Prussian Army

The Prussian Army (full form: Royal Prussian Army , from 1644 to 1701 Electoral Brandenburg Army ) was the army of the Prussian state from 1701 to 1919. It emerged from the standing army of Brandenburg-Prussia that had existed since 1644 . In 1871 she joined the German Army and was dissolved in 1919 as a result of the defeat of the German Empire in the First World War .

The military strength of this army was a prerequisite for the development of Brandenburg-Prussia into one of the five major European powers of the 18th and 19th centuries. Their defeat at the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars in 1806 marked a turning point in their history. They introduced a fundamental modernization under the leadership of Gerhard von Scharnhorst , which completely changed the army. Historians therefore speak of the Old Prussian Army (1644–1807) and the New Prussian Army (1807–1919).

After the reform, the Prussian army took part in the Wars of Liberation between 1813 and 1815 and played a decisive role in the liberation of the German states from French rule. During the period from the Congress of Vienna to the German Wars of Unification , the Prussian army became an instrument of restoration and contributed significantly to the failure of the nation-state-bourgeois revolution of 1848 .

The military successes of the Prussian army in the wars of unification were decisive for the victory of the allied German troops over France. In the German Empire it formed the core of the German army. The constitution of 1871 provided for the Prussian army units to be integrated into the units of the German army during times of war. In the First World War, the Prussian army was therefore not legally independent. After the end of the war, Germany had to reduce its land forces to 100,000 men in accordance with the provisions of the Versailles Treaty . The existing state armies of Prussia, Bavaria , Saxony and Württemberg were dissolved.

One of the most important features of the Prussian army, which has shaped its image to the present day, was its significant role in society. Their influence in the civilian part of the state shaped Prussia as the epitome of a militaristic state (cf. Militarism in Germany ).

history

In its time as a standing army, the Prussian Army was always subjected to processes of change of varying intensity, as a result of which the army was regrouped, realigned or fundamentally reformed in order to bring the armed power back into harmony with newly emerging political and social conditions. The dynamics of technical, scientific and industrial progress as well as demographic and intellectual developments almost always affected the army as well. These are indications of enormous interactions between the military, society, economy and technology.

For this reason, the political leaderships of the different epochs felt compelled to redefine the tasks and role of the military in state and society and to legitimize them. The respective reform discourses and reform projects of their time were embedded in pan-European developments that the army officials faced and tried to find solutions. In a timeline from around 1650 to 1910, there were periods of rapid change in the army, which rose and ebbed again with the economy, only to be replaced by a new phase of evolution after the reform goals had been implemented.

The fundamental evolutionary stages of the Prussian army were:

- Transition from the temporary mercenary army to the standing army approx. 1650 to 1680

- Professionalization, standardization, disciplining and institutionalization from approx. 1680 to 1710

- Expansion and maintenance of a first-rate army in Europe from approx. 1710 to 1790

- Replacement of the Army of the Cabinet Wars by a People's Army from around 1790 to 1820

- Restoration of the army as an instrument of rule and quasi praetorian guard of the king from approx. 1820 to 1850

- Transition to a modern mass army with industrialized warfare from approx. 1850 to 1910

Under the Great Elector (1640–1688)

(drawing by Maximilian Schäfer )

The beginnings of the Prussian army as a standing army date back to the reign of the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm , the Great Elector (1640 to 1688). At a meeting of the Privy Council on June 5, 1644, it was decided to set up a standing army. Before that, Brandenburg had set up a paid mercenary army in the event of war , which was disbanded after the war. This procedure, as the course of the Thirty Years' War showed , was no longer appropriate.

The growth of the army required massive recruits in Brandenburg. The necessary numbers of recruits could only be raised with coercive measures. The recruiting undertaken for the new army brought together 4,000 men in Kleve alone. In the Duchy of Prussia 1,200 regular soldiers and around 6,000 militias could be raised. In the Kurmark the balance was much lower due to the decimated population. Only 2,400 soldiers could be raised. Also to be counted were the 500 musketeers of the elector's bodyguard. As early as 1646, two years after its foundation, the electoral army consisted of 14,000 men, 8,000 regular soldiers and 6,000 armed militias.

It was also Friedrich Wilhelm who enforced the essential principles of the later Prussian army:

- Connection of the advertising system with the compulsory service of local farmer sons,

- Recruiting officers from the local nobility,

- Financing of the army through the electoral domain income .

In the Second Swedish-Polish War (1655–1660) the Brandenburg-Prussian army already reached a total strength of around 25,000 men, including garrison troops and artillery . Led by the Great Elector personally, 8,500 Brandenburgers and 9,000 Swedes defeated 40,000 Poles in the Battle of Warsaw . In this war, Friedrich Wilhelm obtained sovereignty in the Duchy of Prussia in the Treaty of Oliva in 1660 .

Friedrich Wilhelm and his Field Marshal Derfflinger defeated the Swedish army in the Swedish-Brandenburg War in the Battle of Fehrbellin in 1675 . The electoral army then drove the Swedes out of Germany and later from Prussia during the hunt over the Curonian Lagoon in 1678. Friedrich Wilhelm owed his nickname The Great Elector to these victories .

During the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm, the army temporarily reached a peacetime strength of 7,000 and a war strength of 15,000 to 30,000 men.

Under Elector and King Friedrich I (1688–1713)

At the beginning of the Imperial War with France in 1688, Elector Friedrich III. For the first time it was suggested that in addition to recruiting by individual regiments, his local, Kurbrandenburg regional authorities within the Reich had to raise some of the recruits to replace men. Since then, the army team has mostly been supplemented by forcibly recruited residents and less by recruited foreigners.

In 1701 Friedrich III crowned himself. to the king in Prussia. As a result, his army was called Royal Prussian and no longer Kurbrandenburg. In the course of the 18th century the name Prussia was transferred to the entire Brandenburg-Prussian state, both inside and outside the empire. The price that Prussia had to pay for the imperial recognition of the rise of rank was participation in the War of the Spanish Succession . The Prussian troops took part in the battles of Höchstädt , Ramillies , Turin , Toulon and Malplaquet , among others . During the Spanish War of Succession, Frederick I divided his troops into the various theaters of war. 5,000 men were sent to the Netherlands and 8,000 soldiers to Italy . Thus about 3/4 of the Prussian troops were in the service of the Allies. Even at that time the Prussian troops had a reputation for being the best in Europe. The associated financial burden - together with his luxurious lifestyle - forced the king to temporarily reduce the army to 22,000 men after the end of the war. It was the last reduction in the Brandenburg-Prussian army.

In 1692 a military tribunal was established to raise the soldiers' discipline.

Around 1700, the Prussian army began to dress soldiers more and more uniformly. Uniform clothing brought several advantages: Firstly, the uniform filled the soldiers with a certain spirit of corps. Second, it was easier to distinguish between friend and foe. Thirdly, mass production made it cheaper to dress soldiers. In the Prussian army, blue was the dominant basic color.

Under the soldier king Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713–1740)

The army gained special importance since the reign of the soldier king Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713 to 1740). The army enjoyed priority in what was now the Kingdom of Prussia in such a way that the state without the army was unthinkable.

It was also Friedrich Wilhelm I who introduced the first statutory recruitment system ( cantonal regulations ) in 1733 , which was to last until 1814. The aim was to end the army's often violent recruiting. The cantonal regulations forced all male children to be registered for military service. In addition, the country was divided into cantons, each of which was assigned a regiment from which it recruited conscripts. The period of service of a cantonist (conscript) was usually two to three months a year. The rest of the year the soldiers were able to return to their farms. Urban citizens were often exempt from military service, but had to provide quarters for the soldiers.

The army was expanded gradually. In 1719 there were already 54,000, in 1729 more than 70,000, in 1739 over 80,000 men (for comparison: in 1739 Austria had 100,000 men, Russia 130,000 men, France 160,000 men under arms). Prussia was "as a dwarf in the armor of a giant". In the ranking of the European states in 13th place, it had the third or fourth strongest military power. Overall, Prussia spent 85% of its government spending on the army at this time. What was still lacking in equality with the great power armies was made up for by the quality of the training.

