Stefan Weinfurter

Stefan Weinfurter (born June 24, 1945 in Prachatitz / Böhmen ; † August 27, 2018 in Mainz ) was a German historian who researched the history of the early and high Middle Ages .

Weinfurter held chairs for Medieval History at the Universities of Eichstätt (1982–1987), Mainz (1987–1994), Munich (1994–1999) and Heidelberg (1999–2013). His books about the two holy emperors of the Middle Ages, Charlemagne and Henry II , about the empire in the Middle Ages or about Canossa were widely circulated. He introduced the term “order configurations”, which describes the coexistence and opposition of medieval orders, into the mediaeval discussion. From the 1990s he and Bernd Schneidmüller played a leading role in almost all of the major medieval exhibitions in Germany. The major exhibition in Speyer in 1992 and numerous publications made him one of the best experts on the Salier era .

Life

Stefan Weinfurter was born in 1945 as the son of the teacher Julius Weinfurter and his wife Renata, née Lumbe Edle von Mallonitz (1922–2008), who came from a family of lawyers in Prachatitz, South Bohemia. The maternal ancestor Josef Thaddeus Lumbe von Mallonitz was ennobled in 1867. Weinfurter's father was drafted into military service during the Second World War and was taken prisoner by the Americans. He died on May 8, 1945, the day the German Wehrmacht surrendered , in the Büderich POW camp . After being expelled from Czechoslovakia in February 1946, Weinfurter grew up with his mother in Hechendorf am Pilsensee , then from 1958 in Munich and Geretsried . The bohemian origin and the family reintegration left a lasting impression on Weinfurter.

He passed his Abitur in July 1966 at the Karlsgymnasium in Munich . Then Stefan Weinfurter studied physics for one semester at the TH Munich in 1966/67 . He then began studying history, German and educational science at the University of Munich in the 1967 summer semester, which he completed in the 1971 summer semester. He took the proseminar in medieval history with Johannes Spörl , where he became a student assistant after completing the proseminar on Charles IV . In 1970 Weinfurter passed the state examination in Munich. From the winter semester 1971/72 to the winter semester 1972/73 he studied history and German at the University of Cologne . In 1971/72 he worked there at Odilo Engels . In this Weinfurter was in the summer semester 1973 with a thesis on the Salzburg diocese and Bishop reform policy in the 12th century doctorate . From 1973 to 1974 he worked as a research assistant at the University of Cologne, from 1974 to 1981 as an academic councilor. Weinfurter gave up the originally planned habilitation project on the history of the Duchy of Bavaria in the early and high Middle Ages. Instead, in 1980 he completed his habilitation in Cologne with an annotated edition of the order of life of a Limburg monastery of the regulated Augustinian canons from the 12th century. In 1981/82 he represented the professorship for Medieval History at the University of Heidelberg, which had become vacant due to the death of Peter Classen .

In 1982, at the age of 36, he was appointed to the newly founded Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt . There he taught until 1987 as a professor of regional history with a special focus on Bavaria. The family found their new home in Gaimersheim . He gave his inaugural lecture in Eichstätt in November 1983 on the history of Eichstätt in Ottonian - Salian times. During this time he deepened approaches to regional history and expanded his medieval teaching profile into Bavarian contemporary and economic history. Almost every year during this time he published an essay on the history of the bishops of Eichstätt from the beginnings, the work of St. Willibald von Eichstätt in the 8th century, to the 14th century. Over the course of several years, an edition of episcopal chronicles ( Gesta episcoporum ) was created in collaboration with students . Intensive construction activity began in Eichstätt in the 1980s. The deep interventions in the historic city center exposed unique archaeological material. The sites and the evaluation possibilities of the digging neighboring discipline aroused his interest. Weinfurters worked closely with representatives of building history and urban archeology . From 1985 to 1987 he was Dean of the Faculty of History and Social Sciences in Eichstätt . As dean, he organized the relocation of the locations across the city to the buildings in Universitätsallee, which were gradually ready for occupancy from 1986 onwards. Between 2007 and 2011 he was a member of the University Council of Eichstätter University.

In 1987, Weinfurter accepted an appointment at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz . As the successor of Alfons Becker , he taught medieval history and historical auxiliary sciences there until 1994 . During this time, his work focused on the Salian ruling dynasty of the 11th century and thus on the kingship of the German High Middle Ages . Since he played a key role in the organization of the large Salier exhibition in Speyer, teaching history also became one of his most important fields of activity. In 1993, he turned down a call to Cologne to succeed his academic teacher Engels as professor of medieval history. From 1994 to 1999 he taught as the successor to Eduard Hlawitschka as professor for medieval history at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . In 1996 he organized the German Historians' Day "History as an Argument" in Munich . During his time in Munich, people became the focus of his research. Weinfurter increasingly used image sources in his research. In 1999 he published a biography of Heinrich II. This was followed by books and numerous essays on the Salier period, the Hohenstaufen , the journey to Canossa and the medieval history of the empire.

In autumn 1999 he was appointed to succeed Hermann Jakobs as professor for medieval history and historical auxiliary sciences at the University of Heidelberg. An important reason for accepting the call was the proximity to his family in Mainz. He gave his inaugural lecture in Heidelberg in June 2000 on order configurations using the example of Heinrich III. In Heidelberg, Weinfurter's main focus was on rituals and cultural encounters during the crusades . Weinfurter's move to Heidelberg came at a time when collaborative research was becoming increasingly important as a funding instrument for the German Research Foundation. Together with Schneidmüller, Weinfurter was able to successfully use the new funding opportunities for Heidelberg. This created a wide range of opportunities for young scientists. As a result, Heidelberg developed into an important center for research on the Middle Ages during these years. At Heidelberg University, Weinfurter was a member and sub-project leader in the Collaborative Research Centers 619 “Ritual Dynamics” (until 2013) and “Material Text Cultures” (2009–2013). In addition, he led a sub-project in the DFG priority program 1173 “Integration and Disintegration of Cultures in the European Middle Ages” (2005–2011). Together with Gert Melville and Bernd Schneidmüller, he led the Heidelberg academy project “Monasteries in the High Middle Ages. Innovation laboratories of European life plans and models of order ”. From 2004 to 2006 Weinfurter was Dean of the Philosophical Faculty in Heidelberg. From 1999 to 2013 he was director of the Institute for Franconian-Palatinate History and Regional Studies in Heidelberg. On the occasion of his 65th birthday, a conference took place in Heidelberg from June 23rd to 25th, 2010, the contributions of which were published in 2013. Most of the individual studies deal with the development of political order and its conceptualization in the 13th century. He retired in Heidelberg in 2013 . 16 dissertations were completed under Weinfurter's supervision as an academic teacher. His most important academic students included Stefan Burkhardt , Jürgen Dendorfer , Jan Keupp and Thomas Wetzstein . From January 2013 Weinfurter was head of the Research Center for History and Cultural Heritage (FGKE) in the Villa Poensgen in Heidelberg and from September 1, 2013 he was senior professor at the University of Heidelberg.

Weinfurter was married from 1970. He stayed in Mainz while teaching in Munich and Heidelberg. He was particularly fascinated by the cities and imperial cathedrals in Speyer, Worms and Mainz. He died of heart failure on August 27, 2018 at the age of 73 at home in Mainz. He left a wife, three daughters and seven grandchildren.

Research priorities

Weinfurter published over 200 publications between 1974 and his death in 2018. His research dealt with the history of the empire and rule in the Ottonian, Salian and Staufer times, configurations of order in a European context, rituals and communication in politics and society, regional and church history in the Middle Ages and early modern times, the history of orders in the high Middle Ages and images as historical sources. In the mid-1990s, there was close collaboration in Weinfurter's research with Bernd Schneidmüller. With his academic teacher Odilo Engels , he edited four volumes of the series episcoporum ecclesiae catholicae occidentalis (1982, 1984, 1991, 1992), a prosopography of the early and high medieval bishops. In 1982 Weinfurter gave a programmatic overview of the problems and possibilities of prosopography of the early and high medieval episcopate at the first interdisciplinary conference on medieval prosopography in Bielefeld. The wide-ranging spatial and temporal objectives, among other things, proved to be particularly difficult.

22 essays by Weinfuer published between 1976 and 2002 were bundled in an anthology in 2005 on the occasion of his 60th birthday. The editors had selected these essays because they present Weinfurter's “explanatory model of the reality of order and the concept of order in a condensed form [...]”.

Church and canon reform in the 11th and 12th centuries

His first work was devoted to the regular canons . His dissertation, published in 1975, dealt with the spiritual new beginning in Salzburg. He wanted to work out "the characteristic development, shape and significance of individual reform groups" using the example of the Salzburg church province. The main initiator of the reform movement has long been the Archbishop of Salzburg, Konrad I. According to Weinfurter, Konrad's first reform measures can be dated before his return from exile in Saxony (1121), in Reichersberg and Maria Saal . Konrad intended not only a clerical reform, "but a complete reorganization of the diocese, characterized by a new system of relations, which should determine the ecclesiastical constitution in this district".

