Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes

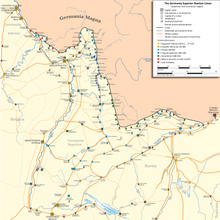

The Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes ( DIRL ) was a large-scale defense and border surveillance system of the Roman Empire , which was created after the abandonment of the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes in the late 3rd century AD ( Limesfall ). In a narrower sense, the term only describes the fortifications between Lake Constance ( Lacus Brigantinus ) and the Danube ( Danubius ); in a broader sense also the other late Roman fortifications on the Upper Rhine (Constance to Basel) and Upper Rhine (Basel to Bingen) ( Rhenus ) and on the Upper Danube.

Location and function

The especially Alemannic raids around the middle of the 3rd century AD made a newly designed military security of the north-western imperial borders of Rome necessary. The Upper German-Raetian Limes was never intended as a military defensive system and was therefore abandoned after 260 (so-called Limesfall ). The border troops were again withdrawn to positions behind the easier-to-control rivers Rhine ( Rhenus ), Danube ( Danuvius ) and Iller ( Hilaria ). The systematic expansion of the new military border began around 290.

The defenses there, as the large number of small fortresses shows, did not serve to ward off major attacks, but were intended to ensure almost complete surveillance of the Limes and deter looters. Until 378, the Romans repeatedly penetrated the Germanic settlement areas on the other side of the Limes (such as under the emperors Julian Apostata or Gratian ) in order to punish and intimidate the tribes living there and thus prevent new attacks on the empire. The late Roman border defense was based on the one hand on the fortress belt of the Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes, on the other hand on offensive operations and preventive strikes in the tribal areas as well as on alliances with the Germanic princes. When the punitive expeditions had to be stopped due to the rapid deterioration of the military and administrative structures of West Rome, this led to a massive worsening of the security situation.

Castles

The question of whether the fortress construction program can already be ascribed to the emperor Probus (276–282) as the initiator, who is praised by an inscription in Augsburg as restitutor provinciarum et operum publicorum (which, however, does not have to be related to the Limes), or what is much more likely - a little later Diocletian (284–305) and his fellow emperors. The beginning of the coin series in the forts and various building inscriptions speak for the latter. For example, the Eschenz ( Tasgetium ) fort , which later formed the settlement core of the town of Stein am Rhein , was founded or expanded between 293 and 305, according to an inscription. In addition to the revival of the legionary camp in Vindonissa ( Windisch ) around 265, several forts were built along the Danube, the Iller , the High Rhine and Lake Constance from around 285 ; so among others in Basilia ( Basel ), Augusta Raurica ( Kaiseraugst ), Tenedo ( Bad Zurzach ), Constantia ( Konstanz ), Arbor Felix ( Arbon ), Brigantium ( Bregenz ), Caelius Mons ( Kellmünz an der Iller ) and Gundremmingen ( Bürgle ) .

Diocletian and after him Constantine (306–337) had the Limes equipped with massive fortresses of the latest design. The forts in Zurzach, Kaiseraugst and Arbon as well as fortifications in strategically important places in the hinterland such as Altenburg, Olten, Solothurn, Zurich - Lindenhof ( Fort Zurich / Turicum ), Irgenhausen and Yverdon point to the new strategy in border security. Fortresses such as in Alzey or Horbourg primarily served the needs of the new mobile field armies ( Comitatenses ). The strengths of the units of the stationary border troops ( Limitanei ) stationed in the other fortresses were numerically small because, conversely, the number of fortifications had increased significantly.

Some Rhine forts also secured the north bank of the river with fortified bridgeheads. Some of them, like the Ländeburgus near Ladenburg , could only be reached by ship. These watchtowers were placed within sight between the forts, they were used for border surveillance and to quickly alert the fort crews in the event of an attack. The late antique Roman fortresses usually had a completely different appearance than the forts that had secured the Dekumatenland up to around 260 : It was now apparently less about the control of the peaceful border traffic and more about a military security of the hinterland through a chain of rather small ones , but strongly fortified bases, as they were built in the Orient at the border to the Sassanid Empire .

