roman Empire), recent research discusses whether far-reaching political conceptions can be ascribed to his rule.

Life until the assumption of power

Insecure beginnings

Otto III's parents were Emperor Otto II and his Byzantine wife Theophanu . He was born in 980 on the journey from Aachen to Nijmegen in the Ketil Forest. With Adelheid , Sophia and Mathilde he had three sisters.

In July 982 his father's army was defeated by the Saracens in the battle of Cape Colonna . The emperor found it difficult to escape. At the urging of the princes, at Pentecost 983 a court conference was called in Verona , the most important decision of which was the election of Otto III as king. was. At the same time it was the only royal election carried out on Italian soil. Otto III traveled with the departing participants of the court day. across the Alps to receive the royal consecration at the traditional coronation site of the Ottonians, in Aachen. When he was crowned king there on Christmas 983 by the archbishops Willigis of Mainz and Johannes von Ravenna , his father had been dead for three weeks. Shortly after the coronation celebrations, the news of his death arrived and "put an end to the joyous festival," as Thietmar von said Merseburg reports.

The death of Otto II led to revolts against Ottonian rulers both in Italy and in the east of the empire . East of the Elbe, a Slav uprising in 983 ruined the success of Christian missionary policy. This precarious situation caused numerous bishops, who were among the greats of the empire, to shrink from the prolonged reign of a minor.

Struggle to succeed Otto II.

As a member of the Bavarian line, Heinrich der Zänker was the closest male relative. Heinrich, who was imprisoned in Utrecht for several rebellions in the 970s against Otto II, was released by Bishop Folcmar of Utrecht immediately after Otto's death . Archbishop Warin of Cologne handed over to him the very young king who had just been crowned according to kinship law ( ius propinquitatis ). There was no contradiction to this, since in addition to Otto's mother Theophanu, his grandmother Adelheid and his aunt Mathilde were still in Italy.

The brawler strove for the takeover of the royal rule, less for the guardianship of the child. A formulation in Gerbert von Aurillac's letter book led to considerations as to whether Heinrich should not act as co-regent according to the Byzantine model. Otherwise, there are hardly any other sources for a concept of co-regency. Heinrich tried to build networks through friendship and oaths. He immediately arranged a meeting in Breisach with the aim of making an alliance of friendship with the West Frankish King Lothar , who was related to the young Otto in the same degree as he was. For unexplained reasons, however, Heinrich shied away from meeting Lothar and immediately moved from Cologne, where he had taken on young Otto, via Corvey to Saxony . In Saxony, Heinrich invited all the greats to Magdeburg to celebrate Palm Sunday . There he campaigned openly for support for his kingship, but with little success. Nevertheless, his following was large enough to move to Quedlinburg and celebrate Easter there, consciously following the Ottonian tradition. Heinrich tried to obtain the consent of those present for a king's insurrection in negotiations and managed to get many to "swear their support as their king and master". Those who supported Heinrich included Mieszko I of Poland, Boleslaw II of Bohemia, and the Slav prince Mistui .

In order to thwart Heinrich's plans, his opponents left Quedlinburg and formed an oath ( coniuratio ) on the Asselburg . When Heinrich learned of this, he and military units moved from Quedlinburg to Werla to be close to his opponents, either to break them up or to make agreements with them. He also sent Bishop Folcmar of Utrecht to them to negotiate a solution to the problem. It became clear that Heinrich's opponents were not ready "to give up the loyalty they had sworn to their king". Heinrich only received an assurance for future peace negotiations in Seesen . Thereupon he left abruptly for Bavaria; there he found the recognition of all bishops and some counts. After his failures in Saxony and successes in Bavaria, everything now depended on the decision in Franconia. The Franconian greats under the leadership of the Archbishop of Mainz Willigis and the Swabian Duke Konrad were under no circumstances willing to question Otto's succession to the throne. Since Heinrich shied away from the military conflict, he handed the royal child over to his mother and grandmother on June 29, 984 in Rohr, Thuringia .

Reign of the Empresses (985-994)

Otto's mother Theophanu ruled from 985 until her death. The long period of her reign remained largely free of open conflicts. During her reign she tried to restore the diocese of Merseburg , which her husband Otto II had abolished in 981. Furthermore, she took over the chaplains of her husband's court orchestra , and their leadership also remained in the hands of the chancellor, Bishop Hildebold von Worms and the arch chaplain Willigis von Mainz. Both bishops almost became co-regents of the empress through regular interventions.

In 986 the five year old Otto III celebrated. the Easter festival in Quedlinburg. The four dukes Heinrich the Quarrel as truchess , Konrad von Schwaben as chamberlain , Heinrich the Younger of Carinthia as cupbearer and Bernhard of Saxony as marshal exercised the court offices there. This service of the dukes had already been exercised during the rise of Otto the Great in Aachen in 936 or that of Otto II in 961. Through this service the dukes symbolized their willingness to serve the king. In addition, the service of Henry the Quarrel at the place of his usurpation , which had failed two years earlier, symbolized his complete submission to royal grace. Otto III. received from Count Hoico and from Bernward , who later became Bishop of Hildesheim, extensive training in courtly and knightly abilities as well as intellectual education and upbringing.

During the reign of Theophanus, the Gandersheim dispute broke out over the question of whether Gandersheim belonged to the Hildesheim or Mainz diocese , from which the rights of the respective bishops were derived. This dispute came to a head when his sister Sophia did not want the responsible Hildesheim bishop Osdag to dress herself as a sanctimoniale and instead turned to the Archbishop of Mainz, Willigis. The threatened escalation of the dispute was in the presence of King Otto III. and his imperial mother Theophanu avoided for the time being that both bishops should take over the ceremony, while the other Sanctimonial von Osdag had to dress alone.

During the months of the throne dispute with Heinrich the Quarrel on the eastern border, things remained quiet, but the Liutizen uprising resulted in massive setbacks for the Ottonian missionary policy. Therefore, Saxon armies carried out campaigns against the Elbe Slavs in 985, 986 and 987. According to recent research, the decisive motive for the fighting was less the mere recapture of the lost territories, but the urge for revenge, the greed for prey or tribute. Six-year-old Otto accompanied the Slavs' procession of 986, who was the first to take part in an act of war. The Polish Duke Mieszko supported the Saxons several times with a large army and paid homage to Otto, where he is said to have honored him in 986 with the gift of a camel. In September 991 Otto advanced against Brandenburg, which could be captured for a short time. In 992, however, he suffered heavy losses when the Slavs moved again off Brandenburg. At the time of the fighting on the eastern border, theophanu postulated an eastern political concept that was supposed to have deliberately prepared Poland's church independence. Instead of Magdeburg, she made the Memleben monastery the headquarters of missionary policy and thus consciously opposed Magdeburg's claims that aimed at sovereignty over the missionary areas. However, such considerations have largely been made without any source.

