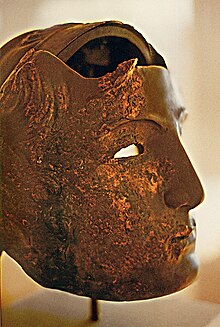

Mask helmet

Masked helmets are mostly military or warlike headgear, which, similar to the high medieval helmets, enclose the entire head of the wearer. In masked helmets, human faces of both sexes are reproduced in idealizing, sometimes alienating anthropomorphic shapes or elements, and through openings usually made in the nose, eyes and mouth area, the helmet wearer can act in a more or less restricted manner. The closure options and the attachment of the mask part are varied with this type of helmet.

Early forms

One of the oldest helmets with anthropomorphic features was discovered in the tomb of the Sumerian prince Mes-kalam-dug in Ur and can be traced back to around 2600 BC. To be dated. The early piece, made of gold, has a dome that reproduces the hair very finely and has ears carefully designed according to nature. Research estimates this helmet as a representational or ceremonial object. In later times there were numerous findings which, in the first place, also cannot yet be addressed as real masked helmets. So in Illyrian and Macedonian graves from the 6th century. The dead found there wore helmets of the Illyrian style and had face-like masks made of thin gold sheets in front of their faces, which had no real connection with the helmets, but had been placed on the deceased afterwards. The fact that the masks lacked any openings for the sensory organs was also indicative of this context. A type of helmet originates from the Hellenistic period, the calotte of which takes up the shape of the Phrygian hat that characterized the ancient Orient . Instead of a mask in front of it, the two cheek flaps of this type are very expansive and work over the face to close. Some specimens have anatomically developed structures such as beards and lips. The eye area and the nose are exposed in this helmet, which is known as " Phrygian " or " Thracian ".

Antiquity

A weapon frieze from the Athena shrine in Pergamon is of particular importance for the development of the later “real” masked helmet . This shows that the Hellenistic military tradition of the early 2nd century BC. BC could fall back on a fully trained mask helmet of the classic type. The mask helmet shown there, of which there is no equivalent in the finds, initially shows a type of helmet with a forehead visor known in Hellenistic areas. In addition, he has a corresponding, full-bearded mask, which, like the ancient statues, reproduces the human face in an idealizing-realistic way. This representation is the oldest on which an actual mask helmet can be seen. Since no links between the early anthropomorphic helmets and the Hellenistic masked helmets up to the Roman period have been proven archaeologically , science relies on theses which, however, do not in themselves constitute evidence.

The following statements are up for discussion today:

- Oriental thesis . An important advocate of this theory was Hubertus von Gall (1935–2018), speaker at the German Archaeological Institute in Tehran. Representations of masks at the great temple of Hatra in Iran show similarities to a mask helmet from Homs in Syria , which is dated to the early 1st century AD. This helmet is a variant of the Roman type Nijmegen-Kops Plateau, elaborated for a royal family. Together with another Thracian masked helmet, however, more Eastern Mediterranean or "oriental" facial features are shown here, which differ significantly from the classicism prevailing in the Roman Empire at that time. In particular, two even older masks or mask helmets from Haltern and Kalkriese , which, in contrast to the ones mentioned, actually come from Roman production, would clearly show their correspondence to the Augustan ideal of beauty, which raises doubts about the oriental thesis.

- Hellenistic thesis . Ortwin Gamber, an Austrian art historian and weapons expert, sees in the "oriental" masked helmets imitations of older Hellenistic models. The weapon frieze of Pergamon as the oldest representation of a real masked helmet would prove this. The Roman mask helmet tradition would also have its origin in Hellenism.

- Thracian thesis . This theory was first applied by Friedrich Drexel (1885–1930) and later spread by the Bulgarian researcher Iwan Wenedikow (1916–1997). The thesis sees the origin in Bulgaria and introduces one from the 4th century BC. A helmet of the Phrygian type that was found there. However, the proponents of this thesis have not yet been able to provide any link between this Phrygian type and the helmets of the early Roman Empire. The discovery of a striking number of Roman masked helmets in Thracian and Gallic tombs was also cited as evidence for this theory. Thracians in Roman service would then have brought the helmet to Gaul. Just as well - according to Maria Kohlert - the increased number of helmet finds in the two regions can be explained by local customs.

