Hagen Keller

Ruedi Hagen Keller (born May 2, 1937 in Freiburg im Breisgau ) is a German historian who researches the history of the early and high Middle Ages . Above all he works on the Ottonian age , the Italian urban communes and the culture of writing in the Middle Ages. Keller taught from 1982 until his retirement in 2002 as a professor for medieval history at the Westphalian Wilhelms University in Münster . There was a particularly fruitful collaboration with his colleague Gerd Althoff . With their work, Keller and Althoff made a decisive contribution to Münster's reputation in international mediaeval studies . Keller's research has exerted a considerable influence on German and international medieval studies since the 1980s and led to a reassessment of the early and high medieval royal rule.

Life

Origin and early years

Hagen Keller was born in Freiburg im Breisgau in May 1937 as the son of the independent businessman Dr. Rudolf Keller and his wife Ruth, b. Frankenbach. He has four siblings, including the volcanologist Jörg Keller . Italy was a particular attraction for the whole family. The family first traveled to Italy to Lake Maggiore in 1952 . From the 1950s, the father established business relationships in Italy. He imported Italian woodworking machines . Keller's younger brothers continued this line of business. Keller's younger sister was an au pair who taught German to the children of an Italian family. Jörg Keller temporarily went to Catania to study and later worked as a volcanologist with Italy.

After the bombing of Freiburg in 1944 , the family lived in Pfullendorf north of Lake Constance . In 1950 she returned to Freiburg. During his school days, Hagen Keller dealt intensively with astronomy. Since childhood he was less interested in historical novels or biographies, his historical curiosity was stimulated by monuments and concrete objects. The starting point for his historical awareness were the immediate experiences of his childhood, the Second World War and National Socialism .

In 1956, Keller graduated from the Kepler Gymnasium in Freiburg. Inspired by the upper school classes in mathematics and physics, he wanted to study these subjects first. However, he rejected this plan shortly before the beginning of the semester. Keller decided to become a teacher. From the 1956 summer semester to the 1962 summer semester, he studied history, Latin philology, scientific politics, German studies, philosophy and sports at the Universities of Freiburg and Kiel . He completed the medieval proseminar in the first semester with Manfred Hellmann . His interest in the Middle Ages was encouraged in his third semester in the summer of 1957 by Hans Blumenberg's lecture in Kiel on the philosophy of the 14th and 15th centuries . After his return to Freiburg, Keller concentrated on this era , especially with Gerd Tellenbach .

academic career

From the beginning of 1959, Keller was part of the “Freiburg Working Group” on medieval person research, a group of young researchers led by Gerd Tellenbach. There he got to know Karl Schmid , Joachim Wollasch , Eduard Hlawitschka , Hansmartin Schwarzmaier and Wilhelm Kurz . The professional exchange with Karl Schmid had a particularly long-lasting impact on him. As a student of Tellenbach, Keller initially dealt with basic questions of the Alemannic-Franconian history of the early Middle Ages. In 1962 he received his doctorate from Tellenbach on the subject of Einsiedeln Monastery in Ottonian Swabia .

In 1962/63, Keller was a research assistant at Tellenbach at the Institute for Historical Regional Studies at the University of Freiburg, then from 1963 to 1969 research assistant at the German Historical Institute in Rome. During his stay in Rome, Keller found one of his future focus areas in the social structure of Italy in the Middle Ages. In Italy, Keller also spent the first years of his marriage with Hanni Kahlert, whom he married in 1964.

From 1969 to 1972 Keller worked again as a research assistant at the History Department of the University of Freiburg. There he acquired 1972 with a thesis on seniors and vassals, capitans and valvassors. Investigations into the ruling class in the Lombard cities of the 9th – 12th centuries Century, with special attention to Milan, the teaching qualification for Medieval and Modern History. The habilitation thesis has been substantially revised and expanded for printing. He gave his inaugural lecture in Freiburg in July 1972 on late antiquity and the early Middle Ages in the area between Lake Geneva and the Upper Rhine .

After another stay at the German Historical Institute in Rome from 1972 to 1973, Keller worked as a university lecturer in Freiburg. In 1976 he was appointed adjunct professor . In 1978 he received a C3 professorship for medieval history at the University of Freiburg. In 1979/80 he was dean of the Philosophical Faculty IV and spokesman for the Joint Committee of the Philosophical Faculties of the University of Freiburg. From 1980 to 1982, Keller headed the regional history department in the history seminar.

In 1982 he was appointed to succeed Karl Hauck at the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster , where he was full professor for medieval history and co-director of the institute for early medieval research until his retirement in 2002. He gave his inaugural lecture in June 1983 on population growth and social organization in the European High Middle Ages using the example of Northern Italian agricultural society during the 12th and 13th centuries. In Münster, Keller was one of the founders and long-time spokesman for the Collaborative Research Center “Carriers, Fields, Forms of Pragmatic Writing” and the Graduate College “Writing Culture and Society in the Middle Ages”. Keller was instrumental in ensuring that Münster developed into a center of international medieval studies. As an academic teacher, he supervised 25 dissertations and five habilitations. His academic students include Franz-Josef Arlinghaus , Marita Blattmann , Christoph Dartmann , Jenny Rahel Oesterle , Hedwig Röckelein , Thomas Scharff and Petra Schulte . His successor in Münster was Martin Kintzinger . Keller held his farewell lecture in Münster in July 2002 on the overcoming and present of the “Middle Ages” in European modernism. In it he tried to define the current location of the Middle Ages. The widespread social self-image of setting oneself apart from the Middle Ages has been evident since the 15th century. Reform, revolution, rationality and the technical inventions including their economic and military use formed the models and the framework with which one wanted to distinguish oneself from the Middle Ages. The historians of the last three decades would have relativized the epoch boundary around 1500 more and more. The scientific discussion about epoch boundaries and epoch names illustrates a new way of thinking about the relationship between the present and our long past. In view of the increasingly unclear awareness of the epoch, Keller locates the task and topicality of medieval studies in the self-assurance of people, for which knowledge of the past is necessary.

Keller was co-editor of the Propylaea History of Germany from 1982 to 1995 and has been co-editor of the series Münstersche Historische Forschungen since 1991 . From 1988 to 2011 he was editor of the Early Medieval Studies . Since 1980 he has been a member of the commission for historical regional studies in Baden-Württemberg , since 1989 of the Konstanz working group for medieval history and since 1990 of the historical commission for Westphalia . Keller taught as visiting professor at the Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Storici in Naples (1979), at the University of Florence (1997) and at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris (2001). In 2002 he was accepted into the British Academy and in the same year a member of the Royal Historical Society in London. Volume 36 of the Early Medieval Studies was dedicated to him. On the occasion of his 70th birthday in 2007, a conference was held in his honor in Münster, the results of which were published in 2011 in the anthology Between Pragmatics and Performance. Dimensions of medieval written culture were published. On the occasion of his 80th birthday, a colloquium was held in May 2017 at the History Department of the University of Münster. The focus was on current perspectives on the history of the political in the Middle Ages.

plant

Keller submitted over 150 publications. His work on the foundations and manifestations of Ottonian kingship, on the nobility and urban society in Italy, on the upheavals in the Salier and Staufer times and on the early days of the Alemannic duchy are significant . Since 1975 he has worked closely with Gerd Althoff , a student of Keller's mentor Karl Schmid. Their exchange for dealing with Ottonian historiography and the problem complex of group behavior and statehood was particularly fruitful.

