Imperial maneuvers (German Empire)

As Kaisermanöver of was during the time of the German Empire , the most important and most extensive military maneuvers referred to, which takes place annually in the presence held the emperor. Such large-scale exercises were also common in other European countries at the time, such as the Russian Empire , the Kingdom of Italy or Switzerland .

Components of an imperial maneuver were the imperial parades of the participating army corps , the naval parade, the naval maneuver and the army maneuver lasting several days. Fleet parades and maneuvers were mostly omitted if none of the participating corps had access to the sea. The participating land forces were mostly formed by two of the largest military groups, the army corps of the German Army . For contemporaries at home and abroad, these maneuvers represented a basis for assessing the combat value of the German army. In the same way, they were supposed to clarify the questions about military training that are still relevant today, as they also provide information for political historiography.

history

Although the major exercises for tactical advanced training had a weight that should not be underestimated because of their stabilizing effect on domestic politics, the imperial maneuvers in the pre-war years were the preferred subject of public criticism due to their high-profile function.

A certain monotony had arisen by the time Wilhelm II came to power, when the V and VI, the VII and the VIII Army Corps maneuvered against each other at regular intervals. The corps hardly got out of their own province like this. Nevertheless, not only the spectators, but also the participating soldiers felt the pathos that emanated from the mechanism of the armed forces.

Then the X. maneuvered against the VII. Corps, the VIII. And XI. against two Bavarian army corps (1897), or in 1903 two Prussian against two Saxon corps.

External impact

The 1890s

Foreign criticism saw the maneuvers of that time as pompous maneuvers . They neglected the requirement of military exercises and, above all, had to satisfy the emperor's war games .

Tactically nonsensical images of the year 1897 found their counterpart in the dense rifle developments of 1898, where, regardless of the enemy weapon development, elbow to elbow was charged. In 1899 a massive army corps was set up against a village, with Wilhelm II leading a cavalry corps against the flank of the enemy line-up.

The French observers saw this as the culmination of what they saw as a long outdated tactic of mass advance.

The new century

The limited tactical evolution was noted in 1900. The push tactics were weakened with the retreat of the column formations, but the dense shooting lines still dominated. Approaches to interaction between infantry and artillery were registered for the first time. However, this was not a turning point in German tactics because any hint of a shift away from mass foray past days by an attack of the Emperor at the head of 59 squadrons was nullified cavalry on September 12 1900's.

This development intensified until 1904. Although the increasing military spirit and attention to technical developments indicated the ability to learn processes, tactical thinking in practice did not get beyond the stereotypical repetition of the encirclement.

The Boer War and the Russo-Japanese War caused tendencies to clear out German regulations. However, from the point of view of French critics, no progress was made in terms of flexibility and adaptation to the battle and the terrain until 1906.

At the end of the decade, the German army found itself in a phase of tactical stagnation , which was recognized by foreign countries at the latest in 1910 . The British military correspondent Howard Hensman dealt with the development of the French and German armies. After the imperial maneuver in 1908, he made the unchanged adherence to the teachings of Roons and Moltke responsible for the falling behind the French army . With them one had achieved the victory in the Franco-German War .

The difference between the German and French military doctrine was irreconcilable. The attempt to adopt French methods failed because of the narrow limits of theoretical development. While artillery and cavalry sought a modern form, the infantry remained arrested in traditional forms and methods.

The imperial maneuver in 1911 - the turning point

The military correspondent for the London Times , Colonel Charles à Court Repington , lashed out after the imperial maneuver in 1911. He described the German infantryman as machine-made, slow and lacking interest in his work . While Europe was advancing, the German army was out of date and stood still. Nonetheless, he praised the German doctrine, although he accused it of a difference between the theoretical postulate and practice in the imperial maneuver. It lacks individuality and freshness. His harsh criticism deeply hurt German self-esteem.

From the 1912 maneuver, a change should be noted. The infantry fought more smoothly, the cavalry recently, without losing sight of the attack, on foot, and the artillery adopted French methods in battle. The basic concepts of fire and movement remained hidden from them. An outdated and antiquated volley and mass fire still determined the fire activity. The lack of combat intelligence by the Germans was felt to be serious. It was an offensive urge without explanation.

Preparation for war

The advances in the branches of service remained limited. In maneuvers, the cavalry had developed into an army vanguard, according to French theories. They now fought in close connection with the infantry, which, however, also exhausted the evolution of German operational-tactical thinking. Their further development was limited to modifications due to the offensive à outrance doctrine . Fire control, a central training topic, did not meet the requirements.