Weinfurter illuminated the self-image of the reform canons in a prologue to the Rule of Augustine written in the Salzburg region in the 12th century . Weinfurter researched the Premonstratensians intensively with particular emphasis on Norbert von Xanten .

Biographies on Henry II and Charlemagne

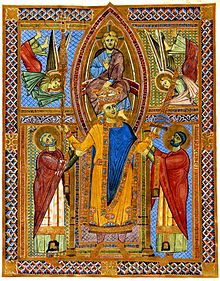

Miniature from the sacramentary of Heinrich II, today in the Bavarian State Library in Munich (Clm 4456, fol. 11r)

The starting point for many years of preoccupation with Heinrich II was the study published in 1986 on the centralization of power in the empire by Emperor Heinrich II. The contribution was Weinfurter's colloquium lecture as part of his habilitation process in Cologne. Heinrich II often compared previous research with his predecessor Otto III. examined. Weinfurter, on the other hand, saw in Heinrich's concept of rule "to a high degree a continuation and enhancement of the elements developed in the ducal rule on the royal level". The study, which comprised almost 60 pages, was methodologically innovative not only because it linked the history of the state and the empire, but also because in the 1980s it marked the beginning of the return to a preoccupation in medieval research with the individuals involved. The Bamberg conference organized with Bernd Schneidmüller in June 1996 on the continuities and discontinuities in the reign of Otto III proved to be particularly fruitful for his biography . and Heinrichs II. Weinfurter published the articles together with Schneidmüller in 1997. The presentation was also the first volume of a new series of publications ( Medieval Research ) published by Schneidmüller and Weinfurter , which aims to "take up innovative questions in modern media studies in their full breadth and, if possible, interest a broader audience". His account of Heinrich II, published in 1999, was the first comprehensive biography since the "Yearbooks of German History" by Siegfried Hirsch and Harry Bresslau (1862/75). The work is not structured chronologically, but deals with the following aspects in individual chapters: Imperial structure, the idea of a king, marriage / childlessness, court and counselor, relationship to the imperial church , monastery policy, conflicts with the great , external relations to the east and west, Italy and the empire as well as Bamberg . In his biography, Stefan Weinfurter particularly emphasized the increased end-time expectation and the biblical leading figure Moses for Heinrich's reign. He explained the long-standing conflicts with the Polish King Bolesław Chrobry with similar views of power, since both saw themselves chosen by God to convey the divine commandments to their people and they wanted to align their entire rule to these commandments. In this context, he also accorded great importance to images as historical sources. According to his research, the Regensburg sacramentary played a special role. Weinfurter understood the image as an expression of the king's increased claim to sacred legitimacy beyond the political power structure. It was from this picture in particular that Weinfurter derived a special "royal idea" that was linked to Moses. According to Ludger Körntgen , this claim appears problematic, since the Old Testament does not depict Moses as a royal figure. In Pericopes Heinrichs II. Visualized by Weinfurter "permission of Henry's claim to royalty". Unlike Hagen Keller , Weinfurter tends to refer to the image of the ruler Heinrich II and not Heinrich III in the Montecassino Gospel Book. to see. Weinfurter justified this, among other things, with the fact that, following the tradition of Montecassino, Emperor Heinrich II gave the monastery a valuable gospel book . About Heinrich III. no information has been passed on in this regard.

Weinfurter contradicted Ludger Körntgen with regard to the conflict behavior and the individuality of the ruler Heinrich II. Körntgen assumed an "interplay of 'rule and conflict' which should have determined the Ottonian-Early Sali epoch beyond the individual possibilities of various rulers". According to Weinfurter, however, Heinrich's behavior “can only be explained from his very individual idea of the legitimation, task and function of his kingship based on his ruler personality”. For the anniversary year 2002 Weinfurter dealt in an essay about the origins and personal environment of Kunigunde , Heinrich's wife. Weinfurter attached great importance to their coronation on August 10, 1002 in Paderborn, on the one hand as a "signal for the Saxons" through the choice of the coronation location Paderborn, and on the other hand as the first independent queen coronation. Kunigunde acted "in almost complete, harmonious harmony with the goals and ideas of her husband".

On the occasion of the Charlemagne anniversary in 2014, Weinfurter published a biography of Charlemagne . Until then, Weinfurter had hardly emerged through his own work on the Carolingian era. The biography was translated into Italian in 2015. After an overview of the sources and the early Carolingians, Weinfurter treated Karl's reign not chronologically, but systematically according to levels of action (wars, domestic politics, family, educational reform, church politics and empire). Weinfurter identified a “major project of disambiguation” and a “Christianization of the state” as the guiding principles for Charlemagne's actions. With his thesis of “disambiguation”, which runs through all twelve chapters of the presentation, Weinfurter means “the interpretative sovereignty in religious and moral behavior”, “the clarity of language, argumentation and temporal order” as well as “political, military and ecclesiastical Organization". Karl's constant striving for clarity is in contrast to the vagueness or ambiguity in our society today.

State and church history

Eichstätter diocese history

At the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, Weinfurter published several articles on the medieval history of the diocese of Eichstatt and thus gave new impetus to the long-fallow field of research on the history of bishops. In 1987, based on the only surviving medieval manuscript (Diözesanarchiv Eichstätt, MS 18) from the end of the 15th century, he presented an edition of the history of the Eichstätt bishops by Anonymous Haserensis . Until then, the most important work on the history of the Eichstätt diocese of the early and high Middle Ages was only accessible in the MGH edition (MGH SS 7, pp. 254–266) by Ludwig Konrad Bethmann (1784–1867) from 1846. Weinfurter's revision facilitates access to a much-used work. Together with Harald Dickerhof , he organized a conference in Eichstätt in the summer of 1987 on the 1200th anniversary of the death of St. Willibald , the contributions of which were published in 1990. Weinfurter himself discussed the three approaches for the creation of the diocese. He rejected the early approach to 741 and, together with Dickerhoff, decided on the years 751/52 as the founding date for the diocese. In 2010, a volume on the medieval history of the Eichstatt diocese was published, which bundles six contributions by Weinfurter from 1987–1992.

Mainz, Speyer and Lorsch

In close connection with his research on the Salians, Weinfurter published several studies dealing with Speyer and the cathedral there . Weinfurter also devoted himself to Mainz and Lorsch . So he investigated the dissolution of the Benedictine monastery Lorsch in the late Staufer period. The downfall of the monastery is justified by Pope Innocent IV and the Archbishop of Mainz Siegfried II with the moral decline of the monks. According to Weinfurter's source analysis, the power struggle between the Archbishop of Mainz and the Count Palatine was more decisive. Politically, the Archbishop of Mainz pushed the downfall of the monastery in the winter of 1226/27 through the rebellion of the Lorsch ministerials on the Starkenburg against their abbot. In recent years he has devoted himself above all to the Carolingian Lorsch and his monastery library. Together with Bernd Schneidmüller, Weinfurter institutionalized the cooperation between the Institute for Franconian-Palatinate History and Regional Studies and the Lorsch World Heritage Site in 2005. As part of the Collaborative Research Center 933 “Material Text Cultures” and in cooperation with the Heidelberg University Library , a conference was held in 2012 at Lorsch Abbey. The handling of knowledge in the Carolingian Lorsch was examined. Weinfurter was co-editor of the results of this anthology, which appeared in 2015.

In the field of Mainz history, Weinfurter dealt, for example, with the background to the murder of Archbishop Arnold of Mainz . As the author of the archbishop's vita, he identified Gernold, Arnold's chaplain and notary. In another essay, based on linguistic parallels, he came to the conclusion that the Vita Arnoldi , a letter from Archbishop Arnold to Wibald von Stablo from the spring of 1155 and the mandate of Emperor Friedrich I (DFI 289) have the same author - i.e. Gernot. Weinfurter saw the conflict between the citizens of Mainz and their archbishop as a result of Arnold's understanding of the law. The archbishop was strictly guided by standardized law and rejected a compromise. In 2014, Weinfurter's pupil Stefan Burkhardt presented the Vita Arnoldi archiepiscopi Moguntinensis (The biography of Archbishop of Mainz Arnold von Selenhofen) in a new, commented edition with translation. This made one of the most important sources on the history of the high medieval Middle Rhine area accessible to the public. Burkhardt comes to the same conclusion as Weinfurter that the chaplain Gernot must have written the text immediately after the archbishop's murder. Also in 2014 Weinfurter published an article about Arnold von Selenhofen's vita and memoria .

