Aalen Castle

| Aalen Castle | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 66 ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) | Rhaetian Limes, route 12 |

| Dating (occupancy) | at 150/155 to at the latest by 259/60 AD |

| Type | Alenkastell |

| unit | Ala II Flavia milliaria |

| size | 277 × 214 m = approx. 6.07 ha |

| Construction | stone |

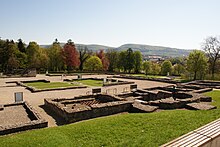

| State of preservation | Foundations of the Principia and the Porta principalis sinistra secured |

| place | Bask |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 50 '8.1 " N , 10 ° 5' 5" E |

| height | 447 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Unterböbingen fort (southwest) |

| Subsequently | Fort Buch (northeast) |

The fort Aalen was a Roman military camp , which in the 2nd century close to the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes , a World Heritage Site was built and is now partly built over in the hallway wall fields in the field of district town of Aalen in Ostalbkreis in Baden-Württemberg is located. As the largest garrison on the Rhaetian Limes, the fort built for an elite mounted unit (Ala miliaria) is of particular importance. The sixteen identifiable epigraphic testimonies are of extremely high historical value for research. The current city name Aalen could be traced back to the Latin word Ala .

location

The fort site was at least partially settled in prehistoric times. This is indicated by a thin Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age settlement horizon west of the Roman north-west gate. The military installation with its praetorial front (front) facing northeast was built in a topographically best location on a slope sloping towards the Kocher . From there it is possible to observe not only the valley of the Kocher, but also the recesses of the Rems and Hirschbach that flow into it. The Kocher flows north, following the north-eastern valley floor of the slope, while from the southwest, directly under the southeast wall of the camp, in the Rems valley, the small river Aal encounters the Kocher. The Hirschbachtal, which is exactly opposite and emerges from the eastern slope of the Kocher, can also be seen. Only the western rear front of the garrison has limited visibility, as the slope covered with ancient buildings rises a little higher and then drops into the bottom of the Rombach . This brook, coming from the north, joins the Sauerbach in the Remstal and flows into the Kocher as an eel. The eel was particularly important for the water management of the fort and camp village (vicus) . The extraction and smelting of iron ore has been proven in the vicinity of Aalen.

Research history

Like the possibly Germanized name of the city of Aalen itself, the field name Maueräcker indicates an old settlement. The knowledge of their existence has obviously never been completely extinguished on site. As Konrad Miller reported in 1892, the Schlettstadt humanist Beatus Rhenanus wrote about extensive Roman foundation walls in Aalen in 1531 . During this time, the ruins were searched for well-salable antiquities from antiquity. A report from the period shortly after the middle of the 19th century is known of recent excavations. At that time, the local history researcher Hermann Bauer dug in a place that can no longer be located today and came across the remains of a bath. In 1882, the state curator Eduard Paulus the Younger and Ludwig Mayer again uncovered a bathing facility north of the cemetery. The investigations reinforced the suspicion that there was a military installation in Aalen. In 1890 the fort and its dimensions were discovered. But only the excavations of the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) under the route commissioner Major Heinrich Steimle and under Felix Hettner were able to give Roman Aalen a face in 1894 and 1895. At that time the fort square was not yet built over. It was not until the Limes Museum was built in 1964 in the middle of the north-western ancient Via principalis and directly behind the Porta principalis sinistra , the left gate of the Via principalis, inside the camp that further investigations were carried out. From 1977 onwards, digging began again, and between 1978 and 1986 the staff building, the Principia , of the fort was exposed under the direction of Dieter Planck . The square extension of the museum, which opened in 1981, pushed even further above the ancient floor almost to the large transverse hall of the Principia . The investigations in 1988, 1997 and 1999 were devoted to the fortification of the camp. Between April and August 2004, the building complex to the west of the staff building, which Planck had already cut through between 1979 and 1981, as well as a section of Lagerringstrasse before it was partially built over with the reconstructed segment of a team barracks, was thoroughly examined by the archaeologist Markus Scholz .

The partly very dense, partly patchy overbuilding of the fort and vicus in the 20th century has not only changed the largely authentic location, but also, especially in the rear part of the camp (Retentura) with construction work in the 1930s, irretrievable destruction without previous excavations caused. The municipal cemetery, which covers almost the entire front storage area (Praetentura), also makes research there impossible. Despite the construction of the Limes Museum and the highlighting of Aalen's special historical past by committed archaeologists such as Philipp Filtzinger (1925–2006), the state of Baden-Württemberg and the city bought the land in 1977, and there was a great risk of building the last researchable central storage area (Latera praetorii) to lose.

Building history

The almost rectangular, 277 × 214 meters (6.07 hectares) equestrian fort became the most important military base of the southern Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes in the course of moving the border forward and consolidating Roman power relations during the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161) around 150/155 built in stone. The slightly shifted floor plan is perhaps due to device errors in the Gromae used . As it turned out during the 2004 excavations, the area in the examined area had apparently been cleared of shrubbery. This is indicated by unpaved and archaeologically unproductive fire sites. Stratigraphically directly above it could be observed the early Roman construction work during the construction of the camp. In a first step, the lower edge areas of the planned warehouse were partially terraced due to the steep terrain slope in order to facilitate the development. These levels were lowered over the course of many centuries and favored the state of preservation of the findings in their area. To the west of the north-west gate, the embankment, some over a meter high, consisted of the locally occurring Opalinus Clay . The excavators noticed both higher lying, brown weathered clay layers as well as those from deeper levels. This dreadful clay was used, for example, to excavate the fort trenches. Almost no finds come from this foundation horizon of the camp, but plate limestone was discovered that did not have to be on site and had to be brought in. In the form of rubble, they apparently got into the ground when the buildings were erected.

Enclosure

The fort wall, made of white Jura stone, is 1.7 meters wide in the foundation. Your rising masonry is still 1.4 meters thick. The four corner walls of the complex are rounded off in the shape of a playing card and each towered over by an attached tower. All four camp gates were designed with two lanes and each have two flanking gate towers. The north-western camp gate, here the Porta principalis sinistra , which was explored during the construction of the museum in 1964 , revealed that the two gate towers each had a rear, ground-level entrance 1 (west tower) and 1.1 meters (east tower) width and that the street was filled with limestone rubble was. The west tower was 4.9 meters wide, the dimensions of the east tower cannot be determined with certainty due to the poor state of preservation - only the southern rear wall was preserved. The width of the two gateways varies between 3.5 meters in the west and 4.2 meters in the east. The Porta praetoria , the main gate of a Roman camp, opens in Aalen to the northeast towards the valley of the Kocher. Its former location is now marked with paving stones set into the ground. The foundation area of the St. John's Church immediately in front of the gate, which has now been freed from plaster, shows Roman ashlar stones that were used as spoilers from demolished buildings. This was only discovered in 1973 during renovation work. The spolia material comes at least in part from the fort. For example, a tin cover with a rounded top from the fort wall was identified in the lowest foundation layer at today's level, which gives a visual and measurable picture of the original appearance of this building detail. Research assumes that an older church building, which could be found in place of today's church, is related to Alemannic finds that came out of the ground in 1979 about 100 meters north in the ruins of a large thermal bath. On the basis of coin finds in the late 3rd and 4th centuries in the vicus area, it was also said in the past that after the garrison was abandoned in Aalen in the time of the Limes fall in 259/260 AD, residents of the civilian settlement remained behind and were already there started demolishing the fort. According to this theory, the very first building in place of today's church was perhaps already built by these camp village residents.

