Kelek (raft type)

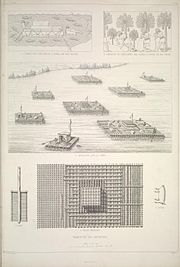

Kelek , also Kellek ( Arabic ), pl . aklāt or kelekāt, was a raft that had been on the Euphrates and Tigris in Iraq , Syria and eastern Turkey since the 3rd millennium BC. Was used to transport loads until the 20th century. Under a lattice-shaped wooden platform, inflated hoses made of animal skins provided buoyancy.

history

Rafts made of animal skins have been known in Mesopotamia under the Akkadian name kalakku since at least the second half of the 3rd millennium, the time of King Sargon of Akkad . There are images on Assyrian reliefs. On cuneiform tablets from the beginning of the 1st millennium they were described as "raft on tubes" or "ship made of coarse leather". The Arabic word kelek is derived from kalakku and is occasionally found in place names where it means “ferry”.

Other rafts consisted of reeds (Akkadian amû ), referred to as “ reed floating in the water”, and the probably larger wooden rafts ḫallimu (Pl. Ḫallimānū ), with which trees, cattle and soldiers were transported.

The transport of goods on the Euphrates and Tigris as well as on the widely branched tributaries of the Shatt al-Arab took place mainly on a regional basis. In addition, goods from northern Mesopotamia ( Jazīra ) and Asia Minor also entered the country on the two rivers. In the 5th century BC The ancient Greek historian Herodotus reported about basket boats that were covered with skins and filled with straw on the inside. The description of the boat shape referred to the circular basket boats called guffa , but Herodotus seems to have meant Kalakkus with the described cargo and transport route . The cargo consisted of clay jugs with wine and a donkey. The control downstream was carried out by two men with stakes. The stated payload for the largest boats of up to 5000 talents (a Solonic talent corresponds to 26 kilograms) is probably exaggerated. The boats were made in Armenia and, after they had arrived with their cargo in Babylonia, were dismantled into individual parts. There the wooden parts were sold and the skins were transported back overland on the donkeys they had brought with them.

Old Babylonian itineraries describe how the route of the donkey caravans went on the way back . At the time, they were not intended as a travel guide, but rather as an accounting tool to document a business trip. The main route began in Larsa in southern Mesopotamia, led along the Euphrates via Babylon to Sippar, 60 kilometers to the north . From there the caravan took the way to the Tigris and up to Aššur in its vicinity . There you left the river behind you and on the way west you crossed an area in which there were enough watering holes on the way, and you got to Schubat-Enlin, the residence of Šamši-Adad I (18th century BC). on the upper reaches of the Chabur (today Tell Leilan ). Crossing the river, the path continued west to the upper reaches of the Belich and followed this downstream to its confluence with the Euphrates at Tuttul . The final stop was Emar a little above on the Euphrates. It is unclear why this detour was accepted. The direct route on the Euphrates via Mari may not have been safe from raids.

Cuneiform tablets from the time of Prince Gudea (21st century BC) describe the construction of a temple and the origin of the materials used in its capital Lagaš in southern Mesopotamia. Lagaš obtained goods through its port city of Gu'aba on the Persian Gulf , from the area around Kirkuk and from areas on the central Euphrates and northern Syria. Basalt came on rafts from the Basalla Mountains near Zalabiya on the Euphrates. Tidanum as a reference point for alabaster may also have been there. Cedar wood was obtained from the Amanus Mountains ( Amanos Dağları ) . Other types of wood came from Urschu ( Şanlıurfa ).

There were more rafts on the Tigris than on the Euphrates, because especially on the lower reaches of the Euphrates in Iraq there was a risk that the sensitive skins could be damaged by rocks. The smaller basket boats (Pl. Guffāt ) were used here. Another problem on the Euphrates was the constantly changing position of the sandbanks, which emerged when the water was low in the summer months through to winter. The rivers had their highest water level in spring, when the snowmelt in the mountains, and into summer.

Assyrian reliefs show, in addition to the large rafts, tiny platforms supported by one or two goat skins that were used by a person to cross the river. The Behistun inscription , in which the Achaemenid king Dareios I (549-486) is reported, shows that this practice in Mesopotamia was also known in Persia . In the Persian national epic Shāhnāme , which was written between 977 and 1010, horses are brought across a river with the help of inflated goat skins tied to the sides.

16th century travelers reported Armenian boatmen on rafts. The starting point for the trip on the Tigris was Diyarbakır . Often it was Kurds and Christians from Northern Iraq who arrived in Baghdad almost every day at the beginning of the 20th century, heavily laden with logs and grain, and who started their journey home by land with donkeys. During the First World War , military goods were transported on the Tigris downstream from Mosul to Baghdad. Keleks covered this distance in three to four days when the water level was sufficient. Upstream trekking was common on short trips .

Construction

Keleks consisted of a framework of wooden poles tied together and attached to rows of 50 to 400 inflated sheep or goat skins. The Armenians called the swimming hoses burdjuk. In the case of smaller keleks, the frame was made of willow rods or some other flexible material. For the transport of people the ground was covered with a thick layer of reed grass, occasionally one or two huts made of the same material were added. In the largest modern keleks, up to 600 hoses made of animal skins were tied together, each with a load-bearing capacity of around 25 kilograms. The vehicle was steered by two rowers.

Keleks in literature

- In a fairy tale cycle written in the New Aramaic language, some inhabitants of a village in the story The Wood Chopper and the Forty Thin Beards try in vain to flee from the villain on a Kelek down the Euphrates to Baghdad.

- In the volume Oranges and Dates by Karl May , the Mesopotamian heroes cross the river in a Kelek and in the chapter On the Tigris of the volume In the Kingdom of the Silver Lion I , Kara Ben Nemsi and Hajji Halef Omar travel to Baghdad on a Kelek.

literature

- Horst Klengel : Trade and traders in the ancient Orient. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1979, ISBN 3-205-00533-3 , p. 95 f.

- Hans Kindermann: Kelek. In: Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition . Volume 4, 1978, p. 870

Web links

- Thea Naab: Three years in Mesopotamia. Commission-Verlag der Basler Missionsbuchhandlung 1918 Describes the journey on a Kelek from Diyarbakir to Mosul

Individual evidence

- ↑ A. Salonen: Raft. In: Erich Ebeling , Bruno Meissner , Dietz-Otto Edzard (eds.): Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Aräologie . De Gruyter, Berlin 1999, vol. 3, p. 88

- ↑ a b Klengel, p. 95

- ↑ Klengel, pp. 96, 99

- ↑ Klengel, p. 71

- ↑ a b Brill, p. 114

- ↑ Brill, p. 115

- ↑ Carl Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt Armenia then and now. Travel and research. Volume 1: From the Caucasus to Tigris and to Tigranokerta. B. Behrs Verlag, Berlin 1910, p. 340

- ↑ Heinz Lidzbarski (Ed.): B. 6. The wood cutter and the forty thin beards. In: Stories and Songs from the New Aramaic Manuscripts. Emil Felber publisher, Weimar 1896, online at Zeno.org

- ↑ Karl May: Chapter: Christ's blood and justice. In: oranges and dates. Travel fruits from the Oriente by Karl May. Volume X, Freiburg i.Br. 1910, online at Zeno.org

- ↑ Karl May: Chapter: On the Tigris . In: In the realm of the silver lion. Volume I / II, p. 366