Many fortifications were built on defense technically low altitudes (plateau or terrain spurs) ( Castle Sasbach-Jechtingen , Castle Breisach ). Most of the time, their ground plan was also adapted to the local topography in order to be able to optimally utilize the natural obstacles to the approach. Some forts, such as those of Arbon or Pfyn , therefore have a polygonal floor plan. But there are also square structures such as the port fort in Bregenz, Stein am Rhein or Schaan . Most of the forts on the DIRL were therefore less reminiscent of the early and mid-imperial camp buildings, the construction of which mostly followed a standardized plan and served more as fenced barracks than as fortresses, but rather of medieval castles. There was also a powerful Rhine fleet , the headquarters of which may have been in Mogontiacum ( Mainz ); the most important base of the Lake Constance flotilla was Brigantium (Bregenz).

The Limes was built under Valentinian I with the help of numerous smaller forts and stone watchtowers, such as B. in Möhlin , additionally secured. In addition, inscriptions found in the area of today's Switzerland document the construction of burgi in Etzgen -Rote Waage and Koblenz-Kleiner Laufen for 371; the other towers along the High Rhine probably also date from this time. Some systems in the hinterland were also built at the end of the 4th century, such as the fortified Zihl crossing at Aegerten (approx. 369) and the Burgus von Balsthal -St. Wolfgang. The crews of this burgi had the task of monitoring the traffic. Along the rivers Rhine and Danube, especially in the Maxima Sequanorum (along the road connection Bregenz – Kempten), in the Raetia II and in Noricum Ripense, watchtowers and numerous new military installations were built. A naval port for a flotilla of guard ships was built in Bregenz. In addition to other bridgehead forts, a fortified bridgehead was also built at Castrum Rauracense on the opposite bank of the Rhine. Large storage buildings were again commissioned. The horreum, which was subsequently built into Schaan Fort , was possibly built during this time and served as a supply base. The forts Rostrum Nemaviae and Abodiacum were also equipped with storage buildings. Michael Mackensen thinks it is possible that the horreum of the remaining fort in Abusina also dates to the Valentine period and that the warehouses built in Veldidena were surrounded by a tower-reinforced wall at that time. The construction of burgi in Etzgen-Rote Waag and Koblenz-Kleiner Laufen is proven by inscriptions for the year 371. All other towers on the dense chain of defense on the Upper Rhine can probably be dated to the same year. Some of the fortifications in the hinterland also date from this period. B. the crossing on the Zihl near Aegerten (around 369), the Kloten fort or the burgus near Balsthal-St. Wolfgang.

development

3rd century

After the abandonment of the Upper German-Raetian Limes and the renewed consolidation of Roman rule on the Rhine and Danube, the borderline was moved back to the banks of these two rivers in the late 3rd century under the rule of the Probus. To the west of the Germania Magna , as in the 1st century, the Upper Rhine formed from Lake Constance to the border. In the south it ran on the Iller up to its confluence with the Danube and along this further east to Regensburg. The new border ran up the Iller between Lake Constance and the Danube and then from Bregenz to Kempten a short stretch across open country. The Limes has been secured on this section since around 290 by a chain of watchtowers and forts. The Romans made alliances with the Alemannic princes, who now occupied the abandoned land to the right of the Rhine. Emperor Diocletian also tried to prevent the constant infiltration of Germanic tribes and looters by settling individual tribal groups as Laeten or Foederati on the left bank of the Rhine. You should then primarily fend off Germanic peoples pushing forward. With this, however, a Germanization of this region, promoted by the Roman state, actually began.

4th century

With the help of the fortifications on the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes, the Roman Empire was able to continue to assert itself against the pressure of the Teutons during the 4th century. In the course of a campaign against the Brukterer Emperor Constantine I (306–337) had the Deutz bridgehead fort built across from Cologne . It was supposed to secure the Rhine bridge built around 310. Other border fortifications and road posts were also built under him: Haus Bürgel (near Monheim), Koblenz, Boppard , Junkerath, Neumagen and Bitburg are known from this period. Their occupations prevented major German invasions for several decades; They probably could not effectively prevent raids by smaller groups of looters. The attachment of manors and the creation of height and escape fortresses, such as. B. on the Katzenberg near Mayen, rather point to a persistent uncertainty. A large number of previously open vici , which were then fenced with fortifications, corroborate this assumption.

