Sasbach-Jechtingen fort

| Sasbach-Jechtingen fort | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Sponeck |

| limes |

Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes (DIRL), Maxima Sequanorum route 1 |

| Dating (occupancy) | 370 AD to early 5th century |

| Type | Cohort fort? |

| unit | Limitanei / Foederati ? |

| size | approx. 40 × 50 m (0.5 ha) |

| Construction | Stone construction |

| State of preservation | Visible above ground, irregular structure with round and square corner towers, the east wall and two towers have been preserved. |

| place | Sasbach am Kaiserstuhl |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 6 '50.8 " N , 7 ° 35' 2" E |

| height | 202 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Legion camp Strasbourg (Argentorate) (north) |

| Subsequently | Fort Breisach am Rhein (Mons Brisiacus) (south) |

| Upstream | Horburg Castle (Argentovaria) (southwest) |

Fort Sasbach-Jechtingen is a former late Roman military camp on what is now the municipality of Sasbach am Kaiserstuhl district of Jechtingen in the district of Emmendingen , Baden-Württemberg .

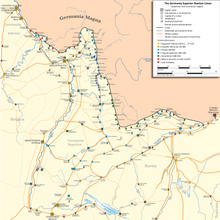

The camp was one of the numerous smaller fortifications built under Emperor Valentinian I , but only briefly occupied in the final phase of Roman rule over the Rhine provinces. It was part of the chain of castles of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes (DIRL) in the Roman province of Maxima Sequanorum . The camp was probably occupied by Roman troops from the 4th to the 5th century, who were responsible for security and surveillance tasks on this section of the Rhine border (ripa) . The fortification was occupied by the Alemanni and Franks after their withdrawal . The successor building, the medieval Sponeck Castle , was built directly over the remains of the late antique complex.

Surname

The ancient name of the fort is unknown. Conclusions about this time period can only be drawn from the current place name. The place "Uchtingen" is mentioned for the first time in 1284. The “dorf ze Üchtingen” became “Ütingen” , “Ühtingen” , “Úhtingen” , “Úchtingen” , and the name Jechtingen, which is used today, appears for the first time in the Breisgau archives around 1551. The ending -ingen refers to a personal name and is probably derived from "with the members of the Uchto" . It is possible that after the Romans left, an Alemannic tribal leader of this name had his residence on the Sponeck.

location

The fort was not - as is usual with most Limes fortifications - built on the left bank of the river, but on the right. It was strategically located on a 25-meter-high Sponeck west of the village of Sasbach, which in ancient times was still surrounded by the Rhine on its north and west side. The north-western end of the Kaiserstuhl is formed by the Humberg, which in turn ends in the Sponeck. The landscape between the rock spur and the bank of the Rhine was characterized in ancient times by dense, extensive alluvial forests and meandering river arms. Access to the rock plateau was only possible from the east and was made more difficult by a small hill. As a result of Johann Gottfried Tulla's regulation of the Rhine in the early 19th century, the river bed was shifted about 200 meters to the west. Today only a narrow oxbow river of the Rhine flows past the rock spur.

Dating

The complex was probably built around 370, during the reign of Emperor Valentinian I (364-375), in the course of the last expansion and reinforcement measures of the Rhine Limes. The Roman and Germanic finds recovered in the 1970s (Argonne sigillata, Mayen or Eifel ceramics, including terra nigra decorated with smoothing , a crest, arrowheads, six coins) came almost without exception from the second half of the 4th century AD.

function

The fortification served primarily to control the Roman road through the Zartener Basin , which crossed the Rhine here, west of Jechtingen, and was an important connecting route to the Black Forest and to the east. Along with fords near Breisach in the south and near Sasbach in the north, this heavily frequented crossing was another way of crossing the Rhine relatively safely and quickly. There was probably a bridge here at the time. From this point the crew had a good overview of the Limes road leading from Oedenburg-Altkirch / Argentovaria on the southern bank of the Rhine, the alluvial forests and also a line of sight to the nearest Roman military bases. The camp then, together with two other posts, the fort in the south near Breisach / Mons Brisiacus and the Oedenburg-Altkirch camp in what is now Alsace , secured this section of the Limes against Germanic invaders, especially against the Alemanni, who were at the time had already settled in Breisgau. The fort was thus also a fortified bridgehead in a deployment area for potential intruders and probably also served to observe the apron and the Alemannic hill settlements.

development

As archaeological finds show, the area between Hochberg and Rhine has been inhabited by people since the Neolithic Age. It cannot be ruled out that there was a Celtic settlement here until the arrival of the Romans. A road link across the river at the Sponeck had been running since early Roman times, which was of great military importance for the Romans. There was also a wood and earth fort near Sasbach in the early imperial era that was built by the Legio XXI .

