Mogontiacum

Mogontiacum (also Moguntiacum ) is the Latin name of today's city of Mainz , which it bore during its almost 500-year membership of the Roman Empire . Mogontiacum had its origin in the 13/12 BC. A legionary camp built by Drusus in the 3rd century BC , which was strategically located on a hill above the Rhine and opposite the mouth of the Main on the Roman Rhine Valley road .

The civil settlements ( vici ) spreading down the Rhine in the vicinity of the camp quickly grew together to form a larger, urban settlement. However, in contrast to Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne) or Augusta Treverorum (Trier) , Mogontiacum was primarily a military site until the second half of the 4th century and was apparently also not a colonia . As a result, the city never had the urban character of the other large Roman cities in Germany. Nevertheless, several monumental buildings were erected here too, because Mogontiacum was the provincial capital of the Roman province of Germania superior with the seat of the governor from the year 90 at the latest . After the middle of the 3rd century, when the Dekumatland was cleared, Mogontiacum became a border town again and over the next 150 years it was repeatedly devastated by members of various Germanic tribes . After the end of the Roman period, but no later than 470, Mogontiacum belonged to the Franconian Empire after a brief transition phase .

In today's city of Mainz, some significant remains of Mogontiacum have been preserved, for example the Roman stage theater , the Great Mainz Jupiter Column , the Drusus stone and the Roman stones , remains of the aqueduct of the legionary camp. The Roman-Germanic Central Museum , the Landesmuseum Mainz and the Museum für Antike Schifffahrt keep a large number of finds from Mainz's Roman times.

Naming

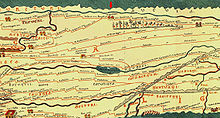

The name Mogontiacum is made up of the Celtic name Mogo (n) , the Celtic suffix -ontiu- (as in Vesontio / Besançon ) and the affiliation suffix * -āko , Latinized to - (i) acum . It thus contains the name of the Celtic god Mogon as a component . The name could have been given to the Celtic settlement of the Aresaks , a sub-tribe of the Treveri , in the immediate vicinity of the legionary camp . These were located at the end of the first century BC in the area of today's Mainz-Weisenau and Mainz-Bretzenheim . Mogontiacum was first mentioned in the historiography by the Roman historian Tacitus in his early 2nd century work Histories in connection with the Batavian Rebellion . The derived spelling Moguntiacum is also common . Abbreviations and different spellings were also common during the Roman rule. In the Tabula Peutingeriana , Moguntiacum was written shortened to Moguntiaco . Epigraphically , the city name can be traced for the first time on a milestone from the Claudian era.

history

The almost 500-year-old Roman history of Mogontiacum can be divided into four sections: The first period begins with the foundation of the city towards the end of the 1st century BC BC and ends with the establishment of the province Germania superior and the appointment of Mogontiacum as the provincial capital. The period between 90 AD and 260 AD covers the heyday of the city until the end of the Limes , with which Mogontiacum again became the border town of the Roman Empire. In the third period from 260 to 350 there are profound changes in the city in view of the internal turmoil in the Roman Empire and the increasing threat from Germanic warriors. The end times from AD 350 to AD 470 reflects the decline of the city, which was plundered and devastated several times during this period.

Foundation of Mogontiacum and history up to Domitian (13/12 BC to 90)

In the course of the expansion efforts of Augustus from 16 BC His stepson Nero Claudius Drusus also penetrated the Middle Rhine and secured the area for the Roman Empire. No later than 13/12 BC BC, possibly even earlier, a double legion camp was built on a hill above the Rhine and opposite the mouth of the Main. The military presence of the Romans at this point primarily secured control over the Middle Rhine, the Main estuary and generally over the Main as one of the main routes of incursion into free Germania.

At the same time, another military camp was built just under four kilometers south of what is now the Mainz district of Weisenau . This was mostly occupied by auxiliary troops, but was temporarily used for the stationing of other legionaries . One of the late La Tène Age Celtic settlements in the Mainz area was also located there. The native Celtic population belonged to the Aresaks, a sub-tribe of the Gallic Treveri , who were here in their most eastern settlement area.

Until the annexation plans were abandoned in 16, Mogontiacum served several times as a base for military operations as part of the Drusus campaigns (12 to 8 BC), the campaign against the Marbod Empire (6 AD) and the Germanicus campaigns (14 to 16 AD) in the Germania on the right bank of the Rhine. For the 9 BC After Drusus , who died in the 4th century BC , legionaries in Mogontiacum erected a cenotaph in the immediate vicinity of the legionary camp, which is likely to be identical to the Drususstein still existing today on the Mainz citadel . As early as the times of the Drusus, a ship bridge was built above the mouth of the Main to cross the Rhine. In the first decade of the 1st century BC The bridgehead Castellum ( Castellum Mattiacorum ) on the right bank of the Rhine was founded and expanded, which became the nucleus of today's Mainz-Kastel (derived from the Latin castellum ). The construction of a solid wooden bridge ( Pfahljochbrücke ) between Mogontiacum and Castellum can be dated to the year 27 .

After the restructuring of the Roman Rhine Army into an Upper and a Lower German Army in 17, Mogontiacum became the seat of the commander of the Upper German Army. In addition to the rapidly developing camp suburbs (canabae legionis) in the south and southwest of the legionary camp, various civilian settlements (vici) emerged , which stretched eastward down to the Rhine and possibly slowly merged into a coherent settlement structure as early as the 1st century. As early as the first half of the 1st century, Mogontiacum had large civil buildings with a larger public thermal bath and a theater mentioned by the Roman writer Suetonius . The Great Mainz Jupiter Column , dated to the third quarter of the 1st century, was donated by an apparently wealthy, larger civil community and can be taken as evidence of the rapid progress of the civil development of Mogontiaum. In spite of the beginning of the formation of civil structures, Mogontiacum remained one of the most important military bases of the Roman army on the Rhine. Two legions including auxiliary troops and entourage were permanently stationed in Mogontiacum and in the second military camp in Weisenau, which had been expanded since the rule of Caligula . In addition, more troops were stationed as required - such as after the Varus Battle , when three legions were temporarily stationed in Mogontiacum.

During the Batavian uprising , most of the civil buildings outside the legionary camp were destroyed. According to Tacitus, the camp itself was besieged without success. Extensive construction work was carried out in Mogontiacum under the rule of the Flavian imperial family. The legionary camp was rebuilt in stone under Vespasian , and the wooden pile yoke bridge was replaced by a pile grate bridge with stone piers. During the reign of Emperor Domitian , a stone-built aqueduct replaced a previous wooden building. The aqueduct led over a distance of nine kilometers of fresh water from the springs of today's remote Mainz districts of Finthen (Fontanetum) and Drais to the legionary camp on the Kästrich.

83, the city was the starting point for the chat campaign Emperor Domitian. For this purpose he gathered an army of five legions and auxiliary troops in Mogontiacum. In 88/89 the governor Lucius Antonius Saturninus rebelled in Mogontiacum. After the rapid suppression, the previously planned and now finally completed conversion of the military territory into the province of Germania superior with Mogontiacum as the provincial capital (caput provinciae) took place .

Provincial capital and important military base on the Rhine (90 to 260)

The process of transforming the military territory into the province of Germania superior began in the mid-80s of the 1st century and was fully completed by mid-90 at the latest. A military diploma dated October 27, 1990 is considered the earliest epigraphic evidence of the newly established province. With Lucius Iavolenus Priscus , the province was given a consular governor who was already experienced as a suffect consul and who was supposed to quickly develop the necessary civil structures. Beginning under Domitian and continuing under his successors, the Romans secured areas on the right bank of the Rhine to protect the new provinces and to round off the territories. With the permanent occupation of the Neuwied Basin , the Taunus and the Wetterau , the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes was created . Mogontiacum took over the important task of the military administrative center for the Upper German Limes section until its collapse.