All of these measures ultimately could not stop Germanic attacks. Events in the empire were also decisive for this: When the Roman troops were weakened by a bloody civil war between Magnentius and Constantius II , the Rhine Limes broke through for 353 francs and sacked the provincial metropolis of Germania Secunda , Cologne. Caesar Julian , who was responsible for the Gallic provinces, launched a successful counterattack in 356, secured the borders, defeated a coalition of Alemannic princes in 357 and put the forts of Qualberg, Xanten, Neuss, Bonn, Andernach and Bingen back on the ready to defend. Nevertheless, the old administrative organization in the north partially dissolved, and Xanten and Nijmegen were also destroyed. Julian had to sign a contract with Frankish warriors and grant them the right to settle in the region on today's Dutch-Belgian border; in return they secured the area for the emperor.

When the situation in the Roman Empire had stabilized again for the time being, Emperor Valentinian I (364 to 375) had another comprehensive fortification program carried out around 370, which Ammianus Marcellinus mentions in his res gestae . He reports that the emperor had the existing military installations strengthened along the Rhine and partly rebuilt (Amm. Marc. 28, 2, 1f.). The archaeological evidence confirms this statement.

5th century

At the beginning of the 5th century, the fortifications at sites such as Tasgetium were renewed again. After the withdrawal of a large part of the Roman troops in the early 5th century (around 402) and the temporary collapse of the Rhine border 406/407 (see Rhine crossing from 406 and migration of the peoples ), the border areas along the High Rhine still officially belonged to the Western Roman Empire ; However, in view of the internal turmoil and the growing incapacity of the central government, they increasingly had to take care of their own security, which is likely to have massively reduced the standard of living and the number of residents of these provinces, especially since the Roman troops no longer carried out retaliatory campaigns. More and more often, gangs plundering, taking advantage of Roman weakness, crossed the imperial border. However, contrary to earlier assumptions, the year 407 did not, according to recent research results, mark the end of the Rhine Limes. Between 407 and 435, the Burgundians in particular defended the border as foederati in Roman services. Around 420 they again controlled the entire length of the Rhine together with regular Western Roman units.

The border section of the Germania Seunda does not appear in the main military source of late antiquity, the Notitia Dignitatum last updated around 425 , in contrast to Raetia . It is therefore unclear how the defense of this region was organized in the 4th and early 5th centuries. Research has found very different answers to this question. Perhaps the corresponding passage in the Notitia was lost, or the forts on the Lower Rhine were already exclusively occupied by Germanic federates around 420 . Since they were not regular troop units, they were not included in the lists of the Notitia . It is also possible that the border at that time was controlled mainly by comitatens and pseudocomitatensic units, not by limitanei . In any case, archaeological excavations have revealed that border guards under Roman command in large parts of the Germania Secunda , however organized, continued well into the 5th century, as the forts remained occupied. This is shown by findings from Dormagen, Haus Bürgel and Gellep. Settlement continuity up to the Merovingian period can be observed there. However, the allied Franks on the Lower Rhine seem to have operated increasingly independently in the general chaos after 406, which u. a. resulted in several attacks on the former imperial metropolis Trier.

Nevertheless, representatives of the central government in Ravenna were still present here. Around 420 the Comes domesticorum Castinus carried out a campaign against the Franks. The army master and temporary regent of the West, Flavius Aëtius , brought the Rhineland, which was controlled by the Franks in the meantime, under Roman control in 428 (and again in 431/32) after another crisis in the years 423-425. He forced a peace treaty on the Franks, which initially put them down, but was broken again soon after the middle of the 5th century. The Roman administrative and military structures in Germania Secunda remained more or less intact up to this point. The Roman claim to this region was upheld by the army master Aegidius until the beginning of the 460s.

