Raetia

Raetia (also Rätien or Rhätia ) was a Roman province , named after the Rhaetians . It comprised the northern foothills of the Alps between the south-eastern Black Forest , Danube and Inn and reached in the south from the Ticino Alps (" Lepontine Alps ") via Graubünden and part of North Tyrol to an upper part of the Eisack Valley . At times it reached to about Schwäbisch Gmünd to the Rhaetian Limes northwest over the upper Danube. The Roman province was established decades after the military conquest in the first century AD and in the fourth it was divided into the southern / south-eastern Raetia prima ( Churrätia ) and the northern / north-western Raetia secunda . Their capitals were initially with high probability Cambodunum ( Kempten (Allgäu) ), later Curia Raetorum ( Chur ) and Augusta Vindelicum ( Augsburg ).

Their area only partially covered with the original settlement area of the Raetians . Since the 3rd century, the Germanic tribe of the Alemanni formed in their northwestern area . In the early 6th century it was under the Ostrogoths ; as a result, the tribe of the Bavarians emerged in their eastern area, with further intrusion by the Alemanni .

geography

The northern border of the province was also the border of the Roman Empire to the unconquered part of Germania, which was called Germania Magna . In the west, Raetia initially bordered the imperial province of Gallia Belgica , since its division under Domitian (81-96) to Germania superior , in the 4th century Sequana or Maxima Sequanorum instead . Vallis Poenina and Alpes Graiae et Poeninae bordered further to the southwest . Noricum was the eastern neighboring province. In the south lay the heartland Italy, which was not included in the provincial division until 300 AD ( Diocletian ) ( Gallia transpadana , Venetia et Histria ).

The boundaries went like this:

- The northern border and line of defense was formed by the Danuvius ( Danube ) between Castra Batava ( Passau ) and the Eining fort near Kelheim .

- To the west of it it was marked by the Upper Danube until around 95 AD and then by the 166 km long Rhaetian Limes , which extends from the Celeusum fort (Markt Pförring ) in a north-westerly direction to Gunzenhausen ( Altmühl ), from there in a south-westerly direction moved to Lorch (near Schwäbisch Gmünd ), where Raetia bordered Germania superior and the Limes continued to the north as Upper Germanic (→ ORL: route ). It was abandoned in the 3rd century, from then on the Upper Rhine , Lake Constance, Iller and, from the mouth of the Iller, the Danube formed the northern border of the province to Germania Magna (from west to east) . The new fortified border line of the Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes was created from the eastern Lake Constance to the Iller and from there northwards along the Iller to the Danube .

- The western border ran south from the outflow of the Untersee of Lake Constance via Ad Fines ( Pfyn ) into the area between Lake Zurich and Lake Walen to the Oberalp Pass , whereby the valley of the Linth (Glarus) and that of the Reuss (Uri) including the Ursern and the Haslital probably belonged to Raetia . and over the Furkapass (maybe) to the Fletschhorn .

- From there, the southern border stretched over the Splügen and Malojapass through the Vinschgau to Brixen (confluence of the Rienz and Eisack rivers ).

- The border with Noricum ran north through the Zillertal and then along the Inn ( Aenus , Oenus ) to the Danube.

- The course of the southern border of Rhaetia in today's Ticino and southern Graubünden is controversial in research. One side places the borderline on the main Alpine ridge, because the later expansion of the dioceses of Milan , Como and Novara makes it probable that the whole of today's cantons of Ticino and Misox as well as Bergell and Valtellina belong to three municipalities as early as Roman times. The other side counts the area of the Lepontier to Raetia and places the border south of a line between Domodossola - Locarno and Bellinzona . The Bergell and the Valtellina including Valposchiavo and Bormio are generally considered to be part of Italy. However, to this day neither side has been able to provide any decisive arguments or archaeological evidence.

Roman rule

Original residents

The names of the province, its later sub-provinces, its administrative centers ( Raetia , Vindelicia , Augusta Vindelicorum etc.) refer to the ethnic groups of the Rhaetians and the Vindelici , who, according to Roman sources, inhabited most of the province or until it was conquered by Rome had, whose repeated attacks on neighboring areas should also give rise to the decisive campaign of 15 BC. Have been.

The Raetians are said to have settled in the Alps north of the Como - Verona line . Various authors since ancient times considered them related to the Etruscans . Recent linguistic analyzes of Raetian and Etruscan inscriptions support this assumption; in any case, the people are now regarded as not Celtic (or even not Indo-European ). Roman authors described the Rhaetians as "warlike", prone to raids against neighboring peoples - which seemed to others to be an exaggerated pretext for Roman campaigns in the Alps.

Celts like the Venostes in today's Vinschgau or the (Indo-European, but not Celtic) Venetians are said to have settled in the same area . The latter gave its name to Veneto (the hinterland of Venice ), but Lake Constance was also sometimes called Lacus Venetus .

On his journey over the Alpine passes in 15 BC. BC Drusus met the Breonen ( Breuni ). Strabo calls them Illyrians (Indo-European, but not Celtic). From an archaeological point of view, however, they could also have been Raetians , in any case the Raetians were temporarily regarded as a Celtic-Illyrian mixed people (in contradiction to the latest linguistic findings). In fact, one can also come across the claim that the Breonen or even the Venosten were Rhaetian ethnic groups. So you can find different "interpretations" of the term Raeter . Horace classifies the Breonen as Vindeliker .

The Vindeliker settled at least in what is now Vorarlberg and Allgäu and from there perhaps as far as the Inn and Danube . They are generally considered to be Celts. Under the geography section , the article on the Vindeliker presents the difficulties in drawing conclusions from the sources on the connections or differences between the population groups listed. The Vindelikers, the Breonen and others were portrayed as particularly “warlike” and “lascivious” in addition to the councilors. A list of 46 in the Roman campaign of 15 BC. The Tropaeum Alpium contained the alpine peoples conquered in BC .