In addition to the towers mentioned, the garrison has two intermediate towers on the pretorial and rear side and four intermediate towers on the long sides. The RLK was able to identify two circumferential pointed trenches as an obstacle to the approach. The archaeological work on the southeast wall in the late 20th century identified two more trenches there. Research therefore suspects that the fort was surrounded by a total of four moats. The innermost of these trenches was 4.8 meters wide and 1.4 meters deep.

Interior development

Streets

- Via principalis

During the investigations led by Planck on the seven-meter-wide Via principalis , which connected the north-west and south-east gates in Aalen, it was found that it had a covering of carefully gravel. Its substructure consisted of a wooden grate made of around 0.3 m wide boards, which had never been uncovered on the Limes, which was perhaps used for static reasons due to the soft Opalinus clay. Since the street from the Porta princialis sinistra to the staff building has to overcome a height difference of around four meters, it was deepened into the surface to compensate. This created an embankment of over one meter at its edges.

- Via sagularis

In 2004 a small part of the Via sagularis was uncovered in the area in front of the intermediate tower to the west of the northwest gate. As a ring road, the Via sagularis encloses the interior of most of the forts. However, the archaeologists were unable to capture the full width of this road, which was built after the underground had been leveled. The substructure consisted of gravel and stone layers up to 80 centimeters high. In its lowest position, the foundation consisted of coarse limestone and a large number of horse bones. Among other things, a round bronze fitting was discovered in this layer, which had fine millefiori inlays in a chessboard shape. Only in the immediate vicinity of the intermediate tower did the excavators discover a different foundation layer made of rubble, mainly limestone fragments and mortar. These splinters were created when cutting hand blocks for the masonry. Small fragments of tufa limestone that were also found indicate the manufacture of architectural parts. A folded bronze sheet with nail holes is worth mentioning as a single find from this area. The Romans used fist-sized pebbles and limestone quarries to secure the surface of the run, which were set and pounded. As already stated with Via principalis , this ground was finally covered with poured brook pebbles. In a shallow depression in the road, which may have formed a puddle in antiquity, a small purse was uncovered which contained four partly worn coins: a Flavian ace , possibly from the reign of Emperor Vespasian (69-79 AD). , a dupondius and a sesterce of the emperor Marc Aurel (161-180 AD) and a much less used denarius made in the east of the empire from the years of the emperor Severus Alexander (222-235 AD). The backfill of the gravel had to be renewed from time to time. In the older layer below the level of the coin there was still a once lost denarius of Emperor Caracalla (211–217 AD). Thus, the last new pebble of the Ringstrasse took place, at least in this area, in the years between 217 and 222. A canal about one meter wide and about 60 centimeters deep had been created between the via sagularis and the inner building. Its distance to the buildings was also around one meter. Archaeologists assume that this canal was once covered, for which there is no tangible evidence so far.

- Via vicenaria

During the excavations in 2004, a section of this cross street at the western corner of the Horreum from Via sagularis to Via vicenaria was also examined. A two-phase drainage channel, mostly filled with rubble, was found towards the Horreum. The gravel was still clearly preserved from the road surface itself. The structure of this street structure was much simpler than on the main camp routes. The basis of the Via Vicenaria was a thin layer of rubble, which was then graveled over. On the basis of clearly separable stone and gravel fillings, repair measures were demonstrated that had repeatedly become necessary in the course of long use. What was remarkable was the finding of a concentration of around 15 centimeters long carpenter's nails, which had withstood the passage of time in a hollow in the road. As it turned out, the position of these nails still indicated their former location in a completely bygone wooden structure. With or after the end of the fort, building rubble had collapsed at this point and was not removed again. As a result, these wooden beams rot in place. The rubble of the horreum had slipped in the area of the excavation in 2004 to the Via vicenaria , whereby the archaeologists were no longer able to separate the two layers from one another. As it turned out, there were many pre-crushed non-ferrous metal finds for the smelter, which had been set up in the Horreum nearby during the late period of the fort, under the stone of the storage building on the street floor.

Crew barracks

To the east of the Via principalis , in the Praetentura , parts of wooden crew barracks from the early construction phase were uncovered, overlaid by two large, younger pits with finds from the 2nd century that can be dated. These pits indicate buildings that were built there later. In one large fragments of an iron face helmet were uncovered, in the other not only the bones of an almost completely preserved, intact horse skeleton could be recovered, but also parts of a rare Millefiori glass bowl from the 3rd century. The likely male horse, undoubtedly an ala mount, lived about three and a half years old. It was 145 cm high at the withers and was of a slender but stocky nature. This find confirms with many others, especially from the mass grave of Fort Gellep , in which over 30 cavalry horses, some with their riders, have been buried, the average height of 1.40 meters.

Commercial buildings

- Horror

Besides the Principia , only two other stone buildings from the interior of the fort in the area of the Latera Praetorii , the central part of the camp, are known. One of these structures, which stretches along the edge of Via Principalis between the staff building and the north-west gate, could only be clearly identified during the 2004 excavations. Planck, who had already partially cut into the building, thought of a large magazine ( Horreum ) of the so-called courtyard type. Other considerations saw him as a hospital (Valetudinarium) .