Foundations of the Ottonian royal rule

The starting point for Keller's work on the functioning of the Ottonian royal rule is the research of his teacher Gerd Tellenbach. In the 1950s, the “Freiburg Working Group” recognized that entries in the fraternization and memorial books of the early Middle Ages were made in groups. In times of crisis, members of the ruling classes increasingly had the names of their relatives and friends recorded in monasteries' memorial books. This was hidden from older, constitutionally oriented research. The analysis of the memorial tradition brought a completely new understanding of the bonds and contacts that the nobility, church and royalty maintained with one another. This also made the explanations in Ottonian historiography easier to understand. The “Freiburg Working Group ” presented numerous prosopographical as well as aristocratic and social history works, especially on the 10th century. According to Gerd Althoff, the scientific discussion about the “emergence” of the “German” empire was also important for Keller's research. As a result, in 1983, on the occasion of Gerd Tellenbach's 80th birthday, Keller formulated his new view of the “foundations of Ottonian kingship”. His remarks showed that he assessed this royal rule differently than his teacher Tellenbach and some of his older students such as Josef Fleckenstein . According to Fleckenstein, all activities of the king were long-term aimed at strengthening his power over the nobility and the church. Keller, on the other hand, assumed a polycentric system of rule in his analysis of the political order of the Ottonian Empire. In his opinion, a count of the royal courts as well as royal property, taxes, customs duties and other income does not adequately describe the state order and the possibilities for political development in the 10th and 11th centuries. For Keller, acquisition and increase in power were no longer the yardstick for assessing the achievements of the Ottonian rulers, but their integration function. The monarchy had the task of integrating the individual aristocratic lords "through the shaping of personal relationships and thus giving them the quality of a rule and legal system". Under the influence of was with these insights as outdated Nazism by Otto Brunner and Theodor Mayer drawn picture of an on loyalty and allegiance based opposite a leader people federation state . Subsequently, Gerd Althoff examined the personal network of relationships that King and Great established, maintained and, if necessary, changed.

A methodologically important study for understanding Ottonian royal rule is Keller's essay, published in 1982, Reich structure and conception of rule in the Ottonian-Early Salian period , which Gerd Althoff described as the "initial spark" for further research on the foundations of the Ottonian royal rule. In this work, Keller examined the places where documents from Otto I, Heinrich II. And Heinrich III. the relationship between the Ottonian- Salian rulers and the southern German dukes in Bavaria and Swabia. For the first time, the importance of Swabia in the itinerary of the Ottonians and early Salians was examined. Keller observed a profound change in the Ottonian royal rule. Until the time of Otto III. Swabia was only used as a transit country to Italy; the royal stays were as short as possible. From the year 1000, however, the royal rule was publicly demonstrated by “the periodic presence of the court in all parts of the empire”. This essay paved the way for a new understanding of the extent of Ottonian kingship in the empire.

In their 1985 double biography of the first two Ottonians Heinrich I and Otto I , Hagen Keller and Gerd Althoff made intensive use of the knowledge about medieval prayer commemoration. In particular, the remembrance of prayer in the Ottonian house monasteries of Lüneburg and Merseburg gave an impression of the family and alliances of the noble owners. Amicitiae (friendship alliances ) became the central instrument of rule of Henry I in dealing with the great , convivia (common ritual meals) were the starting points for political alliances and conspiracies. For Althoff and Keller, the first two Ottonian rulers were no longer symbols of Germany's early power and greatness, but rather representatives of a modern, distant, archaic society. Keller and Althoff made a structural change in the rule of Heinrich I and Otto I. As king, Heinrich achieved a settlement with numerous rulers with the help of formal alliances of friendship. For Keller and Althoff, the arrangement made with the dukes on the basis of these friendships was one of the “foundations for rapid success in stabilizing the royal rule”. Heinrich's son Otto I, on the other hand, did not continue these mutually binding alliances (pacta mutua) with the greats of his empire and thus provoked conflicts. Otto took no account of the claims of his relatives and the nobility; rather, it was about enforcing his royal decision-making powers. By adopting Carolingian traditions, Otto clarified the distance between the king and the nobility. In view of the friendship alliances between Heinrich and the dukes of southern Germany, Althoff and Keller took the view that, according to the understanding of the time, "the dukes' claims were hardly less founded or justified than his own claim to the royal rule". According to this, it was only logical that Heinrich renounced an additional legitimation of his kingship by renouncing the anointing when he was raised as king. The knowledge about the meaning and importance of the Amicitia alliances also relativized the image of an anti-clerical king drawn in older research . Heinrich concluded the prayer fraternities with both spiritual and secular greats. According to Althoff and Keller, the friendship pacts with the dukes also created new room for maneuver for the king. The big ones themselves had ties and obligations that crossed the borders of the empire. The arrangement with the dukes and the associated increase in power and fame gave the king new opportunities to work to his advantage in the neighboring areas of the empire.

At the German Historians' Day in 1988 in Bamberg , Keller headed the section “Group ties, rule organization and written culture among the Ottonians”. At that time he dealt with the fundamental problem of “statehood” in the early Middle Ages and gave a lecture “On the character of“ statehood ”between the Carolingian reform of the empire and the expansion of rule in the high Middle Ages”. According to Keller, the political culture of the Ottonians in the 10th century cannot be grasped with the categories of modern statehood. Ottonian rule managed largely without written form, without institutions, without regulated competences and instances, but above all without a monopoly of force. Rather, the political order of the Ottonian period was characterized by orality, rituals and personal ties, while the Carolingian empire was characterized by writing, institutions, a strong centralized form of rule and the royal allocation of offices. The possibilities and limits of royal rule in the 10th century under these conditions were examined in Bamberg by Gerd Althoff with a view to the institutional mechanisms of conflict settlement and resolution between the king and the great and by Rudolf Schieffer based on the relationship between the episcopate and the king. The lectures held in Bamberg appeared in 1989 in the Early Medieval Studies and are an important starting point for a reassessment of Ottonian royal rule.

The findings of the memorial tradition also created new conditions for reading the works of Ottonian historiography. Karl Schmid had come across an entry in the Reichenau memorial book in the course of indexing the monastic memorial books from the Carolingian and Ottonian times, which Otto referred to as rex as early as 929 . His research contributions from 1960 and 1964 on the succession to the throne of Otto I introduced new facts into the scientific discussion. Until then, research was based solely on the information provided by Widukind von Corvey , whose history in Saxony seemed to indicate that King Heinrich I had chosen his eldest son Otto as his successor in 936 and thus shortly before his death. In an essay on Widukind's report on Otto the Great's rising as king in Aachen, which arose in 1995 in connection with the discussion about criticism of memory and tradition, Keller emphasized the importance of the results that Karl Schmid had gained on the basis of the memorial tradition: You "Enable and enforce a different type of access: namely to check the representation intention and its 'deforming' effect on the 'reporting' at a central point by confronting different information". At the same time, Johannes Fried pointed out that historical events are subject to a strong deformation process. The historical memory "changed incessantly and imperceptibly, even during the lifetime of those involved". The resulting view of the past was, according to Fried, "never identical with actual history". The Saxon history of Widukind von Corvey, the main source for the early Hottonian kingship, is for Fried "a construct saturated with errors". Based on Schmid's work on a possible succession plan for Heinrich I as early as 928/29, Keller again devoted himself to the Widukind criticism. In contrast to the approach of the unreliability of Ottonian historiography, elaborated by the historians Fedor Schneider , Martin Lintzel and Carlrichard Brühl and pursued by Johannes Fried, Keller concentrated on the effects of an intentionally shaping and deformed representation that seeks to show something specific in the event. Keller fundamentally doubted whether it was legitimate to apply ethnological methods to research completely written cultures on a literarily trained medieval historian like Widukind. Rather, Widukind had represented his point of view "based on the entire arsenal of literary design possibilities of a traditional written culture". Against Fried's criticism of the tradition, Keller objected that there were still contemporary witnesses in 967/68 who had directly witnessed the events of the king elevations and succession regulations in 919, 929/30 and 936. One could not ignore her memory. It is known from Italian witness interrogations of the 12th and 13th centuries that the oldest respondents said they could remember back up to 70 years. According to Keller, a king's elevation with simultaneous anointing took place in the Ottonian period for the first time in 961 and not as early as 936. Widukind's report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I in 936 was understood by Keller as a back projection of the historian based on the model of the coronation and anointing of Otto II in 961 in Aachen, at which he was present as a witness. Keller had already put forward this thesis in lectures in 1969 and 1972. Otto's spiritual consecration took place in Mainz as early as 930. In doing so, Keller refers to a note from the 13th century Lausanne annals, which gained new meaning through Schmid's work on Heinrich's succession plan in kingship. The Aachen act of 936 only appears as a demonstration of power. According to Keller, this reconstruction also clarifies the previously "rather confused appearing history of the right to coronation and the place of coronation in the Roman-German Empire". But it does not expose Widukind as a fabulist. Rather, Keller evaluates Widukind's portrayal of “self-experienced” history as an opinion on current issues. Widukind's description of the coronation should be understood as a criticism of the growing influence of the church on the legitimation of rule and of the increasing sacralization of kingship. The historian opposes this development with the “divine plan of salvation”, ie the rise of the Saxons to kingship as an expression of divine activity, and the warrior kingship. Keller came to completely different results than Hartmut Hoffmann , who rejected Schmid's theses about a decision on the succession in 929/30 and the associated early anointing of Otto.