- Italian thesis . The archaeologist Harald von Petrikovits (1911-2010) and Maria Kohlert-Németh have spoken out in favor of a purely Italian origin for the Roman masked helmets. Both saw a connection with the ancient Roman custom of ancestral masks and the equestrian games, which were often performed at funerals in early Roman times. Emperor Augustus in particular , who revived many old traditions, could have brought the equestrian games back to life; this revival would coincide with the first appearance of Roman military masked helmets. However, this thesis apparently excludes the existence of the military masked helmet, which was fully developed in the Hellenistic period, as it is depicted on the weapon frieze in Pergamon. Overall, it can be said that a Hellenistic origin would not rule out Italian influences.

The Roman mask helmet

Science knows three sources for research into Roman mask helmets, which in the best case complement one another. Archaeological finds are initially the most important component for research; stone images, mostly of tombs, can, among other things, in some cases provide information about the former bearers. The last, sparse source is the few written records. Some ancient books on the Roman military are known only by name. On the other hand, the art of Arrian tactics (created in 136/137 AD), which has been preserved , mentions some important, otherwise unknown details, such as the fact that masked helmets were decorated with gold drooping helmet bushes. The use of masked helmets by the Roman cavalry is certain, but the interpretation of some researchers that they have also identified masked helmets on gravestones of field sign bearers ( signiferi ) is controversial . Any major use by the infantry is generally denied. Masked helmets were not only used in the exhibition battles of the Roman cavalry, but also on other ceremonial or triumphant occasions. It is also discussed in research whether and to what extent this type of helmet was also worn during combat.

The Roman masked helmets divided the research into different main and sub-groups. The centuries of use of this type of military helmet have inevitably been subject to various fashions. With the advent of the helmet masks, the oldest piece to date from an ancient battlefield near Kalkriese and dated to the year 9 AD, the classicism promoted by Emperor Augustus dominated the formal language of Roman equipment. Mask helmets with a Hellenistic-Roman character were also made in the 2nd century, but masks with an “oriental” influence are now also clearly emerging. They all, or at least the majority, represent the faces of women. The influence of the Orient became firmly established in urban Roman fashions and customs in the 3rd century and ultimately led to a state-mandated, absolutist imperial cult. The formal tradition of Roman mask helmets, on the other hand, breaks off just as suddenly as it was founded.

Classification of Roman mask helmets

Some Roman mask helmet types are in themselves their own designs, others combine standard models of cavalry and infantry with masks. Therefore, for example, the Koblenz-Bubenheim / Weiler type can also be found in maskless headgear. Most types also have a wide variety of subspecies.

| Name (type) | earliest time | comment |

|---|---|---|

| Kalkriese | 9th AD | The only specimen found so far was discovered in 1990 during excavations on the Kalkriese battlefield. |

| Nijmegen-Kops plateau | 1st quarter of 1st century AD | The oldest find to date comes from a royal tomb in Homs, Syria. |

| Koblenz-Bubenheim / Weiler | 1st quarter of 1st century AD | |

| Weisenau -Kalkriese (mixed type) | around 50 AD | The only specimen found so far is said to come from a grave in Bulgaria. Instead of a long neck shield, this Weisenau was designed with a very short, straight cavalry neck. |

| "Male Female" | 2nd half 1st century AD | |

| "Female" (Hellenistic-Roman) | 2nd half 1st century AD | The oldest find so far comes from Rapolano , Tuscany, Italy. |

| Ribchester | late 1st century AD | The oldest find so far comes from Ribchester, Great Britain and was discovered as early as 1796. |

| Newstead | late 1st century AD | |

| Alexander | 1st half 2nd century AD | The oldest find so far comes from a cave on Mount Hebron, Israel . Together with other Roman militaria, he probably came there during the Bar Kochba uprising (132-135 AD). |

| Pfrondorf | late 2nd century AD | Three-piece helmet with a fully removable visor in the center of the face covering the wearer's eyes, nose and mouth. Thomas Fischer believes that this helmet was also used in combat after the visor was removed. |

| Heddernheim | late 2nd / early 3rd century AD | |

| Phrygian | 2nd / 3rd Century AD | The only specimen, an occiput, was found north of Fort Vechten, Netherlands, in 1977. |

| "Oriental" (female, possibly also male) | 3rd century AD | Among other things, the masked helmets of the Straubing type have become known here |

Late antiquity

So far, research has only found scant traces of masked helmets from late antiquity. Remains of a few narrow iron masks with only hinted facial features were found in the Great Palace of Constantinople . Their timing is unclear. However, they are not in the tradition of older Roman masked helmets. Another late antique depiction was found on the reliefs of the Arcadius Column, erected in Constantinople around 400 AD. The original stone reliefs are lost today and are only known through redrawings from the 18th century. Furthermore, several ancient authors report the use of mask helmets by the heavy late Roman cavalry ( cataphracts ).

