Mülheim-Kärlich

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 50 ° 23 ' N , 7 ° 30' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| County : | Mayen-Koblenz | |

| Association municipality : | Weißenthurm | |

| Height : | 76 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 16.34 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 11,215 (Dec 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 686 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 56218 | |

| Primaries : | 02630 (parts of the industrial park: 0261) | |

| License plate : | MYK, MY | |

| Community key : | 07 1 37 216 | |

| LOCODE : | DE MKA | |

| City structure: | 4 districts | |

| Association administration address: | Kärlicher Str. 4 56575 Weißenthurm |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Gerd Harner (FWG) | |

| Location of the city of Mülheim-Kärlich in the Mayen-Koblenz district | ||

Mülheim-Kärlich is a city in northern Rhineland-Palatinate and with around 11,000 inhabitants, the largest municipality in the Weissenthurm association . According to state planning, Mülheim-Kärlich is designated as a sub- center. The place near Koblenz consists of the four districts of Mülheim, Kärlich, Urmitz-Bahnhof and Depot.

location

The city lies on the western edge of the Neuwied Basin between the Rhine , Moselle , Nette and the eastern foothills of the Eifel . Thanks to its convenient location on the A 48 and A 61 federal motorways and the 9 federal highway, the catchment area of your industrial park extends into the Eifel, the Westerwald , the Hunsrück and the Taunus . Mülheim-Kärlich borders the Rhine for around 2 km, although the city center is around 3 km from the river.

history

Prehistory and early history

The area of today's Mülheim-Kärlich is one of the oldest human-settled places in Germany. This is indicated by hand axes made of quartzite and flint , which are around 440,000 years old , artefacts of Homo erectus from Mülheim-Kärlich , which were found in the clay pit on the Kärlicher Berg.

Since the Neolithic Age , from around 4000 BC BC, the region seems to be permanently populated. From about 3700 to 2400 BC BC there was a semicircular earthwork of the Michelsberg culture on the banks of the Rhine, between today's nuclear power plant and the Urmitzer Werth . The complex, protected by ramparts, moats and palisades, enclosed an area of approx. 100 hectares.

Archaeological finds indicate that since the Latène period (from around 450 BC) Celts lived in today's urban area. A Celtic wagon grave was discovered on Weißenthurmer Strasse in 1905 while pumice was being mined . Other burial mounds and an extensive burial ground as well as finds of trade goods, some of which are of Etruscan origin, point - like the place name Kärlich itself - to the existence of a Celtic settlement.

Roman time

Near this settlement, roughly at the point where the Stone Age earthworks had been, took place in 53 BC. BC possibly the second Rhine crossing of Caesar's legions, which he described in “ De bello Gallico ”. After the Roman conquest, the region around Mülheim-Kärlich was initially part of the Germania Superior province (Upper Germany), with the capital Mogontiacum (Mainz). From the time of Diocletian until the collapse of Roman rule in the 5th century, it belonged to the new province of Germania Prima that was formed from it .

The Roman road from Mainz to Cologne crossed the urban area approximately at the height of today's federal road 9. Archaeological finds suggest that a Roman settlement was formed along this road. On the banks of the Rhine, by today's chapel “Am Guten Mann”, there seem to have been factories for the production of bricks and ceramics. The majority of the population at that time were Romanized Celts from the Treveri tribe , Germanic peoples and Romans from all parts of the empire .

Among the archaeological finds from the Roman and post-Roman times, the remains of several Roman include villas and a Germanic runes clip from around 600, the inscription "Wodani hailag" ( "The WODAN holy") but is not considered authentic.

middle Ages

After the collapse of Roman rule, the Ripuarian Franks , whose areas of origin lay east of the Limes , gradually took possession of the land on both sides of the Middle Rhine . At that time, the core of the settlement structures that still exist in the Neuwied Basin emerged. For the period after the year 500, and then increasingly for the 7th century, Frankish individual graves and burial fields in the Mülheim-Kärlicher area have been identified. a. on Heeresstrasse and on the Senser Berg.

The place name Mülheim indicates a foundation during this Frankish conquest in the early Middle Ages , while the name "Kärlich" suggests much earlier, Celtic origins. Nevertheless, both places were first mentioned in a document in the High Middle Ages : Kärlich 1042, Mülheim 1162. At that time they belonged to the imperial estate of the Franconian royal court of Koblenz , which was donated to the Archbishopric of Trier in 1018 by a donation from Emperor Heinrich II . In 1217 the Kärlich church is mentioned for the first time in a document. A hundred years later, the Old Chapel in Mülheim, which is still preserved today, was built , which remained a branch church of the Kärlich parish until the end of the 19th century.

