Shahnama

Shahnameh (also Shahnameh ; persian شاهنامه Šāhnāme , DMG Šāhnāma , rulers book '), in German known as King book or Book of Kings , referred in particular the life's work of the Persian poet Abu'l-Qāsim Firdausi (940-1020) and at the same time the national epic of the Persian-speaking world ; According to the poet, it took him 35 years to write it down. It is one of the most famous works of Persian and world literature . With almost 60,000 verses in the form of distiches , it is more than twice as long as Homer'sEpics and more than six times as long as the Nibelungenlied .

In addition to many orally transmitted stories (especially - as Firdausi himself states - from the circle of the Dehqans ), the author also had written templates. An important source seems to be a translation of the late Sassanid -built Mr. Buchs ( Xwaday-NAMAG ) to have been.

In addition, other Schahnamehs (books of kings) or similarly named works that were written in honor of or on behalf of rulers ( shahs ) are known.

The historical core

The heroic epic deals with the history of Persia before the Islamic conquest in the seventh century. It begins with the creation of the world and describes the mythical development of the Persian civilization (use of fire, development of culinary art, blacksmithing and the emergence of a codified legal system, the foundation of traditional festivals, etc.). The work leads the reader, although not exactly chronologically, from the past to the fall of the Sassanids , the last pre-Islamic ruling dynasty, with references to the present of Firdausī. Some of the literary figures live for several hundred years, but most only live one generation. The later the events described, the stronger the reference to real events and people, so that the epic also contains a lot of real historical information, especially for the late Assanid period, and is a very important source.

In his work Firdausī does not use the unfamiliar Greek word “Persia” as a geographical term for the empire, which the Greeks derived from the name of the province of Fārs (Greek Persis ), but instead the native name Irān, which has been used since the Sassanids ( Persian ايران, DMG Īrān ), which covered a much larger area than the current state of Iran . The shahs and heroes come and go, and the only thing that remains is - as Firdausī explains - only Iran . Sunrise and sunset, none of which are alike, describe the passage of time.

History of origin

The genesis of the Shahnameh Firdausi is complex; this applies above all to the sources and templates that were used. Already at the time of the Sassanids a work was apparently created, the content of which was later received and which is referred to in research as the men's book (Xwaday-namag) . It was apparently an official Iranian "national story".

It is known that at the instigation of Abū Manṣur Moḥammad ibn ʿAbdor-Razzāq, the governor of Tūs at the time, a “Book of Kings” was made. This work was based on reports by Zoroastrian priests, which had been passed on from generation to generation in oral traditions and thus preserved Sassanid-Central Persian traditions.

The first to put the pre-Islamic history of Persia into poetry after the fall of the Sassanid Empire (651) was Abū Mansūr Muhammad ibn Ahmad Daqīqī . He was a poet at the court of the Samanids (who were very interested in the Persian cultural heritage) and supposedly a follower of the Zoroastrian religion, which was life-threatening in those days. His Turkish servant is said to have stabbed him. Before his violent end he had written a thousand verses with the so-called Shāhnāme-ye Mansur , the beginning of his work being the description of the reign of Goštāsp and the appearance of Zarathustra . One verse of his poetry reads:

"Daqīqī, that which was born into this world

of good and bad, chose four things,

ruby red lips and the sound of the harp,

blood-red wine and Zarathustra's song."

Firdausī reports that Daqīqī appeared to him in a dream and asked him to continue his work. Firdausī has included some of Daqīqī's verses in his work. He began writing in 977 and finished his work around 1010. Firdausī wrote his mighty epic at a time when the new Ghasnavid dynasty was turning to an Islamic state idea and pre-Islamic things were not in demand. Firdausī was more careful in his poetry than Daqīqī and avoided appearing pro-Zoroastrian. Some authors therefore claim that several verses of Daqīqī, which would have been too controversial with the ruling class, were not adopted by Firdausī. Nevertheless, the work contains clear references to the Zoroastrian traditions of Iran, which are still alive today in the celebration of the Iranian New Year festival " Nouruz ".