Early and High Middle Ages

In the Anglo-Saxon ship grave of Sutton Hoo from the first half of the 7th century a possibly older ornate helmet could be recovered, which is related to late Roman crested helmets , which appear in the finds at the end of the 3rd century at the earliest. The helmet from Sutton Hoo is usually assigned to the Nordic crested helmets, which are also known as glasses helmets or Vendel helmets. Like the late antique masks, the one from Sutton Hoo is very narrow and represents the stylized face of a mustached man.

Equestrian peoples of the Eastern European steppes are also known to wear iron, mustached helmet masks. There they were partly in use until the high Middle Ages. Research suggests that these masks were intended for combat use. A derivation of these medieval masks from the Roman tradition is being discussed in science.

Western European pot and visor helmets from the Middle Ages are not actually masked helmets, even if some are equipped with accentuating eye, mouth or nostrils, among other things. Like the Roman gladiator helmets, they belong to their own class of helmets. Only the larval visors of the 16th century are an exception in their exaggerated and distorted grotesque. As a mummery , they offered amusement to the people and attention to the knight at tournaments.

Non-European cultures

The partial masks of the samurai helmets, which are often grotesquely designed, are not counted among the actual mask helmets, as they, like some European and non-European representatives, do not completely cover the face.

India

In the 18th century, heavily armored Sin warriors sometimes wore simplified face masks.

literature

- Hubertus von Gall : The equestrian combat image in the Iranian and Iranian-influenced art, Parthian and Sasanian times (= Tehran research. Vol. 6). Mann, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-7861-1511-7 .

- Ortwin Gamber: cataphracts, clibanaries, Norman riders. In: Yearbook of the Art History Collections in Vienna. Vol. 64, 1968, ISSN 0075-2312 , pp. 7-44.

- Jochen Garbsch : Roman parade armor (= Munich contributions to prehistory and early history. Vol. 30). With contributions by Hans-Jörg Kellner , Franz Kiechle and Maria Kohlert. Beck, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-406-07259-3 (exhibition catalog, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, December 15, 1978 - February 4, 1979; Munich, Museum of Pre- and Early History, February 16, 1979 - April 16, 1979 ).

- Norbert Hanel , Susanne Wilbers-Rost , Frank Willer: The Kalkriese helmet mask. In: Bonner Jahrbücher . Vol. 204, 2004, pp. 71-91, doi : 10.11588 / bjb.2004.0.33261 .

- Norbert Hanel, Uwe Peltz, Frank Willer: Investigations into Roman equestrian helmet masks from Germania inferior. In: Bonner Jahrbücher. Vol. 200, 2000, pp. 243-274, doi : 10.11588 / bjb.2000.0.62197 .

-

Marcus Junkelmann : The riders of Rome. von Zabern, Mainz;

- Volume 1: travel, hunting, triumph and circus races (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 45). 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1006-4 ;

- Volume 2: The Military Use. = Riding style and military use (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 49). 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1139-7 .

- Marcus Junkelmann: Horsemen like statues made of ore (= Antike Welt 27, special edition 1 = Zabern's illustrated books on archeology . ). von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1821-9 .

- Marcus Junkelmann: Roman cavalry - equites alae. The combat equipment of the Roman cavalry in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD (= documents of the Limes Museum Aalen. 42, ZDB -ID 1119605-1 ). Württembergisches Landesmuseum, Stuttgart 1989.

- Martin Kemkes , Jörg Scheuerbrandt (ed.): Questions about the Roman cavalry. Colloquium on the exhibition "Riders like statues made of ore. The Roman cavalry on the Limes between patrol and parade" in the Limes Museum Aalen on 25/26. February 1998. Württembergisches Landesmuseum, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-929055-50-3 .

- Maria Kohlert: Comments on a Roman face mask from Varna. In: Klio . Vol. 62, 1980, pp. 127-138, doi : 10.1524 / klio.1980.62.62.127 .