At the beginning of the 14th century, Elector Baldwin of Luxembourg had a moated castle built in Kärlich, which was first mentioned in a document in 1344. Two years later, in 1346, he obtained from his great-nephew, Emperor Karl IV. , The granting of a city privilege for Kärlich. The border security against Kurköln was likely to have been decisive for both measures . For this purpose, however, both the castle and the town of Kärlich lost their importance in the period that followed. Since the beginning of the 15th century, the border was secured by the White Tower , which Elector Werner von Falkenstein had built around 4 km northwest of Kärlich. The electors and archbishops of Trier therefore did not make use of Baldwin's privilege and never officially elevated Kärlich to town and surrounded it with walls. The castle was replaced by a moated castle under Elector Johann II von Baden as early as 1480 , which was no longer primarily used for defense, but for hunting. Kärlich and the neighboring village of Mülheim, which was assigned to his parish, remained Kurtrier rural communities until shortly before the end of the old kingdom and belonged to the mountain maintenance department . Its extension roughly corresponded to the present-day community of Weißenthurm.

Early modern age

In the 17th century both places were badly affected by the Thirty Years' War and the Dutch War of Louis XIV . In 1635, the initially unsuccessful siege of the moated castle by Swedish and French troops, who subsequently plundered the village of Kärlich. In a second attack in July of the same year, the Swedes managed to set the lock on fire. After the Thirty Years' War, between 1654 and 1660, Elector Karl Kaspar von der Leyen had a new hunting and pleasure palace built on the foundation walls of the ruins . As early as 1657, the three clerical electors met there to discuss the upcoming emperor election in Frankfurt . Rebuilt and expanded in the 18th century according to plans by the builders Balthasar Neumann and Johannes Seiz , the Kärlich Castle was a preferred place of residence for the last two Trier princes, Johann IX. Philipp von Walderdorff and Clemens Wenzeslaus of Saxony .

Clemens Wenzeslaus, whose court had become a rallying point for counter-revolutionary forces after the outbreak of the French Revolution , left Kärlich for the first time on October 21, 1792, fleeing from French troops. After his short-term return, the electoral state ended exactly two years later when the Sambre Maas Army under General Marceau , coming from the Netherlands, occupied the left bank of the Rhine near Koblenz. The Kärlich Castle was set on fire by Marceau's soldiers on October 23, 1794 and then used as a quarry by the local population.

After Marceau's troops captured the two places on October 22, 1794, Mülheim and Kärlich remained French until 1814. They belonged to Mairie Bassenheim , the forerunner of today's community of Weißenthurm, which was most recently part of the Rhin-et-Moselle department with its seat in Koblenz. The Congress of Vienna made the Rhineland the Kingdom of Prussia in 1815 . Thus the two municipalities founded in 1816 Prussian arrived district Koblenz in the same administrative region and were until 1945 part of the Prussian 1822 formed the Rhine Province .

Since the 19th century

Until the middle of the 19th century - most recently in 1845 and 1847 - bad harvests repeatedly brought times of need for the population who lived almost exclusively on agriculture. Their economic situation improved noticeably in the second half of the century with the construction of the railway, which opened up new markets for farmers, and with the development of clay mining and the pumice industry. This created additional earning opportunities over the winter months, so that more and more people found their livelihood in the two villages. Emigration was slowed and the population increased rapidly. Another long-term effect was that around 1900 most of the residents were only dependent on their mostly small farms as a part-time source of income. However, the degradation of clay also had fatal consequences at times: Landslide disasters occurred in 1897 and 1906 in which numerous houses in Mülheim were damaged or destroyed.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, the two new districts of Urmitz-Bahnhof and Depot were built. They developed on the edge of the Mülheim district from settlements that had formed around the train station built in 1876 and around an ammunition depot established during the First World War .

During the time of National Socialism there were riots against the Jewish population. In the night of the pogrom from November 9th to 10th, 1938, the Mülheim synagogue on Bassenheimer Strasse was desecrated and burned down. The window panes were thrown in at the prayer house in Kärlicher Burgstrasse. All Jews who had not emigrated were deported between March and July 1942 to the Izbica ghetto established in occupied Poland near Lublin and later to the extermination camps. In World War II , numerous Wehrmacht soldiers from Mülheim Kärlich and died, but both places suffered despite their proximity to the garrison city of Koblenz little war damage.

In the late afternoon of March 8, 1945, units of Combat Command A (CCA) and B (CCB) of the XII. US Corps belong to 4th Armored Division Mülheim, Kärlich and other places between Andernach and Koblenz without a fight. The April 2, 1945 issue of the American “Life” magazine shows on page 22 a photo of a US jeep driving through the white flag-lined Bassenheimer Strasse. In the summer, the US troops evacuated the region which, according to the zone protocol of July 25, 1945, was added to the French zone of occupation . Under French military administration, both villages were initially part of the Rhineland and Hesse-Nassau provinces with their headquarters in Bad Ems .

