Jebel Sinjar

| Jebel Sinjar | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Jebel Sinjar from orbit |

||

| Highest peak | Çêl Mêra ( 1463 m ) | |

| location | Ninawa Province , Iraq | |

|

|

||

| Coordinates | 36 ° 22 ′ N , 41 ° 42 ′ E | |

The Jebel Sinjar ( Arabic جبل سنجار Jabal Sinjār , DMG Ǧabal Sinǧār ; Kurdish چیای شهنگال / شهنگار Çiyayê Şingal / Şingar ) is a mountain range in northern Iraq west of the city of Mosul near the Syrian border, which was shaped by the Yazidi farming and shepherd culture that was finally destroyed in the second half of the 20th century .

geography

The elongated, largely karstified Jabal Sinjar rises abruptly at a relative height of around 500 to 1000 meters from a semi-arid , partly dry- land plain between the two rivers Tigris and Chabur and belongs to Jazira . It extends approximately 60 km from east to west. At its highest point, the Jabal Sinjar with the Çêl Mêra (also Chermera , German "forty men") reaches 1,463 meters. Its apex region has been eroded , so that today it consists of several layer ridges in which rocks from the Eocene and Cretaceous periods come to light. The highest peaks are formed by mighty limestone blocks . The city of Sinjar is located at the southern foot of the ridge . A road from Mosul to Ar-Raqqa in Syria, used since the 11th century, runs there .

geology

The Jebel Sinjar is located in the northeast of the North Arabian Plate and is the part of the Sinjar uplift area of the same name that is visible on the surface of the earth. The rock strata, raised by up to 1.5 km in the center of the uplift area, originate from a period from the Paleozoic to the Cenozoic . The crystalline basement is about six kilometers deep. The exact composition of the deeper layers of the overburden is not known, as Cambrian rocks have not yet been drilled. Mighty mudstones from the Ordovician have been found several times, as has the lower Silurian . Rocks from the Upper Silurian and Devonian Mountains are completely absent; only in the Carboniferous were clastic rocks deposited again in an elongated rift zone . No deposits have survived from the Upper Carboniferous or from the Lower Permian . This could be due to erosion of the affected layers in the early Triassic . Until the end of the Jura , shallow water sediments ( dolomites , limestones , marl and sandstones ) were deposited , of which the mighty dolomites of the Triassic have been passed down, while the younger layers were again largely eroded. During the Upper Jurassic and the Cretaceous, the sedimentation was dominated by rift formation, which led to the deposition of the mighty Shiranish Formation prior to a major northward displacement. Also in the early Tertiary to the Miocene there was deposits in the area of the later Jabal Sinjar, but the previously so active rift formation had come to a standstill. The deposits are mainly determined by limestone, gypsum and anhydrite , which in the Pliocene changed into clay and sandstones and conglomerates .

Following the Zagros - folding of the Pliocene the entire area subject to the northern Arab plate of a strong, directed approximately from north to south voltage. Above all, the mighty sediment sequence, which had deposited in the rift zone that was repeatedly active between the Carboniferous and Upper Cretaceous, was pushed to the north at the northern rift fault and the interior of the rift was lifted up. The highest arched rock layers were eroded, so that older layers emerged in the core of the arches between the Quaternary and younger Tertiary layers, which were widespread in the surrounding area . Similar to the Jabal Abd el-Aziz located further west in Syria, the Jebel Sinjar ridge is the superficial expression of a geologically very young anticline with a complicated history. The asymmetrical structure of this anticline is reflected in the current surface shape: deeply cut valleys furrow the moderately steep southern slope and almost flat ridges form its apex, while the northern slope drops off steeply (see photo opposite).

climate

At Jabal Sinjar there is a semi-arid subtropical climate of Mediterranean characteristics with hot, dry summers and cool, damp winters. Comparable climatic values are available for the city of Sinjar at the foot of the ridge. This is where the maximum temperature is with a daily average of 33.9 ° C in July and August, the maximum of precipitation with 84 mm in January. The annual average temperature is 20 ° C. The annual precipitation has a height of 449 mm. Depending on the altitude, the temperature values in Jabal Sinjar are on average lower and the precipitation values higher. This means that the ridge regions wear a permanent snow cap in winter.

vegetation

The zone above 800 meters is a potential forest area, but due to human influences such as logging and grazing , the oak forests to be expected there are almost only found in very light or inaccessible areas. They were largely replaced by steppe flora adapted to the altitude . Large areas of this zone are characterized by rock corridors. Because of the lower rainfall there is a warmth-loving steppe flora below 800 meters. In the deeply cut valleys, on mostly temporary watercourses, where it has not been replaced by arable terraces, species-rich canyon vegetation thrives, for which the wild fig ( Ficus carica ), cultivated by the Yazidis, appears typical.