There were also lasting changes for Mogontiacum itself: For example, based on the experience of the uprising of Saturninus, the number of permanently stationed legions was reduced from two to one. Since the year 92 this was the Legio XXII Primigenia , which from then on remained the sole Mainz house legion until it was destroyed in the middle of the 4th century. From 96 to 98 the future Emperor Trajan held the office of governor of the province; and Hadrian , his successor was, as part of its previously completed military career as a military tribune been stationed in the province. A time of peace and prosperity dawned for Mogontiacum. The border to free Germania was pushed far forward and secured by the ever more elaborate Limes. Trade and handicrafts flourished in the city and throughout the surrounding area, where many veterans of the military forces settled. The incursion of the Chatten into the Rhine-Main area in 162 and again in 169, as well as the crossing of the Rhine that took place in the process, initially remained one-time events with no major impact.

It was to take until March 19th (?) Of the year 235 before Mogontiacum should come back into the focus of Roman world history. In preparation for a campaign against the Alemanni , the emperor Severus Alexander gathered troops in Mogontiacum. There he and his mother Julia Mamaea were murdered in or near Mogontiacum in the vicus Britannicus ( Bretzenheim ?) During unrest by Roman legionaries. This was immediately followed by the proclamation of the military commander Gaius Iulius Verus Maximinus (with the nickname Thrax, which was later acquired ), as his successor. This was the beginning of the era of the soldier emperors , which also included the time of the imperial crisis of the 3rd century .

Around the year 250 or a little later, the civil settlement was surrounded by a city wall towards the Rhine. This included the entire previously populated area and the large stage theater , but not the camp canabae to the southwest. This first city wall extended to the fortified legion camp in the southwest of the city, which supplemented the city wall at this point with its own fortification. Since the so-called Limesfall is generally only dated to the year 259/260, the two events are not, as previously assumed, directly related to one another. Rather, the presence of the Roman troops, who repeatedly had to deploy larger detachments for campaigns in distant areas and were distracted by a series of civil wars, was no longer regarded as sufficient to protect the city against looters. With the abandonment of the Upper German Limes, Mogontiacum became a border town again - despite further claims on the right bank of the Rhine such as the Castellum bridgehead or the thermal baths in the neighboring Aquae Mattiacorum ( Wiesbaden ).

Mogontiacum as a border town after the Limesfall (260 to 350)

Almost simultaneously with the "Limesfall" there was another major change in the political situation that directly affected Mogontiacum. After Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus had succeeded in combining parts of the Roman Empire into the so-called Imperium Galliarum (also: Gallic Sonderreich), Mogontiacum also belonged to this state structure until 274. In Mogontiacum in 269 the Laelianus legate proclaimed himself anti-emperor against Postumus. Although Postumus defeated Laelianus in the civil war that followed and recaptured Mogontiacum, he died immediately afterwards at the hands of his own soldiers, as he did not want to give up the city for sacking. From 274 the Imperium Galliarum no longer existed: Mogontiacum belonged again to the Roman Empire.

In the course of the Diocletian reforms and especially after the reorganization of the Roman provinces from 297 onwards, the province of Germania superior merged into the (smaller) new province of Germania . Mogontiacum remained the seat of the provincial governor. In addition, the city functioned a little later as the seat of two military commanders, the Dux Germaniae primae and the Dux Mogontiacensis , to whom the border army was subordinate to this section of the Rhine border. The first pictorial view of Mogontiacum on the so-called Lyons lead medallion also dates from around the year 300 . This shows the walled Mogontiacum, the fixed Rhine bridge and the bridgehead Castellum on the right bank of the Rhine.

Decline of the city (350 to 450)

Around 350 a second city wall was built due to the increasingly unstable political situation. The military camp, like the stage theater, was now outside the secured urban area, and both facilities were demolished. In the following years there were repeated incursions by Germanic groups, especially Alemanni, who were even able to establish themselves temporarily on the left bank of the Rhine. The background was probably a renewed civil war in the Roman Empire: In the fighting between the emperor Constantius II and the usurper Magnentius in 351 the 22nd legion was almost completely wiped out in the bloody battle of Mursa and was not set up again afterwards. The protection of the city and the surrounding area was now taken over by the milites Armigeri , possibly a still existing unit of the largely worn-out legion. In 368, during a great Christian festival, the city was taken and sacked by the Alemanni under their leader Rando .

Mogontiacum was not spared from the consequences of the so-called " migration of peoples " that began around 376 . Endless civil wars led to another neglect of border defense. After 400, many regular Roman troops were withdrawn from the Rhine to Italy to take part in the fight against rebellious Visigoth foederati . Perhaps in connection with the Roman civil wars and probably on New Year's Eve 406, vandals , Suebi and Alans then crossed the Rhine at Mogontiacum, presumably using the Rhine bridge that was still intact at that time, and plundered and destroyed the city (see also Rhine crossing from 406 ) . There was a temporary collapse of the Roman border defense, and the Roman Rhine fleet also ceased to exist at this point.

Around 411 Mogontiacum was under the influence of the Burgundian Warrior Association , with whose support the usurper Jovinus was elevated to Roman emperor (possibly in Mogontiacum), who was only able to hold out for a short time. The Burgundians themselves were settled as Roman foederati up the Rhine in 413 (with a focus on Worms / civitas Vangionum ); From then on they monitored the border together with regular Roman units. Their sphere of influence was attacked by the Romans as early as 436 and destroyed by Hunnic auxiliaries, the survivors were resettled in 443 in Sapaudia (roughly today's Savoy ). When Attila invaded Gaul in 451 , the Huns crossed the Rhine at Mogontiacum. The city remained relatively unscathed, but after this event, at the latest in the late 460s, the official Roman rule over Mogontiacum ended. Civilian Roman structures remained in the partially destroyed city, and ecclesiastical representatives of the Mogontiacum bishopric may have taken on administrative tasks. After the Battle of Zülpich in 496 at the latest , Mogontiacum no longer belonged to the Alamanni. The city now became part of the Frankish Empire under Clovis I.

Military importance

In the historical view of the city's founding and development of Mogontiacum, it is largely agreed that the legionary camp was founded in 13 BC. BC was both the impulse and the nucleus for the later civil settlement. Celtic settlements of the late Latene period, which existed in Mainz-Weisenau and Mainz-Bretzenheim, were of no further importance for the development of Mogontiacum and either emerged at the same time as the Roman presence began or existed for a short time.

Mogontiacum's military importance continued into the first half of the 5th century. It was the location of Roman legions for more than 350 years and was the starting point for campaigns in the Magna Germania until the middle of the 3rd century, sometimes even in the 4th century. For example, campaigns by Drusus, the chat campaign of Domitian or the planned campaign of Severus Alexander against the Alemanni in Mogontiacum began. Maximinus Thrax also led his troops far into Germania after his proclamation as emperor 235 in Mogontiacum as part of the Germanic campaign 235/236 and fought there against Germanic troops ( Harzhorn event ).

From the end of the 1st century Mogontiacum was the administrative and supply center of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. After the fall of the Limes, Mogontiacum was an important border town and the site of a Roman legion and seat of the dux Mogontiacensis until the middle of the 4th century . Mogontiacum's military character is also evident in the lack of city status of the civil settlement . Nevertheless, it developed relatively quickly from the beginning of the 1st century and in the next few centuries showed a clearly metropolitan character due to population figures, trade and services as well as official buildings.

Legion and military camps

That of Drusus 13/12 BC The military camp, which was founded in BC, was one of the two main starting points for the planned campaigns in Magna Germania on the right bank of the Rhine. The choice of the location, known today as Kästrich (derived from the Latin castra ), was determined solely by strategic considerations: The Kästrich is a high plateau above the banks of the Rhine that slopes steeply on three sides, 120 m above sea level and is slightly offset from the mouth of the Mains lies in the Rhine.