In 989 Theophanu went on a trip to Italy without her son with the primary goal of praying for his soul's salvation on the day of her husband's death. In Pavia she handed over the central administration to her confidante Johannes Philagathos , whom she had made Archbishop of Piacenza . In Italy Theophanu issued some documents in his own name, in one case her name was even given in the masculine form: Theophanis gratia divina imperator augustus. However, the few available sources hardly reveal any contours of the content of an Italian policy. One year after her return from Italy, Theophanu died on June 15, 991 in the presence of her son in Nijmegen and was buried in the St. Pantaleon monastery in Cologne. What Theophanus' last advice or instructions were for the young ruler is not recorded. A memorial foundation Theophanus for Otto II., The execution of which she commissioned the Essen abbess Mathilde , was only after 999 by Otto III after the transfer of the relics of Saint Marsus . realized. Later the king spared no effort for the salvation of his mother's soul. In his documents he speaks of his "beloved mother", and he made many donations to the Cologne monastery.

For the final years of Otto's minority, his grandmother Adelheid took over the reign, still supported by the Quedlinburg Abbess Mathilde. Ottonian coinage reached its peak during her reign. But Theophanus' policy did not find continuation in everything. While she wanted to reverse the abolition of the diocese of Merseburg, Adelheid was not ready to do so.

Assumption of power

The transition to independent government did not take place in a demonstrative act or on a specific date, but through the gradual loss of reign of the imperial women. In research there is the opinion, often expressed, that Otto III. had at the supposed Reichstag of Sohlingen in September 994 obtained full governance in the form of a sword line . In Otto's case, the sources do not contain any references to such an act of military detention or guiding the sword, which would have marked the end of the reign and the beginning of independent rule. A document dated July 6, 994, in which Otto gave the Eschwege estate to his sister Sophia , was interpreted by Johannes Laudage as the beginning of independent government. However, Otto notarized a large number of donations - also for his sister - when he was still a minor.

Otto made the first independent decisions as early as 994 and, together with his confidante Heribert, installed a German as Chancellor of Italy - in a position that until then had only been reserved for Italians. In Regensburg in the same year Otto put his chaplain Gebhard on the bishop's seat instead of the Regensburg cleric Tagino, who was elected by the cathedral chapter .

In the summer of 995 he held a court day in Quedlinburg and from mid-August to the beginning of October continued the trains against the Elbe Slavs living in the north, which have taken place almost annually since the Slav uprising of 983. The Mecklenburg was not taken as the most important castle of the Obodrites , as is often assumed , but Otto stayed in Mecklenburg as a friend and patron of the Obodrite Duke. After his return he expanded the diocese of Meißen considerably with a privilege issued in Frankfurt on December 6, 995 and multiplied its tithe income .

In September 995 were for a courtship Otto III. Archbishop Johannes Philagathos and Bishop Bernward of Würzburg were sent to Byzantium. The negotiations with Byzantium were successfully concluded shortly before Otto's death. Which princess he was promised is unknown.

Emperor Otto III.

The first Italian train

It was not only the desired imperial coronation that prompted King Otto III. for an imminent move to Italy, but also a cry for help from Pope John XV. who was harassed by the Roman city prefect Crescentius and his party and had to leave Rome. In March 996 Otto set out from Regensburg on his first train to Italy. In Verona he took over the sponsorship of a son of the Venetian doge Pietro II. Orseolo , Ottone Orseolo , who would later also become a doge from 1009 to 1026. In doing so, he continued the traditionally good relationship between the Ottonians and the Doges.

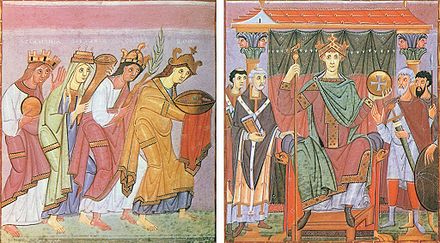

A Roman embassy met Otto in Pavia to discuss the successor to the now deceased Pope John XV. to negotiate. While still in Ravenna , he nominated his relative and court chaplain Brun of Carinthia as successor to the Pope and had Archbishop Willigis of Mainz and Bishop Hildebold accompany him to Rome, where he was the first "German" to be promoted to Pope and took the name Gregor V. Just one day after his arrival in Rome, Otto was solemnly overtaken by the city's senate and nobility and on May 21, 996, on the feast of Christ's Ascension , he was crowned emperor by “his” Pope.

With this decision, Otto III. the scope of action of his grandfather Otto I, in that he was no longer content with agreeing to elect a pope, but instead directed it specifically towards his own candidate. Due to this personnel decision, however, the Pope no longer had any support in Rome and he was all the more dependent on the help of the emperor. Ever since Otto I, there had been constant conflicts between popes loyal to the emperor and candidates from urban Roman aristocratic groups. The leading Roman noble family of the Crescentier owed its rise to the earlier popes loyal to Rome. It was based on the assignment of papal rights and the associated income in the Sabina .

The coronation celebrations, which lasted several days, were followed by a synod , during which the close cooperation between emperor and pope was evident in the joint chairmanship of the synod and in the issuing of documents. The coronation synod brought Otto III. also in contact with two important people who would have a strong influence on his future life. On the one hand with Gerbert von Aurillac , the archbishop of Reims, who already had such close contact with the emperor during this time that he wrote several letters on his behalf, on the other hand with Adalbert von Prague , a representative of the ascetic-hermitic piety movement that had grown stronger. Otto and Gerbert von Aurillac parted ways for the time being, but a few months later Gerbert received the imperial invitation to take up the service of the ruler: he was supposed to be Otto III as a teacher. help to achieve a Greek subtilitas (delicacy) in place of the Saxon rusticitas (rawness) .

The Roman city prefect Crescentius was by Otto III. Condemned to exile, but pardoned on the intercession of Pope Gregory V. So Otto III occupied himself. the clementia (mildness), which was a central part of the Ottonian rule.