Since 1946, Mülheim and Kärlich have belonged to the then newly formed state of Rhineland-Palatinate and since the administrative reform of the state in 1969 to the new district of Mayen-Koblenz . The same reform envisaged the unification of the previously independent municipalities. At that time Mülheim had 6903 inhabitants, Kärlich 2663 inhabitants. The municipal councils of both places initially rejected the state government's plan. In a public poll in January 1969, however, just over 50 percent of Mülheim residents voted in favor. The majority of the council also agreed with this vote. In Kärlich, on the other hand, not only the mayor and the municipal council, but also 70 percent of the electorate spoke out against the merger. There was also a dispute about the new, common place name. Ultimately, the state parliament and the interior minister of Rhineland-Palatinate decided that the two villages should be united on June 7, 1969 under the name Mülheim-Kärlich. On June 21, 1996, Mülheim-Kärlich received its town charter .

politics

City council

The city council in Mülheim-Kärlich consists of 28 council members, who were elected in the local elections on May 26, 2019 in a personalized proportional representation, and the honorary city mayor as chairman.

The distribution of seats in the city council:

| choice | SPD | CDU | FDP | FWG | Alliance 90 / The Greens | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 8th | 9 | - | 9 | 2 | 28 seats |

| 2014 | 8th | 13 | - | 7th | - | 28 seats |

| 2009 | 6th | 17th | 1 | 4th | - | 28 seats |

| 2004 | 6th | 17th | - | 5 | - | 28 seats |

- FWG = Free Voting Group Mülheim-Kärlich e. V.

mayor

Mayor of Mülheim-Kärlich is Gerd Harner (FWG). In a runoff election on June 16, 2019, he was elected with 61.02% of the votes, as none of the original three applicants had achieved a sufficient majority in the direct election on May 26, 2019. Harner is the successor to Uli Klöckner (CDU), who held the office for 15 years.

coat of arms

| Blazon : "In silver two diagonally crossed black bishop's staffs, the volutes of which end in an isosceles cross , covered with a continuous red bar cross with an oval silver mill iron in the center of the crossbar." | |

| Foundation of the coat of arms: The Mülheim-Kärlicher coat of arms was created in early 1970 from the combination of the coats of arms of both places. The continuous red bar cross in silver is the cross of Kurtrier , to which both places belonged until the end of the old empire and which both had in their former coats of arms in the same shape and size. The mill iron from the Mülheim coat of arms, there as a black mill iron in the right Obereck, indicates the mills that once stood here. The diagonally crossed black bishop's rods from the Kärlich coat of arms, there above the continuous red cross, refer to the fact that the electors and archbishops of Trier temporarily resided in the later destroyed Kärlich castle. |

Attractions

Old chapel at the town hall

The oldest completely preserved building in the city is the Gothic "Old Chapel" next to the town hall in Kapellenstrasse in the Mülheim district. According to documents, it was built between 1313 and 1318. The roof turret dates from the baroque period . The 14 × 5 meter building was a branch church of the Kärlich parish until the Mülheim parish church was built in the 19th century. After that it was used as a classroom, among other things. Today it serves as a party and event room as well as a meeting room for the city council.

Roman villa

Foundations of a Roman villa rustica have been preserved from the time between the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD in Mülheim-Kärlich on Jungsstrasse in the Depot district . They came to light in 1983 when the pumice was harvested and were restored in 1995 to a height of 80 cm. A mansion measuring approximately 70 × 35 meters stood on these walls. The bathing wing with underfloor heating (hypocaust) and cold water basin of this elaborately built property can still be seen.

Half-timbered houses

In Mülheim-Kärlich there are still many old half-timbered houses , some of which have been restored true to the original. This includes the electoral castle courtyard at Burgstrasse 9, which, according to a date carved above the entrance, was probably built or expanded in 1710. However, ownership documents suggest that its origins go back much further. The foundation walls of the courtyard and the outer masonry up to the upper floor consist of quarry stone on which the half-timbering is built. The inner walls of the basement are also designed as half-timbering. Under the house there are two cellars with broken stone vaults.

Fruit trail

In the corridor area "In der Pötsch" on the slope of the Rübenacher Berg, an educational fruit trail with over 250 trees and bushes was laid out in 2000. Groups and individuals can visit the facility on request from the city administration. There is also a refuge on the site.

Sacred buildings and facilities

Parish Church of St. Mauritius Kärlich

The oldest sacred building is the Catholic parish church of St. Mauritius in the Kärlich district, which is first documented in connection with the incorporation into the St. Florin monastery in Koblenz on March 10, 1217. The Romanesque east choir and wall remains of a lateral apse , which were discovered in 1976 during construction, date from this time . A Gothic chapel from the 15th century is built on the north side of the choir. In 1903 the church, the nave of which had been rebuilt in the Baroque style after it was destroyed in the Thirty Years' War, was given a neo-Romanesque bell tower 42 meters high, visible from afar from the north and west. The old nave of the church has not been preserved; it gave way to the new building built in 1931/32 by the architects Ludwig Becker and Anton Falkowski.

Parish church Maria Himmelfahrt Mülheim

The Catholic parish church Maria Himmelfahrt was built on a terrace between Bassenheimer Strasse and Bachstrasse between 1888 and 1890, and it still shapes the cityscape today. The architect of the three-aisled, neo-Gothic hall church and the rectory built in 1885 was Caspar Clemens Pickel from Düsseldorf. The church is 56.5 meters long, 34.5 meters wide and has a 60 meter high bell tower. The consecration took place on May 2nd, 1891. Mülheim, until then a church affiliate of Kärlich, was raised to an independent parish in 1887. The first pastor was Heinrich Rödelstürtz. The cost of building the new church - around 200,000 marks - was mainly raised through donations.