The rectangular stone building bordering the Via principalis with its front had a total size of 60 × 26.5 meters and had a rectangular inner courtyard measuring 47.33 × 13.6 meters. The foundation on the south-west outer wall, which was 70 centimeters thick at the time of the excavation and was established in the Opalinus Clay , was stepped at intervals of around six meters due to the sloping terrain to the north-west. On its western corner, five brick layers of ashlar above the rolling could be identified, the lowest layer being made of up to 50 centimeters long rubble stones at all verifiable points of the building. All of these layers were part of the foundation. There was no evidence of the rising masonry, such as a wall recess. The deepest point of the structure was on the north corner. This was founded on a mighty, 90 × 80 × 20 centimeter large Lauchheim sand-lime stone base. The foundation of the wall surrounding the inner courtyard was much flatter. The excavator Scholz interpreted a stone layer that was only fragmentary and connected to these foundations as the remains of a former courtyard gravel. Evidently on three sides, north, west and east, the room corridors between the outer wall and the inner courtyard have an inner width of six meters (20 Roman feet). In the reconstructions, the excavator suggests this width for the unknown, southern flight of rooms. Originally, at least in the examined west corner, a wooden plank floor was installed, but it was removed in Roman times. From this floor there were still little bar graves arranged at right angles to the walls. It was also possible to see imprints from the support beams, which enabled air to circulate under the floorboards. Since the building rested on the first leveling layer of encased Opalinus Clay with numerous limestone quarries, it was probably built very early. No partitions could be found, which suggests that any room divisions were made of wood. Due to the lack of specific findings, the excavations also confirmed Planck's considerations that the building had a courtyard- type horreum in front of it. Typical of these buildings, which the Romans also used in the civil area, are rows of chambers that are grouped around a closed or one-sided open inner courtyard. This finding is so far unique at the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes forts and could be a special feature for camps of the Alae milliariae , who needed a particularly large feed depot especially for the horses. The lack of appropriate facilities, such as a water basin in the inner courtyard, the building's own water supply and latrines, speaks against a valetudinarium, which basically has a similar floor plan. In addition, for the excavator Scholz, the building found in Aalen was too big even for a force of a thousand men.

As already mentioned, at least part of the wooden floor was removed in the late period of the fort. The soldiers then set up a non-ferrous metal processing plant in the examined western corner in the Horreum . This is evidenced by several clear burns and scrap metal objects that were pre-shredded for melting. An almost mint fresh, antoninian of the Emperor Volusianus from the year 253, which comes from the workshop shift, chronicles this event. Most of the metals found came from disused cavalry equipment, including fragments of parade armor, but also from broken statues. The findings also included numerous cast iron droplets, melted parts and metal-containing slag. Everything indicates that there was only very provisional, short-term and primitive work there. In a rectangular pit measuring 0.9 × 1.3 meters near the western corner, further pre-shredded scrap metal remains were found, including, particularly noteworthy, bronze connecting elements of a rail armor , a stilus , nails and a sword strap holder. This conglomerate appears to have been housed in a bygone wooden box, as a conspicuously rectangular discoloration was observed under it. On the outer wall in the area of the western corner to Via Vicenaria , there were still remnants of a small stack of roof tiles, which also belonged to the late period. The circumstances under which this provisional fabrica worked during the last decade of the Raetian Limes cannot be determined. However, it can be confirmed that around 253 the walls of the horreum were still standing. The excavator rules out any post-Roman use. The cultural layer, which dates back to the Middle Ages or the modern era, just below the sward bears witness to the rummaging of the rubble in the storage facility. Several fragmented and weathered roof tiles were found in it. However, the amount found is not sufficient to draw conclusions about the roofing of this structure.

- Wooden commercial construction

The finding of a wooden building northwest of the Horreum, between Via vicenaria and Via quintana surprised the archaeologists in their research in 2004. Altogether, three large wooden construction phases could be distinguished in this section, in which three differently designed elongated barracks, some with fireplaces, are closed in one place different times. The final find report for this excavation section is still pending. However, Scholz expects a workshop at this point.

Findings and questions

In addition to the late rail armor, the excavators found over a dozen coarsely forged bullet tips in the excavation area in 2004, which were scattered throughout the most recent Roman layers. As a result of these discoveries, Scholz came up with new questions about the late phase and the demise of the camp. In his opinion, the rail armor could indicate a previously unknown late change of troops in the fort. He also considered assigning the projectile tips, some of which were distorted and bent, to a German attack that might have taken place in the crisis years 253/254, when Emperor Valerianus withdrew contingents from the Rhaetian army that were essential for the defense of the province. The Germans then exploited this sensitive weakening of the border troops for massive incursions into the province. This thesis is also supported by the findings from the vicus of the north-eastern border fort of Buch . Its camp village was destroyed in 254 AD by a fire, apparently also triggered by an attack by the Teutons. However, research was able to prove for the fort in the northeast of Buch that the Roman settlement continuity, even after the occupation had withdrawn, possibly lasted into the early 4th century.

Praetorium or another horreum

The second oblong, rectangular stone building was erected in the middle section of the camp between the Principia and the southeastern camp ring road. As could be determined during the RLK excavations, the orientation of the building did not quite follow the grid given by the main streets of the camp, but rather turned with its southern narrow side slightly out of this in a westerly direction. There is a large gap between the building and Via principalis dextra , the main street leading to the south-east from the fort, in which the building could easily have space again. The reason for this is unknown. Since there are plans to see part of the commander's house ( praetorium ) in the complex, which is divided into multiple sections , it was assumed that the other wings of this house were built in half-timbered construction and were therefore not recognized during the RLK excavations. Other opinions suggest that there is more horror in the massive building structure , as the RLK encountered large amounts of charred grain there. Since there have been no recent excavations so far, further statements about the building are speculation.

Headquarters building

In the same period as the barracks, a row of wooden posts in the area of the later vestibule on the Principia belongs , which can be interpreted as a possible, short-term, oldest roofing of the Via principalis . After only a few years this light roofing was put down for the construction of a mighty, massive wooden vestibule, which, as usual, sat astride the Via principalis . Its large, square, approximately 0.4 m wide oak beams were very well preserved in the Opalinus Clay. The Roman builders placed these girders in the ground on oak planks six to nine centimeters thick in order to distribute the weight pressure on the surface and prevent them from sinking into the ground. The dendrochronological examination of the wood material revealed a uniform felling date of 160 ± 10 AD. These vestibules, typical of forts of that time, served as representative multi-purpose rooms. In the area of the actual Principia, with its service and administration rooms arranged in a square around a rectangular inner courtyard 22 by 24 meters, no preceding wooden buildings could be identified. Due to the building inscription found here from the reign of Emperor Mark Aurel and his co-regent Lucius Verus , Géza Alföldy was able to clearly date its completion to the period from the end of AD 163 to the end of 164 AD. Accordingly, the wooden vestibule was created at the same time as the stone construction of the staff building. The date also overlaps with the palisade expansion phase of the Rhaetian Limes, which has also been documented dendrochronologically in other places. The construction of timbers on the provincial border of Germania superior and Raetia at the Kleindeinbach small fort was dated to the year 164 AD and in Schwabsberg , west of the Limestor Dalkingen , these palisade timbers can be assigned to the time around 165 AD. The circumferential rooms of the Principia , some of which are heated at the rear and which have changed over time, are around 10.6 meters wide. The researchers noticed that in this building, none of the usual armory (Armamentaria) has given. In the inner courtyard , in the area of its rear, eight-meter-wide entrance, a 5 × 5 meter large and around one meter deep wood-paneled cistern was uncovered, which at this misplaced place may only date from the Middle Ages. In the southern corner of the courtyard there was a 4 × 4 meter rectangular foundation on which an apse closed to the southeast was bricked. Research believes that there was a pool of water here, behind which perhaps a statue of a spring nymph stood in the apse . In the eastern corner of the courtyard, the well-preserved mortised wooden casing was uncovered with a well around eleven meters deep. The investigation revealed a felling date of 179 ± 10 AD. The well, however, contained only a few finds.