Roman advance to the Danube since 25 BC Chr.

Since 25 BC The northern border of the former province of Gallia cisalpina in northern Italy was moved to the Rhaetian settlement area, for example into the Valtellina ( Addatal ) and in the Adige Valley beyond what is now Bozen . The Roman general Drusus (stepson of Augustus ) moved in 15 BC. BC with an army over the Brenner pass and flanking over the Reschen pass into the area north of the Alps. Before that he had to break the Isarken ( Eisack Valley ) above Trient's violent resistance . In the same year his brother Tiberius , who later became emperor, conquered the area further west and reached Lake Constance via the Rhine valley, where the area of the Vindeliker was located. According to Strabo , he used an island on the lake as a base for the fight against the Vindeliker.

Gaius Iulius Caesar had until 51 BC Established the Rhine as the border of the Roman Empire. Between 35 and 28 BC BC Octavian and Marcus Licinius Crassus extended the Roman dominion in the Balkans on the lower Danube . In the following year 27, Octavian became Augustus. He came up with the plan to close the gap between the Rhine and the lower Danube and to defend Italy against Germanic incursions on the Rhine and Danube. The campaign of 15 BC BC also subjugated the Celtic kingdom of Noricum east of Raetias; Drusus and Tiberius conquered in 12 and 9 BC. Lastly, Pannonia neighboring the Noricum . This is how the Romans came to the Danube as a whole. This larger connection remained decisive over the next centuries (see Marcomanni and Augustan Alpine campaigns ).

Establishment and expansion of the province (1st / 2nd century)

Under the emperors Tiberius (14–37 AD) or Claudius (41–54 AD) the areas of today's Graubünden , Vorarlberg , southern Bavaria and Upper Swabia between western Lake Constance, the Danube and the Inn and northern Tyrol were established to the province (first military district) Raetia et Vindelicia combined - soon only called Raetia . Under Emperor Claudius, to secure the Danube line , a military road was built from the source of the Danube to shortly before Regensburg , accompanying the Danube near its southern bank and fortified with forts . This street is now called Donausüdstraße by historians . It was directly connected to Augsburg and Northern Italy by the Via Claudia . The Valais , initially also belonging to Raetia, was separated around 43 AD and merged as Vallis Poenina (or Alpes Poeninae ), an independent province or with Alpes Graiae .

In the following years Raetia grew northwest over the Danube (cf. Agri decumates ). Since Domitian (81-96) the establishment of the Rhaetian Limes was tackled, a structural marking and protection of the border of the area claimed by Rome, which was not based on waters or comparable geographical features. The northernmost point Gunzenhausen was reached around 90 AD . The Limes was completed as a building under Antoninus Pius (138–161) (→ ORL: Building History ).

Thus, "Raetia" not only reached around the area of the Vindeliker and further north beyond the presumed settlement area of the Raetians , rather their settlement area south of the Inn valley was added to the central area of Italy (former Gallia cisalpina , Roman citizenship). The Valtellina belonged to the later province of Gallia transpadana and today's region of Trentino-South Tyrol to Venetia et Histria . These were already before the northward crossing of the Alps in 15 BC. Acquired areas.

Probably under Emperor Trajan (98–117 AD) Augusta Vindelicorum (also Augusta Vindelicum; today Augsburg ) was raised to the capital of Raetias . It is very likely that the seat of the governor was previously in Cambodunum , today's Kempten . The province was administered by a governor ( procurator ) from the knighthood . During the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius , shortly before 180 at the latest, a legion ( Legio III Italica ) was stationed in Raetia . The governor ( legatus Augusti pro praetore ) was thus a senator of praetorical rank in the following decades .

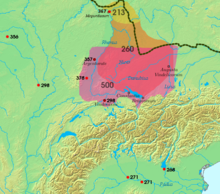

Retreat, Alamanni (3rd century)

At the beginning of the 3rd century under Septimius Severus , the Via Raetia was a second Roman road over the main Alpine ridge to Raetia. In the course of the imperial crisis of the third century , the imperial frontier that had been pushed forward over the Danube was gradually abandoned. Details are not completely clear from written sources; more recent archaeological findings play a larger role in the reconstruction of the processes at that time (→ Limesfall ). For a long time the Roman retreat had been related to a Germanic onslaught around 260; in fact, Germanic, namely Alemannic, plundering and destruction had repeatedly occurred since 230. The troops stationed in Raetia were increasingly thinned out. The use of Roman forces against the Goths and Sassanids on the eastern borders of the empire was given top priority. Attempts were made to counter this fact with fortress construction measures. In some forts, such as Pfünz , half of the double gates were bricked up, while others were reduced in area. Ever since Severus Alexander , a separation between military and civil violence could be observed at times. These were necessary measures because the Raetian Limes had become increasingly porous. Numerous Rhaetian cities, including those that were previously far in the interior of Rhaetia, and most of the smaller settlements had to be fortified and new small forts built in addition (for example, Schaan , Zirl , Castelfeder , Seebrück and Zenoberg / Meran ). The very weak crews of these forts probably only served to secure the roads. After 253 the provincial army is likely to have sunk to an all-time low. Their meager remnants were called milites provinciarum on the Augsburg victory altar around 260 , supported by populares (a kind of popular mobilization).

