End of antiquity

The question of the end of antiquity has occupied scholars for centuries.

In older research, the end of antiquity was often dated with the division of the empire in 395 , the deposition of the last Western Roman emperor Romulus Augustulus in 476, the defeat of Syagrius against Clovis 486/87 or the year 529, in which the first Benedictine monastery was founded and the Platonic Academy in Athens was closed.

In the research discussion of the last few decades, however, it has proven useful to set the end date significantly later. Closely related to the problem is the question of the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, which, especially in older research, was often equated with the end of antiquity. Common end dates for late antiquity and the beginning of the early Middle Ages are today the death of the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian in 565, the incursion of the Lombards into Italy in 568 or the beginning of Islamic expansion in 632.

Periodization problem

General

Any specification of an end date for antiquity requires the naming of the criteria according to which this epoch was defined. Among other things, the cultural and political unity of the Mediterranean region , the ethnic predominance of the Greeks and Romans , the slavery- based economy (an approach almost only represented by Marxist researchers, but which overlooked the fact that slavery was also widespread in the Middle Ages) certain educational traditions or polytheistic paganism are cited as characteristic of this epoch. The region under consideration must also be named, since not all developments occurred everywhere (or not everywhere at the same time). Apart from that, in the opinion of many historians, epochs are only agreements for the order of the otherwise unmanageable wealth of material of history. The Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce (1866–1952) even said that they were merely of “ mnemonic interest”. In addition, historical upheavals, which in retrospect can be bundled into the boundaries of epochs, were not necessarily perceived as such by contemporaries, since it is often only later generations that know the consequences of certain events and can recognize or establish causal relationships.

continuity

Establishing an end date for antiquity is particularly difficult because late antiquity must be seen as an epoch of transition. Late antiquity as the last phase of antiquity itself already represents a kind of “antiquity after antiquity”. On the one hand, there was still a clear continuity to the earlier antiquity, on the other hand, the world of the Middle Ages was already emerging. These two epochs were linked in particular by the interlocking of society with the Christian church, which prevailed in the 4th to 6th centuries. Culturally, late antiquity differs from the Middle Ages mainly in that at least the people of the educated upper class often still had access to the classical tradition ( paideia ) , as demonstrated by late antique authors such as Boëthius , Gorippus , Prokopios of Caesarea and Agathias in the sixth century is. With Cassiodor († 583), the transition from the ancient to the monastic book production of the Middle Ages began, and after the sixth century came with the civilian elite of the West and most of the ancient Latin literature based. Classical texts from antiquity were not copied again until the Carolingian Renaissance , insofar as they had survived the decline of literature between 550 and 800 (see Loss of Books in Late Antiquity ).

In the east, on the other hand, there was no such radical break in ancient tradition as in the west. The Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire still existed until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Byzantine studies therefore refer to roughly the same period, which is considered late antiquity on the soil of the Western Roman Empire, as early Byzantine. For the east of the empire both terms are practically synonymous. However, there are also considerable differences between the conditions in the fourth to sixth centuries and the subsequent Middle and Late Byzantine periods in Eastern Stream. In the Eastern Empire, in addition to the Arab expansion, the final displacement of the Latin official language by Greek around 625 should be seen as a significant turning point. Both events occurred during the reign of Emperor Herakleios , with whom the end of antiquity has therefore increasingly been associated in recent years. A little later, the political structure of the remaining empire changed fundamentally and lost its late Roman character. In recent years, Byzantine studies have been advocating that the actual Byzantine history should only begin after Justinian or Herakleios and that the three centuries before should be assigned to Roman history (e.g. Peter Schreiner , Ralph-Johannes Lilie argued against this ).