Salierzeit

Weinfurter is also considered a particular expert on the Salier period , which he recognized in his research as a special period of upheaval and threshold. From 1988 to 1991 he was in charge of the development and editing of historical publications for the large exhibition "The Salians and their Empire" organized by the State of Rhineland-Palatinate in Speyer . Under Weinfuer's direction, 48 authors could be won for collaboration. Weinfurter published their results in three academic volumes in 1991. In 1991 he published the illustration Reign and Empire of the Salians. Basics of a time of upheaval translated into English by Barbara Bowlus in America in 1999. In Trier in September 1991 he organized a conference on reform ideas and reform policy in the late Salian and early Staufer times. The articles appeared a year later. He laid a fundamental reassessment of the Salian Emperor Henry V before. According to his argument, religious reform motives of the conspirators and less power-political interests were the motives of Heinrich V for the disempowerment of his father Heinrich IV. Heinrich was only able to secure the succession through an alliance with these reform forces.

900 years after the death of Emperor Heinrich IV, a symposium was held in May 2006 by the "European Foundation for the Imperial Cathedral of Speyer" at his burial site in Speyer. The conference proceedings Salisches Kaisertum and neue Europa , edited by Weinfurter and Bernd Schneidmüller in 2007, brings together 18 contributions. A emphatically European perspective aims to overcome the imperial-centered interpretation of “an old German topic” and achieve a new understanding based on European levels of comparison. In his summary of the results, Weinfurter emphasized the "increase in efficiency in all areas". In 2004 Weinfurter published Das Jahrhundert der Salier. (1024–1125) a presentation that was aimed at a wider audience.

Order configurations in the Middle Ages

Weinfurter coined the term "order configurations" for the 11th century, which describes the coexistence and opposition of medieval orders. In 1998 he organized a conference in Cologne on the subject of Stauferreich in transition. Concepts of order and politics before and after Venice (1177). The starting point was the question of whether there was a relevant change in the political and conceptual configurations of the empire in the time of Frederick I and what role the events during the Peace of Venice played in this. In this context, Weinfurter used the phrase “power and notions of order in the high Middle Ages” for the first time. In 2001 he treated the time of Henry III in the treatise "Configurations of Order in Conflict". During the time of the emperor, “the configurations of order entered into such fierce competition with one another that the power of integration of the sacred ruler was broken - forever.” His “rule simultaneously ushered in the decline of a configuration of order in which the religious commandment was entirely on the king was centered and formed the basis of royalty. ”Together with Bernd Schneidmüller , he organized a Reichenau conference of the Constance working group for medieval history on“ order configurations ” in autumn 2003 . With this conference a “research design” was tested in the scientific discussion. The aim was to remove the traditional constitutional concept of medieval studies from its statics. “Configurations of order” were defined as the “interrelationship between imaginary and established order”. Weinfurter recognized a "significant turning point" in the conflict between Heinrich IV. And Heinrich V, as a changed social order became visible.

For Weinfurter, in a contribution published in 2002, the failure of the negotiations between Henry V and Pope Paschal II in 1111 and the Peace of Venice in 1177 were turning points in history. Under Henry V "the reform-religious community of responsibility of king and prince broke up". With the Peace of Venice, the imperial authority suffered a serious setback. Weinfurter concluded that on both occasions the configurations of order tapering towards the authority of the ruler were so weakened that the connection with the development of the monarchies in Europe was finally broken. In the future, Germany had embarked on the path to the federal system.

Imperial history

Weinfurter published several essays that are repeatedly devoted to the evaluation of individuals who are important for the empire. In 1993 he and Hanna Vollrath published 23 articles in a commemorative publication for Odilo Engels on his 65th birthday about the city and the diocese of Cologne in the Middle Ages. For Weinfurter, Archbishop Philipp of Cologne was the driving force behind the feudal proceedings against Henry the Lion . As a result, further research also changed the perception of Friedrich Barbarossa when Henry the Lion fell. The fall of the lion is no longer judged to be the result of a single-minded plan pursued by Barbarossa, but rather the emperor appears as the “driven” of the princes when Heinrich is deposed. In 1999, in the 1000th year of Adelheid's death of Burgundy , Weinfurter published a study on Otto the Great's wife and gave her great importance. For him Adelheid “played a unique key role for the Ottonian empire and appears to be the decisive figure in conveying the Italic-imperial traditions to the Sachsenhof”.

With Schneidmüller, Weinfurter published an anthology in 2003 on the German rulers of the Middle Ages. The work contains 28 short biographical descriptions from Heinrich I to Maximilian I and thus provides an overview of the medieval history of the empire. Weinfurter wrote the contributions to Otto III. and Heinrich II. In 2006 he published a book about the causes and consequences of the penitential walk to Canossa . In eleven chapters he described the development that began with the reign of Henry III. and ends with the Worms Concordat . Weinfurter interpreted the investiture controversy as the beginning of a process of secularization "in which the unity of religious and state order dissolves". In 2008 a presentation about the medieval history of the empire was published. Weinfurter focused on the political development from the founding of the Franconian Empire to Emperor Maximilian I. He also considered social, economic, legal and constitutional aspects.

In 2002 Weinfurter published the contributions to a conference in honor of Odilo Engels from April 30th to May 2nd, 1998. They deal with the time of Friedrich Barbarossa and the political conceptions of that time. In his introduction he asked whether the Peace of Venice had marked a turning point in the Barbarossa era. Weinfurter came to the conclusion that the peace treaty not only changed the empire, but also opened the empire in favor of small territorial units. In April 2008, on the occasion of Odilo Engels' 80th birthday, a conference took place at the University of Düsseldorf, the contributions of which Weinfurter published in 2012. The individual studies deal with papal history from the 8th to the 13th century with a clear focus on the 11th and 12th centuries.

In a contribution published in 2005, Weinfurter dealt with the question of how it came about that the Roman-German Empire was viewed as "holy". Based on the formulation sacro imperio et divae rei publicae consulere from a document by Barbarossa from 1157, he followed the development of the imperial idea under Emperor Friedrich I. During his time, he only recognized rather vague transpersonal concepts of the state. On the linguistic level, regnum was not clearly recognized as an institution until the 12th century. Weinfurter saw the explanation for the expression in the fact that "one began to think of the empire in the correspondence of the sancta ecclesia , the holy church, as an institution". He identified the learned abbot Wibald von Stablo as the mediator of this idea of the “holy” emperor and empire. The reason for the effort could be the equivalence of the “holy” empire with Byzantium and even more so with the papal church in Rome. Weinfurter and Schneidmüller published an anthology in 2006 on the 200th anniversary of the end of the Old Kingdom. This bundles contributions from leading experts in medieval studies on the Holy Roman Empire and its position within Europe. Weinfurter contributed a contribution to the anthology about the ideas and realities of the empire of the Middle Ages .

Rituals and Communication in Politics and Society

Weinfurter's other focal points of research included rituals and communication in politics and society, the formation of political will and forms of their symbolism and presentation. In May 2008 in Speyer, together with Bernd Schneidmüller and Wojciech Falkowski, he organized a scientific conference on the ritualization of political decision-making in the high and late Middle Ages in comparison between Poland and Germany. The focus of the contributions by Polish and German Medievalists were processes of decision-making and strategies for their implementation in political communication. The anthology with 16 articles was published in 2010.

The Collaborative Research Center “Ritual Dynamics” (SFB 619) at Heidelberg University, funded by the German Research Foundation, examined rituals and their changes and dynamics from 2002 to 2013. Together with Schneidmüller, Weinfurter led the sub-project B8 “Ritualization of Political Will-Formation in the Middle Ages”. In 2005, together with Marion Steinicke, he edited the contributions to a conference on the establishment of power and its rituals held in October 2003 as part of the SFB Ritualdynamik. The contributions extend from the Greek polis to the end of the 20th century. For Weinfurter, the divestment of Heinrich the Lion in 1181 was the starting point for his reflections on the changeability of the investiture ritual. For the first time, a ruler could no longer exercise his right of grace, which would have allowed him to reinvest Heinrich the Lion with imperial fiefs. Weinfurter stated that the “God-related order system of grace” effective from the Ottonian-Salian period was increasingly supplanted by law as the new standard of order in the investiture ritual in the course of the 12th century. As a further result of the SFB, Weinfurter was co-editor of an anthology published in 2005 with 40 short articles on rituals from antiquity to the present. Based on the description in Thietmar's Chronicle of Merseburg , Weinfurter dealt with King Heinrich II's ritual of humility at the Frankfurt Synod . By repeated prostration before the 28 assembled bishops, Heinrich succeeded in establishing the diocese of Bamberg . In the same volume he dealt with the submission ( deditio ) of Duke Heinrich of Carinthia and his army in 1122 under the power of Archbishop Konrad of Salzburg . Weinfurter also examined the punishment of carrying dogs using the works of Otto von Freising , Widukind von Corvey , Wipo and the vita of Archbishop Arnold von Mainz. Weinfurter illustrated in his study The Pope Weeps , published in 2010 , how Pope Innocent IV repeatedly wept loudly and publicly at the Council of Lyon in 1245 when Emperor Frederick II was deposed , in order to emphasize the inevitability of his actions.

