Austen Henry Layard

Sir Austen Henry Layard (born March 5, 1817 in Paris , † July 5, 1894 in London ) was one of the leading British archaeologists of the 19th century. He became famous for his excavations at Nineveh and Nimrud in Assyria . In the course of his life he had many professions: diplomat, politician, art connoisseur and writer.

family

Layard (pronounced "le-ard") was born on March 5, 1817 as the eldest of four children of Peter John Layard (son of a dean in Bristol) and Marianne Austen, (daughter of Nathaniel Austen, banker from Ramsgate ), who lived in 1814 in Married England, born in a Paris hotel. His ancestors were Huguenots who fled to England after the Edict of Nantes was repealed . At the age of 51, Layard married Mary Enid Evelyn Guest on March 9, 1869 (* July 1, 1843 - November 1, 1912), the daughter of Sir John Guest and Lady Charlotte Guest , a cousin and long-time friend of Layards. The couple had no children. Sir Henry and Lady Layard were buried in Canford Parish Church cemetery, next to Canford Manor in Dorset , which belonged to the Guest family (now a school).

Childhood and youth

Layard's father had worked for the Civil Service in Ceylon . Since he suffered from asthma , the family traveled across Europe in search of favorable climatic conditions. In 1821 Layard's parents left England and moved to Pisa , then to Florence . His father introduced him to literature and art from an early age. In 1825 he went to Moulins , where eight-year-old Henry attended a French school. After that they lived in Geneva , then again in Florence, so that Layard was now fluent in French and Italian. In 1829 he was sent to London, where he lived under the supervision of his uncle and aunt, Benjamin and Sara Austen, until boarding school in Richmond , which he left in 1833. January 1834 he became a clerk at his uncle's notary's office. For the sake of his uncle, he changed his name from Henry Austen to Austen Henry, but he allowed himself to be addressed as Henry for the rest of his life. In 1834 his father, who had since returned to England, died in Aylesbury .

On Sundays, Layard met interesting people in his uncle's house in Montague Square, such as the young Benjamin Disraeli and Charles Fellows , who had traveled through Greece in 1832. In 1835 Layard accompanied the painter and writer William Brockedon (1787-1854) on a trip to the Alps, on which they made the acquaintance of Count Camillo Benso di Cavour and his family.

Layard made his first trip at the age of 20 and little money: in 1837 to northern Italy, where he met Silvio Pellico and other important people. On another extensive trip to Scandinavia and St. Petersburg in 1838 , he met Christian Juergensen Thomsen (1785–1865), the founder of the Danish National Museum , in Copenhagen . Thomsen had developed a three-period system to divide the prehistoric period into the Stone Age , Bronze Age and Iron Age and led Layard through the newly established collection.

In 1839 Layard passed his final exam as a lawyer and realized that with his liberal outlook and political attitude (he sympathized with the Polish and Italian freedom fighters) he probably had no prospect of becoming a partner with his conservative uncle. Nor did he enjoy the legal profession. He was depressed and wanted to leave England.

First trip to the Orient (1839–1841)

He met Edward Mitford through his uncle Charles Layard, who wanted to travel to Ceylon to build a coffee plantation. Afraid of the sea, Mitford decided to travel by land through Europe, Central Asia and India and looked for a companion. Mitford suggested to Layard to accompany him on this trip and he saw it as the fulfillment of his childhood dream. He had read the publications of John Malcolm , who was the East India Company envoy to Persia, and of Claudius James Rich , who examined the great mound of Kuyunjik (Kuyundschik) in 1811. To prepare for the trip, they sought the advice of the Royal Geographical Society . He also came across a brochure from Major Henry Creswicke Rawlinson , whom he later got to know in Baghdad . Charles Fellows , who discovered the ancient capital of Xanthos (now Günük , southwestern Turkey) in Lycia in 1838 , and whose sensational finds were placed in the British Museum , gave them valuable advice. From a captain he learned how to use the sextant and from a doctor how to treat wounds, how to use a lancet and how to recognize the symptoms of diseases. This could only be done quickly, but it should be useful on his travels.

They agreed to travel as cheaply as possible, and the only luxury (according to Layard) was a "Levigne bed" to protect them from insects. Armed with pistols, a pocket sextant and compasses, and an advance of £ 200 from the publisher Smith & Elder on subsequent travel reports, they set out on their journey on July 10, 1839. Layard had also deposited £ 300 with a bank in order to have funds abroad.

They had several letters of recommendation and were of good cheer with their preparations. They traveled through the Netherlands and Germany. In Munich they met two Englishmen with whom they shared a carriage over the Brenner Pass to Venice . From there it went by ship to Trieste and on through Dalmatia . In Fiume they received further letters for Montenegro and entry into Turkish territory. At the end of September they were in Scutari ( Shkodra ) and asked the pasha there for permission to look after their horses at post stations. He also gave them various letters of recommendation for the transit to Constantinople . Now they were in the Orient. They rode to Bulgaria via Tirana and Monastir . Accompanied by a Tatar they went to Adrianople , and they finally reached Constantinople on September 13th. Here Layard suffered a fever attack and was treated by an Armenian doctor. He also showed him how he can drain himself. Lord Carnarvon visited him at his sickbed, and Mr. Longworth, the Correspondent for the Morning Post in Constantinople, cared for him so devotedly that a lifelong friendship developed. On October 4th Layard had recovered and they bought three horses to continue their journey. They reduced their luggage to saddlebags - but they never parted with their “bed”. They also hired a Greek who spoke French, Turkish and Arabic and served them as a cook and helper. Mitford and the Greek took the overland route while Layard got on a boat to take a rest. They met again in Mudania . They had received a firman from the Sublime Porte through the Consul General for traveling for foreigners on Turkish territory. All three wore the Turkish fez and European clothing, so that the Turks considered them to be officials from Constantinople. Via Konya and Karaman they crossed the Taurus with a guide and reached Tarsus . Having passed many historical sites, they both regretted that they had no historical or archaeological knowledge. They slept in hostels, with villagers or in the open air. On November 13th they left Tarsus for Adana to Antioch in Syria. They found support for their onward journey from consular officials everywhere. On November 28th they left Antioch for Aleppo , where they were guests of Mr. Charles Barker and Layard suffered another fever attack. In winter they shared the stable with their horses for the warmth. By now their horses had ridden through and they had to ride three mules to Tripoli .

In January 1840 they reached Jerusalem where they parted. Layard visited the ruins of Petra , Ammon and Gerash . He was attacked by Bedouins . They met again in Aleppo and traveled together to Mosul , where they arrived on April 10, 1840 and stayed a good two weeks. Here they met the French explorer Charles Texier , who was on his way home after having made numerous drawings and plans of Persepolis and Pasargadae . Layard writes: “We visited the great ruins on the east side of the river, which were generally considered to be the remains of Nineveh . We also rode into the desert and explored the hills of Kalah Sherghat , a huge ruin site on the Tigris , about 50 miles below the confluence with the Zab . We rested in the small village of Hammum Ali , which was surrounded by the remains of an ancient city. From the top of an artificial pile we looked down on a broad plain that was divided by a river. A line of towering hills rose to the east and one in the shape of a pyramid rose high above the rest. Beyond that, the Zab River could be faintly made out, which made it easier to pinpoint the location. This was the pyramid Xenophon had described. The winter rain made the hills green and after a careful search some ceramic fragments and inscribed stones were found in the rubble that had piled up around the great hill. However, we found no evidence of the "strange black stone figures" that the Arabs said should be there. At the time of our visit the country was deserted by the Bedouins and was only occasionally haunted by a few pillagers from the Shammar or Aneyza tents. "

The British Vice Consul, a local Christian ( Chaldean ), Christian Rassam , invited the two to a trip to the ruins of Hatra . Eventually they rented a boat to make the trip to Baghdad . Now they passed the hills of Nimrud from the waterside and Layard remembers: " My curiosity was aroused and since then I have wanted to examine these unique remains thoroughly whenever I should be able to ." In They stayed in Baghdad for a few months to visit the important ruined cities in the area - and especially the remains of Babylon .