The royal regiment of the Lange Kerls in Potsdam served as teaching and model troops . This regiment originated from the soldier's hobby of the "soldier king". The king had recruiting officers sent out in all directions in Europe in order to get hold of all the tall men over 1.88 meters there were. This king's passion for “tall guys” had a practical sense, as they could use feet with longer runs. The ramrod could be pulled out of the muzzle loader and inserted more quickly. This allowed them to shoot more accurately and further in battle. A decisive advantage over other armies. The regiment consisted of three battalions with 2,400 men.

Since the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm I, the officer corps consisted essentially of members of the nobility . However, he had to be systematically forced to join the army. Friedrich Wilhelm I forbade the nobility to serve in an army other than the Prussian army. Furthermore, he issued an order that the nobility had to give their sons between the ages of 12-18 years for training and education in the newly created cadet corps . Thus the nobility, like the simple peasants or bourgeoisie, was made subject to service. In principle, long-serving and particularly proven non-noble NCOs were appointed officers in peacetime only in exceptional cases.

Although Friedrich Wilhelm I went down in history as the soldier king, he led his army into war only once during his entire term of office, namely during the Great Northern War in the siege of Stralsund (1715) .

Under Frederick the Great (1740–1786) until the defeat of 1806

After the reorganization of the Prussian infantry, the successor to Friedrich Wilhelm I, Frederick the Great (1740–1786), began the Silesian Wars six months after the accession to the throne and, from a European perspective, the overarching War of the Austrian Succession . The Prussian army, led by Field Marshal Kurt Christoph von Schwerin , defeated the Austrian troops on April 10, 1741 in the Battle of Mollwitz and thus decided the first Silesian War in favor of Prussia.

Austria tried to recapture Silesia in the Second Silesian War . However, the Prussian army had increased by nine field battalions, 20 squadrons of hussars (including 1 squadron of Bosniaks ) and seven garrison battalions during the two years of peace . In addition, a new regulation was introduced for the cavalry and infantry on June 1, 1743, in which the experiences of the First Silesian War were taken into account. Austria and Saxony were defeated in the Battle of Hohenfriedeberg in 1745. Especially the hussars (also called Zietenhusars) under the leadership of General Zieten were able to distinguish themselves in this battle.

Austria then allied with France in the course of the diplomatic revolution (1756); Austria, France and Russia stood together against Prussia. Frederick the Great attacked his enemies preventively with an army of 150,000 men, which triggered the Seven Years' War . Although outnumbered, the Prussian army achieved notable victories in 1757 in the Battle of Roßbach and the Battle of Leuthen . In contrast, the Prussian forces were clearly defeated in the Battle of Kunersdorf in 1759 .

With dwindling physical reserves, small warfare in particular became increasingly important. In order to be able to compensate for the superiority of the Austrians ( border guards , Pandurs ) and Russians ( Cossacks ) here, Friedrich set up free battalions (“Three blue and three times the devil, an exekaberes shit!”) And even attacked the military with the formation of militia units Development of the Wars of Liberation .

The offensively oriented Frederick II was an advocate of the lopsided order of battle , which required considerable discipline and mobility of the troops. Most of his armed forces were concentrated on the left or right wing of the enemy. He let these advance in stages around the opposing flank. In order to cover up the train, Friedrich attacked the enemy line with further units head-on at the same time, in order to keep the enemy busy so that he did not have time to adjust his formation to the train. If the troops were positioned close to the flank of the enemy, the Prussian units could gain local superiority, penetrate the flank and roll up the enemy ranks from the side, thereby blowing up the formation. Although this tactic failed at Kunersdorf, it was used with great success in the Battle of Leuthen and the Battle of Roßbach. Towards the end of the Seven Years' War, Frederick II began to work out new tactics to replace the oblique battle line.

The Prussian defeat seemed inevitable, but Frederick the Great was saved by the miracle of the House of Brandenburg . The sudden death of Tsarina Elisabeth led to Russia's withdrawal from the war and to the rescue of Prussia. The possession of Silesia was confirmed in the Treaty of Hubertusburg (1763). At the end of Friedrich's reign (1786) the Prussian army had become an integral part of Prussian society. The Prussian army had about 193,000 soldiers.

Frederick the Great's successor, his nephew Friedrich Wilhelm II , hardly cared about the army. He had little interest in military questions and transferred responsibility for them mainly to Karl-Wilhelm Ferdinand , Duke of Braunschweig, to Wichard von Möllendorff and Ernst von Rüchel . In the period that followed, the army lost its military quality standard. Led by aging veterans of the Silesian Wars and poorly equipped, it could not keep up with the French army of the Napoleonic Wars.

From the army reform under Scharnhorst to the Wars of Liberation

The year 1806 brought a great change. The army, which until then consisted of conscripts and recruits, was defeated by the French army in the battle of Jena and Auerstedt . As a result of this defeat in the Peace of Tilsit in 1807, Prussia lost large parts of its territory and the army was limited to a strength of 42,000 men. Then Gerhard von Scharnhorst began the army reform .

August von Gneisenau , Carl von Clausewitz and other officers helped him reorganize the army. Scharnhorst opened the army to commoners with the aim of reinforcing the concept of achievement before the birthright of the nobility. This was particularly true of the officer corps. The bourgeoisie and the nobility were to form a new class of officers, that of the scientifically educated officer.

He advocated the concept of mass levy ( French levée en masse ) for the Prussian army in order to strengthen the limited Prussian army; then the Landwehr was created as a militia, which reached a strength of 120,000 men. After the reorganization was completed in September 1808, only 22 of the 142 Prussian generals of 1806 were serving, of the remaining 6 had died and 17 had left on punishment. Scharnhorst introduced the Krümpersystem in that up to a third of the respective soldiers were given leave and replaced by new recruits. This did not circumvent the stipulated maximum strength of 42,000 men and yet created a reservoir of men fit for service.

Scharnhorst also reformed the catalog of punishments. Flogging with a stick and running the gauntlet were banned, instead the new system only provided for arrest sentences. In the case of minor offenses, the penalties were graded accordingly, from re-exercise to labor service or the police station. This reform of the disciplinary penalties was necessary so that the concept of the people's army could work. The image of the soldier pressed into service, threatened with desertion and who had to be kept in the army by force, was to be replaced. Instead, the soldier should become a respected, honorable profession that fulfills its duties voluntarily. The success of this reform policy enabled Prussia a few years later to successfully participate in the wars of liberation .

The alliance treaty of February 24, 1812 obliged Prussia to provide an auxiliary corps of 20,000 men (14,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, 2,000 artillery with 60 cannons) for the war against Russia. This auxiliary corps was assigned to the 27th Division of the Xth Army Corps of the Grande Armée . The participating battalions and regiments were selected by drawing lots. The Prussian Auxiliary Corps (Yorcksches Korps) did not fall into the downfall of the Great Army on their way to Moscow and back, as it was deployed on the left flank in Courland. On the other hand, on the direct orders of Napoleon, two parent companies of the Prussian artillery brigade of the French Guards Artillery were illegally attached as train soldiers. These came as far as Moscow and went down there in the wake of the Guards artillery. There were almost no returnees from these two units. Despite a few skirmishes, Yorck's auxiliary corps was largely spared and, after an addition in January / February 1813 in Tilsit, formed the core of the first troops in the liberation struggle against France.

After the defeat of the Grande Armée in Russia, the armistice between Prussia and Russia was signed on December 30, 1812 near Tauroggen (Tauragė in Lithuania) by the Prussian lieutenant general Graf Yorck and von Diebitsch , general of the Russian army. Yorck acted on his own initiative without orders from his king. The convention said that Yorck should separate his Prussian troops from the alliance with the French army. In Prussia this was seen as the beginning of the uprising against French rule.