Implementation of historical research in large exhibitions and television

Furthermore, Weinfurter was also active in organizing science. The communication of history in exhibitions and the media has been a focus of Weinfurter's work for many years. With Bernd Schneidmüller and in close cooperation with Alfried Wieczorek and the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museum in Mannheim, but also with the Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg and the Historisches Museum der Pfalz in Speyer, he played a key role in the conception and implementation of scientific conferences and major medieval exhibitions. These included " Otto the Great " (2001 in Magdeburg ), "Emperor Heinrich II." (2002 in Bamberg ), "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. From Otto the Great to the End of the Middle Ages ”(2006 in Magdeburg),“ The Staufers and Italy ”(2010/11 in Mannheim ),“ The Wittelsbachers on the Rhine. The Electoral Palatinate and Europe "(2013/2014 in Mannheim) or" The Popes and the Unity of the Latin World "(2017 in Mannheim).

In preparation for a major exhibition, a scientific conference was held, the results of which were documented in an accompanying publication. As a scientific preparation for the 27th exhibition of the Council of Europe and the state of Saxony-Anhalt ("Otto the Great, Magdeburg and Europe"), a colloquium was held in Magdeburg in May 1999 under the heading of "New Ottonian Beginnings". Weinfurter and Schneidmüller published the articles in 2001. According to the editor's foreword, the subject of debate was the transformation process of the 10th century between change and continuity from (East) Franconian to German history. The focus was on Otto the Great . Weinfurter introduced the proceedings with his contribution. He highlighted the indivisibility of rule, the sacralization of kingship and the recourse to the imperial idea as defining moments of Otto's rule. For the Magdeburg exhibition "Otto the Great, Magdeburg and Europe", he published two important volumes in 2001 with Bernd Schneidmüller and Matthias Puhle , which together comprise over 1200 pages. The first volume contains 37 essays in six chapters. In the second volume, the exhibits are presented and rated by well over 50 scientists. The Bavarian State Exhibition took place from July 9th to October 20th, 2002 in Bamberg for the millennial accession of Heinrich II . Together with Josef Kirmeier and Bernd Schneidmüller, Weinfurter was one of the editors of the volume accompanying the exhibition.

Weinfurter published an anthology on Saladin and the Crusaders in 2005 with Heinz Gaube and again Schneidmüller . The volume bundles the results of a Mannheim conference in preparation for the Saladin exhibition, which the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums in Mannheim organized in partnership with the State Museum for Nature and Man in Oldenburg and the State Museum for Prehistory (Halle) . In 2004 an international conference was held in the Kulturhistorisches Museum Magdeburg in connection with the 29th exhibition of the Council of Europe and Saxony-Anhalt's state exhibition "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation 962 to 1806. From Otto the Great to the End of the Middle Ages", planned for autumn 2006 . Schneidmüller and Weinfurter published the articles in 2006. The editors wanted to turn away from a traditional chronological structure according to dynasties by attempting to combine classical political history with approaches to the history of mentality and perception. Together with Bernd Schneidmüller and Alfried Wieczorek, Weinfurter was the editor of the results of an international conference that took place in autumn 2008 in the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums in Mannheim. The conference dealt with "the interaction between the imperial ruler's authority of the Hohenstaufen on the one hand and the 'configurations of order' and the creative power of certain regions in the Hohenstaufen Empire on the other."

In May 2010, in advance of the Magdeburg exhibition, Otto the Great and the Roman Empire. The empire held a conference from antiquity to the Middle Ages . Weinfurter published the articles with Hartmut Leppin and Bernd Schneidmüller in 2012. The focus of the volume is on the Roman Empire in the first millennium. For the exhibition “Die Staufer and Italy” of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums in Mannheim, which lasted from September 19, 2010 to February 20, 2011, two extensive volumes were published by Weinfurter, Bernd Schneidmüller and Alfried Wieczorek. The first volume bundles 43 scientific “essays” and the second volume contains the exhibits. With the state on the Upper Rhine , Upper Italy with its municipalities and the Kingdom of Sicily , three innovation regions were the focus of interest. In particular, transfer processes and cultural developments are particularly taken into account. Weinfurter summarized “Competing concepts of power and notions of order in the Staufer realms north and south of the Alps”.

In preparation for the exhibition of the Mannheim Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums on the topic “The Wittelsbachers on the Rhine. The Electoral Palatinate and Europe ”(2013/2014) a scientific conference was held in January 2012. The occasion was the 800th anniversary of the award of the Palatinate Countess near Rhine by the Staufer Friedrich II. To Duke Ludwig I of Bavaria . The articles deal with the scope of action of the Wittelsbachers and their rule in the Palatinate and cover the period from 1200 to the end of the Landshut War of Succession in 1504/05. Together with Schneidmüller, Jörg Peltzer and Alfried Wieczorek, Weinfurter gave the twenty contributions to the Mannheim conference in the anthology The Wittelsbachers and the Electoral Palatinate in the Middle Ages. A success-story? Out in 2013. Weinfurter himself wrote a contribution to the Staufer foundations of the Palatinate County near the Rhine. He went into the continuities from the Lorraine to the Palatinate rule and followed the successful expansion under Konrad von Staufen since 1156. According to Weinfurter, Heidelberg was already a central place of the Palatine rule in the middle of the 12th century and not only after the death of Konrad from Staufen (1195). On the occasion of the upcoming exhibition “The Popes and the Unity of the Latin World”, a conference was held in April 2016 in the Reiss-Engelhorn Museums in Mannheim. Weinfurter published the anthology together with Volker Leppin , Christoph Strohm , Hubert Wolf and Alfried Wieczorek in 2017. Weinfurter had prepared the exhibition “The Popes and the Unity of the Latin World” for five years. She presented valuable objects from 1500 years of papal history.

In April 2018, Weinfurter and Schneidmüller led the fourth scientific symposium on "King Rudolf I and the Rise of the House of Habsburg in the Middle Ages" for the European Foundation for the Imperial Cathedral of Speyer . Weinfurter's last project before his death was the work on the major state exhibition of the General Directorate for Cultural Heritage Rhineland-Palatinate “The emperors and the pillars of their power. From Charlemagne to Friedrich Barbarossa ”, which will open in September 2020.

In television or radio broadcasts, he tried to bring the Middle Ages closer to a wider audience. Weinfurter worked on the historical documentary series “ The Germans ” as a scientific consultant for ZDF and also appeared as an expert in the documentation for the three medieval episodes (Otto the Great; Heinrich IV., Barbarossa and Heinrich the Lion). The documentary series became one of the most successful ZDF productions in this segment, with a market share of twenty percent and six million viewers when it was first broadcast. He read his book Canossa - The Disenchantment of the World as an audio book.

Memberships and scientific organizational activities

Weinfurter became a member of the Constance Working Group for Medieval History in April 1998 and was its chairman from 2001 to 2007. When he took office as chairman, the financial support from state funds and thus the existence of the working group was acutely endangered. With his professional expertise and his power of persuasion, Weinfurter succeeded in regaining the support of the ministry and thus ensuring the continued existence of the working group. With the exception of Traute Endemann , the working group consisted only of men. As chairman, he significantly rejuvenated the members and opened the working group to female scholars. Ten new members with an average age of 45 years, including three female professors for the first time, were accepted into the working group. In 2001, as chairman, he edited an anthology for the 50th anniversary of the Konstanz working group. In an essay in 2005 he also examined the Konstanz working group as reflected in its conferences. He did not rely on his own memories, but primarily on the minutes of the working group. In his remarks, he paid particular tribute to František Graus , who had developed important findings and new approaches in the Konstanz working group in the last third of the 20th century, but was viewed as a scientific outsider in the working group itself.

Weinfurter became a member of the Society for Rhenish History (1982), the Society for Franconian History (1986), the Historical Commission for Nassau (1991), the Sudeten German Academy of Sciences and Arts (1992), a member of the Commission for Historical Regional Studies in Baden- Württemberg (2000, on the board since 2006), full member of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences (2003) and corresponding member of the philosophical-historical class abroad of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (2015). From 1999 to 2008 he was an expert reviewer for medieval history at the German Research Foundation and from 2000 to 2004 he was deputy chairman of the Association of Historians in Germany . Weinfurter was also a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the German Historical Institute in Rome (2003–2011) and from 2008 to 2011 its chairman.

Scientific aftermath

According to Jörg Peltzer , the enforcement of the papal claim to represent Christ on earth alone, the resulting changes in the sacred character of the empire and the strengthening of the princely self-image as the bearer of the empire are three developments shaped by Weinfurter of long-term importance.

The concept of “order configurations”, which describes the interrelationship of lived and imagined order, was deliberately kept open and was filled with different things by research in the period that followed. This is probably why the term has not yet caught on in the field.

The current picture in historical studies of the East Franconian-German ruler Heinrich II is determined by Weinfurter's biography published in 1999 and his accompanying studies.