In August they decided to cross the Zagros Mountains near Kermanshah to Persia . When they reached Kermanshah, they traveled on to Bisitun (also Bīsotūn, historically Behistun ) to see the local cuneiform rock inscriptions . There they met the French Eugène Flandin , who drew this monument and who would later work for Paul-Émile Botta . The English Colonel Henry Creswicke Rawlinson , stationed in Persia, discovered these inscriptions in the summer of 1835 and took an impression. Now they learned that they needed permission from the vizier in Hamadan to travel to Persia, which was not granted to them due to the Persian-British tensions at the time. However, you could travel at your own risk and with no guarantee of your safety. Mitford saw this as too risky, so they parted ways here and Mitford continued his journey to India. Layard rode now at his own risk into the mountains of Luristan and Chuzestan ; however, the hostility of the locals and an attack of malaria forced him to return.

With the Bakhtiars

Recovered, Layard went to Isfahan . The governor allowed him to cross the land of the Bakhtiars (Persian: Bachtiyārī), 107 km southwest of Isfahan. The Bakhtiars are the largest of all Persian tribes. Layard planned to travel on from there to locate the ancient city of Susa and then on to Persepolis in Fars Province . In September 1840 he moved with a caravan to Kala Tul, the stronghold of the Bakhtiars. He won the friendship of Khan Mehemet Taki and his family and stayed there under his protection for several months. Here he also learned Arabic. He dressed like a Bakhtiare and lived there as simply as she did.

In the spring of 1841 the Persian governor received the order to subdue the chief of the Bakhtiars, who was thinking of the independence of his area. A large tax sum was demanded from Mehemet Taki Khan, knowing that he could not afford it. The khan played for time and sent Layard to the Gulf island of Karak , where the British garrison was stationed, in the hope of support . He knew that the British had terminated their alliance with the Persians. It took Layard and his companions several days to reach the coast. There they learned that the British had no interest in interfering in the political affairs of the tribes. In the meantime Layard's guide had taken off with his horse, assuming that Layard would stay with his compatriots, so that he made his way back alone on a donkey. Khan Mehemet Take was now forced to submit and fled with his family. The governor offered him safe conduct and reinstatement. Mehemet Take agreed. However, when he entered the camp with his companions - Layard among them - he was immediately shackled. Layard managed to escape in a small boat and found his way back into the marshland to the hiding place. When the Persians demanded the surrender of the family and all tribal members, they decided to attack the Persian camp. Although they killed many Persians, the attack failed and they were forced to seek refuge with relatives in the Zagros Mountains. However, these were unfaithful and put the brother of the Khan Au Kerim and Layard in chains. However, the chief's wife helped them escape.

Layard now decided to return to Mesopotamia. It was the hottest time of summer now, and it took him several weeks to reach the Tigris near Basra . Fortunately for him, a British merchant ship was lying on the bank here, which, after some astonishment at the "ragged local", took Layard on board. After a short rest on the ship, he headed north to Baghdad. Although he was attacked and robbed several times, he reached the city gate, half-naked and with bleeding feet, where he passed out. He managed to get the attention of the British doctor Dr. To draw on Ross when he left town for his daily morning ride. It took Layard weeks before he could reasonably walk again.

In Baghdad he received mail from London. His uncle Benjamin had meanwhile gone bankrupt with his company in Ceylon and was not prepared to offer his nephew a future in London. Layard wrote a long report for the Royal Geographical Society about his experiences in Chuzestan (today's province of Khuzestan ).

In the end, it was his experience in Khuzestan that gave him a new beginning. The Persian campaign against the Bakhtiars and Marsh Arabs (Ma'dan) led to a major conflict with Turkey.

Constantinople in the service of Sir Stratford Canning (1842–1845)

Colonel Taylor, the British resident in Baghdad, would have liked to see England support the Turkish side and sent Layard to Constantinople to the British ambassador with appropriate reports. Layard interrupted his trip in Mosul, where he met the new French consul Paul-Émile Botta . Botta was commissioned to buy antiques for the Louvre , and he informed Layard of his intention to start excavations on the hills of Küyünjik, which lay across the river. Layard reached Constantinople in July 1842 and made his way to the residence of the British Ambassador, Sir Stratford Canning in Buyukdereh. Because of his knowledge of the situation in Persia, he asked him for a report that was to be sent to England. Sir Canning took a liking to Layard and paid him out of pocket. He gave him various unofficial diplomatic tasks in the European provinces of the Ottoman Empire, including traveling to Thessaloniki . Both men supported Turkey in the border conflict with Persia and equally progressive reformers in the Turkish upper class, a position that did not follow the prevailing policy of Lord Aberdeen's government in London.

During his time in Constantinople Layard received regular mail from Botta, who gave him news of his excavations north of Mosul in Khorsabad . The results so far have been spectacular, particularly the carved reliefs and statues of giant winged bulls with human heads. He urged Layard to take part in this project - but Layard had to refuse because he lacked the means and he had found nowhere support for his dream. However, Layard used the information received from Botta for some articles that he published in the "Malta Times" and which aroused great interest in Britain. The "Malta Times" was founded by Sir Stratford Canning to look after British interests in the Eastern Mediterranean. He also heard from Henry Creswicke Rawlinson , the new resident of Baghdad, who expressed an interest in Layard's experience. Rawlinson was fascinated by the oriental languages and occupied himself with deciphering the Behistun inscription .

Sir Stratford Canning, after difficult negotiations lasting over three years with the Sublime Porte, finally achieved in 1846 that 12 marble reliefs from Halicarnassus depicting the battle between Greeks and Amazons could be brought to the British Museum in London . Layard tried again and again to arouse Sir Canning's interest in an excavation in Nimrud and finally convinced him to support his plans. He received £ 150 for costs and a set of instructions from Sir Canning, who clearly saw Layard as his contractor:

"I rely upon Mr Layard's obliging attention to the following points:

|

"I rely on Mr. Layard's due knowledge of the following points:

|

He was equipped with travel documents from the embassy and with introductory letters for the authorities in Mosul and the surrounding area. Layard left Constantinople by steamer to Samsun (Black Sea) and rode on post horses over the Pontus Mountains (Kaçkar Dağları in Turkish) and the great steppe of Usun Yilak into the Tigris Valley. He galloped across the vast steppe of Assyria and in 12 days he reached Mosul.

Excavations in Nimrud 1845–1847

Layard reached Mosul in October 1845. In Mosul he handed over his letters to the governor of the province, Mohamed Pascha, without telling him the reason for his trip. He found support for his plans from the English merchant Henry Ross, who knew the country and its people, and the Vice-Consul Christian Rassam, on whose help he was dependent because he did not have a firman (official permit) from the Ottoman (Turkish) government for excavations . Rassam secretly procured the tools he needed, and Ross went on a “hunting trip” to Nimrud , where Layard followed by boat with the equipment.

Nimrud is located on the east bank of the Tigris, 37 km from Mosul in a southeastern direction. The ground plan of Nimrud is trapezoidal (600 m long; 300 m wide; the hills more than 20 m high) and covers an area of around 360 hectares, enclosed by 8 km of walls. The Acropolis is in the southwest corner and covers about 24 hectares. The Acropolis is called Tell by the Arabs , a mound of ruins piled up by the remains of hundreds, if not thousands, of its inhabitants.

Layard believed he was in Nineveh (h), but he was wrong. When he was later able to decipher some inscriptions with Rawlinson, it turned out that it was the city of Kalchu , mentioned in the Old Testament under the name "Kalah" (Genesis 10:11) and it is said that Nimrod , the mighty hunter, founded it.

They set up their first camp near the village of Naifa, from whose sheik they were warmly received, and who provided them with six workers. After a 20-minute walk they were at the ruins. A little later, fearing attack, they moved to Selamija, which was three miles from the hill of ruins.