When the people were called on March 17, 1813 to fight for freedom, 300,000 Prussian soldiers (6 percent of the total population) were standing by. General conscription was introduced for the duration of the war, and from 1814 it also applied to peacetime. In addition to the standing army and the Landwehr, the Landsturm Edict of April 21, 1813 created a third contingent, the so-called Landsturm , which could only be used in the event of a defense and was the last contingent. At the end of 1815 the Prussian army had a strength of 358,000 men.

From the Congress of Vienna to the Wars of Unification

After the Congress of Vienna , a large part of the Landwehr and part of the line army were demobilized, so that the strength sank from 358,000 men in 1815 to around 150,000 men in 1816. In the years between 1816 and 1840 (death of Friedrich Wilhelm III. ) The military budget was limited by various austerity measures as a result of a structural budget deficit in the Prussian state. In 1819 the military share of the state budget was 38%, in 1840 it was 32%.

After the wars of liberation, many of the military reforms, some of which were idealistic, faded. This went hand in hand with the general restoration of the old conditions. The Landwehr was unable to take the place that was intended for it next to the standing army, as its military value was too limited. The officer's profession was still open to the bourgeoisie, but the aristocratic class was obviously preferred. So the Prussian army again became a refuge for conservative, aristocratic and monarchical sentiments. During the revolution of 1848 , the Prussian army was the instrument that ensured that the revolution failed and the structures of rule remained intact. Although Prussia had become a constitutional monarchy with the constitution of 1850 , the soldiers were sworn in on the person of the ruler and not on the constitution.

In 1859 Albrecht von Roon (Minister of War and the Navy) was commissioned by Wilhelm I to carry out an army reform in order to adapt to the changed circumstances. The reasons for the renewed need for reform lay in technical progress and the sharp increase in population (the size of the army, as in 1816, was 150,000 men). Furthermore, after two chaotic mobilizations in 1850 and 1859, it became clear that the Landwehr could be used for a war of defense, but of limited value in a war of aggression.

His goal was to expand the Scharnhorst system and create an armed nation. In order to achieve this, he proposed in his army reform to maintain conscription for three years, to increase the number of recruits by 1/3, to enlarge the field army and to reduce the landwehr. Due to a constitutional conflict that this triggered , the reform was not adopted by the North German Confederation until 1866. As the Landwehr was pushed back further, the process of "de-bourgeoisie" of the army was pushed forward.

In addition, the outdated equipment was modernized during this period (1850s and 1860s). The Prussian army was the first to equip the entire infantry with rifled rifles, the fuse breech-loaders . Likewise, the previous smooth-bored guns were gradually replaced by new guns with rifled gun barrels . In May 1859 ordered General War Department at Alfred Krupp 300 cannons from cast steel (against the background of the conflict between Austria, France and Italy → Sardinian War ). In view of this major order, Krupp rejected his idea of stopping cannon production and development.

The strong drill ( drill and formal service ), which still came from Friedrich Wilhelm I , was replaced by a better training system; Combat exercises and target shooting became more important. This increased the army's combat strength. The long-time neglected professional training of officers was brought back to a high level; the ordinances for senior troop leaders of June 24, 1869 by Helmuth von Moltke were groundbreaking . The Prussian army became one of the most powerful of its time. This was also evident in the German-Danish War (1864) and in the German War (1866).

In the empire

With the establishment of the German Empire in 1871, the Prussian Army became a core component of the German Army , and the Baden Army was incorporated into it as the XIV Corps . In times of peace, the Prussian army legally existed alongside the other state armies ( Saxon Army , Bavarian Army , Württemberg Army ).

In accordance with Article 63, Paragraph 1 of the Imperial Constitution of April 16, 1871, during wartime there was an all-German army under the command of the Emperor. In times of peace, on the other hand, the federal princes with their own army (Prussia, Saxony , Württemberg and Bavaria ) had the right to command. Thus, in times of peace, the Prussian king (who was also German emperor) had supreme command of the Prussian army. In addition, the Prussian parliament retained the right to the military budget in times of peace . With the founding of the empire, no federal state had any sovereign right to wage war.

The Prussian army as a legally independent army was disbanded in 1919 with the establishment of the Reichswehr after the first World War was lost .

An important reference work for and about the Prussian army was - and still is today for historians or genealogists , for example - the ranking list regularly published by the War Ministry in Berlin .

| year | 1646 | 1656 | 1660 | 1688 | 1713 | 1719 | 1729 | 1740 | 1756 | 1786 | 1806 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| soldiers | 14,000 | 25,000 | 8,000 | 30,000 | 38,000 | 54,000 | 70,000 | 83,000 | 150,000 | 193,000 | 240,000 |

| year | 1807 | 1813 | 1815 | 1825 | 1840 | 1859 | 1861 | 1867 | 1870 | 1875 | 1888 |

| soldiers | 63,000 | 300,000 | 358,000 | 130,000 | 135,000 | 150,000 | 211,000 | 264,000 | 313,000 | 325,000 | 377,000 |

After the dissolution

Article 160 of the Versailles Treaty limited the size of the (not only Prussian) land army in the German Reich to 100,000 and that of the navy to 15,000 professional soldiers . The maintenance of air forces , tanks , heavy artillery, submarines and capital ships was prohibited to the Reich. At the same time, the general staff , military academies and military schools were disbanded .

Most of the soldiers were released; many found it difficult to find their way into civilian life after the war.

Reichswehr Minister Otto Gessler contented himself with limited political and administrative tasks during his term of office; the chief of army command, Hans von Seeckt , succeeded in largely removing the Reichswehr from the control of the Reichstag. Under Seeckt, the Reichswehr developed into a state within a state . It felt more committed to an abstract idea of the state than to the constitution, and it was extremely distrustful of the political left.

V. Seeckt joined the Prussian army in 1885 and had a steep career up to 1918. During the Kapp Putsch in 1920, Seeckt refused to use the Reichswehr against the coup volunteer corps ; but he had the uprising of the Red Ruhr Army brutally suppressed. The Reichswehr also organized the so-called Black Reichswehr, a secret personnel reserve networked with paramilitary formations, of which it saw itself as the leading cadre. In 1926 v. Seeckt fell.

During the Reich Presidency of Hindenburg , the Reichswehr leadership gained increasing political influence and ultimately also determined the composition of the Reich governments. In this way, the Reichswehr contributed significantly to the development of an authoritarian presidential system during the final phase of the Weimar Republic.

Uniforms and military customs

General

Uniforms in the modern sense were only introduced with the introduction of the standing armies and the establishment of textile manufacturers . The basic color of the uniforms in Prussia was blue. This was cheap to produce and mostly the color of the resource-poor Protestant states in northeastern Europe, such as Sweden or Hessen-Kassel . In contrast, rich Roman Catholic states generally wore light (white, gray and yellow), and rich Protestant states generally wore red uniform skirts (Kurhannover, Denmark, Great Britain).

Originally the uniform was called livery or mount in Brandenburg-Prussia, it was only from Friedrich II onwards that the term uniform became established, but the old terms were still used colloquially for a long time.

As a rough rule, the Prussian soldier was given a new uniform once a year, with a total of up to five sets. The first set was put on for parade, the second as a dress uniform, the third and fourth set for daily duty and the fifth set, if any, lay in the closet in case of war. Every soldier could - after receiving an exchange set - keep his old uniform for free. Usually this was used to dress the family members. So it came about that, especially in the country, the isolated uniforms were worn by the civilian population for years. Most of the Prussian uniforms were manufactured by the royal warehouse in Berlin, which was founded especially for this purpose in 1713 by royal instructions .

The officer's uniform in particular not only fulfilled a representative function, but was also used by its wearers as a means of distinction within the framework of a specific regimental culture . Even without a rank badge, internal differentiations can be made using details of the uniform (e.g. hat feathers, portepees ).

infantry

Kurbrandenburg / Prussian infantry uniforms (1644–1709)

Blue skirt, open at the front, with a collar, waistcoat, trousers and stockings in regimental colors. Wide loafers with clasps, a large cartridge pouch and a wide, open hat or grenadier cap. The officers differed in better fabrics, cuts and embroidery on the uniform. Spontoon , sword and officer's sash were also symbols of their status .

