Gandersheim Monastery

The Gandersheim Monastery (from which today's town of Bad Gandersheim in Lower Saxony arose) was founded in 852 by the Saxon Count Liudolf , the progenitor and namesake of the Liudolfinger family. On a pilgrimage to Rome , he received the approval of Pope Sergius II and the relics of the holy Popes Anastasius and Innocentius necessary for the foundation for this project . The convent was initially located in the Brunshausen monastery until the monastery buildings and the collegiate church were completed .

The Gandersheim Monastery was a princely family monastery in terms of its character and, after its founding, soon flourished.

Collegiate life

The "Imperial Free Secular Reichsstift Gandersheim", as it officially called itself as an imperial abbey from the 13th century until its dissolution in 1810, was a community of unmarried daughters of noble families who wanted to lead a godly life in this women's monastery. The term “secular” is to be understood as the opposite of “monastic”, not as the opposite of “ecclesiastical” in today's sense. The residents were called "canons" or "canons"; after the Reformation they were also referred to as "canons". They had private property and did not take perpetual vows, so they could leave the pen at any time . The Ottonian and Salian emperors often stayed in Gandersheim with their entourage. So it was by no means a contemplative and remote life that the canons led. In addition to the memoria for the founding family, one of the tasks of the canons and thus of the monastery was the training and education of noble daughters. The pupils did not necessarily have to become canonesses themselves.

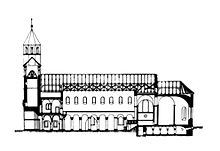

Collegiate church

In the collegiate church you can still see the Romanesque church building, which was expanded with Gothic additions. The collegiate church in Bad Gandersheim is a cruciform basilica with a western building equipped with two towers. It consists of a flat-roofed nave with a Saxon column change and two arched side aisles. The transept has a transverse rectangular crossing with roughly square transverse arms and the transverse rectangular choir bay adjoins it. There is a hall crypt under the crossing and the choir. The west building consists of two towers with a connecting building that has two floors. The westwork originally had a protruding vestibule with an upper floor, the so-called paradise.

The existing church building was started around 1100 and consecrated in 1168. Remnants of the previous buildings are integrated into the church. The building that can be visited today has been redesigned through restorations from the 19th and 20th centuries.

The bell of the church consists of 8 bells - 6 chime bells and 2 clock strikes and is therefore one of the largest in southern Lower Saxony.

history

founding

In 852 the Gandersheimer Stift was founded by Count Liudolf and his wife Oda. Liudolf is the progenitor of the Liudolfinger family , from whose family the Ottonian kings emerged. According to contemporary reports by contemporary Agius in his Vita Hathumodae and in the Hildesheim memorandum, the Hildesheim bishop Altfried , a cousin of Liudolf, had previously persuaded the couple to go on a pilgrimage to Rome with permission and an accompanying letter from King Ludwig the German in 845/46 to obtain permission from Pope Sergius II to establish a women's foundation. There they received the relics of the holy Popes Anastasius and Innocentius , who are the titular saints of the collegiate church to this day.

Initially, the convent was located in Brunshausen Monastery , with Hathumod , daughter of the couple who founded the monastery , taking over the management . The following two abbesses were also the daughters of Liudolf. Construction of the collegiate church in Gandersheim began in 856, and Bishop Wigbert von Hildesheim was able to consecrate the church to Saints Anastasius, Innocentius and John the Baptist in 881 . After 29 years, the convent was able to move into the new collegiate church.

As early as 877, the monastery was placed under the protection of the empire by King Ludwig the Younger and thus received extensive independence, also from the diocese of Hildesheim, which at that time was no longer a member of the Liudolfinger as a bishop. 919 confirmed King Henry I , the Imperial City of the pen. This close bond with the empire meant that the monastery had to accommodate the king on his travels through the empire. Various visits by kings are recorded.