After the imperial coronation Otto moved back to the Reich in early June 996. He stayed from December 996 to April 997 on the Lower Rhine and above all in Aachen. Concrete decisions during this time, such as the holding of court days, are not known.

The second Italian train

At the end of September 996, only a few months after his pardon, Crescentius expelled Pope Gregory V from Rome and set up an antipope with the Archbishop of Piacenza and former confidante of Theophanu, Johannes Philagathos . Before Otto III. However, when he intervened in Roman conditions, he gave priority to securing the Saxon border and in the summer of 997 led a campaign against the Elbe Slavs .

In December 997 Otto began his second Italian train. The size of his army is unknown, but he was accompanied by a large number of worldly and spiritual greats. His dilectissima soror (beloved sister) Sophia, who had accompanied him on the first Italian train and had stayed with him during his long stay in Aachen, was no longer there. Her presence at court was never mentioned again. During his second journey to Italy, Otto entrusted the abbess Mathilde von Quedlinburg with his deputy in the empire, a position that until then had only been held by dukes or archbishops.

When Otto appeared in Rome in February 998, the Romans came to an amicable agreement with him and let him march peacefully into Rome. The leaders of the Romans, who did not want to make themselves dependent on the noble family of the Crescentians, are not mentioned by name in the sources. Meanwhile, the city prefect Crescentius holed up in the Castel Sant'Angelo . The antipope Johannes Philagathos fled Rome and hid in a fortified tower. He was captured and blinded by a detachment of the Ottonian army, and his nose and tongue were mutilated. Finally, a synod deposed him.

After an intense siege, the imperial army was able to get hold of Crescentius and beheaded him. The corpse was overthrown from the battlements of Castel Sant'Angelo, then hung by the legs on Monte Mario with twelve companions who were also executed and put on display.

Even contemporaries criticized the cruel behavior of the emperor and pope. So the aged abbot Nilus set out on the news of the mutilation of the antipope to Rome to bring Johannes Philagathos to his monastery, which Gregory V and Otto III gave him. however refused. Nilus is said to have threatened the emperor with the eternal punishment of God and left Rome. Yet Crescentius had already received forgiveness and grace once. According to the "rules of the game of medieval conflict management", the party that broke a peace treaty had to reckon with particular severity.

In a certificate from Otto of April 28, 998, which was issued for the Einsiedeln monastery and which drew attention to the execution of Crescentius in the date line, a lead bull appeared for the first time with the motto Renovatio imperii Romanorum (renewal of the Roman Empire). The new motto appeared on the imperial documents until the time of Otto III's return. from Gniezno and was replaced from January 1001 by the formulation Aurea Roma .

Stay in Italy 997–999

During the period of several years in Italy, the emperor and the pope tried to reform the church. Alienated church property should be returned to the control of the spiritual institutions. This goal also served their actions against a relative of Crescentius, a Count of Sabina named Benedikt, whom they personally forced with an army to return stolen property to the Farfa monastery .

Otto had an imperial palace built on the Palatine Hill . During his stay in Italy, the emperor from Rome also took part in several personnel decisions and occupied important episcopal seats with close confidants.

After the death of Halberstadt Bishop Hildeward in November 996, who was one of the masterminds behind the abolition of the diocese of Merseburg, Otto III. and Pope Gregory V in 997 reopened the procedure for the renewal of the diocese of Merseburg and justified this procedure at the Roman synod at the turn of the year 998/99 with the fact that the dissolution of the diocese in 981 had violated church law. The diocese was dissolved sine concilio (without a resolution). But it was only Otto's successor, Heinrich II , who had the diocese of Merseburg re-established in 1004.

At the beginning of 999 Otto found time for another penitential pilgrimage to Benevento on Monte Gargano, which is said to have been imposed on him by the hermit Romuald as atonement for his offense against Crescentius and Johannes Philagathos. On the way there, Otto learned that Gregor V had died in Rome after a short illness. During this time he also went to Nilus von Rossano as a penitent pilgrim.

After his return, he and his confidante Gerbert von Aurillac raised a non-Roman to pope again on New Year's Eve II. The emperor was also active in other personnel decisions from Rome and occupied important episcopal seats with close confidants. So he raised his chaplain Leo to Bishop of Vercelli and gave him a problematic diocese, since his predecessor Peter von Vercelli had been murdered by the Marquis Arduin of Ivrea . Arduin was sentenced to church penance in 999 before a Roman synod. The count was ordered to lay down his arms and not spend two nights in the same place if his health permitted. As an alternative to this penance, he was given free entry to the monk's class. It is not known whether the margrave fulfilled the conditions of the church penance. Even after the death of Bishop Everger of Cologne, Otto and his Chancellor Heribert appointed a person he trusted in this important bishopric.

Activities in the east

In February / March 1000 Otto made a pilgrimage from Rome to Gniezno , mainly for religious reasons: Thietmar reports that he wanted to pray at the grave of his confidante Adalbert. Bishop Adalbert of Prague was slain on April 23, 997 by pagan princes. Hagiographic texts emphasize that Otto came to Gniezno to get hold of Adalbert's relics.

On arrival in Gniezno, the focus was initially on religious motifs. Otto let himself be escorted barefoot by the responsible local bishop Unger von Posen to Adalbert's grave and with tears in prayer asked the martyr to mediate with Christ. Subsequently, the city was raised to the status of an archbishopric, which established the independent church organization in Poland. The newly established ecclesiastical province of Gniezno was assigned the existing diocese of Krakow and the new dioceses of Kolberg and Breslau to be founded as suffragans . The domain of Boleslaw Chrobrys was thus granted church-political independence.

Otto's further actions in Gniezno are controversial. The history of Poland by the so-called Gallus Anonymus , which was not written until the 12th century, gives a detailed account of the events . The entire portrayal of Gallus was intended to underscore the importance of Boleslaw's power and wealth. She reported in great detail that Otto III. Boleslaw made king, which the Saxon sources do not deliver. The process of a king's elevation is controversial in modern research. The thesis of Johannes Fried (1989) that in Gnesen there was a king's elevation limited to the secular act, Gerd Althoff (1996) opposed that Boleslaw in Gnesen with the putting on of the crown in a particularly honorable way as amicus within the framework of a friendship alliance of Otto III. had been awarded. The acts of handing over gifts mentioned by Gallus and the demonstrative unity through a feast lasting several days were common in early medieval amicitiae .

