Heinrich I. (Eastern France)

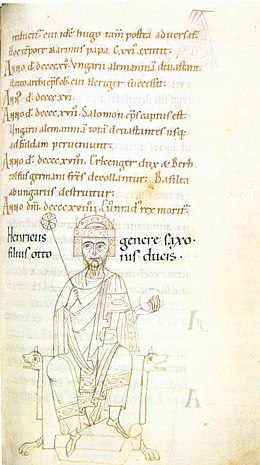

Heinrich I (around 876 ; † July 2, 936 in the Palatinate Memleben ) from the noble family of Liudolfinger was Duke of Saxony from 912 and King of Eastern Franconia from 919 to 936 . The popular nickname of the Vogler is only documented from the 12th century.

When at the beginning of the 10th century repeated Hungarian invasions and the weakness of the late Carolingian monarchy shook the East Franconian Empire, Heinrich succeeded in building a leading position in Saxony through clever marriage connections. He took advantage of the fact that feuds between the powerful aristocratic families for supremacy in the individual tribal areas of the East Franconian Empire led to the establishment of regional middle powers, the later duchies . In contrast to his predecessor Konrad I , Heinrich no longer tried to rule the entire empire as the East Frankish king. Rather, he consolidated his rule over the East Franconian dukes, the duces , through friendship alliances and a far-reaching renunciation of the exercise of power outside of the established but unstable structures. After a nine-year armistice with the Hungarians, which he used to develop extensive defensive measures, he succeeded in 933 against the Hungarians, which had long been considered invincible. In a departure from the Carolingian practice of his predecessors, the empire was no longer divided after his death, but rather passed on to his eldest son from his second marriage, Otto , while the older son Thankmar was not taken into account.

The time of Henry I was one of the poorest sources in the entire European Middle Ages. The Ottonian histories, which were written only decades after his death, pay particular tribute to Heinrich's unification and pacification of the empire, both internally and externally. For a long time Heinrich was considered the first “German” king in the “German Empire”. It was only in modern research that the view prevailed that the German Reich did not come about through an act, but in a long process. Nevertheless, Heinrich continues to play a decisive role in this.

Life up to kingship

Origin and marriage policy

The Heinrichs family can only be traced back to Heinrich's grandfather Liudolf on the paternal side . This is documented several times as comes (count) and as such had the task of exercising royal rights in a certain county, a comitatus . The Liudolfinger estates were located on the western foothills of the Harz , on Leine and Nette with Gandersheim , Brunshausen , Grone and possibly Dahlum and Ahnhausen . The dynasty owed this wealth to a large extent to its close connection to the Carolingian kings of the East Franconian Empire, since Liudolf's ancestors, as Franconian partisans in the Saxon War, were not among Charlemagne's opponents . The most important places of their dominion and centers of the family memoria were the women's communities , which they first founded in Brunshausen and from 881 in the nearby Gandersheim Abbey . Numerous donations and foundations attest to her close relationships with the Gandersheim Abbey.

Liudolf was married to Oda , the daughter of a Frankish great . From this marriage the children Otto , known as the illustrious, and Brun emerged. As a result, Brun probably became the head of the Liudolfinger family. He fell in 880 with an army consisting mainly of Saxony in the fight against Normans . The scanty sources at the end of the 9th century say little about the position of Otto the Illustrious. Otto became a lay abbot of the Imperial Monastery of Hersfeld under circumstances that were not known in detail and thus exercised significant influence on this abbey in the Saxon-Franconian area. Otto is the only attested lay abbot in the East Franconian Empire, which shows the importance of his position. He was married to Hadwig from the Frankish family of the older Babenbergs . Heinrich, among others, emerged from this marriage. A closer family relationship existed between Otto the Illustrious and the Carolingians Ludwig the Younger and Arnulf of Carinthia . Otto's sister Liudgard was married to Ludwig the Younger. Otto probably accompanied Arnulf, who came from an illegitimate connection with King Karlmann , on a train to Italy in 894 . In 897 Otto's daughter Oda and Arnulf's illegitimate son Zwentibold married .

Already during Otto's lifetime a stronger focus on Saxony became clear. At the imperial level Otto appeared only sporadically as an intervener in royal documents between 897 and 906. In the spring of 906 at the latest, he gave Heinrich a military command against the Slavic Daleminzians in the area around Meissen . The outcome of the Babenberg feud , which was conducted over positions of power between the Main Franconian Babenbergers and the Franconian Conradinians , had an impact on the closeness of the greats to the king. The Konradines emerged victorious from the feud and took over the dominant role at the royal court, while the Liudolfinger's closeness to the king was lost. This was the reason for the greater concentration on Saxony. So far the Liudolfinger had tried to enter into marriage connections with members of the Franconian people. A short time later, Heinrich succeeded in marrying Hatheburg , one of the two daughters of the wealthy Saxon nobleman Erwin von Merseburg , and thus expanding the Liudolfingian possessions. Serious canonical objections existed against this marriage, from which a son with Thankmar emerged , since Hatheburg had already become a nun after her first marriage. Hatheburg was sent back to the monastery a little later, but Heinrich kept her rich inheritance in and around Merseburg. In 909, 33-year-old Heinrich married Mathilde , who was probably only 13 , a descendant of the Saxon Duke Widukind , in the royal palace of Wallhausen . The Herford abbess and grandmother Mathilde of the same name gave her consent . Thanks to Mathilde's father Dietrich, a Westphalian count, the Liudolfinger were able to establish connections with the western parts of what was then Saxony.

Duke of Saxony

With the death of Otto the Illustrious on November 30, 912, the new East Franconian King Konrad I had the opportunity to reorganize the situation in Saxony. In Corvey Conrad celebrated the feast of the Purification and confirmed its privileges. On February 18, 913 in Kassel, Konrad assured the imperial monastery of Hersfeld, whose lay abbot Otto had been, the free election of abbots and privileged the monastery of Meschede . As a result, Heinrich was unable to succeed his father as a lay abbot. According to Widukind von Corvey , Konrad refused to give Heinrich all of his father's power. The angry Saxons then advised their duke to enforce his claims by force. According to Widukind's story, which illustrates the hardened fronts between Konrad and Heinrich, Konrad is said to have sought his life with the support of Archbishop of Mainz, Hatto Heinrich. Heinrich was to be persuaded to attend a banquet (convivium) and then killed by means of a specially commissioned golden necklace and rich gifts . However, the murder plot had been betrayed to Heinrich by the goldsmith of the necklace himself. Heinrich then devastated the Thuringian and Saxon possessions of the Archbishop of Mainz. He then distributed these conquests to his vassals . Now Konrad sent his brother Eberhard with an army to Saxony, which however was defeated. In 915 the armies of Konrad and Heinrich met at Grone (west of Göttingen ). Heinrich was militarily inferior to the king and appears to have submitted to an official act of submission by which he recognized King Konrad as king. The East Franconian King and the Saxon Duke agreed on the recognition of the status quo and mutual respect for the zones of influence. After 915 there are no more conflicts between Konrad and Heinrich. Within the research it was even considered that Konrad had already assured his adversary Heinrich of the succession to the throne in Grone.

The opposing ideas of King Conrad and the dukes about the relationship between royalty and nobility could not be reconciled. When Konrad had his brothers-in-law Erchanger and Berthold executed in 917 , Burkhard was made Duke of Swabia by the Swabian nobility. By 916 at the latest, Konrad's relationship with the Bavarian Luitpoldinger Arnulf deteriorated so much that Konrad took military action against him. In the ensuing confrontations, Konrad sustained a serious wound that severely restricted his radius of action and to which he succumbed on December 23, 918.

Royal rule

"Designation" by Konrad I.