In order to escape hostility, Firdausī dedicated his work to the Ghasnavid Sultan Mahmud .

content

The shāhnāme is divided into 62 sagas, consisting of 990 chapters with almost 60,000 verses. Firdausī himself speaks of 60,000 verses. The present publications contain 50 sagas with a little more than 50,000 verses.

In addition to the kings depicted in the respective sagas, the main character is the mythical hero Rostam , Prince of Zabulistan , who defends the borders of ancient Iran against his enemies, especially the Turans , in many battles .

The Shahnameh is not only a monument to Persian poetry, but also a piece of historical narration, since Firdausī in his work reproduces what he and his contemporaries considered the history of Iran. When describing historical events, Firdausī incorporates advice directed at his fellow human beings. He apparently used written and oral sources, but it is not a question of historiography in the true sense of the word: historical events are often linked to fabulous narratives, so that actually documented people and events mix with fictional descriptions.

The epic begins with the reign of the primeval kings, in which the rapid development of human civilization is depicted. The epic really comes to life with legend 4 of Jamschid and his arguments with Zahak , who was overthrown by the blacksmith Kaveh and Fereydūn . The division of the old Iranian empire among the three sons of Fereydūn leads to the first fratricide. Iradsch is murdered by his brothers Tur and Salm. This is the beginning of the enmity between Iran and Turan . First Manutschehr avenged the death of his father Iradsch.

Sām is reported under Manutscher's reign . The adventurous youth stories of Sām's son Zāl , his love for Rudabeh and the birth and first adventures of Rostam also fall during this period . The murder of the captive King Nowzar , the successor of Manutscher, by the Turanian King Afrasiab rekindles the war with Turan. The war, although interrupted several times for a long time, was to last the time of the reign of the five following kings. Rostam can already grab Afrasiab by the belt in the first battle, but the belt breaks and the enemy king escapes. During the reign of Kai Kawus , who was incomprehensible to his father Kai Kobad , who was popular as ruler , the greatest heroic deeds of his servant Rostam and also the tragic clash with his son Sohrāb , who is killed by his own father out of ignorance of his true identity. Afrasiab kills Siyawasch , who fled to him because of disagreements with his father Kai Kawus and to whom he gave his daughter for marriage. This murder makes the war irreconcilable.

In the further course of the war, which is under the motto "Vengeance for Siyawasch", Rostam takes a back seat. Kai Chosrau , the son of Siyawasch, who had been fetched from Turan with great difficulty, ended the war victoriously. Afrasiab escapes, but is discovered and killed. Before that, the love story between Bijan and Manischeh , the daughter of Afrasiab, is told. In Lohrāsp , with whom a branch line comes to the throne, we hear almost only of the adventures of his son Goshtasp . Under Goschtasp preach Zarathustra his new religion. As a result, war breaks out again. The pioneer of the religion of Zarathustra is Esfandiyar , the son of King Goshtasp. Esfandiyar is repeatedly sent to war by his father, who promised him the throne. Finally he should take Rostam prisoner. Esfandiyar, who has taken a bath of invulnerability with his eyes closed, is killed by Rostam with an arrow shot in the open eyes. However, Rostam also falls a little later. With Darab and Dara the epic leads on to Alexander .

With Ardashir I. The report history begins Sassanian until the fall of the Persian Empire with the battle of Kadesia . The epic ends with the description of the fate of the last king of the Sassanids, Yazdegerd III.

For the Rostam legend, the first fifteen kings are of interest, which the Avesta names and whose order there corresponds to the order in Shāhnāme. This arrangement was probably made under Shapur I to prove the legitimacy of the dynastic claims of the Sassanids .

The kings or rulers

According to the Iranist Zabihollāh Safā , the content can be divided into three periods:

- daure-ye asāṭīrī ( Persian دورهٔ اساطيرى) - mythical epoch

- daure-ye pahlawānī ( Persian دورهٔ پهلوانى) - heroic epoch

- daure-ye tārīḫī ( Persian دورهٔ تاريخى) - historical epoch

Kings of the Mythical Age

- Sage 1 = Gayōmarth , the first human king in Persian mythology.