The Germans rich that the succession in the 5th and 6th centuries, the Western Roman Empire had begun, accepted as a rule for decades, the Eastern Roman suzerainty. Their rulers sought imperial recognition and the bestowal of Roman titles. Until the 6th century, only the emperor and the Sassanid great king could claim sovereignty for themselves. Only they had the right to stamp their image on gold coins: In the 6th century, most German kings only put their own portrait on silver coins. All of this only changed fundamentally in the 7th century, when the Eastern Roman emperors were too weakened by the attacks of the Persians and Arabs to continue to be active in the West. The Arab invasion finally destroyed the unity of the Mediterranean world, which was admittedly only conditional. Contacts between Constantinople and the West also loosened noticeably. Long-distance trade largely collapsed.

change

The attacks by the Arabs accelerated the fall of the late antique senate aristocracy in East Stream, and now also led to an economic crisis and a considerable decline in ancient education. The extensive military and economic collapse of the empire after 636 also brought the final end of the classical cities ( Poleis ) that had shaped the Mediterranean region from the archaic period (approx. 700 BC to approx. 500 BC) . Instead, many cities developed into a tiny fortified castron . The development of the Byzantine thematic order , which ultimately led to the dissolution of the division between military and civil administration, also meant a clear break with the late antique tradition in the administrative area.

The process of “transformation” that went hand in hand with the end of antiquity (see also Transformation of the Roman World ) was therefore in many ways associated with violence, destruction and economic decline. This was only recently emphasized by Bryan Ward-Perkins and Peter J. Heather in their more recent representations, some of which read like an alternative to the representatives of a long-term transformation process without major incisions, such as Peter Brown and Averil Cameron . Both - Ward-Perkins and Heather - admit, however, that antiquity in the Roman East, which only experienced economic decline after 600, lasted significantly longer than in the West. There was a material collapse there as early as the fifth century, an "end of civilization" (Ward-Perkins).

The research literature has now reached a size that can hardly be managed. On many points, however, no agreement has been reached so far, which is also due to the fact that archaeological research in this field often comes to different results than historical research, without the contradictions being resolved so far. Many of the old explanations have therefore become untenable, but it has often not yet been possible to replace them with convincing alternatives. One of the most heatedly discussed questions is the process that led to the extinction of the empire in the West. Even Henri Pirenne's view that the ancient unity of the Mediterranean world was destroyed only in the 7th century, still has followers. Simple answers and general statements have become almost impossible against the background of increasing research into late antiquity.

The end of antiquity in the regions

Britain

In Britain , the end of antiquity is traditionally set at the end of Roman rule and therefore relatively early. As early as 383, 401 and 407 , large parts of the Roman troops were withdrawn. When the Western Roman Emperor Honorius left the Roman inhabitants of the island to their fate in 410, they had to resort to self-help. There are some indications that the island came under Roman rule again briefly afterwards, but a request for help to the Roman general Aëtius in 446 is the last literarily attested sign of Roman presence in Britain. In the following decades, Christianity also largely died out in many regions. The Picts first poured into the power vacuum left by the Roman soldiers from the north of the island.

The Angles , Saxons and Jutes , who were probably called for help around 440 by the Romanized population (but maybe even earlier, in the late 4th century) , who were settled as foederati , rebelled at an unspecified point in time and after long battles finally took the entire country (excluding Wales, Cornwall and Scotland), with many locals appearing to have joined them. The population in West Great Britain seems to have tried for a long time to hold onto Roman structures and contacts with the continent, and apparently some of their leaders initially even claimed imperial dignity - the parents of Ambrosius Aurelianus are said to have "worn the purple". For a long time, numerous Celtic-Roman and Germanic “ warlords ” fought against each other in alternating coalitions in this “sub-Roman” Britain , until some larger principalities and small kingdoms were formed around 700.

The end of antiquity in Britain, as in the rest of the empire, was not a single event, but a long process, which, however, experienced at least a major turning point with the evacuation of the island by the Roman army. However, Latin inscriptions were still occasionally placed in Wales in the 6th century, which are even correctly dated to consuls . For the decades around 540, the time of Justinian , archaeological finds show that there was trade between West Britain and the East , and literary evidence also indicates that contacts with the Mediterranean region still existed at that time. The assumption, which has long been taken for granted, of the sudden end of antiquity in Britain can in any case hardly be maintained in view of the research carried out in recent years, even if the archaeological findings suggest that in terms of material culture around 400, a decline began in many places. The fact that Christianity, as the Catholic tradition teaches, also disappeared and only came back to the island under Gregory the Great in 597 is now doubted by several researchers.