The legionary camp was intended to accommodate two Roman legions (around 12,000 men) from the early Principate's time . Due to the large number of troops during the campaigns, another military camp was built in Mainz-Weisenau. Primarily auxiliary troops were stationed there, at times also other legion troops.

The legionary camp on Kästrich was built using wood and earth technology. It was laid out polygonally and covered an area of around 36 hectares. The camp was structurally changed as early as in Augustan times and repeatedly in the following years. Under Vespasian , the legionary camp was completely rebuilt in stone. A total of five different renovation and expansion phases can be archaeologically documented today. After the withdrawal of the second legion from 89 onwards, the 22nd legion remained alone in the legionary camp. Experts are still discussing whether the area that has become free was used for the construction of the governor's palace and other administrative buildings. With the construction of the second city wall around 350 and the simultaneous numerically decreasing presence of Roman troops in Mogontiacum, the legionary camp was abandoned. It was now outside the city wall and was demolished. Spolia from buildings from the camp were found in numerous forms when the foundations of the city wall were torn down, especially at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. The so-called "Mainz Octagon" should be mentioned as a representative building, which can be at least partially reconstructed from extensive spolia finds that are now stored in the Mainz State Museum. According to recent research, it is assigned to a gate construction similar to the Trier Porta Nigra . Possibly it is the monumental Porta praetoria facing the Rhine side . The architectural parts can be dated to the last quarter of the 1st century by building inscriptions. The same applies to a large pillar hall with a central passage, which was possibly part of the praetorium .

Early 20th century was in the green belt of Mainz Oberstadt the thermal bath unearthed the camp and documented. Also known are the course of the wall walls and, due to the well-known road courses, the locations of the four gates of the camp. During the excavations on the site of today's university clinics (building 501), parts of the internal production facilities (fabrica) with large structures, paved access roads and melting furnaces were excavated and documented. To the south and south-west of the camp were two separate and later merged camp villages (canabae legionis) .

The second military camp in Mainz-Weisenau was also built on a plateau above the Rhine, roughly at the height of the present-day quarry of the Heidelberg cement works . Due to finds made there, it was mostly occupied by auxiliary troops who belonged to the legions in the main camp. The camp was expanded several times, for example under Caligula when he was planning a campaign in 39 Germany on the right bank of the Rhine. In its largest expansion phase, the warehouse had a total size of twelve hectares. With the withdrawal of the second legion in 89 and due to the changed political situation, a second military camp was no longer needed in Mogontiacum and the camp was abandoned. Due to the current situation - the site in question has been used as a quarry since the middle of the 19th century - no traces of the camp can be traced.

Another military camp for auxiliary troops on the Hartenberg is suspected, but has not yet been proven archaeologically.

Stationed troops

Most of the Roman troops stationed in Mogontiacum can be identified through epigraphic legacies such as brick stamps, tombs (only 1st century) or building inscriptions; to a lesser extent, individual Roman troops stationed are also mentioned in historiography, for example in Tacitus or in the late antique Notitia dignitatum .

A total of nine different legions were stationed in Mogontiacum during the Principate's time. Between the years 9 and 17 the troop presence reached its peak with four legions stationed at the same time, including the auxiliary troops belonging to them, with an estimated 50,000 soldiers. From the year 93 the Legio XXII Primigenia Pia Fidelis (later with the honorary names Antoniniana, Severiana and Constantiniana Victrix) was the only legion to occupy the legion camp until the middle of the 4th century, possibly in parts until the beginning of the 5th century. The Notitia dignitatum, which is dated to the first third of the 5th century, names the milites armigerie , probably a kind of citizen militia , for the end times of the Roman Mogontiacum . This was stationed within the urban area and was subordinate to the Dux Mogontiacensis or a Praefectus militum armigerorum Mogontiaco .

In addition to the legions, auxiliary troops were also stationed in Mainz. Up to the beginning of the 5th century, 13 different ales and 12 cohorts have been recorded . From the second half of the 2nd century, four different numbers are also known for Mogontiacum .

Base of the Rhine fleet

Shortly after the establishment of the legionary camp and the beginning of the civilian settlement of today's urban area, several port facilities were built on the banks of the Rhine. Historical sources and archaeological finds equally prove the great importance of Mogontiacum as a military and civil port city on the Rhine.

The first archaeological finds from the middle of the 19th century on military port facilities were made in the context of the expansion of the banks of the Rhine and the emergence of the Mainz Neustadt . In addition to numerous civilian finds, pieces of military equipment were also found at “Dimesser Ort”, near today's customs and inland port. Remnants of a massive pier made of cast concrete and structural remains further down the Rhine, which could possibly be assigned to a Roman Burgus , were also found. Similar architectural structures of later times have been interpreted in other places as river war ports . In addition, the river basin, protected by a massive pier and a distant Burgus standing in the middle of the Rhine on the Ingelheimer Aue, could be equated as a military port area with the well-known main port of the Roman Rhine fleet in Cologne-Alteburg.

A second Roman military port was located up the Rhine on the Brand (near Mainz Town Hall, old town ). Due to the structural remains discovered there as well as the Roman military ships found in 1980/1981 , including the Navis lusoria type , the identification as a naval port was clearly identifiable. Here, too, ship basins separated from the Rhine were located in several construction phases, which followed the shifting of the bank of the Rhine eastwards. The main use of this war port was in the second half of the 3rd and 4th centuries, when the Rhine again became the border of the province Germania superior / Germania prima. At this time, warships patrolled the Rhine from Mogontiacum until the Roman Rhine fleet disbanded after the German invasion of 406/407 at the beginning of the 5th century.

Remains of bank fortifications and a shipyard from years 5 to 9, which was most likely used by the military at the time, were found further up the Rhine at Neutorstrasse / Dagobertstrasse . Inscriptions also name members ( signifer / flag bearers) of the 22nd Legion as overseers of navalia's ship houses and mention a separate district of the navalia .

The civil Roman Mainz

From its foundation in the 2nd decade before Christianity until the middle of the 4th century, Mogontiacum was primarily one of the largest and most important military bases on the Rhine. This led to a clear military dominance of the civilian settlements that arose around the legionary camp and around the second military camp in Weisenau. Nevertheless, in the 2nd and 3rd centuries between the legionary camp and the Rhine bridge, an increasingly urban infrastructure developed through the merging of individual vici and, at the latest after the first city wall was built in the middle of the 3rd century, a Roman civilian settlement with a large urban character.

Legal status of the city in the Roman Empire

Despite the development of urban structures, including through large buildings and the function as provincial capital from the year 90, Mogontiacum did not have an official city title such as Colonia , Municipium or Civitas . The civil settlement still had the status of a canabae legionis , so it was not a city in the legal sense. It was under the jurisdiction of the legionary legate or the governor. The inhabitants of Mogontiacum also referred to themselves as Canabarii in the foundation inscription on the Jupiter Column in Mainz . The same was evidently true for the civilian settlements near the Bonn, Strasbourg and Regensburg legion camps.

It was first mentioned as a civitas in the years of the first tetrarchy (after 293 to 305), i.e. at a time when these differentiations of the city titles had already been more or less dissolved by the general granting of Caracalla's citizenship ( Constitutio Antoniniana in 212) . Under Diocletian Mogontiacum is mentioned as a metropolis in the province of Germania. Ammianus Marcellinus designated Mogontiacum 355 as a municipium Mogontiacum .

Provincial capital Mogontiacum of the province Germania superior

After Tiberius renounced the permanent occupation of Magna Germania with the desired Elbe border, the organization of the areas on the left bank of the Rhine remained in a provisional administrative stage. The administrative district of the Upper German Army (exercitus superior) was merged with the administrative center of Mogontiacum. The administration and in particular the financial management were under the administration of the province of Gallia Belgica .