Liutprand von Cremona , Adalbert von Magdeburg and Widukind von Corvey describe the transfer of power from Conrad I to Heinrich I in the same way: Before his death, King Konrad himself had given Heinrich the dignity of King and brought him the insignia . His brother Eberhard did this. According to Widukind's much-discussed report, the dying king is said to have ordered his brother Eberhard himself to renounce the throne and to wear the insignia of the highest “state authority” (rerum publicarum summa) for lack of fortuna (happiness) and mores (often in research with “royal salvation”) translated) to the Saxon Duke Heinrich. In the statement that Heinrich became king by the will of Konrad, the reports agree. According to Widukind, however, Eberhard was alone on Konrad's deathbed, while, according to Adalbert Konrad, his brothers and relatives, the heads of the Franks (fratribus et cognatis suis, maioribus scilicet Francorum) , swore to elect Heinrich of Saxony. Liutprand, in turn, had Konrad summoned the dukes of Swabia , Bavaria , Lorraine , Franconia and Saxony to order them to make Heinrich, who was not present, king. Whether there was a designation of Heinrich by the dying Konrad, as Ottonian historiography claims, is disputed in research. The unusually long vacancy of the throne of around five months before the elevation of Heinrich to king in Fritzlar between 14 and 24 May 919 speaks against the execution of a public designation . It therefore seems to have required tough negotiations before the king could be elected.

King's rising in Fritzlar in May 919

In the royal palace of Fritzlar in the Franconian-Saxon border area, Heinrich was raised to king by Franconia and Saxony in May 919. Eberhard had previously settled his relationship with Heinrich. As an amicus regis (friend of the king) and Duke of Franconia, Eberhard remained one of the most important men in the empire until Heinrich's death. After Widukind's much-discussed “waiver of anointing”, the Conradine Eberhard recognized Heinrich as king before the assembled Franks and Saxons. When the Archbishop of Mainz Heriger offered him the anointing with the coronation, Heinrich is said to have replied: "It is enough for me [...] to know ahead of my ancestors that I am called king and have been appointed." Anointing and coronation should Reserved for the more worthy. In contrast to the traditional view, Gerd Althoff and Hagen Keller (1985) related the word maiores in Widukind to “the great” instead of translating it to “ancestors”. According to this understanding, Heinrich's statement is a programmatic utterance that shows his willingness to renounce essential privileges of royalty. In contrast, Ludger Körntgen (2001) would like to understand the term maiores again as an ancestor and refers in this context to Widukind's historiographical conception. According to this, Widukind pursues a “three-tiered structure of Ottonian kingship”: from the modesty of the father towards the ancestors (maiores) , who had already offered Otto the illustrious the crown, to King Heinrich himself, who, in prophetic foresight, does not yet have the anointing would like to reserve the more worthy ones (meliores) who have come , to the consecrated descendants Otto I and Otto II , under whom the kingship came to full development through anointing and coronation.

State of the empire when Henry came to power

Heinrich came to rule under extremely difficult circumstances. Internal and external threats to the empire and at the same time weak Carolingian kingship clearly promoted the efforts of the great at the beginning of the 10th century to consolidate their power in the individual regna (domain) and to claim leadership within the "tribe". In Lorraine, Swabia and Franconia, feuds of the nobility over regional leadership were waged. Heinrich's predecessor Konrad tried in vain to oppose this development. He was unable to enforce his royal rule in Swabia or Bavaria and at the end of his rule remained entirely limited to Franconia. Despite various campaigns, he did not succeed in preventing the loss of Lorraine to Charles the Simple . Heinrich's most urgent task as king was to regulate his relationship with the aristocratic groups in the individual duchies and to reconnect the nobility with the kingship.

In addition to the noble feuds, peace and stability in the empire were shaken by the Hungarian invasions, which led to the loss of legitimacy for rule. The Carolingian army turned out to be too cumbersome against the enemy, who quickly invaded and withdrew again, with their archers. From the end of the 9th century, the Hungarians first threatened the east of the empire. The incursions finally spread from Italy, the Moravian Empire and the East Mark to Bavaria, Swabia, Lorraine and Saxony. The local powers were largely powerless against the Hungarian invasions until the 920s.

Heinrich had to exercise his royal rule by different means than his Carolingian predecessors. The administrative mechanisms from the Carolingian era were no longer available to Heinrich for the administrative penetration of his royal rule. The importance of written form, office and centrality declined. Written form became less important as an instrument of power and communication. The royal court withdrew as the starting point of important tradition. Already under Ludwig the German capitularies disappeared as important documents for the ruling organization from the empire. The institution of the missi dominici (royal messengers), who were supposed to exercise control over the royal officials on site, no longer existed. The dignity of count, which was bestowed by the king according to merit and suitability, had lost its royal official character and developed into an inheritable nobility. Acts of ritual communication gained in importance. The result of this structural change is a “polycentric structure of the rule of law”, which can no longer be interpreted by the king as an instrument. Gerd Althoff exaggerated the lack of elements of modern statehood such as legislation, administration, office organization, judiciary and the monopoly of force as a transition from "Carolingian statehood" to Ottonian "royal rule without a state".

Integration of the dukes into the East Franconian Empire

Swabia

According to Widukind, Heinrich started a campaign against Burkhard von Schwaben immediately after the election . Although Heinrich was unable to assert himself in an invasion of Hungary in 919, Burkhard von Schwaben seems to have submitted to the new king without resistance in the same year "with all his castles and all his people". However, Burkhard had only fought for a ducal position in 917 and was certainly still controversial among the local nobility. In addition, Burkhard was involved in disputes with King Rudolf of Hochburgund . Heinrich contented himself with the duke's vassalage and renounced the direct exercise of rule in Swabia, leaving Burkhard the power of disposal over the treasury and royal rights over the imperial churches. However, under no circumstances was he given complete church sovereignty. At the end of November 920, Burkhard was already present at Heinrich's farm day in Seelheim in Hesse . Heinrich did not enter Schwaben until Burkhard's death. After the death Burkhard in 926 Henry has the Conradines Hermann held the still used a country stranger as Duke of Swabia, infant son to appoint Burkhard Duke. Without his own house power, the new Duke Hermann was much more dependent on Heinrich in his area of responsibility. Heinrich was able to take control of the church.

Bavaria

It was more difficult for Heinrich to achieve recognition of his kingship with Arnulf of Bavaria . Arnulf exercised de facto a kind of royal power in Bavaria since 918. The remark by the so-called Fragmentum de Arnulfo duce Bavariae that Heinrich had attacked a country where none of his ancestors had even one step of land shows how strange it was to accept the Saxon Heinrich as the ruler of East Franconia. The sequence of events that led to an understanding between Arnulf and Heinrich has only been handed down in fragments. It was probably only after a second campaign that Arnulf was ready to recognize Heinrich's kingship. Arnulf opened the gates of Regensburg , went out to Heinrich, submitted to him and was called "the king's friend". Heinrich left Arnulf the right to assign dioceses and the treasury with the important Regensburg Palatinate. In addition, Heinrich never had any property in Bavaria in his documents. As Duke of Bavaria, Arnulf traced his rule back to the grace of God and thereby emphasized his position as a king. In the following years he took part in a court day and appeared four times as an intervener in Heinrich's documents. But he supported Heinrich in his campaigns against Bohemia and Hungary . Heinrich once referred to him in a document as fidelis et dilectus dux noster (“our loyal and beloved Duke”).

Profit of Lorraine

In Lorraine, Heinrich had no intention of contesting the kingship of the West Frankish Carolingian Charles the Simple . But Heinrich got the opportunity to influence the power constellation through party struggles within Lorraine. On November 7, 921, Heinrich had made a friendship alliance with Charles the Simple on a ship in the middle of the Rhine near Bonn (unanimitatis pactum et societatis amicitia) , which included mutual recognition of the respective royal rule and the territorial status quo. 922 changed the situation for Heinrich with the elevation of Duke Roberts of Franzien to the counter-king and gave him an opportunity to draw Lorraine into his domain. At the beginning of 923 an amicitia was agreed with Robert . With this friendship alliance Heinrich violated the first agreement, because Robert was the enemy of his friend Karl. On June 15, 923, Karl attacked his rival Robert in the camp near Soissons . Robert fell, but Karl was defeated in the battle. Karl was captured and in place of Robert, Rudolf of Burgundy was raised to the rank of anti-king in 923. The turmoil in West Franconia, the death of Robert, the elimination of Charles and the rising of Rudolf had a massive impact on the power constellation in Lorraine. After several campaigns by Heinrich, the most important Lorraine great Giselbert recognized his rule in 925 . At the end of 925, all of the Great Lorraine regions submitted to Henry's rule. In retrospect, Lorraine became the fifth duchy of Eastern Franconia. This process was completed by the marriage of Heinrich's daughter Gerberga in 928/29 to Giselbert and his recognition as Duke (dux) .