Gaul

In Gaul , too , the end of antiquity is closely linked to the end of Roman rule. The last representatives of these are probably the magister militum Aegidius and his son Syagrius , possibly also the comes Paulus , whose exact function is unknown. The Romanized upper class of Gaul competed more strongly than before with that of Italy from about 400 on and tried again in 455 to enforce one of their own as emperor in the form of Avitus . After the failure of Avitus and the death of his successor Majorian , who had once again resided in Gaul, alienation escalated and the Romans of Gaul increasingly turned away from imperial headquarters in Italy. Aegidius and Syagrius were already regarded by the Franks as independent "kings of the Romans". The fact that Germanic rulers no longer only accepted Roman titles but, conversely, Roman governors were designated with Germanic titles (whether they accepted these themselves is uncertain and at least doubtful) shows the changed balance of power, even if the Gallo-Roman culture around 450 still experienced one last late bloom. In 476 Syagrius did not recognize the new lord of Rome, the Skiren Odoacer , and asked the Eastern Roman emperor Zenon for help. However, the latter was obviously unable to send support to the last Roman representative in Gaul, and was possibly even allied with his rival Childeric I.

In 486 or 487 the Frankish rex Clovis I , Childeric's son , finally conquered the kingdom of Syagrius. He fled to the Visigoths , but was handed over to Clovis and killed. According to many researchers, the fact that the Gallic Christians accepted Clovis as the successor or representative of the Roman rulers marks the end of antiquity in Gaul. Others, however, let the late antique phase of Gaul end around 500 with Clovis' baptism and 561 with the death of King Chlothar I , and some historians even count the following almost two hundred years until the deposition of the last Merovingian Childeric III. in the year 751 to late antiquity.

Hispania

In Hispania , the end of antiquity is to be set at 460 at the earliest. This year, Majorian, was the last time a Western Roman emperor set foot on Hispanic soil, but his campaign against the Visigoths had no major impact. In 468 the Visigoths under King Eurich broke away from the imperial union, Hispania was now firmly in Germanic hands until the 6th century. It was not until 533 that the troops of the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian conquered the Balearic Islands and Gibraltar . In 553, Córdoba , Carthago Nova ( Cartagena ) and Málaga also came under Eastern Roman control. Justinian even appointed his own magister militum Spaniae , who was responsible for the protection of the southern Spanish regions of eastern Spain. By 625 these were lost to the Visigoths. After the Suebi had ruled northern Spain for a long time , the end of antiquity had now also arrived in southern Spain. Traces of Roman culture and legal tradition among the Visigoths (cf. the Codex Euricianus ) and the development of a Romance language, Spanish , still point back to antiquity. For this reason, some researchers assume a Roman-Gothic symbiosis on the Iberian Peninsula and only put the end of late antiquity here with the Moorish conquest in 711. The majority of ancient historians, however, place the average in the 6th century, for example with the conversion of the Visigoths to Catholicism in 589. The last struggles for the reintroduction of Arianism did not end until King Witterich's death in 610. In Medieval Studies, late Roman Hispania ( from the 5th century) on the subject of investigation; It is similar with Gaul and Italy.

North africa

The beginning of the end of antiquity for Africa came in 429, when the Vandals under Geiseric conquered large parts of the province. In 431, Hippo Regius , the hometown of Augustine , fell, and in 439, Carthage , which was still one of the largest cities in the Mediterranean, fell. In 442, Geiseric was officially given by Emperor Valentinian III. recognized as the semi-sovereign lord of North Africa. In 455 the Vandals even plundered the city of Rome . Geiseric successfully prevented the landing of a Roman fleet in Africa several times. Nevertheless, ancient traditions continued to be maintained even under the Germanic rulers; so authors like Priscian , Fulgentius or Gorippus worked among the Vandals or learned their training during this time. In 533/34 the Roman general Belisarius was able to forcibly win back North Africa. Emperor Justinian I immediately appointed a Praetorian prefect and an army master for the conquered area. However, it was not until 551 that Africa was completely secured for the Eastern Roman Empire.