In the autumn of 1913 the imperial maneuver did not show a fundamentally different picture from the point of view of foreign criticism. The troop practice appeared decidely dull, although owing to no fault of there own. No initiative was left to the leaders of the corps. The English General Callwell , who was sent as an observer to the imperial maneuver in Silesia on behalf of the Morning Post in 1913 , characterized the German tactics as one-sidedly determined by the offensive. Images had emerged that reduced any belief in a German evolution of tactics since 1900 to absurdity. In response to his articles in the Morning Post , he learned that the General Staff had been satisfied with his criticism. In contrast to Repington's articles two years earlier, his articles gave no reason to repeat the ban on English reporters on the imperial maneuvers of 1912.

When on September 13, 1913 the imperial maneuver with the signal: The whole thing stop! However, nobody suspected that almost exactly a year later the invincibility nimbus of the German army would be gone on the Marne .

Internal effect

The criticism from abroad had its counterparts in the German public as well as in the defense administration, the staffs and the troops. Which were discussed several times among the experts of the Prussian War Ministry and the Great General Staff in the analyzes of the staff units concerned with them.

The anachronism of German tactics in 1895 found expression during the imperial maneuver. Closed detachments were presented to trigger and announce the storm on the enemy positions. The beating of the drum and the signals “open side gun” or “fast forward” should be suitable for triggering the assault of entire battalions in modern combat. Even at the beginning of the First World War , regiments still attacked with the beating of the drum. Although the opposite result had been reached in 1902 after the Boer War, at least one battalion was held on with sounding game. The firmly established traditions of the traditional attack tactics had to be adhered to.

In 1903 in the Reichstag, the Social Democratic MP Bebel highlighted that the emperor was not innocent in the theatrical images of the imperial maneuvers . Above all, the mass deployment of the cavalry was criticized: Where does it actually happen that z. B. the union of the highest commanding officer on the one hand as leader of an army corps and on the other hand at the same time as a critic?

The cavalry was outdated at the latest with the invention of the rapid-fire rifle, but in 1913 cavalry regiments played an essential role in the approval of the large army draft.

The reason for the unhindered self-portrayal of Wilhelm II at the head of the cavalry masses was the limited influence of Chief of Staff Schlieffen on the Kaiser. His weak position formed a weighty reason for the decline of the imperial maneuvers to mere displays. At the beginning of 1904, Wilhelm II expressed his disdain for the staff by wishing to induce Schlieffen to leave his position peacefully in the course of the spring.

That the imperial maneuvers did not form a model for the war-like representation of the battle situation, provided the final picture of the imperial maneuver from the year 1902. The already mentioned mass attacks of the cavalry under the direction of the emperor prompted Count Vitzthum to the conclusion: Unfortunately, the large, theatrical cavalry attacks are after all has become a major requirement of imperial maneuvers in recent years!

The discomfort with the existing conditions reached its peak in September 1904. The emperor's interventions in the layout and implementation of the imperial maneuver were decisive. In the course of the maneuver he had a corps command for the IX. AK wrote himself and so intervened over the head of the chief of staff and the commanding general ( Friedrich von Bock and Polach ), sat at the head of the guard regiment and led it to the attack with unfurled flags.

That process was so precarious that the head of the military cabinet , Count Huelsen-Haeseler , told the military plenipotentiary that he was glad "that the foreign army officers came so late and luckily hadn't seen all of this".

This development came to an end with Schlieffen's dismissal in early 1906. The new Chief of Staff Moltke , who once pointed out the advantages of the Boer tactics over the traditional ones, opposed such phenomena from the start and demanded strict restraint from the emperor during the imperial maneuvers.

For areas where imperial maneuvers took place, they were often economically profitable business for local traders and restaurateurs. The cities' infrastructure also benefited, for example through the renewal of public facilities such as train stations or the renovation of city buildings.

Course of the imperial maneuver from 1904

Imperial parade IX. AK

On the evening of September 3rd, the court train with the imperial couple, coming from the wildlife park station near Potsdam , arrived at Altona main station at around 6:30 a.m. After the reception by the heads of the military and civil authorities, the imperial couple was escorted to the Hohenzollern in the Heuhafen .