From 1965 many Yazidi villages were destroyed and the residents were relocated. Since then, previously cultivated areas have been subject to secondary natural succession . They are weed and bushy. Wherever terraces collapse and the irrigation systems fall apart, a Mediterranean maquis can spread. Soil erosion continues. Oak and maple forests ( e.g. Acer monspessulanum subsp. Cinarescens ), on the other hand, can recover if they are no longer used for wood production and grazing.

Land use

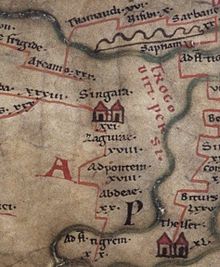

The land use of the Yazidis shaped Jabal Sinjar is mainly done through grazing. In addition to the open areas, which are largely overgrazed , forests are also used as sheep pastures . In addition, are usually located on the valleys and partially terraced and irrigated mainly arable land, grain , vegetables and tobacco grown. In the Islamic Middle Ages, mulberries were also cultivated here for a flourishing silk production . Fruit groves follow on the slopes. Historical reports praise the figs and dates of Jabal Sinjar. ( Map )

A large part of the livestock comes seasonally with migrant herdsmen from villages outside the Jabal, so it corresponds to the transhumance system. The inhabitants of the Jabal, on the other hand, tend to graze all year round, which is only interrupted if the cattle are driven to harvested wheat and barley fields in the summer . In winter they are fed. All shepherds have free access to pastureland, for which there are no special property rights and for which there are no public institutions that organize grazing. A comparison of satellite images from 1988 and 1995 shows a strong degradation of the natural plant cover, which is also due to overgrazing . This process continues. It is exacerbated by a decrease in rainfall in recent years.

With the destruction of Yazidi villages, the resettlement of their inhabitants in central villages outside the ridge as part of the Iraqi Arabization policy and the resulting rural exodus, the traditional Yazidi farming and pastoral culture has perished. The cultivation of arable and vegetable crops within the Jabal Sinjar is now largely self-sufficient . The Yazidi farmers who live in the central villages can only get to their sometimes distant usable areas in the interior of the ridge via arduous routes. They often only run agriculture and grazing as a sideline . They commute to distant cities where they can find work and only come back to the families who have remained in Jabal Sinjar or in the central villages at intervals of several months.

raw materials

The large limestone and gypsum deposits of the Jabal Sinjar are the basis for a cement factory founded in 1981 , which started operations in 1985 and has been out of operation from the beginning due to the wars in the region. It is located about 20 kilometers east of the city of Sinjar on highway 715 towards Mosul. The raw material comes from the eastern foothills of the ridge ( map ).

history

The rugged ridge, equipped with natural caves, was a well-known retreat for the people of the region throughout history. At the foot of the Jabal Sinjar is the ancient Singara , whose name is etymologically related to Sinjar. The ridge was a scene of the wars between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire . After the Roman conquest of the area, Singara served as a base for the Roman Legion I Parthica . The jabal itself belonged to the new Roman province of Mesopotamia , which only existed for a short time. Later the ridge was the scene of the fighting between Byzantium and the Sassanid Empire . Several bishops who were either Nestorian or Jacobite are attested for the region . Zoroastrians and Jews also lived here . The Islamic conquest of the area brought about a decline in Christian culture. The Jebel Sinjar became part of the Diyar Rabia Province and Arab tribes came to the region.