On November 8, 1845, he began exploring the hill. The excavations were an instant success. His workers' shovels hit stone tablets with cuneiform inscriptions, and by evening they had exposed ten plates and hit room walls. With some people he started digging in the south-west corner where he had seen fragments of alabaster . Again he came across slabs with inscriptions and remains of walls. He realized that larger buildings had stood here, and he decided to follow his excavations towards the north-west corner. The next morning, five other helpers were there, and he had one group clear the rubble from the room while the other followed the wall to the south-west. Ivory objects with traces of gilding lay in the rubble of the room. Ahwad, his helper, warned him that the "gold find" could become known to the Pasha. On the third day he had trenches dug in the high, conical hill, but even here he found only fragments of brick with inscriptions. Now he ordered all his workers to the south-west corner, where the branching of the building promised more success. However, until November 13th they only found inscriptions, but no sculptures. On November 14th, Layard went to Mosul to see the pasha to inform him about his activities. The city was in a state of excitement. The British consul had bought an old building for the storage of goods, and the Kadi announced on the spot that the "Franks" intended to buy up Turkey. When the pasha presented him with a gold plate, Layard suggested that he appoint an agent who would take any precious metals that could be discovered into his safekeeping in Nimrud. He made no objection to continuing the excavations. In Mosul he then took some Nestorian Chaldeans , who had left the mountains for the winter, into his service and hired an agent to search various hills near the city for sculptures.

On November 19, Layard returned to Nimrud and now employed 30 workers. The Chaldeans were strong and could handle the hoe while the Arabs cleared away the rubble. They climbed ladders into the trenches.

On November 28, they came across two relief slabs in the southwest of the hill. On each plate, two bas-reliefs were separated by inscriptions. They showed a battle scene, warriors on chariots with horses shooting arrows. The lower part showed the siege of a castle or a city. The second record was pretty much destroyed. The horses of the two warriors were chiseled away from the upper part. The lower part showed a two-story castle with a woman pulling her hair. A river was shown with many bends and a fisherman pulled a fish out of the water. He was delighted to tell Sir Canning of his first find.

The pasha was now constantly causing trouble; he had the workers intimidated into leaving the camp. At Layard's audition, he hypocritically promised him support. Then he claimed that Layard was digging in a Muslim cemetery and had secretly erected tombstones, which in turn brought the Kadi to the scene. Finally he had the work stopped entirely. Layard wrote to Sir Canning urging him to get the firman so he could not be bothered again.

Layard buried the bas-reliefs, left some guards there and traveled to Mosul on December 19, where he learned that Mohamed Pasha had been deposed from the Sublime Porte and Ismail Pasha, a young major general of the new school, was to take over the official business. He decided to travel to Baghdad and talk to Major Rawlinson and inquire about the removal of his previous finds. When Layard returned to Nimrod on January 17th, he had recruited some Chaldeans again, and the ruins had turned green after the rain. He rented a hut on the plain in front of Nimrud and Hormuzd Rassam , the vice-consul's brother, joined him and took on the task of paying the workers their daily wages and looking after the domestic furnishings.

In mid-February he carefully resumed the excavations with some workers. He found more bas-reliefs with eagle (or vulture) heads when suddenly an excited Arab rode up and called out to him, "They have found Nimrod themselves". In the ditch they had exposed a huge human head. Layard saw immediately that this head must belong to a bull or a lion, as had been discovered in Khorsabad and Persepolis. The Arabs had been terrified by this apparition, and one had run straight to Mosul. Layard was able to get Sheikh Abd-er-Rahman to step down and touch the figure to see that it was made of stone. He said that it must be one of the idols that Noah cursed before the flood . So everyone was reassured and in the evening they all celebrated together. The next day, numerous onlookers from Mosul and the villages lined up, but they were not allowed to enter the trench. In the city, the Kadi, Mufti and Ulema had called on the population to protest to the governor because such undertakings were against the law of the Koran. Layard had difficulty making Ismail Pasha understand his find, so the latter asked him to stop the excavations until the excitement in the city subsided. Except for two, he now laid off his workers.

Meanwhile, Layard's funds were running out, and he made every possible argument, including culture, history and national pride , to Sir Canning, for the competing French had got a firman for Kujundschik. Canning, meanwhile, tried to get the British Government on board by writing to the Prime Minister, “My agent's work has been rewarded by the discovery of many interesting sculptures and a world of inscriptions. If the excavation keeps what it promises so far, then there is great hope that Montagu House (the British Museum) can beat the Louvre. ”During this interruption the Vice Consul Rassam invited him with his wife and several gentlemen from Mosul to visit the ruins of To visit Hatra .

At the end of March Layard was certain of the existence of two winged and human-headed lions, who once served as gatekeepers to this room, which has become famous as the throne room of King Assurnasirpal II . Kings, priests and warriors had passed through these portals. For 25 centuries they had remained hidden from people. The civilization and luxury of this nation were unimaginable. His two workers made slow progress in uncovering the lions. They turned to the wall and dug along it. Here they soon discovered a broken bull and under it 16 copper lions, in a sequence from big to small.

At the beginning of May, Ismail Pasha was transferred from Mosul and Tahyas Pasha came to replace him. This fine elderly gentleman allowed Layard to proceed with his excavations. In the early summer of 1846 the long-awaited letter from Constantinople finally arrived. It not only contained the permission to dig anywhere in Turkey, but also to transport the monuments to Europe. However, that did not solve his financial problems to hire more workers.

Courageous with the permission of the vizier, Layard now began to carry out trial excavations in Kujundzhik on the southern front, where the hill was highest. Here he immediately encountered the objection of the French consul, M. Guillois, who declared the ruins as French property because Botta had started the excavations there first. However, this was not recognized, so both Layard and Guillois dug there, but each in a different direction. When after about four weeks neither of them had discovered anything important, Layard went back to Nimrud.

Shipping of the reliefs and the lion

Layard now started shipping the reliefs and the lion. He had discussed with Rawlinson in Baghdad to send the steamship "Nitocris" to Mosul. The engine was too weak, however, and the ship had to turn around at Tikrit . The first difficulty was to move the reliefs with their considerable weight. He had as much of the remains of the wall removed from the back as possible. Since the inscriptions were the same on all of them, Layard simply had them cut out by marble cutters from Mosul. The two halves thus obtained were transportable. Now they could be pulled out of the trenches. The heads of a king with his eunuchs , an eagle-headed deity and the head of the bull made of yellow limestone were wrapped in felt and mats in raw wooden boxes. They were taken to the river in simple buffalo carts that belonged to the Pasha and then loaded onto a kellek, a raft made of puffed up animal skins. The Tigris is navigable from Mosul on, has a considerable width and depth, but also many rocky cliffs. At Al-Qurna ( Korna ) it unites with the Euphrates to form a single river, the Shatt al-Arab . There it is then navigable for large ships, but the entrance at the mouth was made very difficult by sandbanks.

Through Kurdistan and with the Yazidis

Due to his poor health, Layard decided towards the end of August to stop the work and escape the heat. He made a detour to Khorsabad, where Emile Botta had finished his excavations. He found that Botta had proceeded in a similar way to his own in Nimrud and that the rooms were smaller. The construction and the material were also the same. Since Botta's departure, the trenches had partially buried the rooms again. It could be seen that large parts of the palace were burned, only one staircase was solid masonry. Khorsabad was a humid, swampy area because of the Khausser River and its numerous small tributaries, and many workers had fevers.

Accompanied by Hormuzd Rassam and some servants, they rode into the Tiyari Mountains northeast of Mosul - through Kurdistan - as many of his Nestorian workers had come from there. The Nestorians were a Christian sect that had long lived in this region. Here they also found out about the massacres by the Kurds in some villages. In some areas they met Chaldeans who had since converted to the Roman Catholic faith.

A few days after their return to Mosul, Layard and Mr. Rassam, the vice-consul, received an invitation from Sheikh Nasr, the head of the Yezidi , to attend a festival. He was warmly welcomed there and given the great honor of visiting the tomb of Sheikh Adi , the great mystic of the 12th century. It was located in a former monastery in Lalisch and was visited by many pilgrims once a year. Little was known about their religion and Layard was one of the few outsiders to witness their rituals. He was the first European to report extensively on the Yazidis in Sheikhan and the Jabal Sinjar , whose "Feast of the Assembly" (Jashne Jimaiye) he was able to experience in Lalisch .