The pen in Ottonian times

The founding of the monastery by the progenitor of the Liudolfinger (Ottonen) led to particular importance of the monastery also at the national level. Until the founding of the Quedlinburg Abbey in 936, Gandersheim was the most important Ottonian family abbey . The collegiate church was one of the burial places of the Ottonian family. In 940, the abbess in Gandersheim founded the Marienkloster , which was subordinate to the women's monastery .

Around 973 the monastery housed one of its most famous canonesses , Hrotsvit (Roswitha) von Gandersheim , who is considered the first German female poet; she wrote spiritual writings, historical poems and dramas . She expressed her admiration for Emperor Otto I in the "Gesta Ottonis" ("Otto's Deeds") , a work written in Latin hexameters on the family history and the political work of Otto the Great.

In the so-called "Great Gandersheim Dispute " at the turn of the 10th to the 11th century, the Hildesheim bishop filed claims for the monastery, which is why the canonies approached the Archbishop of Mainz because of the location on the unclear border between the dioceses of Mainz and Hildesheim . This competence was discussed at various synods, and only the full exemption privilege of Pope Innocent III. from June 22, 1206 released the monastery from the claims of the Hildesheim bishop. From then on the abbesses could call themselves " imperial duchesses ".

With the death of the last Salian king in 1125, the importance of the monastery declined and it became increasingly dependent on the sovereigns. The Guelphs in particular tried to expand their influence on the pen until the pen was dissolved. It was not possible for the monastery to establish its own sovereignty. The Brunswick dukes were able to secure the bailiwick through the monastery at the latest in the mid-1970s . They built a castle in Gandersheim at the end of the 13th century. Another way of influencing the monastery was to put related nobles on the abbess's chair. This was first achieved in 1402 with the abbess Sophia III, princess of Braunschweig-Lüneburg.

The Reformation

After an initial calm in the turmoil of the Reformation , the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel was occupied by troops of the Schmalkaldic League in 1542 and the Reformation was introduced. The reformers ignored the imperial immediacy of the monastery and ordered the evangelical worship service. Due to the absence of the dean, who ruled the monastery for the seven-year-old abbess, the canons were able to delay the execution. The citizens of Gandersheim had welcomed the reformers with joy, and on July 13, 1543 there was an iconoclasm in the collegiate church, during which the citizens and the mob destroyed altars. But Duke Heinrich the Younger was able to return, and the principality switched back to the Catholic faith. It partially replaced the damage and the church was rededicated. It was not until 1568 that the Reformation was finally introduced under Duke Julius of Braunschweig . The monastery and its own monasteries Brunshausen and Clus were dissolved, the Marienkloster and the Franciscan monastery. However, there were further disputes between the abbess of the monastery and the duke, because both wanted to expand their influence. It was not until 1593 that the disputes were finally settled in a contract.

The pen in the Baroque period

Under the abbesses Henriette Christine von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel and Elisabeth Ernestine von Sachsen-Meiningen , the women's foundation began to flourish again. They promoted the arts and sciences. Elisabeth Ernestine Antonie had the Brunshausen summer palace and the baroque wing of the abbey with the imperial hall built and provided the church with furnishings.

The abolition of the pen in 1802

In 1802 the monastery gave up its imperial immediacy in a treaty in order to avoid the threat of secularization . The monastery submitted to the state sovereignty of the House of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. The protracted struggle for imperial freedom in contrast to the Guelph dukes was over.

During the time of the French occupation, Gandersheim belonged to the Kingdom of Westphalia . Initially, the abbess who had fled had returned to the monastery with Napoleon's approval and was allowed to continue to reside there. After her death on March 10, 1810, there was no longer any choice of a successor. The monastery was dissolved, the possessions were added to the Westphalian crown domains and the members of the monastery were compensated.

Even after the end of the kingdom, the Duchy of Braunschweig was unwilling to restore the monastery.

The pen today

Today the monastery is used by the Evangelical Lutheran collegiate church of St. Anastasius and St. Innocentius. During restoration work in 1997, parts of the old church treasure, relics, textiles and reliquary containers were discovered. These have been exhibited as church treasures since March 2006 in the portal to history .