The area was conquered by the Hamdanids in 970 and later flourished under a side branch of the Zengids . The Ayyubids followed in the first half of the 13th century . Orally transmitted reports from Yazid tribes of the eastern Jabal Sinjar connect the penetration of Yazidis into the Jabal in the second half of the 13th century with Sharaf al-Din Muhammad. Ibn Battuta, on the other hand, reported in the 14th century about Kurdish tribes in northern Jabal Sinjar without explicitly mentioning the Yazidis. A little later, the Qara Qoyunlu ruled the region first, then the Aq Qoyunlu , who were defeated by the Safavids in 1507/1508 .

In 1534 the Ottomans wrested power from the Safavids. Among them, the area around the Jabal Sinjar was a sanjak of the Diyarbakir province . In the early Ottoman period, more Yazidis came to Jabal Sinjar in several waves of settlements, mainly from the Sheikhan area. In doing so, they gradually replaced and supplemented the existing Christian population, which was able to maintain their identity. In the 17th century, according to the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi , around 45,000 Yezidi and Sufi Kurds (“Bapiri”) lived on the Jabal Sinjar, who was also called Saçlı Dağı (“Mountain of the Hairy”) in allusion to the hairstyle of the Yazidis Arabs also lived in the city of Sinjar. Evliya described in detail how in 1640 Ottoman troops under the command of Mustafa Pasha Firari devastated 300 Yazidis villages and killed around 1,000 to 2,000 Yazidis who had sought refuge in caves.

Until 1830 the area was part of the Sanjaks Mardin . After that it belonged to Mosul. In the 1830s, the ambitious Kurdish prince Mohammed Pascha Rewanduz von Soran began a campaign against the Yazidis. Many people were killed and many Yazidis fled to Mosul. The British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard took part in an Ottoman expedition of Tajar Pasha to the Jabal Sinjar in October 1846, during which the area destroyed by a former governor of Mosul was to be examined. The enterprise ended with the destruction of a Yazidi village and the killing of many residents. Layard reported on this and on the living conditions of the Yazidis in Jabal Sinjar. He was the first European who wrote extensively about the Yazidis , whose "Feast of the Assembly" (Cejna Cemaʿîye) he could experience in Lalisch . Layard explained that the Yazidi inhabitants of the ridge not only always ran the risk of being persecuted, but were also a constant threat to those traveling through the region:

“Hence it was not unnatural that the yezidi should use every opportunity they had to take revenge on their oppressors. They formed gangs and for a long time were the terrors of the country. No confessor of Allah who fell into their hands was spared. Caravans were looted and merchants mercilessly murdered. But the Christians did not find them difficult; for the Yezidi saw them as fellow sufferers in the field of religion. "

The Yazidis did not bow to the Ottoman governor of Baghdad. So there was an uprising against the governor from 1850 to 1864. During the Ottoman rule, some Christian families took over the trade in agricultural products from the interior of the Jabal, mainly in the places at the foot of the Jabal, for example in Sinjar , Jaddala , Bardahali and Sakiniyya , and exported them to the big cities such as Mosul and Baghdad and further into the entire Ottoman Empire. Land reforms planned by the Ottoman governments in Jabal Sinjar were unsuccessful. They failed mainly because of the very independent Yazidi sheikhs and Mīrs and their families, who, as members of privileged castes, feared for their subsistence from tribal taxes.

From the 1880s onwards, the reading public in German-speaking countries learned a lot about the events on the Jabal Sinjar and the way of life of the Yazidis from Karl May's publications, which were summarized in the Orient cycle . May based it on the writings of Austen Henry Layard, where he also took over his errors.

At the end of the 19th century the persecution of the Yazidis of Jabal Sinjar by the Ottomans increased. In addition to converting to Islam, some Yazidis also used conversion to Christianity to escape it. When the Christians of the Ottoman Empire were persecuted in the course of the First World War in 1915/16, many Christian Armenians , Nestorians ( Assyrians and Catholic Uniate Chaldeans ) and Jacobites fled to the Jabal Sinjar. They were taken up by some Yazidi tribes and made up about 4 percent of the population of the ridge. At the same time, relations between Yazidis and Muslims deteriorated dramatically, and thus also between Yazidi tribes, where either Christians or Muslims lived.