- also includes the saga of Siyāmak , son of Gayōmarth and first king of the Pishdād dynasty .

- Sage 2 = Hōšang , the grandson of Gayōmarth, who brings people right and justice.

- Sage 3 = Tahmōrath , the tamer of the evil spirits, who among other things introduces the writing.

- Sage 4 = Ğamšīd (Jamschid) , son of Tahmōrath, founder of the New Year festival Nouruz .

- Say 5 = Ẓahhāk , the demon king who makes a pact with Ahrimān .

- Sage 6 = Fereydūn , who kills Ẓahhāk and before his death divides the known world among his three sons.

- contains the legend of the three sons: Iradsch receives Iran from his father and is murdered out of envy by his two brothers Selm and Tūr.

Kings of the heroic age

- Sage 7 = Manutschehr , who avenges the death of his father Iradsch and replaces Fereydūn on the throne.

- Say 8 = Nauẕar

- Say 9 = Ẓau

- Say 10 = Garshasp

- Saga 11 = Kay Kobād , a descendant of Fereydūn and first king of the Kayāni dynasty .

- Sage 12 = Kay Kāōs

- Legend 13 = Kay Chosrau ( Cyrus II ?)

- Say 14 = Lohrāsp

- Say 15 = Goštāsp

- Say 16 = Bahman

- Say 17 = Hōmā Tschehrāẓād

- Say 18 = Kay Dārāb

- Sage 19 = Dārā ( Darius III. )

- Sage 20 = Iskandar (Alexander the Great)

- Sage 21 = dynasty of the Ashkānīyān (Arsakids or Parthians )

- Legend 22 = beginning of the Bābakān dynasty (Sāsānids)

Kings of the historical age (dynasty of the Bābakān)

- Legend 23 = Ardashir I.

- Legend 24 = Shāpur I.

- Legend 25 = Hormaẓd I.

- Sage 26 = Bahrām I.

- Sage 27 = Bahrām II.

- Say 28 = Narsī

- Legend 29 = Hormaẓd II.

- Say 30 = Ẓulaktāf (Shāpur II.)

- Legend 31 = Ardashir II.

- Sage 32 = Shāpur III.

- Sage 33 = Bahrām IV.

- Sage 34 = Yaẓdgerd I.

- Sage 35 = Bahrām Gūr

- Sage 36 = Yaẓdgerd II.

- Legend 37 = Hormaẓd III.

- Say 38 = Peroẓ

- Say 39 = balash

- Say 40 = Ghobād

- Legend 41 = Anuschravān (Chosrau I.)

- sage 42 = Hormaẓd IV.

- Say 43 = Parveẓ

- Say 44 = Schīruy

- Say 45 = Ardaschir III.

- Say 46 = Farāyin

- Say 47 = puran wick

- Say 48 = Āẓarmi wick

- Say 49 = Farrochẓād

- Sage 50 = Yaẓdgerd III.

Reception history

The shahnameh was and is the basis of the Persian national consciousness in the Persian-speaking world - in the states of Iran , Afghanistan and Tajikistan . Many linguists believe that the reason that the modern Persian language is nearly identical to the 1,000 year old Firdausī language is due to the existence of the Shahnameh. The work of Firdausī had and still has a profound influence on the language and culture of Iran; the shāhnāme is one of the main pillars of the modern Persian language. Studying Firdausī's masterpiece is a prerequisite for mastering the standard Persian language, as demonstrated by the influence of the Shahnameh on the works of numerous Persian poets. The language-forming power of Firdausī's work is demonstrated by the fact that the text, written a thousand years ago, can still be read and understood by anyone who speaks Persian without any problems.