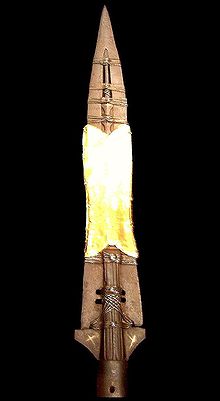

In his policy towards the neighboring western empires, which were also in Carolingian traditions, Heinrich attached great importance to the acquisition of important relics , the transfer of which should serve the spiritual upgrading of the future Quedlinburg Abbey . Heinrich sought the Holy Lance because it was to be regarded as a relic of Christ . Compared to Rudolf II. To Henry even threatened war over the Holy Lance. Historical scholarship concludes that Rudolf II of Burgundy handed over the Holy Lance during his documentary stay at the Worms Court Day in 929. According to the latest research, however, it is uncertain whether the Holy Lance kept in Vienna was ever handed over to King Heinrich and in what form. During the crisis of rule of the West Frankish Carolingians, Charles the Simple sent a cry for help to Heinrich and offered him the hand of St. Dionysius . Heinrich demanded the remains of the saint from the Lorraine abbot of the Servatius Abbey , but only received his stole and staff. The transfer of holy relics to Saxony and the East Frankish Empire had already begun in the Carolingian period; Heinrich increased it considerably.

Nobility politics

Heinrich resolved tensions and conflicts with the nobility by making friends (amici) of his opponents . The relationship between the kingdom and the dukes of Swabia, Franconia and Bavaria was determined by friendship and extensive independence, but only after a demonstrative act of subordination. Unlike his predecessor Konrad, Heinrich did not attempt to appropriate the privileges and means of power of the Carolingian kingship, but left them outside of his own domain to the dukes who had taken over the leadership position in East Franconian regna . The existing balance of power and the renunciation of power outside of Saxony were recognized by Heinrich, but the dukes committed themselves to permanent support and performed military service on military campaigns. The dukes appear first after the king and were the highest in rank when they appeared at the royal court. Dukes' seals and deeds, as well as ducal coins, prove that the dukes were also granted symbols to represent royal power.

Swabia and Bavaria remained regions remote from the king. The dukes had a share in the royal power and, as it were, replaced the royal presence there. In the southern German duchies, the Carolingian royal estate seems to have merged with the ducal foundations, so that the king was deprived of the material basis for keeping court. After paying homage to the dukes, the king probably no longer entered these regions in person and never authenticated there. From 913 to 952 no royal document issued in Swabia or Bavaria has survived. However, an even royal presence in the empire does not seem to have been necessary. Under Heinrich's son Otto, the majority of the documents were issued to Bavarian and Swabian recipients in the central political areas. "The fact that the king did not come to Swabia himself does not say anything about the intensity of his connections with the duke and the greats of the duchy." The peaceful moves into the southern German duchies that began in 952 never applied specifically to the affairs there, but were caused by the Italian policy. Only around the year 1000 under Henry II are all parts of the empire regularly visited by the king.

With the exception of the occupation of duchies, where closeness to the kings and kinship with kings were the decisive prerequisites before the actual right of inheritance, the Liudolfingers have since Heinrich recognized the inheritance of counts and other offices in the aristocratic rule - a process that the Carolingians tried to prevent until the end. This development, however, fundamentally intervened in the clan and family structures and led to conflicts under Heinrich's son Otto, as it curtailed the demands of the more distinguished men closer to the king.

Relationship to the Church

Heinrich placed himself in the continuity of the Frankish kingship and empire. During Holy Week 920 he visited Fulda for the first time , where his predecessor Konrad was buried, and confirmed the privileges conferred by Ludwig and Konrad. Heinrich probably also entered into friendship alliances ( amicitia ) with Frankish imperial bishops . The brotherhood of prayer was established with the bishops . During his reign in Gandersheim Monastery, the Liudolfingian memorial site, the number of bishops accepted there in prayer was increased to almost half of all imperial bishops who died between 919 and 936. Heinrich had himself entered in the Fulda diptych in 923 together with ten imperial bishops and several imperial abbots . The high clergy took over the prayer service against the Hungarian threat as well as for the king and kingdom. Only a few cases are known in which Heinrich ordered the reoccupation of vacant dioceses. More than for other rulers in the Ottonian and Salier times, it may be true of Heinrich that he had to take into account diverging interests within the family, the court orchestra and the episcopate, as well as various groups of the nobility. In Lorraine, Heinrich tried to give his rule further support by staffing dioceses. With the consideration of the Matfridinger Bernoin when filling the office of bishop in the diocese of Verdun , the second strongest aristocratic clan after the Reginars was honored and the lordly ambitions of Giselbert of Lorraine were set back. In 927 Heinrich promoted Benno, a native of Swabia, to the bishopric of Metz . But Metzer Benno not accepted and made him in his second year in office by glare incapacitation. No further investments can be proven in Lorraine.

The episcopal royal service seems to have been weak in Heinrich's time. The king probably stayed in Pfalzen and thus resorted to imperial property for his own supplies. The Archbishop of Mainz , who had been Arch Chancellor since 922, should be considered a close confidante of Heinrich, despite the rejection of the anointing .

Defense against Hungary

Heinrich was powerless against the invading Hungarians in 924 and 926. By a happy coincidence, however, a Hungarian prince was captured, and the Hungarians agreed to a nine-year armistice for his release. Nevertheless, tributes had to be paid to the Hungarians during this period. At the Worms Hoftag in November 926, measures for the defense against Hungary were agreed in order to be prepared for the military conflict after the expiry of the agreement. Widukind's account is supported by a whole series of testimonies in historiography, miracle reports and documents and testifies that similar efforts were carried out across the empire. The activities of Heinrich and the princes were traced back to a decretum in the Hersfeld monastery . According to Carl Erdmann's research contribution, the protection of people from surprise attacks was to be ensured by a so-called “ castle order ”. These 10th century castles were so-called “ring walls” that encircled an area of up to 15 hectares. So-called "Heinrichsburgen", which - caused by the castle order - would have been specially built, cannot be proven according to the current state of research.

Festivals and gatherings should only be held in protected castles. As a second measure, nine of the “rural warriors” (agrarii milites) in Saxony were drawn together to form a solidarity group. One should have his place of residence within the castles so that he could build accommodations for the other eight and store a third of the harvest. The remaining eight were supposed to manage the estates of the ninth. As a further measure to defend against the Hungarians, a cavalry troop was set up.

Preparations for the Hungarian battle also included a pactum (unification) between the king and the populus (people) on the welfare and care of the church. Heinrich promised to forego simony in future . There is now evidence of restitution of church property that had been expropriated to furnish the vassals. Assaults on church property were to be stopped in the future. It is not known what consideration the churches promised for this. But these are to be expected above all in the form of prayers that should implore God's help for the Hungarian war.

Slavic campaigns 928/929

During the time of the peace agreement with the Hungarians, Heinrich led his army in several campaigns against the Slavs. According to Widukind, the intensification of military actions against the Slavs was related to the impending war against Hungary. The relationship between the Slavs and the Saxons was characterized by mutual vengeance and raids. No efforts have been handed down from the Saxons to integrate the pagan tribes of the Slavs into the East Frankish empire and to force them to believe in Christianity. As a first measure, Heinrich attacked the Heveller . The military enterprise was completed with the winter campaign 928/29 and the conquest of the main town Brennaborg / Brandenburg . Then Heinrich attacked the Daleminzier . During the conquest of one of their main locations - Gana Castle - all adults were killed and the children enslaved. Heinrich's extreme hardship against strangers (extranei) is contrasted by Widukind with mildness against internal rebels. Perhaps the Daleminzierland should be weakened in advance as a starting point for the Hungarian trains. Heinrich is also said to have been concerned with protecting his property in Merseburg . Heinrich then moved on to Bohemia with the support of the Bavarian Duke Arnulf . Duke Wenzel , who had retired to Prague, submitted without major resistance and committed himself to regular tribute payments. Wenceslaus was murdered on September 28, 935 by his brother Boleslaw . It was only under Heinrich's son Otto in the summer of 950 that Boleslaw was forced to submit and to serve in the army.