After the First World War, the Jabal Sinjar was occupied by the British as part of the Vilayets Mosul and in 1924 it was added to the British Mandate of Mesopotamia . During this time, mainly Christian and Muslim traders from Mosul invested in the agriculture of the jabal, as was the case in the second half of the 19th century. They had branches in the city of Sinjar, financed herds of cattle, sheep and goats and concluded contracts with Yazidi farmers and shepherds or their heads for the delivery of agricultural goods such as figs, cotton, wool, dairy products and meat. In return, the villagers and cattle nomads increasingly bought goods that they could not obtain or manufacture themselves, such as sugar, coffee, clothing and spirits. With that, their subsistence economy changed towards a budding market economy. The flow of goods mostly ran via Mosul, even the export of goods to Syria took this route.

During the British mandate there were tendencies among the leaders of the Yazidis of the Jabal to break away from the religious dominance of the Sheikhan and the supremacy of a Mir family from Sheikhan and the administration in Mosul. They suggested, for example, that the Jabal Sinjar area be incorporated into French-administered Syria. The aim was to achieve decentralization and thus a strengthening of tribal responsibilities. The Iraqi administration was able to end this political turbulence with the backing of the British Royal Air Force , which is responsible for the security and administration of the Jebel Sinjar, and also rejected the claims that Kemalist Turkey made on the area. When the new state of Iraq was created, the Jebel Sinjar remained within its borders.

Since the independence of Iraq in 1932, the Jebel Sinjar has been part of the Ninawa Province . Since 1965, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, the Kurdish population from more than 160 villages in the Sinjar region has been deported due to the conflicts between the Iraqi government and the Kurds in northern Iraq and forced to live in twelve central, collective or model villages ( mujammaʿat) to live. Their original villages were either destroyed or left to members of Arab tribes. Since the Iraq war in 2003 there have been repeated attacks by Sunni extremists against the Yazidis in the region. The largest attack to date occurred in August 2007 and killed 336 people. Around 1,000 families were made homeless. The Jebel Sinjar was also the battlefield of the US armed forces stationed on its mountain ranges and in its vicinity.

For a number of years it has been discussed whether the Jabal Sinjar should be connected to the Autonomous Region of Kurdistan . In June 2014, Kurdish Peshmerga, with the help of the Kurdish-Syrian People's Defense Units of the PYD, took places around the Jabal Sinjar during military clashes with the troops of the Islamic State (IS). In August 2014, the US Navy supported the peshmerga in the rescue of 20,000-30,000 before the Yazidis IS with air strikes, in these skirmishes occurred for the first time the Yezidi vigilantes in appearance.

On October 20, the IS militias started a major offensive, able to advance quickly and encircle the pilgrimage site Sharaf ad-Din . According to eyewitnesses, the IS militia had advanced with 40 Humvees . Parts of the Yazidi vigilante groups under the command of Qasim Şeşo had withdrawn there. 7,000 civilians and a few hundred fighters are said to have fled into the mountains. The IS militias were able to encircle the defenders in the Sindschal Mountains again . On October 24th, the IS militia succeeded in ascending the south side of the mountains and shooting at the holy site of Memê Reshan. The defenders in the pocket consisted of units from the YPG , HPG , HPŞ and YBŞ . The trapped civilians and fighters were sporadically supplied by air.

particularities

- In 1980, a new mineral was discovered in the rubble of a wadi cut into the Jebel Sinjar , which was named Sinjarite . It is a calcium chloride precipitated from the groundwater with the chemical formula CaCl 2 · 2 H 2 O. Sinjarit is not very stable because it dissolves easily in water .

- Saker falcons , which are endangered in their population , were caught in the Jabal Sinjar and exported or smuggled into the Gulf States as "Sinjari" falcons .

- The now extinct Syrian half-ass (also called Syrian onager , Equus hemionus hemippus ) was the smallest subspecies of the Asiatic half- ass, attested as early as 7500 BC by bone finds for the region of Jabal Sinjar . One specimen was caught in the Iraqi-Syrian border area, in the foothills of the Jabal Sinjar, in 1911 and lived in Vienna's Schönbrunn Zoo until 1929 .

- In the Jabal Sinjar, various types of ammonites can be found in the formations of the upper campanium .