In a further investigation, Keller tries to show that Widukind's view of history with regard to the Ottonian kingship was shaped by biblical ideas. The admonitions that Judas Maccabeus or his brothers are supposed to have addressed to their troops before the start of a battle are comparable to the speeches of the Saxon kings Heinrich and Otto before the battles of Hungary in 933 and 955. The Maccabees commanders admonished their followers to give up their whole trust To set God and the victories granted by God to their forefathers and to stand up for the validity of the divine law with their lives. The enemies, on the other hand, could only rely on their superior strength and their own weapons. According to Widukind, the military successes of King Heinrich and his son Otto repeated the victories that God had granted the Maccabees against the overwhelming power of godless enemies.

When examining the portrayal of rulers in the Ottonian historiography of the 960s (Widukind, Liudprand von Cremona and Hrotsvit ), Keller refuses "to interpret the authors' statements simply as evidence of a free-floating history of ideas of royalty". Rather, according to Keller, the statements of Ottonian historiography were "directly related to life" and their formulations should be understood as a "statement on questions that moved the inner circle of the court, the power bearers of that time".

By examining various types of sources (historiography, symbols of rulership, images of rulers), Keller was able to work out a fundamental link between the Ottonian kingship and Christian ethics. In his studies on the change in the image of the ruler on the Carolingian and Ottonian royal and imperial seals, he no longer understood them to be mere propaganda for rule, but took greater account of the liturgical tradition. He observed a fundamental change in the representation of power under Otto the Great. After the coronation of the emperor in 962, the depiction of the ruler on the seals changed from a Frankish-Carolingian model to a ruler based on the Byzantine model: the half-figure of the king in side view becomes the depiction of the emperor in the frontal image. Keller examined the portrait of the ruler in the Codex of the Vatican Apostolic Library Ottobonianus latinus 74, which is kept in Montecassino . He wants this manuscript from the time of Henry III. ("At 1045/47") assign. The picture of the ruler on folio 193v does not represent Heinrich II , but Heinrich III. For his thesis he relies on Wipo's Tetralogus and shows similarities in the understanding of rule between miniature and literary work. Up until Keller's interpretation, the portrait had always been related to Heinrich II.

For a reassessment of the early and high medieval royal rule, symbolic communication also became important. In close cooperation with Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller thought about demonstrative, ritual and symbolic ways of acting in the Ottonian era. Research into rituals and forms of symbolic communication led to the realization that the Ottonian historians' intent to depict is primarily focused on the ruler's ties and obligations to God and the faithful. In view of the importance of personal ties and symbolic forms of communication, Gerd Althoff developed the pointed thesis of the Ottonian “royal rule without a state”.

In addition to the lack of institutional penetration of the Ottonian empire, the exercise of power based on consensual ties is a central criterion in Keller's analysis of the foundations of Ottonian kingship. According to Keller, the king received his dignity and authority from the consensus of his faithful and from the order legitimized by God, as their trustee he appeared. In an investigation into the role of the king in the appointment of bishops in the Ottonian and Salier empires, Keller showed that the doctorates were mostly the consensual result of negotiations between the ruler and the cathedral chapter .

In 2001, Keller published a concise account of the Ottonian history for a wider audience. This overview was published in its fourth edition in 2008 and was translated into Czech in 2004 and into Italian in 2012. In 2002, on Keller's 65th birthday, seven essays published between 1982 and 1997 were part of the anthology Ottonische Königsherrschaft. Organization and legitimation of royal power reissued. Together with Gerd Althoff, Keller wrote Volume 3 of the new “Gebhardt” ( Handbook of German History ) , published in 2008, about the time of the Late Carolingians and Ottonians. Keller wrote the section on the time from the end of the Carolingian Empire to the end of Otto II's reign . The chapter "Orders and forms of life" was written by both authors together. Their declared aim was a “fundamental revision of the traditional image of history”, that is, the “denationalization of the image of the Ottonian empire”.

Italian urban communes and written culture in the Middle Ages

Since around 1965, the fields of relationships between people and families in the Middle Ages have been researched with the help of private documents . This new approach was implemented by Gerd Tellenbach and his students using examples from Tuscany and Lombardy . The detailed research of the rulership structures on the basis of private documents was also of particular importance for the city's history. In 1969, Keller presented his first study on Italy. In it he dealt with the place of jurisdiction within the larger cities of Tuscany and northern Italy from the 9th to the 11th centuries and drew conclusions about the balance of power between king, bishop, count and urban patriciate . The investigation shows how the rising forces in the cities, the Capitani (high nobility) and the Valvassors , slipped away from the influence of the ruler. Keller also states that the material basis of the Lombard-Italian kingship has collapsed : imperial property and imperial rights were lost to the feudal nobility. In his post-doctoral thesis Adelsherrschaft und Stadtgesellschaft in Oberitalien , published in 1979, he no longer only focuses on the high aristocracy of the counts and margraves , but also on the middle nobility, the capitani and valvassors , known as episcopal (sub) vassals . Keller first analyzes the development of the terms plebs , populus , civis , capitaneus and valvassor in the 11th and 12th centuries. He then examines the wealth situation of captains, farmers and Valvassors. He sees the cause of the northern Italian vassal uprisings at the end of the 10th and beginning of the 11th century in the "revindication of church property and imperial rights that were left to the churches". So it was about resistance to measures that endangered the position of the nobility. In terms of social development, Keller states "a constancy of the aristocratic upper class from the late 9th to the 12th century and a social dynamic below this aristocratic leadership group, which was shaped by changes in the structures of rule and strengthened by economic development". Since the study mainly evaluated Milanese sources, it was perceived in Italy primarily as a study of Milan and its sphere of influence. However, Keller wanted to use a regional example to show “how far and in what forms the social history of Northern Italy integrated into the general developments of the société féodale during the 10th – 12th centuries . Century was included ". Keller's work, translated into Italian in 1995, is considered to be one of the most important case studies on Italian municipalities.

In 1986 the new Medieval Collaborative Research Center 231 was set up at the University of Münster on the subject of "Carriers, fields, forms of pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages". The occasion for an interdisciplinary research project on the development of European written culture in the Middle Ages was the international debate that took place in the 1960s and 1970s on communication conditions in oral societies . The work of the Collaborative Research Center was based on this research situation. The collaborative research center initiated and directed by Keller resulted in numerous works on the pragmatics of writing itself or on the function of administrative writing in the northern Italian municipalities. The Collaborative Research Center dealt with the development of European literacy from the 11th to the early 16th century. According to the first application in 1985, this was the epoch in which writing was given “a life-determining function for society as well as for the individual”. The 11th and 12th centuries were seen as the decisive transition phase for northern Italy. During this time, writing expanded to include all areas of human interaction. The research program of the Collaborative Research Center was implemented in seven sub-projects from 1986 onwards. The results presented and discussed at four international colloquia have been published in four extensive volumes. Pragmatic writing is understood as action-oriented writing. As “pragmatic” in the sense of the research program, all “forms of written form that directly serve purposeful action or that want to guide human action and behavior through the provision of knowledge” are understood, that is, “written material, for the creation and use of which the requirements of everyday life were constitutive ". Keller dealt with pragmatic writing, especially with regard to the Italian urban communes and the communal societies of the High Middle Ages.