Impressively presented by storytellers in tea rooms, but also immortalized in a large number of manuscripts, the shāhnāme has made a decisive contribution to the cultural community of the peoples of the Middle East, Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan through its language and its subject matter. According to Jalāl Chāleghī Mutlaq, Firdausi conveys the following values and behaviors in Shāhnāme: serving God, respecting God's laws, maintaining religious steadfastness, cherishing his country, loving his family, wife and child, helping the poor and needy, striving for wisdom, working for justice , plan for the long term, strive for balance, maintain politeness, be hospitable, show chivalry, grant forgiveness, show gratitude, be happy and content with what is given, work hard, be peaceful and gentle, be faithful, love the truth and abhor untruth, Be faithful to the contract, maintain self-control, be humble, hungry for knowledge and be eloquent . With his work, Firdausī has not only attempted to document the history of Iran, but also to poetically grasp what, from his point of view, defines Iran.

Under the reign of Reza Shah and the establishment of an Iranian nation state, Firdausīs Schahname and the values he conveyed were of outstanding importance. A mausoleum was built for the poet of the Iranian national epic in 1934, in which his remains were buried. Under the reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi , a festival in honor of Firdausī, the annual Tus Festival , was founded in 1975 under the patronage of Shahbanu Farah Pahlavi , which documents the status of the reception history of the Shahnama as part of a literary symposium, among other things.

Translations

A first German translation of the Schahname by Count Adolf Friedrich von Schack appeared in 1851 under the title Heldensagen des Ferdusi . A text version in three volumes was published under the title Firdusii Liber Regum qui inscribitur Schahname Johann August Vullers in 1877 and 1878. The third volume could only appear after Vuller's death in the arrangement of S. Landauer. The first and so far only translation in verse is by Friedrich Rückert . Volume 1, which contains the legends I to XIII, did not appear until after Rückert's death in 1890. Volumes 2 and 3 were published in 1895 and 1896. Rückert limited himself in his translation to the first fifteen kings, which the Avesta already calls, and is of particular interest for the Rostam legend. Rückert had the story of Rostam and his son Sohrab as early as 1838 in a retouch under the title Rostem und Suhrab. A heroic story published in 12 books by Theodor Bläsing in Erlangen.

Interest in shāhnāme has never waned in the German-speaking world. Again and again there were prose texts that wanted to bring the story of the kings of Iran closer to German readers. To this day, Firdausī's work has lost none of its radiance. And it is still true today that anyone who wants to understand Iran must have read Firdausī.

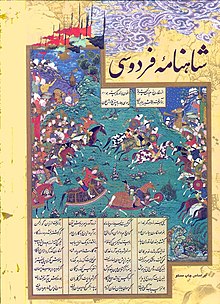

Some illustrations on the shahnameh

Battle scene between the troops of Iran and Turan under Kay Chosrau and Afrāsiyāb

Farāmarẓ, son of Rostam , mourns the death of his father and his uncle Ẓavāra

Ardaschīr meets Gulnār, Ardavān's slave and treasurer.

King Anuschravāns vizier Boẓorgmehr challenges an Indian ambassador to a game of chess after the rules have been explained to him.

Shahnama editions

The first attempt to publish an edition of Shāhnāme on the basis of the known manuscripts was made by Mathew Lumsden. The first volume of the eight-volume edition was published in Calcutta in 1811 . Lumsden had looked through 27 manuscripts for his edition. Lumsden did not get beyond the first volume, however. Turner Macan took over the editing and in 1829 published the first complete edition of the Shāhnāme under the title The Shah Namah, An Heroic Poem, carefully collated with a number of the oldest and best manuscripts ... by Abool Kasim Firdousee by Turner Macan.

Between 1838 and 1878 Julius Mohl published another edition under the title Le Livre des Rois . In addition to an extensive introduction, the seven volumes of this edition also contain a French translation. Mohl used 35 manuscripts for his edition, but neglected to cite the respective source for the individual text passages.

The German orientalist Johann August Vullers created a new edition in three volumes based on the Macan and Mohl editions, which was published between 1877 and 1884 under the title Firdusii liber regum . Its edition extends to the end of the Kayanids and goes into detail on the textual differences between the editions of Mohl and Macan.