Nevertheless, the Alamanni soon advanced to Lake Constance (destruction of Brigantium / Bregenz around 260), but the Romans succeeded around 294 in stabilizing the border behind the Upper Rhine, Lake Constance and the Iller by building new types of fortifications. Around 320–330, the city wall of Augsburg was strengthened with rectangular defense towers protruding from the wall. The last known Roman inscription (today walled in the church Hausen ob Lontal) from the north of the Danube ( agri decumates ) dates from the time of the rule of Gallienus around 254. Between 260 and 280, the Decumatenland was abandoned by the imperial administration, and numerous forts were forced to do so be evacuated by their crews ( Limesfall ). Nevertheless, this region was still in the area of operations of the Roman army. However, there was no longer any reconquest and permanent occupation. The Rhaetian imperial border was never de jure, but de facto to the Danube and west of the Iller to Lake Constance and the Upper Rhine.

These new forts - not standardized in their ground plan - on this border mostly only had an inner area of 0.15 to 0.30 or 0.1 to 1.0 hectares, mighty defensive walls built using cast wall technology, semicircular or rectangular protruding towers, heavy fortified gates and stood on plateaus, ridges or spurs. They were manned by 120 to 300 men. The remainder of the fort at Eining / Abusina is also likely to have been built in the late 3rd century. Even in the civil settlement of Sontheim an der Brenz , the thermal baths, granaries and water reservoirs were surrounded by a wall. The establishment of a representative reception hall (auditorium) in Fort Kellmünz ( Caelius Mons ) around the year 310 is also noteworthy. This construction is likely to have been associated with the temporary presence of high-ranking dignitaries (including the Dux of the Raetian frontier army) and the Reception of Alemannic embassies (legationes) and their forwarding to the imperial court in Milan. Under the rule of Constantine I and his sons, Rhaetia was again relatively quiet until the middle of the 4th century. The garrisons newly stationed there (such as Guntia / Günzburg or Konstanz ) remained occupied until the 5th century.

In the abandoned Dekumatland between Main , Rhine, Neckar and Iller, the Germanic tribe of the Alamanni was formed from Suebian immigrants and the previous Celto-Roman population . In Eastern Franconia , the Alemanni were supposed to form the Duchy of Swabia (10th / 11th centuries, → Fig. ). Their settlement area is still recognizable today as the distribution area of the Alemannic dialect .

Division of the province (4th century)

In the course of the Diocletian Empire reforms of the early 4th century, Raetia became part of the Diocese of Italia and divided into the two sub-provinces Raetia prima ( Curiensis ) and Raetia secunda ( Vindelica ). These were now commanded by a Dux ( Dux Raetiae ) and administered by governors of lower rank, so-called Praesides . The praeses of the Raetia secunda resided in Augusta Vindelicorum ( Augsburg ), that of Raetia prima later in Curia ( Chur ), although it is uncertain whether it was not initially based in Brigantium ( Bregenz ) or Cambodunum ( Kempten ). The later German names "Churrätien" and "Vindelicien" were derived from the Latin names for Chur and Augsburg. The effective division of the province of Raetia probably did not take place before the reign of Constantine I, since in the laterculus veronensis written between 303 and 314 Raetia still appears as a province. The first mention of two separate provinces does not appear until Ammianus Marcellinus , probably after 354 (Amm. 15, 4, 1).

The dividing line and the areas of the sub-provinces are hardly apparent from sources. In the 19th and early 20th centuries one finds (also in historical maps ) the view that Raetia secunda has just covered the Alpine foothills between the Iller, Danube and Inn, Raetia prima Graubünden , the Northern Alps to Kufstein and the Austrian Central Alps to the Ziller .

Richard Heuberger opposed this view since 1931. Since then, the dividing line has been indicated as starting approximately at Isny , over the Arlberg and then approximately along the present-day border between Switzerland and Tyrol (“ Münstertal ” - “ Stilfserjoch ”). One adheres to the assumption that Raetia prima essentially comprised the original settlement area of the Raetians and Raetia secunda that of the Vindeliker ; however, these settlement areas themselves are not clear. Heuberger's thesis that the dividing line coincided with the later border between the dioceses of Chur and Säben-Brixen was also decisive .

The fact that today's Graubünden belonged to the Raetia prima and the Alpine foothills east of the Iller to the Raetia secunda is obviously beyond question, the uncertainty mainly concerns the affiliation of the Vinschgau , the Inn valley between Ramosch and Landeck , as well as the area between the Iller, Argen and the mouth of the Alpine Rhine .

From 357 to 358 the Raetia II suffered from massive attacks by the Juthungen and Suebi . The Juthung began to besiege heavily fortified cities. Around 360 the settlement of the area around Regensburg, Straubing and Künzing broke off by these incursions. The survivors withdrew to the legion fortress Castra Regina , which was only partially used by the heavily reduced legio III italica . The supply of the border troops became increasingly a problem, since Septimius Severus the supplies for the III Italica were organized from Trento. Towards the end of the 4th century, the province had to bear this burden itself for the most part (annona / onera Raetia) . On several occasions it was decreed by decree that the provincials may not evade their tax obligations (munera sordida) , also an indication that these are probably difficult to collect. Raetia I was supplied via the Bündner passes, while Raetia II was connected to Italy via the old Via Claudia Augusta and the newer Via Raetia . The last milestones on the Brenner Pass date from the time of Julian Apostatas.

From 369, under Valentinian I , an extensive fortress building program was started at the borders, which essentially included the erection of two-story, rectangular watchtowers (burgus) (8 to 12 meters wide, 10 to 12 meters high) and warehouses ( Horrea ; in Rostro Nemaviae near today's Türkheim , Lorenzberg , Schaan , Eining , Bregenz ) provided for the Raetia II border troops to counter the recurring crop bottlenecks due to fallow fields (agri deserti) . The construction of the large warehouses in Innsbruck - Wilten / Veldidena and Pfaffenhofen / Pons Aeni falls in the 2nd quarter of the 4th century. The Notitia also names a head of the imperial magazines (Praepositus thesaurum) for Augsburg . Warehouses that had existed for a long time, such as the one in Wilten, were repaired or re-attached. The Burgi were mainly used to secure the traffic routes, especially the border passages (aditus Raetici) and the state postal service. From 383 to 384 there was another massive incursion of the Juthungen (instigated by the British usurper Magnus Maximus ), who could easily be persuaded to do so by the unusually rich harvest. The majority of the provincial population now lived in fortified hilltop settlements or in the larger cities.