After 450 the power of the imperial central government and, as a result, the Roman rule north of the Alps accelerated rapidly. This finally came to an end with the defeat of Syagrius , son of Aegidius, against the Franks in 486/87. The remnants of the Roman border troops on the Rhine seem to have joined the Franks under Clovis I and then slowly assimilated. Some of the forts survived the end of the Western Roman Empire by several decades, which is proven by the archaeological evaluation of fort cemeteries and coin finds, especially by solidi . The areas south of the Danube were still controlled from Ravenna after 476 - but now by Odoacer or the Ostrogoths. The Vita Sancti Severini by Eugippius , written around 510 , a biography of Severin von Noricum, provides insights into this period, which for the Romanized population was marked by the complete collapse of state power . The vita shows that the last units of Limitanei disbanded at that time because they no longer received any pay. From the civil settlements around the late Roman fortresses, medieval towns often emerged later.

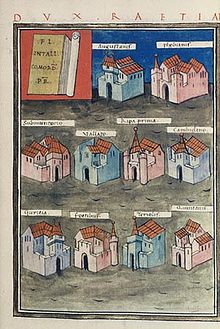

troops

Little information is available about the Roman units that guarded the late ancient Limes. Inscriptions mention, for example, the legio VIII Augusta or the unit of the Tungrecani seniores and their participation in construction work. The entry in the Notitia Dignitatum confirms that the cohors Hercula Pannoniorum were stationed in Arbon in the early 5th century . For the first half of the 4th century , the legio I Martia is known as the border troop responsible for the section of the High Rhine . The soldiers were part of the Limitanei and were under the command of Dux limites , especially of the dux Raetiae , the mobile field troops, the Comitatenses , were commanded by comites rei militaris .

The inventory of the late antique urn grave field of Friedenhain-Straubing provides clues about the identity of the border guards in the section of the Raetia Secunda . The pottery found there belongs to the Friedenhain-Prestovice group. This was mainly used by the Elbe Germans and is only found at military sites in this region. This suggests that the border troops on this part of the DIRL were largely provided by Elbe Germanic mercenaries or foederati . The recruitment of Teutons for the Roman army had a long tradition, which was particularly promoted from the 4th century. From this point on, the ethnic structure of the imperial army began to change. The old-style auxiliaries were abolished and non-Romans could join the regular army directly. This made it possible for Germanic peoples to rise to higher positions in the army from the 4th century and even to the highest imperial offices from the 5th century. Whether the total number of Teutons in the army was really higher than in the 1st to the 3rd century is a matter of dispute in research circles.

In connection with the consolidation measures around 300, according to some archaeologists, more Germanic tribes were settled in the partially depopulated Pre-Alps, while at the same time many of the new forts were manned by mercenaries who were recruited from these new settlers. The burial ground of Neuburg an der Donau was occupied by the finds from approx. 330-390 with Elbe-Germanic-Alamannic soldiers, from the last decade of the 4th century then mainly with East-Germanic-Gothic soldiers. From these grave finds it was therefore concluded that along the border of the Raetia II there were probably almost exclusively Germanic units in the forts. Something similar was also observed on the Upper and Middle Rhine and Lake Constance. It seems that wherever Alamannes settled outside of the imperial territory, Alamannic foederati were also used to guard the border on these sections of Rome . In the late 4th century, these were replaced in some sections by East Germanic units. However, it is not possible to determine the ethnic background of the units unequivocally from the material legacy alone, especially since Roman soldiers in late antiquity would have preferred the "barbaric" style of clothing and equipment ( habitus barbarus ).

The most important written source for the military history of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes is the late antique Notitia dignitatum . It was created around AD 400 and was partially updated for Westrom around 420. It also lists the units and commanding officers of the limitanei (border troops) at the DIRL along with their stationing locations. The Comitatenses , Limitanei / Ripenses and Liburnarians on this Limes section were under the command of four military leaders:

See also

literature

- Jochen Garbsch : The late Roman Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes. (Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 6), Stuttgart 1970.

- Norbert Hasler, Jörg Heiligmann, Markus Höneisen, Urs Leutzinger, Helmut Swozilek: Under the protection of mighty walls. Late Roman forts in the Lake Constance area. Published by the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg, Frauenfeld 2005, ISBN 3-9522941-1-X .

