Aššur (city)

Coordinates: 35 ° 27 '23 " N , 43 ° 15' 37" E

Aššur or Ashshur ( Akkadian ; Arabic / Persian اشور), also written Assur (today Kalat Scherkât / Qal'at Šerqat ), is a historic city in the north of today's Iraq . Aššur is located on the right bank of the Tigris , north of the mouth of the small Zab . The city gave its name to the Assyrian culture .

history

3rd millennium BC Chr.

The archaeological evidence suggests that the city was founded before the 25th century BC, possibly as early as 2700 BC. In ancient Sumerian times. The oldest traces of a settlement of Assur can already be found in layer H of the Ištar temple ( archaic Ištar temple ), which represents the oldest archaeological evidence of the city, and in the oldest layers under the Old Palace and other temples of the main gods. In the following Akkad period (approx. 2340–2200 BC) (layer G / F of the Ištar temple) Assur was under the rule of the kings of the Akkadian Empire. At the time of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur (approx. 2100–2000 BC), the name of Zariqum as governor of Assur is passed down under Amar-Sin through an inscription that was found in the Ishtar temple. He later became governor of Susa . The inscription on a limestone slab is a dedication to d Belat-ekallim (Nin-é-gal, mistress of the palace) for the life of Amar-Sin, king of Ur.

2nd millennium BC Chr.

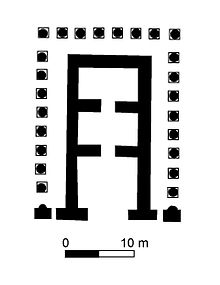

After the end of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur, independent local princes took over the rule of the city, which quickly developed and became a center of long-distance trade, which maintained a network of trading establishments in Anatolia ( Karum period ). In Ashur in this time of created Ashur - and the Adad Temple ; the Ištar temple was renewed (layer D). In addition, the city received its first fortifications during this time.

Towards the end of the 19th century BC Aššur became under the rule of Šamši-Adads I (1808–1776 BC) the political, administrative and religious center of an Assyrian territorial state that was emerging . At that time the Old Palace, the Ashur-Enlil- emerged in Assyrian ziggurat and a new Ashur temple Ehursakurkurra whose layout was maintained until the end of the Assyrian Empire. After the death of Šamši-Adad, the empire he had created fell apart, and Aššur lost its importance again.

In the 16th century BC The fortifications of the city were expanded further. One of the responsible rulers, Puzur-Aššur III. (Middle of the 2nd millennium BC), the southern residential area (the new town) connected to the old town center. Around this time, a double temple for the moon god Sin and the sun god Šamaš was built. A little later, Aššur became part of the Mitanni empire, which stretched over large parts of northern Mesopotamia and Syria .

Under the Central Assyrian kings Eriba-Adad I (1382-1356 BC) and his son Aššur-uballiṭ I (1355-1320 BC), Assyria freed itself from Mitannic supremacy and in the 13th century BC. BC once again represented one of the strongest political forces in the Middle East . The rulers Adad-nirari I (1295–1265 BC), Shalmaneser I (1264–1234 BC) and Tukulti-Ninurta I (1233 –1197 BC), Assur owed an extensive building program that included both the reconstruction and restoration of its temples, fortifications and the old palace. In addition, Tukulti-Ninurta I had a new palace built in the northwestern part of the city. End of the 12th century BC At the time of Aššur-reš-iši I (1133–1116 BC) and Tiglat-pileser I (1115–1075 BC) the Anu-Adad temple was built .

1st millennium BC Chr.

Under King Aššur-nâṣir-apli II. (883–859 BC) the political center of Assyria was moved to Nimrud . Under Sargon II. (721–705 BC) the newly founded city of Dur Sharrukin became the residential city. Sargon's son Sennacherib (705–682 BC) made the city of Nineveh the new center of power in Assyria. As the residence of the national god Assur , the city remained the religious center of the Neo-Assyrian Empire despite the relocation of the seat of government, which was also underpinned by numerous building activities by the Neo-Assyrian kings, such as the establishment of the festival house ( éakitu ) by Sennacherib. The city covered about 90 hectares. The rulers of Assyria were buried here until the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and several sarcophagi of Assyrian kings were discovered under the Old Palace . Between the two walls of the city was a row of steles with the images of the kings and the eponymous officials Aššur, queens, like Libbāli-šarrat also erected steles here. In 614 BC The city was conquered and destroyed by the army of the Median king Kyaxares II .

The shift in the political focus of the empire is certainly the reason that the city plays almost no role in the Bible, unlike Nineveh. It hardly appears in the texts of the classical ancient world either, although unlike Nineveh , for example , it was by no means perished after the conquest .

Resettlement and use after the turn of the century

In the 1st century BC Aššur was repopulated and the city now became a Parthian administrative center. During this time an agora with public buildings was built in the north of the city . A new palace was built in the south. A new sanctuary for the god Assor was built on the site of the old Assyrian temple of Ashur. The upswing was short-lived, however, under the Sassanid ruler Shapur I (241–272 AD) the city was destroyed again.

However, the place was also inhabited again in the Islamic period, but only between the 12th and 13th centuries AD is there evidence of a larger settlement again. It belonged to the state of the Zengids of Mosul . Later, the city belonged to Ilkhan -Reich. After that the city fell into disrepair, at most Bedouins still pitch their tents in the ruins . Part of the urban area was used as a cemetery until the 1970s.

Since 2003 Ashur World Heritage of UNESCO . With the construction of the Makhul Dam , the ancient site was threatened by flooding. However, the dam project has not been resumed since the 2003 Iraq war. As the future and the integrity of the city are not guaranteed, Assur remains on the Red List of World Heritage in Danger .