There was probably only a limited resurgence of ancient Roman culture, but recently excavators have come to a much more favorable assessment than earlier researchers. For example, over 100 churches, some of them large, can be identified that were built after 534. In any case, Herakleios could still use Africa in 608/10 as the basis for his seizure of power in the Eastern Roman Empire, and around 620 there were even plans for a time to make Carthage an imperial residence. The latest research therefore tends to no longer speak of a decline for North Africa in the 5th and 6th, but rather of a rapid collapse in the first half of the 7th century. With the invasion of the Arabs from 647, the ancient world ended here for good. Carthage fell in 698, and North African Christianity soon died out and many cities were abandoned.

Italy

The end of antiquity in Italy was a process that began with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire after the murder of the army master Flavius Aëtius by Emperor Valentinian III. 454 began: After the emperor himself had been assassinated in 455, with which the Theodosian dynasty had come to an end, none of his successors succeeded in asserting himself. From 461 at the latest, Italy was effectively ruled by General Ricimer ; some of the emperors he appointed were little more than puppets: power in Italy now lay predominantly with the commanders of the army, which meanwhile consisted mostly of non-Roman foederati . With the deposition of the last Western Roman emperor Romulus Augustulus by the military leader Odoacer in 476, this process reached its first climax. However, the ancient structures still existed, there was still a Senate and a City Prefect . Also consuls were still elected and formally the country was under imperial rule continue. Odoaker's successor, the Ostrogoth Theodoric (493-526), surrounded himself with Roman advisers in high positions.

Theodoric's successors soon came into conflict with the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian . The reconquest of Italy, initiated by Justinian from 535, initially seemed to revive ancient culture. However, the Eastern Roman conquests did not last. Above all, however, the (second) Gothic War since 541 brought the end of the Western Roman senatorial class, which had been a bearer of ancient culture. The western Roman imperial court in Ravenna, orphaned since 476, was dissolved with its offices in 554 by Justinian, with which the ancient administrative structures of Italy also disappeared. Attempts to rebuild the infrastructure came to a sudden end shortly afterwards: with the incursion of the Lombards in 568, the last train of the late ancient migration , the final phase of antiquity in Italy was heralded, but this lasted until the 7th century. The last ancient monument on the Roman Forum in Rome is the column of the Eastern Roman emperor Phocas (602–610); one last offensive in Italy and one last relocation of the imperial residence to the west (briefly Rome, then Syracuse) under Constans II failed in the 660s.

Roman Orient

In the Roman Orient, which was organized in the dioceses of Aegyptus and Oriens , the end of antiquity came late - with the Islamic expansion from 632 onwards. However, the end of Roman rule had already become apparent at the beginning of the 7th century when Persian troops housed King Chosrau II conquered large parts of the area and, above all, caused enormous economic damage. The Holy Cross , one of the most precious Christian relics , also fell into the hands of the Persians. The time of late ancient Greek and Syrian literature, which had produced noteworthy religious and profane works in the 6th century, also ended. Emperor Herakleios was able to defeat Chosraus' troops in 627 and regain the Orient provinces for the empire in 629/630, but he could not assert them against the invading Arabs . These had conquered the Persian Sassanid Empire within a few years and now turned against the Eastern Roman Empire. The Syrian metropolis Damascus fell in 635 , and the Egyptian capital Alexandria in 642 . Within the next few decades, Islam and the Arabic language established themselves in the formerly Roman Orient, and antiquity had come to an end here too, although the transitions here were much more fluid than elsewhere.