In the years 259 to 260, the Alemannic tribes finally overran the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes. After that, they permanently occupied the Dekumatenland , which had been under Roman rule for more than 200 years. After the restless decades of the so-called " Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century ", the situation on the Upper Rhine, High Rhine, Lake Constance, Iller and Danube stabilized again to some extent. A new border line was created here, which from the late 3rd century onwards was secured and monitored for the next 100 years through the gradual construction of a chain of fortifications, the so-called Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes. Nevertheless, the Alamanni repeatedly break into the territory of the empire, as they were often able to benefit from the internal power struggles of the Romans, which were usually associated with an almost complete withdrawal of the border troops. The sources also report successful countermeasures and punitive expeditions by the Roman army. The starting points of such revenge campaigns were the larger cities and troop locations, which at the same time formed the backbone of the border defense:

- Strasbourg / Argentorate ,

- Colmar / Columbarium ,

- Kaiseraugst / Castrum Rauracense ,

- Constance / Constantia .

In the late 4th century a comprehensive reorganization and reinforcement of the border defense became necessary, as the Alamanni under their military leader Rando 368 even managed to plunder the provincial capital of Germania I , Mogontiacum , during a raid . This was mainly done by building and strengthening watchtowers (on the Upper Rhine), small burgi and forts under Emperor Valentinian I (364–375 AD); he was the last fortress builder on the Rhine Limes. The reconstruction of the Constantinian fort on the Münsterberg in Breisach, from where the emperor presumably personally organized the construction work on this section of the Limes in 369, and the construction of the camp on the Sponeck rock also took place during this time. The historian Ammianus Marcellinus reported in his historical work Res Gestae in detail about the construction activities on the Rhine Limes:

“Valentinian made important and beneficial plans. He had the entire line of the Rhine from the source in Raetia to the strait of the ocean (English Channel) secured by huge fortifications. He had the river [...] fortified with large dams and military camps and forts [...] built on the heights as far as the Gaulish lands extended. Sometimes fortifications were also built across the river, where it touches the land of the barbarians. "

He reports something similar in another passage:

"[...] Valentinian was rightly feared because he replenished the armies with strong replacements and fortified the Rhine on both banks of the hills with camps and forts."

Just a few years after its construction, the fort was the focus of warlike events. In 378 the Alemannic Lentiens broke through the Rhine Limes again - either directly at the Sponeck crossing or at Breisach -, devastated the border areas and tried to penetrate further into the interior of Gaul. It is possible that the fort was destroyed or damaged at that time, as a layer of fire in the NE tower suggests. The attackers were soon thrown back across the Rhine by Emperor Gratian and his Frankish generals after the battle of Argentovaria , which prevented him from getting his uncle, Valens , who ruled in the east of the empire, to help against the Goths and Alans in time who then killed him in the Battle of Adrianople . Gratian also crossed the Rhine to devastate the settlement area of the Lentiens. It was the last time a Roman army operated in the Barbaricum. The fort on the Sponeck was then quickly restored and manned again.

According to the find location within the fort and the burial ground to the northeast, the fort was occupied at least until the withdrawal of the border troops by Stilicho , 401 to 406, but probably for some time after that. Soon after the Limes dissolved, the first Alemannic new settlers from the Breisgau and Ortenau crossed the river and now also settled to the left of the Rhine. There is some evidence that the facility served as a base for the Alamanni and later also for the Franks from the middle of the 5th century at the latest. In the early Middle Ages the camp was probably abandoned and fell into disrepair. The Sponeck was only re- fortified with a hilltop castle in the late Middle Ages , and most of the fort was destroyed. The neighboring Sasbach was probably a kind of mansion with a military administrative function during the Merovingian era. According to Gerhard Fingerlin, a royal fiscus is documented for this place in the Carolingian-Ottonian period .

Research history

Roman finds on the Sponeck have been known since the early 20th century. In 1973, during a field inspection in connection with the excavations in Breisach (Münsterberg), the first traces of ancient wall remnants were discovered on the steep slope of the foreground of Sponeck Castle. In 1975 the excavations uncovered further sections of the fort wall. These were located outside the castle area and were therefore still well preserved. In May 1976 the first systematic excavations began on behalf of the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office, which were carried out by archaeologists from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. During the excavations, the remains of the south-eastern enclosing walls and parts of a central tower were uncovered. The interior could also be examined, but most of the buildings in this sector had already been completely removed in the Middle Ages by excavating the moat.