On the way back to the empire Boleslaw gave the emperor a splendid escort and accompanied the emperor via Magdeburg to Aachen. Otto is said to have given him the throne chair of Charlemagne there.

Return to Rome

Despite Otto's long absence, there were no major disputes in the Reich. His stay in the northern part of the empire only lasted a few months. Otto celebrated Palm Sunday and Easter in Quedlinburg in Magdeburg. Via Trebur he went on to Aachen, the place he “loved most next to Rome”, as it is called in the Quedlinburg annals . During these months in Magdeburg, Quedlinburg and Aachen, he addressed the re-establishment of the Merseburg diocese at synodal assemblies without coming to a decision. In Aachen, he distinguished some churches with the Adalbert relics. There he looked for and opened the tomb of Charlemagne. Even contemporaries criticized this act as a grave crime for which God punished the emperor with his early death. Otto's approach has recently been interpreted as a preparation for the canonization of Charlemagne. Ernst-Dieter Hehl also assessed the preparations for the canonization as part of a plan to set up a diocese in Aachen.

Otto moved from Aachen back to Rome in the summer of 1000. During this time, the Gandersheim dispute broke out again between Bishops Willigis of Mainz and Bishop Bernward, when the occasion of the consecration made a decision inevitable as to which of the two bishops was now responsible for Gandersheim. Bishop Bernward used the time to travel to Rome and let Otto III give his point of view. and confirm a Roman synod. As a result of Bernward's trip, two synods on the Gandersheim question met almost simultaneously: a regional one in Gandersheim and a general one in Rome, chaired by the emperor and pope. But neither this nor a subsequent synod in Pöhlde could resolve the dispute. It later employed the emperors Heinrich II and Konrad II and several synods before it was finally dissolved in 1030.

The emperor stayed in Italy throughout the second half of the year without any notable ruling activity. This only became necessary at the beginning of 1001, when the residents of Tivoli revolted against the imperial rule. Otto then besieged Tivoli, but the Vita Bernwardi , an eulogy by Thangmar on his student Bishop Bernward, emphasizes Bernward's influence on the subjugation of the residents. In the same month as the siege of Tivoli, an unusual legal act falls, namely the issuing of an imperial deed of donation for Pope New Year's Eve. This relentlessly reckons with the previous policy of the popes, who have lost their own possessions due to carelessness and incompetence and have tried to acquire rights and obligations of the empire illegally. In relation to the papacy, Otto was careful to preserve the imperial priority. The territorial claims of the Roman Church derived from the Constantinian donation , even the donation itself or its reproduction by Johannes Diaconus , he rejected as "lying" and instead gave St. Peter from his own imperial power eight counties in the Italian Pentapolis .

The Romans revolted in the weeks around this document was issued. The too mild treatment of Tivoli was named as the cause of the uprising. The uprising was peacefully settled within a few days through negotiations. The Hildesheim cathedral dean Thangmar, who accompanied his bishop Bernward von Hildesheim to Rome in 1001, reproduced Otto's famous speech to the Romans in the context of the peace negotiations, in which Otto discussed his preference for Rome and the neglect of his ties to Saxony. Moved to tears by this speech, the Romans seized two men and cruelly beat them to show their willingness to give in and to make peace. Despite the gestures of peace, the distrust persisted. Advisors urged the emperor to evade the uncertain situation there and await military reinforcements outside Rome.

death

Therefore Otto III moved away. and Pope Silvester II from Rome and moved north towards Ravenna. In the following years Otto received embassies from Boleslaw Chrobry, agreed with a Hungarian embassy to set up a church province with the Archdiocese of Gran as the metropolis, and ensured that the new Archbishop Askericus raised Stephan of Hungary to king. In addition, Otto strengthened the friendly relations with Pietro II Orseolo , the Doge of Venice during this time ; he met with him secretly in Pomposa and Venice. Otto had already adopted his son as a godfather in 996, and in 1001 he gave birth to his daughter.

On the other hand, the hagiographic sources - the Romualds vita of Petrus Damiani and the vita of the five brothers of Brun von Querfurt - portrayed a mentally torn monarch during these months. Otto is said to have visited the hermit Romuald in Pereum during Lent 1001 and subjected himself to penance and fasting exercises there. The statements of these testimonies culminate in Otto's promise to leave the rule to someone better and to become a monk in Jerusalem. However, he wants to correct "the errors" ( errata ) of his government for another three years . What errors he meant was not said. Compared to other rulers of the early Middle Ages, the density of source statements about ascetic achievements and monastic inclinations of the emperor is in any case singular.

Towards the end of 1001 he and the contingents of some imperial bishops, who had arrived very hesitantly in Italy, approached Rome. But suddenly strong fever attacks set in and Otto III died in Paterno Castle, not far from Rome. on January 23 or 24, 1002. Several reports emphasize the calm, Christian death of the ruler. The author of the Vita Meinwerci assumed that Otto had been poisoned.

The emperor's death was initially kept secret until the company's own contingent were informed and contracted. Thereupon the army withdrew from Italy, constantly threatened by enemies, in order to fulfill Otto's will and to bury him in Aachen. When the funeral procession moved from Paterno via Lucca and Verona to Bavaria in February 1002 , Duke Heinrich , according to Thietmar, received the funeral procession in Polling and urged the bishops and nobles in talks and with promises to elect him king. However, none of the participants in the funeral procession supported a successor to Heinrich - with the exception of the Augsburg bishop. The reservations that the followers of Otto III. against Heinrich remained unknown in detail. At Otto's funeral on Easter 1002 in Aachen, those responsible repeated their rejection, although in their opinion Heinrich was unsuitable for the kingship for many reasons. While in Italy on February 15, 1002 Lombard greats in Pavia with Arduin from Ivrea an opponent of Otto III. elected as the Italian king, Henry II was only able to assert himself in lengthy negotiations and feuds.

effect

Measures after Otto's death

Already at the beginning of his kingship, Heinrich II issued decrees for the salvation of his predecessor, the "beloved cousin" and the "good emperor Otto, divine memory". He confirmed numerous documents and orders of Otto and, like Otto once, celebrated Palm Sunday 1003 in Magdeburg, at Otto I's grave, and Easter in Quedlinburg, at the graves of Heinrich I and his wife Mathilde . However, Heinrich made the German part of the empire his center of power again. So he took more than a decade before he drove the Italian rival king out of his rule.