Persia

In Persia, the end of antiquity coincided with the collapse of the Sassanid Empire . The neo-Persian Sassanid Empire, which had replaced the Parthian Empire in 224 , had been an equal opponent of the Roman Empire throughout late antiquity (see also Roman-Persian Wars ). Under Chosrau II (590–628) it once again reached a new size. The Persians conquered Egypt and Syria, which had been ruled by the Romans for more than six centuries. However, when the siege of Constantinople failed in 626, it became clear that the Sassanid Empire had passed its zenith. After a defeat against the Eastern Roman emperor Herakleios at Nineveh and the death of Chosraus II in 628, none of the rapidly changing rulers could build on the former power of the Sassanids. The ailing empire was ultimately unable to cope with the Islamic expansion that began after the death of Muhammad , although the Persians offered stiff resistance. Two devastating defeats at Kadesia 638 (the exact year is disputed) and at Nehawend 642 sealed Persia's fate. At the latest with the death of the last Persian great king Yazdegerd III. in 651 the end of antiquity had come here too.

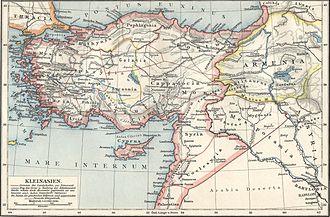

Asia Minor

In Asia Minor , the end of antiquity came relatively late. It is difficult to give an exact end date here. The transition from the late ancient Eastern Roman Empire to the Middle Byzantine Empire took place in the 7th century. At first the peninsula was threatened by the Sassanids, but the Emperor Herakleios was able to repel them, then from the 630s onwards by the Arabs. Under the influence of these external threats, the administrative structure of the empire changed. In Asia Minor the themes of Anatolicon and Armeniakon emerged , in which military and civil violence were once again connected, while late antiquity was marked by a separation of these powers. In older research this administrative reform was ascribed to Herakleios, but today it is more associated with his grandson Konstans II; the beginnings of the topics are often explained in research as an attempt to re-establish the army groups that defended Armenia and the Orient (Greek Anatolé ) up to around 640 . In Asia Minor Christianity had for a long time largely triumphed over the ancient pagan cults (under Justinian, John of Ephesus had 80,000 Old Believers baptized), and the Latin language was now finally superseded by the Greek. Cultural life was also subject to this transformation process: many cities fell into disrepair in the 7th century or were transformed into small fortress towns, known as kastra .

Balkans

In the Balkans , which in late antiquity was divided into the three dioceses of Macedonia , Dacia and Thracia , the end of antiquity is to be set rather late. With money and negotiating skills, the Eastern Roman emperors repeatedly managed to divert attacking Germanic tribes to the west, even if the Balkan provinces were repeatedly devastated in the 5th and 6th centuries. After Justinian , however, the Eastern Roman Empire lost more and more of its ancient character. The importance of Latin was now pushed back in favor of Greek in the Balkans. The Greek poleis and the Roman cities, which had shaped the Balkans for centuries, lost more and more of their importance (see Kastron ). At the same time, a new enemy threatened the Balkan provinces with the Slavs (see also slave lines ), who moved to a permanent settlement in the Balkans from around 580, which could only be temporarily prevented by the Balkan campaigns of Maurikios . The end of antiquity is to be set here at the turn of the 7th century. It was finally sealed by several factors: the conquest of the Slavs in the Balkans , the development of the Eastern Roman Empire to the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Herakleios and the departure from the ancient administrative structure with the introduction of the thematic constitution .

Danube region

In the Danube provinces of the Western Roman Empire, Raetia , Noricum and Pannonia , the end of antiquity is to be equated with the end of a Roman administration. In Pannonia it occurred relatively early, although a settlement continuity of the Romanesque population up to around 670 can be proven. Germanic and Hunnic federations were already settled here at the end of the 4th century . Roman rule could only be restored for a few years around 410, until Pannonia came under the control of the Huns for decades . Around the middle of the century it became the starting point of Attila's offensives . The Romans stayed longer in Noricum . As the vita of St. Severin von Noricum shows, the area was only cleared from them in 487/88 under Odoacer . However, according to most historians, large parts of the Roman population did not leave Noricum even under Germanic rule. The development in Raetia was similar, but the southern part of the former province remained Roman under Odoacer's successor Theodoric . The end of antiquity here is likely to be around 506 with the permanent settlement of the Alamanni , if not not until the end of Ostrogothic control of the area around 535; many details of the late ancient history of Raetia are, however, controversial in research.