Heinrich's military actions brought Abodriten , Wilzen , Heveller , Daleminzier, Bohemia and Redarians into a tributary dependency. The Slavs responded to the martial attacks of the Saxons with a retaliatory strike by attacking Walsleben Castle and killing all residents of the castle. The war campaign against the Slavs that followed led on September 4, 929 at Lenzen under the leadership of the Saxon Counts Bernhard and Thietmar to a loss-making defeat for the Redarians. All prisoners were killed in the process. In 932 the Lusatians and Milzeners and in 934 the Ukranians made tribute payments.

It is unclear, however, whether Heinrich had developed an overall concept for his policy towards the Elbe Slavs that went beyond mere tribute rule. The Ottonians did not establish a direct, organized rule over the Elbe Slavs. The military trains across the Elbe served to defend the Saxon-Thuringian eastern border and were a Saxon affair. An imperial army was never called up in the 10th century. The relationships are shown in the sources on the one hand by reprisals and reprisals of terrifying cruelty, but on the other hand by negotiations and relationships of a more neighborly character. According to Wolfgang Giese , the subjugated Slavic territories were to be subject to Heinrich's rulership policy in the long term. In the East Franconian Empire there were only a few opportunities for Heinrich to satisfy the aristocracy's striving for honor and property. Beyond the Elbe and Saale, the aristocracy had a wide field of activity: wars had to be waged, booty could be won, lucrative office positions were available, and there were hardly any limits to the acquisition of land.

The control of the Slavic peoples was regulated through the establishment of " brands ", over which individual Saxon greats watched. Meißen Castle was founded to monitor and provide military security for the surrounding area . In front of the walls of the border town of Merseburg, Heinrich and the Merseburg band (legio Mesaburionum) established a military association of warriors who had been banished from their homeland for robbery or manslaughter. They were waived their sentence because of their physical strength and fitness for war. They should be used from Merseburg for reprisals in the Slavic country.

Victory over the Hungarians 933

→ Main article: Battle of Riyadh

At the beginning of the 930s, entries by aristocratic groups in the memorial books of large monasteries such as St. Gallen , Reichenau , Remiremont and Fulda increased . The prayer fraternities promoted a feeling of unity and the maintenance of peace among the noble members of the empire. The intensification of the monastic prayer service, which occurred at the same time, was also a moral preparation for the war. After years of preparation, Heinrich refused the Hungarian ambassadors the tribute, probably in 932. At the beginning of March 933 the Hungarians appeared on the borders of Saxony and Thuringia. Heinrich had set the beginning of the battle on the day of St. Longinus . He obviously wanted to put the victorious power of the Holy Lance, acquired shortly before by the Burgundian King Rudolf II and assigned to Longinus, at the center of the request for heavenly assistance. On March 15, 933, Heinrich's army defeated the Hungarians in the battle of Riyadh , a place that was not clearly identified, probably on the Unstrut . According to the majority of research, all peoples (gentes) of the East Franconian Empire were involved in the battle, for example Bavaria, Swabia, Franconia, Lorraine, Saxony and Thuringia. Heinrich's victory also left a lasting impression in western France. The chronicler Flodoard von Reims reports that 36,000 Hungarians lost their lives in the battle. A statement that, however, is considered unreliable in research.

Widukind emphasizes the divine immediacy of the king, particularly in Heinrich's battle victory. After the victory, the army is said to have praised Heinrich as "father of the fatherland and emperor". Heinrich appears through the victory as the Lord of the kingdom confirmed by God and protector of Christianity. The meaning of the victory is made clear by thanksgiving services and the entry in liturgical manuscripts for March 15, perhaps ordered by the king himself : “King Henry, who defeated the Hungarians”. Heinrich had the victory over the Hungarians immortalized on a mural in the throne room of the Merseburg Palatinate. After Heinrich's death a few years later, however, Merseburg fell to his son Heinrich and was consequently withdrawn from the representation of power together with the painting.

Succession plan ("house rules" from 929)

After the political and military consolidation of his dominion, Heinrich tried to arrange his succession. Heinrich had, in addition to Thankmar from his first marriage to Hatheburg , with his second wife Mathilde the sons Otto , Heinrich and Brun as well as the daughters Gerberga and Hadwig . In a certificate issued in 929 for his wife, the main features of his succession policy can be seen. On September 16, 929 Heinrich guaranteed his wife Mathilde extensive possessions in Quedlinburg , Pöhlde , Nordhausen , Grone and Duderstadt as their Wittum with the consent of the greats and his son at a farm day in Quedlinburg . The document text formulated by the king (D HI, 20) read, "We have considered it appropriate to take care of our house with God's assistance in an orderly manner." ([...] placuit etiam nobis domum nostram deo opitulante ordinaliter disponere. ) In two essays from 1960 and 1964, Karl Schmid derived from the text of the document a “house rule” that was much discussed in research. Schmid interpreted all recognizable measures of the year 929 as related parts of a systematic whole, at the climax of which Otto was officially designated as the successor to the royal rule in 929. In the Medieval Studies Schmid's thesis found broad appeal and encountered only little criticism. According to the latest research results, however, central points of Schmid's argument are based on difficult documents, which can also be regarded as forgeries. A technical discussion of these documents and text-critical statements is still pending.

In view of the abundance of evidence, it becomes clear that the succession to the throne of Otto the Great had begun long before Henry's death. This was by no means a matter of course, because Carolingian practice was to divide the empire among the legitimate sons. With the abandonment of this practice, the individual succession was justified, the indivisibility of the kingship and the empire, which Heinrich's successors should also retain. However, this measure will not be seen as a sign of the strength of the royal rule. Rather, Heinrich was forced to take the duces into consideration: he could no longer divide the empire.

Otto appears in the historical works as rex (king) as early as 929/930 and thus as the sole heir to the title of king. In 929 Heinrich's youngest son Brun was handed over to Bishop Balderich of Utrecht for upbringing for a spiritual career . At this point in time negotiations with the English royal family took place. The English King Aethelstan , who had an ancestor in the holy King Oswald , who had died fighting the heathen and was one of the Christian martyrs, sent his sisters Edgith and Edgiva to Saxony as possible wives of Otto, but wanted to leave the decision to Otto. Heinrich's efforts to tie his house to dynasties outside his empire had been unusual in the East Frankish empire. In addition to the additional legitimation through the connection with another ruling house, this also expressed a strengthening of Saxonism, since the English rulers invoked the Saxons who emigrated to the island in the 5th century.

A list of people in the fraternity book of Reichenau Abbey , which was created after Otto's sister Gerberga (929) married and before Otto's marriage to the Anglo-Saxon king's daughter Edgith (929/930), Otto lists just like his father as rex (king). None of the other relatives, no other son carried this title. The development of the entry in the 1960s by Karl Schmid proves that in 929/930 official determinations regarding the question of succession were made. Apparently only one of the sons, the eldest, should hold the royal dignity in the future.

The special significance of the events is also evident in the king's itinerary . It extends further than before and affects all parts of Francia et Saxonia ("Franconia and Saxony"). After Otto's wedding with Edgith in 930, Heinrich presented the designated heir to the throne in Franconia and in Aachen to the greats of the respective regions in order to obtain their approval for the regulation of the succession to the throne. However, there is no evidence of any ruling activity in the years 930 up to Otto's assumption of power in 936.

Last years and Quedlinburg as a memorial site

In the year 934 Heinrich was able to persuade the Danish king Knut , who ruled until Haithabu in today's Schleswig, to submit, to pay tribute and to accept the Christian faith. Towards the end of his life Heinrich is said to have planned a train to Rome - to Widukind - which, however, was thwarted by an illness. In Ivois am Chiers on the border of the West Franconian and East Franconian empires, a meeting of the Epiphany took place in 935. Heinrich affirmed and renewed friendship alliances with the Burgundian King Rudolf II and the West Franconian King Rudolf . Towards the end of 935, Heinrich probably suffered a stroke while hunting in the Harz Mountains. But he recovered enough that he could convene a court day. In the early summer of 936 the state of the empire was discussed in Erfurt (de statu regni) . Heinrich once again strongly recommended Otto as his successor. After Otto's designation, Heinrich resigned his other sons with property and valuables (praedia cum thesauris) . Heinrich went from Erfurt to Memleben. There he suffered another stroke and died on July 2, 936. Heinrich's body was buried in Quedlinburg . Mathilde survived Heinrich by more than thirty years and found her resting place at his side. According to new building-historical findings, Heinrich and his wife Mathilde were at the original burial site until at least 1018. His whereabouts are unknown.