The change of the bull inscription of Renovatio imperii Romanorum , as it was in the time of Otto III. was in use, at Renovatio regni Francorum , i.e. from the renewal of the Roman Empire to the renewal of the Frankish Empire , as it was now practiced by Henry II, was for a long time interpreted as the most serious turning point in a systematically pursued new ruler's policy. An investigation by Knut Görich showed that this was an overinterpretation . Accordingly, there are 23 bulls from Otto compared to only four bulls from Heinrich. The "Frankenbulle" was only used for a short time and only on current occasions, namely after the political implementation in the empire in January and February 1003. Apart from that, it was used next to the traditional wax seals and was soon abandoned.

A more obvious turning point, however, occurred in Henry II's policy towards the Polish ruler. Boleslaw Chobry was born in Gniezno in 1000 by Otto III. Elevated to brother and accomplice of the empire and friend and comrade of the Roman people ( fratrem et cooperatorem imperii constituit et populi Romani amicum et socium appelavit ), then politics under Heinrich turned into confrontation, which was based on the peace treaties of Posen 1005, Merseburg 1013 and Bautzen 1018 can be divided into three phases.

Contemporary judgments

The contemporaries who had to explain the early death of the emperor looked for the reasons for this with Otto himself, who must have aroused the wrath of God through sinful actions. In the judgment of his contemporaries, Otto's Italian policy in particular was judged extremely critically.

In the Quedlinburg annals , which are written entirely from the perspective of the Ottonian house monastery, more precisely of his royal abbesses, i.e. Otto III's aunt or sister, it is said that he preferred the Romans to other peoples because of his special affection. However, Otto's government was not criticized; almost the entire world mourns his death, which appears neither as a consequence of his own sins nor of others.

Thietmar von Merseburg , whose portrayal it was to point out the injustice of the abolition of the diocese of Merseburg, expressed disapproval of Otto's Italian policy. The emperor dined at a raised semicircular table in his palace - raised from his own, completely contrary to the local custom of the Frankish and Saxon kings. Thietmar expressed strong criticism of the establishment of the Archdiocese of Gniezno and the associated downsizing of the diocese of Bishop Unger of Posen. Just as relentless is his accusation against Otto III., That he had made the Polish Duke Boleslaw Chrobry from tributarius (person liable to pay tribute) to dominus (lord).

Brun von Querfurt later reproached the emperor for wanting to make Rome his permanent residence and despising his homeland. In Brun's report, which is characterized by the interest in hagiography, Rome symbolizes the overcoming of non-Christian religions by the Christian belief that with its pagan rulers the city has also lost its glorious secular position of power and since the donation of Constantine it has been the city of the apostles over which a secular ruler is not Right to exercise more. Thus the campaign of revenge against the apostle seat weighs so heavily for Brun as a sin that the early death of the emperor presented itself to him as the immediate punishment of the emperor. Nevertheless, Brun von Querfurt also praised the emperor's positive aspects such as his human warmth: "Although still a boy and erring in his behavior, he was a kind emperor, an imperator Augustus of incomparable humanity".

Similar criticism of Otto's Italian policy was expressed in the vita of Bishop Adalbero of Metz , written around 1015 . According to her, Otto stayed almost exclusively in Italy. For this reason, his empires and his homeland have completely fallen into disrepair.

Nevertheless, it was not long before Otto III. admired for his unusual education and obvious acumen, and was called "Wonder of the World" in both Germany and Italy.

The low distribution of the early sources (Brun von Querfurt, Annales Hildesheimenses , Thietmar von Merseburg) meant that the image of Emperor Otto III. was deformed beyond recognition in the course of the Middle Ages. The vacuum of sparse information has been filled by dramatic rumors and speculations (poisoning, failed marriage, revenge of a lover) since the 11th century.

Otto III. in research

It was above all the critical judgments of contemporaries from the leading circles that shaped the judgment of the historians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Wilhelm von Giesebrecht justified the long-time valid judgment on Otto III. in its history of the German Empire. Above all, he criticized the lack of national awareness and accused Otto of unrealistic fantasy. Furthermore, Otto had carelessly gambled away a great inheritance, chased fantasies and dreams and surrounded himself with intellectuals and foreigners. Giesebrecht shaped the conception of national romantic historians for decades.

After the turn of the century, factual objections were raised against this assessment. Here coined Percy Ernst Schramm with his 1929 published work emperor, Rome and Renovatio the image of the emperor still prevail. His reassessment was a rehabilitation in comparison to the classification of the “un-German” emperor as a religious, unworldly phantasy, as Schramm first tried to understand the emperor from the spiritual currents of his time. What was particularly new was the intellectual historical interpretation of Otto III's policy, according to which the Roman idea of renewal should have been the real political driving force of the emperor. As a central testimony to the Roman idea of renewal, Schramm referred to the introduction of the famous lead bull since 998 with the motto Renovatio imperii Romanorum .

In 1941, in his history of the Saxon imperial era, Robert Holtzmann followed up on Giesebrecht's assessment and concluded: “The state of Otto the Great crashed in its joints when Otto III. died. Had this emperor lived longer, his empire would have broken apart ”. After 1945, judgments about Otto in the sharpness of Holtzmann became rare.

In 1954, Mathilde Uhlirz supplemented Schramm's point of view insofar as she looked at the emperor's policy more from the aspect of the consolidation of rule in the southern part of the empire and thus Otto III. assumed the intention to consolidate the real power of the empire there. In contrast to Schramm, Uhlirz emphasized the aspect of cooperation between the emperor and the pope, the aim of which was primarily to win Poland and Hungary over to Christianity with Roman characteristics. In the period that followed, a combination of the positions of Schramm and Uhlirz prevailed, so that efforts to secure rule in the south as well as the restructuring of relations with Poland and Hungary were recognized as integral parts of Otto's policy. However, one tried unchanged the policy of Otto III. to explain from the profile of his personality.