Abbess list

Personalities

- Hrotsvit (Roswitha von Gandersheim) (* around 935, † after 973), first German poet

- Johann Georg Leuckfeld (1668–1726), monastery researcher, historian, numismatist and biographer; initially worked as the Abbess's secretary

organ

The organ of the collegiate church was built in 2000 by the French organ building company Manufacture d'Orgues Muhleisen (Strasbourg). The award-winning instrument has 50 stops , including seven transmissions from the main work into the pedal and an extended pedal stop. The playing and stop actions are mechanical.

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Pairing :

- Normal coupling: II / I, I / P, II / P.

- Super octave coupling:

- Sub-octave coupling:

Fixed combinations (p, f, tutti), 256-fold typesetting system , crescendo roller . I / P - II / P - III / P Manual coupling I / II - III / I - III / II 8 '- III / II 16' Double registration system mechanical + electrical (15,000 combinations)

literature

- Hans Goetting : The imperial canonical monastery Gandersheim . In Max Planck Institute for History (ed.): Germania sacra: historical-statistical description of the Church of the Old Kingdom . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1973, ISBN 3-11-004219-3 .

- Ernst Andreas Friedrich : If stones could talk. Landbuch-Verlag, Hannover 1989, ISBN 3-7842-0397-3

- Helga Wäß: Form and Perception of Central German Memory Sculpture in the 14th Century. Catalog of selected objects from the High Middle Ages to the beginning of the 15th century . Volume 2. Tenea, Bristol / Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-86504-159-0 , p. 222 f.

- Martin Hoernes, Hedwig Röckelein (eds.): Gandersheim and Essen. Comparative studies on Saxon women's colleges . In: Essen research on the women's foundation . Volume 4. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2006, ISBN 3-89861-510-3 .

- Portal to history: rediscover treasures! Selection catalog, ed. by Martin Hoernes and Thomas Labusiak , Delmenhorst 2007.

- Miriam Gepp: The collegiate church in Bad Gandersheim. Memorial place of the Ottonians. Edited by Thomas Labusiak, Munich 2008

- Birgit Heilmann: Heiltum becomes history. The Gandersheim reliquary in the post-Reformation period. Edited by Thomas Labusiak and Hedwig Röckelein, Regensburg 2009 (studies on the women's monastery in Gandersheim and its own monasteries, volume 1)

- Birgit Heilmann: Catholic remains or traditional treasure? . The evangelical canonical monastery Gandersheim and its medieval legacy. in: Women's Convents in the Age of Confessionalization , Klartext Verlag, Essen 2010, ISBN 978-3-8375-0436-1 .

- Jan Friedrich Richter: Gothic in Gandersheim. The wood carvings of the 13th to 16th centuries. Edited by Thomas Labusiak and Hedwig Röckelein, Regensburg 2010 (studies on the women's monastery in Gandersheim and its own monasteries, volume 2)

- Christian Popp: The treasure of cannonies. Saints and relics in the women's monastery in Gandersheim. Edited by Thomas Labusiak and Hedwig Röckelein, Regensburg 2010 (studies on the women's monastery in Gandersheim and its own monasteries, volume 3) ( review )

- Amalie Fößel : Ottonian abbesses as reflected in the documents. Opportunities for Sophia von Gandersheim and Essen to influence the politics of Otto III. , in: Thomas Schilp (ed.): Women build Europe. International links of the Essen women's monastery . Klartext Verlag, Essen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8375-0672-3 , pp. 89-106.

- Ernst Andreas Friedrich: The cathedral of Gandersheim , p. 102-105, in: If stones could talk. Volume I, Landbuch-Verlag, Hannover 1989, ISBN 3-7842-03973 .

Web links

- Permanent exhibition in the Gandersheim collegiate church

- Description of the Gandersheim Abbey on the Lower Saxony monastery map of the Institute for Historical Research

Individual evidence

- ↑ More about the Muhleisen organ (PDF file)

Coordinates: 51 ° 52 '13.4 " N , 10 ° 1' 33.9" E