From 1986 to 1999, Keller was in charge of sub-project A, “The writing process and its sponsors in Northern Italy” within the framework of the Collaborative Research Center 231. From the 12th century, the source base in communal Italy expanded. The written documentation for government and administration increased there to an extent for which there is no parallel in Europe, despite the general increase in written form. According to Keller, three factors have particularly favored the writing process in the administration of the Italian municipalities. The first was the time limitation of the municipal office; In order to ensure continuity, it required the administrative activities and procedural steps in the administration of justice to be laid down in writing. Second, the fear of abuse of office led to a detailed definition of official powers and the rules of conduct for public officials, in order to be able to check that office conduct and administrative actions are correct. If the regulations were violated, sanctions had to be determined. The third factor was the increasing efforts of the community to provide for the livelihood, security and prosperity of the community. The expansion of the use of writing in communal Italy brought about a new type of source in the form of the statute codes, the comprehensive collections of the applicable statute law, the origin, early history, structure and social significance of which Keller examined with his research project. The setting of norms by statutes is understood as an expression of a profound cultural change in the Italian municipalities. The sharp increase in the written form was therefore accompanied by a large number of new statutory provisions, a systematic arrangement of the statutes and a periodic re-editing. Within a few decades, the forms of legal security and legal process changed fundamentally.

The research project on the pragmatic use of writing in municipal Italy initially focused on the modernization of government and administration. However, further research also made the disadvantages of writing clear. The written form has brought about increased regulation of farm management and village life. The rural communities, for example, were told how much grain they had to deliver into the city, broken down by type. In the increasing number of lease agreements, the taxes for the individual crops were specified in detail. The farmers' livestock farming was reduced. The urban communities forbade the mountain population to keep pack animals. Only millers and carters were allowed to keep a precisely defined number of these animals; they had to carry registration papers with them for police checks.

Keller and his research group in Münster were able to use numerous examples to show how continuously and seamlessly administrative and governmental action was written down in Italian municipalities. This was accompanied by a new way of dealing with the records. Through targeted archiving, files could be found and used again even after generations. The written documentation helped, for example, in times of need to ensure the care of one's own citizens, and it also made it easier to track down heretics . According to Thomas Scharff , a colleague of Keller's, the medieval heretic inquisition was "inconceivable at all without the increase in pragmatic writing."

Based on his investigations into the administrative documents in the Italian municipalities, which grew immensely from the end of the 12th century, Keller dealt with the social concomitant phenomena and anthropological consequences of this writing process. He asked about the importance of writing for world orientation and strategies of action of people. His thesis is "that forms of cognitive orientation linked to written form are of immediate importance for the process of individualization that can be traced in European society since the High Middle Ages". These considerations are related to the general discussion about the emergence of individuality from the 12th century onwards. Based on the tax collection and the grain and supply policy, Keller showed that the living conditions of every individual citizen in the municipality were incorporated into controllable procedures through administrative writing. The writing process around 1200 also resulted in a profound change in legal life in Italian cities. The writing of the law meant that the individual could break out of group ties and locate himself in the political and social order.

Symbolic communication

The sub-project “ Certificate and Book in the Symbolic Communication of Medieval Legal Communities and Ruling Associations”, led by Keller, was part of Collaborative Research Center 496: Symbolic Communication and Social Value Systems from the Middle Ages to the French Revolution . One of the central questions of the Collaborative Research Center was: “When and why were acts of symbolic communication changed, introduced or dispensed with older ones?” In this sub-project, too, municipal Italy was a focus of the investigations. The project dealt with the possibilities of interpreting the use of writing in its communicative context. The aim was to gain new insights into the creation and use of ruling documents in the early and high Middle Ages.

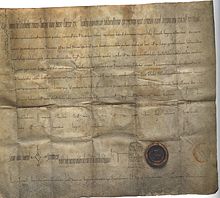

The inclusion of symbolic communication contributed to a reassessment of the written form. According to Keller, documents were "the most important and at the same time the most solemn medium of written communication" in ruling associations and legal communities of the early Middle Ages. In the ruler's deeds, Keller pleaded for greater consideration of the so far little researched act of privilege and the circumstances that led to the creation of the deeds. A comprehensive and appropriate assessment of the historical significance of a document is only possible if the symbolic communication is taken into account. Keller assumes a close intertwining of the document text and symbol-laden public interaction. Only when the respective overall structure and statement and the respective historical situation are taken into account in a diploma, the prerequisites for a better understanding of privilege and act of privilege are given. Keller therefore sees documents not only as text or legal documents, but as a means of representation and self-portrayal of the ruler and as "emblems" in the communication between the king and his loyal followers. According to Keller, the act of issuing documents was less an expression of a free will to rule, but rather the result of a process of communication and consensus-building between the ruler and various interest groups. The privilege is to be interpreted as a ritually shaped communication event that goes far beyond the mere act of handing over the documents. The direct context of creation and use of a document can be better understood through its classification in solemn acts. Parts of the certificate are to be interpreted as targeted communicative signals. A ruler's charter that fixes a legal issue in writing becomes a source for a specific situation in the medieval ruling association. According to Keller's research, the “elements of the culture of writing to ensure authenticity” in the early and high Carolingian documents were replaced by a greater public and representativeness in the act of notarization. The monogram completed by the king and the seal were enlarged and clearly separated from the text. The “visual presentation of the document” seems to be “embedded in a change in the public communication between the ruler and his followers”. This type of sealing took into account the poor literacy of the secular office holders. As a result, the document became a symbol of communication in the 10th century. According to Keller, the status of notarial acts and documents changed during the 11th and 12th centuries, because the perceptions about the social foundations of law and the guarantee of law through rule and community changed. From the middle of the 12th century onwards, an expansion of the use of writing and a differentiation of business documents can be observed.

Changes in the Salier and Staufer times

In an essay published in 1983 on the behavior of Swabian dukes of the 11th and 12th centuries as aspirants to the throne, Keller introduced a paradigm shift in German-speaking medieval studies with the idea of “prince responsibility for the empire” . His new research approach was based on the motives of the great and the fundamental relationship between king, prince and empire as a whole. Keller ascertained a change in the understanding of elections in the 11th and 12th centuries and was able to show that the behavior of the Swabian dukes had other motives than the previously assumed motive “self-interest of the princes”. Since 1002, and increasingly since 1077, the princes have claimed to be able to "act as a group for the empire [...] and assert themselves as the general public against special interests". This made the empire “an association capable of acting even without the king”. With this point of view, Keller opposed the older research opinion, which saw the princes as “gravedigger of the empire”, whose behavior contributed to the decline of the royal central authority over the course of the Middle Ages.

Keller's account of the High Middle Ages in the second volume of the Propylaea History of Germany (1986) was widely recognized in medieval research. The book is divided into the three main parts The Empire of the Salians in the Upheaval of the Early Medieval World (1024–1152) (pp. 57–216), The Reorganization of Living Conditions in the Development of Human Thought and Action (pp. 219–371) and That German empire between world empire, full papal authority and princely power (1152–1250) (pp. 375–500). In his portrayal, Keller no longer interpreted the conflicts in the time of the Salians and Staufers as disputes between royalty and nobility, but rather described the "rule of kings in and above the ranking of the greats". Fighting insurrections was an essential part of the Salian rule. According to Keller, conflicts arose wherever changes in the hierarchy and the power structure threatened. If offices or fiefs had to be re-assigned after the death of their owners, a dispute arose. One of the king's central rulers' tasks was to settle local conflicts. Unlike historians like Egon Boshof or Stefan Weinfurter , Keller viewed the increasing criticism of Heinrich III's government . in the last decade of his rule not as a sign of a fundamental crisis, otherwise the whole Ottonian and Salian period would have to be described as a crisis epoch.