Under Domitian there was both a larger and permanent area expansion to the right bank of the Rhine ( Agri decumates ) and the establishment of a new province, Germania superior . It belonged to the imperial provinces and with an area of 93,500 km² was one of the medium-sized provinces of the Roman Empire. The already existing civil settlement Mogontiacum was raised to the provincial capital at the same time without the legal status of the settlement changing. The previous military commander of the Upper German Army Group ( legatus Augusti pro praetore) , who was also responsible for civil administration, became consular governor of the newly founded province, to which, as usual, the troops stationed there were still subordinate.

During the restructuring of the Roman provinces under Diocletian after 297, Germania superior became the much smaller province Germania prima . Mogontiacum remained the seat of the governor, as a mention of Mogontiacum as a metropolis in the Notitia Galliarum shows. The post of dux Mogontiacensis, newly created during the reign of Diocletian as the military leader of all troops on the Upper Rhine, also resided in Mogontiacum.

Camp village and civil settlement

|

Districts of Mogontiacum

|

At the same time as the legionary camp on the Kästrich was built, two canabae, initially separated from the camp, were built in Augustan times on the plateau adjacent to the south and southwest . In contrast to the civil settlement areas, these were semi-military. In Flavian times, as in the civil vici, there was an extensive expansion of the canabae in stone. Also in the 2nd century both canabae grew and mostly merged into one settlement, only separated by the aqueduct at the southwest corner of the camp. When the camp wall was renewed in the middle of the 3rd century after the fall of the Limes, the canabae were also surrounded by a protective wall. With the abandonment of the legionary camp a century later and after the destruction of the following years by Chatti and Alemanni, the canabae were also given up and abandoned. Cellar pits and a right-angled road system as well as civil burials on nearby burial sites are archaeologically proven.

Shortly thereafter, individual, separate, vici emerged below the legionary camp . The earliest archaeological evidence of civil settlement from Augustan times can be found directly in front of the Porta praetoria (today's Emmerich-Josef-Straße ). Along the Roman road leading from there to the Rhine crossing (today Emmeransstraße), this vicus slowly expanded in the direction of today's Schillerplatz and the flax market. At the flax market, a second main street coming from the military camp in Weisenau met the first street mentioned. Other civilian settlements that arose immediately after the beginning of the Roman presence were located in front of the military camp in Weisenau and at Dimesser Ort. The latter vicus is considered to be the most important civil settlement and the center of civil life in Mogontiacum in the first century AD. As a presumed settlement of long-distance trade merchants, the canabarii seem to have quickly achieved a certain level of prosperity, which was linked to the desire for legal recognition of the civil settlement. The foundation of the Great Mainz Jupiter Column in the first third of the 1st century is variously interpreted as an attempt by the civilian population to speed up the legal recognition of the settlement.

With the reconstruction of the destroyed civil settlement areas after the Batavian uprising and the expansion of the infrastructure in the following time, the individual vici slowly merged into a coherent, urban settlement area. In addition, for the time of the Flavian emperors and again increasingly from the 2nd century for the Weisenauer vicus and for the vicus am Dimesser Ort, a settlement shift towards today's inner city could be proven. The civil settlement, now centrally located below the legionary camp, extended from the foot of the Kästrich to the Rhine. Since there was no coherent construction plan, the road network that has been documented so far was not laid out regularly. Central areas of the city center were probably the flax market, where the forum is sometimes suspected, the Schillerplatz as a flood-protected settlement area and today's cathedral area, in which the central cult district is assumed.

After the construction of the second city wall in the middle of the 4th century, the urban area covered 98.5 hectares. A larger thermal bath building in the immediate vicinity of today's State Theater from the first half of the 1st century is known for the civil settlement . A larger administrative building stood in the immediate vicinity of today's urban retirement home. During construction work in the 1970s, extensive architectural remains, a marble fountain with a bronze fish figure as a gargoyle and bricks with the stamp of the Mainz legions were found. The governor's palace is presumed to have stood above the banks of the Rhine, as representative as its Cologne counterpart. Luxurious city villas were uncovered in the area of Schillerstraße at today's Proviant-Magazin as well as in the old town (Badergasse), some with mosaic decorations.

There are no data or estimates about the population of Mogontiacum. The somewhat smaller civil Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium had around 30,000 inhabitants around the year 50. Only the size of the stage theater, which could accommodate around 10,000 spectators, and the general urban development allow certain conclusions to be drawn about a possible civilian population, which should have been in the lower five-digit range.

The topography of the civil Mogontiacum is insufficiently archaeologically developed and, compared to other important Roman cities in Germany, little researched. There are different reasons for this. From the early Middle Ages onwards, the high-quality Roman building material was continuously reused for the structurally expanding city. There was also a deliberate destruction of Roman remains over and over again. For example that of the stage building at the stage theater during the construction of the railway at the end of the 19th century or that of the Mithräum on the ball court , which took place in 1976 despite protests from the population. In general, there was intensive overbuilding of the Roman settlement area in today's urban area from the Middle Ages.

Inland ports used for civilian use

The already mentioned Dimesser place was not only most likely a military port, but also seems to have been the long-distance trading port of Gaulish-Italic merchants. This is indicated by a high density of transport amphorae of Mediterranean origin as well as other imported finds from Gaul and the Mediterranean area. The structural finds such as stone paving (possibly a loading ramp for flat-bottomed ships ) and quays support this assumption. In connection with the trading activities, a prosperous civil settlement has also emerged at Dimesser Ort, which must have been the civil center of Mogontiacum as early as the middle of the 1st century.

Other civilian ports or landing sites with less complex quays and freight houses were also found up the Rhine near the old town of Mainz (Dagobertstrasse, Kappelhof, here the discovery of two Roman embankments from the 1st century). The Celto-Romanesque native Rhine boatmen and traders are likely to have worked here, the existence of which is well documented, for example, by the tombstone of the shipowner and trader Blussus (dated around 50). Roman raft shipping was also of great importance and should have come first, especially when it comes to transporting timber on the Rhine to Mogontiacum.

Stage theater

A stage theater in Mogontiacum is documented as early as 39 by the writer Suetonius . The remains of the theater, which are visible and uncovered today, date from the 2nd century and probably followed an earlier theater built using wood and earth technology. With a stage length of 41.25 m and a diameter of the audience of 116.25 m, it is the largest Roman stage theater north of the Alps. It could thus offer space for over 10,000 spectators. The stage theater, which was located in the direct vicinity of the Drususstein south of the legionary camp, was very likely used in addition to the regular theater business also in connection with ritual celebrations for Drusus, which could explain the relatively generous expansion.

The theater was in use until the 4th century, but after the second city wall was built and the city area was reduced in size, it was outside the protected city area. Spolia from the theater sector was already used for the construction of this second city wall . The massive cast masonry vault was used as an early Christian burial place from the 6th century. Even in the early Middle Ages there were ruins of the theater visible above ground, which were mentioned in written evidence. The last remains of the theater visible above ground were leveled in the middle of the 17th century when the citadel was expanded.

Roman Rhine Bridge

Shortly after the founding of the camp under Drusus, but at the latest before his campaign from Mogontiacum in 10 BC. BC, there was probably a ship bridge (pons navalis) to the right bank of the Rhine. From the year 27 and thus in the Tiberian period , the first solid wooden bridge construction has been dendrochronologically proven. It was most likely a Pfahljoch bridge. Under Domitian, a permanent bridge was built in the early 80s, which crossed the Rhine about 30 m above today's Theodor Heuss Bridge . The 420 m long bridge had at least 21 stone pillars, 14 of which were archaeologically proven in the river bed, each of which rested on elaborately placed post gratings. The wooden bridge structure, which carried a 12 m wide multi-lane carriageway, lay on the stone pillars. A building inscription on the bridge ramp on the left bank of the Rhine comes from the Legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix , which was stationed in Mogontiacum from 70 to 92. The Rhine bridge was renewed and repaired several times, for example in the years 100, 157, 213 and in the following decades. It is assumed that it was still or again in function at the beginning of the 5th century and that the Rhine crossing of the Germanic invasion took place via it in 406. A schematic illustration of the pile grid bridge can be found on the Lyon lead medallion from around 300.