Parish Church of St. Peter and Paul

In June 1959, the parish of St. Peter and Paul was founded in the Urmitz-Bahnhof district, after the parish church had been built on the site of an emergency chapel between January 1957 and June 1958. This building, designed by the architects Craemer (Trier) and Hofmann (Darmstadt), was considered to be “one of the most modern in its layout and construction in the Rhineland.” The most striking architectural feature on the outside was the barrel vault, which quickly gave the building the name “ Fasskirche “and did not meet the expectations of the parishioners. The predominant use of concrete instead of the local pumice stone, which was discarded by the church authorities and largely donated, was also criticized. The modern construction turned out to be inadequate within a short time, so that the barrel vault in particular was spanned with a steel structure and a gable roof due to its leakage in 1973.

Chapel on the good man

Outside of the buildings directly on the Rhine is the Am Guten Mann chapel, which in 1838 replaced a previous building that had been destroyed in the course of the French Revolution . The architect of the new chapel was Johann Claudius von Lassaulx , whose work is indicated by the small arches below the roof on the side walls, on the altar apse and on the gable.

Friedenskirche

The Friedenskirche in Poststrasse is the church of the Protestant parish Urmitz-Mülheim. Until the end of the Second World War, only a few Protestants lived in both Mülheim and Kärlich. This only changed with the influx of expellees from the former eastern German territories . Therefore, on April 1, 1950, the Protestant Christians founded an independent congregation. Ten years later they built the Friedenskirche, which in 1964 also received a bell tower. The nearby Paul Gerhardt House serves as the community center.

Former Jewish cemetery

The former Jewish cemetery of Mülheim on the southern outskirts is one of the city's protected cultural monuments . It was laid out in the 19th century and used until the deportation of the Mülheim Jews during the Nazi era . The last funeral took place in 1941. On the 773 m² site there are 15 tombstones and a memorial stone that commemorates the extinct Jewish community and lists the names of the deported and murdered Jews from Mülheim-Kärlich.

schools

In Mülheim-Kärlich there are three primary schools as well as a school and sports center with a grammar school and a secondary school plus, which is run by the Weissenthurm community.

Christophorus School Kärlich

There is evidence of a first schoolhouse in Kärlich for 1702, which burned down in 1728. It may have been restored, because a new school building was only built in 1818 at Mülheimer Straße 10. This building was expanded in 1833 so that a class could only be set up for girls.

In 1907 the community built a new schoolhouse with teachers' apartments on the corner of Bahnhofstrasse and Burgstrasse (today Clemensstrasse and Burgstrasse). This school was only intended for boys, while the girls stayed on Mülheimer Strasse until an extension was built in 1935. A bomb that fell on the neighboring property on January 1, 1945 damaged the building so that it could not be used again until May 1945. After the end of the war, French occupation soldiers used the school for a short time. They destroyed furniture, teaching and learning materials, so that school operations with eight grade levels could not be resumed until October 1, 1945. The building was renovated several times over the next 20 years. On December 18, 1965, the Catholic elementary school in Kärlich was named "Christophorus School". A sgraffito of St. Christopher on the west side of the building was created by the painter and teacher Hermann Ruff (* 1899 in Hechingen ; † 1983 in Schweich ).

In 2012, the Neuwied Materials Testing Office found that the foundations of the old Christophorus School building were unstable and the masonry in the younger extension was too weak. Therefore, for security reasons, the building was closed to school operations and lessons were moved to mobile classrooms. At the end of 2012, the city council decided to demolish the house and build a new one. After the demolition in August 2013, the new building began in September 2015; The foundation stone was laid on November 6, 2015. After a construction period of 21 months, the new school was inaugurated on May 20, 2017 under the changed name “Primary School Christophorus”. The construction costs amounted to 4.5 million euros; the city of Mülheim-Kärlich contributed 2.3 million euros. The architect was Raphaela Adler, Weissenthurm Association. Pastor Marina Stahlecker-Burtscheidt and pastoral advisor Markus Annen as well as students blessed the new school.

The patron saint is shown in a new picture next to the main entrance to the school. It is a work by Elke Pfaffmann and Stefan Kindel from Offenbach an der Queich , whose design was selected from six applications. The lines of the representation are milled into the panels of the facade and are closed at the bottom by a narrow blue band made of enamelled sheet steel. The ribbon symbolizes the floods that Christophorus crossed with the baby Jesus on his shoulders. The map of the world on the north side, connected to the child by a line, indicates that Christ is there for all people and bears the burden of the world, which now also rests on Christophorus.