Old Prussian infantry uniforms (1709–1806)

In 1709 regulations for uniform Prussian uniforms were introduced. All soldiers (men and women, NCOs and officers) basically wore the same blue skirt. The skirts differed in the quality of the fabrics and the cuts. In addition a white or yellow vest and trousers of the same color. The gaiters were initially white, from 1756 black, with low shoes. Boots were mostly only worn by the staff officers and generals. Sleeves, borders, collars and lapels were made in the regimental colors. The respective regiment could also be recognized by the shape of the cuffs as well as the color and shape of the buttons, borders, bows, braids and embroidery. Headgear was the three-cornered hat, with the grenadiers the grenadier cap.

Officers could be recognized by their portepee , sash and ring collar . The officers differed from each other by the embroidery on the skirt. From 1742 the generals were recognizable by an ostrich feather on the brim of their hats. NCOs could be recognized by a smooth braid on the hat and braids on the cuffs and on the side arm. Since 1741 in the Guard and since 1789 in general, NCOs from Vice Sergeants were also allowed to wear portepee.

Hunters wore a green skirt with a green vest and more olive-colored trousers with black gaiters, and from 1760 boots.

New Prussian infantry uniforms (1806–1871)

As a result of the French Revolution and the subsequent successes of the Napoleonic armies after 1789, the Prussian uniforms also adapted more to the new French style. Until the fall of the old Prussian army in the battle of Jena and Auerstedt , they were largely similar to the uniforms of the time of Frederick II.

In the course of the army reforms after the fall of the old Prussian army in 1806, new uniforms were also introduced. The basic color remained blue. The new skirts were very short in line with the fashion, the trousers pulled up high, sometimes rather gray, very high stand-up collars, skirts and trousers cut very tight. The shako was introduced in a tall and wide form as headgear . Shoulder pieces or epaulettes to differentiate the ranks were introduced from 1808.

The newly formed Landwehr had a simple uniform with a litewka made of blue or black cloth with a colored collar and wide linen trousers. The badges on the collar, lapel projection, cap edge and lid projection were in the colors of the respective province . They wore a large Landwehr cross on their hats .

In 1843 a new helmet, popularly known as the Pickelhaube , was introduced. The bell was initially cut very high. In general, the uniforms of fashion changed according to the middle of the century to lower and softer stand-up collars, longer skirt tails, wider trouser cut and lower helmet with shorter and round visors in several steps. In 1853 the so-called private button on the collar was introduced as a rank badge . In 1866 the final shoulder pieces for the officers came. The tunic was single-breasted with eight buttons. The boots became lower up to the well-known “ Knobelbecher” shape .

Prussian infantry uniforms in the Empire 1871–1919

The uniforms remained largely unchanged until the outbreak of war. After the founding of the empire, the imperial cockade was worn in addition to the state cockade from 1897 . In 1907 the first field-gray uniform was introduced on a trial basis , but it was only to be worn in the event of war. The field gray uniform underwent some changes up to the beginning of the war and during the war, for example the color was more gray-green, but the name field gray was retained. During the World War , only a field-gray uniform was worn, initially the spiked hood with a cover, from the middle of the war the M1916 steel helmet was introduced across the board.

Hunters and riflemen wore a dark green tunic and a shako as headgear. The artillery also wore a dark blue tunic with a black collar. The tip of the helmet ended in a ball. The soldiers of the train wore dark blue tunics with light blue collars and a shako.

cavalry

The hussars wore an Attila in regimental colors with cord trimmings and armpit cords. Some regiments also wore fur. The dragoons had a tunic made of cornflower blue cloth with collars, lapels and epaulettes of different colors depending on the regiment. The helmet was similar to that of the infantry. The Uhlans had an ulanka (tunic) made of dark blue cloth with epaulettes and, depending on the regiment, different colored collars, lapels and lugs. A chapka was worn as headgear . The cuirassiers had Koller white Kirsey with matching collar and epaulets, according to regiment with different colored cuffs, trimmings, advances and collar Patten. Headgear was a steel helmet (cuirassier helmet). The hunters on horseback had a rollerball and tunic made of gray-green cloth with light green epaulettes and lapels. Blackened steel helmet as headgear.

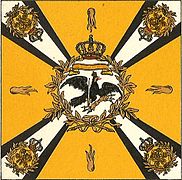

Troop flags

- Troop flags of the Prussian army

Troop flags as a recognition and identification symbol of military units had a permanent place in the Prussian army. In 1713 King Friedrich Wilhelm I laid down uniform dimensions and motifs for the flags and standards of his troops. The flags were square, the standards a little longer than wide and had a triangular cutout on the side facing away from the stick. Both had the Prussian eagle in their midst in a laurel wreath with a crown . In the corners were the seals of the respective rulers, also in a laurel wreath with a crown. In addition, different colors were specified for the basic cloths for the individual branches of the army. The edge was bordered with gold-colored borders.

Ranks

Rank groups

There were six rank groups in the Prussian army: 1st men (common), 2nd non-commissioned officers (with and without porters ), 3rd subaltern officers , 4th captains , 5th staff officers and 6th generals .

The team rank was limited to the simple soldier , called "commoner" at the time, who was also designated according to the respective branch of service and, as a second rank, the private in the infantry. With the cavalry one completely renounced the level of private service. It was not until 1859 that this changed in part with the introduction of the corporal rank. However, this rank was limited to the artillery. In the course of the 18th century, some rank designations in Prussia were modernized. Instead of the previous names Obristwachtmeister and Obrist, the names Major and Colonel prevailed.

In the 18th century, rank badges to differentiate between the various ranks were not yet common. They were only introduced in Prussia in 1808. With the introduction of uniform uniforms in the Prussian army, the officers gradually received badges to differentiate between the various classes of rank. Wearing a sword was already considered a badge of rank in the 18th century. Other distinguishing features were, for example, the quality and cut of the uniform itself.

The ranks of the Prussian army were a model for the ranks of the following German armies up to the present day Bundeswehr .

| infantry | cavalry | artillery | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teams | |||

| musketeer

Fusilier grenadier |

equestrian | gunner | No authority, lowest rank. |

| Private | Private | Bombardier | In the 18th century, the private was the first member of a company , each private was the leader of a group (that is, the soldiers who stood in the members directly behind him). The private was the only crew grade in the Prussian army until 1845 and the deputy of the corporal. Bombardiers (until 1859) were an intermediate stage between the gunners and the non-commissioned officers and superiors of the gunners. |

| ( Corporal ) | unavailable | Corporal | In 1845 the rank of corporal was newly introduced. He received the sergeant's award buttons on the collar and the sergeant's tassel on the sidearm. From 1853 onwards, no more corporals were appointed. In the foot artillery, however, there was the corporal up until 1919. |

| NCOs without portepee | |||

| corporal | NCO /

Corporal |

Corporal | The corporal commanded a "corporal team" of up to 30 men. Three per company. Among the hunters, the NCO was called Oberjäger . |

| sergeant | sergeant | Sergeant / Fireworker (foot artillery) | Like the sergeant stood in front of the sergeant of a squad. Reintroduced in 1843 after having been abolished in the meantime and partly used synonymously with the term " Sergeant ". |

| NCOs with portepee (from 1741 initially in parts of the Guard, from 1789 generally) | |||

| Vice Sergeant or Vice Sergeant | Deputy sergeant | Vice sergeant (foot artillery) / vice-sergeant or vice-sergeant (mounted art.) | The rank was introduced in 1846 in the Prussian Landwehr and in replacement formations, in 1873 in the entire army. In companies with no more than two officers, vice sergeants (in mounted troops: vice sergeants) acted as platoon leaders - a position generally assigned to a lieutenant or first lieutenant. |

| sergeant | Constable | Chief Fireworker (Foot Art.) / Sergeant (Berit. Art.) | Highest rank of non-commissioned officer. The sergeant was entrusted with internal and administrative duties and worked closely with the company commander. |

| Officer deputy | Officer deputy | Officer deputy | The service position was created in 1887. Active Vice Sergeants and Sergeants after at least four years of faultless leadership could be promoted. Two posts per company were set up during the First World War. |