On the evening of September 4th, a table was held in the imperial court for the province in the presence of their majesties. Among the guests was u. a. the President of the Province of Schleswig-Holstein , Kurt von Wilmowsky , who in his speech pointed out to the Empress that she was now on home soil. In his counter-speech, the Emperor thanked him and also announced the Crown Prince's engagement to Cecilie von Mecklenburg-Schwerin .

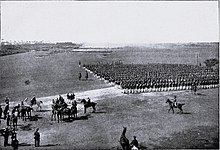

The next day the parade took place. The Kaiser went under the escort of the Königs-Ulanen-Regiment (1st Hannoversches) No. 13 followed by the Empress , under that of the Cuirassier Regiment Queen (Pommersches) No. 2 , over the Flottbeker Chaussee to the parade ground in Lurup .

Already in the morning the flag company, 2nd company of the infantry regiment "Herzog von Holstein" (Holsteinisches) had No. 85 - the emperor gave the regiment its final name on January 27, 1889 and provided the brother of the empress, Duke Ernst Günther zu Schleswig-Holstein , as an expression of the connection to the Prussian army to the outside à la suite of the regiment - picked up the flags consecrated by the emperor in the armory of Berlin on August 28 from the apartment of the commanding general , Friedrich von Bock and Polach . The music corps played the presentation march as a greeting to their arriving Supreme Warlord . At the emperor's signal, the brigade commanders had the rifles presented, whereupon the new flags were handed over to their units.

The procession of the body gendarmerie opened the parade. The Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz presented the 89 regiment , the Empress the 91 regiment and her cuirassiers. The climax of the parade was reached when the Kaiser himself presented his lancers and the Duke of Oldenburg his dragoons . The flags now gathered on Prinz Albrechtstrasse , while the generals , regimental and independent battalion commanders were ordered to criticize. After the end of this period, the emperor took over the march of the flag company on the south side of the town hall . From there over 35 war clubs with their flags and standards lined the way of the imperial couple back to the Hohenzollern .

In the evening, the parade table took place in the ballroom of the Kaiserhof. The highlight of this event, in which the mayors of the three Hanseatic cities represented in the Corps ( Carl Georg Barkhausen , Johann Georg Mönckeberg and Heinrich Klug ) experienced by the emperor that the garsonierten in their cities regiments henceforth the names Regiment Bremen , regiment Hamburg and Regiment Lübeck led .

At 9 a.m. sharp, the big tattoo began on the Kaiserplatz in front of the town hall, which was illuminated on the occasion of the parade . Depending on a company of the 76th (Hamburg) and 31er (Altona) presented the torch bearers under the sounds of Yorck's march to zukommenden from the east of the town hall Musikzug trellis formed. After several marches, a drum roll followed by eight beats ushered in the big tattoo . After the tattoo of the infantry and cavalry, prayer followed. The escort teams presented their rifles to the sound of the national anthem before they left the square in the direction of the train station to the tattoo tune.

After the imperial couple had paid a visit on September 7, the neighboring city of Hamburg, where she headed Albert Ballin the premises of HAPAG visited the Emperor left at night aboard the SMY Hohenzollern Altona.

Fleet parade and maneuvers

After the Kaiser had accepted the fleet parade of the 22 ships in front of Heligoland on the Hohenzollern , he left the Hohenzollern and went to the Kaiser Wilhelm II to attend the maneuver that was to take place off Cuxhaven at the mouth of the Elbe.

At 3 o'clock the next morning the time had come. The battle idea was that the enemy (England) was already in front of Heligoland and was about to attack. However, the maneuver ended faster than expected. A planned landing or involvement of Cuxhaven in the conflict was not carried out. Since the opposing naval formation gained a clear advantage, the emperor issued the order to abort the maneuver.

In the subsequent criticism, the emperor expressed his appreciation for what had been achieved.

The Hohenzollern now drove, followed by the entire fleet, past Cuxhaven into the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal to Kiel .

After the parade dinner there on board the artillery training ship SMS Mars , the Kaiser traveled by special train from Kiel to the maneuvering area in Schwerin . Here he took up residence in Schwerin Castle and the Empress in Wiligrad Castle .

Imperial maneuvers

On the morning of the 12th that stood Guard Corps , reinforced by the Frankfurter Grenadier Guards and at that time the son, Frederick Henry , the Prince Albrecht commanded Dragoons. 2 , in a line of Wismar on Schwerin to Ludwigslust , whereas the IX. , reinforced by the Hussar Regiment No. 3 as well as the 37th Infantry Brigade and the 19th Field Artillery Brigade of the 19th Division of the XAK , was in a line from Grevesmühlen via Gadebusch to Wittenburg .