Elementary school Mülheim

The Mülheim children attended the Kärlich school until 1813. They were then taught in the half-timbered house on the corner of Kapellenstrasse and Bachstrasse, on the first floor of which a school hall was set up. In 1821 the community of Mülheim built its first school building in the Castorhof on Kärlicher Straße. There was also the teacher's apartment and a room for the fire engine. In 1878/79 a second schoolhouse was built on Poststrasse, which was supplemented in 1895 by a building next to the old chapel. Individual classes continued to use this building even after the new school was built on Annastraße in 1932. In 2015, the school in Annastraße was demolished due to significant structural defects and replaced by a new building in 2016/17.

Primary school St. Peter and Paul in Urmitz-Bahnhof

The school in Urmitz-Bahnhof was inaugurated on November 30, 1899. 63 children from eight years were taught together in just one classroom. Before that, they had to walk to school in Mülheim, Kärlich or Urmitz. By 1908 the number of children rose to 98, so that a second classroom and a teacher's apartment were added. In 1964/65 the schoolhouse was rebuilt and redesigned again in 1976. In 1989 the school was named “St. Peter and Paul ”. Like the school buildings in Kärlich and Mülheim, it was also demolished in the summer of 2014 due to safety concerns.

The new school building was inaugurated on August 11, 2018.

School and sports center

The Mülheim-Kärlich school and sports center was inaugurated in September 1979 with a five- to six-class secondary school. This school, which is also attended by students from Bassenheim , Kaltenengers , St. Sebastian and Urmitz , is the Weissenthurm association . The Realschule plus has existed in Mülheim-Kärlich since 2008 and after the summer vacation 2009 the grammar school started work with 85 students, initially as a branch of the Wilhelm-Remy grammar school in Bendorf . The grammar school has now been founded as an independent school and has been called the Mittelrhein-Gymnasium since 2017. The Realschule plus is called "Realschule plus an der Römervilla" according to the decision of the municipal council of September 2016.

Culture

Mülheim-Kärlich has a lively club life, which reaches its peak during the carnival season. Unlike the better-known Carnival strongholds in the Rhineland is in Mülheim-Kärlich not the Rose Monday , but the focus Thursday , called the Women's Carnival, the highlight of the season. The largest Möhnen club in Germany is at home in Mülheim-Kärlich . Independently of the Möhnen, every two years the Kirmes- and Carnival Society "Lust 1920" Kärlich and the Mülheim Carnival Society on Sunday and the Kirmes- und Karnevalsgesellschaft Urmitz-Bahnhof organize their Carnival parade on Shrove Tuesday.

The Mülheim-Kärlich theater and homeland association has existed since December 1919, and is best known for its annual fairy tale games in the run-up to Christmas. One of the other tasks of the association is the maintenance of local customs.

In 1978 the Kolping Family St. Mauritius Kärlich founded a theater group that has been giving up to 18 performances every year from Easter since 1984 in the parish hall of the Kärlich church. The group mainly performs tabloid comedies with which they reach audiences far beyond Mülheim-Kärlich. The Kolping Family uses the income surplus for social purposes. In May 2016, the Kolping theater group received the Mayen-Koblenz District Cultural Promotion Prize.

In September 2012 the theater group "Da Capo" Mülheim-Kärlich was founded. She presents tabloid comedies. The venue is the large hall of the clubhouse in the Mülheim district. The group shows a new piece every year, with the premiere taking place in early March. The surplus of income is used exclusively for charitable purposes in Mülheim-Kärlich.

Singing and music are maintained by the church choirs of the parishes Kärlich, Mülheim and Urmitz-Bahnhof, the male choir “Cäcilia”, MGV “Liederkranz 1904 Kärlich”, MGV “Frohsinn 1901 Mülheim”, singing group, which has been awarded the title “Master Choir of the Rhineland-Palatinate Choir Association” “Unisono” and Kolping choir “pianoforte” as well as the accordion friends “So sind wir”, Mandolin Club 1920 Mülheim-Kärlich, Musikverein “Harmonie” Urmitz-Bahnhof, Musikverein Frei-weg Mülheim and the Salon Orchestra Mülheim-Kärlich as a group of the Kolping Family.

Since 1985 the place has a small historical museum. Geological finds as well as antiquities from the Neolithic, ancient, medieval and modern times are exhibited in it. In 2003 the city museum moved into new rooms in the old school building and in the former fire station on Poststrasse. The museum is now run by the “Museumsfreunde Mülheim-Kärlich” association founded in 2003, which is dedicated to maintaining the city's historical and cultural heritage. On May 31, 2017, the museum was awarded the Mayen-Koblenz District Cultural Promotion Prize.

Sports

Several clubs offer opportunities for various kinds of sporting activities, including the gymnastics clubs TV 05 Mülheim and TV Kärlich 08/68 as well as the soccer club SG 2000 Mülheim-Kärlich 1921 e. V. This is the merger of the two clubs SSV Mülheim-Kärlich and SSV Urmitz / Bhf. B. TV Kärlich achieved its greatest sporting success to date when the club's B youth team became German handball champions in 1974 in Fürth. In 1980, TV Mülheim and TV Kärlich became the HSG Mülheim-Kärlich (handball community), in which TV Bassenheim participated from 1991. The HSG played in the second Bundesliga for three years before financial difficulties led to the dissolution in 2009. Since then, the TV Mülheim has continued the sport of handball and, like the TV Kärlich, also offers a wide range of popular sports.