Due to the different pillar spacing, the bridge had a uniformly curved carriageway, so that the greatest possible clearance for Rhine ships was available in the middle of the river. On the right bank of the Rhine, the bridge carriageway led directly into the Castellum Mattiacorum , so the bridge was also militarily secured.

There is also evidence of a smaller bridge over the Main, which was slightly above the mouth of the Main. Possibly there was also a second Rhine crossing in the form of a ship bridge or a permanent ferry crossing. This could have been below the auxiliary camp in Mainz-Weisenau, but has not yet been clearly proven in research.

aqueduct

To supply the legionary camp on the Kästrich and later also the civil settlement, an elaborate aqueduct was built as early as the 1st century, partly in an aqueduct construction. The water supply to the camp via wells in the inner storage area failed due to the groundwater level at a depth of over 20 m. The water transport for the camp, which was initially occupied by at least two legions, from the neighboring Zahlbachtal was also not possible in the long term.

That is why there was probably a wooden aqueduct as early as the first half of the 1st century, which supplied the camp with fresh water. As the starting point of this aqueduct, the areas of today's Mainz districts Drais and especially Finthen with numerous springs could be localized. So far, however, there is no reliable evidence of a wooden previous building.

As part of the large-scale construction work of the Flavian emperors, a stone-built aqueduct was built, probably at the same time as the expansion of the legionary camp in Stein. The Mainz Legions Legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix and Legio I Adiutrix were involved in the construction , as brick stamps show, which allow a relatively precise chronological order of this construction project. The aqueduct led from the sources in Finthen first underground, later in a flow channel to the head station at the southwest corner of the camp. The aqueduct was almost nine kilometers long. For the last three kilometers it was built using an aqueduct construction and crossed the Zahlbach Valley on arches over 25 m high, probably two-story. The center distance was around 8.50 m, the average gradient over the entire line was 0.9%. Calculations resulted in a daily amount of water of several 100 m³ fresh water, which was distributed via lead pressure water pipes in the camp and also in the canabae .

In the Zahlbach Valley, the massive cast wall cores of the pillars can still be seen over a distance of around 600 m. The pillar stumps, known as “Roman stones”, still rise several meters in some cases, but are almost completely deprived of their former casing.

City wall and city gate

Shortly after the middle of the 3rd century (the section of the wall running parallel to the Rhine could be dated to the period 251/253 by examining wooden post gratings) the civil settlement between the legionary camp and the Rhine was surrounded for the first time with a city wall. The city wall connected to the fortifications of the legionary camp to the southwest over a length of 600 m, but it remained independent. It had rectangular, slightly protruding towers and a moat. The canabae legionis to the southwest in front of the legionary camp were also fortified, while the civilian settlements at Dimesser Ort and in Weisenau were outside the fortified urban area and thus further lost their importance. At the same time the stone wall of the legionary camp was renewed, meanwhile for the third time since the construction of the first stone camp wall under the Flavian emperor.

After Julian's victory over the Alamanni in 357, the construction of a second, shortened city wall began in the period 360–370, probably starting under his rule. At the same time, the legionary camp was abandoned after more than 350 years and the resulting gap in the fortifications was closed by a newly built section of wall in this area. For this purpose, spoils from the demolished large buildings of the legionary camp were used, which were processed here in large numbers. The demolition of this section of the wall in the period from 1899 to 1911 accordingly led to a large number of high-quality architectural parts, which, among other things, allowed a reasonably safe reconstruction of the praetorium and other large buildings of the legionary camp and the Dativius-Victor arch. With the construction of the second city wall, an urban area of 98.5 hectares was now enclosed, about a third of the previous urban area.

In the course of construction work on the Kästrich, the remains of this second city wall as well as a Roman city gate and the paving of the road through it were discovered in 1985. The city gate was integrated into the 2.70 m wide city wall and the via praetoria , which still came from the legionary camp, was passed through, which led down to the civil settlement as a strategically important road. Ground lanes on the door sill and the well-preserved sandstone pavement are 1.90 m wide and have the typical track width of Roman vehicles. The city gate was closed with a double-leaf wooden gate and also had a gate tower. The entire gate system is thus to be assigned to the "Andernach" type and is one of the latest gate systems known and preserved in Roman Germany.

Monuments

The only and most important monument from the time of Mogontiacum still standing at the original location is the so-called Drususstein . In science it is now, after interim doubts and classifications in later periods, more or less proven that this is probably the cenotaph (tumulus honorarius) of the Roman general Drusus. This was made by the Roman army in honor of 9 BC. Chr. In Germania fatally injured general in Mogontiacum. The monument was later approved by Augustus, who gave it a specially written grave poem. Even Roman historian such as Suetonius or Eutropius mention explicitly the Drususstein and the cult ceremony to commemorate Drusus.

The monument also became the focus of annual cult and commemoration celebrations (supplicatio) in honor of Drusus, to which members of the parliament of the three Gaulish provinces (concilium Galliarum) traveled. The Roman legions from Mogontiacum honored their former military leader with parades (decursio militum) . The nearby theater with its more than 10,000 seats is likely to have been included in these celebrations.

The remains of the cenotaph, which are still visible today, are an almost 20 m high stone building made of solid cast masonry with built-in stone. The original height should have been 30 m (this corresponds to 100 Roman feet). Reconstructions are based on a square base and a cylindrical projectile (tambour) on which a cone-shaped attachment sat, crowned by a pine cone . Similar grave structures from the early imperial era can also be found on Roman grave roads in Italy.

The Great Mainz Jupiter Column is a monument erected in Mogontiacum in the second half of the 1st century in honor of the Roman god Jupiter. It is not only considered the earliest datable monument of its kind, but also the largest and most elaborate Jupiter column in the German-speaking area. The Mainz Jupiter Column was the model for subsequent Jupiter (gigantic) columns, which were mainly erected in the Germanic provinces in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The 9.14 m high, richly sculpted column crowned a 3.36 m high Jupiter figure including an eagle made of gilded bronze. The founder's inscription is related to a declaration of loyalty to Emperor Nero and identifies the canabarii , in this case the residents of the civil settlement Dimesser Ort on the banks of the Rhine, as the donor. The column, made up of over 2000 individual fragments, is now in the Landesmuseum Mainz, only a few remains of the bronze figure have survived. A true-to-original replica of the Great Mainz Jupiter Column stands today in front of the Rhineland-Palatinate state parliament in Mainz.

Another important monument from the middle of the 3rd century is the Dativius Victor Arch . In the Roman Mogontiacum, this arch served as the central passage of a portico of a public building, possibly near the legionary camp. A large part of the arch (43 of a total of 75 individual sandstone blocks) was discovered as spolia between 1898 and 1911 when the medieval city wall was laid down in the lower, late Roman area of the foundation. This arch is also provided with lavish relief decorations, including a partially preserved zodiac , vine tendrils and Jupiter / Juno. The completely preserved inscription names Dativius Victor, decurio of the civitas Taunensium (councilor of the Taunenser regional authority in Nida) as the founder. He settled down in Mogontiacum possibly as a result of the increasing unrest caused by the Alemanni incursions that began in 233 and donated the arch out of gratitude. The original, like the Jupiter Column in Mainz, is in the stone hall of the Landesmuseum Mainz, while a replica is in the immediate vicinity of the Electoral Palace and the Roman-Germanic Central Museum located in it.

In 1986 the foundations of a large three-sided building were found in Mainz-Kastel, which may have been an arch of honor. These are possibly the remains of the arch of honor for Germanicus , the son of Drusus, mentioned in Tacitus and in the Tabula Hebana . Mention is made of the erection of three arches of honor for Germanicus after his death in 19. One of them stood in Mogontiacum apud ripam Rheni . The time and personnel allocation of the found foundations is, however, controversial. The presumed arch of honor could also have been erected by Domitian during his Chat Wars.

