Yazdegerd III.

Yazdegerd III. (also Yazdgird , Persian یزدگرد Yazdgerd , 'created by God' [ jæzdˈgʲerd ]; † 651 ) from the house of the Sassanids was the last great king of Persia from 632 (633?) To 651.

Life

The Sassanid Empire in Yazdegerd's time

According to Tabari , Yazdegerd was 28 years old at the time of his death and will therefore have been born around the year 623. He was a grandson of Chosraus II , after whose death in 628 a chaotic time had dawned in the Sassanid Persian Empire, during which a whole series of briefly ruling kings and queens came to power. The empire was exhausted both from the internal fighting and from the bloody war against the East , which had only ended in 629 . When the young Yazdegerd finally succeeded in asserting himself as the last male member of the royal family, the time of turmoil seemed to be over, and hopes were raised that the exhausted empire would rise again. He was enthroned in Istachr , which was a symbolic place of the Sassanid dynasty, although the Ctesiphon was not in his hand at that time either. In fact, the loss of reputation of the kingship proved to be irreparable in the subsequent period.

Invasion of the Arabs

Soon after, however, the Muslim Arabs broke into both the Eastern Roman and Sassanid empires (see Islamic Expansion ). The emissaries of the first caliph called on the Sassanids to submit or to accept the new religion, which the young Persian king refused. The Persian troops were actually able to repel an initial attack in the so-called Battle of Bridge 634 and initially drive the Arabs out of Mesopotamia; but since there was again internal turmoil afterwards, the Sassanids could not take advantage of the victory. In 638 (more likely than 636 or 637) the battle of Kadesia in what is now Iraq took place : The Persian general Rostam Farrochzād , who had still won in 634, fell this time after a hard fight and his army was crushed by the Arabs. With the defeat, there was initially no Sassanid army in the way of the victors, which is why they conquered Mesopotamia with the main residence Ctesiphon and captured the Persian state treasure with almost no effort . The Persian Northwest Army , which was stationed in Persarmenia and Azerbaijan, did not intervene in the fighting - it is believed that their noble commander had reached a treason with the Arabs. With the defeat of the Romans in the Battle of Jarmuk in 636, Syria was also open to the attackers; Since an Eastern Roman counterattack was not to be expected for the time being, they were able to concentrate largely on the war against Persia. After some discussion, the Muslims decided not to be satisfied with conquering Mesopotamia, but to advance further into the Iranian plateau.

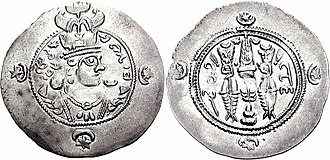

Yazdegerd meanwhile had to flee from his capital, Ctesiphon , and withdrew to Iran proper , where he organized the resistance and gathered troops. (The alleged correspondence between him and the caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb is almost certainly a later forgery due to numerous anachronisms .) However, (as can be proven by coinage) it was no longer recognized unchallenged throughout the empire and could only ever gain regional authority procure.

In 642, however, his army again succumbed to the attackers in the bloody battle of Nehawend (or Nihawand, south of today's Hamadan ), which decided the fate of Yazdegerd and his dynasty. Because now the greats of his empire finally lost confidence in the victoriousness of the young king. Sometimes they turned away and often tried to make arrangements with the conquerors; meanwhile, in other parts of the empire the Persians continued to offer the Arabs some fierce resistance.

Escape and death

Yazdegerd fled further and further east, always looking for support, ultimately in vain. He also sent several appeals for help to the Chinese Empire of the T'ang , but due to the distance they could not or would not provide effective support. 651 became Yazdegerd III. killed at Merw , probably on behalf of the governor there, who was tired of the king and wanted to rule himself. The Perso-Arab authors still report centuries later that the descendants of the governor or the miller who killed Yazdegerd on his behalf were called "regicide" - according to Persian belief, the person of the great king was holy and sacrosanct , the murder of Yazdegerd so it was a grave sacrilege.

Yazdegerd's son Peroz was able to flee to the Turks and finally to the court of the T'ang emperors , but a return to the throne was out of the question; Peroz ended his life in exile in China. Peroz 'younger brother Bahram had probably also fled to the Chinese court. The Persians who fled there also seem to have been several Christians, who thus acted as mediators of Christianity in China.