| Subaltern officers | |||

| Ensign |

Cornet /

Ensign |

Junker | Lowest officer rank until 1807, then officer candidate in the rank of non-commissioned officer. Carried the regimental flag. (also free corporal ) |

| Sergeant Lieutenant or Sergeant Lieutenant | Sergeant Lieutenant or Sergeant Lieutenant | Sergeant Lieutenant or Sergeant Lieutenant | Since 1877 lowest officer rank, also in mounted troops (there not a sergeant lieutenant). Top rank of the NCO career, not to be passed through by candidate officers. The rank of lieutenant, but no officer license ; therefore always ranked behind the holder of the "real" rank. Hybrid position between officer (formal affiliation) and non-commissioned officer (social affiliation); Until 1917 excluded from the officers' mess and from the court of honor. |

| Lt. or seconde-Colonel or Sekondelieutenant | Lieutenant etc. | Fireworks lieutenant (Fußart .; not: F.-Seconde-Lt.) / Leutnant etc. (Berit. Art.) | Deputy of the captain, control of the practical service and the NCOs. |

| First lieutenant or first lieutenant or premier lieutenant | First lieutenant etc. | Fireworks premier lieutenant or fireworks lieutenant / first lieutenant etc. (Berit. Art.) | Deputy of the captain, control of the practical service and the NCOs. |

| Captains and captains | |||

| Capitaine / captain / staff captain | Rittmeister / with dragoons up to the 18th century: captain or captain | Fireworks Captain (Fußart.) / Rittmeister (Berit. Art.) | In the 17th and 18th centuries the title “captain” replaced the “captain” for a long time. He was reintroduced into the Prussian army by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. (1842) |

| Staff officers | |||

| Oberstwachtmeister / Major | Constable /

major |

Fireworks master (head of the Oberfeuerwerkerschule in Berlin) / major | Provided for the provisions and guard duty of a regiment, mostly commanding a battalion. |

| Lieutenant Colonel or Lieutenant Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel etc. | Lieutenant Colonel etc. | Representative of the regimental commander |

| Colonel / Colonel | Colonel /

Colonel |

Colonel /

Colonel |

Commander of a regiment |

| Generals | |||

| Major general | Major general | Major general | Leader of an association consisting of 3–6 tactical units |

| Lieutenant General or Lieutenant General | Lieutenant General etc. | Lieutenant General etc. | Commander of a wing, entitled to be addressed as " Excellence " |

| General of the Infantry | General of the cavalry | General of the artillery | Meeting Commander (part of an army in battle formation, usually two meetings in one battle) |

| Colonel General | Colonel General | Colonel General | Since 1854, Colonel General was the designation of the highest regularly achievable rank of general in the Prussian army. |

| Field Marshal General | Field Marshal General | Field Marshal General | Title for special merit, for example a battle won, a stormed fortress or a successful campaign. |

Rank badge

(from 1866)

The private wore an award button (the so-called private button) with the Prussian eagle on each side of the collar. The corporal corporal wore the larger badge of the sergeants and sergeants on each side of their collar , as well as the saber tassels of the NCOs.

NCOs without portepee wore gold or silver braids on the collar and the lapels of the tunic. Saber tassel or thong with a tassel mixed in the national color. The sergeants wore a large award button.

NCOs with portepee ( sergeant , sergeant , deputy sergeant and deputy sergeant ) carried the officer's side rifle with portepee.

Deputy officers wore the badges of the vice sergeants (or vice sergeants) with the officers' buckle belts. The epaulettes had a braid edging.

Lieutenants and captains wore a shoulder piece (armpit) made of several strings lying next to each other. On it were the numbers or names stamped from metal, which the teams also wear. A simple lieutenant wore no star, a first lieutenant wore a silver star, and a captain had two silver stars. The epaulets were without fringes, otherwise like the shoulder boards.

The staff officers' epaulettes had braided cords with silver running through them. At the major without a star, the lieutenant colonel had one gold star, a colonel two gold stars. On it were the numbers or names stamped from metal, which the teams also wore. Epaulets with silver fringes, otherwise like the shoulder boards.

The generals had oak leaf embroidery on the collar and lapels. On the shoulder pieces the golden braided cords were interwoven with silver. Major general without a star, lieutenant general one star, infantry general, etc. two stars, colonel general three stars and field marshal general two crossed command posts. Golden fringed epaulets.

Armament

- Arms of the Prussian Army

Prussian weapons around 1760 in the Vienna Army History Museum . In the foreground, non-commissioned officers (short rifles).

Showcase in the Spandau Citadel (from top to bottom): Musket 1770, Dreyse needle rifle 1854 and infantry rifle 1871

6 pounder field cannon C / 61 , built from 1860

The armament of the soldiers of the Prussian army differed according to rank and regiment. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the defense material consisted of rapiers , sabers , pikes , bayonets , muskets , rifles (flintlock shotguns), carbines , cannons , howitzers and mortars .

- Epee: In the army, every infantryman wielded a thrusting epee until 1715. From 1732 there was a uniform model for the cuirassiers, from 1735 also for dragoons.

- Saber: The hussars built in 1721 received a saber based on the Hungarian model from the Potsdam rifle factory.

- Pike: NCOs of the Prussian army first wore halberds , then a 2.35 m long partisan-like short rifle , which was replaced after 1740 by a three-meter long short rifle in the regiments intended for the first meeting of the order of battle. After the Seven Years' War these were replaced by bayonet rifles

- Bayonet: Bayonets were added as new edged weapons from the end of the 17th century . Actually part of the fire rifle, their appearance, in addition to the technical improvement of the firearms, was decisive for the sorting out of the pikes.

Firearms have been the main weapon in combat since the 17th century. Before 1700 were flintlock rifles introduced, the Luntenschlossgewehre peeled off. A new pattern was introduced under Friedrich Wilhelm I when rifles were bought from Liège from 1713. Based on the same model, rifles called Infantry Rifle Model 1723 were built in the Potsdam rifle factory from 1723 onwards. This was mainly used for the own army. The pattern from 1740 remained authoritative for the time of the Seven Years' War and afterwards. It was not until 1780 and 1787 that new models were added to the armament as the M1740 / 1789 infantry rifle . After the presentation of a new infantry rifle by Hauptmann von Nothardt , this new Nothardt rifle M1801 was to be produced and delivered to the infantry, including the fusiliers, with the cabinet order of February 14, 1801 . Until the outbreak of war in 1806, however, only about 45,000 copies of this model were produced, which only covered about 30% of the total requirements for the entire infantry. A major shortcoming of the campaign of 1806, however, was the quality of the rifles in use by the infantry. In some cases, infantry rifles from the Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1795 were still in use, and many rifle barrels were thinned out by frequent cleaning and polishing. Before the outbreak of the war, many reports spoke of inadequate material. In 1811 the infantry rifle M / 1809 was introduced.

In 1740 the field artillery consisted of four cannon calibers (24, 12, 6 and 3 pounders ), an 18 pound howitzer and another 50 and 75 pound mortars; from 1742 a 10 pound howitzer was introduced.

The cutting and stabbing weapons changed little in the course of the 19th century. In the cavalry, every man had a set of firearms consisting of the main weapon, the carbine and a pair of pistols. The carbine was lighter than the infantry rifle and also had a smaller caliber.