The five-meter-deep apse of the flag sanctuary (Aedes principiorum) , which was subsequently massively reinforced, arches from the middle of the rear wall of the staff building . Here it becomes clear that these Principia were a mighty representative building with three or four access levels. The design of the sanctuary with apses can be observed in the castles from the middle of the 2nd century. The space in front of the apse, in which the standards of the unit stood, had a clear width of 7.5 × 7.5 meters. Planck assumes that the front area of this room was reserved for a staircase to the top floors. In the partially basement sanctuary with a flag, there was a 4.5 m × 7.5 m large and around 1.8 m high cellar (aerarium) for the troop coffers, which was probably accessible through a ladder. Wooden beams and planks served as the cellar ceiling. Among other things, 32 silver coins as well as gold and silver jewelry were found in the rubble of the cellar. In addition, in addition to standard militaria, a large number of bronze fragments were found that belonged to an imperial tank statue from the first half of the 3rd century AD. The ancient screed was preserved in the apse of the sanctuary, which is why clear traces of a round stone bench that had once been installed could be found. The 1984 discovery of an aureus from the reign of Emperor Vespasian (69–79) in the screed floor is interpreted as a construction sacrifice. In one of the inscriptions found, the flag shrine is referred to as the Capitolium . At the time, this was the first time that research was able to provide a reliable designation for this area of the staff building. The inscription is one of the most important finds from the cavalry fort. Jupiter and the Capitoline Triassic were probably worshiped in the Aalen sanctuary . For this purpose, the RLK had already recovered a formerly gilded bronze sheet with the image of the Dolichenic gods ( Iupiter Dolichenus , Iuno Regina , Minerva ) from the aerarium in 1895 , which is dated to the late 2nd / early 3rd century. A dedicatory inscription by Decurios Titus Vitalius Adventus of Ala II Flavia for Iupiter Dolichenus for Iupiter Dolichenus, which was reused in 1973 during renovation work on the St. John's Church located directly in front of the former Porta praetoria , could also come from the Capitolium . In 1986, brick stamps of Legio VIII Augusta from Strasbourg and Ala II Flavia were uncovered in the southernmost room of the rear building, which can be entered directly from the inner corridor of the staff building and which could be heated . After almost 44 years, the wooden vestibule was replaced by a representative, richly structured and massive stone structure measuring around 65 × 21 meters. The three entrances to the Via principalis and Via praetoria with outward-facing tongue walls make the claim and expression of power of Rome clear through a particularly impressive example of Roman representational architecture in the border area. The remains of three building inscriptions were recovered in the area of this hall. Alföldy dated all three to the year 208, the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211) and his two sons Caracalla and Geta . The year the new vestibule was built and the renovation or conversion of the Principia are therefore well known. One of the inscriptions mentions that the Ala II Flavia restored some buildings under the command of an imperial legate . The name Principia is mentioned on two building inscriptions from the year 208 (see below) . In one of the rooms to the right of the Capitolium , the Keupers sandstone head, twelve centimeters tall, of a statuette of the Genius Alae , the guardian of the cavalry troops, was found in October 1895 and wore a wall crown (Corona muralis) .

A denarius from the time of Emperor Aemilianus , dated to his first year of reign 253 and minted in Antioch , formed the final coin from the fort area after the excavations in 1978–1986 . In addition to clear signs of fire on the buildings, it indicates the end of the garrison and the camp village. Also in this year, but minted a little earlier, belongs the latest coin find that emerged from the ground during the 2004 excavation on the magazine building. This was an Antoninian of the Emperor Volusianus , who died in 253.

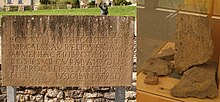

Building inscriptions

The oldest building inscription from the years 163/164 under the reign of Emperor Mark Aurel reads:

[Imp (eratori) Caes (ari)] M (arco) Aur [elio Anto]

[nino Aug (usto)] p (ontifici) m (aximo) t [ribunicia]

[pot (estate) XVIII] imp (eratori) II [co (n) s (uli) III p (atri) p (atriae) et]

[Imp (eratori) Caes (ari) L (ucio)] Aureli [o Vero Aug (usto)]

[Armenia] c (o) trib (unicia) pot (estate) III [I imp (eratori) II]

[co (n) s (uli) II su] b cura Bai P [uden]

[tis proc (uratoris) per ala] m II F [l (aviam) | (milliariam) p (iam) f (idelem)]

[fecit?…] ius Lo [lli] an [us? praef (ectus)]

Translation: “For Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, the high priest, when he held tribunician power for the 18th time, Emperor for the 2nd time, Consul for the 3rd time, the father of the fatherland and the Emperor Caesar Lucius Aurelius Verus Augustus, the Armenian, when he held tribunician power for the fourth time, imperator for the second time, consul for the second time, the Principia were under the supervision of the provincial governor Baius Pudens of the Ala II Flavia milliaria, the faithful and reliable under the Supreme command of the commander ... ius Lollianus established. "

Another building inscription from AD 208 under Septimus Severus:

[I] mp (eratori) [C] aes (ari) [L (ucio)] Sept (imio) Severo P [io Pe] rt [inaci]

[A] ug (usto) [Ar] ab (ico) Adiab ( enico), P [ar] t (hico) max (imo), [pontif (ici) max (imo)],

[t] rib (unicia) [po] t (estate) XVI, im [p (eratori) XII , co (n) s (uli) III, proco (n) s (uli), p (atri) p (atriae), et]

Imp (eratori) [Ca] es (ari) M (arco) [Aurelio Antonino Pio Fel (ici)]

Au [g (usto), tri] b (unicia) p [ot (estate) XI, co (n) s (uli)] III, im [p (eratori) II, proco (n) s (uli), et]

[[P (ublio) S [eptimio Getae] Caes (ari)]], [al (a) II Fl (avia) | (milliaria) p (ia) f (idelis)],

[cui praeest ---] ius [---, sub cura]

[--- Acutiani], c (larissimi) [v (iri), le] g (ati) Au [gg (ustorum) pro praet (ore)]

[ provinciae Raet] iae, [pr] in [cipia restituit]

Translation: "For Emperor Lucius Septimius Severus, the pious, persistent, the sublime, the Arab, Adiabenic, the greatest Parthian, the high priest, when he held tribunician power for the 16th time, was imperator for the 12th time, and was consul for the 3rd Time, the proconsul, father of the fatherland and the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius, the happy, sublime, when he held tribunician power for the 11th time, consul for the 3rd time. was, Emperor for the 2nd time, the proconsul and Publius Septimius Geta, Caesar had the Ala II Flavia pia fidelis milliaria restored under the command ... ius under the supervision of Acutianus, governor of the province of Raetia. "