In 1991 the Tauris leisure pool was opened in Mülheim-Kärlich.

Economy and Transport

Mülheim and Kärlich were traditionally characterized by agriculture. In the 19th century the mining of pumice and clay was added as an important branch of the economy. The industrial park, which has been in existence since the late 1960s, benefits from the convenient location of Mülheim-Kärlich.

Agriculture

Agriculture is still important for the place: The area around Mülheim-Kärlich represents the largest contiguous fruit-growing area in the region. Sweet cherries and morello cherries are mainly grown.

Clay mining

The clay was first extracted underground in bell shafts; however, after fatal accidents this type of dismantling was discontinued. Opencast mining began in 1892 in the pit on the Kärlicher Berg south of the then municipality and today's district of Kärlich. The raw material is delivered to customers at home and abroad as well as being burned to refractory stone in the local factory of the Kärlicher Ton- und Schamottewerke (KTS) founded in 1867 in the Urmitz-Bahnhof district. Initially, horse-drawn vehicles transported the clay from the pit to the factory, until a cable car and, in connection with it, a ship loading point on the Rhine were put into operation in 1919. In 1965 trucks replaced the cable car. Only four to five people work in the pit. With scrapers and since around 2005 instead with backhoes, dumpers and bulldozers , they mine around 50,000 tons of clay every year and then recultivate the site. Around 1900, 200 to 300 men were doing the comparable work by hand, depending on their needs.

Trade and service

Today the face of the young city is dominated by trade, services and manufacturing. During the term of office of the last Mülheim Mayor Andreas Nickenig and the first Mülheim-Kärlich Mayor Philipp Heift, an industrial park was created in 1967, in which today around 300 companies with more than 6000 jobs are located. With over 2 square kilometers, the Mülheim-Kärlich business park is one of the largest of its kind in Germany. In 2005 it was expanded to include additional areas.

Nuclear power plant

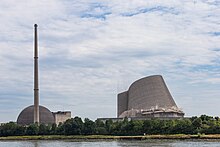

Over the last few decades, the place has become known nationwide as the location of the Mülheim-Kärlich nuclear power plant , which was designed for an output of 1,300 megawatts. Even before its construction by the RWE energy company , which began in 1975, the power plant was controversial, not least because of its location in the earthquake-prone Neuwied Basin. Because of this risk, the construction plans were changed again after the first partial approval and the reactor building was erected 70 meters away from the originally intended location. In 1986 the NPP began trial operations and in June 1988, regular operations.

Lawsuits against the first partial license were repeatedly rejected on the grounds that the second partial license issued after the plans were changed had replaced them. However, the appeal against these judgments was successful. On September 9, 1988, the Federal Administrative Court in Berlin ruled that , due to the doubts about the suitability of the location, a simple release of the plan changes through the second partial approval was not sufficient. Rather, a new construction license under nuclear law is required. Therefore, RWE had to take the power plant off the grid after almost two years in trial operation and exactly 100 days in regular operation. In 1990, the Rhineland-Palatinate state government issued a modified permit, but the Koblenz Higher Administrative Court revoked this again in 1995. The Federal Administrative Court confirmed the decision of the OVG 1998 in the last instance . In 2001 the power plant was finally shut down.

The Mülheim-Kärlich NPP is the largest of its kind in Germany to date and is being dismantled. After the uranium fuel rods were removed from the reactor block in 2002, the actual dismantling work began in 2004 and is expected to be completed by the mid-2020s. After extensive decontamination, a recycling company initially bought the power plant site, but withdrew from the purchase agreement in 2016. The further dismantling of the NPP, which is estimated to cost around 750 million euros, was delayed further. From May 2018, a special excavator, which was sitting on the edge of the cooling tower, removed it piece by piece to a height of around 80 meters. The remainder of the tower, visible for 41 years, was brought down in a controlled manner on August 9, 2019.

Urmitz train station

The first train stop in Mülheim, which was served by three passenger trains and freight trains every day, was set up in June 1870. In 1876 the station was built. Although located in the Mülheim district, the station has always been called Urmitz, as it was closer to the houses in this neighboring town and because there were already several train stations with the name Mülheim. The original intention is to bring the railway line on the left bank of the Rhine closer to the places Mülheim and Kärlich. However, this failed because the necessary land could not be acquired.

Urmitz station has two platforms that are connected by an underpass. For a long time there was only one level crossing, so that travelers had to cross the tracks depending on the direction of travel of the train. In addition to the ticket office and baggage and express goods handling, the station building also had a waiting room and a station restaurant . The station had two signal boxes and a goods handling facility for general cargo and wagon loads, which was housed in a separate building about 250 meters to the west.