They suffered greatly from the last pashas and were suspicious of the Turkish authorities. Layard witnessed a campaign in the Sinjar - mountains , where the Turks attacked the capital of the Yezidis and the old people who were left behind to defend executed him. The remaining residents had barricaded themselves in a ravine and were vehemently defending themselves. The Pasha's troops attacked their position several times, but were defeated with heavy losses.

British Museum Commissioner

Back in Mosul he received a letter from the British Museum appointing him as their agent and providing him with funds of around £ 1,000. Sir Canning donated the sculptures discovered in Assyria to the British nation. Layard was deeply disappointed by this stinginess, because the amount was in no way sufficient for the upcoming work, especially since the transport costs were also included in this sum. He also received a long document from the trustees detailing his responsibilities and informing him that they would not be able to promise him any further employment once his work in Iraq was finished. This news was another blow for him.

Many of the monuments discovered were in a state of imminent decline, so that they could not be transported. Only through drawings could they be preserved for posterity and he was very resentful that no artist had been promised to support him. He therefore had to supervise the excavations, draw all the bas-reliefs that were discovered, copy the countless inscriptions and make impressions of them. The impressions were made with brown paper that was moistened and pressed onto the plate with a stiff brush. Some of these impressions served as molds and were later cast in plaster of paris in England. For this purpose, the paper was made into a kind of pulp and mixed with a slimy powder that comes from a root called "Schirais". Furthermore, he had to pack the finds and supervise all work so that no damage was caused to the monuments during the excavations. Layard said (probably not wrongly) that if someone were to be sent from England who also spoke the language, he would have spent the amount granted in his negotiations with the Turkish authorities, residents and workers before the excavations had even started would be.

The warehouse

Layard now looked for 50 workers, strong Chaldeans, a skilled marble cutter, a carpenter and Mohammed Agha, whom he had met as a standard leader, to supervise. His kawass , Ibrahim Agha, also returned to Nimrud with him at the end of October. Outside the village he now had a two-room mud-brick house built for himself. The roof was made of beams with branches covered with mud to keep out the rain. He also had an open courtyard built and everything surrounded by a wall. More huts were built for his kawass, servants, guests and horses. On the hill of ruins itself, a house was built for the Nestorian workers and their families, as well as a hut in which the small objects discovered in the ruins could be brought for safety reasons. According to the tribes to which the Arabs belonged, Layard divided them into three divisions. Around 40 tents were pitched at various points on the hill, especially at the entrances to the trenches. There were more tents around Layard's house and on the river bank, where the sculptures were to be placed on rafts before shipping. Almost all men were armed so that they could defend themselves in the event of a Bedouin attack. Hormuzd Rassam lived with Layard. He soon got a great influence on the Arabs and his reputation spread through the desert.

Layard divided the workers into sections: 8 to 10 Arabs who carried the earth away in baskets and 2 to 4 Nestorians to dig. He mixed with the Arabs some of a hostile tribe so that he would know immediately if a plot was being forged or someone was trying to acquire something from the excavations. An overseer was overseeing the squad and was instructed to notify Layard as soon as they came across a slab or small object.

More discoveries

On November 1st, Layard resumed his work and concentrated his forces in the northwest and in the middle of the area, where he had already made out parts of buildings. His workers were scattered all over the hill. They worked in rooms B, G and I (see Plan III), in the middle of the hill, near the gigantic bulls in the southeast corner, where no trace of a building has yet been found and by walls a and d (see Plan II). For cost reasons he continued the work as before, i. H. To continue trenches on the sides of the walls and expose the slabs without removing the earth from the center of the room, so that only a few rooms were fully examined. He was also instructed to fill up the building again after the examination. So he filled the rooms with the rubble of every new row he dug. A large number of panels were discovered in room B, which were well preserved and which Layard had immediately prepared for shipping. (Plates 13 and 14, 18, 19, 20, 21 and 22, 26, 27 and 30 in "The monuments of Nineveh") In room I they discovered a large amount of copper and iron as well as helmets and armor. They found broken alabaster vases under fallen plates. Now they also found three preserved vases with the inscription of the King of Khorsabad on them. There was also a glass vase - probably from Egypt (these pieces got lost in later Bombay , which Layard regretted very much.)

In the center of the hill he had discovered the gigantic bulls ( lamassu ), which appeared to him as the entrance to a building, and he continued digging around them. He dug deep trenches at right angles behind the northern bull. After about 3 m they hit huge slabs (No. 7). The trench had been continued for several days and was now about 50 feet long without leading to the slightest discovery. He was in doubt whether to continue when he discovered a piece of white marble that turned out to be part of an obelisk lying on its side 10 feet below the ground. When they exposed it and pulled it up the next day, Layard could see it. The obelisk was well preserved and none of the inscriptions were missing. It was flat at the top with three steps. There were five sculptures on each side - a total of 20, separated by inscriptions. The king was depicted twice. Vizier and eunuch bring people who lead different animals: camel, rhinoceros, lion, elephant, monkey and carry objects. Layard concluded from this that it was tribute payments. He could not have known that it was Jehu the king of Israel.

At the same time, a pair of winged lions was discovered in the southeast corner, but their tops had been completely destroyed because they were made of coarse limestone. Between the lions that formed the entrance were a pair of crumbling sphinxes . The entrance was completely buried under charcoal and the alabaster was calcified so that it shattered immediately when exposed to the air. Two other lions that had been exposed to the fire were also only in pieces. The layout and nature of the building remained a mystery to Layard. While digging further behind the lions, he discovered a few lines of cuneiform writing, from which he deciphered the names of three kings in a genealogical sequence.

In the southwest corner there were finds of a very different kind. Layard had excavated to a considerable depth without finding any traces of a building. A plaque was found with an inscription that Layard had seen as the same as on the bulls in the center of the hill. When the plate was erected, it was found that there was a sarcophagus underneath with a well-preserved skeleton, but it fell to pieces immediately when exposed to the air. Inside were two red clay jugs and a small alabaster bottle. Shortly afterwards they found a second sarcophagus with similar burial objects. Layard writes: “The six weeks since the start of the excavations on a grand scale have been among the happiest and most fruitful of events since my research in Assyria; almost every day brought a new discovery ” .

By April 1847, he had excavated 28 halls and rooms in the Northwest Palace alone , which were decorated with reliefs and with 13 pairs of winged bulls or lions. Now it was time to take a break.

The shipping of the gigantic figures

Layard began organizing the shipment, down the Tigris to Baghdad and then to Basra and finally to England. For this he needed many meters of rope and mats and these had to be imported from Syria. When a load of Bedouins was stolen, Layard rode into the camp with some Turkish policemen, where they immediately noticed the new ropes on the sheikh's tent. When the sheikh denied having the cargo, Layard handcuffed him and had him taken away. The next day, Layard received his goods back from the tribesmen.

On March 18th the bull was ready. Felt mats should prevent the ropes from chafing or damage if they fall down. The main difficulty was lifting the great mass. Layard followed the method Botta had used for transportation and was even able to use some of his ox carts. Tree trunks served as levers. Then the sculpture should be placed on "rollers", that is, rolling tree trunks to move it in the ditch. In addition to his workers, he received help from the Abu Salman tribe and the residents of the villages of Naisa and Nimrod. The family members had come to watch. Drums and whistles as well as the war cries of the Arabs accompanied the action, so that neither the overseers with their hippopotamus whips - let alone Layard - could make themselves heard. The dry ropes and ropes squeaked as soon as they felt the tension. They were doused with water, but in vain. The sculpture was only 1 to 1.5 m away from the rollers when the ropes broke. The bull fell down, and with it many Arabs who pulled the ropes. Layard feared the bull had been crushed. Fortunately that hadn't happened, and he'd also fallen into the position he needed. The Arabs were also unharmed and immediately after the shock began a wild dance. As soon as they had calmed down, a new attempt was made and the sculpture dragged out. Longitudinal sleepers were laid to the end of the trench and rollers were pushed under again and again. As the sculpture moved forward, the rollers that had become free at the back were put back under and after a short time it reached the end of the ditch. In the evening a festival of joy was celebrated and the next day work continued.