The following building inscription is also known from the year 208:

[Imp (eratori) Caes (ari) L (ucio) Sept (imio) Severo Pio Pertinaci]

[Aug (usto), Arab (ico), Adiab (enico), Part (hico) max (imo), pont (ifici) max (imo)],

[trib (unicia) pot (estate) XVI, co (n) s (uli) III, i] mp (eratori) XII, [proco (n) s (uli), p (atri) p (atriae), et]

Imp (eratori) Caes (ari) M (arco) [Aurel (io) Ant] on [ino Pio Fel (ici)]

Aug (usto), trib (unicia) p [ot (estate) XI , co (n) s (uli) III, imp (eratori) II, proco (n) s (uli), et]

[[P (ublio) S [e] pt (imio) [Get] ae Cae [s ( ari)]] al (a) II Fl (avia) milliaria) p (ia) f (idelis) C] ap [i-]

tol [i] um cum pri [ncipiis vetust] at [e]

conlap [sis restituit sub cura ---]

A [cu] tian [i, c (larissimi) v (iri), leg (ati) Augg (ustorum) pro praet (ore)]

Translation: “For Emperor Lucius Septimius Severus, the pious, the persistent, the sublime, the Arab, the Aadiabenic, the greatest Parthian, the high priest, when he held the tribunician power for the 16th time, was consul for the 3rd time, Emperor for the 12th time, the proconsul, the father of the fatherland and the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, the pious, happy, the sublime, when he held tribunician power for the 11th time, was consul for the 3rd time and emperor for the 2nd time , to the proconsul and Publius Septimius Geta Caesar, the Ala II milliaria, the Reliable and Faithful, restored the flag shrine and the principia, which had decayed through age, under the supervision of the governor Acutianus. "

Karlheinz Dietz made a critical statement in 1993 on this attempt to reconstruct the text in the building inscription. In his opinion, the passage capitolium cum principiis (the flag sanctuary and the staff building) has been misinterpreted. In his opinion, the correct reading would be praetorium cum principiis (the commandant's house and the staff building) , since the flag sanctuary and the principia formed a structural unit and therefore would not have been mentioned separately in a building inscription. Dietz also assumes that, among other things, the inscription AE | 1989 | 583 found in the Principia was also created in the year 208 and reconstructs a person from the governor Scribonius mentioned in fragments and the name of the governor Acutianus, which is fragmentarily legible from the above-mentioned building inscriptions : Scribonius Acutianus.

Vicus, thermal baths and burial ground

The vicus , the camp village that developed rapidly around most of the forts, initially offered the respective garrison in its early phases that additional infrastructure that supplemented the military and private life of the soldiers. Among other things, the families of the stationed lived there, offering innkeepers, craftsmen, traders and farmers opportunities to spend their free time and to purchase regional and national goods. Often times, the camp villages developed a dynamic life of their own, independent of the fort operation. Quite a few residents achieved some prosperity, especially through the trade in long-distance goods, and could in some cases afford high-quality grave monuments. In the villages of the Limes region, there are not only the typical wooden long houses along the arterial roads of the fort, but also elaborate stone buildings with hypocausted rooms, which in their overall structure could sometimes take on a city-like character.

The vicus of Aalen can no longer be explored in large areas due to the development of the 20th century. In many cases, accidental finds were made and emergency excavations were scheduled. Therefore, only the approximate built-up area can be determined. Its extent in the northeast, east and southeast over the eel and up to the Kocher is certain. One of the most important stone buildings of the civil settlement emerged from the ground in 1882 exactly in front of the pointed trenches in the northeast corner of the fort. It also disappeared through the later urban development. Almost all of the rooms in the elongated, large building turned in a north-westerly direction were equipped with hypocaust heating. It was referred to as a fort bath ( Balineum ) by its excavators , but this is now in question because there are no typical features. In particular, the two tower-like rectangular additions that flanked the south-eastern front wall raised doubts. In the rubble of the house, stamps of the Ala II Flavia were discovered, which show that the building was built under the leadership of the Aalen garrison and was therefore certainly used in some form by the military. Another larger building complex was uncovered in parts in 1897, south-east of the hypocausted building, 60 meters in front of the praetorial front of the fort, when the mortuary for the city cemetery was being built. The walls of the house were at right angles to each other and, like a chessboard, formed rectangular rooms of roughly the same size. On the western wall, which could perhaps be referred to as an outer wall, an apse arched from one of these rooms. Steimle speculated that these could have been the remains of a residential building. Exactly in the axis of this structure, but 130 meters away from the Praetorial Front, another large building in the camp village was finally destroyed in 1980 by the construction of a residential house, which was previously partially explored. Particularly because of a 10 × 10 meter hypocaust room that had been heated from the south-east, the consideration arose to address these remains as part of the fort bath. The fact that large areas of the building had already been made unrecognizable by the foundations of the modern buildings before the excavation at that time caused great difficulties in the evaluation. Planck spoke out in favor of addressing the building, which was uncovered in 1897, as a very large thermal spa complex when it was discovered in 1980. When they were barracked in Heidenheim (Aquileia) , Ala II Flavia had a similarly large bathing facility available, which was excavated in 1980 and then preserved. In 1938, further information on the vicus could be gained on the Neue Breite corridor on an area of around 150 meters . In addition to building structures from the 2nd and 3rd centuries, seven wells with wooden formwork were particularly interesting for research. So far, no civil settlement structure in Aalen has been saved for posterity.

Aalen's fire burial ground is traditionally located on the Krähenbühl corridor on Aalener Burgberg. In 1925, a 40-square-meter cremation site from the 2nd and 3rd centuries was documented and the foundations of a large grave complex were found around 90 meters east of it. In the past, this statement was also represented by Philipp Filtzinger and Dieter Planck in various publications. However, there are voices who suspect a previously unknown Villa Rustica in the area of the burn marks . Martin Kemkes , scientific director of the Limes Museum in Aalen, also considered whether to see the remains of a public monument in the findings previously interpreted as a tomb. The foundations, excavated in 1925, consisted of two square, approximately 2 × 2 meter large stone plinth-like bases, which were symmetrically arranged at a distance of approximately 3.3 meters. In the area between the plinths, the excavators found a neatly executed paving with mostly oblong-rectangular stones up to a meter long. This pavement continued for around 1.5 meters in one direction.

Water supply

The three wells found in the Aalen Latera praetorii (middle section) and in the parts of the Praetentura near the Via principalis can only have covered a small part of the water required for a troop of around 1000 riders, if only the water requirement of a horse with around 20 to 50 liters, based on this. Marcus Junkelmann calculated between 1200 and well over 2000 horses for an Ala milliaria . Even if one assumes that there were further fresh water points in the unexplored storage areas, it is still unclear how the fort, located on a plateau, could be supplied with the required amounts of water. The eel was certainly important for this.