- It can only be assumed that people from the earliest settlements, not far east of the Jabal Sinjar, visited or used it. Tell Maghzaliyah, for example, is a fortified settlement from the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic B of the 8th – 7th centuries . Millennium BC This settlement can be compared culturally and chronologically with the sites of Jarmo and Çayönü . Other sites in the vicinity are Qermez Dere , Tell Sotto and Yarim Tepe I to IV. The then largely forested Jabal Sinjar was able to hunt down wood and the fruits of the wild pistachio ( Pistacia atlantica or P. khinjuk ) for the people of that time Wild boar and wild goats offer.

- South of the Jebel Sinjar runs a passage area between the east and west of the ancient Orient. Christine Kepinski in Grai Reš , on road 715 from Sinjar to the east, has been excavating a place here since 2001 , the superficial layers of which date from the 4th millennium BC and which illustrates the transition from village to city.

- The Wadi Adschidsch , which rises on the southern slopes of the Jabal Sinjar , crosses the state border to Syria through its southwestern course. It seeps into the salt pan of ar-Rauda . Its water supplied settlements whose archaeological sites were discovered in 1981. For example, Central Assyrian ceramics were found there .

literature

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition , article Sinḏjār by CP Haase.

- Nelida Fuccaro: The other Kurds. IBTauris Publishers, London, New York December 1998, ISBN 978-1-86064-170-1 .

- Graham Brew: Tectonic Evolution Of Syria Interpreted From Integrated Geophysical And Geological Analysis. Retrieved December 11, 2009 ( Cornell University Dissertation ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Eugen Wirth : With the Yazidi in Jebel Sinjar. In: Yazidi. God's chosen people or the 'devil worshipers' from Jebel Sinjar, Iraq. Catalog for the special exhibition April 30 to September 27, 1998, Museum für Völkerkunde Wien 1998, pp. 74–76

- ↑ Photo: Plain with grain fields in front of the Jebel Sinjar ( memento from November 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on December 1, 2009

- ↑ Jabal Sinjar. In Westermann Lexicon of Geography. 2nd edition, Braunschweig 1973

- ↑ Brew 2001, Fig. 3.3: Stratigraphy (geology) | Stratigraphic profile

- ^ Brew 2001, Fig.3.4

- ↑ Block diagram of the Jebel Abd el-Aziz , from Graham Brew: Tectonic Evolution Of Syria Interpreted From Integrated Geophysical And Geological Analysis. PDF, 5.6 MB, accessed December 19, 2009

- ↑ Topography of Jebel Sinjar and Jebel Abd el-Aziz. from Graham Brew: Tectonic Evolution Of Syria Interpreted From Integrated Geophysical And Geological Analysis. PDF, 5.6 MB, accessed December 19, 2009

- ↑ Climate values for Sinjar at latitude: 36 ° 19′N, longitude: 41 ° 49′E, elevation: 1562.0 ft, distance: 1.48 mi

- ↑ John S. Guest: The Yezidis: a study in survival. Routledge, London 1987, ISBN 0-7103-0115-4 , p. 3

- ↑ Snow on Jebel Sinjar: Photo from January 10, 2004 , accessed on December 19, 2009

- ↑ FAO Forestry country profiles - Natural forest formations. Accessed November 29, 2009. Charles Keith Maisels: Early Civilizations of the Old World. London 1999, p. 124. More detailed historical information on individual species in the annals of the Natural History Museum in Vienna. XXVI. Volume, 1912, search term Sinjar Accessed November 29, 2009

- ↑ Christine Allison: The Yezidi oral tradition in Iraqi Kurdistan. Richmond, Surrey 2001, pp. 29f

- ^ Joseph Bornmüller: A contribution to the knowledge of the flora of Syria and Palestine. Zool. Bot. Ges. Austria, 1898, p. 571f , PDF, 7.33 MB

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition, article Sinḏjār by CP Haase

- ↑ See also a photo of Ackerterrassen accessed on December 1, 2009.

- ↑ Changes suffered by the Mediterranean rangelands in the recent past: ICARDA's experience PDF, 1.4 MB, accessed on November 23, 2009

- ^ IAU report: The humanitarian situation in Iraq. Therein: Iraq - Cropland affected by drought in 2008 - 2009. ( Memento from January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) PDF, 277 kB, accessed on December 6, 2009.