Fonts (selection)

Basic essays by Stefan Weinfurter are summarized in the anthology: Lived order - thought order. Selected contributions to King, Church and Empire. On the occasion of the 60th birthday. Edited by Helmuth Kluger, Hubertus Seibert and Werner Bomm. Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2005, ISBN 3-7995-7082-9 .

Monographs

- Salzburg diocese reform and episcopal politics in the 12th century. Archbishop Konrad I of Salzburg (1106–1147) and the Canon Regulars (= Kölner Historische Abhandlungen. Vol. 24). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1975, ISBN 3-412-00275-5 (at the same time: Cologne, university, dissertation, 1973).

- Reign and empire of the Salians. Basics of a time of change. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1991, ISBN 3-7995-4131-4 (3rd edition. Ibid 1992; in English: The Salian century. Main currents in an age of transition. Translated by Barbara M. Bowlus. Foreword by Charles R. Bowlus . University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia PA 1999, ISBN 0-8122-3508-8 ).

- Henry II (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Pustet, Regensburg 1999, ISBN 3-7917-1654-9 (3rd, improved edition, ibid 2002).

- The century of the Salians. (1024-1125). Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2004, ISBN 3-7995-0140-1 (Unchanged reprint, ibid 2008, ISBN 978-3-7995-4105-3 ).

- Canossa. The disenchantment of the world. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-53590-9 .

- The empire in the Middle Ages. Brief German history from 500 to 1500. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56900-5 (2nd, reviewed and updated edition, ibid 2011).

- Charlemagne. The holy barbarian. Piper, Munich 2013, ISBN 3-492-05582-6 .

Editions

- Consuetudines canonicorum regularium Springirsbacenses-Rodenses (= Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Mediaevalis. Vol. 48). Brepols, Turnhout 1978 (text in Latin, foreword and introduction in German).

- The history of the Eichstätter bishops by Anonymus Haserensis (= Eichstätter Studies. NF Vol. 24). Edition - translation - commentary. Pustet, Regensburg 1987, ISBN 3-7917-1134-2 .

Editorships

- with Hanna Vollrath : Cologne - city and diocese in church and empire of the Middle Ages. Festschrift for Odilo Engels on his 65th birthday (= Cologne historical treatises. Vol. 39). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1993, ISBN 3-412-12492-3 .

- with Bernd Schneidmüller : Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? (= Medieval research. Vol. 1). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1997, ISBN 3-7995-4251-5 ( digitized version ).

- with Bernd Schneidmüller: Ottonian new beginnings. Symposium on the exhibition "Otto the Great, Magdeburg and Europe". von Zabern, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-8053-2701-3 .

- with Bernd Schneidmüller: The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I (919–1519). Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50958-4 .

- with Marion Steinicke: Investiture and coronation rituals. Assertions of power in a cultural comparison. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2005, ISBN 978-3-412-09604-5 .

- with Bernd Schneidmüller: Holy - Roman - German. The empire in medieval Europe. Sandstein, Dresden 2006, ISBN 3-937602-56-9 .

- with Bernd Schneidmüller: Configurations of order in the high Middle Ages (= lectures and research. Vol. 64). Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 978-3-7995-6864-7 ( online ).

- with Bernd Schneidmüller: Salian Empire and New Europe. The time of Heinrich IV and Heinrich V Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-20871-5 .

- Papal rule in the Middle Ages. Functioning, strategies, forms of representation (= medieval research. Vol. 38). Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2012, ISBN 978-3-7995-4289-0 ( digitized version ).

- with Jörg Peltzer, Bernd Schneidmüller, Alfried Wieczorek (eds.): The Wittelsbachers and the Electoral Palatinate in the Middle Ages. A success-story? Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-7954-2645-3 .

- with Julia Becker, Tino Licht: Carolingian monasteries. Knowledge transfer and cultural innovation (= material text cultures. Vol. 4). De Gruyter Berlin et al. 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-037123-9 ,

literature

- Inaugural address by Stefan Weinfurter at the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences on January 31, 2004. In: Yearbook of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences for 2004 , Heidelberg 2005, pp. 119–121.

- Michael Bonewitz: I think the finds in the Johanniskirche are a sensation. Interview with Stefan Weinfurter. In: Mainz. Quarterly issues for culture, politics, business. 34, 2014, issue 4, pp. 10-23.

- Jürgen Dendorfer: Stefan Weinfürter (1945–2018). In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. 167, 2019, pp. 425-432.

- Johannes Fried : The historian Stefan Weinfurter is dead. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , September 3, 2018, p. 10.

- Klaus-Frédéric Johannes : On the death of Stefan Weinfurters (June 24, 1945 - August 27, 2018). In: Archive for Middle Rhine Church History 70, 2018, pp. 471–473.

- Oliver Junge: Heinrich. For the sixtieth of the medievalist Stefan Weinfurter. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , June 24, 2005, No. 144, p. 39.

- Gert Melville : Prologue. In: Hubertus Seibert , Werner Bomm, Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2013, ISBN 978-3-7995-0516-1 , pp. 11-15.

- Jörg Peltzer : Stefan Weinfurter (1945–2018). In: Historical magazine . 308, 2019, pp. 711-720.

- Lieselotte E. Saurma : Inaugural lecture Prof. Dr. Stefan Weinfurter. June 21, 2000. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): New ways of research. Inaugural lectures at the Heidelberg Historical Seminar 2000–2006. (= Heidelberg historical contributions. Vol. 3). Winter, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8253-5634-7 , pp. 11-14.

- Viola Skiba: In Memoriam Prof. Dr. Stefan Weinfurter: June 24, 1945 - August 27, 2018. In: Mannheimer Geschichtsblätter 36, 2018, pp. 58–59.

- Bernd Schneidmüller: Binding effect. On the death of the medieval historian Stefan Weinfurter. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , August 30, 2018, No. 201, p. 11 ( online ).

- Bernd Schneidmüller: Stefan Weinfurter (June 24, 1945– August 27, 2018). In: Yearbook of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences for 2018. Heidelberg 2019, pp. 199–202 ( online ).

- Stefan Weinfurter. In: Jörg Schwarz: The Constance Working Group for Medieval History 1951-2001. The members and their work. A bio-bibliographical documentation (= publications of the Constance Working Group for Medieval History on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary 1951–2001. Vol. 2). Edited by Jürgen Petersohn . Thorbecke, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-7995-6906-5 , pp. 425-431 ( digitized version ).

- Herwig Wolfram : Stefan Weinfurter. In: Austrian Academy of Sciences. Almanach 2015, 165th volume, Vienna 2016, p. 192.

- Herwig Wolfram: Stefan Weinfurter. In: Austrian Academy of Sciences. Almanach 2018, Volume 168, Vienna 2019, pp. 396–399.

- Who is who? The German Who's Who. L. Edition 2011/2012, p. 1247.

Web links

- Literature by and about Stefan Weinfurter in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications by Stefan Weinfurter in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- Short biography and reviews of works by Stefan Weinfurter at perlentaucher.de

- Font directory

- Senior Professor Stefan Weinfurter, History Department, Heidelberg University

- Research Center for History and Cultural Heritage (FGKE), University of Heidelberg

- Michael Matheus : An obituary for Stefan Weinfurter , October 5, 2018.

- Claudia Zey : Obituary Stefan Weinfurter , memorial event in Speyer, October 5, 2018.

- Bernd Schneidmüller: Obituary by Stefan Weinfurter , Reichenau, October 9, 2018.

Remarks

- ↑ International Association of Nobles: Lumbe Edle von Mallonitz

- ^ Renate Edle Lumbe von Mallonitz: The last autumn. A historical novel from Bohemia. Heidelberg 2009, pp. 143-145.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Stefan Weinfurter , Reichenau, October 9, 2018; Bernd Schneidmüller: Stefan Weinfurter (June 24, 1945– August 27, 2018). In: Yearbook of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences for 2018. Heidelberg 2019, pp. 199–202, here: p. 199 ( online ).

- ↑ Jürgen Dendorfer: Stefan Weinfürter (1945-2018). In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. 167, 2019, pp. 425–432, here: p. 428.

- ↑ Consuetudines canonicorum regularivm Springirsbacenses-Rodenses. Edited by Stefan Weinfurter. Turnhout 1978.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Sancta Aureatensis Ecclesia. On the history of Eichstatt in the Ottonian-Salian times. In: Journal for Bavarian State History 49, 1986, pp. 3-40 ( online ).

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The history of the Eichstätter bishops by Anonymus Haserensis. Edition – translation – commentary. Regensburg 1987.

- ↑ Joost van Loon , Thomas Wetzstein: Obituary Stefan Weinfurter (1945-2018), website of the Catholic University of Eichstätt ( memento from December 24, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Jörg Peltzer: Stefan Weinfurter (1945-2018). In: Historische Zeitschrift 308, 2019, pp. 711–720, here: p. 718.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Configurations of order in conflict. The example of Henry III. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): Mediaevalia Augiensia. Research on the history of the Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 79-100 ( online ).