In recent years Schramm's interpretation of the renovatio has been criticized several times. According to the much-discussed thesis of Knut Görich , the politics of Rome are less based on a return to antiquity than on the impetus of the monastic reform movement. The Italian policy and the moves to Rome could be explained more from the interest in securing the papacy and the restitution of alienated church property than from a Roman renewal program. The motto does not refer to a “program of rule”, but to a very direct political goal. In his biography of the emperor published in 1996, Gerd Althoff turned away from political conceptions in the Middle Ages and considered them to be anachronistic, since two important prerequisites for political concepts with the written form and the implementing institutions were missing in the medieval royal rule. According to Althoff, the specific contents of a program of rule can hardly ever be taken from the sources, but are based only on conclusions from traditional events, which are consistently also capable of simpler interpretation. Against the more recent tendencies in research, Heinrich Dormeier pleaded for the idea of a Renovatio-Imperii-Romanorum concept of the emperor to be retained . The discussion about the ruler's renovation policy is still ongoing.

In 2008 Gerd Althoff and Hagen Keller accentuated the peculiarity of the royal exercise of power in the 10th century, "which was based on the pillars of presence, consensus and representation and was thus able to guarantee the functioning of an order". In assessing the emperor, restraint was appropriate, "because he was not granted anything more than beginnings".

reception

From a Roman policy of renewal Otto III. speaks a contemporary poem in which the imperial advisor Leo von Vercelli praises the cooperation between the emperor and the pope. This poem begins, however, with an invocation of Christ, who may look to his Rome and renew it so that it may blossom under the reign of the third Otto.

Due to his quickly completed résumé and the dramatic events in his reign, a large number of literary testimonies from the 16th century on Otto III. as the title character. But little was of literary duration.

In the poem Lamentation of Emperor Otto the Third by August von Platen-Hallermünde from 1833, the emperor was belittled from a national perspective. Ricarda Huch measured Otto III in the work Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1934 . to Otto I .; in rejecting the younger, she followed Giesebrecht's assessment. But also the positive revaluation of Otto III's life. found its way into literature. Two historical novels about the Kaiser appeared after the Second World War. In 1949 Gertrud Bäumer stylized him as a "youth in a starry cloak" on the throne. In 1951, Henry Benrath tried to capture his personality in an even more subjective and empathic way. For him it was about the "spiritual and spiritual vision of a ruler's life".

swell

Documents and regesta works

- Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II. And Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Johann Friedrich Böhmer , Mathilde Uhlirz : Regesta Imperii II, 3. The regests of the empire under Otto III. Vienna et al. 1956.

Literary sources

- Georg Waitz (Ed.): Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separately in editi 8: Annales Hildesheimenses. Hanover 1878 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Annales Quedlinburgenses . In: Georg Heinrich Pertz u. a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 3: Annales, chronica et historiae aevi Saxonici. Hannover 1839, p. 22 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Bruno von Querfurt : Vita quinque fratrum eremitarum. In: Georg Waitz , Wilhelm Wattenbach u. a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 15.2: Supplementa tomorum I-XII, pars III. Supplementum tomi XIII pars II. Hannover 1888, p. 709 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version) Translated from Wilfried Hartmann (Hrsg.): German history in sources and representation. Vol. 1, Reclam, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-15-017001-X , pp. 202-204.

- The Quedlinburg yearbooks. Translated by Eduard Winkelmann (= historian of the German prehistory. Volume 36). Leipzig 1891.

- Hermann von Reichenau : Chronicon. In: Rudolf Buchner, Werner Trillmich (Hrsg.): Sources of the 9th and 10th centuries on the history of the Hamburg church and the empire (= Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Vol. 11). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1961. Latin text in Georg Waitz u. a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 13: Supplementa tomorum I-XII, pars I. Hannover 1881, p. 61 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Thietmar von Merseburg, chronicle . Retransmitted and explained by Werner Trillmich . With an addendum by Steffen Patzold . (= Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Vol. 9). 9th, bibliographically updated edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-24669-4 . Latin text in Robert Holtzmann (Hrsg.): Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, Nova series 9: The Chronicle of Bishop Thietmar von Merseburg and their Korveier revision (Thietmari Merseburgensis episcopi Chronicon) Berlin 1935 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Thangmar : Vita Bernwardi episcopi Hildesheimensis. In: Georg Heinrich Pertz u. a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 4: Annales, chronica et historiae aevi Carolini et Saxonici. Hannover 1841, pp. 754–782 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

literature

General representations

- Gerd Althoff : The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 3rd, revised edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-17-022443-8 .

- Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller : Late Antiquity to the End of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt - Handbook of German History . Volume 3). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-60003-2 .

- Helmut Beumann : The Ottonen (= Kohlhammer Urban pocket books. Volume 384). 5th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-17-016473-2 .

- Michael Borgolte (Ed.): Poland and Germany 1000 years ago. The Berlin conference on the "Gnesen Act" (= Europe in the Middle Ages. Treatises and contributions to historical comparative literature. Volume 5). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003749-0 . ( Review )

- Hagen Keller: Ottonian royal rule, organization and legitimation of royal power. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-534-15998-5 .

- Thilo Offergeld: Reges pueri. The royalty of minors in the early Middle Ages (= Monumenta Germaniae historica. Volume 50). Hahn, Hannover 2001, ISBN 3-7752-5450-1 ( review ).

- Timothy Reuter (Ed.): The New Cambridge Medieval History 3. c. 900-1024. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, ISBN 0-521-36447-7 .

- Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Eds.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? (= Medieval research. Volume 1). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1997, ISBN 3-7995-4251-5 ( digitized version ).

Biographies

- Gerd Althoff: Otto III. (= Design of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. ). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-89678-021-2 .

- Ekkehard Eickhoff : Theophanu and the King. Otto III. and his world. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-608-91798-5 .

- Ekkehard Eickhoff: Emperor Otto III. The first millennium and the development of Europe. 2nd Edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-608-94188-6 .

- Knut Görich : Otto III. Romanus Saxonicus et Italicus. Imperial Rome politics and Saxon historiography (= historical research. Volume 18). 2nd unchanged edition. Sigmaringen 1995, ISBN 978-3-7995-0467-6 .

- Percy Ernst Schramm : Emperor, Rome and Renovatio. Studies on the history of the Roman idea of renewal from the end of the Carolingian Empire to the investiture dispute. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1992 = Leipzig / Berlin 1929.

- Mathilde Uhlirz: Yearbooks of the German Empire under Otto II and Otto III. Volume 2. Otto III. 983-1002. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1954 ( digitized ; PDF; 43.0 MB).

Lexicons

- Gerd Althoff: Otto III. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Volume 25, Berlin / New York 1995, pp. 549-552.