Alamanni, Franks, Ostrogoths and Baiern: Raetia and the end of antiquity

In the early 5th century, the forts on the Iller and the Upper Danube were mostly manned by strongly Germanized units. This is proven by grave finds from Bürgle, Burghöfe (Mertingen) and Finningen. In 401 Stilicho led a campaign against the Alemanni and Vandals who had invaded Raetia , repulsed them with the help of the dux Raetiae Jacobus and concluded a peace treaty with them. He then fought - apparently with the participation of Rhaetian troops - the Visigoths of Alaric in Italy, who were besieging the imperial court in Milan. Due to the drying up of found coins, this was previously interpreted as the complete evacuation of the Danube Limes by the Romans, but Claudian does not find any evidence of such a drastic measure. It is also unclear whether Stilicho actually ordered all units to Italy without exception. Rather, the detached departments seem to have returned to their old locations soon after their deployment in Northern Italy. For 430 fights between Juthungen and an army under Flavius Aëtius (magister equitum praesentalis) are reported in Raetia II, in 431 he also took action against rebellious Noriker (Nori rebellantes) and Vindeliker. In this context, an inscription from Augsburg (Domplatz) also names the units of the Pannoniciani , Angrivarii and Honoriani . Augsburg was probably one of the last strongholds of the Roman provincials in this region at that time. In the course of the fifth century Germanic groups crossed the northern borders of the Roman Empire almost unhindered; the transalpine part of the Raetia ( Raetia secunda / Alpine foothills) was also affected by this. Some of the attackers were plundering gangs who took advantage of the increasing neglect of the Roman border defense. On the other hand, there were warrior associations that were recruited by the Romans to fight as foederati against internal and external enemies; after the collapse of the western Roman central government, they founded their own empires. Various developments, about which the written sources are silent, can be traced with the help of archeology.

The Roman border forts on the Danube were gradually abandoned around the middle of the 5th century, less because of military attacks, more because military service came to a standstill due to a lack of supplies (mainly due to dwindling salary payments). A biography of Severin von Noricum (around 410–482) from the early 6th century, the Vita Sancti Severini written by Eugippius , describes this turning point. According to her, the Roman military camps Quintanis ( Künzing ) and Batavis ( Castra Batava , Passau ) of the Raetia secunda were last evacuated around 470 , in fact under the impression of constant raids by plundering Alemanni; archaeologically, this is confirmed with reservations.

In Günzburg and Kellmünz grave finds with roller-stamped Argon sigillata have emerged, which prove the presence of the units of the milites Ursarienses and the cohors III Herculea Pannoniorum in these bases for over 400 years. The presence of Limitanei in forts on the upper Danube and between Iller and Lech is documented up to around 420 or 430, and it is possible that they were still at their posts here until the middle of the 5th century. On the other hand, one can only speculate about the timing of the abandonment of the Valentinian watchtowers in western Raetia; It is nowhere possible to determine it with absolute certainty. The investigations of the fire horizons in the Burgi on the middle Iller and between Kempten and Bregenz suggest their destruction for the period between the late 4th and early 5th centuries. The Burgus of Finningen seems to have been occupied by possibly Germanic mercenaries until at least 408. This could be two gold coins (solidi) of Arcadius and the British Emperor Constantine III. (407–411), which were found near the fortification and may be regarded as pay. Constantine III seems to have brought this area under his control in the course of his border security measures from Gaul . A solidus 407/408 found in Finningen was minted in Lugdunum , Lyon .

Today research puts the end of the organized late Roman Limes in Bavaria in the middle of the 5th century. Evidently, however, the Roman or Romanized life in Raetia did not break off suddenly. Particularly at militarily secured locations, which had relatively strong units and where there was probably a close connection to local civil life, clear findings can still be made over a longer period of time. Other garrisons, however, were completely evacuated or violently destroyed, such as Fort Eining on the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes. The development in the various regions of the province was probably very different. Evidence of Roman survival can be found in Chur , for example , which, along with its surrounding area, was well protected behind the Bündner passes and became a bishopric from 451 onwards. Even in the late antique garrison town of Augsburg, the city population was able to enjoy modest prosperity and relative security due to the protection of its city wall and the stationing of a mounted guard unit, the Equites stablesiani seniores , as well as smaller contingents of the Limitanei and the Comitatenses . For the late antique fortress town of Castra Regina (Regensburg), a seamless continuity of the location can be proven archaeologically. The presumed location of the remaining garrison there forms the location of the later Agilofingian ducal palace. The final extinction of Roman administration and border defense seems to have come at the latest in 476 in the course of the deposition of the last Western Roman emperor Romulus Augustulus . The above-mentioned Vita Sancti Severini , a detailed document about the collapse of Roman power on the Upper Danube, gives important insights into the events of that time. Occasionally afterwards there were still regular soldiers who stayed at their posts, but these should usually not have been paid for years and have long since lost the courage to take initiative. The biography also provides information that a regular unit, the Numerus Batavinus , was stationed in the late antique fortress town of Batavis (Passau) . Possibly this number was in an inland or residual fort within the walls of Batavis, since the late antique Boiotro fort on the other side of the inner side was probably no longer occupied in the late 5th century according to the findings. Eugippius sums up the collapse of the border defense in the following words:

“ At the time when the Roman Empire still existed, the soldiers in many cities were paid for guarding the Limes from public funds (publicis stipendiis alebantur) . When this regulation ceased, the military units fell apart with the Limes . "

From the point of view of the provincials who stayed behind, the withdrawal of the military was a catastrophe in two respects. They were now completely on their own and the already low standard of living sank even further because the soldiers were also unable to act as trading partners. The population also decreased, as many also - as in Ufernorikum - according to Eugippius migrated to the safer south.