Troops and officers

The only troops attested to for the fort, the approximately 1000-strong mounted auxiliary unit Ala II Flavia milliaria , probably arose under the Flavians. An earlier explanation of its origin assumed that this regiment was formed in the Rhenish area after the Bataverkrieg 69/70 AD. At that time, the Rhine Army was reorganized under the rule of Emperor Vespasian (69-79) from remnants of older units and together with the Ala I Flavia Gemina . While the latter was probably relocated from the Mogontiacum area between 83 and 122 AD to the 5.2 hectare fort Heddernheim , the Ala II Flavia milliaria is also supposed to come from Mainz as early as 83 AD in the Wetterau Limes area to the fort Okarben have come. The more recent research assumes, however, that the Ala II Flavia milliaria was already parked under Vespasian immediately after Raetia ( Raetia ). In the past, the Ala II Flavia milliaria was equated with the Ala II Flavia gemina mentioned on Upper Germanic military diplomas from 74 and 82 AD , which may have led to confusion. It is possible that the Ala II Flavia milliaria was already found in Raetia from at least 77/78 AD . In the Günzburg (Guntia) fort there was a fragment of a building inscription from those years that the Praefectus (commandant) of an Ala milliaria had put up. However, the name of the unit was not retained. Since the Roman Empire didn't have more than seven or nine Alae milliariae , there are few choices as to which troops are eligible. In addition, a brick temple was found near the Guntia fort , which perhaps names an Ala II Flavia . A localization of the Ala to Guntia would fit into the historical sequence of border transfers from the Danube to the north (Günzburg, Heidenheim, Aalen) .

When Lucius Antonius Saturninus , governor of the province of Germania superior (Upper Germany), rose against Emperor Domitian (81-96) in January 89 AD and rose from his two legions stationed there, the Legio XIV Gemina and the Legio XXI Rapax , the Emperor made a proclamation, the presented Ala II Flavia on the side of Domitian, what do you after the suppression of the Upper German uprising by the governor of Germania inferior (Lower Germania), Aulus Bucius Lappius Maximus , the honorific epithet pia fidelis Domitiana ( "the Domitian, loyal and reliable ”). With the Damnatio memoriae , the state-decreed erasure of the memory of Emperor Domitian, the "Domitiana" is taken back again. For the first time in the province of Raetia the II Flavia Pia Fidelis Milliaria is mentioned by the Weißenburg military diploma of June 30th, 107 AD. Its location at the time can be found in the 5.28 hectare large and 20 kilometers south of Heidenheim Fort , which was built around 90 AD - probably already by the Flavian Ala II . A fragment of an equestrian grave of this troop was found there. With the relocation of the Limes to the Remstal area, the Ala II Flavia milliaria also got its new and most likely last location. She built the Aalen castle. In addition to the stone epigraphic evidence of the troops found there, it is still mentioned in several Rhaetian military diplomas up to AD 166. In 222 the troops were given the honorary title of "Alexandriana" by Emperor Severus Alexander (222–235 AD), but with the death and the Damnatio memoriae of this ruler, they lost it again. An ala milliaria represented a significant potential for struggle and power.

The Alae milliariae were probably not created before the Flavian period (69–96 AD). They were under the command of a Praefectus and were divided into 24 Turmae (squadrons), each led by a Decurio (Rittmeister). The rank of Praefectus could only rarely be awarded due to the few Alae milliariae and was not only in extremely high esteem, but was, as individual traditional careers show, a stepping stone to the highest offices. In rank the commander of an ala milliaria stood above the leaders of other auxiliary troops . It was assumed that the Praefectus von Aalen was also deputy governor of the province of Raetia . At least the entire western part of the Rhaetian Limes - from Fort Schirenhof to Halheim - seems to have been subordinate to him.

Probably the most important evidence of a rider of the Ala II Flavia milliaria was discovered in Rome and dates from the 2nd century. He was given the great honor of being transferred from Raetia to the Imperial Guard. Today the tombstone is in Castel Gandolfo .

Diis Manibus

T [itus] Flavius Qui [n] tinusv

Eq [ues] sing [ularis] Aug [usti], lectus

ex Exercitu Raetico

ex Ala Flavia pia fideli

miliaria stipendio

rum sex vixit annos

XXXVI Publicus Crescens

et Claudius Paternus

heredes benuntemerenti

posuer

Translation: "The gods of the dead, Titus Flavius Quintinus, imperial guard rider, selected from the Rhaetian army, from the Ala Flavia pia fidelis miliaria, served six years, lived 36. His heirs Publicus Crescens and Claudius Paternus set this stone for the well-deserved."

The career of the rider Secundus, son of Sabinus, has a more common résumé. He remained in the rank of simple Eques until he left the army in 153 AD . With the imperial constitution documented in a military diploma, his marriage to Secunda, daughter of Borus, was legally recognized. Since this diploma was found in Castra Regina (Regensburg), Secundus will probably have retired there.

Through the fragment of a cavalry object, which was planned in the late period of the fort with further scrap metal for melting down in the western corner of the great horreum of the court type north of the Principia , both the name of a rider and an officer in the rank of squadron leader ( decurio ) preserved.

T [urma] Firman [i] Conces [s] i

Translation: "Property of Concessus from the squadron of Firmanus."

Only fragments of the names of the commanders (Praefecti) have survived in Aalen through building inscriptions. Thus, the researchers have identified a ... jus Lollianus (163/164 n. Chr.), A Vetus (late 2nd century / 208?), A ... jus (208 n. Chr.) And L (ucius) Vi ... . A complete commander's name has been preserved for the year 153 AD through the aforementioned military diploma from Regensburg: Tiberius Claudius Rufus . After his command in Aalen he was transferred to Poetovio ( Ptuj ) in the province of Pannonia superior as Procurator Augusti (financial administrator) with an annual salary of 100,000 sesterces, as the tombstone found there shows.

A commander from the knighthood, stationed in Aalen around 160 AD, whose name has also not been preserved, mentions his entire career on an inscription found in Segermes , south of Tunis . He was initially a tribune of the Cohors XX ... voluntariorum , a 500-man infantry unit, and was then transferred to the Legio XIII Gemina in Romania as a tribunus angusticlavius (knightly staff officer) . He then took over as commander of the Ala Vettonum , a 500-man cavalry regiment, and then as Praefectus alae miliariae the Aalen troops. The following command led him as a road commissioner (curator viae Pedanae) in the area east of Rome and then as a procurator to Poetovio in Pannonia superior . At the end of his career he became Procurator Augustorum regionis , administrator of the imperial property, at Hadrumetum ( Sousse ) in what is now Tunisia.

The last example of a career as a commander is a procurator whose name has also not been passed down. His tombstone was discovered in Ostia Antica . British historian and archaeologist Eric Birley noted that this man's ministry began with leading the Cohors I Flavia Musulamiorum equitata in Mauretania Caesariensis . The next stop was the Cohors II Hispanorum miliaria equitata in the same province , followed by the Ala Sabiana in Britain, before joining the Ala II Flavia m. came to Raetia.