In the middle of the 19th century, the armament of the infantry consisted almost exclusively of smooth muzzle-loading weapons, albeit with percussion ignition . The function of such locks was very reliable. Around 240,000 units were built by 1853 and issued to the troops from 1848. In the second half of the 19th century, the Prussian army took up technical advances in weapon production rather cautiously and hesitantly. First the so-called needle guns were added, breech - loading rifles, 60,000 of which were manufactured on behalf of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV in 1840. The breech-loader had a significantly higher rate of fire than conventional muzzle-loaders. Five to seven aimed shots per minute were possible. At that time, a high rate of fire was not considered an advantage, but a waste of ammunition and a sign of poor order. Battle victories were sought by closed bayonet attacks rather than by fire superiority. Therefore, those responsible at the time believed that the modern rifled muzzle-loaders from Louis Étienne de Thouvenin and the Minié rifle , with which most armies were equipped, were competitive. Initially kept secret and only delivered to a few units, it was almost out of date by the time the needle gun was generally introduced in 1859. It was only after almost 20 years that most of the Prussian troops were equipped with the needle gun. For the war against Austria it was enough to meet the requirements, the Austrian Lorenz rifle (M1862), a muzzle loader , achieved a rate of fire that was not even half as high as that of the needle gun. But in the war against France four years later, the rifle was hopelessly inferior to the modern, much more far-reaching Chassepot rifle of the French. The introduction of rifled steel guns with rear loading was even more sluggish. Only the complete helplessness of the short-range Prussian guns in the face of Austrian artillery already armed with rifled guns led to the conversion to rifled breech-loaders after 1866.

Organizations and Institutions

Old Prussian Army

Like all armies in the period from 1644 to 1806, the army consisted of the arms of infantry and cavalry . Artillery was added later as an independent branch of service . The Prussian army focused more on the infantry. In the view of the commanders at the time, the two branches of arms cavalry and artillery represented little more than support forces for the infantry. This is expressed, for example, in the very infantry-centered training of artillery or dragoons . As the increase in the numerical size of the army over the course of time suggests, the number of newly established military units rose in parallel. The regiment represented the largest form of organization in the army for all three branches of arms . The strength of course changed in the course of time, so that standardized figures are not possible.

The infantry gradually trained a total of 60 infantry regiments by 1806.

By 1806 the cavalry had formed a number of 35 regiments.

In 1806 the artillery consisted of 4 field artillery regiments, one mounted artillery regiment and 17 garrison artillery companies.

In addition to these three branches of service, there were also smaller groups in the Prussian army. The technical troops (for example miners and engineers), minstrels , the rudimentary medical services and the field preachers should be mentioned .

New Prussian Army

The old Prussian army was completely destroyed in the war of 1806 by Napoleon, many soldiers were taken prisoner. In 1806, the Prussian generals had painfully learned that the previous organizational structure with the regiment as the largest form of organization, strictly separated according to the individual branches of the armed forces, was no longer up to date. With the reorganization of the army from 1807, it was decided to dissolve the old regiments in their existing form and to create a new structure.

The reformers around Scharnhorst then formed mixed troop formations in which the various branches of service (artillery, cavalry, infantry) were integrated. These troop associations should be able to independently solve all problems / tasks that arise in a battle or in a campaign. Thus, in addition to the previous structure, the following major units were created: 1. the army corps , 2. the division , 3. the brigade .

The new structure of the Prussian army was as follows:

- Army Corps,

- Division,

- Brigade,

- Regiment,

- Battalion,

- Company.

- Battalion,

- Regiment,

- Brigade,

- Division,

After the reform and the introduction of general conscription in 1814, the typical juxtaposition of line army and landwehr in the army emerged. In the event of war, each line regiment was assigned a Landwehr regiment, which together formed a brigade. Another important structural change was the establishment of the Prussian War Ministry from December 25, 1808, instead of the military administration previously divided between various authorities.

From 1807 on, the Prussian infantry was divided into line infantry, light infantry / hunters and the Landwehr infantry. The line infantry kept the old names musketeer, fusilier, grenadier, but there were no longer any differences outside of the name range. The cavalry was also divided into a line cavalry and the Landwehr cavalry, but the latter was disbanded in 1866. The line cavalry continued to consist of different types of cavalry: the cuirassiers, hussars, dragoons and, recently, the lancers . A special case in the army were the regiments of the guards, which together formed the guards corps (army corps with their own structure). By 1914, the Prussian army had trained eight cavalry regiments and 11 infantry regiments.

From the end of 1815 to 1859 the structure of the Prussian army remained largely the same. A major change took place in 1861 as a result of the army reform by von Roon, when additional regiments of the line were established at the expense of the Landwehr, which lost its importance considerably. With the formation of the North German Confederation , further contingents of smaller states were integrated into the army. From the founding of the Reich to the outbreak of the First World War , the strength of the Prussian army increased steadily. It formed up to 80% of the Imperial Army .

In 1900 there were 17 Prussian army corps (plus three Bavarian corps with separate numbering, two Saxon and one from Württemberg). As a rule, an army corps had two divisions . The total strength of an army corps was: 1,554 officers, 43,317 men, 16,934 horses, 2,933 vehicles. The divisions usually comprised two infantry brigades with two regiments each, two cavalry regiments with four squadrons and a field artillery brigade with two regiments. An infantry regiment normally consisted of three battalions, each of which consisted of four companies, i.e. twelve companies per regiment.

In addition, an army corps had one or two foot artillery regiments , a hunter battalion , one or two engineer battalions , a train battalion and, in some cases, various other units, such as a telegraph battalion, one or two field engineer companies, one or two medical companies, railway companies, etc. at their disposal as corps troops. In 1900 an infantry regiment had a peacetime strength of 69 officers, six doctors, 1,977 NCOs and men as well as six military officials, for a total of 2,058 men. A cavalry regiment had 760 men and 702 service horses. This strength applied to regiments with a high budget, regiments with a medium or lower budget had a lower strength. An infantry company with a high budget had five officers and 159 non-commissioned officers and men, with a lower budget four officers and 141 non-commissioned officers and men.

In 1914 the Prussian army comprised 166 infantry regiments, 14 hunter / rifle battalions, 9 machine gun detachments, 86 cavalry regiments, 76 artillery regiments, 19 foot artillery regiments (fortress artillery), 28 engineer battalions , 7 railway battalions , 6 telegraph battalions, 1 aircraft battalion, 4 aircraft battalions Departments.

Army constitutions

The army constitution of the 18th century was based at the same time, with varying proportions, on a recruited mercenary army from foreigners and an early conscripted cantonal army based on the Swedish model from natives. All swore an oath of allegiance to the king alone and thus the army was the monarch's sole executive body and his main political means both internally and externally. In addition, the army had no constitutional link in a state that did not yet have a modern-day separation of powers or a codified state constitution .

This army constitution lost its validity with the revolutionary wars. Revolutionary popular armies displaced mercenaries. General conscription made the people more central to the political process.

The Prussian army under the Defense Act of 1814 stood on completely different social pillars than the old Prussian army. The new order lasted until the army's existence came to an end. Boyen's military law of September 3, 1814 was based on an elitist concept of the nation. It tried to reconcile the bourgeoisie with the army and tied in with the military constitution used in the wars of liberation. It represented a codification of central reform ideas. Bourgeois-liberals, less democratic ideals shaped the new system. It was more modern than the stuck state constitution, but the army was reserved for the king alone. Their institutions were not affected by the new thinking. On the one hand, all layers of society were henceforth involved in roughly equal shares in the army; on the other hand, the Frideridzian system had been preserved to some extent, due to the one-sided assignment of command to the king and the separation of the army constitution from the state constitution.

Doctrines, images of war, strategies and tactics

The members of the Prussian army never acted in isolation and detached from external influences, but remained embedded in a pan-European network and, as part of this international association, followed the current changes. Such supra-personal, transorganizational processes were conveyed to military personnel through intellectual teaching concepts at military schools and in action. The current doctrines, hierarchically following images of war, including the following war strategies and finally deployment tactics, were teaching concepts valid throughout Europe for members of the military of all armies of that time, which significantly guided and determined their actions and thinking in active service.

As a result of the influence of external influences on the institution of the Prussian army, it was isomorphically similar to the structures of the other army, albeit with a time lag. The doctrine of the Prussian army, the war images of the generals and their developed war strategies and tactics were ultimately only derived derivatives of higher-level, Europe-wide guidelines that limited the spectrum of permissible action, decision-making and design. In the early modern military system , these requirements began to be increasingly written down and regulated. These organizational rules were always broken when the army fell behind in an international comparison, because new developments in other armies had brought about changes in the organizational system. Before organizational measures such as restructuring or personnel changes could take effect, models and new concepts of warfare had first spread through discourse and exchange and found general acceptance in the army. This active process could in some cases last for decades. Such time periods were relevant in the 1790s or also in the 1840s. They were followed by significant Prussian army reforms, which ultimately led to fundamental structural changes.