Traditional ending dates

476

The division of the empire after the death of the Roman emperor Theodosius I in 395 was seen as a decisive turning point in very isolated cases in older research . But much more often the end of late antiquity was equated with the deposition of Romulus Augustulus by Odoacer and the end of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476. This view is especially widespread in older doctrines, for example in Otto Seeck's six-volume story of the fall of the ancient world . Nonetheless, disagreement arose early on in specialist circles. Ernst Kornemann and later Adolf Lippold , for example, already argued differently . Even Alfred von Gutschmid (1831-1887) set the end of antiquity later.

The idea of the epoch year 476 can only be grasped in the sources a good 40 years later, for the first time in the case of the Eastern Roman and imperial official Marcellinus Comes . He wrote around 520: The western empire of the Roman people perished with this Augustulus. Similar assessments can be made for Eugippius (who assumed around 510 that the old Roman Empire no longer existed, at least in the Danube region), Prokopios and Jordanes (both around 550). They were followed by the early medieval chroniclers Beda Venerabilis and Paulus Diaconus .

Today it seems more than questionable whether the contemporaries of the year 476 also saw the deposition of Romulus Augustulus as a turning point. From then on there was no longer an emperor in Ravenna , but this only meant that the rulership rights were now just passed to the (Eastern) Roman emperor in Constantinople, who actually intervened repeatedly in the west in the following period. There had also been vacancies in the Western Empire several times before, and it was not foreseeable that this would be permanent. In fact, the appointment of a new Western Roman emperor was repeatedly considered in the following decades. And Emperor Justinian also wanted to actually realize his claims on the West and enforce them militarily.

In more recent research, the year 476 is therefore no longer as important as it used to be. It is more likely that 476 was only brought into play around 520 as an epoch year in order to provide the Eastern Roman emperors with legitimation to bring the orphaned West under their direct rule. Basically, the question arises whether the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the end of the Empire in the West, as purely political events, are at all suitable to mark an epoch boundary: In social and cultural-historical terms, the deposition of the Western Emperor is at least for Italy, Gaul and Spain, not to mention Eastern Stream, no discernible turning point. Most of the current representations of late antiquity therefore extend beyond 476.

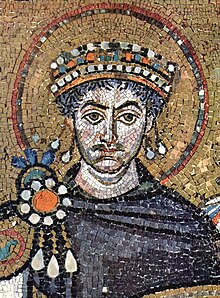

565

One often sees an important turning point today at the end of Justinian's reign (527-565). This was still completely in the tradition of the ancient Roman emperors, which is clear, among other things, in his universal concept of rule. Justinian was the last Augustus to have Latin as his mother tongue. He also pursued a policy that apparently actively aimed at restoring the empire within its old borders ( Restauratio imperii ) , which in some cases even succeeded in the short term, while his successors no longer pursued this policy. Culturally, there was a certain break in his reign in so far as the emperor ordered the closure of the Platonic Academy in 529 (531?) . With this, a tradition of pagan-philosophical education spanning more than nine hundred years came to an end, which is why especially academics oriented towards educational history saw this as the end of antiquity. However, even after 529, some important philosophers continued to work in the ancient tradition, such as Simplikios , and the Alexandrian School continued into the 7th century: One can therefore hardly speak of a real break, the closure of the School of Athens is primarily symbolic.

Today's ancient historians, especially in Germany, therefore usually classify the end of antiquity around thirty years later: The last great move of the late ancient migration , the Lombards invasion of Italy, took place in 568, only three years after Justinian's death, so that the The 560s mark a certain turning point for the entire Mediterranean region. This results in the currently most common (in Germany, France and Italy) limitation of the epoch, Justinian's year of death 565. This year was already proposed in humanism , in particular by Carolus Sigonius in his Historiae de occidentali imperio a Diocletiano ad Iustiniani mortem, published in 1579 . In modern times it was viewed by Gutschmid in particular as the end date of antiquity and has been very well received in German-language research in recent years (see, for example, Alexander Demandt , Heinz Bellen , Jens-Uwe Krause , Jochen Martin or Hartwin Brandt ).