With Quedlinburg, Heinrich had created his own memorial site , although the memoria of the Liudolfing family had previously been kept in Gandersheim. Babette Ludowici concludes from aristocratic graves of the 5th century that Quedlinburg "in the time around 900 was an important place for the elite of East Saxony for generations". Heinrich therefore used this place for his staging as king and for his relationship with the (East) Saxon noble families. Above all, the favorable location at the crossroads of important traffic routes and the good natural conditions explain why Heinrich chose Quedlinburg. Heinrich's relationship with this place can be traced back to Easter in 922. It is also the oldest known written mention of the place. Of four localizable Easter celebrations, three can be associated with Quedlinburg. In doing so, he tried to establish a tradition that his Ottonian successors continued until Henry II.

The written documents of the 10th and 11th centuries paint a picture of the extremely conscientious maintenance of the memorial by the queen widow Mathilde in Quedlinburg. The commemoration of the royal couple continued in the Quedlinburg monastery area even after the Reformation was introduced in 1540. In the early modern period, the liturgical memoria turned into a memory of Heinrich as the founder of the monastery, who was even regarded as emperor. The Quedlinburger Schautaler showed Heinrich as emperor on the occasion of the centenary of the Reformation in 1617. As an imperial foundation, the Quedlinburger Stift wanted to emphasize prestige and independence in politically troubled times.

Impact history

Change in the understanding of rule under Otto I.

Heinrich's reign, which was largely characterized by internal pacification and unification, ended in 936 when his son Otto I came to power. For Heinrich's successor, the importance of formal friendships declined. In the first few years Otto disregarded the conditions of the compensation created by his father and rejected claims of individual rulers in the allocation of offices. Not least, his decisions were directed against “friends” of the father, who “never refused anything” to them. Heinrich's hereditary regulation contributed significantly to the conflicts that broke out. The practice of bequeathing the whole kingdom to the eldest son made the later son Heinrich become a rebel. The various small uprisings that triggered the first crisis of power could not be settled until 941.

Gerd Althoff and Hagen Keller attributed the break in friendship alliances, which are based on the emphasis on equality, to the king's changed understanding of rule. Otto's measures were aimed at the enforcement of ruling power of decision, and he deliberately disregarded aristocratic claims. This led to the crises and conflicts in Otto's early years. Matthias Becher , on the other hand, emphasizes that the disputes with Eberhard , the "kingmaker" of 919, primarily concerned his position as secundus a rege , a second after the king, which Otto was probably his brother to clarify the situation within the royal family Heinrich had intended.

Heinrich in the judgment of Ottonian historiography

Written form lost a lot of its importance at the beginning of the 10th century. From the years 906 to 940 no contemporary sources of the East Franconian Empire have survived, apart from brief annals. It was not until the middle of the 10th century that a whole series of historical works emerged ( Widukind , Liudprand , Hrotsvit or Thietmar von Merseburg ), which deal with the prehistory and the history of their own time, even the Ottonian ruling house itself. The Ottonian histories were written at a time when the Liudolfinger's position as kings in the East Franconian-German Empire was established and Otto the Great was even able to reach for the imperial crown. Your messages about the time of Henry I are not primary information, but memories and reflect the state of knowledge and the perspective from the time of Otto I and Otto II .

The most important source for the history of Heinrich I's events is the Saxon history of Widukind von Corvey. Widukind, who entered the Corvey monastery around 941/942 , wrote a story of the Saxons around 967/968, which he dedicated to Heinrich's granddaughter Mathilde , who was around thirteen . Widukind's work describes the history of the Saxons from the conquest of a small seafaring community from the 6th century to the fortunate assertion against Thuringians and Franks to the attainment of supremacy, which they appear as lords of Europe under their King Otto at the time Widukind wrote leaves. Heinrich is “only” the last step towards the Saxon perfection that is achieved with his son Otto.

The Ottonian historiography emphasizes the pacification, unification , integration and stabilization of the empire in appreciating the overall achievement of Henry I. Heinrich succeeded in pacifying the empire, which was torn by acts of violence, conflict and fighting. Even the brief annalistic reports on Henry's reign repeatedly emphasize the establishment of peace as the king's main goal. Widukind von Corvey describes Heinrich I's early years under the motto of peacemaking and unification. With the means of consensual peacemaking and victorious warfare against external enemies, which were unusual for his time, Heinrich became the regum maximus Europae for Widukind (greatest among the kings of Europe). The later Archbishop Adalbert von Magdeburg , who continued the world chronicle of Reginos von Prüm , introduced the king into history as "an ardent promoter of peace" (precipuus pacis sectator) who began his government with "strict management of peace".

Since the 80s of the 10th century, Heinrich was a "sword without a pommel" (ensis sine capulo) because of his rejection of anointing . The fact that the annalist Flodoard von Reims refused the rex title in his account should also have its origin in this. In the late Tonic period, Heinrich was exposed to increased criticism from the Merseburg bishop Thietmar . Not only is Heinrich the renunciation of anointing counted as a sin, but because of the canonically problematic marriage to Hatheburg and the fathering of the younger Heinrich on Maundy Thursday , he is accused of a serious violation of moral norms. In the reprehensible disregard of required abstinence on the night before Good Friday , Thietmar saw a parallel to the fate of a Magdeburg resident who had been severely punished for something similar. Heinrich's misconduct charged the family of the Heinriche with the curse of "quarreling", and a "quarreling" was not suitable for the dignity of the king who had to make peace. It was not until 1002, when Henry II came to power , that “the evil weeds withered and the bright blossoms of healing peace broke”. Nevertheless, Heinrich's rule is judged positively, as for Thietmar he is the actual founder of Merseburg and founder of the Ottonian dynasty.

Literary and legendary reception

The gaps in the written tradition were filled in the high and late Middle Ages with rich legends, so that Heinrich was given nicknames such as Vogeler, Finkler, castle builder, town founder. In legendary legends, the Pöhlder annals wrote in the 12th century that Heinrich, nicknamed “the bird ” (auceps), was hunting birds when Franconian messengers suddenly arrived to pay homage to him as king. Since Georg Rüxner's beginning, origin and origin of the tournament in the Teutscher Nation (1532), Heinrich was also considered to be the founder of German tournaments. The Bohemian Chronicle of Hajek von Libotschan (1541) reports that Heinrich's daughter Helena was kidnapped to Bohemia by an unsuitable lover and that she lived there in loneliness for years. When Heinrich got lost on the hunt, he stopped by the castle and found his daughter again. Then he comes back with army power. Only Helena's threat of wanting to die with her lover brings about reconciliation with her father. This episode was picked up several times in the 18th and 19th centuries: in the 1710 Singspiel Heinrich der Vogler by Johann Ulrich König , as a knight drama Emperor Heinrich der Vogler from 1815 by Benedikt Lögler and in 1817 Heinrich the Finkler as a play in one act based on old German Template by August Klingemann .

In the 19th century Heinrich was better known under the name "der Finkler" or "der Vogler". The opinion of the educated middle class about Heinrich was deeply influenced by the poem "Herr Heinrich is sitting at the Vogelherd ..." by Johann Nepomuk Vogl (1835), known early on through the setting of the ballad composer Carl Loewe (1836). It is considered to be the most haunting processing of the Heinrich fabric. Georg Waitz's scientific presentation led to numerous historical dramas. The historical novels by Friedrich Palmié ( Hatheburg 1883) and Ernst von Wildenbruch ( The German King 1908) focused on Heinrich's relationship with Hatheburg. The Silesian poet Moritz Graf von Strachwitz ascribed Heinrich in his poem ( Heinrich der Finkler 1848) the attributes of savior of the fatherland, city founder and conqueror of the heathen.