Sanctuaries and places of worship

Mogontiacum was the center of religious and cultic life in the surrounding area. In Mogontiacum, due to the character of the city, this was clearly militarily shaped. The imperial cult played a major and central role in the area around the Drususstein, beginning with the cult and commemorative celebrations in honor of Drusus and his son Germanicus in the early days of Mogontiacum. Later, the religious and cultic life corresponding to a provincial capital developed, which also radiated into the surrounding area. On the part of the Celtic-Romanesque population, the worship of native, and relatively quickly Romanized, Celtic deities flowed into it.

Nine cult sites from Mainz and the surrounding area have so far been archaeologically developed or can be assumed based on archaeological evidence. Another nine places of worship are only documented epigraphically. Instead, Mogontiacum has the largest number of consecrated monuments in the Gallic and Germanic provinces, including 272 dedicatory inscriptions. Most of these, however, come as spolia finds from the base of the late antique medieval city wall and thus do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the geographical location of the sanctuaries. Cults of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva and perhaps also Apollo were possibly in the area of today's cathedral district, but there is no direct archaeological evidence for this. Whether Mogontiacum, like Trier or Cologne, was a sanctuary of the “Capitoline Triassic” is questionable due to the lack of an official city character. Numerous consecration stones exclusively from legionary legacies point to a sanctuary of Apollo and another unknown deity in the immediate vicinity of the Rhine bridge, which can be attributed to the military. A sanctuary of Bellona in Castellum and a Sacellum of Mercury between Mainz and Mainz-Hechtsheim are epigraphically secured . Sanctuaries of the Genius Loci , Bonus Eventus or the Fortuna Conservatrix are also only accessible epigraphically, but cannot be localized .

A more precise localization is possible at other sanctuaries and places of worship. As early as 1976, a mithraium was excavated at the ball court and thus at the foot of the Kästrich with its legionary camp , but it was destroyed in the course of further construction work. What is unusual here is the very early veneration of Mithras, which could be dated to the period between 70 and 80 and thus to the Flavian period through ceramic finds. With a total length of 30 m, it is the oldest and largest recorded mithraium of the Roman Empire. The time of origin, size and furnishings suggest that the sanctuary is held in high esteem and its great role in spreading the cult in the two Germanic provinces.

The joint cult complex of Isis and Mater Magna found in 1999 , however, was excavated under archaeological supervision, conserved and, together with some of the rich finds from religious and cultic life, prepared for museum visitors. As with the mithraeum, the early dating of the sanctuary to the Flavian period, more precisely to the time of Vespasian, is surprising. Until it was discovered, it was not known that the cult of Isis had penetrated the northern provinces of the Roman Empire so early. Scientists assume the massive military presence in Mogontiacum as the reason for the early establishment of this oriental cult (as well as the Mithras cult mentioned above).

The diverse individual finds provide detailed information about the officially practiced cult practices in honor of Isis and Mater Magna in Mogontiacum. Other outstanding epigraphic testimonies are found in greater numbers leaden curse tablets give that magical ritual along with the discovered magic dolls a glimpse of the forbidden by Roman law and illegally practiced cult world of simple provincial Romans.

The sanctuaries of Mercury and Rosmerta in Finthen and of Mars Leucetius and Nemetona in Klein-Winternheim are not located directly in Mogontiacum, but clearly have a closer relationship to the settlement and military camp . It is assumed that the first pair of gods had a larger common temple based on the Gallic model around the year 100. The life-size bronze head of a goddess found in 1844 , which is generally referred to as a portrait of the Celtic goddess Rosmerta, also comes from there . This was often worshiped in cult community with the Roman god Mercury or his Celtic pedant. The high quality made bronze dates to the beginning of the 2nd century and shows clear influences of the Roman style, but was probably made on site in Mainz.

The smaller sanctuary of Mars Leucetius and Nemetona was located further outside of the core settlement area and, like the Mercury / Rosmerta sanctuary, probably goes back to an Aresak sanctuary from pre-Roman times. A bronze votive plaque by Senator Fabricius Veiento and his wife for Nemetona from the Flavian period shows that the Celtic goddess was also worshiped in the Flavian period.

Trade and craft

The economic importance of Mogontiacum as a trading center and production facility increased rapidly after the legion camp was founded. Finds from the camp canabae and the civil vici suggest a steadily growing economic prosperity , especially from the Flavian period to the abandonment of the Limes.

Considering the number of stationed soldiers of up to four legions including auxiliary troops, it can be assumed that Mogontiacum quickly became an important center for local and long-distance trade. In local traffic, the location on the Middle Rhine and inland shipping may have also played an important role, as demonstrated by the finds of barges and transport barges or the tomb of the wealthy Romanesque-Celtic inland shipper Blussus in Mainz. The civilian settlements that flourished as a result, in particular the civilian settlement at "Dimesser Ort" with its Gallic-Italian long-distance trade merchants, profited from trade and from the handling of goods via Rhine shipping.

Trade flows from the surrounding country now also converged in Mogontiacum. Well-developed roads led from Mogontiacum in the direction of Cologne, Trier, Worms and beyond via Alzey to Gaul. With the construction of the permanent bridge over the Rhine at the time of the Flavians, trade and the exchange of goods with settlement areas on the right bank of the Rhine increased significantly. With the increasing settlement of military veterans in the urban area or in the surrounding area of Mogontiacum ( villae rusticae have been found in all Mainz suburbs), the number of craft and agricultural businesses to supply the military and the civilian population also increased. In the individual vici of Mogontiacum, entire artisan quarters emerged, for example a significant collection of shoemaker's shops along the camp road down to the Rhine in the area of today's Emmeransstraße. There were also pottery shops (for example in the area of today's government district), metal workshops or bone and leather processing companies at the northern end of the settlement area, as well as weapons workshops for the soldiers stationed in Mogontiacum.

In the civil settlement near Weisenau, inland shipping, which was in the hands of the Celtic population, flourished in the first decades after the establishment of the legionary camp. This was then increasingly displaced by a larger number of pottery businesses or by a real "pottery industry" from the Flavian period, which from then on became the main source of income for the civil population there. There was also a Roman lamp factory, dated between the years 20 and 69, which was possibly a military operation.

Thermal baths and fort baths

A larger thermal bath building was built in the year 33 in the immediate vicinity of today's State Theater and thus at the fork of the main road coming from the legionary camp. Due to the silty subsoil at the time , the building was placed on a pile foundation, the remains of which enabled exact dating. The thermal baths must have been one of the first large stone buildings in the otherwise sparsely populated inner city area. It was destroyed as early as the second third of the 1st century, possibly in connection with the destruction of civil facilities in Mogontiacum during the Batavian War. A successor building was possibly a bit offset and more central to the inner-city center that emerged from the Flavian period on today's flax market. During construction work in the 1980s, massive remains of a larger building complex from the late 1st century were found 200 m away in Hinteren Christofsgasse. Larger amounts of stamped hypocaust bricks and parts of a marble fountain could possibly speak for a thermal bath building.

The fort bath belonging to the legionary camp was the only larger building complex of the camp that could be excavated and mapped in 1908. The fort bath was relatively large at 69 × 50 m and was probably only built after the year 90 after the second legion stationed in Mogontiacum had left. On the basis of the structural remains, two construction phases could be determined: an older and smaller bathing complex with a circular study from the late Flavian or early Trajanian period and a larger, completely rebuilt second bathing complex from the early Hadrian period. This bath was in use until the camp was abandoned in the middle of the 4th century, as evidenced by a stamp of the 22nd Legion with the addition CV for Constantiniana Victrix . The Legion only had this name affix since Constantinian times.