- Knut Görich: Otto III. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 6, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-044-1 , Sp. 1352-1353.

- Knut Görich: Otto III. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , pp. 662-665 ( digitized version ).

- Tilman Struve : Otto III . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 6, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-7608-8906-9 , Sp. 1568-1570.

Web links

- Confirmation certificate from Otto III. of December 12, 993 to the Diocese of Würzburg

- Publications on Otto III. in the opac of the Regesta Imperii

Remarks

- ↑ Thilo Offergeld: Reges pueri. The royalty of minors in the early Middle Ages. Hanover 2001, p. 656.

- ↑ Thietmar III, 26.

- ↑ Thietmar III, 17-18.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III . Darmstadt 1996, p. 42.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens : ... more Grecorum conregnantem instituere vultis? On the legitimation of Heinrich the quarrel's reign in the throne dispute of 984. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 27 (1993), pp. 273-289.

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: Late antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt - Handbook of German History. Volume 3. 10., completely revised edition). Stuttgart 2008, p. 275.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Relatives, friends and faithful. On the political significance of group ties in the early Middle Ages. Darmstadt 1990, p. 119ff.

- ^ Like Otto II, Lothar and Heinrich der Zänker are direct grandsons of Heinrich I.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 1.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 2.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 4.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 9.

- ^ Thangmar, Vita Bernwardi, cap. 13.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 64; Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians, royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition. Stuttgart 2005, p. 160.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 37 (2003), pp. 99-139, here: p. 102 ( online )

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 9.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 37 (2003), pp. 99-139, here: p. 102 ( online ).

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 67.

- ↑ Diploma of the Theophanu in No. 2. In: MGH DD O III, 876f. See: Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: Late Antiquity to the End of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt - Handbook of German History. Volume 3. 10., completely revised edition). Stuttgart 2008, p. 284.

- ↑ Klaus Gereon Beuckers : The Essen Marsus shrine. Investigations into a lost masterpiece of the Ottonian goldsmith's art. Münster 2006, pp. 11f, 50ff.

- ^ Heiko Steuer: Life in Saxony at the time of the Ottonians. In: Matthias Puhle (Ed.): Otto the Great, Magdeburg and Europe. 2 volumes, Zabern, Mainz 2001, pp. 89–107, here: p. 106. (Catalog of the 27th exhibition of the Council of Europe and the State Exhibition of Saxony-Anhalt).

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: Late antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt - Handbook of German History. Volume 3. 10., completely revised edition). Stuttgart 2008, p. 287; Thilo Offergeld: Reges pueri. The royalty of minors in the early Middle Ages. Hanover 2001, p. 740.

- ↑ Thilo Offergeld: Reges pueri. The royalty of minors in the early Middle Ages. Hanover 2001, p. 734.

- ↑ Document No. 146 in Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II and Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hannover 1893, pp. 556–557 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Johannes Laudage: The problem of guardianship over Otto III. In: Anton von Euw / Peter Schreiner (ed.): Empress Theophanu: Encounter of the East and West at the turn of the first millennium, Cologne 1991, pp. 261–275, here: p. 274.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 73.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 79.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: King Otto III. and the Slavs on the Baltic Sea, Oder and Elbe around the year 995. Mecklenburgzug - Slavnikid massacre - Meißen privilege. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 37 (2003), pp. 99-139, here: pp. 106-113 ( online ).

- ↑ MGH DO.III. 186

- ↑ Bernward died on September 20, 996 on Euboea , before the embassy could reach Constantinople .

- ^ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians, royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition. Stuttgart 2005, p. 176.

- ^ Letter from Otto III. to Gerbert of Reims. Document No. 241 in Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II. And Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893, pp. 658–659 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ^ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians, royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition. Stuttgart 2005, p. 179.

- ↑ Steffen Patzold: Omnis anima potestatibus sublimioribus subdita sit. On the image of the ruler in the Aachen Otto Gospels. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 35 (2001), pp. 243–272, here: p. 243.

- ↑ Document No. 255 of October 1, 997, in Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II and Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893, pp. 670–672 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized )

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Gandersheim and Quedlinburg. Ottonian convents as centers of power and tradition. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 25 (1991), pp. 123-144, here: p. 133.

- ↑ Böhmer-Uhlirz, Regesta Imperii II, 3: The Regests of the Empire under Otto III., No. 1272a, p. 685f.

- ^ Vita S. Nili, cap. 91. In: Georg Heinrich Pertz u. a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 4: Annales, chronica et historiae aevi Carolini et Saxonici. Hanover 1841, pp. 616–618 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 105ff. See further examples in Gerd Althoff: Rules of the game of politics in the Middle Ages. Communication in peace and feud. Darmstadt 1997.

- ↑ Document No. 285, in Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II. And Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hannover 1893, p. 710 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version ); Original document of the monastery archive Einsiedeln (KAE 33) can be viewed on the document page : Documents (0947-1483) KAE, document no. 33 in the European document archive Monasterium.net .. The first illustration does not show the original, but a later copy with German registration.

- ↑ First used for MGH DO.III. 390 of January 23, 1001; but also MGH DO.III. 389 for Sylvester III. already carried the bull. Compare with Knut Görich: Otto III. Romanus Saxonicus et Italicus: Imperial Rome politics and Saxon historiography. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 267ff.

- ↑ MGH Constitutiones 1, ed. by Ludwig Weiland, Hanover 1893, No. 24, cap. 3, p. 51, digitized .

- ^ Mathilde Uhlirz: Year books Otto III. P. 292 and p. 534-537.

- ↑ On this event: Michael Borgolte (Ed.): Poland and Germany 1000 years ago. The Berlin conference on the "Gnesen Act". Berlin 2002.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 44.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians, royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition. Stuttgart 2005, p. 189.

- ^ Gallus Anonymus, Chronicae et gesta ducum sive principum Polonorum I, 6.

- ↑ Johannes Fried: Otto III. and Boleslaw. The dedication image of the Aachen Gospel, the "Act of Gniezno" and the early Polish and Hungarian royalty. An image analysis and its historical consequences. Wiesbaden 1989, pp. 123-125.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, pp. 144ff.

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: Late antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt - Handbook of German History. Volume 3. 10., completely revised edition). Stuttgart 2008, p. 315.

- ↑ Ademar 1, III.

- ↑ Annales Quedlinburgenses ad an. 1000.