In the pictorial cycles and pictorial works of the 19th century, Heinrich's striving for national unification was hardly dealt with, unlike in historical studies. With the Hohenzollerns , even after the founding of the empire , Heinrich stepped back significantly behind other medieval rulers such as Charlemagne or Friedrich Barbarossa . The processing in history painting or monuments remained regionally shaped. Heinrich played a central role in the Kingdom of Saxony . Eduard Bendemann created four big ones for the New Throne Room in Dresden Castle with "Heinrich converts the Danes", "The Battle of Riyadh", "Heinrich I as the founder of the city" and "The payment of the tithe and the admission of the peasants into the cities" Wall frescoes with scenes from the life of Henry I. The Wettins wanted to represent the modern kingdom in the 19th century by directly referring to the first Saxon king as an unbroken order. Bendemann published his compositions as reproduction graphics. As a result, the image equipment spread far beyond the Kingdom of Saxony. For the front of the plenary hall in the Merseburger Ständehaus , Hugo Vogel created mural depictions of the Ottonian era with Heinrich's reception of the royal crown at Finkenherd in Quedlinburg and Heinrich's victory over the Hungarians at Riade. On the occasion of its city millennium, Merseburg unveiled the King Heinrich Memorial in 1933 .

Images of history and research controversies

Sybel-Ficker dispute

Medieval Ostpolitik became a topic of academic debate in the 19th century when historians tried to decide the national structure of Germany, the so-called Großdeutsche or Kleindeutsche solution , using historical arguments. The medieval rulers of a multi-property empire were criticized by historical scholars , especially in the 19th century, for failing to recognize the need for a strong nation state. The Protestant historian Heinrich von Sybel described medieval imperial politics as the “grave of national welfare”. In the opinion of historians with a Prussian-Kleindeutsch inclination in the 19th century, “Ostpolitik” instead of “Kaiserpolitik” would have been the national task of the German kings. In the east lasting profits could have been achieved in large areas. Heinrich I went this way, but his son Otto had steered the forces of the empire towards a wrong goal. Henry I consequently drew the recognition of Sybel. For him Heinrich was "the founder of the German Empire and [...] creator of the German people" as a "star of the purest light in the wide firmament of our past". The Austrian historian Julius von Ficker , advocate of a Greater German solution including Austria, defended the medieval imperial policy against Sybel's views and above all emphasized the national and universal importance of the German Empire from a pan-European perspective. The contradiction of viewpoints developed as a Sybel-Ficker dispute into a larger, written controversy. Ficker was ultimately more persuasive, but Sybel also repeatedly found followers in the later Heinrich literature with Georg von Below and Fritz Kern .

Conviction of the emergence of the German Empire under Heinrich I.

The reign of Henry I is a classic topic in medieval research, as it was significant for the continued existence of the East Franconian Empire after it broke away from the Carolingian dynasty. The empire of Henry I and his son Otto I was generally known as the "German Empire" from the 19th century to the 20th century.

In Wilhelm von Giesebrecht's five-volume “History of the German Imperial Era” from 1855 , the election of Heinrich as king signified the “beginning of a new German empire”, “with Heinrich begins the history of the German empire and the German people, as one from that time to the present day has grasped the concept of the same ”. According to Giesebrecht, Heinrich achieved the necessary breakthrough by "with an inventive and fearless spirit" leaving the "tribes" to the order they were responsible for by the respective duke and thus designing a kind of federal structure for his empire under his "chairmanship".

The first monograph on Heinrich I by Georg Waitz , based on the historical-critical method, followed Giesebrecht's assessment of the importance of Heinrich's monarchy for German history. According to Waitz, Heinrich was "a German King in the full sense, his rule a true German Empire".

This conviction that Heinrich founded the German Empire was also supported by Karl Lamprecht at the turn of the 20th century . According to him, the correctness of the Saxon Heinrich was the quality that made him “the founder of the empire”. The scientific authorities Lamprecht, Giesebrecht and Waitz did not have to fight for their views on the beginning of the German Empire to be recognized. You shared this opinion with the majority of your contemporaries. The assessment of the person and government of Heinrich as the “first German king” was retained in this form until the end of the 1930s and was never discussed in a pronounced form.

Only Karl Hampe and Johannes Haller linked the beginning of the German Empire with the election of Konrad I in 911. Since Georg Waitz, no major account of Heinrich has been written. Rather, individual questions were in the foreground for decades. Martin Lintzel and Carl Erdmann in particular made substantial contributions to Heinrich research. The question of Heinrich's motive, which led to the rejection of the anointing offer, concerns Heinrich research most intensively to this day. Historians with a culture-fighting attitude saw in Heinrich's behavior a necessary liberation against clerical interference in the interests of the state. The assumption that Heinrich's character and politics were hostile to the church is now considered to be long out of date.

The nation-state perspective from which Heinrich's rule was viewed also led to criticism and devaluation. For Karl Wilhelm Nitzsch , Heinrich had not achieved the goal of his historical destiny because he had died "without having approached the tasks that were set for his house with a clear, resolute policy [...]". Nitzsch meant a tighter central government subordinating the ducal intermediate powers, as was enforced by Otto I. But even Nitzsch did not deny that Heinrich was owed "the beneficial establishment of German power". In 1930 Walther Schulze also criticized his account in “ Gebhardt's Handbook of German History ”, because Heinrich had not defended the idea of the Reich energetically enough either internally or externally. In the fight against the Slavs and Hungarians, Heinrich was "determined not by national, but by particularist points of view".

The picture of Heinrich under National Socialism

For the ideologues of National Socialism , "the national gathering of Germans" began under Heinrich I, and "the conscious attempt at national establishment and cultivation" under Otto the Great. This tenor was soon spread by all training centers of the party up to the “ Völkischer Beobachter ”. On the other hand, Heinrich Himmler and some historians such as Franz Lüdtke in particular wanted to see Otto's father Heinrich I as the founder of the German people, whose work the son then betrayed. To mark the thousandth anniversary of death in 1936, Himmler stylized Heinrich I in his speech in Quedlinburg as a late Germanic leader. Heinrich was chosen as the “noble farmer of his people”, the “leader a thousand years ago”, the “first among equals”. According to a contemporary claim, Himmler is said to have even considered himself a reincarnation of Henry I. This is usually viewed more cautiously in the scientific literature. The reason for the extraordinary emphasis on this medieval ruler can be found in the parallelism of the overall political constellation. This parallelism was seen in Henry's opposition to clerical universalism and the assertion against France and Slavism. As a result of the establishment of numerous fortifications on what was then the German “Hungarian border”, which was operated by Heinrich I, Heinrich appeared in Himmler's view as the earliest protagonist of a German orientation towards the East.

The commemorative year 1936 also led to the publication of larger representations about Heinrich. For the leader of the national eastern movement, Franz Lüdtke , Heinrich prepared the "great eastern state" with his militant, colonialist grip on the East. The armistice signed with the Hungarians in 926 is compared to the “imposed dictated peace” of 1918, which absolutely had to be broken. The victory against the Hungarians finally succeeded with the "strong unity of leader and people". Alfred Thoss classified his depiction of Heinrich in the blood and soil ideology .

The standard work far beyond the post-war period, it was the first time in 1941 published work history of Saxon empire of Robert Holtzmann . According to Holtzmann, the empire was founded in 911. Heinrich left the empire “solid and secure”. However, the dukes were not yet assigned or subordinated to imperial power and their spiritual life had not yet developed. For Holtzmann, the cooperation of all the tribes in Heinrich's victory over the Hungarians was his greatest achievement. His cautious description of the events and a demythed view, especially of Ostpolitik, characterize the basic attitude of Heinrich research after the Nazi era.

Modern research

Question about the origin of the medieval empire

The conviction that the beginning of the German Empire under Heinrich I should be in the year 919 or in another epoch year was first questioned by Gerd Tellenbach (1939). But the idea of the creation of the German Empire in a long-lasting process in the early Middle Ages , in which the time of Henry I was still significant, was no longer disputed in the period that followed. At the beginning of the 1970s, Carlrichard Brühl, in deliberate contradiction to the view that had prevailed up to that point, took the position that “Germany and France only become comprehensible as mature, independent entities” around 1000 to 1025. After Brühl, Heinrich II was the first ruler who could be called a German king. The Ottonian and the late Carolingian - early Capetian times were not yet a chapter in German or French history for Brühl, but were regarded as an era of inner Franconian actions.

Since the 1970s, through the studies of Joachim Ehlers , Bernd Schneidmüller and Carlrichard Brühl, the view has prevailed that the "German Empire" did not come into being as the result of an event associated with a year like 919, for example, but rather as the result of a process that began in the 9th century and was in part not yet completed even in the 11th and 12th centuries. The Ottonians Heinrich I and Otto I are no longer regarded as figures who symbolize Germany's early power and greatness, but rather as distant representatives of an archaic society.