In the years 1934 to 1936 M. Minovi, A. Eqbal, S. Haim and S. Nafisi then prepared a ten-volume illustrated edition for Ferdausi's millennium based on the edition of Vullers, with the parts from the editions by Turner and Mohl being supplemented which Vullers had not worked on because of his advanced age. This first edition produced and frequently reprinted in Tehran has long been considered the best edition available.

The so-called Moscow edition by EE Bertel, which is mainly based on the manuscript from 1276 kept in the British Museum and the Leningrad manuscript from 1333, is considered to be the first critical Shāhnāme edition. The edition was published by the Institute for Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in nine volumes from 1960 to 1971.

In 1972, the Iranian Ministry of Arts and Culture established the Schahname Foundation (Bonyād-e Shahname-ye Ferdowsi), which was headed by Mojtabā Minovi. The aim of the foundation was a complete collection of the copies of all manuscripts and the publication of a new, comprehensive Schahname edition. However, the foundation was only able to publish three volumes (Dāstān-e Rostam o Sohrāb, 1973; Dāstān-e Forud, 1975; Dāstān-e Siāvush, 1984) .

A comprehensive critical edition was written from 1988 by Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh, who took into account all known manuscripts, whereby in addition to the already known manuscripts the Florence manuscript from 1217 found in 1977 is of particular importance. Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh finished the 2009 edition. It comprises a total of eight volumes and four commentary volumes. This edition surpasses the Moscow edition by far, as it contains numerous text variants and extensive commentary. Based on the series of Persian texts of the Bongah-e Tarjama va Nashr-e Ketab, which appeared in Tehran from 1959 to 1977, this Shāhnāme edition appears as number 1 in the Persian Text Series edited by Ehsan Yarshater .

The editors of Schahname are faced with the problem that the oldest known manuscript, the Florence manuscript, dates from 1217, two hundred years after Ferdausi's death. If you compare the individual manuscripts, you will notice numerous text variations consisting of additions, deletions or changes. Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh initially collected forty-five manuscripts in copies for his edition, from which he then selected fifteen as a text basis.

See also

- Iranian Studies

- Iranian mythology

- Persian literature

- Persian coffee house painting

- Tus Festival

- Rostam and Sohrab

Media and public reception

Film adaptations

- 1972: Rustam i Suchrab (German: The battle in the valley of the white tulips )

Exhibitions

- 2010/2011: Epic of the Persian Kings. The Art of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh , Fitzwilliam Museum , Cambridge

- 2011: Schahname exhibition in the Berlin Museum for Islamic Art ( Pergamon Museum )

expenditure

- Johann August Vullers: Firdusii liber regum . 3 vols. Leiden 1876–84.

- M. Minovi, A. Eqbal, S. Haim, Said Nafisi: Schahname-je-Ferdousi . IX. Tehran 1933-35.

- EE Bertels, Abdolhosein Nuschina, A.Azera: Firdousi, Šach-name. Kriticeskij tekst pod redakcii . I-IX. Moscow 1960–1971.

- Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh (Ed.): The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) (Vol. 1-8). Published by the Persian Heritage Foundation in association with Bibliotheca Persica. New York 1988-2008, ISBN 978-1-934283-01-1 .

- Martin Bernard Dickson and Stuart Cary Welch: The Houghton Shahnameh. 2 volumes, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (USA) 1981

Shahnameh translations

German

-

Friedrich Rückert (translator): Firdosi's book of king (Schahname). Edited from the estate by Edmund Alfred Bayer, 3 volumes, published by Georg Reimer, Berlin 1890–1895 (Copyright: Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin); numerous reprints, including: Imperial Organization for Social Services, Teheran 1976 (in the series The Pahlavi Commemorative Reprint Series , edited by M. Moghdam and Mostafa Ansari).

- Friedrich Rückert: Firdosi's Book of Kings (Schahname) Sage I-XIII. Edited from the estate by EA Bayer. Berlin 1890; Reprint: epubli, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86931-356-6 .