- ↑ Jürgen Dendorfer: Stefan Weinfürter (1945-2018). In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. 167, 2019, pp. 425–432, here: p. 430.

- ↑ Hubertus Seibert, Werner Bomm and Verena Türck (eds.): Authority and acceptance. The empire in 13th century Europe. Ostfildern 2013. See the review by Richard Engl in: Journal for Historical Research 43, 2016, pp. 359–361.

- ↑ Supervision of doctoral and post-doctoral theses (initial assessment)

- ↑ Michael Bonewitz: Obituary for the historian Stefan Weinfurter . In: Echo Online , September 6, 2018; Jörg Peltzer: Stefan Weinfurter (1945–2018). In: Historische Zeitschrift 308, 2019, pp. 711–720, here: p. 720.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Stefan Weinfurter (June 24, 1945– August 27, 2018). In: Yearbook of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences for 2018. Heidelberg 2019, pp. 199–202, here: p. 202 ( online ).

- ↑ See Stefan Weinfurter: "Series episcoporum" - problems and possibilities of a prosopography of the early and high medieval episcopate. In: Neithard Bulst, Jean-Philippe Genet (Ed.): Medieval Lives and the Historian. Studies in Medieval Prosopography. Kalamazoo (Michigan) 1986, pp. 97-112.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: 'Series Episcoporum' - Problems and Possibilities of a Prosopography of the Early and High Medieval Episcopate. In: Neidhart Bulst, Jean-Philippe Genêt (Ed.): Medieval Lives and the Historian. Studies in Medieval Prosopography. Kalamazoo 1986, pp. 97-112. Cf. Ursula Vones-Liebenstein: What contribution does prosopography make to theological medieval studies? In: Mikolaj Olszewski (Ed.): What is “theology” in the Middle Ages? Religious Cultures of Europe (11th – 15th centuries) as reflected in their self-understanding. Münster 2007, pp. 695-724, here: pp. 703 f.

- ↑ Helmuth Kluger, Hubertus Seibert and Werner Bomm (eds.): Lived order - thought order. Selected contributions to King, Church and Empire. On the occasion of the 60th birthday. Ostfildern 2005, p. XIII. See the reviews of Ludger Horstkötter in: Analecta Praemonstratensia 82, 2006, pp. 362–363; Alheydis Plassmann in: sehepunkte 6 (2006), No. 9 [15. September 2006], online ; Benoît-Michel Tock in: Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire 85, 2007, pp. 423-427; Wilfried Schöntag in: Rottenburger Jahrbuch für Kirchengeschichte 25, 2006, pp. 352–353; Ulrich Köpf in: Journal for Bavarian Church History 76, 2007, 302–305.

- ↑ See the reviews of August Leidl in: Ostbairische Grenzmarken. Passauer Jahrbuch für Geschichte, Kunst und Volkskunde 18, 1976, p. 616; Siegfried Haider in: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 84, 1976, pp. 440–442; Günter Rauch in: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History. Canonical Department 62, 1976, pp. 422-424; Jürgen Miethke in: Yearbook for the History of Central and Eastern Germany 25, 1976, pp. 338–342; Wilhelm Störmer in: Journal for Bavarian State History 40, 1977, pp. 942–943 ( online ); Peter Johanek in: Mitteilungen des Österreichisches Staatsarchiv 30, 1977, pp. 499–502; Rudolf Schieffer in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 32, 1976, pp. 286–287 ( online )

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Salzburg diocese reform and episcopal politics in the 12th century. Archbishop Konrad I of Salzburg (1106–1147) and the Canon Regulars. Cologne et al. 1975, p. 3.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Salzburg diocese reform and episcopal politics in the 12th century. Archbishop Konrad I of Salzburg (1106–1147) and the Canon Regulars. Cologne et al. 1975, p. 21.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Salzburg diocese reform and episcopal politics in the 12th century. Archbishop Konrad I of Salzburg (1106–1147) and the Canon Regulars. Cologne et al. 1975, p. 294.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Vita canonica and eschatology. A new source for the self-image of the reform canons of the 12th century from the Salzburg reform circle. In: Gert Melville (ed.): Secundum Regulam Vivere. Festschrift for Norbert Backmund. Windberg 1978, pp. 139-167.

- ↑ Cf. on this Stefan Weinfurter: Norbert von Xanten and the origin of the Premonstratensian order. In: Barbarossa and the Premonstratensians (Writings on Staufer History and Art 10), Göppingen 1989, pp. 67–100; Stefan Weinfurter: Norbert von Xanten - founder of the order and "Lord of the Church". In: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 59, 1977, pp. 66–98; Stefan Weinfurter: Norbert von Xanten as reform canon and founder of the Premonstratensian order. In: Kaspar Elm (ed.): Norbert von Xanten. Nobleman, founder of the order, prince of the church. Cologne 1984, pp. 159-188.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The centralization of power in the empire by Emperor Heinrich II. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 106, 1986, pp. 241–297, here: p. 284.

- ↑ Jürgen Dendorfer: Stefan Weinfürter (1945-2018). In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. 167, 2019, pp. 425–432, here: p. 428.

- ↑ See the reviews of Klaus Naß in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 55, 1999, pp. 736–737 ( online ); Matthias Becher in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 63 (1999), pp. 341–345 ( online ); Jonathan Rotondo-McCord in: Speculum 74, 1999, pp. 835-837; Sarah L. Hamilton in: Early Medieval Europe 10, 2001, pp. 150-152; Johannes Fried: The emperors only rule in the texts. At least for the historian: what a turning point depends on how you twist and turn the word. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , March 31, 1998, No. 76, p. 47.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter, Bernd Schneidmüller (Eds.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, p. 8 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ See the reviews of Rudolf Schieffer in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 56, 2000, p. 705. ( online ); Herwig Wolfram in: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 108, 2000, pp. 411–415; Swen Holger Brunsch in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 81, 2001, pp. 687–688 ( online ); Johannes Fried: Glorified high in the kingdom of heaven. The emperor left no son on earth, but he left many problems: Stefan Weinfurter's picture of Heinrich II. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , November 2, 1999, no. 255, p. L20. Knut Görich : New Historical Literature. New books on high medieval royalty. In: Historische Zeitschrift 275/1, 2002, pp. 105–125, here: p. 109 f.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Emperor Heinrich II. And Boleslaw Chrobry. Rulers with similar concepts? In: Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae 9, 2004, pp. 5–25, here: pp. 18f.

- ↑ Cf. Stefan Weinfurter: Sacred monarchy and establishment of rule at the turn of the millennium. The Emperor Otto III. and Heinrich II. in their pictures. In: Helmut Altrichter (Hrsg.): Pictures tell stories. Freiburg i. Br. 1995, pp. 47-103.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, pp. 42-47; Ludger Körntgen: Kingdom and God's grace. On the context and function of sacred ideas in historiography and pictorial evidence of the Ottonian-Early Salian period. Berlin 2001, p. 213.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Otto III. and Henry II in comparison. A résumé. Stefan Weinfurter, Bernd Schneidmüller (Ed.): Otto III. - Heinrich II. A turning point? Sigmaringen 1997, pp. 387-413, here: p. 397 ( digitized version ); Stefan Weinfurter: Sacred monarchy and establishment of rule around the turn of the millennium. The Emperor Otto III. and Heinrich II. in their pictures. In: Helmut Altrichter (Hrsg.): Pictures tell stories. Freiburg i. Br. 1995, pp. 47-103, here: p. 90; Stefan Weinfurter: The claim of Heinrich II to the royal rule 1002. In: Joachim Dahlhaus, Armin Kohnle (Ed.): Papstgeschichte und Landesgeschichte. Festschrift for Hermann Jakobs on his 65th birthday. Cologne et al. 1995, pp. 121-134, here: p. 124.

- ↑ Ludger Körntgen: Kingdom and God's grace. On the context and function of sacred ideas in historiography and pictorial evidence of the Ottonian-Early Salian period. Berlin 2001, p. 225.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Sacred monarchy and establishment of rule around the turn of the millennium. The Emperor Otto III. and Heinrich II. in their pictures. In: Helmut Altrichter (Hrsg.): Pictures tell stories. Freiburg i. Br. 1995, pp. 47-103, here: p. 78.

- ^ Hagen Keller: The portrait of Emperor Heinrich in the Regensburg Gospels from Montecassino (Bibl. Vat., Ottob. Lat. 74). At the same time a contribution to Wipo's "Tetralogus". In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 30, 1996, pp. 173-214.