- Commanders of the Ala II Flavia milliaria

| Surname | rank | Time position | comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiberius Claudius Rufus | Praefectus | 153 | He then became the financial administrator of the Pannonia superior province in Ptuj, where he also died. |

| ? | Praefectus | around 160 | His fully preserved career led via Romania to Aalen, Rome, Slovenia and Tunisia, where he died as an imperial estate administrator. |

| ... ius Lollianus | Praefectus | 163/164 | On the fragment of the inscription, to which the prefect's name belongs, the provincial governor Sextus Baius Pudens is mentioned. |

| Vetus | Praefectus | late 2nd century / 208 (?) | The governor Scribonius is mentioned on the fragment of the inscription to which the prefect's name belongs. |

| ... ius | Praefectus | 208 | On the fragment of the inscription to which the prefect's name belongs, the governor Acutianus is mentioned. |

| ? | Praefectus | His fully preserved career began in Mauritania and passed through Britain to Aalen. He died as a state official in charge of the grain supply (procurator Ostiae ad annonam) in Ostia Antica. | |

| L (ucius) Vi ... | Praefectus |

Found good

Militaria

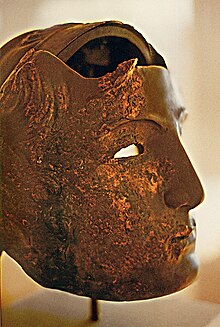

An important militaria find is the heavily fragmented, but almost complete masked helmet of the Alexander type that was recovered in 1978 when the Limes Museum was extended between the staff building and the Porta principalis sinistra . The 24.5 cm high and 21.5 cm wide iron helmet from the 2nd / 3rd centuries. Century was restored in the Roman-Germanic Central Museum in Mainz and is exhibited in the Limes Museum. (Junkelmann 1996, catalog no. O 98) Research assumes that the face helmets of the Alexander type worn by the Roman cavalry were last shaped in the Hadrianic era. The earliest piece to date is said to have been found together with Roman infantry clothing in a cave on Mount Hebron and can be dated to the time of the Bar Kochba uprising (132 to 135 AD). Typical of this Hellenistic helmet mask, which has developed from a masculine-feminine mixed type, are among other things a small mouth, a straight nose, long sideburns and an almost baroque hairstyle with "Alexander curls". Masked helmets of this time were probably not worn in combat, but only for parades and exhibition fights, in which the Roman cavalry showed their skills. Flavius Arrianus recorded the course of such an exhibition match in his equestrian tract published in AD 136.

Shields were part of the defensive armament of the soldiers. Among other things, an undecorated, heavily damaged round bronze shield hump from the 2nd / 3rd century is in Aalen. Century preserved.

Various shaped iron projectile points also came out of the ground, which belonged to javelins ( Iacula ) and light throwing machines, as they had been used by the Roman infantry.

In the basement of the flag shrine, two objects of military historical importance were found that must have belonged to the standards of the unit. These include a 4.3 cm high seated bronze eagle with attached wings and a silver, gold-plated heart-shaped pendant. Both pieces will be on the 2nd / 3rd assigned to the AD century.

During the excavations at a late secondary non-ferrous metal melt in the Horreum of the court type, fragments of parade armor , a sword sling holder and bronze connecting elements of a rail armor ( Lorica Segmentata ) were found, which the excavator Markus Scholz ascribed to the type Alba Iulia. The complete appearance of this type is only known from a fragmented relief from Alba Iulia in Dacia , which is mostly ascribed to the 3rd century. It shows an infantryman with a rectangular legionary shield (scutum) , who carries an armor made of four wide metal rails that horizontally cover the body. There is scale armor around the neck and shoulders, which is closed with a two-part chest striking plate. The sword arm with the long sword, the spathe , is also protected by metal rails.

In 1981 a fragment of a military diploma was discovered between wooden barracks on the northern edge of the Retentura , which dates from 140 to 186 AD. Another fragment was recovered in 1986. Both pieces do not provide any more detailed information about the stationing of troops, commanders and discharged soldiers.

brick

In addition to the inscriptions, building bricks stamped with AL (a) II FL (avia) , which were first discovered during the excavations by Paulus the Younger and Mayer in 1882, confirm the presence of the Ala II Flavia milliaria . The discovery of another stamp made by Bauer earlier, this time from Leg (io) VIII Aug (usta) in Argentoratum ( Strasbourg ), cannot be explained beyond doubt to this day.

Well finds

Seven of the excavations in the vicus area are known to be up to eight meters deep, wood-paneled wells that were discovered in 1938 in the "Neue Breite" corridor. From "Brunnen 1" a single-handle jug became known, which with its inscription Decoratus turma A (?) Pris , named the name of a rider and a Decurios of Ala II Flavia milliaria : "Decoratus, owner of the jug from the squadron of Priscus".

Monument protection

The Aalen Fort and the aforementioned ground monuments have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage as a section of the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes since 2005 . In addition, the facilities are cultural monuments according to the Monument Protection Act of the State of Baden-Württemberg (DSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

General

- Dieter Planck : Aalen (AA) - fort for 1000 riders. In: D. Planck (Ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Roman sites from Aalen to Zwiefalten. Theiss, Stuttgart, 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 , pp. 9-18.

- Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd completely revised edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 .

- Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer , Andreas Thiel : The Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 .

- Heinrich Steimle : Aalen fort. In: Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey (Hrsg.): The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roemerreiches B VI No. 66 (1904).

Individual studies

- Karl Heinz Dietz: The renewal of the Limes Fort Aalen from AD 208. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica. 25, 1993, pp. 243-252.

- Hans-Heinz Hartmann: Terra sigillata from the staff building of the Aalen Fort. In: Find reports Baden-Württemberg. 20, 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1279-1 , pp. 667-705.

- Martin Kemkes , Markus Scholz : The Roman fort Aalen. UNESCO world heritage. Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2057-5 .

- Martin Kemkes: The fort vicus of Aalen. In: Vera Rupp , Heide Birley (Hrsg.): Country life in Roman Germany. Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2573-0 , pp. 82-85.

- Martin Kemkes, Markus Scholz: The Roman fort Aalen. Research and reconstruction of the largest equestrian fort on the UNESCO World Heritage Site Limes. Theiss, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8062-2057-3 .

- Rüdiger Krause : For the water supply of the Reiterkastell in Aalen, Ostalbkreis. In: Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 1999. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1469-7 , pp. 91-93.

- Stefan F. Pfahl : Golden times on the Limes. Rhaetian coin-building victims from Aalen and Oberstimm . In: Der Limes 1 (2014), pp. 32–36.

- Gabriele Seitz: Military diploma fragments from Rainau book and Aalen. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. 7, 1982, p. 317 ff., Doi: 10.11588 / fbbw.1982.0.26770 .