At the sloping point of the hill, the bull was brought down by removing the earth and laying the tree trunks. Soon the figure could be placed on the wagon by lowering it. Buffalo oxen were harnessed - but they refused to pull the load. Now manpower was needed again and in groups of eight the strongest took turns on the drawbar, while around 300 people pulled the car and screamed with all their might. In the abandoned village of Nimrud, two wheels got stuck in a ditch, although Layard had carefully examined the route beforehand. In these trenches, grain, barley and straw were kept for the winter and they were only sparsely covered. Your attempts to get the car afloat again were in vain. Layard left a detachment of Arabs to guard them, who were attacked promptly that night and a bullet nicked the bull's side. The attackers were, however, driven away. The next day they managed to free the bikes and the procession continued towards the river bank. Here the wheels dug into the sand and planks had to be laid out. A platform had been set up on the bank from which to slide down onto the raft. The Arabs set up their tents around the bull to guard.

Now the winged lion near room Y had to be brought to the river in the same way. The preparations for this were finished in mid-April and Layard now used twice the number of ropes. He had decided to lift the lion onto the wagon at once and not first drag it through a ditch on rollers. Since the lion had jumped in several places, it had to be taken down and transported with particular care. The Arabs gathered again as they did when the bull was being transported and everything went splendidly. They only needed two days for the transport to the river, because the wheels of the cart repeatedly sank in the sand.

This time Layard wanted to ship his sculptures beyond Baghdad directly to Basra on the rafts ( keleks ) . In Mosul, however, no raft guide could be found willing to do so. A man was finally found in Baghdad through an intermediary who was threatened with guilty prison and therefore agreed to take the trip. This Mullah Ali arrived in Nimrud and Layard had to deal with him about the construction of the raft. Because air gradually escapes from the skins, they have to be checked and the air topped up. This had to be done in Baghdad. So that the raftman could get to the openings in the skins, Layard demanded that the bull and lion be as high above the water as possible so that they could crawl under it. Layard needed 300 skins per raft. During the spring floods, small rafts could travel to Baghdad in 84 hours, but the large ones took at least 6 to 7 days to travel. Layard reckoned 8 to 10 days because of the heavy load. On April 20, Layard wanted to attempt the shipment. The two sculptures were placed on beams in such a way that as soon as the wedges were knocked away from under them they could immediately slide down into the middle of the raft. For this purpose, the high bank was cut into a steep sloping surface right up to the edge of the water.

But suddenly Hormudz Rassam appeared with bad news: the Arabs refused to work and asked for more wages. Layard knew that one or two leaders of the Jerbur were the initiators and were trying to get more money from the workers themselves. He had her arrested and told the others to leave the camp. A delegation of some sheikhs appeared expressing concerns about Layard's safety. He countered this hidden threat by putting his homestead into a state of defense and opening the loopholes in the wall. The sheikhs had pitched their tents within sight of the village and many had to follow them. Layard immediately sent a messenger with a letter to Abd-er-Rahman asking for help. In the evening this loyal friend appeared and he sent an order to his tribe not to continue the march and to return in the number Layard required. When the Jerbur saw the Abu Salman Arabs approach, they came back to Nimrud to resume their services. Layard didn't listen to them, however.

The poplar wood beams laid on the inclined plane were now lubricated with a lubricant. Layard saw the only difficulty in the fact that the sculpture slid down too quickly and the pressure shattered the skins of the raft. The Arabs had to prevent this on the ropes. Everything went as planned, so that a second raft of the same size could be brought up for the lion. Here, too, everything went according to plan.

Now there were still many panels, including the large bas-relief, which depicts the king between the eunuchs and winged figures on the throne and which had formed the end of room G, as well as the altarpiece from room B and over 30 boxes, which the smaller ones in the ruins discovered items contained to distribute on the two rafts.

When the work was done, Layard gave a feast for Abd-er-Rahmann and his people, as well as for everyone who had helped him with the loading of the sculptures. Then they said goodbye.

On the morning of the 22nd, Layard gave each of the rafters a sheep, which they sacrificed on the bank for a happy journey. After all the ceremonies were over, Mulah kissed Ali Layard's hand, sat on a raft, and then went down the Tigris.

According to the instructions of the directors of the British Museum, it was Layard's last job to fill the excavated rooms with earth again so that the sculptures still in them were not damaged by wind and weather or destroyed by hostile Arabs.

Nineveh - Kujundschik

Because the Arabs from the desert had set up camp on the west bank of the Tigris and Layard feared their attacks, he left Nimrud and traveled to the great hill of ruins at Kujundschik . From the villages in the neighborhood it was reported that these ruins were an inexhaustible source of building material and Layard was curious to see if any building still existed there.

Nineveh is dominated by two approximately 20 m high ruin mounds. The northern one (800 m long, 400 m wide) is called Kujundschik , the southern one is popularly called Nebi Junus after a mosque built on it and dedicated to the prophet Jonas. This place was sacred to the believers.

The Arabs pitched their tents by the trenches. Here men and women found space for their daily ablutions. However, they got drinking water from the Tigris. Layard lived in the village. He knew that when the Assyrians built a palace or a public building, they built platforms of sun-dried adobe bricks 30 to 40 feet (about 9 to 12 m) above the level of the plain. The monument was erected on top of it. If the building was destroyed, the ruins remained on the platform. So he looked for platforms. Because Kjundzhik was very buried, he had to dig deep, starting in the southwest corner. Fragments of alabaster were found. Finally, the remains of an entrance and a slab that had been completely destroyed by the fire were found. From the inscriptions on the plates, Layard could infer that - according to those found in Nimrud - this must be the son of the builder of Khorsabad, or his predecessor or successor with whom he was in direct contact.

He had soon excavated part of the Southwest Palace in Kuyundzhik and was convinced that a continuation of the investigations in Kujundzhik would be rich in interesting and important results. Layard had little money left, so he left Mosul on June 24, 1847. Hormuzd Rassam, his right hand man, accompanied him to England

Layard's triumph in London

Layard's return to Europe was overshadowed by the revolution that shook Europe in 1848. He had been informed of an open position in the Foreign Office and he was supposed to be waiting for Sir Canning in Constantinople. Layard suffered another attack of malaria, and when Sir Canning's return was delayed, he went to Italy in the fall to visit old friends and the ruins of Pompeii . His onward journey took him to Paris, where Botta received him with open arms. The Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres invited him to give a lecture and they congratulated him on his work. Botta himself had expected that he would be sent back to Mosul as a French consul, but the political events in France prevented that. Instead, he was given a small post in Jerusalem. The two men should never see each other again.

He hurried to London, where he arrived at his uncle's house in Montague Square in December 1847. He quickly got in touch with his employer, the British Museum. The first shipment from Nimrud had arrived and the pieces were already on display, although a few boxes were still waiting for shipment on the quayside in Basra. He still needed rest to recover from the exhaustion and repeated attacks of malaria that had made him very debilitated.

The Foreign Office finally found a post for him - as a member of an international border commission to determine the borders between Turkey and Persia. He wasn't really ready to travel to the Middle East again anytime soon, because he found joy in his new fame and the dinner parties it brought with it. Arrangements were made to publish his drawings and texts together with a narrative of his excavations. The museum was reluctant to fund further excavations, especially since Layard wanted £ 4,000 to £ 5,000 for the first year alone - which was viewed as completely unrealistic.

The 1840s were a tumultuous time and the effects of the industrial revolution on society were varied and writers such as Disraeli and Dickens (Marx and Engels worked on their "Manifesto") addressed these issues. Ireland had just experienced the Great Famine (Potato Famine) and the Chartist movement was calling for political reforms in Britain. On the continent, the February Revolution in Paris was followed by similar outbreaks in Germany, Italy and Austria-Hungary. The government had more pressing business than archaeological expeditions to the Middle East.