- Friedrich Rückert: Firdosi's Book of Kings (Schahname) Sage XV-XIX. Edited from the estate by EA Bayer. Berlin 1894; Reprint: epubli, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86931-407-5 .

- Friedrich Rückert: Firdosi's Book of Kings (Schahname) Sage XX-XXVI. In addition to an appendix: Rostem and Suhrab in Nibelungen size. Alexander and the philosopher. Edited from the estate by EA Bayer. Berlin 1895; Reprint of the first edition, epubli, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86931-555-3 .

- Friedrich Rückert: Schahname - The Book of Kings, Volume 1. New edition. Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-7450-0757-2 .

- Friedrich Rückert: Schahname - The Book of Kings, Volume 2. New edition. Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-74675-120-7 .

- Friedrich Rückert: Schahname - The Book of Kings, Volume 3. New edition. Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-74858-270-0 .

- Helmhart Kanus-Credé: The Book of Kings. Augustin, Glückstadt

- Book 1/6. 2002, ISBN 3-87030-127-9

- Book 7. 2003, ISBN 3-87030-128-7

- Book 8/9. 2003, ISBN 3-87030-130-9

- Joseph Görres : The Book of Heroes of Iran. From the Shah Nameh des Firdussi. I-II, Georg Reimer, Berlin 1820

- Werner Heiduczek (with the assistance of Dorothea Heiduczek): The most beautiful legends from Firdausi's book of kings, retold. (After Görres, Rückert and Schack. Technical advice and epilogue: Burchard Brentjes) The children's book publisher, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-7684-5525-4 .

- Adolf Friedrich von Schack : Hero sagas of Firdusi. In a German replica with an introduction by Adolf Friedrich von Schack. In three volumes, Cotta, Stuttgart 18xx.

- Uta von Witzleben : Firdausi: Stories from the Schahnameh. Eugen Diederichs Verlag. Düsseldorf and Cologne 1960 (new edition 1984, ISBN 3-424-00790-0 ).

- Abū'l-Qāsem Ferdausi: Rostam - The legends from the Šāhnāme. Translated from Persian and edited by Jürgen Ehlers. Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-050039-7 ; New edition: Schahname - The Rostam Legends , 2010

- Abu'l-Qasem Firdausi: Shahname - The Book of Kings. Translated from Persian into verse by Robert Adam Pollak (†), edited and edited by Nosratollah Rastegar. With an introduction by Florian Schwarz. Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-87997-461-0 ; 4 hardcover volumes in a slipcase, approx. 1360 pages, books XX-L.

English

- Arthur Warner, Edmond Werner: The Shahnama . 9 vol. London 1905-1925.

- Dick Davis: Shahnameh. Penguin Group, New York 2006, ISBN 0-670-03485-1 .

French

- Jules Mohl : Le Livre des Rois I-VII. Paris 1838–1855.

literature

- Fateme Hamidifard-Graber: From bindweed to cypress - the plant kingdom in Ferdousī's "Book of Kings" . Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-87997-368-2

- Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila: Khwadāynāmag. The Middle Persian Book of Kings. Brill, Leiden / Boston 2018.

- Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh: Notes on the Shahnameh. Vol 1-4 . Published by the Persian Heritage Foundation. Eisenbraun, Winona Lake / Indiana 2001-2009, ISBN 0-933273-59-2 .

- Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh: The women in the Shahname - their history and position while taking into account pre- and post-Islamic sources . Cologne 1971.

- Theodor Nöldeke : The Iranian National Epic . 2nd edition Berlin 1920 ( digitized version of the University and State Library of Saxony-Anhalt, Halle).

- Parvaneh Pourshariati: The Parthians and the Production of Canonical Shahnames. In: Henning Börm, Josef Wiesehöfer (eds.): Commutatio et Contentio. Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East. In memory of Zeev Rubin (= series history. Vol. 3). Wellem, Düsseldorf 2010, ISBN 978-3-941820-03-6 , pp. 346-392.