" All the provincial residents who left their cities [...] and were assigned foreign residences in different areas of Italy followed the same path ."

But even after the withdrawal and dissolution of the Roman border army, a number of well-developed fort sites remained focal points for a mixed Romanic-Germanic population. In some cases, newly arriving Germanic tribes also settled in abandoned and destroyed troop locations. In the 6th or 7th century Bavarians founded the village of Oweninga north of the Roman ruins of Eining and converted the former guard post on the Weinsberg into a Christian place of worship.

There was a lively cultural exchange and trade relations with the Alemanni tribes living on the other side of Lake Constance. Other forts are likely to have been abandoned. In the Vita Sancti Severini it says:

" ... because like the other forts [...] it will be deserted and abandoned by its residents. "

(The following information is given in the article Bajuwaren : Ethnogenesis , see also Raetia secunda .)

Pro forma the Germanic military leader Odoacer , who had deposed the last Roman emperor, claimed Raetia for his kingdom of Italy. From around 500 onward, Alemanni began to settle more frequently, although at least parts of the Romanized Celtic civilian population will have remained in the country, as a large number of corresponding place and river names have been preserved. The Alamanni of the northern district, defeated in 496 by the Franks under Clovis I , faced Clovis again in 506, where they suffered a final defeat in the battle of Strasbourg . Their districts now fell irretrievably to the Franks, which brought the Alemanni resident there to flee. These now fled to Raetia, which at that time was subordinate to the Ostrogoth warriors' association ; whose rex Theodoric took them into his empire in 506 AD, according to a note from Magnus Felix Ennodius , because he hoped they would provide better border security against the advancing Franks. Theodoric turned to his brother-in-law Clovis I and interceded for the Alamanni, but recognized Clovis's anger as justified. He asked only to punish the guilty and recommended moderation in the penalties. Theodoric promised that he would see to it that the Alemanni, who were in Roman territory in Raetia, also kept quiet for their part. Between the lines, Theodoric made it clear that he was making a claim to the disputed territory of Raetia and that the Alemanni would be used as leverage against Clovis if Clovis did not recognize his supremacy there.

The settlement area of the Alemanni extended now at the latest from the Iller to over the Lech . East of Lech, which most historians and archaeologists of today originated from the remaining Celtic Vindelikern , the Roman civilian population, the immigrant Alemanni and other groups ( elb -) Germanic tribes such as the Marcomanni a new Germanic major unit, the Bavarians or Baiern (see ethnogenesis ). In contrast to older opinions, there are apparently no indications of an immigration of a pre-existing, uniform Bavarian tribe from today's Bohemia , as there is extensive continuity of the population in the Alpine foothills even after the collapse of the Roman Empire. However, this development also affected the (former) Roman province of Noricum across the Inn .

Excavations show that the areas belonging to Raetia I continued to maintain close connections with the Italian motherland, certainly also because they belonged to the Ostrogothic Empire between 493 and 536. Despite all the uncertainties about the transition from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, some forts, such as Arbon , Bregenz and Konstanz , were the nucleus for the development of prosperous medieval cities. The connections of the transalpine Raetia to the south were from now on, at the latest since the defeat of the Ostrogoth empire by the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian around 540, no longer politically determinative, and so the Roman culture and Latin language gradually lost their influence. However, Celtic and Roman terms and place names survived in the vocabulary of the remaining mixed population. Around Lake Constance, Irish monks around Pirminius found Christian communities that were heavily overgrown in the 6th century. New churches and monasteries followed on the Reichenau .

In the southern, alpine area of the earlier Raetia (especially the Raetia prima ), the political and, above all, cultural connection to Italy remained for a long time, and the Latin or Romance language and the Christian faith survived the migration period . The name Raetia was later only used for areas in the Raetia prima . The German name Churrätien also appears .

Further division in the Middle Ages

In addition to a north-south divergence due to the dwindling of Roman control over the Alpine foothills, an east-west division of the earlier Raetia formed or consolidated :

- The Alemanni not only settled the Alpine foothills of the Raetia secunda up to over the Lech, but also areas around Lake Constance in the area of the Raetia prima . In the 10th century, the Grisons Churrätien merged with these and the Alemanni, who settled in the earlier Raetia secunda and further northwest, to form the Duchy of Swabia .

- The Bavarians not only shaped the culture of the Raetia secunda east of the Lech , but also gradually took possession of the entire earlier Raetia south of this area (in the sense of the Duchy of Bavaria ).

The Romansh - its independent forms formed in the area of the Raetia are summarized as Rhaeto-Romance languages - could only survive in the south of the earlier Raetia (Raetia prima) . ( Romansh in the narrower sense is the Romansh of Churrätiens / Graubünden , the Bündner Romansh .) The Christian faith (and the Latin language) was cultivated by the bishops in Chur and Säben (?) And Brixen . The Raetia secunda disintegrated culturally and politically along the Lech ( Lechrain ), the Raetia prima formed Churrätien, initially represented by the Diocese of Chur , which ruled the Inn Valley only up to Finstermünz . From there on, the former Raetia belonged to the diocese of Säben-Brixen . Around 550 the western former Raetia up to the Lech and in the south including Churrätiens is under Franconian sovereignty . However, the Franks allowed the religious system and thus also the language and culture of Churrätien to exist. East of the Lech, the Bavarian duchy is first attested in 555, it was only under Charlemagne that this, and thus the entire eastern part of the earlier Raetia, also came under Frankish sovereignty (788).