Burial grounds

In Mogontiacum there were numerous grave fields that arched around the settlement area. They originated in the 1st century and were used continuously until the 4th century, in some cases until the early Middle Ages. The starting points for the burial fields that were created were usually the traffic routes from the legionary camp. In addition to the numerous smaller grave fields around Mogontiacum, two larger burial sites can be made out, in Oberstadt / Weisenau and in Bretzenheim on the slope of the Zahlbach valley below the camp. Most of the tombstones found in Mainz so far come from these two burial grounds.

There was an Italian-Roman grave road (via sepulcrum) along the connecting road between the legion camp and the military camp or the vicus in Weisenau. References to Roman tombs have been documented there since the end of the 18th century. After an initial investigation by Ernst Neeb in 1912, the grave sites there were only systematically researched between 1982 and 1992. Beginning with the starting point of the road at the legionary camp and in the vicinity of the Drusus cenotaph, burials along the road have already been proven for the Augustan period. One of the first grave monuments in the immediate vicinity of the camp, which was created at the same time as the Drusus cenotaph, is the high quality grave monument of the brothers Marcus and Caius Cassius, originally from Milan, members of Legio XIIII Gemina, which is known as the "Cassier Monument". In the direction of Weisenau, more and more grave monuments and grave enclosures were built over a length of 2.5 km to the left and right of the road and separated from it by a ditch until well into the 4th century. Due to the representative character along the important military road and the initial proximity to the Drusus cenotaph, this burial site was apparently preferred by members of the military as well as by local Roman citizens and the wealthy Roman upper class. The military and civil burials were carried out partly according to Italian custom and partly according to local customs. From the 2nd century on, the prestigious importance of the grave road slowly declined, stone buildings were partially removed and their material was reused to build new graves. For the construction of the city wall in the 3rd and 4th centuries, grave monuments were removed as building material and built in in the form of spoilage. Other burial grounds, especially in the northern settlement area, now increased in importance.

A large Augustan military cemetery was located on the western slope of the Zahlbach Valley and thus below the legionary camp. There were numerous military burials here in the 1st century. Most of the military gravestones found in Mainz, often qualitatively and epigraphically valuable, come from this burial ground. In the course of the 1st century, the burial ground expanded further south across the plateau. Towards the end of the 1st century the number of military burials decreased drastically and shifted southwards near the theater. The burial ground was now increasingly used by the civilian population of the increasingly important camp canabae, in the direction of which it expanded during the 2nd and 3rd centuries. A burial tradition could be established well into the 4th century. The abandonment of this burial place is certainly directly related to the abandonment of the legionary camp and the camp canabae around the middle of the 4th century.

Numerous other smaller grave fields existed, for example, in today's Neustadt am Dimesser Ort or in the garden field, on the grounds of the Mainz main cemetery and Johannes Gutenberg University and in almost all other Mainz suburbs. In some of the grave fields, coemeterial churches were built in late Roman times , which went hand in hand with the increased number of Christian burials until the Frankish period.

Large buildings that cannot be located

In contrast to other larger Roman cities such as Trier or Cologne, the topography of Mogontiacum still has larger gaps. So it is not surprising that the location of some larger administrative and civil buildings and squares is still unknown. The governor's palace, built after the establishment of the province of Germania superior from the mid-80s of the 1st century, is one of the large-scale buildings that have not yet been localized. Several possible locations have so far been considered and discussed in specialist circles. Since the legionary camp was only occupied by one legion after the withdrawal of the Legio XXI Rapax in 90 and offered enough space, the construction of a governor's palace and other administrative buildings in the interior of the legionary camp are being considered. A graffito on a pottery shard from the 2nd century gives the governor's address “… praetorium… ad hiberna leg XXII PPF” and is an indication of this hypothesis. Recently, however, there has been a tendency again to look for the location of the governor's palace outside the legionary camp, despite this inscription. Larger remains of the building with stamped bricks and marble furnishings in the old town in the area of Hinteren Christofsgasse / Birnbaumgasse could be the remains of the governor's palace, which, similar to its Cologne counterpart, could have stood above the banks of the Rhine and raised above it. The proximity to the center of the “flax market” of the growing together civil settlement would have been given. Future planned excavations in the area of Birnbaumgasse should contribute to further clarification. Another possible location would have been the area near today's State Theater , which was also considered a central place in the area of the civil settlement.

According to some scientists, the Mogontiacum forum is most likely to be in the area of today's Schillerplatz . The central and flood-free location in the immediate vicinity of the legionary camp is an indication of this location. At the same time, Schillerplatz is the center of numerous Roman streets that converged here, giving the square a certain centrality in terms of traffic. Other possible locations are, similar to the Governor's Palace, the Flachsmarkt areas and the urban area on which the Mainz State Theater complex and its annexes are located today.

In addition to the Roman stage theater , there was almost certainly an amphitheater in Mogontiacum . Dedications from gladiators found on site are to be regarded as an indication of existence. There are only vague references to the location. One possible location would be the Zahlbach Valley near the Dalheim Monastery, which no longer exists, and the proximity to the legionary camp would also speak for it. In the records of the Mainz monk Siegehard around 1100, there is talk of the ruins of a theater in the Zahlbachtal, which is said to have been built for gladiatorial and circus games. In his Old History of Mainz (in several volumes, published from 1771), however, Father Joseph Fuchs located the Mainz amphitheater at a different location, namely between today's city center and Hechtsheimer Berg . There is a large semicircle on the bottom of which remains of strong pillars have been found.

The temple district for the state deities Jupiter, Juno and Minerva (Capitoline Triassic) is also unknown. Due to the location of dedicatory inscriptions, the cathedral district is most likely to come into question here; However, this hypothesis is not archaeologically tangible.

At the gates of Mogontiacum

In the immediate vicinity of Mogontiacum, in addition to the civilian settlements in Weisenau and Bretzenheim, numerous villae rusticae emerged over time. This has been proven for example in Gonsenheim , Laubenheim , between the Lerchenberg and Ober-Olm and in almost all other Mainz suburbs. They increasingly ensured the supply of Mogontiacum with food and other agricultural goods, with which the civil settlement gradually assumed the central market function for the surrounding area. In the Gonsbachtal, which belongs to the Mainz suburb of Gonsenheim, surprisingly larger ruin complexes and the high-quality relief of a tied Germanic were found during renaturation measures at the end of 2013 . The size and structural quality of the Roman remains suggest military use. A larger circular structure with a diameter of 40 m resembles an oval track or a lunging area in today's equestrian sport, so that it may have been a facility for Roman cavalrymen and their training - also considering the stream location and meadow meadows that are favorable for animal husbandry . In the meantime, the responsible archaeologist at the Mainz Archeology Directorate , Marion Witteyer , has indeed identified the facility as a stud from late antiquity, possibly operated by the military stationed in Mogontiacum.

The closest larger settlements on the left bank of the Rhine were Bingium ( Bingen ), Altiaia ( Alzey ) and above all the Civitas Vangionum / Borbetomagus ( Worms ). Other larger cities such as Augusta Treverorum ( Trier ) or the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium ( Cologne ) were also quickly accessible via well-developed roads such as the Roman predecessor of today's Hunsrückhöhenstraße or the Rheintalstraße . On the right bank of the Rhine, Aquae Mattiacorum ( Wiesbaden ) was founded as the closest neighboring town in the late 1st century . The hot springs there were highly valued by the Romans and remained in Roman hands until the middle of the 4th century.