- Stuart Cary Welch: Persian illumination from five royal manuscripts of the sixteenth century. Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1976, 2nd edition 1978, pp. 29 and 34–53

- Fritz Wolff : Glossary on Firdosis Schahname . Reprint of the first edition from 1935. Hildesheim 1965 and Teheran 1377/1998.

Web links

- English translation of the "Book of Kings"

- Shahnama Project Uni. Cambridge (English)

- The Princeton Shahnama Project (English)

- Heinrich Heine's poem about the life of Firdausī

- Khosro Naghed : Firdowsi and the Germans (Persian)

- Example of a Shahname reading (Persian)

- 1000 Years of Schahname - Exhibition in Cambridge

- Schahname exhibition (2011) in the Berlin Museum for Islamic Art ( Pergamon Museum )

- Discussion on the Berlin Schahname exhibition in zenith

- Book of Kings BSB (Cod.pers. 10)

Individual evidence

- ^ Paul Horn: History of Persian Literature. CF Amelang, Leipzig 1901 (= The literature of the East in individual representations, VI.1), p. 112 f.

- ↑ The name reproduction of the title varies. For this work see especially Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila: Khwadāynāmag. The Middle Persian Book of Kings. Leiden / Boston 2018.

- ^ Theodor Nöldeke: The Iranian national epic . 2nd edition Berlin 1920; see. also The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity . Vol. 2 (2018), p. 1599.

- ^ Theodor Nöldeke: The Iranian national epic . 2nd edition Berlin 1920, p. 16.

- ↑ See Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila: Khwadāynāmag. The Middle Persian Book of Kings. Leiden / Boston 2018, pp. 139ff.

- ↑ Abu'l-Qasem Ferdausi: Rostam - The legends from the Sahname . Translated from Persian and edited by Jürgen Ehlers. Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-050039-7 , p. 383.

- ↑ a b Ferdowsis Shahnameh . Zoroastrian Heritage (English)

- ↑ Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh: FERDOWSI, ABU'L-QĀSEM i. Life . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , accessed on May 15, 2013 (English, including references)

- ^ Theodor Nöldeke: The Iranian National Epic . 2nd edition Berlin 1920, p. 44f.

- ↑ Abū'l-Qāsem Ferdausi: Rostam - The legends from the Šāhnāme . Translated from Persian and edited by Jürgen Ehlers. Stuttgart 2002, p. 405.

- ↑ Volkmar Enderlein , Werner Sundermann : Schāhnāme. The Persian Book of Kings. Miniatures and texts of the Berlin manuscript from 1605. Translated from the Persian by Werner Sundermann, Gustav Kiepenheuer Verlag, Leipzig / Weimar 1988, ISBN 3-378-00254-9 ; Reprint ISBN 3-7833-8815-5 , blurb .

- ↑ Jalal Khaleqi Mutlaq: Iran Garai dar Shahnameh (Iran-centrism in Shahnameh). In: Hasti Magazine , Vol. 4. Bahman Publishers, Tehran 1993.

- ^ Ehsan Yarshater: Introduction . In: Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh (Ed.): The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings ) (Vol. 1). Published by the Persian Heritage Foundation in association with Bibliotheca Persica. New York 1988, ISBN 0-88706-770-0 , p. Vi.

- ^ Ehsan Yarshater: Introduction . In: Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh (Ed.): The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings ) (Vol. 1). Published by the Persian Heritage Foundation in association with Bibliotheca Persica. New York 1988, ISBN 0-88706-770-0 , pp. Vii.

- ^ J. Khaleghi-Motlagh: Mo'arrefi o arzyabi-e barkhi az dastnevisha-ye Shahname . Iran Nameh, III, 3, 1364/1985, pp. 378-406, IV / 1, 1364/1985, pp. 16-47, IV / 2, 1364/1985, pp. 225-255.

- ↑ Shahnameh. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed March 2, 2017 .

- ↑ A thousand years of love . In: FAZ , December 9, 2010, p. 32

- ↑ Archive URL: Schahname Archived copy ( Memento from March 20, 2016 in the Internet Archive ).