The reinforcement of the IX. should be loaded onto the ships of the fleet in Travemünde in order to land in the Wohlenberger Wiek during the so-called major battle days of the maneuver and the IX. amplify from there.

From the 14th to the 16th took place between the Guard (red) and IX. Army Corps (blue), the major field maneuvers, in which the Reds were assigned the role of the enemy, took place.

Prince Albrecht acted as head judge.

At 8 o'clock on the morning of the first day the maneuver was interrupted and the emperor took over the command of the guard corps near Goddins . The "fight" developed around Bobitz . Where not far from Bobitz, recognizable by their tethered balloon, the maneuver control under von Schlieffen was. At around 11:15 a.m. the signal was given: Stop the whole thing! the end of the battle in which the IX. AK was “thrown back” behind the Stepenitz .

Since the emperor changed corps the next day, the "fortunes of war" also changed. On the third day the Kaiser was back at the Guard Corps to complete the maneuver, which was now winning again.

A maneuver correspondent for the Lübeckische Advertisements , who was his eyewitness, observed the following: ... Despite this apparently victorious outcome for the left wing of the blue party, the victory was nevertheless awarded to the red party. It must have been the battle on the left wing and in the center of the red party, on which the emperor was found, that tipped the balance.

Places of the imperial parades

Since it can lead to misunderstandings , it should be pointed out that these imperial parades are related to an imperial maneuver. Other uses of the term “Kaiserparade” are possible. In the book "Der Stuhlmannbrunnen" published by the Altona Museum in 2000 on page 14, an image is used that is stored in Wikipedia under the title Altona Kaiserparade . This was held in connection with the opening of the Altona town hall and not an imperial maneuver. That took place that year between the VII and X Army Corps. The IX. Army Corps, which had its headquarters in Altona, was not involved in this.

- 1861: Zieverich (VIII.) And? (VII.)

- 1868: Groß Rogahn

- 1873: Hanover

- 1875: Trier (VIII.) And Bunzelwitz (VI.)

- 1876: Euskirchen (VIII.) And? (VII.)

- 1877: Stockum (VII.)

- 1879: Strasbourg (XV.)

- 1881: Kronsberg

- 1882: Breslau

- 1884: Euskirchen (VIII.) And Wevelinghoven (VII.)

- 1885: Ludwigsburg

- 1889: Minden (VII.) And Kronsberg (X.)

- 1890: Flensburg

- 1893: Eurener (VIII.) And Lauterburg (XIV.)

- 1894: Elbing

- 1895: Szczecin

- 1896: Görlitz

- 1897: between Kärlich and Kettig (VIII.) And between Nieder-Erlenbach and Biebelried (XI.)

- 1898: Minden (VII.) And Kronsberg (X.)

- 1899: Stuttgart and? (XV.)

- 1900: Szczecin

- 1901: Danzig

- 1902: Poznan

- 1903: Zeithain

- 1904: Altona

- 1905: Coblenz (VIII.) And Homburg (XVIII.)

- 1907: Münster (VII.) And Kronsberg (X.)

- 1908: St. Avold (maneuvers) (XV.)

- 1909: Karlsruhe

- 1910: Coblenz (VIII.) And Devauer Platz near Königsberg i. Pr.

- 1911: Altona

- 1914: Another big maneuver in the Rhineland and the imperial parade in Urmitz (VIII.) Were planned for the year. The beginning of the First World War prevented this.

literature

- Bernd F. Schulte: The imperial maneuvers 1893 to 1913. Evolution without a chance. In: Fried Esterbauer (ed.): From the free community to federal Europe. Festschrift for Adolf Gasser on his 80th birthday. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-428-05417-2 , pp. 243-260.

- Bernd F. Schulte: The German Army, 1900–1914. Between persistence and change. Droste, Düsseldorf 1977.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Bernd F. Schulte: The German Army. Between persistence and change. Düsseldorf 1977, p.?

- ↑ Volker R. Berghahn: The Tirpitz Plan. Genesis and decay of a domestic political crisis strategy under Wilhelm II. Düsseldorf 1971, p.

- ↑ Revue de Deux Mondes: Les Tendences Novelles de l'Armée Allmande. 5, Paris 1901, pp. 5-32, Revue Militaire des Armées Étrangères. (Paris) 1898, pp. 43-72.