632

Henri Pirenne saw the incursion of the Arabs into the Mediterranean area beginning in 632 and its economic consequences as the turning point between the ancient world and the Middle Ages. A new era had already begun for the Arab Muslims with the Hijra in 622 . Pirenne's thesis that it was only Islamic pirates who destroyed the ancient "unity of the Mediterranean world" is now considered to be refuted, as it is not sufficiently supported by the sources. It is apparently true, however, that in the 7th and early 8th centuries there was a marked decline in economic, cultural and political relations between the east and west of the Mediterranean and a persistent economic depression in the west, if not from the reason assumed by Pirenne (see also the so-called Pirenne thesis ). Around 600 there was evidence of lively trade throughout the Mediterranean, although it was less intense than in previous centuries, but by no means insignificant. The fact that the contacts between East and West were still quite close at the beginning of the seventh century is hardly denied today, especially in Anglo-Saxon research: “It is very clear that the sixth century did not in fact see a final split between East and West. "

The Arab attacks represented a massive turning point for the Eastern Roman Empire, as the empire was essentially limited to Asia Minor and the Balkans within a very short time and, under external pressure, also got rid of many ancient Roman traditions inside. The late Roman phase of the Eastern Roman Empire only ended under Emperor Herakleios (610–641). The remains of it were then transformed into medieval Byzantium .

Overall, therefore, especially in the Anglo-American region, there is a tendency to set the end of antiquity at the earliest with the end of Justinian's reign ( e.g. Averil Cameron and John Bagnell Bury ; somewhat idiosyncratic Arnold Hugh Martin Jones in 602 with the death of the emperor Maurikios ); as in recent years (also because of the more favorable sources) one has dealt more and more with the east of the Roman Empire, where ancient structures, as mentioned, lasted longer than in the west, but many Anglo-Saxon scholars prefer even later dates. The last volume of the new Cambridge Ancient History covers the years 425 to 600 (partly up to 640), and the Routledge History of the Ancient World also ends in the year 600. The important Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire and the more recent account by Stephen Mitchell extend late antiquity to the death of Herakleios in 641; Averil Cameron even covers the years up to 700 in the second edition of her standard work The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity , published in 2011 .

But even in German-speaking countries, especially younger researchers are now increasingly going beyond 565 (see above). Ernst Kornemann , who earlier than other German researchers pleaded for a broad transition period between antiquity and the Middle Ages ("... period with the Janus head ...") , already had here in his great world history of the Mediterranean and in his Roman history the time of Herakleios to late antiquity counted. Today's researchers like Hartmut Leppin or Mischa Meier follow him in this.

For Eastern Era, an extension of the epoch to 632 or 641 does indeed make sense and is increasingly gaining acceptance, since the Arabian invasion (see Islamic expansion ) marked the decisive turning point. The Arab troops not only conquered the Roman Orient, but also destroyed the New Persian Empire of the Sassanids . The Sassanid Empire was an important power factor throughout late antiquity as the second great power next to Rome and is therefore included by some ancient historians (such as Josef Wiesehöfer , Erich Kettenhofen , Ze'ev Rubin or Michael Whitby ) in the research of the epoch. For ancient historians, on the other hand, whose focus is on Western European history, the events after 568 are of little interest.

Transition to the Middle Ages

The transition from Late Antiquity to the European Early Middle Ages took place slowly in many places. In Italy, for example, the time of Theodoric the Great has to be counted as antiquity rather than the Middle Ages ; but it is impossible to fix an exact date for the end of antiquity. As already mentioned, ancient culture can be traced in Italy until the Lombard invasion, and the Western Roman Senate only disappears from the sources towards the end of the sixth century. In a similar way, the early Merovingians built on the ancient legacy in Gaul , which was then developed independently. One has to speak of a transitional phase that lasted for different lengths of time depending on the region. In the west, especially around 500, in the east around 600, there was a relative accumulation of breaks and drastic changes. It makes little sense to set the epoch boundary later than the 6th (west) or 7th century (in the east).