Fort

The fortress probably covered an area of about 0.5 hectares and was therefore significantly smaller than the neighboring fort in Breisach. It is therefore not to be regarded as a garrison location, but rather as a small fort or guard post. The very irregular floor plan of the complex resembled that of a medieval castle and was largely adapted to the conditions on the Sponeck plateau. Since the Roman engineers had used all the advantages of the local topography as optimally as possible, an attack was only possible from the east.

The remains of the approx. 80-meter-long eastern curtain wall, three corner towers and parts of the interior buildings could still be excavated from the fortification. The wall (foundation width two meters) and a round tower on the west side had already largely slipped down the steep slope on the Rhine side due to erosion. The extent of the fort could therefore no longer be fully determined. The eastern defensive wall was up to 1.60 meters thick and up to a height of one meter was preserved. A pile grid to stabilize the foundations was not necessary here, as they sat directly on the natural rock. In the northeast it was reinforced by a square corner tower, in the southeast by a round corner tower, the foundations of which were six to seven meters wide. At the highest point of the rock plateau a further, square tower or a kind of core structure rose like a donjon , the foundations of which could only be excavated in half. The particularly exposed southeast tower was very solidly bricked up in its lower segment. The northeast tower had a second - only from the inside - accessible room in its basement and was probably part of a gate system. Another, somewhat smaller, round tower stood directly on the south-western edge of the slope, possibly covering a small slipway leading to a mooring on the banks of the Rhine. The east side was additionally secured with a trench in front. The building material used was almost exclusively volcanic rock (so-called Essexit -Theralith) that occurs in the immediate vicinity , as well as occasional red sandstone , which was mainly used on the corner reinforcements and door sills.

Little can be said about the interior of the fort. They probably consisted of barracks with their backs butting against the curtain wall, as we know them from other late antique fortifications on the Limes (e.g. Passau , Altrip , Budapest ). Immediately behind the wall were traces of post pits and fragments of a screed floor, followed by the rubble of a collapsed and partially charred wall made of clay framework. The building floor plans could no longer be determined.

garrison

The occupation unit has remained unknown to this day. Due to its size, the fort was probably occupied by only 50 to a maximum of 100 men Limitanei / Riparenses or Germanic Foederati (allies). One of the most important ancient sources for the assignment of border troops and forts from the 4th and 5th centuries AD is the Notitia Dignitatum . However, since it does not mention the name of the fort, the occupation unit or a commanding officer, this could be a concrete indication that federation officers were actually stationed here, but they were no longer included in the troop lists as irregular units. The indication of two Auxilia Palatini units of the army in Italy:

- the Brisigavi seniores and

- the Brisigavi iuniores

In any case, in the list of troops of the Magister Peditum one can conclude that federation contracts had been concluded with the Alemannic tribe of the Brisigavi and that they possibly also provided the crews for some of the border forts. The Lentienses , another sub-tribe of the Alamanni, also settled in Breisgau , had to assign soldiers to the Roman army on the basis of such contracts. In the walls of the fort and on the northern burial ground there were indications of the presence of Alemannic mercenaries who had apparently lived here with their families (military belt buckle, pearl necklace, brooches). Nevertheless, they saw Emperor Valentinian as the greatest threat to peace on the Limes, had their senior officers removed from the army and, according to Ammianus, even referred to them as "the enemy of the entire Roman world" (hostes totius orbis Romani) . His construction work on the Upper Rhine and its apron were therefore primarily directed against them.

Finds

As with many other Roman fort sites, the coins were among the most important finds. After evaluating the spectrum of coins, the presence of Roman soldiers could be narrowed down to the period from around 370 to 400 AD. Fragments of several hundred vessels of various designs and origins were recovered from the pottery. The Terra Sigillata comes from pottery in the Argonne , simple utensils and jugs were obtained from the Eifel. A hand-made ceramic with a completely different design indicates strong Germanic influences in the region. Presumably they came to the Sponeck through federal councils or barbaric auxiliary troops. They also point to possible trade relations between the fort occupation and the Alemanni population living in the surrounding area. Finds of bronze dishes, metal fittings for boxes and chests and carefully crafted and decorated bone combs are rarer. The military element in the finds is mainly represented in the form of arrowheads and bolts for sling guns (balistae) . The equipment of the soldiers stationed here also included bronze brooches and belt fittings.

Hints

The camp is the only Roman fortress on the Upper Rhine between Basel and Mannheim that is still visible above ground. The preserved wall remains are in a fenced private garden and can only be viewed by prior arrangement. You can only see the complex relatively well from a point on a sidewalk above the fort. There is also a display board with a brief description and diagnosis plan of the system. You can see the restored remains of part of the eastern defensive wall and two corner towers. Most of the finds made in the fort are kept and exhibited in the Museum of Prehistory and Early History in Freiburg im Breisgau.