The demarcation that still exists today at Finstermünz through the Inn Valley is consolidated with the rise of the County of Tyrol since the 12th century in the east and with the alliance of the population of the Diocese of Chur in the west against the efforts of Bishop Peter von Kaunitz from Bohemia, his area of his friends to be transferred to the Habsburgs ( Gotteshausbund 1367). This alliance followed the example of the Swiss Confederations in the western neighborhood and ultimately (not before 1814) led to the integration of the landscape into today's Switzerland . The county of Tyrol, however, fell permanently to the Habsburgs in the 14th century; It is based on this that the eastern part of the alpine Raetia is now divided between Austria and Italy .

Raetia from the 18th century to the present day

The geographical term "Raetia" was used throughout the Middle Ages and increasingly again in the 18th and 19th centuries for the Free State of the Three Leagues . When the Free State of the Three Leagues was incorporated into the Helvetic Republic as a new canton on April 21, 1799 , it was initially called Raetia and later Graubünden . To this day, the adjective “Rhaetian” or “Rhaetian” is used alternatively for “Graubünden” or “-bündner” - for example for the Rhaetian Railway or the Rhaeto-Romanic .

Settlements, cities, places and bodies of water

| Cities / settlements / places in Raetia | Today's name | Waters in Raetia | Today's name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abodiacum , Abudiacum, Abuzacum | Epfach | ||

| Abusina | Eining, district of Neustadt a. d. D. | ||

| Ad ambergris | Schöngeising ? | Amber, amber | Ammer, Amper |

| Ad Fines | Pfyn (border to Germania Sup. ) | ||

| Ad Lunam | Urspring Castle | ||

| Ad Novas | Iging | ||

| Ad Rhenum | St. Margrethen | ||

| Aeni Pons, Aenipontum | innsbruck | Aenus, Oenus | Inn |

| Alae | Bask | ||

| Alkimo tennis | at Kelheim | ||

| Aquilea, Aquileia, Aquileja | Heidenheim an der Brenz | ||

| Arbor Felix | Arbon | ||

| Artobriga | ?? | Athesis | Etsch |

| Augusta (e) | Near Straubing | ||

| Augusta Vindelicum | augsburg | Licca, Licus | Lech |

| Batava, Batavis , Boiodurum | Passau | ||

| Bilitio | Bellinzona | ||

| Biriciana | Weißenburg in Bavaria | ||

| Bragodunum (-urum) | ?? | ||

| Bratananium | Gauting | ||

| Brigantia, Brigantium , Brecantia | Bregenz | Brigantinus lacus | Lake Constance |

| Burgus Centenarium | Burgsalach | ||

| Caelius Mons , Mons Caelius | Kellmünz on the Iller | ||

| Cambodunum , Cambidunum | Kempten (Allgäu) | Ilaraus, Hilara | Iller |

| Casillacum, Cassiliacum | possibly Memmingen , Ferthofen or Lachen (Swabia) | ||

| Castra Augusta | Geiselhöring | ||

| Castra Batava , Batavorum, | Passau | ||

| Castra Regina , Reginum | regensburg | Danuvius | Danube |

| Celeusum | Pförring market | ||

| Clunia | Feldkirch | ||

| Constantia | Constancy | ||

| Cunus aureus | Splügen Pass | ||

| Curia | Chur | ||

| Dormitory | Dormitz (district of Nassereith / Tyrol) | ||

| Esco | (at the Wertach crossing) | ||

| Foetes | Pfatten near Branzoll | ||

| Fetus, fauces | Feet | ||

| Forum Tiberii | ?? | ||

| Germanicum | Koesching | ||

| Guntia, Gontia (e), Contia | Gunzburg | Guntia | Gunz |

| Iciniacum | Theilenhofen | ||

| Inutrum | Nauders am Reschenpass | ||

| Iovisara | ?? | Isarus, Isara | Isar |

| Isinisca, Isunisca | ?? | ||

| Lapidaria | Other | ||

| Magia | Maienfeld | ||

| Matreium | Matrei am Brenner | ||

| Navoae | Eggenthal in the Allgäu | ||

| Parrodunum | Burgheim | ||

| Parthanum, Partanum | Partenkirchen | ||

| Petrenses | Vilshofen on the Danube | ||

| Phoebiana | Faimingen (in the opinion of Robert Knorr : Finningen ) | ||

| Pinianis | Bürgle (Gundremmingen) | ||

| Pons Aeni , Ad Aenum | Pfaffenhofen am Inn | ||

| Pons Drusi | Street station near Bozen | ||

| Pontes Tesseni | ?? | ||

| Quintanis | Künzing | ||

| Rapae | Schwabmünchen | Rhenus | Rhine |

| Rostrum Nemaviae | Türkheim | ||

| Sablonetum | Ellingen | ||

| Scarbia | Scharnitz near Mittenwald | ||

| vicus scuttarensis | Nassenfels | ||

| Sorviodorum | Straubing | ||

| Subsavions | Klausen / Säben (South Tyrol) | ||

| Submuntorium , Submontorium, Sum (m) untorium | Burghöfe (Mertingen) | ||

| Tasgetium | Eschenz | ||

| Teriolae, Teriolis | Zirl | Ticinus | Ticino |

| Umiste | Imst | ||

| Urusa | Raising | ||

| Vallatum | Manching | ||

| Veldidena , Vetonina | Wilten - Innsbruck | ||

| Vemania | Large wood people ( District of Wangen ) | ||

| Venaxamodurum | Neuburg on the Danube | ||

| Viana | possibly Memmingen or Ferthofen | ||

| Vimana | Isny in the Allgäu | Virda, Virdo | Wertach |

| Vipitenum | Sterzing |

Many river names were borrowed from Celtic . The name Ries for the landscape around Nördlingen comes from Raetia .