Judgment on the rule of Heinrich

In the first handbook of German history after 1945, Helmut Beumann described the years 919 to 926 as "turning away from the Carolingian tradition". As a sign of this renunciation, Beumann saw the rejection of the offered anointing and the renunciation of the court chapel and chancellery. In his last three years Heinrich finally had a position “as an occidental hegemon”. At the end of the 1980s, Beumann said goodbye to the idea that the Liudolfinger's renunciation of anointing was a programmatic act, and instead emphasized the pragmatic effort to reach agreement with the most important forces in the Reich.

In the last three decades, the Ottonian period, which began with Heinrich I, was fundamentally reassessed, particularly by the historians Johannes Fried , Gerd Althoff , Hagen Keller and Carlrichard Brühl . The double biographies of Heinrich I and Otto the Great , published in 1985, are the first evidence of the re-evaluation in Heinrich research . A new beginning on the Carolingian legacy of Althoff and Keller. Before that, in 1981/1982 Althoff and Karl Schmid, as part of the research project “Group formation and group consciousness in the Middle Ages” , looked more closely at the name entries in the Reichenau monastery book and compared them with those of the St. Gallen , Fulda and Remiremont women's monastery in Lorraine . The monastic commemorative books served the medieval need to maintain the memoria . It is noticeable that in the Reichenau Memorial Book, which was laid out in 825, these entries have swelled significantly since 929 and suddenly fell off again with Heinrich's death in 936. Such grouped name entries were found in a similar form in the memorial books of St. Gallen and Remiremont and in the death annals of the Fulda monastery. They provide information that these groups have registered their members in the prayer aid of several monasteries. Heinrich had entrusted himself and his family to the commemoration of prayer together with worldly and spiritual greats in different places . Such associations were aimed at peaceful family cohesion and mutual support among group members. Heinrich had taken up these relationships with aristocratic associations of persons, concluded amicitia or friendship alliances and oaths and formed them into an instrument of connection with the greats of the empire. Since then, they have been considered a characteristic of the ruler personality of Heinrich I. Keller and Althoff have shown that the consolidation of Heinrich's kingship was essentially based on balancing the great with the political means of amicitia and pacta . With the research of the Amicitia policy, a progress in knowledge in Heinrich research that has not been recorded for a long time has been achieved. On the basis of the results of the Amicitia alliances, Althoff and Keller put up for discussion whether Heinrich's settlement with the dukes of Swabia and Bavaria, which had been made on the basis of friendship alliances, was not based on the insight that their claim to royal power within their duchies "hardly justified or "was justified", "as his own claim to the rule of kings in the East Franconian Empire". The thesis of the Amicitia alliances was received consistently positively by subsequent research and quickly adopted.

In his account, Johannes Fried (1994), distrusting Ottonian historiography, attached greater weight to the documents and tried to extract statements from them that exceeded their factual content. For him Heinrich is “a genius of procrastination. There was always negotiation, he recognized the position of the dukes and the confrontation ended in friendship. "

In the assessment of the person and rule of Henry I, the current research opinions show no serious differences. For the last years of his life, Heinrich is assigned a hegemonic position in the Christian West, and his position is often characterized by reference to the figure of a primus inter pares , an image that emerged before the mid-19th century.

In May 2019 it was the 1100th anniversary of Henry I's rising as king. On this occasion, the interdisciplinary conference 919 - Suddenly King took place in Quedlinburg from March 22 to 24, 2018 . Heinrich I. and Quedlinburg . The presentations at the conference were published in 2019. From May 19, 2019 to February 2, 2020, the special exhibition 919 - and suddenly King on the life and work of Henry I was on view in the castle museum and the collegiate church Quedlinburg .

Controversy about Widukind as a source for Henry I's accession to the throne

With the extensive news handed down by Widukind von Corvey and Liutprand von Cremona , which are clearly written from a Saxon-Ottonian and Italian-Ottonian perspective and report on the time of Henry I from a retro perspective, the question of the effectiveness of a culture of memory is with regard to the reproduction of facts raised. In 1993, Johannes Fried's criticism of the tradition of the elevation of Henry I as king caused a sensation . Fried used Ottonian historiography to show how historiography is to be assessed, which originated in a time when oral transmission was the predominant one was. The knowledge about the past was subject to constant changes, because the historical memory "changed incessantly and imperceptibly, even during the lifetime of those involved". Fried postulated a process of constant change, which after a certain period of time regularly leads to the result that the underlying event is distorted beyond recognition. The resulting view of the past was “never identical with actual history”. According to Fried, Widukind's story of Saxony is a “fault-saturated construct”. Fried's conclusion for Heinrich's elevation to the King is: “There was probably never a general election of Henry by Franconia and Saxony. [...] He began as a king in Saxony and gradually pushed his kingship into an area that was free of kings after Conrad I. "

Gerd Althoff , who Widukind concedes a particularly high source value, took a particularly strong position against Fried's research position . According to Althoff, the freedom of change and thus also of deformation were set narrow limits as soon as it came to matters in which the powerful had a current interest. Any modifications were therefore not possible. Of course, the expectations of the powerful also favored whitewashing and idealizations. In addition, the numerous anecdotes, dreams and visions that are often mentioned in Ottonian historiography have an argumentative core with which to criticize the powerful.

Furthermore, according to Althoff, it is probable that Widukind's work, which he dedicated to the abbess Mathilde , had a specific causa dedicandi : After the death of Archbishop Wilhelm von Mainz in 968, the twelve or thirteen year old girl Mathilde was the only member of the imperial house north of the The Alps remained, and they remained so until 972. In this situation, Widukind's work was suitable "to make the young Emperor's daughter Mathilde politically capable". The text gave her the knowledge she needed to “represent the Ottonian rule in Saxony”. If one assumed that the history of Saxony had the character of a prince mirror , then for Althoff the weighting of the work and the omissions would also explain themselves (summary of the Italian policy in one chapter, no mention of the mission policy in the east and also not a word about the processes of the foundation of the Archdiocese of Magdeburg). Althoff's conclusion is therefore: “The key witness is trustworthy.” Althoff was also able to confirm the fundamental statements of Ottonian historiography from new research findings, such as those on memorial tradition and conflict research. Hagen Keller pointed out that there were still contemporary witnesses in 967/968 who had witnessed the events from the time of Heinrich I. Keller expresses fundamental concerns about being able to transfer the research results obtained by ethnology on techniques of oral tradition in almost scriptless cultures to an author like Widukind, who was literarily educated. The current Heinrich research moves between the two extreme positions of Althoff and Fried.

swell

Certificates and registers

- MGH : Diplomata regum et imperatorum Germaniae, vol. 1. The documents of Konrad I, Heinrich I, and Otto I , published by Theodor Sickel , Hanover 1879–1884.

- Johann Friedrich Böhmer , Emil von Ottenthal , Hans Heinrich Kaminsky : Regesta Imperii II, 1. The regests of the Empire under Heinrich I and Otto I , Hildesheim 1967.

Literary sources

- Widukind von Corvey : The Saxon history of Widukind von Corvey. In: Sources on the history of the Saxon imperial era. (= Freiherr vom Stein Memorial Edition. Vol. 8.). Edited by Albert Bauer, Reinhold Rau. 5th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2002, pp. 1–183

- Liutprand of Cremona : Works . In: Sources on the history of the Saxon imperial era. (= Freiherr vom Stein Memorial Edition. Vol. 8.). Edited by Albert Bauer, Reinhold Rau. 5th edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2002, pp. 233-589.

- Thietmar von Merseburg, chronicle . Retransmitted and explained by Werner Trillmich . With an addendum by Steffen Patzold . (= Freiherr vom Stein memorial edition. Vol. 9). 9th, bibliographically updated edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-24669-4 .

literature

General representations

- Gerd Althoff : The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 3rd, revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-17-022443-8 .

- Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller : The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and consolidations 888-1024 (= Gebhardt. Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 3). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-608-60003-2 .

- Helmut Beumann : The Ottonians. 5th edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 2000, ISBN 3-17-016473-2 .

- Matthias Becher : Rex, Dux and Gens. Investigations into the development of the Saxon duchy in the 9th and 10th centuries (= historical studies. Vol. 444). Matthiesen, Husum 1996, ISBN 3-7868-1444-9 .