In a lecture given in September 2000 and published in 2006, Keller noted a change in social values in the 12th century. He observes a clearer emergence of the individual personality in society. At the same time, a change in the political order becomes visible, which has integrated the personal existence of the people more strongly than before in universally valid norms. According to Keller, both developments belong together as complementary phenomena. On the basis of numerous political and social changes, he substantiates his thesis of an interweaving of the order of the community and responsibility of the individual. Since the 12th century, the oath has not only gained greater importance, but through the taking of the oath the individual has now become bound to the whole of the political association. Since the 12th century, an innovation in the oath has been a self-commitment to the principles of living together in a community. In addition, not only the legal system changed in the 12th century, but above all the conception of law. In criminal law, the understanding of punishment and guilt has changed: the act committed in personal responsibility should no longer be compensated for with a compositio , but with a just punishment, graded according to the severity of the offense. Keller devoted further publications to the changes and upheavals in the 12th century.

Scientific aftermath

With his analysis of the Ottonian kingship, his constitutional and regional historical observations on the sovereign penetration of a territory by kingship, with his research into rituals and conflicts, as well as with his explanations about documents and seals as carriers of communication between the ruler and the recipient of the documents, Keller played an essential part the reassessment of high medieval royalty, which began in research in the 1980s. In an overview , Hans-Werner Goetz (2003) sees the early medieval royal rule primarily shaped by rituals and the representation of power.

Keller's 1982 results on the exercise of royal rule, which included all parts of the empire around 1000, were widely recognized in research. In 2012, however , in contrast to Keller's view of the integration of the southern German duchies, Steffen Patzold viewed Swabia as a fringe zone of the empire even under Henry II, as not a single synod , which met in the presence of Henry II, took place in Swabia. The celebration of a solemn festival (Christmas, Easter and Pentecost), which was considered an act of royal representation and exercise of power, only took place once in Swabia. Patzold also referred to the documentary material: Only 5 percent of all Heinrich II documents were issued in Swabia.

The interpretation of rulers' deeds as visual media, advocated by Keller and his research group, has become generally accepted in historical studies. More recent works hardly perceive certificates as mere texts.

The works that emerged from the project “The Writing Process and Its Carriers in Northern Italy” between 1986 and 1999 have so far only been received selectively in Italian medieval research - probably mainly for linguistic reasons.

In 2001 August Nitschke spoke out against an overemphasis on the contrast between “Carolingian statehood” and Ottonian “royal rule without a state” . His remarks conclude with the result: “The transition from Carolingian statehood to personal rule of the Ottonians, to a 'union state', does not have to be explained; because there was no such thing as 'statehood' among the Carolingians ”. In other studies, too, for example by Roman Deutinger and Steffen Patzold, the contrast emphasized by Keller between the forms of rule of the Carolingian and Ottonian times is viewed as far less profound.

Keller and Althoff's research on Amicitia alliances and oaths, polycentric rule, written culture, rituals and symbols resulted in a considerable gain in knowledge. Their view of the Ottonians was received strongly in contemporary medieval studies. Her double biography of Heinrich I and Otto der Große , published in 1985, was supplemented in 2008 by the biography of Wolfgang Giese to reflect the current state of research. In a work published in 2001, Jutta Schlick examined the elections for kings and the court days from 1056 to 1159 , primarily on the basis of Keller's research. In her Passau habilitation thesis published in 2003, Elke Goez dealt with the pragmatic written form by “examining the administrative and archive practice of Cistercians , their handling of their own documentary and administrative documents ”.

Most of Keller's students were also employees of the Münster Collaborative Research Center; their positions were funded by the German Research Foundation as part of the Collaborative Research Center . The investigations therefore remained largely focused on the topic of the research project headed by Keller “The writing process and its sponsors in Northern Italy”. As a result, a “school” in the sense of a group of students with a common research area could develop in Münster: Roland Rölker examined the role of different families in the Contado (surrounding area claimed as a dominant and economic area) and in the municipality of Modena , Nikolai Wandruszka analyzed the social role Development of Bologna in the High Middle Ages, Thomas Behrmann followed the process of writing from the 11th to the 13th centuries using the two document collections in Novara, the cathedral chapter of S. Maria and the chapter of the basilica of S. Gaudenzio that was split off from it, and analyzed the sharp increase in written documents In the first decades of the 13th century, Jörg W. Busch dealt with the history of Milan from the late 11th to the early 14th century, Petra Koch worked on the Vercelles municipal statute codes of 1241 and 1341 and Peter Lütke Westhues on the Veronese municipal statutes of 1228 un d 1276. Patrizia Carmassi analyzed the use and application of liturgical books in the ecclesiastical institutions of the city of Milan from the Carolingian period to the 14th century, Thomas Scharff traced the use of writing in the context of the Inquisition in several contributions , Christoph Dartmann explored the beginnings the Milanese commune (1050–1140), the consular commune of Genoa in the 12th century and the urban commune in Florence around 1300 and Petra Schulte dealt with trust in the notarial deeds of Northern Italy from the 12th and 13th centuries.

Fonts

A list of publications appeared in: Thomas Scharff, Thomas Behrmann (ed.): Bene vivere in communitate: Contributions to the Italian and German Middle Ages. Hagen Keller presented by his students on his 60th birthday. Waxmann, Münster 1997, ISBN 3-89325-470-6 , pp. 311-319.

Monographs

- The Ottonians. 5th updated edition. Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-44746-4 .

- with Gerd Althoff : The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-60003-2 .

- Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-534-15998-5 .

- with Gerd Althoff: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen a. a. 1985, ISBN 3-7881-0122-9 .

- Between regional limits and a universal horizon. Germany in the empire of the Salians and Staufers 1024 to 1250 (= Propylaea history of Germany. Vol. 2). Propylaeen-Verlag, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-549-05812-8 .

- Aristocratic rule and urban society in Northern Italy. 9th to 12th century (= library of the German Historical Institute in Rome. Vol. 52). Niemeyer, Tübingen 1979, ISBN 3-484-80088-7 (Partly at the same time: Freiburg (Breisgau), habilitation thesis, 1971 under the title: Keller, Hagen: Seniors and Vasallen, Capitans and Valvassors. T. 1).

- Einsiedeln Abbey in Ottonian Swabia (= research on the history of the Upper Rhine region. Vol. 13). Alber, Freiburg i. Br. 1954.

Editorships

- with Marita Blattmann: Carrier of the writing and structures of the tradition in northern Italian municipalities of the 12th and 13th centuries (= scientific writings of the WWU Münster. Vol. 25). Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster 2016, ISBN 3-8405-0142-3 .

- with Christel Meier , Volker Honemann , Rudolf Suntrup: Pragmatic Dimensions of Medieval Writing Culture. Files of the International Colloquium Münster May 26-29, 1999 (= Münstersche Mittelalter-Schriften. Vol. 79). Fink, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7705-3778-5 . ( Digitized version )

- with Christel Meier, Thomas Scharff: Writing and practical life in the Middle Ages. Capture, preserve, change. (Files from the international colloquium June 8-10, 1995) (= Münstersche Mittelalter-Schriften. Vol. 76). Fink, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-7705-3365-8 . ( Digitized version )

- with Franz Neiske: From monastery to monastery association. The tool of writing. Files from the international colloquium of the L 2 project in the SFB 231, February 22-23, 1996 (= Münstersche Mittelalter-Schriften. Vol. 74). Fink, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7705-3222-8 . ( Digitized version )

- with Thomas Behrmann: Communal documents in Northern Italy. Forms, functions, tradition (= Munster medieval writings. Vol. 68). Fink, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-7705-2944-8 .