The second half of the 18th century was marked by lasting changes in the field of warfare and corresponding changes in the image of war . The military strategy in the age of absolutism was determined by the defensive idea. By anticipatory maneuvering of the army through the leadership, enemy supply lines and magazines should be captured in order to destroy the enemy's base of operations . The concept developed in the revolutionary wars aimed at the general destruction of the enemy armed forces. Movement and contact with the enemy were part of the military commanders' strategy canon. Hans Delbrück called the former strategy the fatigue strategy and the latter the prostrate strategy . In the tactical area, the defensive strategy corresponded to the linear tactics , on the other hand the combat tactics of the French revolutionary armies were determined by the thrust of the relatively independent operating columns of the tirailleur tactics (rifle combat ). The image of war changed from a cabinet war to a people's war . The guerrilla war took shape and led to the creation of autonomous volunteer corps that were detached from the army . B. Kleist (1760), Hirschfeld (1806), Krockow (1807) and Lützow (1813). The Prussian army had considerable problems converting the old defensive system to the more offensive system. This led to the defeat in the battle of Jena and Auerstedt in 1806. It took a catastrophic defeat to align the institution of the Prussian army as a whole with the new military age. This succeeded in an exemplary manner in the second attempt and the army regained its old strength in Europe and was able to maintain this until the end of the army's existence.

By the mid-19th century, the industrial revolution in Western Europe and the United States brought a wealth of new technology to the army command of the time. This changed not only the existing image of war, but also the armies themselves. Just like the technical innovations, the method of mass production was new and revolutionary and made it possible to set up and equip far stronger armies than before. In 1815, a total of 200,000 men from three armies fought against each other near Waterloo. Half a century later at Königgrätz, all the armed forces involved already numbered over 480,000 men. The new technologies affected both the tactical and the operational-strategic level of warfare. The increased range of guns and the higher frequency of fire of the infantry weapons forced the attack columns to move far on the battlefield. The telegraph, in turn, accelerated the transmission of information and also appeared to be a suitable instrument for facilitating mobilizations and troop leadership in war. The expansion of a railway network in particular created the conditions for a radical change in the conduct of the war, which enabled the General Staff to draw up precise deployment plans and to concentrate large numbers of troops punctually and precisely at the borders in a fraction of the time previously required.

General Staff

For the tasks of combat deployment planning and practical leadership in the field, the early modern armies increasingly saw the formation of a staff to lead subordinate units, federations, large associations or other departments of the armed forces. These consisted of specialists and high-ranking officers. Elector Friedrich Wilhelm created the forerunner of the modern general staff , a quartermaster general based on the model of the then highly respected Swedish army. The task of the staff was to supervise the engineering service of the army, to monitor the marching routes and to select camps and fortified positions. At the same time, similar institutions emerged in England under Oliver Cromwell , in the Habsburg Monarchy and other southern German states. Under Frederick II, the general staff officers were functionally better placed adjudants and command recipients of the king than an autonomous advisory body.

Christian von Massenbach and Levin von Geusau developed the facility further in 1803. Under Gerhard von Scharnhorst, the General Staff was then institutionally anchored from 1808 as a central body in the newly established War Ministry with the General Staff officers in the newly formed troop brigades.

The Prussian general staff proved itself in the wars of liberation against France and in the wars of unification. The military planning was based on military science principles.

The greater army strength in the middle of the 19th century necessitated an expansion of the operational areas, especially in order to meet the growing need for food. This in turn made new management tools and structures necessary. In most armies, the general staffs, initially only insignificant auxiliary organs of the military commanders, increasingly took over the management of the operations.

Officer corps

The rulers paid special attention to the officer corps . The soldiers 'king and Friedrich II in particular devoted time and attention to the officers of the army, which went down to the planning of the officers' individual lives. The approach of the kings was to form a spiritual and moral elite of the nation. They took the recruitment for this from the best and most distinguished families in the country, the nobility. This immediately resulted in an aristocratic character in the officer corps, whose attitude promised stability to the army. In the 18th century, recruitment was often carried out with violence and the use of potential threats. The nobility was compulsorily obliged and domesticated by the service of the weapon and accustomed to the demands of the king. The general background here is also an unexplained power struggle between the nobility and the monarchs, which the latter clearly decided. Re-educating the nobility was a difficult business. The later famous descendants of von Bismarck , Alvensleben , and the Schulenburg from the Altmark were at the time in the eyes of the kings after Gustav Schmoller "recalcitrant troublemakers, moreover uneducated, raw and lazy".

Army Administration

Of great importance for the transition to miles perpetuus was an efficient army administration which first had to organize the financial payments and human resources. The troops eventually had to be supplied and armed. The process of transition to the standing army, in addition to stabilizing the troops, resulted in greater nationalization. The administration of the troops was carried out autonomously through its own regimental structure until 1655. The regimental colonel was the actual administrator, the regiment owner and commercial director. Only with the creation of institutions such as the war chancellery and the generals were organs created that were supposed to guarantee the strict control according to the specifications of the sovereign. War commissioners controlled the officers, arranged the accommodation and meals for the troops, and collected taxes, which they also administered. Grain magazines and arsenals were built on other structures , the administration of which was also subordinate to the war commissioners. In addition, a steadily increasing property portfolio belonged to the army, which also had to be managed. In addition to the fortifications of the garrisons, functional facilities such as bakeries, forage sheds, train sheds , assembly depots, barracks , guard houses , horse stables and powder magazines were also part of the army. The army administration of the old Prussian army was part of the state administration until the beginning of the military reforms at the beginning of the 19th century . The army and army administration were thus institutionally separated.

Cadet institutions

The Prussian cadet schools served as an educational institution for the children of impoverished noble families . The offspring were given a proper training and education and at the same time the army was able to cover part, according to Gerhard Ritter around 1850, "a good half" of the recruiting needs for the officer corps.

Elector Friedrich Wilhelm founded the so-called cadet corps with the institutions in Kolberg , Berlin and Magdeburg . The Kolberg Cadet Corps consisted of 60 to 70 cadets and was transferred to the newly formed "Royal Prussian Cadet Corps" in Berlin in 1716, where it was increased to 110 cadets. For this corps there was a separate cadet house in Berlin from 1717 . In 1719 the cadets were also transferred from Magdeburg to Berlin, and the Berlin cadet corps now consisted of 150 cadets. In 1776 the Berlin Cadet House was rebuilt . In 1790 it consisted of 252 cadets.

Further cadet schools were founded in Stolp (1769), Kulm (1776) and Kalisch (1793). The cadet institute in Stolp founded by Friedrich II was initially designed for 48 cadets and was expanded in 1778 to up to 96 cadets, who were taught in six classes. The cadet house in Kulm was initially designed for 60 cadets and was expanded to 100 cadets in 1787 with a permit from King Friedrich Wilhelm II. In 1793 there were 260 cadets in Berlin, 40 cadets in Potsdam, 96 cadets in Stolp and 100 cadets each in Kulm and Kalisch. In the Peace of Tilsiter Kulm and Kalisch were ceded, Stolp was dissolved in 1811 and moved to Potsdam. After the end of the Wars of Liberation , Kulm was rebuilt before the institution was moved to Köslin in 1890 .

In 1902 the Prussian Cadet Corps consisted of eight cadet houses and the main cadet institute .

Living conditions of members of the army in the old Prussian army (1644–1807)

Housing conditions

After the introduction of the standing army by the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm, the life of the soldiers changed fundamentally. At the time of the Thirty Years' War , the mercenaries were entitled to pay and the booty when they stormed and sacked a conquered city. There was no other entitlement to food. There was also no uniform legal and punishment system for the soldiers. In summer the troops remained in temporary camps and in winter they were billeted.