- Gabriele Köster, Stephan Freund (Ed.): 919 - Suddenly King. Heinrich I. and Quedlinburg (= series of publications by the Center for Medieval Exhibitions Magdeburg. Vol. 5). Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-7954-3397-0 .

- Johannes Fried : The way into history. The origins of Germany up to 1024. Propylaea, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-548-26517-0 .

- Hagen Keller: The Ottonians. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-44746-5 .

- Ludger Körntgen : Ottonen and Salier. 3rd reviewed and bibliographically updated edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-23776-0 .

- Timothy Reuter (Ed.): The New Cambridge Medieval History 3. c. 900-1024. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, ISBN 0-521-36447-7 .

Biographies

- Gerd Althoff and Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great: A new beginning on the Carolingian legacy. 2 parts. Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen 1985, ISBN 3-7881-0122-9 .

- Wolfgang Giese : Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-18204-6 . ( Review )

- Bernd Schneidmüller : Heinrich I. (919-936) . In: Bernd Schneidmüller, Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I (919–1519). Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50958-4 , pp. 15-34, 563 f. ( online )

- Georg Waitz : Yearbooks of the German Empire under King Heinrich I. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1863, also reprinted in 1963 of the edition from 1885. ( available at google books )

Web links

- Certificate from Heinrich I for Hersfeld Monastery, dated June 1, 932 with reproduction of the seal, digital version of the image in the photo archive of older original documents from the Philipps University of Marburg

- Publications on Heinrich I in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- Maren Gottschalk : May 12, 919 - Heinrich I becomes King of East Franconia . WDR ZeitZeichen (Podcast with Bernd Schneidmüller )

Remarks

- ^ Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Matthias Becher: The Liudolfinger. Rise of a family. In: Matthias Puhle (Ed.): Otto the Great, Magdeburg and Europe. Vol. 1, Essays, Mainz 2001, pp. 110–118, here: p. 112.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. 2nd expanded edition, Stuttgart et al. 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ Matthias Becher: Otto the Great. Emperor and Empire. A biography. Munich 2012, p. 69. See Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 17.

- ↑ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 21.

- ^ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 22.

- ↑ Matthias Becher: From the Carolingians to the Ottonians. The royal elevations of 911 and 919 as milestones of the change of dynasty in Eastern Franconia. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I .: On the way to the "German Reich"? Bochum 2006, pp. 245-264, here: p. 260; Matthias Becher: Otto the Great. Emperor and Empire. A biography. Munich 2012, p. 74; Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1–2, Göttingen et al. 1985, p. 59.

- ↑ Roman Deutinger: King's election and Duke's raising of Arnulf of Bavaria. The testimony of the older Salzburg annals for the year 920. In: German archive for research into the Middle Ages. Vol. 58 (2002), pp. 17–68, here: p. 54. ( online )

- ^ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 25.

- ↑ Johannes Laudage: King Konrad I in early and high medieval historiography. In: Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Konrad I .: On the way to the "German Reich"? Bochum 2006, pp. 340–351, here: p. 347.

- ↑ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 26.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff / Hagen Keller: Heinrich I and Otto the Great. New beginning on the Carolingian legacy. Vol. 1–2, Göttingen et al. 1985, pp. 60 ff.

- ↑ Ludger Körntgen: Kingdom and God's grace. On the context and function of sacred ideas in historiography and pictorial evidence of the Ottonian-Early Salian period. Berlin 2001, p. 81 ff.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Late Antiquity to the End of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024. (Gebhardt - Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte, 10th completely revised edition), Stuttgart 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Hagen Keller: Basics of Ottonian royal rule. In: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 22–33 (first published in: Karl Schmid (Ed.): Reich and Church before the Investiture Controversy, lectures at the scientific colloquium on the occasion of Gerd Tellenbach's eightieth birthday. Sigmaringen 1985, pp. 15–34).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state. Stuttgart et al. 2004.

- ^ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 27.

- ^ Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 71.

- ^ Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 72.

- ↑ Matthias Becher: Otto the Great. Emperor and Empire. A biography. Munich 2012, p. 92.

- ↑ Fragmentum de Arnulfo duce Bavariae . In: Philipp Jaffé (Ed.): Monumenta Germaniae Historica . I. Scriptores. Volume 17, 1861, p. 570.

- ↑ Thietmar I, 26

- ↑ Matthias Becher: Otto the Great. Emperor and Empire. A biography. Munich 2012, p. 86.

- ^ Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 78.

- ↑ DHI 10, p. 47; Wolfgang Giese. Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 78.

- ↑ Jörg Oberste: Saints and their relics in the political culture of the earlier Ottonian period. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, pp. 73-98, here: pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Liudprand, Antapodosis IV, 25th

- ↑ Jörg Oberste: Saints and their relics in the political culture of the earlier Ottonian period. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, pp. 73-98, here: p. 79; Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Franz Kirchweger: The shape and early history of the Holy Lance in Vienna. To the state of research. In: Gabriele Köster, Stephan Freund (Ed.): 919 - Suddenly King. Heinrich I. and Quedlinburg. Regensburg 2019, pp. 145–161; Caspar Ehlers: The Vexillum sancti Mauricii and the Holy Lance. Reflections on the strategies of Heinrich I. In: Gabriele Köster, Stephan Freund (Ed.): 919 - Suddenly King. Heinrich I. and Quedlinburg. Regensburg 2019, pp. 163–177; Caspar Ehlers: From the Carolingian border post to the central location of the Ottonen Empire. Recent research into the early medieval beginnings of Magdeburg. Magdeburg 2012, pp. 72-89.

- ↑ Jörg Oberste: Saints and their relics in the political culture of the earlier Ottonian period. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 37, 2003, pp. 73-98, here: p. 97.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Ottonians. Royal rule without a state . 2nd expanded edition, Stuttgart et al. 2005, p. 46.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Late Antiquity to the End of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024 . (Gebhardt - Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte, 10th completely revised edition), Stuttgart 2008, p. 122; Hagen Keller: Empire structure and conception of rule in the Ottonian-Early Salian times . In: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power . Darmstadt 2002, pp. 51–90, here: pp. 69–70 (first published in: Frühmittelalterliche Studien. Vol. 16, 1982, pp. 74–128, here: pp. 110 ff.).

- ↑ Gerd Althoff, Hagen Keller: Late Antiquity to the End of the Middle Ages. The time of the late Carolingians and Ottonians. Crises and Consolidations 888–1024 . (Gebhardt - Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte, 10th completely revised edition), Stuttgart 2008, p. 121.

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Empire structure and conception of rule in the Ottonian-Early Salian times . In: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power . Darmstadt 2002, pp. 51–90, here: p. 54 (first published in: Frühmittelalterliche Studien. Vol. 16, 1982, pp. 74–128, here: p. 79).

- ↑ Hagen Keller: Empire structure and conception of rule in the Ottonian-Early Salian times . In: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power . Darmstadt 2002, pp. 51–90, here: p. 60 (first published in: Frühmittelalterliche Studien. Vol. 16, 1982, pp. 74–128, here: p. 92.).

- ^ Hagen Keller: Basics of Ottonian royal rule . In: Ottonian royal rule. Organization and legitimation of royal power. Darmstadt 2002, pp. 22–33, here: p. 27 (First publication in: Karl Schmid (Ed.): Reich and Church before the Investiture Controversy, lectures at the scientific colloquium on the occasion of Gerd Tellenbach's eightieth birthday. Sigmaringen 1985, p. 15–34, here: pp. 25–26).

- ↑ Hagen Keller, Decision-making Situations and Learning Processes in the 'Beginnings of German History'. Otto the Great's 'Italy and Imperial Policy'. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 36 (2002), pp. 20–48, here: p. 26; Hagen Keller, On the seals of the Carolingians and the Ottonians. Documents as 'emblems' in communication between the king and his loyal followers. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 32 (1998), pp. 400–441, here: pp. 415 ff. Wikisource: Die Siegel der Deutschen Kaiser und Könige, Volume 5, p. 11, Heinrich I. Nr. 2 .

- ^ Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 152.

- ^ Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 154.

- ^ Wolfgang Giese: Heinrich I. founder of the Ottonian rule. Darmstadt 2008, p. 156.

- ↑ Widukind, Sachsengeschichte I, 32.