In the sources (literary texts, Tabula Peutingeriana , Itinerarium Antonini , Notitia dignitatum , milestones ) the names of the settlements are only given in the nominative in the rarest of cases , rather, by nature, in the locative ("Where?"), Accusative ( "Where to?") Or ablative ("Where from?"). The implementation from the respective case is often not easy, sometimes impossible, even if the etymology fails.

See also

| Ethnicities and languages | Geographical areas | administration |

literature

- Rudolf Degen: The Raetian Provinces of the Roman Empire. In: Historical antiquarian society of Graubünden (ed.): Contributions to the Raetia Romana. Requirements and consequences of the incorporation of Raetia into the Roman Empire. Terra Grischuna, Chur 1987, ISBN 3-908133-37-8 , pp. 1-43.

- Ferdinand Haug : Raetia . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IA, 1, Stuttgart 1914, Col. 46-62.

- Richard Heuberger : Raetia in antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Research and Representation. Volume I. Wagner, Innsbruck 1932. (Schlern-Schriften Vol. 20; Newprints Scientia, Aalen 1971 and 1981)

- Reinhold Kaiser : Churrätien in the early Middle Ages. Late 5th to mid 10th century . 2nd, revised and supplemented edition. Schwabe, Basel 2008.

- Andreas Kakoschke: The personal names in the Roman province of Raetia . Olms, Hildesheim 2009. (Alpha-Omega, Row A; 252)

- Gerhard Rasch: Ancient geographical names north of the Alps . de Gruyter, Berlin 2005. ISBN 3-11-017832-X ( Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , supplementary volumes 47; originally published in 1950 as a Heidelberg dissertation, with exhaustive information on the sources).

- Franz Schön: The beginning of Roman rule in Raetia. Sigmaringen 1986. ISBN 3-7995-4079-2

- Felix Staehelin : Switzerland in Roman times. Third, revised and expanded edition. Schwabe, Basel 1948.

- Gerhard H. Waldburg: Raeti, Raetia. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 10, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01480-0 , Sp. 749-754.

- Gerold Walser : The Roman roads and milestones in Raetia . Württembergisches Landesmuseum, Stuttgart 1983. (Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany No. 29)

Web links

- Alfred Hirt: Raetia. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Adolf Collenberg: Rhaetians. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Rhätia . In: Heinrich August Pierer , Julius Löbe (Hrsg.): Universal Lexicon of the Present and the Past . 4th edition. tape 14 . Altenburg 1862, p. 98 ( zeno.org ).

Among other things on geography:

- Raetia Province (www.imperiumromanum.com)

- Roman province of Raetia (www.antikefan.com, map)

Geography only:

- Gaul, Britannien, Danube Provinces (www.maproom.org) Raetia is the left of the green bordered Danube provinces right below the center of the picture. Click more than once to zoom in on a return to overall view with Refresh (F5); or click on the navigation symbols at the bottom. It is map 11 from: Heinrich Kiepert : Atlas antiquus . 5. rework. u. probably edition Reimer, Berlin 1869.

- Places and locations in the Roman provinces (Italian)

- Places and course of the Limes (German Limes Commission)

Source of article text:

Illustrative:

- 1200 years of Ludenhausen (Lech / Ammersee). ( Memento from February 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Pictures, Via Claudia Augusta , successful depiction of the history of the Roman Raetia

- Claus-Peter Lieckfeld: Bavaria: Raetia should live! In: Spiegel Online . March 30, 2005, accessed on May 12, 2015 (first published in “Merian extra” Germany , Dec. 2004): “This could have been the report of a legate to Emperor Claudius II.”

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b imperiumroman.com after Ernst Meyer: Raeti, Raetia. In: The Little Pauly (KlP). Volume 4, Stuttgart 1972, column 1330 f.

- ↑ Handbuch der Schweizer Geschichte, Vol. 1. Zurich 1972, p. 68. Cf. also the detailed, albeit older, discussion in: Richard Heuberger: The West Border Rätiens , in: Praehistorische Zeitschrift XXXIV, Vol. V, 1949/50, p 47-57. Full text (PDF; 4.25 MB) ( Memento from December 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ You argue with a passage in Ammian 15, 4, 1 " imperator ... in Raetias camposque venit Caninos ", whereby according to Sidonius Apollinaris , carm. 5, 373ff. and Gregory of Tours , Hist. Franc. 10.3 the Campi Canini was an area south of the Alps around Bellinzona. Pliny also mentions nh 3, 133f. the Lepontier not in the enumeration of the peoples who were assigned to an Italian township. Staehlin, Die Römer in der Schweiz , p. 111. Stählin refers in particular to the work of Heuberger and Oechsli (Mitteilungen der Antiquarian Gesellschaft Zürich (MAGZ), 26, 1 [1903] 69.)

- ↑ Handbuch der Schweizer Geschichte Vol. 1, p. 68. For a complete overview of the literature, see here.

- ↑ a b c Strabon Geography IV, 6, 8

- ↑ a b c History of Tyrol: Via Claudia Augusta

- ↑ Venostae in Atlas Antiquus

- ↑ So also in the Atlas Antiquus

- ↑ Breuni . In: Heinrich August Pierer , Julius Löbe (Hrsg.): Universal Lexicon of the Present and the Past . 4th edition. tape 3 . Altenburg 1857, p. 299 ( zeno.org ). According to this, the Breuni were mentioned in the 9th century under the name Pregnarii .

- ^ Atlas Antiquus

- ↑ a b Horace Carm. IV, 14th

- ↑ See Fritzens-Sanzeno-Kultur

- ↑ Richard Heuberger analyzes the different meanings that the expressions Rhaitoi , Raeti , Rhaeti assume in ancient sources : Die Räter in the magazine of the German Alpine Association , Bruckmann, Munich 1939, pp. 186–193. homepage.univie.ac.at (PDF; 5.89 MB).