- ↑ See Stefan Weinfurter: Heinrich II. (1002-1024). Rulers at the end of time. Regensburg 1999, p. 247. f

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Inprimis Herimanni ducis assensu. On the function of DHII. 34 in the conflict between Heinrich II and Hermann von Schwaben. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 34 (2000), pp. 159–185, here: p. 181.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Conflict behavior and individuality of the ruler using the example of Emperor Heinrich II. (1002-1024). In: Stefan Esders (ed.): Legal understanding and conflict management. Judicial and extrajudicial strategies in the Middle Ages. Cologne et al. 2007, pp. 291–311, here: p. 304.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Kunigunde, the empire and Europe. In: Stefanie Dick, Jörg Jarnut, Matthias Wemhoff (Eds.): Kunigunde - consors regni. Lecture series on the thousandth anniversary of the coronation of Kunigunde in Paderborn (1002–2002). Munich 2004, pp. 9–27, here: pp. 16 and 26. Cf. also the review by Laura Brandner in: Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 56, 2006, pp. 213–215.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Charlemagne. The holy barbarian. Munich et al. 2013. See the reviews of Charles West in: Francia-Recensio 2014–3 ( online ); Christoph Galle in: Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch 50, 2015, pp. 341–343; Karl Ubl : Charlemagne and the return of the God state. Narrative of heroization for the year 2014. In: Historische Zeitschrift 301 (2015), pp. 374–390.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Carlo Magno. Il barbaro santo. Translated by Alfredo Pasquetti. Bologna 2015.

- ^ Rudolf Schieffer: Charlemagne after 1200 years. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 70, 2014, pp. 637–653, here: p. 639 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Charlemagne. The holy barbarian. Munich et al. 2013, pp. 15 and 201.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Charlemagne. The holy barbarian. Munich et al. 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Charlemagne. The holy barbarian. Munich et al. 2013, p. 15.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Uniqueness. Charlemagne and the beginnings of European knowledge and science culture. In: Oliver Auge (Ed.): King, Empire and Prince in the Middle Ages. Final conference of the Greifswald “Principes project”. Festschrift for Karl-Heinz Spieß. Stuttgart 2017, pp. 35–52. See the review by Manfred Groten in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 82, 2018, pp. 249–250 ( online ).

- ↑ Jürgen Dendorfer: Stefan Weinfürter (1945-2018). In: Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine. 167, 2019, pp. 425–432, here: p. 428. Articles that appeared during this period: Stefan Weinfurter: Sancta Aureatensis Ecclesia. On the history of Eichstatt in the Ottonian-Salian times. In: Journal for Bavarian State History 49, 1986, pp. 3–40 ( digitized version ); Stefan Weinfurter: The Diocese of Willibald in the service of the king. Eichstätt in the early Middle Ages. In: Journal for Bavarian State History 50, 1987, pp. 3–40; Stefan Weinfurter: From the diocese reform to taking sides with Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian. The foundation of the ecclesiastical sovereignty in Eichstätt around 1300. In: Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte 123, 1987, pp. 137-184 ( digitized version ); Stefan Weinfurter: Friedrich Barbarossa and Eichstätt. On the removal of Bishop Burchard 1153. In: Yearbook for Franconian State Research 52, 1992, pp. 73-84 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ See the review by Alois Schmid in: Historische Zeitschrift 250, 1990, pp. 138-139. Further reviews by Franz-Reiner Erkens in: Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 101, 1990, pp. 109–110; Wilfried Hartmann in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 45, 1989, pp. 648–649 ( digitized version ); A. Izquierdo in: Studia Monastica 31, 1989, pp. 216-217.

- ↑ Harald Dickerhof, Stefan Weinfurter (ed.); St. Willibald - monastery bishop or diocese founder? Regensburg 1990. Cf. the reviews of Matthias Werner in: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, p. 235; Hans Hubert Anton in: Historische Zeitschrift 257, 1993, pp. 465–467; Wilfried Hartmann in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 48, 1992, p. 208 ( online ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Eichstätt in the Middle Ages. Monastery - diocese - principality. Regensburg 2010.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Legitimation of rule and the changing authority of the king: The Salier and their cathedral in Speyer. In: Die Salier und das Reich, Vol. 1: Salier, Adel und Reichsverfassung. Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 55-96; Stefan Weinfurter: Salic understanding of rule in transition. Heinrich V and his privilege for the citizens of Speyer. In: Frühmedalterliche Studien 36, 2002, pp. 317–335; Stefan Weinfurter: Speyer and the kings in Salian times. In: Caspar Ehlers, Helmut Flachenecker (eds.): Spiritual central locations between liturgy, architecture, praise to God and the rulers: Limburg and Speyer. Göttingen 2005, pp. 157-173; Stefan Weinfurter: The Speyer Cathedral. Function, memory and myth. In: Franz Felten (Hrsg.): Places of remembrance in Rhineland-Palatinate. Stuttgart 2015, pp. 9–24.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The fall of the old Lorsch in the late Staufer period. The monastery on Bergstrasse in the field of tension between papacy, archbishopric Mainz and palatinate. In: Archive for Middle Rhine Church History 55, 2003, pp. 31–58.

- ↑ Jörg Peltzer: Stefan Weinfurter (1945-2018). In: Historische Zeitschrift 308, 2019, pp. 711–720, here: p. 717.

- ↑ See the reviews of Veronika Lukas in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 74, 2018, pp. 856–858; Christoph Waldecker in: Nassauische Annalen 128, 2017, pp. 428–430; Hans-Werner Goetz in: Das Mittelalter 22, 2017, pp. 207–209; Rudolf Schieffer in: Historische Zeitschrift 304, 2017, pp. 472–473; Anna Dorofeeva in: Francia-Recensio , 2016-3 ( online ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Conflict and Conflict Resolution in Mainz. On the background to the murder of Archbishop Arnold in 1160. In: Winfried Dotzauer (Hrsg.): Landesgeschichte und Reichsgeschichte. Festschrift for Alois Gerlich on his 70th birthday. Stuttgart 1995, pp. 67-83.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Who was the author of the vita of Archbishop Arnold of Mainz (1153–1160)? In: Karl Rudolf Schnith, Roland Pauler (Hrsg.): Festschrift for Eduard Hlawitschka for his 65th birthday. Kallmünz 1993, pp. 317-339.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Conflict and conflict resolution in Mainz: On the backgrounds of the murder of Archbishop Arnold in 1160. In: Winfried Dotzauer (Hrsg.): Landesgeschichte und Reichsgeschichte. Festschrift for Alois Gerlich on his 70th birthday. Stuttgart 1995, pp. 67-83.

- ^ Stefan Burkhardt: Vita Arnoldi archiepiscopi Moguntinensis. Regensburg 2014, pp. 9–12 ( online ). See the reviews of Christoph Waldecker in: Nassauische Annalen 127, 2016, pp. 379–380; Rudolf Schieffer in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 80, 2016, S, 286–288.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Archbishop of Mainz Arnold von Selenhofen: Vita and Memoria. In: Journal for Württemberg State History 73, 2014, pp. 59–71.

- ↑ See the reviews of Robert Folz in: Mediaevistik 8, 1995, pp. 346–349; Immo Eberl in: Rottenburger Jahrbuch für Kirchengeschichte 11, 1992, pp. 337–338.

- ↑ See the reviews by Julia Barrow: The State of Research: Salian Features: 'Die Salier' at Speyer. In: Journal of Medieval History 20, 1994, pp. 193-206; Kurt-Ulrich Jäschke in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 57, 1993, pp. 306–337; Jean-Yves Mariotte in: Bibliotheque de l'Ecole des Chartes 150, 1992, pp. 375-376; Robert Folz in: Le Moyen Âge 98, 1992, pp. 113–117; Oliver Guyotjeannin in: Francia 19, 1992, pp. 297-298 ( online ).

- ↑ Patrick Geary: A little science from yesterday: The influence of German-language Medieval Studies in America. In: Peter Moraw, Rudulf Schieffer (Ed.): The German-speaking Medieval Studies in the 20th Century. Ostfildern, 2005, pp. 381–392. here: p. 389 ( online ). Stefan Weinfurter: The Salian century. Main currents in an age of transition. Translated by Barbara M. Bowlus. Philadelphia 1999. On Weinfurter's work in English, see the reviews of Eric J. Goldberg in: Early Medieval Europe 10, 2001, pp. 313-314; Jonathan Rotondo-McCord in: Speculum 76, 2001, pp. 811-813; Benjamin Arnold in: Journal of Ecclesiastical History 52, 2001, pp. 122-123.

- ↑ See the reviews of Joachim Ehlers in: Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 43, 1993, pp. 373–374; Bernhard Töpfer in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 42, 1994, pp. 1012-1013; Anja Ostrowitzki in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 57, 1993, pp. 381–383.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Reform idea and royalty in the late Salian empire. Considerations for a reassessment of Emperor Heinrich V. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): Reform idea and reform policy in the Late Sali-Early Staufer Empire. Mainz 1992, pp. 1–45, here: p. 17.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Reform idea and royalty in the late Salian empire. Considerations for a reassessment of Emperor Heinrich V. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): Reform idea and reform policy in the Late Sali-Early Staufer Empire. Mainz 1992, pp. 1–45, here: p. 28.

- ↑ See the reviews of Florian Hartmann in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 88, 2008, pp. 598–600 ( online ); Christine Kleinjung in: H-Soz-Kult , September 17, 2008, ( online ).