- ^ Hagen Keller: The Ottonians and Charlemagne. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 34 (2000), pp. 112-131, here: pp. 125ff.

- ↑ Annales Hildesheimenses a. 1000.

- ↑ Knut Görich: Otto III. opens the Karlsgrab in Aachen. Reflections on the veneration of saints, canonization and the formation of traditions. In: Gerd Althoff / Ernst Schubert (ed.) Representation of the rulers in Ottonian Saxony, Sigmaringen 1998, pp. 381–430.

- ^ Ernst-Dieter Hehl: Rulers, Church and Canon Law in the Late Ttonian Empire. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Eds.), Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point ?, Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 169–203, here: pp. 191ff.

- ↑ Thangmar Vita Bernwardi, cap. 23.

- ↑ Document No. 389, in Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II. And Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893, pp. 818-820 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version) [Translated from] Wolfgang Lautemann (Hrsg.): Geschichte in Quellen 2, Munich 1970, pp. 205f.

- ^ Thangmar Vita Bernwardi, cap. 25th

- ↑ Knut Görich: Secret meeting of rulers: Emperor Otto III. visits Venice (1001). In: Romedio Schmitz-Esser, Knut Görich and Jochen Johrendt (eds.): Venice as a stage. Organization, staging and perception of visits to European rulers. Regensburg 2017, pp. 51–66.

- ↑ Petrus Damiani, Vita beati Romualdi, cap. 25; Brun von Querfurt, Vita quinque fratrum, cap. 2 and 3. Cf. Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 182.

- ↑ Steffen Patzold: Omnis anima potestatibus sublimioribus subdita sit. On the image of the ruler in the Aachen Otto Gospels. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 35 (2001), pp. 243–272, here: p. 271.

- ^ Thangmar, Vita Bernwardi, cap. 37; Brun von Querfurt, Vita quinque fratrum, cap. 7; Thietmar IV, 49.

- ↑ Vita Meinwerci, cap. 7th

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 50.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 54.

- ↑ DH II. 3: pro salute anime dilecti quondam nostri nepotis dive memorie boni Ottonis imperatoris.

- ↑ Annales Quedlinburgenses ad an. 1003

- ↑ Knut Görich: Otto III. Romanus Saxonicus et Italicus. Imperial Rome politics and Saxon historiography. Sigmaringen 1993, p. 270ff.

- ^ Gallus Anonymus, Chronica et gesta ducum sive principum Polonorum, ed.Karol Maleczyńsky, Monumenta Poloniae Historica NS 2, Krakau 1952, p. 20.

- ↑ In detail: Knut Görich: A turn in the east: Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. In: Bernd Schneidmüller and Stefan Weinfurter (Eds.): Otto III. and Heinrich II. - a turning point ?, Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 95–167.

- ↑ Annales Quedlinburgenses ad an. 1001f.

- ↑ Annales Quedlinburgenses ad an. 1002

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 47.

- ↑ Thietmar IV, 45.

- ↑ Thietmar V, 10.

- ^ Brun von Querfurt, Vita quinque fratrum, cap. 7th

- ^ Brun von Querfurt, Vita quinque fratrum, cap. 7th

- ^ Brun, Vita Adalberti c. 20, translation after Ekkehard Eickhoff: Kaiser Otto III. The first millennium and the development of Europe. 2nd Edition. Stuttgart 2000, p. 362.

- ↑ Constantinus, Vita Adalberonis II., Cap. 25th

- ↑ Annales Spirenses in Georg Heinrich Pertz u. a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 17: Annales aevi Suevici. Hannover 1861, p. 80 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version ); Chronica Pontificum et Imperatorem S. Bartholomaei in insula Romana in Oswald Holder-Egger (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 31: Annales et chronica Italica aevi Suevici. Hanover 1903, p. 215 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Rudolf Schieffer: About marriage, children and the murder of Emperor Otto III. An example of the dynamism of historical fantasy. In: Hubertus Seibert, Gertrud Thoma (ed.): From Saxony to Jerusalem. People and institutions through the ages. Festschrift for Wolfgang Giese on his 65th birthday. Munich 2004, p. 111–121, here: p. 120 ( online )

- ↑ See Wilhelm Giesebrecht: History of the German Empire. Vol. 1, pp. 719, 720f. and 759.

- ↑ On the history of research: Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 2ff.

- ↑ Robert Holtzmann: History of the Saxon Empire. Munich 1941, p. 381f.

- ^ Mathilde Uhlirz: Yearbooks of the German Empire under Otto II. And Otto III. Second volume: Otto III. 983-1002. Berlin 1954, pp. 414-422.

- ^ Mathilde Uhlirz: The becoming of the thought of the Renovatio imperii Romanorum in Otto III. In: Sent. cnet. it. 2 (Spoleto 1955) pp. 201-219, here: p. 210.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 11.

- ↑ Knut Görich: Otto III. Romanus Saxonicus et Italicus: Imperial Rome politics and Saxon historiography. Sigmaringen 1995, pp. 190ff .; P. 209ff. P. 240ff .; P. 267ff.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 31.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 115.

- ^ Heinrich Dormeier: The Renovatio Imperii Romanorum and the "foreign policy" of Otto III. and his advisors. In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Poland and Germany 1000 years ago. The Berlin conference on the "Gnesen Act" Berlin 2002, pp. 163–191.

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: Late antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt - Handbook of German History. Volume 3. 10., completely revised edition). Stuttgart 2008, p. 309.

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Gerd Althoff: Late antiquity to the end of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt - Handbook of German History. Volume 3. 10., completely revised edition). P. 315.

- ^ Matthias Pape: August from "Platens Lamentation of Emperor Otto the Third" (1834). Historical image and aesthetic content. In: Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch 44 (2003) pp. 147–172.

- ^ Ricarda Huch: Roman Empire of the German Nation. Berlin 1934, p. 66f.

- ↑ Gertrud Bäumer: The youth in the starry cloak. Greatness and tragedy of Otto III. Munich 1949.

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Otto III. Darmstadt 1996, p. 18.

- ^ Henry Benrath: The Emperor Otto III. Stuttgart 1951, p. 5.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Otto II. |

Roman-German King from 996 Emperor 983–1002 |

Henry II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Otto III. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Roman-German king and emperor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 980 or July 980 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Reichswald near Kleve |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 23, 1002 or January 24, 1002 |

| Place of death | Castel Paterno near Faleria , Italy |