Archaeological site

Excavation history

Since 1898 the German Orient Society (DOG) planned excavations in Assur; it was to be the first excavation company of the newly founded company.

Robert Koldewey and Eduard Sachau had already undertaken a research trip to Mesopotamia in 1897/98 to look for a suitable excavation site. It was hoped that numerous royal inscriptions could be found in the first capital of the Assyrian Empire. Also Warka and Senkere were considered. Finally, on the advice of Koldewey, it was decided to first excavate in Babylon (Kasr). It was not until 1900 that the Assyriologist Friedrich Delitzsch campaigned again for excavations in Aššur and was able to win the emperor's support. It was also feared that the British might precede the Germans at this historically important place. After all, as Matthes wrote, Assyria and Babylon had become “objects in the […] cultural competition of nations”.

On March 21, 1901, Delitzsch was received by Abdülhamid II , but was initially unable to obtain excavation permission because there was a Turkish barracks on the site. Permission was finally given on July 20 by a telegram from Abdülhamid to Wilhelm II , who funded the excavations with 50,000 marks from his private box. The research would not have been possible without his support, mainly because the excavation site was on the Sultan's “crown property” and barracks had been built on the hill where the “Adad-nirari's I” palace stood. Walter Andrae , who had previously been Koldewey's assistant in Babylon, was entrusted with the excavation . Andrae arrived in Aššur in August 1903, but had to overcome numerous difficulties with the local authorities until he was finally able to start the first prospecting work in mid-September. The establishment of a German consulate in Mosul in 1905 brought some relief. During the excavations from 1903 to 1914, the Tiglat-pileser I library was brought to light .

There were disputes regarding the division of the finds. As the company's financier, the DOG claimed the findings entirely for themselves or for Germany, and German newspapers even claimed that the Sultan had given the emperor the hill and all of the finds. In contrast, the director of the museum in Constantinople , Hamdi Bey , claimed all the finds. Since 1899, however, an agreement between the Ottoman government and the Berlin museums had existed through an exchange of notes, which guaranteed them the selection of half of the finds. On this basis, the division of the Aššur finds was carried out in 1907 and 1914.

The northern part of the city on the old arm of the Tigris with the temple and palace districts has been excavated. In addition, a search trench was dug in a west-east direction, which, among other things, brought a large number of medical texts to light in the house of the conjuring priest. The southern part of the city and the new town have not yet been excavated. To research the residential area, Andrae had five meter wide search trenches dug 100 meters apart. This technique was already used in 1902/1903 during the excavation of the nearby Tell Farah and had the aim of finding possibly larger buildings. The excavated soil was neither driven nor later backfilled into the trenches, as only a limited search excavation was planned from the start. The workers trained during the excavations in Aššur, many of whom came from the nearby town of Shirqat , could also be employed as qualified skilled workers in later excavations. Their descendants are valued workers under the name of "Schirqati" during excavations to this day.

In 1979 the Iraqi Antiquities Administration continued exploring the city; this lasted (with interruptions) until 2002. New German excavations took place in 1988–89 ( Reinhard Dittmann , Free University Berlin), 1989–1990 ( Barthel Hrouda , University of Munich) and 2000–01 ( Peter A. Miglus , University of Halle ). Since 1997, the German Research Foundation has funded the Aššur project, which was launched by the German Orient Society and the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin to scientifically process the German excavation from 1903–1914.

Destruction by the Islamic State

On May 28, 2015 Iraqi sources reported that the Islamic State (IS) blew up parts of the citadel. IS had previously destroyed the Assyrian ruined cities of Nimrud and Nineveh.

literature

- Walter Andrae : The resurrected Assyria. 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-406-02947-7 .

- Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum : The Assyrians. History, society, culture. 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-50828-8 .

- Stefan Heidemann: Al-'Aqr, the Islamic Assyria. A contribution to the historical topography of northern Mesopotamia. In: Volker Haas, Hartmut Kühne u. a. (Ed.): Berlin contributions to the Middle East. Volume 17. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1996, pp. 259-285 ( PDF; 3.2 MB ).

- Susan L. Marchand: Down from Olympus. Archeology and Philhellenism in Germany 1750-1970. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1996, ISBN 0-691-04393-0 (English).

- Joachim Marzahn , Beate Salje (ed.): Resurrecting Assur. 100 years of German excavations in Assyria. (= Companion volume to the exhibition of the same name). von Zabern, Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-3250-5 .

- Olaf Matthes: On the prehistory of the excavations in Assur 1898–1903 / 05. In: Communications from the German Orient Society in Berlin . Issue 129. Berlin 1997, ISSN 0342-118X , pp. 9-27.

- Peter A. Miglus : The residential area of Assur, stratigraphy and architecture. (= Scientific publication of the German Orient Society. Volume 93). Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-7861-1731-4 .

- Conrad Preusser: The palaces in Assur. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-7861-2004-8 .

Web links

- Assyria . In: Ancient.eu, January 27, 2017 (English)

- Assur in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (English)

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Assur at Google Arts & Culture

- Assyria . In: Orient-Gesellschaft.de

- Assur project of the Institute for Prehistory and Early History and Near Eastern Archeology at Heidelberg University

- Assur - center of the cosmos . In: BibelAbenteurer.de

- Literature by and about Aššur in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ according to the middle chronology

- ^ Peter A. Miglus, 1996

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Center: Ashur (Qal'at Sherqat). Retrieved September 23, 2017 (English).

- ↑ UNESCO Red List

- ^ Association news , in: Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 15 (1902) 1–6, here: p. 2.

- ^ Eva Strommenger , Wolfram Nagel, Christian Eder : From Gudea to Hammurapi. Fundamentals of art and history in ancient Near East Asia. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2005, p. 218

- ↑ http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/isis-blows-unesco-world-heritage-assyrian-site-ashur-near-tikrit-1503367