Monument protection

The ground monument is protected as a registered cultural monument within the meaning of the Monument Protection Act of the State of Baden-Württemberg (DSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

See also

List of forts in the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes

literature

- Roksanda M. Swoboda: A new late Roman fort on the Upper Rhine. In: Jeno Fitz (Ed.) Limes, files of the XL international Limes Congress (Székesfehérvár, August 30 to September 6, 1976). Akademiai Kiado, Budapest 1977, pp. 123-127.

- Roksanda M. Swoboda: The late Roman fortification Sponeck at the Kaiserstuhl (= publications of the commission for the archaeological research of the late Roman Raetia of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Munich contributions to prehistory and early history. Volume 36). With contributions by Lothar Bakker. CH Beck, Munich 1986.

- Philipp Filtzinger, Dieter Planck, Bernhard Cämmerer (Ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart, Aalen 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 .

- Hans Ulrich Nuber: The Sponeck - Late Roman bastion on the right bank of the Rhine . In: Edward Sangmeister (Ed.): Zeitspuren. Archaeological items from Baden . Archaeological News from Baden, No. 50, Freiburg 1993, p. 150.

- Gerhard Fingerlin : Borderlands in the Migration Period. Early Alemanni in Breisgau. In: Karlheinz Fuchs, Martin Kempa, Rainer Redies: The Alamannen . 4th edition. License issue. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1535-9 , pp. 103-110 (exhibition catalog, Stuttgart et al., State Archaeological Museum Baden-Württemberg et al., 1997–1998).

- Lothar Bakker: Bulwark against the barbarians. Late Roman border defense on the Rhine and Danube. In: Karlheinz Fuchs, Martin Kempa, Rainer Redies: The Alamannen . 4th edition. License issue. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1535-9 , pp. 111–118 (exhibition catalog, Stuttgart et al., Archäologische Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg et al., 1997–1998).

- Gabriele Seitz, Marcus Zagermann: Late Roman fortresses on the Upper Rhine. In: Badisches Landesmuseum (ed.): Imperium Romanum - Romans, Christians, Alamanni - The late antiquity on the Upper Rhine. Exhibition catalog for the state exhibition in the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe from October 22, 2005 to February 26, 2006. Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2005.

- Marcus Zagermann: Der Breisacher Münsterberg: The fortification of the mountain in late Roman times in: Heiko Steuer, Volker Bierbrauer (ed.): Hill settlements between antiquity and the Middle Ages from the Ardennes to the Adriatic , Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3- 11-020235-9 .

- Helmut Bender, Gerhard Pohl, Ludwig Pauli, Ingo Stork: The Münsterberg in Breisach, Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-10756-7 .

Remarks

- ↑ Seitz / Zagermann: 2005, p. 207.

- ^ Roksana M. Svoboda: 1977, p. 123.

- ^ Helmut Bender, Gerhard Pohl: The Münsterberg in Breisach. Volume I: Roman Times and the Early Middle Ages (= publication of the Commission for Archaeological Research into the Late Roman Raetia of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences ). C. H. Beck Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-10756-7 , p. 280.

- ↑ With the possession of Sponeck Castle, the right to levy ferry fees for the crossing over the Rhine was still connected in later times. Gerhard Fingerlin: 1998, p. 103.

- ↑ Helmut Bender: 2005, p. 324

- ↑ Helmut Bender: 2005, pp. 298-332

- ↑ Gerhard Fingerlin: 1998, p. 104.

- ↑ Ammianus, Res gestae 28,2,1 ff

- ↑ Ammianus, Res gestae 30,7,6

- ^ Gerhard Fingerlin: 1998, p. 106, Lothar Bakker: 1998, p. 117.

- ↑ Marcus Zagermann: 2008, pp. 165-185

- ^ Roksana M. Svoboda: 1977, p. 124.

- ↑ Gerhard Fingerlein: 1998, p. 104.

- ↑ Seitz / Zagermann: 2005, p. 207.

- ↑ Roksanda M. Swoboda: 1977, pp. 124-125.

- ^ Notitia dignitatum in partibus Occidentis V, 52-53; VII, 25; VII, 128.

- ↑ Gerhard Fingerlein: 1998, p. 104.

- ↑ Lothar Bakker: 1998, p. 123.

- ↑ Coin series: 2 Valentinian, 1 Valens, 1 Gratian, 1 Valentinian II or Arcadius, fragmented coin, second half of the 4th century AD.