With Yazdegerd III. thus also ended the rule of the Persian dynasty of the Sassanids. His death marks the end of antiquity and the ancient Orient and the beginning of the Middle Ages for the Near East . Yazdegerd was also the last Persian ruler to follow Zoroastrianism . Many devout Zoroastrians therefore count the years to this day since the year 632/633, the king's accession to the throne.

But the memory of the last Sassanids remained important for some Muslims too: According to a later Shiite tradition, a daughter of Yazdegerd III married. ( Shahr Banu ) al-Husain ibn 'Alī and became the mother of the fourth imam Ali Zain al-Abidin , which should give the Shiite imams a dynastic legitimation in addition to the Islamic one - on both sides, however, only in the female line (the idea that the right to rule is hereditary was also widespread among Muslims). It is very unlikely that this legend is based on fact. Nevertheless, her tomb is venerated in Rey .

Yazdegerd in Firdausi's Shāhnāme - Legend 50

Firdausi tells the following story in the 10th century in his famous epic Shāhnāme , which poetically processes the tales and legends about the kings of Persia : Yazdegerd III. (Yasgerd) had come to Merw, but the governor there named Mahuy had decided to murder the king and his companions. When the ruler and his troops attacked the Turks, his men no longer followed him into battle. Abandoned by all, Yazdegerd fled alone and hid in a mill where the miller found him. Although he noticed the man's wealth, splendid armor and beauty, he did not understand who it was. Yazdegerd asked him to get him the necessary items to be able to perform a prayer; In the process, however, the miller fell into the hands of the treacherous governor, who immediately recognized who was hiding in the mill and forced the miller, against the resistance of his own supporters, to murder Yazdegerd. So the miller stabbed the last great king from behind and brought the governor's crown and royal cloak. A group of Christian monks then washed the naked body out of mercy, after which they buried Yazdegerd in an improvised tower of silence in accordance with Zoroastrian regulations . How much truth is in this story cannot be decided.

literature

- Touraj Daryaee: Yazdgerd III's last year. Coinage and History of Sistan at the End of Late Antiquity. In: Iranistik 5, 2009, pp. 21–30.

- Touraj Daryaee: When the End is Near: Barbarized Armies and Barracks Kings of Late Antique Iran. In: Maria Macuch u. a. (Ed.): Ancient and Middle Iranian Studies. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 43–52.

- Richard Frye : The political history of Iran under the Sasanians. In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge 1983, ISBN 0-521-24693-8 , pp. 116-180, here pp. 172-176.

- Susan Tyler-Smith: Coinage in the Name of Yazdgerd III (AD 632-651) and the Arab Conquest of Iran. In: The Numismatic Chronicle 160, 2000, pp. 135-170.

Remarks

- ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth: Ṭabarī. The Sāsānids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen. Albany NY 1999, p. 410 with note 1017; see. also ibid., p. 409, note 1014.

- ↑ Nasir al-Ka'bi (ed.): A Short Chronicle on the End of the Sasanian Empire and Early Islam 590-660 AD Piscataway (NJ) 2016, pp. 76f., Note 198.

- ↑ Touraj Daryaee: When the End is Near: Barbarized Armies and Barracks Kings of Late Antique Iran. In: Maria Macuch u. a. (Ed.): Ancient and Middle Iranian Studies. Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 43–52.

- ↑ Touraj Daryaee: Yazdgerd III's last year. Coinage and History of Sistan at the End of Late Antiquity. In: Iranistik 5, 2009, here p. 25f.

- ↑ Touraj Daryaee: Yazdgerd III's last year. Coinage and History of Sistan at the End of Late Antiquity. In: Iranistik 5, 2009, here p. 21f. See also Nasir al-Ka'bi (Ed.): A Short Chronicle on the End of the Sasanian Empire and Early Islam 590-660 AD Piscataway (NJ) 2016, pp. 78-80 (with the documents there and various versions ).

- ^ Matteo Compareti: The last Sasanians in China. In: Eurasian Studies 2, 2003, pp. 197–213.

- ↑ See R. Todd Godwin: Persian Christians at the Chinese Court: The Xi'an Stele and the Early Medieval Church of the East. London / New York 2018.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Chosrau IV. |

King of the New Persian Empire 632–651 |

--- |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Yazdegerd III. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | یزدگرد (Persian); Yazdgird; Yazdgerd |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Great King of the Sassanid Empire (632–651) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | at 617 |

| DATE OF DEATH | 651 |

| Place of death | Merw |