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The "new Europe" and the late Salian emperors. Summarizing considerations. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Eds.): Salic Empire and New Europe. The time of Henry IV and Heinrich V Darmstadt 2007, pp. 411–423, here: p. 423.

- ↑ See the reviews of Christian Dury in: Francia 33, 2006, p. 271 ( online ); Rudolf Schieffer in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 64, 2008, pp. 270–272 ( online ); Wilhelm Störmer in: Zeitschrift für Württembergische Landesgeschichte 65, 2006, pp. 453–455.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Configurations of order in conflict. The example of Henry III. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): Mediaevalia Augiensia. Research on the history of the Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 79-100, here: p. 99 ( online ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Configurations of order in conflict. The example of Henry III. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): Mediaevalia Augiensia. Research on the history of the Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 79-100, here: p. 100 ( online ).

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (ed.): Configurations of order in the high Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2006. See the reviews of Christoph HF Meyer in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 63, 2007, pp. 378–380 ( online ); Walter Pauly in: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History, German Department 124, 2007, pp. 452–454; Olivier Bruand in: Francia-Recensio 2009/2 online ; Steffen Patzold in: Journal for historical research 35, 2008, pp. 279–280; Immo Eberl in: Swiss Journal for History 58, 2008, pp. 361–362 ( online ); Jürgen Dendorfer in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 87, 2007, pp. 485–488 ( online ).

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter: Ordnungskonfigurationen. Testing a research design. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Configurations of order in the high Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2006, pp. 7-18 ( online ).

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter: Ordnungskonfigurationen. Testing a research design. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Configurations of order in the high Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2006, pp. 7-18, here: p. 8 ( online ).

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The end of Heinrich IV. And the new legitimation of kingship. In: Gerd Althoff (Ed.): Heinrich IV. Ostfildern 2009, pp. 331–353, here: p. 351 ( online ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Papacy, empire and imperial authority. From Rome 1111 to Venice 1177. In: Ernst-Dieter Hehl , Ingrid Heike Ringel, Hubertus Seibert (eds.): The papacy in the world of the 12th century. Stuttgart 2002, pp. 77-99, here: p. 99 ( online ).

- ↑ See the reviews of Rudolf Schieffer in: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 257-258; Herbert Edward John Cowdrey in: The English Historical Review 111, 1996, pp. 954-955; Detlev Jasper in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 52, 1996, pp. 643–645 ( online ); Pius Engelbert in: Theologische Revue 91 (1995), pp. 231-234; Adelheid Krah in: Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 107, 1996, pp. 258-259; Patrick Henriet in: Le Moyen Âge 103, 1997, pp. 621-625; Götz-Rüdiger Tewes in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 74, 1994, pp. 687-688 ( online ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Archbishop Philipp of Cologne and the fall of Heinrich the Lion. In: Hanna Vollrath, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Cologne. City and diocese in church and empire of the Middle Ages. Festschrift for Odilo Engels on his 65th birthday. Cologne 1993, pp. 455-481.

- ↑ Knut Görich: Hunter of the lion or the driven of the princes? Friedrich Barbarossa and the disempowerment of Henry the Lion. In: Werner Hechberger, Florian Schuller (eds.): Staufer & Welfen. Two rival dynasties in the High Middle Ages. Regensburg 2009, pp. 99–117, here: p. 111.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Empress Adelheid and the Ottonian Empire. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 33, 1999, pp. 1–19, here: p. 19. Cf. the review by Ludger Körntgen in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 58, 2002, p. 331 ( online );

- ↑ See the reviews of Andreas Kilb: The shadow of the body of the king. High-ranking: An anthology about the German rulers of the Middle Ages. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , October 7, 2003, No. 232, p. L34; Rudolf Schieffer in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 69, 2005, pp. 304–305 ( online ); Rudolf Schieffer in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 60, 2004, p. 350 ( online ); Gerhard Köbler in: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History, German Department 126, 2009, p. 503; Jochen Johrendt in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 84, 2004, pp. 595–596 ( online ).

- ↑ See the reviews of Steffen Patzold in: Das Mittelalter 14, 2009, p. 195; Bernd Schütte in: H-Soz-Kult , July 19, 2006, online ; Alois Gerlich in: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History, German Department 124, 2007, pp. 458–460; Rudolf Schieffer in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 63, 2007, p. 274 ( online ); Hans Hubert Anton : Reception, Reform, Synthesis. The new in the old and new from the old. Thoughts on publications on the occasion of the 900th anniversary of the death of Emperor Heinrich IV and the Canossa event in 1076/1077. In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 71, 2007, pp. 254–265 ( online ); Scott G. Bruce in: Speculum 83, 2008, pp. 487-489; Jochen Johrendt in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 86, 2006, pp. 797–798 ( online ); Michael de Nève in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 52, 2004, pp. 854–855.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Canossa. The disenchantment of the world. Munich 2006, p. 207.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Empire in the Middle Ages. Brief German history from 500 to 1500. Munich 2008. See the reviews of Michael Borgolte in: Historische Zeitschrift 290 (2010), pp. 176–177; Ulrich Knefelkamp in: Das Mittelalter 16/1, 2011, p. 213; Christiane de Cracker-Dussart in: Le Moyen Âge 119, 2013, pp. 492–493; Thomas Olechowski in: Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History, German Department 126, 2009, p. 450; Steffen Patzold in: Das Mittelalter 14, 2009, p. 195; Harald Müller in: H-Soz-Kult , October 1, 2008, ( online ); Florian Hartmann in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 89, 2009, pp. 527–528 ( online )

- ↑ See the reviews of Claudia Zey in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 59, 2003, pp. 327–329 ( online ); Benoît-Michel Tock in: Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire 83, 2005, pp. 553–555.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Venice 1177 - turn of the Barbarossa period? For the introduction. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Stauferreich im Wandel. Concepts of order and politics in the time of Friedrich Barbarossa. Stuttgart 2002, pp. 9-25.

- ↑ See the discussions by Jochen Johrendt in: Historische Zeitschrift 297, 2013, pp. 778–779; Robert Paciocco in: Studi medievali 55, 2014, pp. 842-853; Florian Hartmann in: Francia-Recensio 2013/3 ( online ); Kai-Michael Sprenger in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 93, 2013, pp. 420–422 ( online ); Klaus Herbers in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 95, 2013, pp. 477–479.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: How the empire became holy. In: Bernhard Jussen (ed.): The power of the king. Rule in Europe from the early Middle Ages to modern times. Munich 2005, pp. 190-204 and 387-390.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Holy - Roman - German. The empire in medieval Europe. Dresden 2006. See the reviews by Thomas Vogtherr in: Das Mittelalter 13, 2008, pp. 180–181; Rudolf Schieffer in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 62, 2006, pp. 755–757 ( online ).

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Ideas and realities of the empire of the Middle Ages. Thoughts for a résumé. In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Eds.): Holy - Roman - German. The empire in medieval Europe. Dresden 2006. pp. 451-474.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter, Bernd Schneidmüller and Wojciech Falkowski (eds.): Ritualization of political will formation. Poland and Germany in the High and Late Middle Ages. Wiesbaden 2010. See the reviews by Stefan Kwiatkowski in: Journal for historical research 40, 2013, pp. 293–295; Maike Sach in: Yearbooks for the History of Eastern Europe: jgo.e-reviews 2 (2012), 4 ( online )

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter, Marion Steinicke (Ed.): Investiture and coronation rituals. Assertions of power in a cultural comparison. Cologne et al. 2005. See the reviews of Herbert Schneider in: Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 65, 2009, pp. 285–287 ( online ); Franz-Josef Arlinghaus in: Journal for Historical Research 35, 2008, pp. 618–621; Hans-Werner Goetz in: Historische Zeitschrift 282, 2006, pp. 719–720; Jochen Johrendt in: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries 86 (2006), pp. 717–720 ( online ).

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Investiture and grace: considerations on the gratial rule of rule in the Middle Ages. In: Stefan Weinfurter, Marion Steinicke (eds.): Investiture and coronation rituals. Assertions of power in a cultural comparison. Cologne et al. 2005, pp. 105–123, here: pp. 114, 117 and 123.

- ↑ Claus Ambos, Stephan Hotz, Gerald Schwedler, Stefan Weinfurter (eds.): The world of rituals. From antiquity to today. Darmstadt 2005. See the reviews by Klaus Oschema in: Francia 33, 2006, pp. 180–182 ( online ); Gerhard Schmitz in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 61, 2005, pp. 855–857 ( online ); Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge in: Antiquité classique 75, 2006, pp. 431-432.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The ritual of humility as a means of power: King Heinrich II. And his self-humiliation 1007. In: Claus Ambos, Stephan Hotz, Gerald Schwedler, Stefan Weinfurter (ed.): The world of rituals. From antiquity to modern times. Darmstadt 2005, pp. 45-50.