Hatra

Coordinates: 35 ° 34 ′ 33 ″ N , 42 ° 43 ′ 42 ″ E

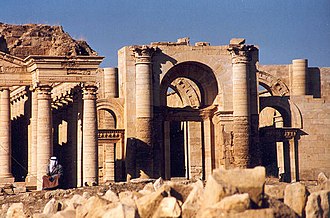

Hatra ( Arabic الحضر al-Ḥaḍr ; Aramaic ḥṭrʾ) was the capital of a Mesopotamian minor principality in the sphere of influence of the Parthian Empire . Because of its abundance of monuments, Hatra was one of the most significant sites of the Parthian era. It belongs to the world heritage of UNESCO . The ruins of the city are in what is now Iraq . In 2015 Hatra, like Palmyra, was largely destroyed by Islamists.

history

Hatrene

Hatra is located about 110 kilometers southwest of Mosul and 4 kilometers west of the Wadi al-Tharthar, a river ( wadi ) that rises in the Jabal Sinjar and has only temporary water . At that time the area around the city was called Hatrene. In the Parthian period (until AD 224) it represented a clientele kingdom of the Parthians , which belonged to the Parthian sphere of influence, but was ruled by its own king . In this way, the Arsacids who ruled Parthia were able to control a significant part of the Arab tribes in the region.

Development and history of the city

On the edge of the steppe in the wider border area between the great powers of that time, the Parthian Empire of the Arsacids and the Roman Empire , an urban center supported by nomadic tribes developed in the 1st century AD. The name Hatra (Aramaic ḥṭrʾ) means something like “walling” or “settlement”. The city was closely linked to the Arsacid Empire. In the course of the 2nd century it was expanded into a walled, over 300 hectare complex, in the basic shape approximating a circle with a central Temenos area (temple district). The importance and strength of Hatra become clear in the multiple, unsuccessful attempts by Roman emperors (including Trajan 117 and Septimius Severus 197 and 199) to conquer the city. In the sixties of the 2nd century the ruler Hatras assumed the title of King of the Arabs . Its importance is controversial in research. Most likely the title was bestowed by the arsakid Parthian king, to whose kingdom Hatra belonged.

In 224, the Sassanids overthrew the Arsakid dynasty in Iran. Like Armenia, Hatra remained loyal to the old dynasty and was now apparently seeking the support of the Imperium Romanum : three inscriptions by Roman soldiers from the years 235 and 238 attest to the at least temporary presence of imperial troops in the city. But in the end the Romans, whose empire had been increasingly bound by other problems since 235 (see also Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century ), could not prevent the fall of Hatras. After at least two years of extremely complex siege, either the Sassanid king Ardashir I or his son Shapur I took the city in 240 or 241. According to a later legend, the Sassanids owed their victory to the betrayal of the daughter of the King of Hatra, who is said to have fallen in love with Shapur I and opened a way for him to the city. As the latest studies on the extensive siege complexes, including the second round wall around Hatra, show, the case of Hatras was probably simply the result of the very systematic siege by the Sassanids, coupled with the ineptitude of the Romans and the city's nomadic allies to successfully shock them. The conquest of Hatra was important for the Sassanids to bring the rich Mesopotamia firmly under their control; At the same time, it formed a strategic prerequisite for the subsequent attacks on Roman territory, which would severely affect the Roman Empire in the years up to 260. Hatra itself seems to have been abandoned after the Sassanid conquest.

The rulers of Hatra

|

mrj´ (Marja, "Lord") |

mlk´ (king)

|

research

The first modern explorer to survey the area of the city in 1836 and 1837 was the British doctor, then at the British Consulate General in Baghdad, John Ross . Hatra was systematically researched for the first time by the archaeologists of the German Orient Society, who worked under the direction of Walter Andrae in Assur , 50 km away . Between 1906 and 1911 they made an overall map of the city and its state of preservation on their day trips. Aerial photographs of the site were taken in the 1930s. In 1951 the Iraqi antiquity administration began again with excavations. Since then, large parts of the city have been exposed, including smaller sanctuaries such as Temple XIV . The excavation teams were fortunate that after the destruction in 240/41 there were never large numbers of people living nearby, who, as has often happened with other ruins, used the remains of the city as a source of building material. In 1985 Hatra was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

In a sub-project of the Collaborative Research Center “Difference and Integration”, the reasons for the development of the city are discussed against the background of the economic and political interaction between nomads , settled people and the state . Then the question of the relations between the city, the king of the Arabs and the great powers, in particular the Arsacid Empire, takes center stage. The function of Hatras is described as "dimorphic", as a link between nomads and the state. Only in 2006 were huge fortifications discovered east of the city with the help of aerial archeology, which could be identified as the fortified camp of the Sassanids during the siege of Hatra around 239/40.