- with Klaus Grubmüller, Nikolaus Staubach: Pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages. Appearances and stages of development. (Files from the international colloquium, May 17-19, 1989) (= Münstersche Mittelalter-Schriften. Vol. 65). Fink, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7705-2710-0 ( digitized version )

literature

- Gerd Althoff : The Scripture Scholar. For the sixtieth birthday of the historian Hagen Keller. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , May 2, 1997, No. 101, p. 40.

- Christoph Dartmann , Thomas Scharff, Christoph Friedrich Weber (eds.): Between pragmatics and performance. Dimensions of medieval literary culture (= Utrecht studies in medieval literacy. Vol. 18). Brepols, Turnhout 2011, ISBN 978-2-503-54137-2 .

- Thomas Scharff , Thomas Behrmann (Ed.): Bene vivere in communitate: Contributions to the Italian and German Middle Ages. Hagen Keller presented by his students on his 60th birthday. Waxmann, Münster 1997, ISBN 3-89325-470-6 .

- Keller, Hagen. In: Kürschner's German Scholars Calendar. Bio-bibliographical directory of contemporary German-speaking scientists. Vol. 2: H - L. 26th edition. de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-030257-8 , pp. 1730f.

- Hagen Keller. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): The Constance Working Group for Medieval History. The members and their work. A bio-bibliographical documentation (= publications of the Constance Working Group for Medieval History on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary 1951–2001. Vol. 2). Thorbecke, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-7995-6906-5 , pp. 217-224 ( online )

- Who is who? The German Who's Who. LI. Edition 2013/2014, p. 547.

Web links

- Literature by and about Hagen Keller in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications by Hagen Keller in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- Page from Hagen Keller at the Institute for Early Medieval Research at the University of Münster

- Intervista a Hagen Keller / Interview with Hagen Keller, a cura di Paola Guglielmotti, Giovanni Isabella, Tiziana Lazzari, Gian Maria Varanini. In: Reti Medievali Rivista. Vol. 9, 2008 (Italian version / German version) .

Remarks

- ↑ Intervista a Hagen Keller / Interview with Hagen Keller , a cura di Paola Guglielmotti, Giovanni Isabella, Tiziana Lazzari, Gian Maria Varanini. In: Reti Medievali Rivista. Vol. 9, 2008, p. 10 ( online ).

- ↑ Intervista a Hagen Keller / Interview with Hagen Keller , a cura di Paola Guglielmotti, Giovanni Isabella, Tiziana Lazzari, Gian Maria Varanini. In: Reti Medievali Rivista. Vol. 9, 2008, pp. 3ff. ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Overcoming and Presence of the “Middle Ages” in European Modernism. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 37, 2003, pp. 477–496, here: p. 487 (accessed via De Gruyter Online). See also Intervista a Hagen Keller / Interview with Hagen Keller, a cura di Paola Guglielmotti, Giovanni Isabella, Tiziana Lazzari, Gian Maria Varanini for the résumé. In: Reti Medievali Rivista. Vol. 9, 2008, pp. 1ff. ( online ).

- ^ Karl Schmid: 'The Freiburg Working Group'. Gerd Tellenbach on his 70th birthday. In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. Vol. 122, 1974, pp. 331-347.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Aristocratic rule and urban society in Northern Italy. 9th to 12th centuries. Tübingen 1979, foreword XIf.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages in the area between Lake Geneva and the Upper Rhine. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 7, 1973, pp. 1-26 ( online ).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Changes in the rural economy and life in northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries. Population growth and social organization in the European High Middle Ages. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 25, 1991, pp. 340-372 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Overcoming and Presence of the “Middle Ages” in European Modernism. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, pp. 477-496 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Overcoming and Presence of the “Middle Ages” in European Modernism. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, pp. 477–496, here: p. 480 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Overcoming and Presence of the “Middle Ages” in European Modernism. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, pp. 477–496, here: p. 487 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Christel Meier : 50 Years of Early Medieval Studies. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 50 (2016), pp. 1–13, here: pp. 12 f.

- ↑ Cf. Jenny Oesterle: Conference report: Between pragmatics and performance - dimensions of medieval written culture, May 2nd, 2007 - May 4th, 2007 Münster. In: H-Soz-Kult , June 3, 2007 ( online ).

- ↑ Current Perspectives on a History of the Political in the Middle Ages. A colloquium on the occasion of Hagen Keller's 80th birthday, May 5, 2017, Münster. In: H-Soz-Kult , April 18, 2017, ( online ).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The high medieval monarchy. Accents of an unfinished reassessment. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 45, 2011, pp. 77–98, here: p. 82. Hagen Keller: Group ties, rules of the game, rituals. In: Claudia Garnier, Hermann Kamp (Ed.): Rules of the game for the mighty. Medieval politics between custom and convention. Darmstadt 2010, pp. 19–31, here: p. 29.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Group ties, rules of the game, rituals. In: Claudia Garnier, Hermann Kamp (Ed.): Rules of the game for the mighty. Medieval politics between custom and convention. Darmstadt 2010, pp. 19–31, here: p. 29.

- ^ Hans-Werner Goetz: Modern Medieval Studies. Status and perspectives of medieval research. Darmstadt 1999, pp. 158-159.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Memoria, writing, symbolic communication. To reevaluate the 10th century. In: Christoph Dartmann, Thomas Scharff, Christoph Friedrich Weber (eds.): Between pragmatics and performance. Dimensions of medieval writing culture. Turnhout 2011, pp. 85–101, here: p. 92.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Foreword. In: Hagen Keller: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 7-10, here. P. 8.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Memoria, writing, symbolic communication. To reevaluate the 10th century. In: Christoph Dartmann, Thomas Scharff, Christoph Friedrich Weber (eds.): Between pragmatics and performance. Dimensions of medieval writing culture. Turnhout 2011, pp. 85–101, here: p. 94.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Memoria, writing, symbolic communication. To reevaluate the 10th century. In: Christoph Dartmann, Thomas Scharff, Christoph Friedrich Weber (eds.): Between pragmatics and performance. Dimensions of medieval writing culture. Turnhout 2011, pp. 85–101, here: p. 88.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Basics of Ottonian royal rule. In: Karl Schmid (Ed.): Empire and Church before the Investiture Controversy. Gerd Tellenbach on his eightieth birthday. Sigmaringen 1985, pp. 17-34, here: pp. 17f.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Basics of Ottonian royal rule. In: Karl Schmid (Ed.): Empire and Church before the Investiture Controversy. Gerd Tellenbach on his eightieth birthday. Sigmaringen 1985, pp. 17-34, here: p. 26.

- ^ Theodor Mayer: The formation of the foundations of the modern German state in the high Middle Ages. In: Hellmut Kämpf (Ed.): Rule and State in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 1956, pp. 284-331. Compare with Gerd Althoff: The high medieval monarchy. Accents of an unfinished reassessment. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien , Vol. 45 (2011), pp. 77-98, here: pp. 81f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Gerd Althoff: Relatives, friends and faithful. On the political significance of group ties in the early Middle Ages. Darmstadt 1990.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Foreword. In: Hagen Keller: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 7-10, here. P. 8.

- ^ Review by Nathalie Kruppa in: Concilium medii aevi. Vol. 7, 2004, pp. 1023-1028, here: p. 1025 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Empire structure and conception of rule in the Ottonian-Early Salian times. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 16, 1982, pp. 74-128, here: p. 90 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Foreword. In: Hagen Keller: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 7-10, here: p. 8.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1–2, Göttingen et al. 1985. Cf. Thomas Zotz : Amicitia and Discordia. On a new publication on the relationship between royalty and nobility in the early Ottonian period. In: Francia Vol. 16 (1989), pp. 169-175 ( online ).

- ^ Hans-Werner Goetz: Modern Medieval Studies. Status and perspectives of medieval research. Darmstadt 1999, p. 161.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1, Göttingen et al. 1985, p. 14.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1, Göttingen et al. 1985, p. 81.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1, Göttingen et al. 1985, pp. 112-133.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1, Göttingen et al. 1985, p. 69.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1, Göttingen et al. 1985, p. 65.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1, Göttingen et al. 1985, pp. 99f.