- Maria Kohlert: Comments on the typology and chronology of Roman face masks. In: Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Vol. 29, No. 1/4, 1981, ISSN 0044-5975 , pp. 393-401, ( digitized version ).

- Maria Kohlert: Mask as a portrait? Functional and aesthetic features of the Roman face masks. In: Scientific journal of the Humboldt University in Berlin. Social and Linguistic Series. Vol. 31, 1982, ISSN 0522-9855 , pp. 229-232.

- Leopold Schmidt (Ed.): Masks in Central Europe. Folklore contributions to European mask research (= special publications of the Association for Folklore in Vienna. Vol. 1, ZDB -ID 550056-4 ). Association for Folklore ao, Vienna ao 1955.

Web links

- Roman mask helmets , with pictures (English)

- Face mask for equestrian fighting games - 3D model in the culture portal bavarikon

Remarks

- ↑ Richard Delbrück : The Consular Diptychs and Related Monuments (= Studies on Late Antique Art History. Vol. 2, ZDB -ID 530605-x ). Text tape. de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 1929, p. 38.

- ↑ a b Hubertus von Gall: On the figural architectural sculpture of the Great Temple of Hatra. In: Baghdad communications. Vol. 5, 1970, ISSN 0418-9698 , pp. 7-32.

- ↑ Junkelmann: Riders like statues from ore. 1996, pp. 24-25.

- ^ Gamber: Kataphrakten, Clibanarians, Normannenreiter. 1968, p. 12ff.

- ^ Ortwin Gamber: Weapons and Armaments of Eurasia. A handbook on the history of weapons. Volume 1: Early times and antiquity (= library for lovers of art and antiques. Volume 51). Klinkhardt & Biermann, Braunschweig 1978, ISBN 3-7814-0185-5 , pp. 298f., 371.

- ^ Friedrich Drexel: Roman parade armor. In: Michovil Abramić, Viktor Hoffiller (eds.): Bulićev Zbornik. Naučni prilozi posvećeni Franu Buliću prigodom LXXV. godišnjice njegova života od učenika i prijatelja IV. octobra MCMXXI. = Strena Buliciana. Tiskara Narodnih novina et al., Zagreb et al. 1924, pp. 55ff.

- ↑ Maria Kohlert: Comments on a Roman face mask from Varna. 1980, p. 137ff.

- ↑ Harald von Petrikovits : Troiaritt and Geranostanz. In: Contributions to older European cultural history. Festschrift for Rudolf Egger . Volume 1. Verlag des Geschichtsverein für Kärnten, Klagenfurt 1952, pp. 126–143, here p. 138.

- ↑ Maria Kohlert: On the development, function and genesis of Roman face masks in Thrace and Lower Mossia. In: Scientific journal of the Humboldt University of Berlin, social and linguistic empires. Vol. 25, 1976, pp. 509-516.

- ↑ Junkelmann: Riders like statues from ore. 1996, p. 26.

- ↑ Junkelmann: Riders like statues from ore. 1996, p. 29.

- ↑ Arrian, Art of Tactics 34: 2-4.

- ↑ Junkelmann: Riders like statues from ore. 1996, p. 54.

- ^ Garbsch: Roman parade armor. 1978, p. 6.

- ↑ The Ribchester Helmet , British Museum (English)

- ↑ Junkelmann: Riders like statues from ore. 1996, p. 32.

- ^ Thomas Fischer : The Romans in Germany. Theiss, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1325-9 , p. 43.

- ↑ Junkelmann: Riders like statues from ore. 1996, p. 95.

- ^ David Nicolle : Romano-Byzantine Armies, 4th - 9th Centuries (= Men-At-Arms Series 247). Color Plates by Angus McBride. Osprey, London 1992, ISBN 1-85532-224-2 , p. 12.

- ^ Heiko Steuer : Helmet and ring sword. Splendid armament and insignia of rank Germanic warriors. In: Studies on Saxony Research. Vol. 6, 1987, ISSN 0933-4734 = publications of the prehistoric collections of the State Museum in Hanover. Vol. 34, pp. 190-236, PDF, 7 MB .

- ↑ Junkelmann: Riders like statues from ore. 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Gamber: Kataphrakten, Clibanarians, Normannenreiter. 1968, p. 7ff.