- Michael Mackensen : Raetia: late Roman fortifications and building programs. In: JD Creighton and RJA Wilson (eds.): Roman Germany. Studies in Cultural Interaction (Journal Roman Arch. Suppl. 32), Portsmouth 1999, pp. 199–244.

- Walter Drack , Rudolf Fellmann : The Romans in Switzerland , Stuttgart 1988, pp. 64–71, ISBN 3-8062-0420-9 .

- Erwin Kellner: The Germanic politics of Rome in the Bavarian part of the Raetia secunda during the 4th and 5th centuries. In: E. Zacherl (Ed.): The Romans in the Alps. Historians' conference in Salzburg, Convegno Storico di Salisburgo, 13. – 15. November 1986 , Bozen 1989, pp. 205-211, ISBN 88-7014-511-5

- Michaela Konrad, Christian Witschel : Late antique legion camps in the Rhine and Danube provinces of the Roman Empire. In: M. Konrad, C. Witschel (eds.): Roman legion camps in the Rhine and Danube provinces , Munich 2011, pp. 3–44.

- Sebastian Matz: The 'fear of barbarians' and the border security of the late Roman Empire. A comparative study on the limits on the Rhine, Iller and Danube, in Syria and Tripolitania with a catalog of sites on the late Roman Rhine-Iller-Danube-Limes , Jena 2014.

- Jördis Fuchs: Late antique military horrea on the Rhine and Danube. A study of the Roman military installations in the provinces of Maxima Sequanorum, Raetia I, Raetia II, Noricum Ripense and Valeria. , Diploma thesis, Vienna 2011.

- Valentin Homberger: A newly discovered late Roman fort near Weesen SG. Swiss Archeology Yearbook, Volume 91, 2008. PDF

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Cf. G. Kreucher: The Emperor Marcus Aurelius Probus and his time . Stuttgart 2003, p. 88.

- ↑ CIL XIII 5256. There had been a Roman fortress at the site.

- ↑ Jördis Fuchs 2011, p. 49, W. Drack 1988

- ↑ See H. Börm: Westrom. From Honorius to Justinian. Stuttgart 2013.

- ↑ See H. Fehr - P. von Rummel: Die Völkerwanderung . Stuttgart 2011, p. 85.

- ↑ Michaela KONRAD and Christian WITSCHEL (organizers): Conference report on the international colloquium “Roman legionary camps in the Rhine and Danube provinces - Nuclei of late antique and early medieval life?” Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Munich March 28-30, 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ Cf. the report in Prokopios of Caesarea , Historien 5, 12, 12-19: At that time a Roman army was also stationed in northern Gaul to defend the border. And when these soldiers had to realize that there was no way for them to return to Rome, while at the same time they were unwilling to surrender to their (Visigothic) enemies, the Arians , they stepped along with all their standards and the land , which they had long guarded for Rome, to the Teutons (ie Franks) and Arborychi. But they passed on to their children all the customs of their Roman ancestors, so that they should not be forgotten; and these people really paid a great deal of attention to them, so that they still adhere to them in my time (approx. 550 AD). To this day they are still divided according to the legions to which their ancestors were assigned in the past, they always fight in battle under their standard, and they obey Roman customs in every respect. So they preserve the uniform of the Romans in every detail, even the footwear.

- ↑ Th. Fischer: Spätzeit und Ende , in: K. Dietz et al. (Ed.): Die Römer in Bayern , Stuttgart 1995, p. 400 f.

- ↑ not. dig. occ. XXXV

- ↑ See AD Lee: War in Late Antiquity . Oxford 2007, p. 79 ff.

- ↑ See for example Sebastian Brather: Ethnic identities as constructs of early historical archeology. In: Germania 78, 2000, pp. 139–171, and Patrick J. Geary: European peoples in the early Middle Ages. To the legend of the becoming of the nations. Frankfurt / Main 2002, p. 45 ff. See also Michael Kulikowski: Rome's Gothic Wars . Cambridge 2007, p. 60 ff.

- ↑ Cf. P. von Rummel: Habitus Barbarus . Berlin / New York 2007; H. Börm: Westrom. From Honorius to Justinian . Stuttgart 2013, p. 160 ff.

- ↑ not. dig. occ. XXXV.