Destruction by the "Islamic State"

When Islamists destroyed numerous art objects in the Museum of Mosul in February 2015 , many unique objects from Hatra fell victim to this iconoclasm .

The archaeological site itself has also been under the control of the so-called Islamic State (IS) since summer 2014 . At the beginning of March 2015, the Iraqi Ministry of Culture reported that IS activists and fighters had started to systematically destroy Hatra with bulldozers and explosives after Nimrud . The ruins are said to have been looted beforehand. In the ideology of the IS, the temples, statues and images are considered idolatry , which in their opinion is incompatible with Islam.

Hatra was then included in the UNESCO Red List of World Heritage in Danger. In the spring of 2017, the Islamists withdrew from the city after fierce fighting.

Film set

The temple ruins of Hatra served as the set for the 1973 horror film The Exorcist . The actor Max von Sydow can be seen in the opening sequence .

See also

literature

- Klaus Beyer: The Aramaic inscriptions from Assur, Hatra and the rest of Eastern Mesopotamia. (Dated 44 BC to 238 AD). Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1998, ISBN 3-525-53645-3 .

- Lucinda Dirven (Ed.): Hatra. Politics, Culture and Religion between Parthia and Rome (= Oriens et Occidens . 21). Steiner, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-515-10412-8 .

- Peter M. Edwell: Between Rome and Persia. The middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra under Roman control. Routledge, London et al. 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-42478-3 .

- Stefan R. Hauser : Hatra and the Kingdom of the Arabs. In: Josef Wiesehöfer (ed.): The Parthian Empire and its testimonies. Contributions from the international colloquium, Eutin (June 27-30, 1996). = The Arsacid Empire. Sources and Documentation (= Historia . Individual writings. 122). Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07331-0 , pp. 493-528.

- Michael Sommer : Hatra. History and culture of a caravan town in the Roman-Parthian Mesopotamia . Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-3252-1 .

- David J. Tucker, Stefan R. Hauser: Beyond the World Heritage Site. A huge enclosure revealed at Hatra. In: Iraq. Vol. 68, 2006, pp. 183-190, JSTOR 4200615 .

- Francesco Vattioni: Le iscrizioni di Ḥatra (= Istituto Orientale di Napoli. Annali. Supplemento. 28, ZDB -ID 194525-7 ). Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli, Naples 1981.

- Francesco Vattioni: Hatra (= Istituto Orientale di Napoli. Annali. Supplemento. 81). Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli, Naples 1994.

Web links

- Hatra . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica (English, including references)

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

Remarks

- ↑ See Hauser: Hatra and the Kingdom of the Arabs. In: Josef Wiesehöfer (ed.): The Parthian Empire and its testimonies. Stuttgart 1998, pp. 493-528.

- ↑ Cf. Vattioni: Le iscrizioni di Ḥatra. 1981, pp. 109-110.

- ↑ See Tucker, Hauser: Beyond the World Heritage Site. In: Iraq. Vol. 68, 2006, pp. 183-190.

- ^ John Ross : Notes on Two Journeys from Baghdád to the Ruins of Al Hadhr, in Mesopotamia, in 1836 and 1837. In: Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. Vol. 9, 1839, pp. 443-470, JSTOR 1797735 .

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Center: Hatra. Retrieved September 23, 2017 (English).

- ↑ World cultural heritage blown up: Jihadists also destroy the ancient city of Hatra. In: Spiegel Online . March 7, 2015, accessed March 7, 2015 .

- ^ The Iraqi site of Hatra added to the List of World Heritage in Danger. July 1, 2015, accessed October 19, 2016 .

- ↑ Bild.de: Location for cult horror film: ISIS conquers "Exorcist" temple