The Victorian era was still class conscious and Layard had no powerful relatives to advance his interests. Among his many loyal supporters during this period was his cousin Charlotte Guest , who arranged the contract with publisher John Murray . She was married to the wealthy industrialist Josiah John Guest, to whom she bore five sons and five daughters. She had a variety of interests, learned several languages during her pregnancies, and took an active role in her husband's business. She was busy furnishing her home, Canford Manor, and Layard gave her some reliefs for decoration. (One of these reliefs was discovered in 1992 and sold by Christie's to the Miho Museum near Kyoto in 1994 for £ 7.7 million (US $ 11.9 million).) It in turn encouraged him to speed up the description of his discoveries.

Layard lived with his mother in Cheltenham and spent the whole of 1848 writing. He resigned from his post on the Borders Commission in September. At about the same time, the boxes with most of the unearthed finds arrived in London after they had already been exhibited in Bombay, where they had to wait several months for shipping. When he unpacked them, however, he was disappointed to find that they had been repackaged carelessly and that most of them had broken. His records of the localities were all mixed up and many of the smaller pieces were gone.

In the spring of 1849 his book Nineveh and Its Remains came out. John Murray cost about £ 7 to edit Nineveh and its remains , but £ 300 for the master engravers who turned Layard's drawings into hundreds of eye-catching illustrations. Due to the great success it became a profitable bestseller for everyone, which was translated into many languages. (A year later, John Murray edited The Monuments of Nineveh .) Layard was now receiving praise from all sides. The President of the Royal Asiatic Society called the book "the greatest achievement of our time" and even his uncle Benjamin was impressed. The University of Oxford awarded him an honorary doctorate in civil law DCL (Doctor of Civil Law). There was great interest in renewed excavations in Assyria - and especially in Kujundschik.

For the trustees of the British Museum, Layard edited a volume containing the copies of the inscriptions of Nimrud, Kujundschik (Nineveh), Kalah Shergat ( Assur ) and other Assyrian ruins. This publication, as well as the cuneiform scripts discovered by Mr. Botta in Khorsabad in 1842, provided a wide range of material for research. A few eminent orientalists and linguists took on the matter, including Edward Hincks , Edwin Norris (Secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society), William Henry Fox Talbot and Julius Oppert . Sir Henry Rawlinson announced in 1850 that he had succeeded in deciphering the inscription on the black obelisk that Layard had discovered in Nimrud.

Second research expedition from 1849 to 1851

Layard had taken up his post in Constantinople as an attaché at the embassy in the summer of 1849, when, after a short time, the trustees of the British Museum told him that he could continue with the excavations in Assyria. The museum agreed to finance two more years (but for the stingy amount of £ 3,000). This time the artist F. C. Cooper was to assist him with the drawings. He immediately notified Hormuzd Rassam, who was studying at Oxford, and he also took with him the English doctor Humphrey Sandwith, who had traveled the east and was just in Constantinople. At the end of August they set out on a trip to Mosul together.

The very next day he rode to Kujundschik, where his friends Henry Ross and Christian Rassam had been digging after his departure. The trenches in the southeast corner were still open, where he had examined two more rooms (see Plan L I). However, the bas-reliefs were defaced. Toma Shisman, the overseer, had invented a very special technique: he penetrated through tunnel excavations to the palaces with their reliefs hidden under enormous masses of clay and rubble. He had a shaft dug a few meters down until it hit solid ground and from there worked his way through the tunnel laterally until it hit a wall. After that it was relatively easy to follow this wall and then dig through doorways from room to room until the whole complex was exposed.

Unfortunately, the Assyrian palaces were built of adobe bricks that had dried (burned) in the sun. This material is not easy to see for the untrained eye, so workers broke through many walls without being aware of it. But that also meant that the center of the room was not excavated.

Layard went down into the underground tunnel and visited rooms L XII and the great hall XIV with the portal, which was flanked by two huge human-headed bulls. There were relief panels everywhere showing war, capture and victory. These reliefs completely covered the slab and were not divided like those found at Nimrud. They also showed much more detail in the background. You could make out orchards and vineyards (the Levant ?), Mountains in the west or swamps in the south. Layard got the impression that they were telling stories.

Word of his arrival in Mosul quickly got around and he was able to reinstate many of his old workers, such as the marble cutter, carpenter and supervisor. He reinstated Toma Shisman as overseer of the work in Kujundschik and the Sheikh of the Jebour, Ali Rahal, became "Sheikh of the Hill". After two days, the Chaldeans from the mountains and the Arabs from the surrounding area also poured in. On October 12th, he was able to resume excavations. Over 100 workers, divided into groups of 12 to 14 people, were employed on the hill.

On October 18th he rode to Nimrud with Hormudz Rassam. On the way there they had to greet old friends everywhere. The pasha's troops were insufficient to stop the Bedouin raids, so the residents still lived in fear. He inspected the north palace and saw a few corners of reliefs or sculptures protruding from the subsided earth. The Southwest Palace was uncovered as he had left it. These were the signs of good guard by the residents who tilled their fields on the hill.

In Nimrud, too, he gathered his old workers to continue the excavations of the Northwest Palace. New trenches were opened at the central palace in the middle. The tell - or the pyramid - in the northwest corner had not yet been examined. With the exception of a shaft about 40 feet (about 12 m) deep, which was pretty much in the middle, nothing had happened here. Layard ordered a tunnel to be driven into the rubble on the west side of the base of the rock he was lying on.

Abd-er-Rahman's nephew appeared with some of his men because he had heard of people who were busy on the hill and wanted to see that things were going well. The joy of reunion was great. A day later he found Henry C. Rawlinson sound asleep in one of the excavated rooms. Since this had a fever, Layard accompanied him to Mosul and three days later Rawlinson traveled on to Constantinople.

During the months of November and December Layard was alternately in Kujundschik and Nimrud. Mr. Cooper, who lived in Mosul, rode to Kujundzhik every day to draw the bas-reliefs found. Hormuzd Rassam, who usually accompanied Layard on his rides, was the supervisor. He took care of the payment of wages, settled disputes and did many other tasks. He was an important man who knew the character of the various Arab tribes very well and was accordingly able to deal with them well. Layard emphasized: “The trustees of the British Museum not only owe him much for the success of these ventures, which he made possible for me through his profitability. Without him, I "would have achieved with the resources made available to only half. .

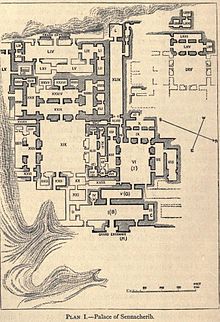

At the end of November the great hall (or courtyard) was excavated. This yard was 124 feet (37.80 m) long and 90 feet (approximately 27 m) wide (No. VI in Plan I). In the middle of each side was an entrance guarded by bulls. The walls were completely covered with reliefs that had suffered badly from the fire. A narrow corridor led to the southwest corner, which Layard had examined on his first visit. Many of the fire-attacked reliefs were left in place and Cooper and Layard only made drawings. Of some, only the lower part was preserved. The corridor led into a room 24 × 19 feet (7.3 × 5.8 m) from which further corridors (No. XLVIII and XLII in Plan I) branched off. This was the entrance to a wide and expansive 218 by 25 foot (66.5 by 7.6 m) gallery. A tunnel was carved on the west side because there was no entrance that led to the rooms that Mr. Ross had excavated and thus established a connection. The entire gallery had reliefs. Particularly interesting were those on the west side, which show the transport of the bulls that guarded the gates into the palace. Apparently they had already been roughly chiseled in the quarry and pulled on sleds to the river, where they had been loaded onto keleks and shipped to the palace. This is where they got the finishing touches and were then pulled into their final position. One of the reliefs shows the figure upright on the sledge, held by men with ropes and forked wooden props. It was held up by trees held together by crossbars and wedges, supported by blocks of wood or stone. On the sledge, in front of the bull, was an officer who was giving orders to the workers with outstretched arms. Ropes, pulleys, ropes and levers were used by the workers. The method was similar to that used by Layard and Botta when they removed the bulls and shipped them to Europe.