- ^ Eugen Wirth: Agrarian reform and rural emigration in Iraq. In: Erdkunde 36 (1982), pp. 192-196

- ↑ Irene Dulz: The Yezidi in Iraq - between "model village" and escape. Studies on the contemporary history of the Middle East and North Africa, Volume 8, Hamburg 2001, pp. 54–59

- ^ Eva Savelsberg, Siamend Hajo: Expert opinion on the situation of the Yezidis in Iraq. (PDF, 181 kB). Accessed February 12, 2018.

- ^ Iraqi cement focus. In: Global Cement , January 24, 2013 (English); Luke Coleman: Sinjar Cement Factory - The Cornerstone Of Redevelopment. In: Yalla Iraq , May 12, 2016.

- ↑ Konrad Mannert: Geography of the Greeks and Romans , Volume 5, Nuremberg 1797, p. 310

- ↑ a b c Nelida Fuccaro, p. 46ff

- ↑ Robert Dankoff (. Ed. And Translator): The intimate life of an Ottoman statesman: Melek Ahmed Pasha, (1588 to 1662); as portrayed in Evliya Çelebi's Book of travels (Seyahat-name). New York 1991, pp. 167-174

- ^ A b Austen Henry Layard: In search of Nineveh. Eighth chapter: With the yezidi or devil worshipers. ( Memento from January 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) PDF, 212 kB, accessed on November 23, 2009

- ^ The caste system of the Yazidis , accessed December 14, 2009

- ↑ Nelida Fuccaro, p 38

- ^ Franz Kandolf: Kara Ben Nemsi on Layard's footsteps. accessed on December 16, 2009

- ↑ Nelida Fuccaro, pp. 70-77

- ↑ Nelida Fuccaro, p. 110ff: Chapter IV, Tribes, Borders and Nation Building.

- ↑ Exact location of the village (GeoNames)

- ↑ a b Irene Dulz, Siamend Hajo & Eva Savelsberg: Persecuted and courted: The Yezidis in the "new Iraq". ( Memento of November 27, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) PDF, 215 kB, accessed on November 23, 2009

- ↑ Khalil Jindi Rashow: The Yezidis today ( Memento from August 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on December 2, 2009

- ↑ Names of the destroyed villages ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) PDF, 78 kB, accessed on December 2, 2009, text from: Mary Kreutzer; Thomas Schmidinger (Ed.): Iraq - From the republic of fear to bourgeois democracy? Freiburg 2004, pp. 197-204

- ^ Tilman Zülch: New suicide bombing in Iraq overshadows the memorial event of the Yezidi community in Germany. Report of August 14, 2009 (on the anniversary of the attack).

- ^ Kurdish Forces are Pushing Back Against ISIS, Gaining Ground Around Mosul , The Daily Beast, June 13, 2014

- ↑ Yazidis save themselves to the north ( Memento from August 10, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ General Sinjarite Information , accessed December 8, 2009

- ↑ Sinjarite, a new mineral from Iraq PDF, 188 kB, accessed December 8, 2009

- ↑ falconry in Iraq , ufgerufen on February 12 2018th

- ^ A b Steven Mithen: After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000-5,000 BC. Cambridge, Mass .: Harvard Univ. Press, 2006, p. 434

- ^ Association of German Zoo Directors: Halbesel , accessed December 8, 2009

- ^ Short note from the Paleontological Society. accessed December 8, 2009

- ↑ a b N. Ya. Merpert and RM Munchaev: The Earliest Levels at Yarim Tepe I and Yarim Tepe II in Northern Iraq. published in Iraq Vol. 49 (1987), pp. 1-36

- ^ Map of the settlements , accessed December 8, 2009

- ↑ Qermez Dere, Tel Afar: Interim Report No. 2,1989. PDF, 363 kB, accessed December 8, 2009

- ^ Mission archéologique de Sinjar , accessed December 19, 2009

- ^ Reinhard Bernbeck : Steppe as a cultural landscape. The 'Ağiğ area from the Neolithic to the Islamic period. With contributions by P. Pfälzner. Berlin contributions to the Middle East, excavations 1, Berlin 1993, see also short report. accessed December 8, 2009

- ^ Map of the sites , accessed on December 8, 2009

- ^ Central Assyrian Ceramics , accessed December 8, 2009