The problem can also be reversed: Many medievalists who deal with the early Middle Ages (such as Friedrich Prinz , Hans-Werner Goetz , Patrick J. Geary , Walter A. Goffart , Herwig Wolfram , Chris Wickham , Ian N. Wood and others) take action go back to late antiquity and consider the time from the 4th century onwards to explain the changes in the early Middle Ages. It is beyond doubt that, despite many breaks, there were just as many lines of continuity between antiquity and the Middle Ages.

It should also not be forgotten that in the Middle Ages, conscious attempts were made to tie in with antiquity. There had been no break in people's consciousness, one still believed to be in late antiquity, so to speak. A key term here is the Translatio imperii , the transition from the Western Roman imperial dignity to the Franks under Charlemagne and the "Germans" under Otto the Great . The Holy Roman Empire carried this name until its end in 1806 and saw itself as a direct successor to the late ancient emperors. From a cultural point of view, too, there have been repeated attempts to revive ancient ideas: The Carolingian Renaissance around 800 saved many ancient works for posterity. The most powerful of these renaissances (French "rebirth") of antiquity was then the Italian renaissance of the 14th and 15th centuries, which ushered in the modern era .

literature

- Clifford Ando: Decline, Fall, and Transformation . In: Journal of Late Antiquity . tape 1 , 2008, p. 31-60 .

- Henning Börm : The Western Roman Empire after 476 . In: Henning Börm, Norbert Ehrhardt , Josef Wiesehöfer (eds.): Monumentum et instrumentum inscriptum. Inscribed objects from the imperial era and late antiquity as historical evidence . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-515-09239-5 , pp. 47-69 ( online ).

- Henning Börm: Westrom. From Honorius to Justinian . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-17-023276-1 .

- Wolfram Brandes : Herakleios and the End of Antiquity in the East. Triumphs and defeats . In: Mischa Meier (Ed.): They created Europe. Historical portraits from Constantine to Charlemagne . CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55500-8 , p. 248-258 .

- Peter Robert Lamont Brown : The World of Late Antiquity AD 150-750 . Thames & Hudson, London 1971, ISBN 0-500-33022-0 (several reprints).

- Alexander Demandt : The Fall of Rome. The dissolution of the Roman Empire in the judgment of posterity . 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66053-5 .

- Alexander Demandt: The late antiquity. Roman history from Diocletian to Justinian 284–565 AD (= Handbook of Classical Studies . 3rd section, 6th part). 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55993-8 , p. 589-593 .

- Paul Fouracre (Ed.): The New Cambridge Medieval History . tape 1 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 0-521-36291-1 .

- John Haldon: Byzantium in the Seventh Century. The Transformation of a Culture . 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997, ISBN 0-521-31917-X .

- James Howard-Johnston : Witnesses to a World Crisis. Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-920859-3 .

- Guy Halsall : Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376-568 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-43491-1 .

- Peter J. Heather : The Fall of the Roman Empire . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-608-94082-4 (English: The Fall of the Roman Empire . Translated by Klaus Kochmann, review ).

- Mischa Meier : Eastern Byzantium, Late Antiquity and Middle Ages. Reflections on the “end” of antiquity in the east of the Roman Empire . In: Millennium . tape 9 , 2012, p. 187-253 .

- Stephen Mitchell: A History of the Later Roman Empire. AD 284-641 . 2nd, revised edition. Blackwell, Oxford et al. 2014, ISBN 978-1-118-31242-1 .

- Bryan Ward-Perkins : The Fall of the Roman Empire and the End of Civilization . Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2083-4 (English: The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization . Translated by Nina Valenzuela Montenegro, review ).

- Chris Wickham : Framing the Early Middle Ages. