Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel

|

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel | |

| coat of arms | |

|

|

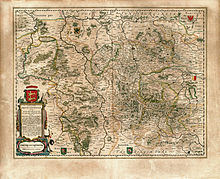

| map | |

|

|

| The Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel in 1789 | |

| Alternative names | Duchy of Brunswick |

| Arose from | until 1269 the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

| Today's region / s |

DE-NI , DE-ST

|

| Capitals / residences | Wolfenbüttel , Braunschweig |

| Dynasties | Guelphs |

| Language / n |

Low German , German

|

| Incorporated into |

Duchy of Braunschweig (since 1815)

|

The Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel was a part of the Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg , whose history was characterized by numerous divisions and reunions. Various sub-dynasties of the Guelphs ruled Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1806. The successor state of the Duchy of Braunschweig was established by the Congress of Vienna in 1814 .

history

middle Ages

After Otto the child , grandson of Henry the Lion , the former allodial his family (the present-day eastern in the area of Lower Saxony and northern Saxony-Anhalt located) by Emperor Frederick II. On August 21, 1235 as a fiefdom under the name Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg had received , the land was divided up by his sons in 1267/1269.

Albrecht I (also called Albrecht the Long) (1236–1279) received the areas around Braunschweig - Wolfenbüttel , Einbeck-Grubenhagen and Göttingen-Oberwald . He founded the old house of Braunschweig and laid the foundation for what was later to be known as the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. His brother Johann (1242–1277) inherited the land around Lüneburg. He founded the old house in Lüneburg. The city of Braunschweig remained a common territory.

In the Braunschweig area (Wolfenbüttel) there were further divisions in the following decades. So the lines of Grubenhagen and Göttingen split off from time to time.

In the meantime, the dukes were tired of the constant arguments with the citizens of the city of Braunschweig and in 1432 they moved their residence to the moated castle Wolfenbüttel , which was about twelve kilometers south of Braunschweig in a swampy valley on the Oker River . The castle of the Braunschweig-Lüneburg dukes that was built here became - in conjunction with that of the ducal chancellery, the consistory , the courts and the archive - the control center of a huge area from which the Wolfenbüttel-Braunschweig part of the entire duchy was governed. For a long time, the principalities of Calenberg-Göttingen and Grubenhagen , the Prince Diocese of Halberstadt , large areas of the Prince Diocese of Hildesheim and the Counties of Hohnstein and Regenstein , the Lords of Klettenberg and Lohra as well as parts of Hoya on the Lower Weser were under their control . The importance of the court corresponded to the number of craftsmen needed. For these, for citizens and ducal institutions, hundreds of half-timbered buildings were built , initially disorganized, later aligned with ducal orders and protected against fire. In 1432 the lands between Deister, Weser and Leine , which had been acquired by the (meanwhile) Middle House of Braunschweig, split off as the Principality of Calenberg under Wilhelm the Victorious , while Heinrich the Peaceful received places between Oker and Aller . At the height of urban development, Heinrichstadt was followed by Auguststadt in the west and Juliusstadt in the east. Further mergers and further divisions followed.

After the now twelfth division in 1495, in which the Principality of Braunschweig-Calenberg-Göttingen was again broken down into its components, Erich the Elder received places between the Weser and Leine, Principality of Calenberg, Duke Heinrich the Elder received the Land of Braunschweig for the now the new residence Wolfenbüttel was named, plus an area strip west of the Harz with Seesen , Stauffenburg , Gandersheim , Greene , Lüthorst , Hohenbüchen , Homburg , Stadtoldendorf , Amelungsborn , Everstein and Fürstenberg . The name of the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel prevailed.

Early modern age

The reigns of the dukes Heinrich the Younger , Julius and Heinrich Julius followed , under whose rule the Wolfenbüttel residence was expanded and the principality should gain importance throughout Germany.

From 1500 Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel became part of the Lower Saxony Imperial Circle .

From 1519 to 1523 there were armed conflicts with the Principality of Hildesheim , which had already been an opponent in the Battle of Dinklar , and the Principality of Lüneburg in the Hildesheim collegiate feud , which resulted in large land gains. In 1643 the Hildesheim Recess came about, in which the return of these gains was agreed.

In 1571 the castle and the town of Calvörde became part of the principality through Duke Julius . After the death of Erich II in 1584, Calenberg-Göttingen was ruled again by the Wolfenbüttel line of the Guelphs.

During the Thirty Years' War Wolfenbüttel was the strongest fortress in Northern Germany, but survived the war only badly damaged. The Wolfenbüttel line died out during the war in 1634 with Friedrich Ulrich .

In 1635, Duke August the Younger from the Lüneburg-Dannenberg branch line took control of the principality and founded the New House of Braunschweig. During his reign, Wolfenbüttel reached its highest cultural boom. One of his greatest achievements was the establishment of the Herzog August Library , which at the time was the largest in Europe. In 1671, an old dream of the Guelph Dukes came true: the joint armed forces of the partial dynasties were able to recapture the city of Braunschweig and integrate it into their domain.

After the partial dynasty died out again in 1735, another branch line had to step in, this time the Braunschweig-Bevern line founded in 1666.

In the years 1753/1754 the residence of the Dukes of Wolfenbüttel was moved back to Braunschweig, to the newly built Braunschweig Palace .

The urban independence of Braunschweig, which had existed since the 15th century, was thus lost. The Duke thus carried out what was the trend, and it didn't matter that the new palace at the “ Grauen Hof ”, which Hermann Korb had begun in 1718, was not yet finished. The effects on Wolfenbüttel were catastrophic, as can be seen from the half-timbered buildings that were built later. 4,000 citizens followed the ducal family and Wolfenbüttel's population fell from 12,000 to 7,000. Only the archive , the church office and the library remained as a bridge. From Braunschweig one heard ridicule: Wolfenbüttel had degenerated into a "widow's seat".

The wide garden areas in front of the three gates (Herzogtor, Harztor, Augusttor) were former gardening on a leasehold left. As a result, canning factories emerged, which shaped Wolfenbüttel into the 20th century. In front of the Herzogtor, the number of gardens grew, which eventually extended to the Lechlumer Holz. On its southern edge, the Lustschlösschen Antoinettenruh , built in 1733 instead of a garden house , was a work of the architect Hermann Korb, who was so important for Wolfenbüttel . Wolfenbüttel became the city of schools, in 1753 the teachers' seminar was founded, which began in the orphanage and later moved to the building of today's Harztorwall school.

Politically, Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel became one of Prussia's closest allies. While shortly before the Habsburg emperor was still the most important point of reference due to a marriage policy, the Wolfenbüttel Welfen House was closely tied to the Hohenzollern family through the marriage of the Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich to Elisabeth Christine . The marriage was arranged by Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia and Ferdinand Albrecht. It formed the basis for the later “brotherhood in arms” between the small state and Prussia. In the Seven Years' War in particular , numerous Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel officers served in high positions in the Prussian army . The regiments of the principality covered with the Allied Army in the west Prussia and above all the allied electorate Braunschweig-Lüneburg . The Duke of Braunschweig and Lüneburg, Hereditary Prince Ferdinand of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, was an outstanding representative of the military ties between Braunschweig and Prussia .

In Carl's I era, great achievements were made in the cultural and scientific fields: the theater was promoted and education promoted. In 1753 the ducal art and natural history cabinet - the forerunner of the Natural History Museum - was founded. The extensive collections were put together by the Brunswick dukes. This project was funded by Abbot Jerusalem , founder of the Collegium Carolinum . No longer Wolfenbüttel, but Braunschweig now experienced a cultural boom.

Duke Carl I died in 1780. His eldest son, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, succeeded him . In August 1784, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was on a political mission in Braunschweig when he accompanied his Duke Carl August as a Weimar minister : In a situation in which the political situation between Austria and Prussia had once again come to a head, some Germans were planning Small and medium-sized states as a balancing force a princes league ; the Duke of Brunswick was to be won over for him, which was also achieved on August 30th.

Napoleonic era and transition to the Duchy of Braunschweig

By the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of February 25, 1803, the Principality received the secularized Gandersheim and Helmstedt monasteries . In 1806, Duke Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand was fatally wounded as a Prussian general in the battle of Auerstedt . After a short interlude, Braunschweig was occupied by the French from 1807 to 1813 and part of the Kingdom of Westphalia .

After the end of Napoleonic rule, the country was rebuilt under the name of the Duchy of Braunschweig .

Branch line in Bevern

The Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern emerged from an inheritance dispute between Ferdinand Albrecht I and his brothers. Ferdinand Albrecht was awarded Bevern Castle near Holzminden in 1667 . He - and subsequently his son Ferdinand Albrecht II - were princes of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern. In 1735, Ferdinand Albrecht II took over the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, so that the Principality was again part of the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel.

Administrative structure

The Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel was divided into 118 offices in 1793. Of these, 11 were municipal court offices, 32 main offices, 19 monastery courts, 8 princely courts, 22 aristocratic courts with higher jurisdiction , 21 noble courts without higher jurisdiction, 4 glebasten courts without higher jurisdiction, and 1 noble commandery court. All of these areas had the competences of an office and seat and vote in the Braunschweigische estates assembly , although they were of very different size, legal form and importance.

The offices were divided into two main areas (northern and southern offices) and these were divided into two main districts each. The northern offices included the Wolfenbüttel district around the capital and the royal seat, as well as the Elm district around Helmstedt with the isolated office Calvörde . The southern offices were formed by the Harz District and the Weser District .

There was also the office of Thedinghausen, located outside Verden , and the principality of Blankenburg, located in the southeastern Harz . From 1731 the principality was permanently connected with Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel in personal union, but remained an independent imperial estate until 1805. A special constitutional feature was the Lower Harz Communion District , which was temporarily administered together with the Electorate of Hanover .

Agrarian Constitution

According to Bornstedt, serfdom was revoked with the “ Receß of May 17, 1433” by Heinrich the Friedsamen . In Bornstedt's opinion, Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel is the first principality in the Holy Roman Empire in which serfdom was abolished.

The receipt stipulated that all arbitrariness in the levies of the Meier was dropped , especially in the case of the death of the farmers . The owner of the Meiergut remained the landlord. But now the Meier could also resign. The prohibition of arbitrariness, however, usually meant that the Meier family did not withdraw when the contracts expired or when the farmer died, so the demolition did not take place. In 1563 it was decreed by Heinrich the Younger that every six years Meier and landlord had to act on the continuation of the farm, which was later extended to nine years. With his state parliament farewell in 1597, Duke Heinrich Julius made the farms hereditary.

With the Brunswick order of replacement of the Duchy of Brunswick (the " legal successor ") of December 20, 1834, the dependency of the farmers was abolished. The peasants could buy their way out, they could borrow the money from the ducal loan agency. The separation followed at the end of the 19th century .

Population development

| year | Residents | comment | source | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1663/ 1664 |

63,000 to 67,000 |

47,691 residents liable to tax . |

|

|

| 1760 | 153.980 | |||

| 1788 | 184,708 | |||

| 1793 | 191.713 | |||

| 1799 | 200.164 | |||

| 1804 | 208,000 |

See also

- List of the rulers of the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel

- Tribe list of the Guelphs

- Brunswick Army

- List of the Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel regiments of the early modern period

- Commemorative coin "on the separation of brotherly unity" . The political situation that led to the end of community government in 1702 is unique in its extensive historical representation on one coin.

literature

- Wilhelm Havemann : History of the Lands Braunschweig and Lüneburg. 3 volumes. Emphasis. Hirschheydt, Hannover 1974/1975, ISBN 3-7777-0843-7 (original edition: Verlag der Dietrich'schen Buchhandlung, Göttingen 1853-1857, books.google.de ).

- Thomas Klingebiel: A stand of its own? Local officials in the early modern period. Studies on state formation and social development in the Hildesheim Monastery and in the older Principality of Wolfenbüttel. Hannover 2002, ISBN 3-7752-6007-2 .

- Werner Knopp : In the shadow of the big brother: Braunschweig and Prussia in Frederician times . In: Gerd Biegel (Ed.): Braunschweiger Museum Lectures . No. 1 . Braunschweig 1986.

- Hans Patze (term): History of Lower Saxony. 7 volumes. Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hanover 1977– (= publications of the Historical Commission for Lower Saxony and Bremen. 36) - ( volume overview ).

- Gudrun Pischke: The divisions of the Guelphs in the Middle Ages. Lax, Hildesheim 1987, ISBN 3-7848-3654-2 .

- Georg Hassel and Karl Bege : Geographical-statistical description of the principalities of Wolfenbüttel and Blankenburg. Volume 1 / Volume 2. Culemann Braunschweig 1802/1803

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Horst-Rüdiger Jarck, Gerhard Schildt (Ed.): Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. A region looking back over the millennia . Braunschweig 2000, p. 237.

- ↑ Cf. Werner Knopp: In the shadow of the big brother: Braunschweig and Prussia in Frederician times . In: Gerd Biegel (Ed.): Braunschweiger Museum Lectures . No. 1 . Braunschweig 1986.

- ^ Johann Georg Heinrich Hassel and Karl Friedrich Bege: Geographical-statistical description of the principalities of Wolfenbüttel and Blankenburg. In: Volume 1. Retrieved July 18, 2020 .

- ^ Johann Georg Heinrich Hassel and Karl Friedrich Bege: Geographical-statistical description of the principalities of Wolfenbüttel and Blankenburg. In: Volume 2: p. 313-327 (PDF pages 317-331). Retrieved July 18, 2020 .

- ↑ G. Hassel, K. Bege: Geo-statistical description of the principalities of Wolfenbüttel and Blankenburg. 2 volumes. Braunschweig 1802/1803

- ^ Wilhelm Bornstedt : From the story of Rautheim an der Wabe , 1977, p. 28 ff.

- ↑ Ulrich Brohm: The handicraft policy of Duke August the Younger of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (1635–1666). Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, p. 40, ISBN 3-515-07368-X .

- ^ A b c d Georg Hassel : Geographical-statistical description of the principalities of Wolfenbüttel and Blankenburg . Volume 1. Friedrich Bernhard Culemann, Braunschweig 1802, pp. 54–55

- ↑ Georg Hassel: Statistical outline of all European states . Vieweg, Braunschweig 1805, p. 78.