Significant individual finds

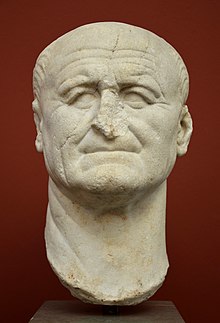

Over the centuries, many finds from the time of the ancient Mogontiacum were certainly made in Mainz. In the early and high Middle Ages there are hardly any records of this in historiography, this changed at the latest with the Renaissance and the following Age of Enlightenment . At that time, significant individual finds were mainly stone finds such as gravestones or monuments. There was a significant increase in individual finds, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when intensive building activity began in the city and older structures such as the Roman-medieval city wall were finally demolished. Other small finds were made again and again in the Rhine , such as the " Sword of Tiberius " in 1848 . This is a very well-preserved gladius with ornate brass fittings on the scabbard . These show high quality motifs from the official political and propagandistic image program of Tiberius' Germanic politics . Both have been in the British Museum in London since the 19th century , a copy of which is in the Roman-Germanic Central Museum. In the second half of the 20th century a number of individual finds were made, which today are among the most important pieces of Mogontiacum's Roman past. In 1962, the year of the supposed 2000th anniversary of the city of Mainz, a marble head was found that dates from the early 1st century. The person depicted is attributed to the Julian-Claudian imperial family and was worked in an Italian workshop. In Mainz there has not yet been a qualitatively comparable counterpart. Since the find was rather accidentally made without any direct connection to the find, the authenticity of the piece was initially doubted. In the meantime, however, the dating of the marble head has been secured through detailed investigations.

In 1981 a total of nine different ship remains from the early and late Roman times were found in a construction pit near the Rhine. The Mainz Roman ships were the more or less well-preserved remains of a total of five military ships of two different types ( Navis lusoria ) as well as civilian cargo ships such as a barge. The special importance of the finds not only entailed an extensive restoration, but also led to the establishment of a separate research focus “Ancient Shipping” in Mainz and the establishment of a dedicated museum.

In 1999, the structural remains of an Isis and Mater Magna sanctuary from the 1st century were surprisingly found. The finds made in the process give a detailed insight into the cultic-religious everyday life of the provincial Roman population of Mogontiacum. Of particular importance are the 34 different escape signs found here , which almost doubled the number of escape signs known in Germany.

Christianity in Mogontiacum

It is not clear when Christianity first took hold in Mogontiacum. The current state of research is that there is no definitive evidence of Christianity, however organized, or of Christian martyrs in Mogontiacum for the time before the change of Constantine . Even after the Constantinian turning point in the religious policy of the Roman Empire, an organized church congregation was only slowly built up. Due to the city's centuries-long status as a central military base, other religious cults such as the imperial cult and other cults popular with the military, such as the veneration of Mithras , continued to dominate for a long time . Compared to other, less military cities like Trier or Cologne, this delayed the establishment of a Christian community in Mogontiacum.

The first reliable reference to a larger Christian community in Mogontiacum dates back to the year 368. Ammianus Marcellinus reported in connection with the invasion of the Alamanni under Rando of a large number of Christians who gathered for a church festival and were partly kidnapped by the Alamanni . Ammianus expressly emphasizes that there were men and women of all classes among the prisoners, which suggests a long-established Christian community with believers from higher social classes. A second reference to a large ecclesiastical community in Mogontiacum is provided by the late antique church father and theologian Hieronymus in a letter written around 409 to the Galloroman Ageruchia:

" Mogontiacus, once a famous city, was conquered and lies destroyed, many thousands were slaughtered in the church ... "

Hieronymus refers here to the destruction of Mogontiacum (incorrectly spelled Mogontiacus ) in the context of the crossing of the Rhine by Germanic multitudes 406/407 there. The martyrdom of Saint Alban of Mainz , which he suffered in Mogontiacum, is also associated with this event . Two other Christian martyrs are possibly attributed to Huns invasions around 436 in connection with the annihilation of the Burgundian empire on the Rhine, or later Hunnic soldiers during the western campaign of Attila in 451. It is said to have come to the martyrdom of the Bishop of Mogontiacum Aureus and his sister Justina.

Bishops of Roman times

In the older literature, a Mar (t) inus is mentioned as the first bishop of Mogontiacum known by name. Proof of this is the signature of a Martinus episcopus Mogontiacensium at a Cologne synod on May 12, 346, at which 14 Gallic and Germanic bishops met to depose and excommunicate the Cologne bishop Euphrates . Meanwhile, the majority of the opinion is that the acts of this Synod go back to a forgery, probably from the 10th century, and that this Synod did not exist, at least with this aim. A bishop Mar (t) inus is also historically not fixable there outside of his mention.

This also applies to a number of other bishop names from Roman times, which are mentioned in eight different versions of medieval bishops' lists. Starting with a Crescentius in the 1st century, who was considered to be a pupil of Paulus of Tarsus , a different number of bishops up to the middle of the 6th century historically tangible Sidonius is mentioned. Only aureus is considered to be relatively certain for the middle of the 5th century. It is possible that there were already Roman bishops with the names Marinus, Theomastus / Theonest , Sophronius / Suffronius or Maximus before that , but they are historically not unambiguous, but at best indirectly accessible. An indication of the earlier existence of Roman bishops in Mogontiacum is the reference in the greeting from the church teacher Hilary of Poitiers from the year 358/359. He dedicates this to the “beloved and blessed brothers and co-bishops of the provinces Germania prima and Germania secunda ”.

Roman church foundations

The location of an official Roman episcopal church and the time it was built are still unclear and are discussed controversially in professional circles. It is relatively certain that this church could not have been under today's cathedral grounds. Under the nearby Evangelical Church of St. Johannis , excavations in 1950/51 (and 2013 to 2017) revealed the foundations of a larger late Roman building. Since then, these have often been interpreted as the remains of the first episcopal church, which one has to imagine as a church family with a cathedral. The period after 350 and before 368 (mention of a larger Christian community by Ammianus Marcellinus) is now regarded as a possible time of origin for a bishop's church or at least a larger church.

The only late Roman sacred building in Mogontiacum that was archaeologically clearly documented in 1907/10 was the Basilica of St. Alban . This Coemeterialkirche in the area of the southern burial ground was built in the first half of the 5th century using high quality Roman wall technology. The patronage of Alban of Mainz speaks for a dating to the time shortly after the Germanic invasion in 406/407 . His martyrdom probably took place in connection with the devastation of the city. It is possible that there was a previous building as early as Roman times, which Christian tombstones from the late 4th century could indicate on site. The single-nave apsideless basilica was built over the tomb of St. Albans and measured 15 × 30 m.

The emergence of further coemeterial churches in the late 4th and early 5th centuries can only be indirectly assigned to the Roman period, but is considered likely. The chapel and later church of St. Hilary was the burial church of the Mainz bishops until the 8th century, which speaks for its early importance. It originated in the Zahlbach Valley, since the early 1st century a burial place mainly for the military and in early Christian tradition the vallis sacra of Mogontiacum. Further to the north, St. Theomast (eponymous for the Dimesser town ), St. Clemens and St. Peter ( St. Peter ex muros or Old St. Peter ) can also be assumed to have originated in the late Roman period. In the case of the latter church, this is considered relatively certain due to the continuity of tombstones with Roman and Germanic names.

Research history of Mogontiacum

Research into the Roman Mogontiacum began in the electoral Mainz in the Renaissance era and under the influence of humanism . Scientists, scholars but also clergy, military and civil engineers from the environment of the electoral court or the University of Mainz were repeatedly involved. A pioneer in research into Mogontiacum was Dietrich Gresemund , Doctor of Both Rights and Canon of St. Stephen . He collected Roman inscriptions and wrote a treatise on his collection as early as 1511, which was lost after his sudden death in 1512. Immediately after him, Johannes Huttich published his work Collectana antiquitatum in urbe atque agro Moguntino repertarum in 1520 with the support of Elector Albrecht von Brandenburg . Other explorers of Roman history were the Mainz cathedral vicar Georg Helwich, whose work Antiquitates Moguntiacenses was lost as well as writings by Heinrich Engels, dean of the St. Peter monastery, or by Johann Kraft Hiegell , an electoral Mainz military medicus. The commander of Mainz fortress , Johann Freiherr von Thüngen , also joined the group of collectors of Roman monuments and book authors. Due to the intensive construction activity in Mainz after the Thirty Years War , especially during the expansion of the Mainz fortress, many Roman stone monuments were found, which Thüngen was able to examine and describe first hand. This work has also not survived.