In Kujundschik a room was discovered (XXXVI, Plan I) 38 × 18 feet (11.6 × 5.5 m) in size, which uncovered relief panels in very good condition. It should turn out that this up to 2.50 meter high and 18.90 meter wide relief is about the conquest of the Judean city of Lachish . Lachish refused to pay tribute to the Assyrian King Sennacherib and was therefore destroyed. The Lachish relief clearly shows the events of the battle:

- There is heavy fighting in front of the walls, and heavily armored rams are pushed against the city wall on a siege ramp

- The defense tries to set the ramrods on fire with torches, at the same time the Assyrians pour water over the ramrods

- prisoners are taken, the dead are impaled, the booty is carried out, including the sacred vessels for religious rituals

- the topography and even the native flora are accurately represented.

"The chambers of records" - the archives

Inscriptions on cylinders (clay kegs or cylinder seals)

Surprising finds awaited him in Kujundschik. The first entrance, guarded by fish priests, led into two small rooms that opened to each other and were once decorated with bas-reliefs, but the greater part of which had now been destroyed. Layard called these rooms "the chambers of records" (nos. XL and XLI in the plan) because it seemed to him that they contained decrees of the Assyrian kings and the archives of the empire. The Assyrians' historical records and documents were kept on tablets or cylinders made of clay. Many specimens have been brought to England. Layard had sent the British Museum a large hexagonal (hexagonal) cylinder with the Chronicle of Assurhaddon on it. A similar cylinder discovered in Nebi Yunus shows eight years of the annals of Sennacherib . On top of a barrel-shaped cylinder known as a "Bellino" is another part of the records of the same king. The importance of these relics is easy to understand: they represent, on a small scale, an abbreviation or summary of the inscriptions on the great monuments and palace walls, giving a chronology of the events of each king's reign. The font is small and the letters are so close together that it takes considerable experience to separate and copy them.

The clay tablets - Assurbanipal's library

These rooms appeared to be a warehouse for such documents. They were filled with clay tablets up to a foot high (some later writers suggest that Layard was exaggerating here), some whole, but the greater part broken. They were of different sizes; the largest panels were flat and measured approximately 9 by 6.5 inches; the smaller ones were slightly convex, and some were no more than an inch long, but written on with a line or two. The wedge-shaped letters on most were uniquely sharp and well delineated, but so small that in some cases it was barely possible to read them without a magnifying glass. They had been pressed into the moist clay with an instrument, which was then baked. The documents were of various kinds: mainly reports of wars and distant expeditions undertaken by the Assyrians, as well as royal decrees stamped with the king's name. Lists of gods and probably the gifts that were offered to their temples, prayers. Letters in tables with bilingual or trilingual language; grammatical exercises, calendars, lists of holy days; astronomical calculations; Lists of animals, birds and various objects, etc. Many are sealed and turn out to be treaties or assignments of land. Still others have the impression of cylinder seals . On some tablets there were Phoenician or italic Aramaic letters and other symbols.

The adjoining rooms contained similar relics, but in much smaller numbers. Many boxes were filled with these tablets and sent to the British Museum. Layard did not yet know that he had found a large part of the Aššurbanipal library . Here he laid the foundation stone for the museum's famous “K” (ujundschik) collection, which was expanded to include other finds by Hormuzd Rassam, George Smith and others. Scientists are still busy assembling and identifying the fragments of these clay tablets like in a puzzle.

Under the clay tablets there was a fragment with the (today's) dimensions:

Length: 15.24 centimeters

Width: 13.33 centimeters

Thickness: 3.17 centimeters.

Twenty-two years after the 26,000 cuneiform tablets in the Assurbanipal library have carefully packed and completed their long journey from Nineveh to the British Museum in London, not all tablets have been deciphered by a long way. In 1872, in the dusty atmosphere of the British Museum, George Smith was busy deciphering more of these tablets.

In doing so, he discovered the world-famous Gilgamesh epic , the story of the legendary King Gilgamesh of Uruk , who set out to become the ancestor of the Utnapishtim human family in search of immortality. One point, however, particularly fascinated Smith. It is the description of Utnapishtim's miraculous rescue from a great flood. As the 11th panel “The Flood” of the “ Gilgamesh Epic”, it would later become world famous.

The eleventh panel tells of the flood and Utnapishtim. The Council of Gods decided to submerge the entire earth to destroy humanity. But Ea , the god who made man, warned Utnapishtim from Shuruppak , a city on the banks of the Euphrates, and instructed him to build a huge boat ( Noah's ark in our Bible ).

The seal

Along with these tablets, they discovered a number of fine pieces of clay that gave the impression of seals and which were obviously attached to documents written on leather, papyrus, or parchment. The documents themselves were gone. The holes for a ribbon or strip of animal skin to which the seal was attached can still be seen in the clay seals. Ashes remained in some of them and the thumb or fingerprint that had been used to form the hollow.

Most of these seals were Assyrian, but some bore Egyptian, Phoenician, and other symbols and signs. Sometimes a few prints of the same seal were found on a piece of clay. The most common Assyrian was that of the king, who killed a lion with a sword or dagger and was often surrounded by an inscription or a patterned border. This seemed like a royal seal.

The most important and notable discovery was a piece of clay that contained the imprint of two royal logos, one Assyrian and the other Egyptian. The Egyptian depicted the king killing his enemies. The name, written in hieroglyphics in the usual royal cartouche, was that of Shabaka of the 25th Egyptian dynasty . This king ruled Egypt towards the end of the 7th century BC. Around the time Sennacherib took the throne. Layard suspected that these seals were attached to a peace treaty between Assyria and Egypt.

The seal cylinder of the Sennacherib was later discovered at the foot of the large bulls that guarded the entrance of this palace. In the heap of ruins at the feet of one of the bulls, four "cylinders" (clay kegs that are hollow inside and are rolled onto a damp clay tablet, hence also called rolling cylinders) and some pearls with a scorpion made of lapis lazuli, which probably once belonged to a chain. He found the king engraved on a cylinder made of clear feldspar , standing in an arch like the rock relief by Bavian . Layard concluded that this must be the seal or an amulet of Sennacherib. In one hand he holds the holy scepter and the other is raised in adoration in front of the winged figure in a circle, which is shown here with three heads. This depiction of the emblem is very rare. The mystical human figure with wings and tail of a bird, framed by a circle, was the symbol of the Triune God, the supreme deity of the Assyrians and the Persians, their successors in the empire. In front of the king is a eunuch and the sacred tree , the flowers of which in this case have the shape of an acorn. A mountain goat is standing on a flower that resembles the lotus, closes the picture. The indentation on this beautiful piece of jewelry was not deep, but it was sharp and distinct, and the details are so tiny that a magnifying glass is necessary to see them.

In Nineveh they had uncovered the imposing entrance, which was flanked by a monumental facade with huge winged bulls and figures - similar to those that Botta had found in Khorsabad. This was the entrance to the throne room, which was on the west side of the great courtyard.

The bulls were more or less destroyed. Fortunately, however, the lower part was preserved by all. Because of this, we owe Layard the discovery of the most valuable ancient world records which rewarded the work of the archaeologists. The inscriptions of the large bulls on the entrance portal were consecutive and consisted of 152 lines. There were two inscriptions on the four bulls of the facade, each inscription was executed over a pair and the two had exactly the same meaning. These two unambiguous records contain the annals of six years of the reign of Sennacherib , that is mainly his victories, but also many details relating to the religion of the Assyrians, their gods, their temples and the construction of their palaces, all of the greatest interest and Are important for understanding that time. The names Hezekiah appear in it, as well as Sargon and Shalmaneser .

When they dug directly into the "Tell" in Nimrud, they uncovered an underground passage (30 × 2 m) that had been built a long time ago, probably by robbers, as another function was closed to them. Layard imagined the “pyramid” as a step-shaped tower, known as the “ ziggurat ”. He came to this by comparing it with a relief found in Nineveh . He estimated the height of the original to be 100 feet (about 30 m). Most of the burned bricks found in the rubble were named Sennacheribs.