This form of billeting now became common for the standing regiments. This means that the citizens had to provide the soldiers with a room (facing the street) in their houses. This billeting caused a considerable burden on the landlords (this is especially true for married soldiers). In return, the landlords received 14 groschen per month for a married soldier and 10 groschen per month for an unmarried soldier. The cavalry regiments were initially in rural villages, but were then moved to the cities. The reason for the relocation lay in the better control of the soldiers in the city (the city as a closed system) and the excessive lack of discipline of the same against the rural population. All homeowners not affected by billeting had to pay a tax.

The unmarried soldiers had to run their household together with other soldiers in a friendly manner . The daily grocery shopping and the preparation of meals was done independently and without paternalism.

Only in the fortress towns of Magdeburg and Kolberg were the teams in barracks in the period before the Seven Years' War. Otherwise it was a long time before the entire army was housed in its own barracks . Shortly after the Seven Years' War, the first cavalry barracks were built in Berlin, and others soon followed. These should primarily take in the married soldiers and their families. The first infantry barracks were built in Prenzlau in 1767. It was intended for 240 men. Further barracks followed in Berlin, Spandau , Nauen , Neuruppin , Frankfurt / O and Königsberg . In these barracks, too, the capacity was 240 men. However, the barracks were nowhere near enough to accommodate all soldiers and their families.

A married man with his wife and children and two unmarried soldiers shared a room in the barracks. The cleaning was the responsibility of the married man's wife. In return, she received 6 groschen a month from each soldier. These cramped living conditions led to frequent conflicts and violent clashes.

Some soldiers were allowed to marry if the ratio to unmarried people in a company did not exceed 1/3. For this they needed the permission of the company commander . The recruited foreigners in particular were welcomed to marry, as the risk of desertion was then considerably reduced.

Earnings and maintenance

A simple foot soldier received one thaler and eight groschen a month after deducting bread and clothing costs (for comparison: a meal with drink cost around 2 groschen around 1750, one taler consisted of 24 groschen). The soldiers' quarters, on the other hand, were free and one soldier received 1½ pounds of bread daily. Also due to this extremely meager pay, the soldiers were allowed to pursue a profession in order to receive additional income. There were master craftsmen, the unskilled worked for the cloth makers, as wool spinners or as henchmen in the building trade. During a campaign, the soldier took care of himself from his salary and the allowances he received. These were two pounds of bread a day and two pounds of meat a week.

As for the officer rank, an officer of the lower ranks had to be satisfied with a very low salary of 9-13 thalers per month. From this he had to finance the lavish, professional life that was expected of an officer. Thus, such a position was a losing proposition for a long time. Only with the rank of captain (commander of a company), which one achieved after an average of 15 years of service, could the officer expect a more abundant income. In addition to the military command, the commanding officer of a company was responsible for the financial management of a company. If the captain of a company managed well, he could generate a surplus of 2000 thalers per year, which he could claim for himself. The actual pay, however, was still tight and was around 30 thalers per month.

Recruitment and desertion

At the beginning of the early modern period, three recruiting procedures were common among the infantry: recruiting volunteers, compulsory drafting, and recruiting from mercenary entrepreneurs. The latter method was the most common, especially during the Thirty Years War. For a sum of money, the mercenary entrepreneurs put together a ready-made army for the princes. The rulers were often dependent on these entrepreneurs and at the same time on unreliable multinational mercenary troops.

A change in the way soldiers were recruited in Prussia occurred when the mercenary army passed to the standing army at the end of the 17th century. The goal was to create a standing army of professional soldiers who would serve even during peacetime. As a result of the War of the Spanish Succession, the army was no longer able to replace the high losses in the regiments with free advertising , so the main concern of the Prussian army was no longer the financing system, but the problem of raising funds. Thus, compulsory advertising was used as the main recruiting system over. In practice, the recruits were drawn from now on with the help of residents' lists. Despite the resulting problems ( desertion ), the process of pressing parts of the population into soldiers prevailed. In the course of the War of the Spanish Succession there was real manhunt. The advertisers used all sorts of lists and crimes in order to get hold of the tallest men possible. The War of the Spanish Succession, for example, radically changed the type of soldier within the Prussian army, from voluntarily hired mercenaries to pressed, compulsory soldiers. Instead of a life profession, being a soldier had degenerated into a lifelong fate with no way out.

After the war and the return of the regiments to the garrison , a wave of desertions set in that exceeded anything that had existed before. In 1714 alone 3,471 musketeers (almost three complete regiments ) deserted . The resulting shortage of soldiers provoked another manhunt, in which the recruiters brutally, ruthlessly and arbitrarily recruited every man they could get their hands on. This led to civil unrest in some of the country's provinces. Many young men left the country during this period for fear of lifelong military service.

A major desertion conspiracy occurred in Potsdam in January 1730, when 40 Guards Grenadiers of the particularly familiar Royal Regiment No. 6 ( tall fellows ) agreed to leave the garrison, murdering and plundering. The planned revolt, which in essence probably originated from grassroots sectarians, was exposed before it was carried out. The main ringleaders were punished in a manner typical of the time. Those involved were questioned, sentenced under martial law and publicly punished. One of the three grenadiers who were believed to be the main ringleaders was injured with red-hot pincers. Then they chopped off his oath fingers and hung him. The second also had to go through the forceps torture before his nose and ears were cut off and then brought half dead to the Spandau fortress prison, where he died. The third was slapped and whipped by the executioner and then taken into custody. The rest of them had to run the gauntlet before they came to Spandau for a certain period of time. A few months later, the royal family also recorded a desertion event. In August 1730, the Crown Prince and his companion Hans Hermann von Katte tried to escape, which has become famous .

The army's susceptibility to desertions only changed with the introduction of the canton system in 1733. This system made the quasi-existing conscription more predictable. The canton system also contributed to keeping desertions within limits. A total of 30,216 Prussian soldiers deserted from 1713 to 1740. In 1720 820 infantrymen deserted, in 1725 only 400 infantrymen. This number remained roughly constant until 1740.

During the Seven Years' War the desertion rate of the Prussian army was no higher than that of other European armies. In addition to the figures, good evidence is the refusal of the vast majority of the prisoners of war to join the Austrian army. This despite the fact that they could not hope to return and the detention conditions were very poor. Even in the bitterest moments, for example after the battle of Kunersdorf in 1759, the Prussian army lost only a few men to desertion compared to other European armed forces. The non-Prussians in the Prussian service had no higher desertion rate than the Prussians themselves.

Military training and everyday life

| Service offense | Sanction |

|---|---|

| after the 10th appearance for roll call in a drunk state | Running the gauntlet by 200 men |

| unauthorized removal from the guard | 10 × gauntlet run by 200 men |

| Sleep on the guard | 10 × gauntlet run by 200 men |

| contradict a supervisor | Run the gantlet |

| physical attack against superiors | Death by shooting |

| Desertion | 1st and 2nd time running the gauntlet, 3rd time death by hanging |

| prohibited gambling | Run the gantlet |

| Fighting among soldiers | Run the gantlet |

| Offense against intoxication | Doubling of the basic offense penalty |

| Careless control of the horses by NCOs | 4 days crooked closure |

| Misappropriation of horse feed | 12 × running the gauntlet by 200 men |

| incorrect report by NCOs | 4 days crooked closure |

| Self-mutilation | 2-3 year old cart , then expulsion from the country |

| attempted suicide | Cart, up to a lifetime |

| Riot | death penalty |

For the line tactics of the time in combat, soldiers were required who had perfect command of their weapon and lockstep and who functioned reliably even under the enormous stress of the battle. The result was a system in which the soldier was trained to be a willless enforcer of the orders of his superiors.

Everyday military life during the year and a half of training or the annual two-month period of service consisted of up to five hours of drill and drill exercises on parade grounds and subsequent cleaning and cleaning of the equipment. Work started at 5:30 a.m., but work usually closed around noon. For the drill and drill exercises , corporal punishment was also used (until 1812), although this was legally limited. According to the catalog of military punishments, anyone who beat a man bloody while being beaten was punished.