Since 1992 tickets have only been issued from machines. Operationally, however, it is still a train station with tracks to avoid. The old station building has been privately owned for a long time and was renovated in 2013 in the run-up to the “station festival” of the city of Mülheim-Kärlich. The Urmitz goods handling no longer exists.

Personalities

Born in Mülheim-Kärlich

- Dominikus I. Conrad (1740–1819), last abbot of the Cistercian Abbey of Marienstatt before it was secularized in 1802

- Philipp Heift (1928–2002), first mayor of Mülheim-Kärlich and honorary citizen

- Ernst Ludwig Grasmück (1933–2017), church historian

- Georg Nickenig (* 1964), cardiologist

Associated with Mülheim-Kärlich

- Johann Claudius von Lassaulx (1781–1848), architect, built the Chapel Am Guten Mann in 1838

- Caspar Clemens Pickel (1847–1939), architect; built the Mülheim parish church Maria Himmelfahrt

- Ludwig Becker (1855–1940), church architect and master builder of the cathedral; New parish church of St. Mauritius 1931–1932

- Ludwig Kaas (1881–1952), chairman of the Center Party ; 1910 Chaplain in Kärlich

- Martine Andernach (1948–), German-French sculptor and engraver, lives and works in Mülheim-Kärlich

literature

- Franz Petri: Rhenish history . Ed .: Georg Droege. Schwann Verlag, Düsseldorf 1976 (3 volumes with illustrated and document volumes).

- Winfried Henrichs (Ed.): Mülheim-Kärlich . Mülheim-Kärlich 1981.

- Franz-Josef Risse and Lothar Spurzem: Parish and Parish Church of St. Mauritius Kärlich . Mülheim-Kärlich 1991.

- Peter Schuth: Mülheim-Kärlich and its past (looking for traces) . Mülheim-Kärlich 2001.

- Winfried Henrichs: City chronicle Mülheim-Kärlich . Mülheim-Kärlich 2009.

- Franz-Josef Baulig among others: Our home . Ed .: TomTom Press Agency. Mülheim-Kärlich 2019 (publication on the occasion of 50 years of Mülheim and Kärlich).

Web links

- Website of the city of Mülheim-Kärlich

- city Museum

- Historical information about Mülheim-Kärlich at regionalgeschichte.net

- Historical information about Urmitz at regionalgeschichte.net

- Link catalog on the subject of Mülheim-Kärlich at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Literature about Mülheim-Kärlich in the Rhineland-Palatinate state bibliography

Individual evidence

- ↑ State Statistical Office of Rhineland-Palatinate - population status 2019, districts, communities, association communities ( help on this ).

- ↑ State Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate - regional data

- ↑ Winfried Henrichs (Ed.): Mülheim-Kärlich. Pp. 55-57, Mülheim-Kärlich 1981.

- ↑ Journal of English and Germanic philology 56 (1957), p. 315; Walter Baetke : The sacred in Germanic. Tübingen 1942, pp. 155-165.

- ^ Henrichs: City Chronicle. P. 74.

- ^ Petri, Droege (HG): Rheinische Geschichte. Image u. Documentary volume, p. 352.

- ^ Winfried Henrichs: Country population and agriculture in the 18th and 19th centuries. In: Winfried Henrichs (Ed.): Mülheim-Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 1981, pp. 153-158.

- ↑ Winfried Henrichs: The mountain slide catastrophes of 1896/97 and 1906. In: Winfried Henrichs (ed.): Mülheim-Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 1981, pp. 163-169.

- ↑ Lt. Col. George Dyer: XII Corps Spearhead of Patton's third Army.

- ^ LIFE Magazine, April 2, 1945.

- ^ Henrichs: City Chronicle. Pp. 370-373.

- ↑ State Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate - Official municipality directory 2006. ( Memento from July 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). Pages 188 and 204 (PDF; 2.1 MB).

- ^ Homepage of the city of Mülheim-Kärlich . Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ The Regional Returning Officer of Rhineland-Palatinate: direct elections 2019. see Weißenthurm, Verbandsgemeinde, fourth line of results. Retrieved November 10, 2019 .

- ^ Winfried Henrichs: City Chronicle Mülheim-Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 2009, pp. 75-77.

- ^ Winfried Henrichs: City Chronicle Mülheim-Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 2009, p. 50.

- ↑ Dr. Dieter Mannheim: The electoral castle courtyard ... In: Winfried Henrichs (Ed.): Mülheim-Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 1981.

- ↑ Horst Hohn: Delicious local history in the Mülheim-Kärlicher fruit nature trail. In: Heimatbuch des Landkreises Mayen-Koblenz 2006. pp. 147–148.

- ^ Risse, Spurzem: Parish and Parish Church of St. Mauritius Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 1991, pp. 9-13.

- ↑ Winfried Henrichs: 100 years parish Maria Himmelfahrt Mülheim. Mülheim-Kärlich 1987, pp. 89-103.

- ^ Rhein-Zeitung . 14./15. June 1958.

- ↑ Winfried Henrichs: 100 years parish Maria Himmelfahrt Mülheim. Parish Mülheim, Mülheim-Kärlich 1987. pp. 137–142.