- ↑ Kriegsarchiv München (KA), Royal Bavarian General Staff (GenStab), Vol. 320, Petit Parisien, Major M. September 15, 1906

- ↑ The United Service Magazine: London, November 1908 issue, article by Howard Hensmen: The French and German Maneuvers. Some points of comparison

- ^ The Times: October 28, 1911 edition, Charles à Court Repington: The German Army

- ↑ Berliner Tageblatt: No. 621, edition of December 6, 1911, Gädecke: The German Army in English lighting

- ↑ So z. B. the hidden firing position

- ↑ R. Kann: Les Maneuvers Impériales Allemandes en 1911 ; Paris / Nancy 1912

- ↑ Le Specteteur Militaire: Vol. 86, 1912, Article: Maneuvres Impériales Allemandes de 1911

- ^ R. de Thomasson: Les Maneuvres Impériales Allemandes en 1912 ; Paris / Nancy 1912

- ^ Charles Edward Callwell: Stray Recollections ; London 1923

- ↑ see e.g. B. here

- ^ Roet de Rouet, Henning: Frankfurt am Main as a Prussian garrison from 1866 to 1914. Frankfurt am Main 2016. S. 161.

- ^ Lübeck advertisements; No. 436, issue of August 29, 1904, section: Latest news and telegrams

- ↑ received z. B. the Altona Infantry Regiment "Graf Bose" (1st Thuringian) No. 31 or the 2nd Battalion of Infantry Regiment No. 162 (formerly III./76) new flags

- ↑ so z. B. that of the 9th Jäger Battalion in Ratzeburg

- ^ (1) Colonel Nazif Bey, Attaché Militaire de Turquie, (2) Le Marquis de Laquniche, Commandant de l'artillerie attaché de militaire à L'Ambassade de France à Berlin, (3) Colonel J. French-Commandant d'Artillerie à Gibraltar, (4) Lieutenant Colonel Frhr. v. Salza- Kgl. Saxon Military Plenipotentiary, (5) WP Biddle -Captain Americain Mitair-Attaché, (6) Lieutenant Colonel v. Dorrer- Kgl. Württ. Military Plenipotentiary, (7) Lieutenant Colonel Kikutaro Oi. K. - Japanese military attaché, (8) SE Smiley-Captain US Army, (9) Colonel v. Schebeko- Aide-de-Camp de SM l'Empereur de Russie, Agent Militaire, (10) Gleichen , Colonel British Militairy Attaché, (11) Le Compte del Peñon de la Vega- Colonel Attaché militaire à l'Ambassade de l'Espagne , (12) First Lieutenant v. Müller b. Guards regiment on foot Berlin, (13) Frhr. v. Loen, Rittmeister in the 18th Dragoon Regiment, Parchim, (14) Le Comte de Gastadello, Militaire-Attache d'Italie, (15) Major Quentin Agnew, Militaire-Attaché d'Angleterre, (16) Alois Klepsch Kloth v. Roden , K. u. K. Oesterr. Ung. Military Attaché, (17) Le Captain Lie, Military Attaché de Suède & Norge

- ↑ Among them Ariadne and Kaiser Wilhelm II , Mars , Swabia , Prince Adalbert , Olga , Carola , Pelikan , Nymphe and Hamburg who had come from Kiel the day before .

- ^ Lübeck advertisements: Edition of September 17, 1904, article: Imperial maneuver 1904. / XXVIII. / (Lüb's own report. Num.) / Experiences of a maneuver contract

- ↑ Since this was the first imperial maneuver in which their regiment , as the Lübeckers affectionately called it, took part, the Lübeck advertisements sent their own correspondent to accompany them. In around 30 articles, he reported in great detail on the maneuver and its events.

- ^ The imperial maneuver in September 1897 took place in the province of Hesse between the two Prussian corps on one side and two Bavarian corps on the other.

- ↑ On the Nauheimer Kopf , where the emperor criticized the maneuver at the end of the maneuver, there is still a memorial stone to this day. On the imperial maneuver in 1905 as well as on the imperial parade and the imperial days in Koblenz 1905 Manfred Böckling: "... that I send you warm greetings from the great imperial parade, this splendid military warlike drama in peace", testimonies of the imperial maneuver and the imperial days in 1905 in and near Koblenz , in: Zeitschrift für Heereskunde, ed. from the German Society for Heereskunde e. V., No. 476 (April / June 2020), pp. 62–68.