After returning from Arban and the Kabur area on May 10th, he was told that torrential rains and thawing snow in the mountains of the Tigris tore the banks and flooded the entire area up to the foot of the hill of Nimrud. One of the two huge lions broke while being loaded onto the rafts. Layard received a letter from Captain Felix Jones, the commander of the British steamers on the rivers, that one of the two rafts had been driven into the swamp, about a mile from the stream. It would be the middle of the summer before Captain Jones could maneuver the raft back into the fairway by reloading boxes. Fortunately nothing was lost.

During Layard's absence, digging continued around the ziggurat in Nimrud and two temples had been reached by tunneling to the east. The larger temple had two entrances, one of which was guarded by two huge human-headed winged bulls, while the other was made of large blocks of relief. On a particularly beautiful one, the king stood on one side of the second entrance together with a small stone altar. The interior of the temple was badly damaged by a fire, but there were panels with long inscriptions (today we know that it was dedicated to the god Ninurta ). The smaller temple was guarded by a pair of large naturalistic lions and contained a wonderful statue of King Assurnarsipal II , who had built the Northwest Palace.

In Nimrud, in the southern part of the Northwest Palace, they found many cauldrons with bronze vessels and bells in them. In one corner was a heap of plates, bowls, bowls and vessels, some with ornaments and particularly beautifully shaped handles. There were also weapons, such as shields and daggers, heads of spears and arrows. However, they were almost crumbled and it was possible to send only two shields to England. They found a glass and alabaster vase with Sargon's name on it, and two cubes each with a scarab inlaid in gold .

Elsewhere they found the royal throne. It was almost completely crumbled. However, Layard could make out the similarity with the throne of Sennacherib on the Lachish reliefs and that of Khorsabad . It was made of wood, only the feet seemed to be made of ivory. The wood was covered with particularly beautiful bronze work. He sent numerous fragments of these decorations to England. Through this almost accidental discovery of the room, Layard realized that there could still be many treasures hidden in Nimrud.

They worked until the summer of 1850. When the heat became unbearable and temperatures often reached 50 ° C, his draftsman Cooper and Dr. Sandwith so exhausted that Layard sent her to the mountains to relax. He and Hormuzd Rassam had repeatedly suffered from malaria attacks. So they prepared the first shipment from Kujundschik and Layard stopped work in the ruins in July. He and Rassam went to see Cooper and the Doctor, and they all traveled together to Lake Van . Unfortunately, Cooper and Doctor Sandwith's condition worsened and they both had to travel to Constantinople and then back to England. Lake Van in what is now Turkey was part of Armenia at that time . Layard made copies of the numerous inscriptions he found in the Citadel of Van and elsewhere. He sent them to the British Museum. Archibald Henry Sayce published a sensational article in the "Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society" in 1882, in which he comprehensively treated and deciphered the ancient Armenian inscriptions of Van.

Nebi Jenus (also Nabi Yunis / Nebi Yunis)

Nebi Jenus: This name means prophet Jonah in Arabic , so it refers to the story of the biblical messenger of God also handed down in the Koran . It is said that Jonas' tomb is located here, and a mosque was built in his honor. It is a place of pilgrimage. According to the Bible, the prophet was commissioned by God to predict the imminent demise of Nineveh (around 770 BC), should the inhabitants not repent of their wickedness ( Jonah 1,2 EU ).

Nabi Yunis is practically divided in two by a gorge. On the west side stood the village with the tomb of the Prophet and on the east side there was a large cemetery. Layard writes "to disturb a grave in Nebi Yunis would provoke an uproar that could lead to unpleasant consequences". However, by a trick he managed to find the contents of part of the hill. He heard that the owner of the largest house on the hill wanted to create underground spaces for himself and his family. Layard suggested that his overseer dig them up for him, provided that sculptures, stones, etc. should belong to him. The local man agreed, and Layard's overseer found the remains of a wall, some inscriptions and stones showing the name and title and the ancestral table of Esarhaddon (681–668 BC) in the summer of 1850 .

The journey to Babylonia

At the onset of winter, he laid off most of his workers. Toma Shisman remained a guard in Kujundzhik. On October 18, 1850, Layard set out with Hormuzd Rassam towards Mesopotamia, accompanied by 30 Arabs who had worked in Nimrud. He intended to visit the ruins in southern Mesopotamia.

On October 26, 1850, Layard presented himself to Captain Kemball at the British Consulate in Baghdad. Major Rawlinson (now Sir Henry) was in England. Layard stayed there until December 5th, because he was again sick with fever attacks.

They received letters of recommendation from the Turkish pasha to the chiefs of the areas to be passed and set off for Hillah . There he visited the Turkish officers of the fort, who kindly supported Layard during his stay. Since the pasha was on the move against rebellious tribes, Layard only had a visit to the famous ruins of Birs Nimrud due to the rebellious mood . Borsippa (Babylonian Barsip, also Bursip, in Strabo Borsippa, in Ptolemy Barsita), was the sister city of Babylon, on the right, western side of the Euphrates. The city god was Nebo, whose main temple had a temple tower (ziggurat). This tower, whose ruin is called Birs Nimrud, is still the most imposing in Babylonia.

Sir Robert Ker Porter had already visited Babylon in 1818. He painted the ruins there and also those of Borsippa and thought, like many others, that it was the Tower of Babel. In 1822 he published his very popular book with many illustrations: "Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, Ancient Babylonia".

In Babel , about five miles from Hillah, he had some trenches opened. They found wooden coffins with skeletons - but the stench was so strong that they had to give up further research. Elsewhere they found some stones with the inscription of Nebuchadnezzar . They opened trenches again and hit a wall, but could not make out whether it was a building. They continued to dig, but found nothing significant in the rubble. On the west side, the stones testified to solid masonry, again with the signature, but Layard did not want to speculate whether a palace of Nebuchadnezzar had once stood here. They found a fragment of a relief that showed three deities, similar to the one in Nineveh - as well as some bowls with Hebrew inscriptions. The results of his digs were a disappointment as he had hoped for more. The locals, who had occasionally found glazed stones, assured him that they had not seen any walls or slabs. The giant lion that Claudius James Rich described in 1811 in “Narrative of a Journey to the Site of Babylon” was still there, half-buried under the rubble. Layard also dug some trenches on the great hill of Amram (or Jumjuma), which Rich had also described, but again they found nothing of importance. In Hillah he bought some engraved cylinders and brooches which, after heavy rains, were washed to the surface of the ruins and then put up for sale.

Layard now visited the huge ruined hill of El Hymer eight miles northeast of Hillah , which consists of a series of terraces and platforms, similar to those in Birs-Nimrud, on which presumably sacred buildings stood.

Now he wanted to penetrate into southern Mesopotamia, to Niffer (also Nippur ) about 80 miles south of Hillah and was looking for the company of a knowledgeable sheikh. Layard and his troops left on January 15th. The Arabs from the Afaji tribe brought them into the marshland through small waterways in wooden boats called tiradas. Since no Arabs wanted to spend a night in Niffer, (today's Nuffar ), because evil spirits lived there, Layard was forced to stay with his people in the sheikh's camp. In addition, the sheikh believed that Layard was looking for gold and imagined terrible dangers. To do the sheikh a favor, he hired boats and a few additional workers to take them to the ruins every day. It was in the middle of the rainy season and pretty cold in Layard's tent.

Layard describes: “Niffer consists of a collection of hills of different heights and shapes rather than a platform like those of the ruins in Assyria. Some are separated by deep ravines. There is a tall cone in the north-east corner, probably the remains of a square tower built entirely from air-dried bricks. He is called "Bint-el-Ameer" by the Arabs, "the daughter of the prince". The Afaij said that a golden ship filled with the same precious metal was hidden inside. Masonry made of air-dried and burnt stones protruded from under the cone. The stones were smaller than those of Babylon and of a longer, narrower shape. Many had inscriptions with the name of the king of this city. "

Layard divided his workers into groups and had them dig in different parts of the ruin. They found many vases and earthenware containers, some smooth and others glazed, as well as bowls with Judean inscriptions, similar to those from Babylon. On the fourth day they came across a place with 4 to 5 coffins of different sizes, the largest about 1.80 m and the smallest a children's coffin of about 0.90 m.