- ↑ Group ties, rule organization and written culture among the Ottonians (with contributions by Gerd Althoff, Joachim Ehlers, Hagen Keller, Rudolf Schieffer). In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 23, 1989, pp. 244-317.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Group ties, rules of the game, rituals. In: Claudia Garnier, Hermann Kamp (Ed.): Rules of the game for the mighty. Medieval politics between custom and convention. Darmstadt 2010, pp. 19–31, here: p. 26.

- ^ Karl Schmid: New sources for understanding the nobility in the 10th century In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. Vol. 108, 1960, pp. 185-232, esp. Pp. 185-202 ( online ); Karl Schmid: The succession to the throne of Otto the great. In: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History. German Department. Vol. 81, 1964, pp. 80-163.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Foreword. In: Hagen Keller: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 7-10, here. P. 9.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: p. 397 ( online ).

- ↑ Johannes Fried: The Ascension of Henry I as King. Memory, Orality and Formation of Tradition in the 10th Century. In: Michael Borgolte (Ed.): Medieval research after the turn. Munich 1995, pp. 267-318, here: p. 273.

- ↑ Johannes Fried: The Ascension of Henry I as King. Memory, Orality and Formation of Tradition in the 10th Century. In: Michael Borgolte (Ed.): Medieval research after the turn. Munich 1995, pp. 267-318, here: p. 277.

- ↑ Johannes Fried: The Ascension of Henry I as King. Memory, Orality and Formation of Tradition in the 10th Century. In: Michael Borgolte (Ed.): Medieval research after the turn. Munich 1995, pp. 267-318, here: p. 303.

- ↑ Fedor Schneider: Middle Ages to the middle of the thirteenth century. Leipzig et al. 1929, S. 171. Martin Lintzel: The Mathildenviten and the truth problem in the tradition of the Ottonenzeit. In: Archives for cultural history. Vol. 38, 1956, pp. 152-166. Carlrichard Brühl: Germany - France. The birth of two peoples. Cologne et al. 1990, p. 411ff.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Memoria, writing, symbolic communication. To reevaluate the 10th century. In: Christoph Dartmann, Thomas Scharff, Christoph Friedrich Weber (eds.): Between pragmatics and performance. Dimensions of medieval writing culture. Turnhout 2011, pp. 85–101, here: p. 95.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: pp. 406-410 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: pp. 406-410 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: p. 410 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: p. 420 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: p. 411 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: p. 394 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: pp. 430f. ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: p. 440 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Widukinds report on the Aachen election and coronation of Otto I. In: Early medieval studies. Vol. 29, 1995, pp. 390-453, here: pp. 445f. ( online ).

- ^ Hartmut Hoffmann: Ottonian questions. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages. Vol. 51, 1995, pp. 53-82 ( digitized version ); Hartmut Hoffmann: On the history of Otto the great. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages, Vol. 28 (1972) pp. 42–73 ( online ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Machabaeorum pugnae. On the importance of a biblical model in Widukind's interpretation of Ottonian kingship. In: Hagen Keller, Nikolaus Staubach (ed.): Iconologia Sacra. Myth, Visual Art and Poetry in the Religious and Social History of Ancient Europe. Festschrift for Karl Hauck on his 75th birthday. Berlin et al. 1994, pp. 417-437, here: p. 421.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: The new picture of the ruler. On the change in the "representation of power" under Otto the Great. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Ottonian new beginnings. Mainz 2001, pp. 189–211, here: p. 210.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Foreword. In: Hagen Keller: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 7-10, here: p. 9.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: On the seals of the Carolingians and the Ottonians. Documents as "emblems" in communication between the king and his loyal followers. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 32, 1998, pp. 400-444 (accessed via De Gruyter Online). Hagen Keller: Ottonian rulers' seal. Observations and questions about shape and message and function in the historical context. In: Konrad Krimm, Herwig John (ed.): Image and history. Studies in political iconography. Festschrift for Hansmartin Schwarzmaier on her 65th birthday. Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 1-49; also in: Ottonische Königsherrschaft , pp. 131–166, 275–297.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: The imperial coronation of Otto the great. Conditions, events, consequences. In: Matthias Puhle (Ed.): Otto the Great. Magdeburg and Europe. Vol. 1, Mainz 2001, pp. 461-480, especially p. 468. Hagen Keller: The new image of the ruler. On the change in the "representation of power" under Otto the Great. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Ottonian new beginnings. Mainz 2001, pp. 189-211.

- ^ Hagen Keller: The portrait of Emperor Heinrich in the Regensburg Gospels from Montecassino (Bibl. Vat., Ottob. Lat. 74). At the same time a contribution to Wipo's "Tetralogus". In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 30, 1996, pp. 173-214 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ See, for example, Stefan Weinfurter: Sacred monarchy and establishment of rule at the turn of the millennium. The Emperor Otto III. and Heinrich II. in their pictures. In: Helmut Altrichter (Hrsg.): Pictures tell stories. Freiburg 1995, pp. 47-103, especially pp. 96-99.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Ritual, Symbolism and Visualization in the Culture of the Ottonian Empire. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 35, 2001, pp. 23-59 (accessed via De Gruyter Online). Gerd Althoff: The power of rituals. Symbolism and rule in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2003.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Memoria, writing, symbolic communication. To reevaluate the 10th century. In: Christoph Dartmann, Thomas Scharff, Christoph Friedrich Weber (eds.): Between pragmatics and performance. Dimensions of medieval writing culture. Turnhout 2011, pp. 85–101, here: p. 101.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 3rd, revised edition. Stuttgart et al. 2013.

- ↑ See the review by Sven Kriese zu Keller, Hagen: Ottonische Königsherrschaft. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002. In: H-Soz-Kult , October 29, 2002 ( online ).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: Foreword. In: Hagen Keller: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 7-10, here: p. 10.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: About the role of the king in the establishment of bishops in the empire of the Ottonians and Salians. Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 44, 2010, pp. 153-174 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hagen Keller: The Ottonen. Munich 2001.

- ↑ Otoni. Jindřich I. Ptáčník, Ota I., II., III., Jindřich II., Translated by Vlastimil Drbal, Prague 2004.

- ↑ Gli Ottoni. Una dinastia imperiale fra Europa e Italia (secc. X e XI) , edizione italiana a cura di Giovanni Isabella, Rome 2012.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: The time of the late Carolingians and the Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. Stuttgart 2008, p. 27. Cf. the review by Egon Boshof in: Das Historisch-Politische Buch . Vol. 56, 2008, pp. 373f.

- ↑ Gerd Tellenbach: The early and high medieval Tuscany in the historical research of the 20th century. Methods and goals. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries. Vol. 52, 1972, pp. 37-67.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Research into Italian urban communities since the middle of the 20th century. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 48, 2014, pp. 1–38, here: p. 12 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hagen Keller: The place of jurisdiction in northern Italian and Tuscan cities. Investigations into the position of the city in the ruling system of the Regnum Italicum from the 9th to the 11th century. In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries. Vol. 49, 1969, pp. 1-72, here: p. 71 ( online ).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Aristocratic rule and urban society in Northern Italy. 9th to 12th centuries. Tübingen 1979, p. 367.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Aristocratic rule and urban society in Northern Italy. 9th to 12th centuries. Tübingen 1979, p. 367.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Research into Italian urban communities since the middle of the 20th century. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 48, 2014, pp. 1–38, here: p. 21 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Research into Italian urban communities since the middle of the 20th century. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 48, 2014, pp. 1–38, here: p. 14 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Signori e vassalli nell'Italia delle città (secoli IX-XIII). Translated by Andrea Piazza, Turin 1995.