- Markus Scholz : Two commercial buildings in the Aalen Limes Fort. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , pp. 107-121. (= 3rd specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission on February 17th / 18th, 2005 in Weißenburg in Bavaria)

- Dieter Planck, Philipp Filtzinger : Aalen (AA) - Alenkastell for 1000 horsemen / Roman stones in the masonry of the St. Johannis Church / Limes Museum. In: Ph. Filtzinger (Ed.): The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. 3. Edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , pp. 203-211.

Web links

- Aalen Fort on the website of the German Limes Commission

- Model of the fort in the Limes Museum in Aalen

- Digital archeology Limes Fort Aalen with camp village

- Digital archeology principia

- Digital archeology vestibule of the Principia (exterior view)

- Digital archeology vestibule of the Principia (interior view)

- Digital archeology Inner courtyard of the staff building with central altar and nymphaeum

- Digital archeology View into a barracks alley

- Digital archeology arcade of a barracks barracks

- Digital archeology View into the fort vicus

- Digital archeology equestrian barracks

- Digital archeology Tabularium (writing room)

- Digital archeology Via Principalis with fabrica (workshops) and Porta Principalis sinistra (west gate)

- Digital archeology barracks close-up view (click numbering)

Remarks

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger , Dieter Planck, Bernhard Cämmerer: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-8062-0133-1 , p. 203.

- ↑ a b Markus Scholz : Two commercial buildings in the Limes Fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 109.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 13.

- ^ Konrad Miller: The Roman castles in Württemberg. Weise, Stuttgart 1892, p. 35.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger, Dieter Planck, Bernhard Cämmerer: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-8062-0133-1 , p. 201.

- ↑ a b Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Limes Fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 107.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle , von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 54.

- ↑ Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Limes fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , pp. 108-109.

- ↑ Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Limes fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 108.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger: Limes Museum Aalen. 2nd Edition. Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, p. 27.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger: Limes Museum Aalen. Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of south-west Germany (writings of the Limes Museum Aalen) 7, Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, p. 18.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd completely revised edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 125.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger: Limes Museum Aalen. Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of south-west Germany (writings of the Limes Museum Aalen) 7, Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, pp. 20, 24.

- ↑ a b c Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome. Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 89.

- ↑ a b c Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Limes Fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 110.

- ↑ a b c d Markus Scholz: Two farm buildings in the Limes fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes , Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 114.

- ↑ a b c d Markus Scholz: Two farm buildings in the Limes fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 111.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann : The Roman rider, Part I . von Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1006-4 , p. 32 ff.

- ^ Marcus Junkelmann : The riders of Rome , Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 92.

- ↑ a b c d e f Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Limes fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes , Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 113.

- ↑ a b Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Limes Fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes , Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 112.

- ↑ Markus Scholz: Two commercial buildings in the Limes fort Aalen. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 119.

- ^ Bernhard Albert Greiner: The fort vicus of Rainau book: History of settlement and correction of the dendrochronological data. In: Ludwig Wamser, Bernd Steidl: New research on Roman settlement between the Upper Rhine and Enns . Greiner, Remshalden-Grunbach 2002, ISBN 3-935383-09-6 , p. 85.

- ↑ Kastell book at 48 ° 54 '34.98 " N , 10 ° 8' 42.56" O .

- ^ Bernhard Albert Greiner: The fort vicus of Rainau book: History of settlement and correction of the dendrochronological data. In: Ludwig Wamser, Bernd Steidl: New research on Roman settlement between the Upper Rhine and Enns . Greiner, Remshalden-Grunbach 2002, ISBN 3-935383-09-6 , pp. 85, 88.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle , von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 310.

- ↑ Bernd Becker: Felling dates for Roman construction timbers based on a 2350 year old South German oak tree ring chronology. In: Find reports from Baden Württemberg. Volume 6. Theiss, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-8062-1252-X , pp. 369-386, doi: 10.11588 / fbbw.1981.0.26390 .

- ^ Wolfgang Czysz , Lothar Bakker: The Romans in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1058-6 , p. 123.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 152.

- ↑ Martin Kemkes : The image of the emperor on the border - A new large bronze fragment from the Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 144.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger: Limes Museum Aalen. 2nd Edition. Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, pp. 44, 45.

- ↑ a b Epigraphic Database Heidelberg ; AE 1986, 528 .

- ↑ a b Epigraphic Database Heidelberg ; AE 1989, 580 .

- ^ Epigraphic database Heidelberg AE 1989, 581 .

- ↑ a b AE 1989, 583

- ^ Karl Heinz Dietz: The renewal of the Limes fort Aalen from AD 208. In: Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica 25, 1993. (1993), pp. 243-252.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger: Limes Museum Aalen. 2nd Edition. Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, p. 153.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd completely revised edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 126.

- ↑ Martin Kemkes: The image of the emperor on the border - A new large bronze fragment from the Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes. Volume 3. Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 151.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome. Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 97 ff.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome. Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 110.

- ↑ Werner Eck , Andreas Pangerl: Titus Flavius Norbanus, "Praefectus praetorio" Domitians, as governor of Rhaetia in a new military diploma. In: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 163, 2007, pp. 239-251; here: pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Elmar Schwertheim: The monuments of oriental deities in Roman Germany. Brill, Leiden 1974, p. 271.

- ^ Karl Viktor Decker , Wolfgang Selzer : Mogontiacum: Mainz from the time of Augustus to the end of Roman rule. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World . II, 5th volume, 1st half volume. de Gruyter, Berlin 1976, p. 536.

- ^ Max Spindler, Andreas Kraus (Ed.): Handbook of Bavarian History. 3rd volume, 2nd part volume. Beck, Munich 1995, p. 56.

- ^ A b Egon Schallmayer : The Limes - History of a Border . Beck, Munich 2006, p. 108.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome. Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 84 f.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle , von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 32 f.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome. Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 83.

- ↑ CIL 6,3255

- ↑ a b CIL 16, 101 .

- ↑ a b Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome. Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 91.

- ^ AE 1989, 584

- ↑ CIL 3, 4046 .

- ↑ CIL 8, 23068 .

- ↑ a b Marcus Junkelmann: The riders of Rome. Part II, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 , p. 96.

- ↑ CIL 14, 4467 .

- ^ Richard Neudecker, Paul Zanker: Lebenswelten. Pictures and rooms in the Roman city of the imperial era. Volume 16 of the series Palilia, Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89500-515-0 , p. 76.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Riders like statues from Erz. Von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1819-7 , pp. 34, 94.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Riders like statues from Erz. Von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1819-7 , p. 26 ff., 88.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann : The riders of Rome. Part III. von Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1288-1 , p. 188.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann : The riders of Rome. Part III. von Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1288-1 , p. 136.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger : Limes Museum Aalen. 2nd Edition. Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, p. 44.