- ^ Mülheim-Kärlich community (ed.), Josef Schmitt: Mülheim-Kärlich. 1981, pp. 241 and 246.

- ^ Website of the Evangelical Church Community

- ↑ Presbytery of the Evangelical Church Community Mülheim-Kärlich (ed.), Martin Hentze: 50 years of the Evangelical Church Community Urmitz-Mülheim. Anniversary publication, 2000, p. 20.

- ↑ Schools. Retrieved May 26, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Winfried Henrichs: Development of the school system. In: Mülheim-Kärlich. Published on behalf of the municipality of Mülheim-Kärlich, Mülheim-Kärlich 1981, pp. 208–212.

- ^ Lothar Spurzem: Christophorus at the Kärlicher School . In: Landkreis Mayen-Koblenz (Hrsg.): Heimatbuch 2015 . Wochenspiegel Verlag, 2014, ISSN 0944-1247 , p. 175 f .

- ^ Damian Morcinek: Kärlich receives a new elementary school. In: Rhein-Zeitung. December 1, 2012, p. 15.

- ↑ Peter Karges: Foundation stone laid for Kärlicher school. In: Rhein-Zeitung. November 7, 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Peter Karges: First elementary school officially opened. In: Rhein-Zeitung. No. 118, edition BO of May 22, 2017, p. 28.

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: current view. No. 21/2017 of May 23, 2017, Weißenthurm edition, p. 33.

- ↑ Albert Weiler: For the children of our city! In: Stadtjournal Mülheim-Kärlich. Edition November 2016, TomTom PR Agency, p. 48 u. 49.

- ↑ Damian Morcinek: Demolishing primary school will be expensive. In: Rhein-Zeitung. January 13, 2016.

- ↑ Ernst Meyer: The school in Urmitz-Bhf. In: Mülheim-Kärlich. Published on behalf of the municipality of Mülheim-Kärlich, Mülheim-Kärlich 1981, p. 212.

- ↑ Damian Morcinek: The history of the elementary school should be preserved. In: Rhein-Zeitung. June 20, 2014, p. 27.

- ^ Homepage of the elementary school St. Peter and Paul. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ Rhein-Zeitung. August 14, 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Rhein-Zeitung. April 15, 2009, p. 17.

- ↑ Middle Rhine High School. Mülheim-Kärlich. Retrieved April 8, 2017 .

- ^ Mülheim-Kärlich school center: Schools are given names. In: Rhein-Zeitung. September 23, 2016, accessed April 8, 2017.

- ↑ Theater Exchange . Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ Homepage of the theater and homeland association Fidelio. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ↑ Thomas Krämer: The MYK district honors the Kolping Theater and “Lehmenart” with a cultural sponsorship award. In: Rhein-Zeitung. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Homepage of the city of Mülheim-Kärlich. List of clubs. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ Rhein-Zeitung. Edition BO, Koblenz, June 3, 2017, p. 19 ( page no longer available , search in web archives: e-paper ).

- ^ Homepage of the city of Mülheim-Kärlich. ( Memento of July 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Homepage of TV Kärlich 08/68.

- ↑ Dr. Dieter Mannheim: On the history of clay mining in our community. In: Winfried Henrichs (ed.): Mülheim-Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 1981, pp. 334-338.

- ↑ 150 years of KTS Kärlicher Ton- und Schamottewerke Mannheim & Co. KG. Company chronicle for the anniversary, Mülheim-Kärlich 2017.

- ↑ Horst Hohn: The last mayor of Mülheim. In: Heimatbuch des Landkreises Mayen-Koblenz 2007. P. 138.

- ^ Winfried Henrichs: City Chronicle Mülheim-Kärlich. Mülheim-Kärlich 2009, p. 320.

- ↑ The father of the business park is dead. In: Rhein-Zeitung. September 4, 2002, p. 21.

- ↑ Timo Hohmut: The development of nuclear law in Germany since 1980. Presentation, analysis of materials. Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2014, p. 40 f.

- ^ Daniel Wetzel: Mülheim-Kärlich. This is how you make a nuclear power station disappear. In: welt.de . June 11, 2014, accessed October 7, 2018 .

- ↑ The dismantling of the power plant is delayed. Only 16 meters are away from the nuclear power plant cooling tower in Mülheim-Kärlich. In: SWR.de . December 12, 2018, accessed February 10, 2018 .

- ^ Nuclear power plant dismantling in Mülheim. Tower falls! In: FAZ.de . August 9, 2019, accessed August 9, 2019 .

- ^ City of Mülheim-Kärlich (ed.), Winfried Henrichs: City Chronicle Mülheim-Kärlich. 2009, p. 306.

- ^ Ewald Dähler: The Urmitz train station. In: Mülheim-Kärlich municipality (ed.): Mülheim-Kärlich. 1981, pp. 320-323.

- ^ Rhein-Zeitung. Mittelrhein-Verlag Koblenz, September 17, 2013, p. 22.