- ^ Edward Coleman: The Italian communes. Recent work and current trends. In: Journal of Medieval History. Vol. 25, 1999, pp. 373–397, here: p. 382. See also the review by Michael Matheus in: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History: German Department. Vol. 181, 1984, pp. 347f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Collaborative Research Center 231 (1986–1999): Carriers, fields, forms of pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages at the Westphalian Wilhelms University of Münster .

- ↑ Christel Meier: Introduction. In: Hagen Keller, Christel Meier, Volker Honemann, Rudolf Suntrup (eds.): Pragmatic dimensions of medieval writing culture. Files from the Münster International Colloquium May 26-29, 1999. Munich 2002, pp. XI – XIX, here: XI ( digitized version ).

- ^ Hans-Werner Goetz: Modern Medieval Studies. Status and perspectives of medieval research. Darmstadt 1999, p. 342f.

- ^ Franz Josef Worstbrock, Hagen Keller: Carriers, fields, forms of pragmatic writing. The new Collaborative Research Center 231 at the Westphalian Wilhelms University of Münster. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 22, 1988, pp. 388-409, here: p. 390 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Cf. Hagen Keller, Franz Josef Worstbrock: The Münster Collaborative Research Center 231 'Carriers, Fields, Forms of Pragmatic Writing in the Middle Ages'. Report. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 34, 2000, pp. 388-409, here: pp. 388f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Klaus Grubmüller, Nikolaus Staubach (ed.): Pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages. Appearances and stages of development. Munich 1992; Christel Meier, Dagmar Hüpper, Hagen Keller (eds.): The Codex in Use. Munich 1996; Hagen Keller, Christel Meier, Thomas Scharff (ed.): Writing and life practice in the Middle Ages. Capture, preserve, change. Munich 1999; Christel Meier, Volker Honemann, Hagen Keller, Rudolf Suntrup (eds.): Pragmatic dimensions of medieval writing culture. Files of the International Colloquium Münster May 26-29, 1999. Munich 2002.

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Franz Josef Worstbrock: The Münster Collaborative Research Center 231 'Carriers, fields, forms of pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages'. Report. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 34, 2000, pp. 388-409, here: p. 389 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Jörg W. Busch (Ed.): Statutencodices of the 13th century as witnesses of pragmatic writing. The examples from Como, Lodi, Novara, Pavia, Voghera. Munich 1991. Hagen Keller, Thomas Behrmann (Hrsg.): Communal documents in Northern Italy. Forms, functions, tradition. Munich 1995.

- ↑ The publications of the project are listed in Hagen Keller: La civiltà comunale italiana nella storiografia tedesca. In: Andrea Zorzi (ed.): La civiltà comunale italiana nella storiografia internazionale. Atti del I Convegno internazionale di studi del Centro di studi sulla civiltà comunale dell'Università degli studi di Firenze (Pistoia, 9-10 April 2005). Firenze 2008 pp. 19–64, here: pp. 60–64.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Research into Italian urban communities since the middle of the 20th century. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 48, 2014, pp. 1–38, here: p. 21 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: The change in social behavior and the writing of administration in the Italian urban communities. In: Hagen Keller, Klaus Grubmüller, Nikolaus Staubach (eds.): Pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages. Appearances and stages of development. (Files from the international colloquium, May 17-19, 1989). Munich 1992, pp. 21-36, here: p. 24 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: The change in social behavior and the writing of administration in the Italian urban communities. In: Hagen Keller, Klaus Grubmüller, Nikolaus Staubach (eds.): Pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages. Appearances and stages of development. (Files from the international colloquium, May 17-19, 1989). Munich 1992, pp. 21-36, here: pp. 25f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: The change in social behavior and the writing of administration in the Italian urban communities. In: Hagen Keller, Klaus Grubmüller, Nikolaus Staubach (eds.): Pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages. Appearances and stages of development. (Files from the international colloquium, May 17-19, 1989). Munich 1992, pp. 21–36, here: p. 26 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Northern Italian statutes as witnesses and sources for the writing process in the 12th and 13th centuries. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 22, 1988, pp. 286-314 (accessed via De Gruyter Online). Hagen Keller, Jörg W. Busch (Hrsg.): Statutencodices of the 13th Century as witnesses of pragmatic writing. The examples from Como, Lodi, Novara, Pavia, Voghera. Munich 1991. Jörg W. Busch: On the process of writing the law in Lombard communities of the 13th century. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 25, 1991, pp. 373-390 (accessed via De Gruyter Online). Peter Lütke Westhues: The municipal statutes of Verona in the 13th century. Forms and functions of law and writing in a northern Italian municipality. Frankfurt am Main et al. 1995. Hagen Keller: On the source genre of the Italian city statutes. In: Michael Stolleis , Ruth Wolff (ed.): La bellezza della città. City law and urban design in Italy in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Tübingen 2004, pp. 29-46.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Northern Italian statutes as witnesses and sources for the writing process in the 12th and 13th centuries. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 22, 1988, pp. 286-314 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: The change in social behavior and the writing of administration in the Italian urban communities. In: Hagen Keller, Klaus Grubmüller, Nikolaus Staubach (eds.): Pragmatic writing in the Middle Ages. Forms and stages of development, files of the International Colloquium 17. – 19. May 1989. Munich 1992, pp. 21-36. Hagen Keller: Changes in the rural economy and life in Northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries. Population growth and social organization in the European High Middle Ages. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 25, 1991, pp. 340-372, here: p. 357 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Changes in the rural economy and life in northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries. Population growth and social organization in the European High Middle Ages. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 25, 1991, pp. 340-372, here: p. 364 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Changes in the rural economy and life in northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries. Population growth and social organization in the European High Middle Ages. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 25, 1991, pp. 340-372, here: p. 362 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Changes in the rural economy and life in northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries. Population growth and social organization in the European High Middle Ages. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 25, 1991, pp. 340-372, here: p. 366 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Petra Koch: Municipal books in Italy and the beginning of their archiving. In: Hagen Keller, Christel Meier (Ed.): The Codex in Use. Files of the International Colloquium 11. – 13. June 1992. Munich 1996, pp. 87-100. Petra Koch: The archiving of municipal books in the northern and central Italian cities in the 13th and early 14th centuries. In: Hagen Keller, Thomas Behrmann (Hrsg.): Municipal documents in Northern Italy. Münster 1995, pp. 19-69.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Changes in the rural economy and life in northern Italy during the 12th and 13th centuries. Population growth and social organization in the European High Middle Ages. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 25, 1991, pp. 340-372 (accessed via De Gruyter Online). Thomas Scharff: Capture and frighten. Functions of the process documents of the ecclesiastical inquisition in Italy in the 13th and early 14th centuries. In: Susanne Lepsius, Thomas Wetzstein (ed.): When the world came into the files. Litigation documents in the European Middle Ages. Frankfurt am Main 2008, pp. 254-273. Thomas Scharff: Font for control - control of the font. Italian and French inquisitorial manuals of the 13th and early 14th centuries. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages . Vol. 52, 1996, pp. 547-584 ( digitized version ). Thomas Lentes, Thomas Scharff: Writing and Discipline. The examples of the inquisition and piety. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 31, 1997, pp. 233-251.

- ↑ Thomas Scharff: Capture and Scare. Functions of the process documents of the ecclesiastical inquisition in Italy in the 13th and early 14th centuries. In: Susanne Lepsius, Thomas Wetzstein (ed.): When the world came into the files. Litigation documents in the European Middle Ages. Frankfurt am Main 2008, pp. 254–273, here: p. 256.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: About the connection between writing, cognitive orientation and individualization. On the behavior of Italian citizens in the Duecento. In: Hagen Keller, Christel Meier, Volker Honemann, Rudolf Suntrup (eds.): Pragmatic dimensions of medieval writing culture. Files from the Münster International Colloquium May 26-29, 1999. Munich 2002, pp. 1–22, here: p. 1 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Aaron J. Gurjewitsch : The individual in the European Middle Ages. Munich 1994, pp. 9-31.