- ^ Elisabeth Hamel: The Raetians and the Bavarians. Traces of Latin in Bavarian. In: Bernhard Schäfer (Ed.): Land around the Ebersberger Forest. Contributions to history and culture. 6 (2003) ( Memento from November 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), Historical Association for the District of Ebersberg eV, ISBN 3-926163-33-X , pp. 8-14

- ^ Richard Heuberger: Tyrol in Roman times . In: Hermann Wopfner, Franz Huter (Ed.): Yearbook for History and Folklore , XX. Volume, Tyrolia, Innsbruck / Vienna 1956, pp. 133-138. Full text (PDF; 1.38 MB) ( Memento from December 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b History of Tyrol: Roman Invasion

- ^ Strabo Geographie VII, 1, 5 - relevant sentence

- ↑ Critical to this, Vindeliker: Geschichte

- ↑ On the occasion of Switzerland in Roman times ; on the uncertainty (“or”) history of the Valais

- ↑ See Tyrol ; search for "Isarco" ( Pons Drusi statio = Bozen ) or "fiume Adda" in Roma Victrix Regiones ( memento of the original from March 28, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Gerhard Weber in: Gerhard Weber (Ed.): Cambodunum - Kempten. First capital of the Roman province of Raetia? Special volume Antike Welt, von Zabern, Mainz 2000, p. 43f .; Wolfgang Czysz in: The Romans in Bavaria. 1995, p. 200; Tilmann Bechert : The provinces of the Roman Empire. Introduction and overview. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2399-9 , p. 152.

- ↑ CIL 3, 5933

- ↑ Mackensen 1995, pp. 100-106; ders. 1999, pp. 223-228.

- ^ Kaiser, Churrätien in the early Middle Ages, p. 16.

- ↑ Most recently Georg Löhlein: The Merovingian Alps and Italy Policy in the 6th Century . Erlangen 1935, p. 21f.

- ^ Richard Heuberger: "Raetia prima and Raetia secunda". In: Klio 24 (1931), pp. 348-366.

- ↑ So most recently in Col. 753 by: Gerhard H. Waldburg: Raeti, Raetia. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 10, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01480-0 , Sp. 749-754. DNP refers to Thomas Fischer: Spätzeit und Ende , in: Wolfgang Czycz, Karlheinz Dietz, Thomas Fischer, Hans-Jörg Kellner: Die Römer in Bayern , Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 358–404, where the same limit is given without any apparent evidence is. Critical to the same alleged borderline Rudolf Degen: The Raetian Provinzen , p. 31.

- ↑ Reinhold Kaiser: "Churrätien and the Vinschgau in the early Middle Ages". In: Der Schlern 73 (1999), pp. 675-690.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus XVII 6.1.

- ↑ Fischer 1990a, Moosbauer 1997th

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus 11,19,4 (May 24, 398).

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus XXVIII 2.1.

- ↑ ND occ. XI 30

- ↑ Mackensen 1994b, pp. 505-513, ders. 1999, pp. 234-238.

- ↑ Ambrosius epist. XVIII 21; XXIV 8.

- ↑ Cat.152e, Keller 1986.

- ↑ D. Woods: The early career of the mag. equ. Jacobus . In: Classical Quarterly . Volume 41, 1991, pp. 571-574.

- ^ Karlheinz Dietz : Regensburg in Roman times . 1979.

- ^ Sidonius carm. VII 233; Hydatius chronica XCIII; XCV, Ralf Scharf 1994.

- ↑ Ralf Scharf: The Iuthungen campaign of Aetius. A reinterpretation of a Christian epitaph from Augsburg . In: Tyche . Volume 9, 1994, pp. 139-145.

- ↑ See last Henning Börm: Westrom. From Honorius to Justinian . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2013.

- ↑ Heuberger, Rätien , p. 122f.

- ↑ Concrete p. 409 from (for paragraph): Thomas Fischer: Spätzeit und Ende or From the Romans to the Bavarians. The Alpine foothills in the 5th century. In: Wolfgang Czycz, Karlheinz Dietz, Thomas Fischer, Hans-Jörg Kellner (eds.): The Romans in Bavaria. Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 358-404 and 405-411.

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz : Gontia - Günzburg in Roman times. Likias-Verlag, Friedberg 2002, ISBN 3-9807628-2-3 , p. 222.

- ↑ Ulmer Museum (ed.): Römer an Donau and Iller - New research and findings. Book accompanying the exhibition, Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Sigmaringen 1996, ISBN 3-7995-0410-9 , p. 150; Fig.p. 151.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , p. 45.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , p. 203.

- ↑ Qua consuetudine desektiven [sc. publicis stipendiis] simul militares turmae sunt deletae cum limite […] ( Vita Severini , Chapter 20, 1).

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , pp. 194-196.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , pp. 45-46.

- ^ Vita S. Severini 44.7.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer and Konrad Spindler: The Roman border fort Abusina-Eining . Theiss, Stuttgart 1984. (Guide to archaeological monuments in Bavaria: Niederbayern 1), ISBN 3-8062-0390-3 . P. 100 ff.

- ^ Vita S. Severini 22.2.

- ↑ Julius Cramer: The history of the Alemanni as a Gau story. 1899, p. 220 f.

- ↑ See the homepage of Pankraz Fried .

- ↑ To a correct classification of the places endeavors: Gerhard Rasch: Ancient geographical names north of the Alps . de Gruyter, Berlin 2005. ISBN 3-11-017832-X (Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, supplementary volumes 47).

Coordinates: 47 ° N , 9 ° E ; CH1903: 684,713 / 246066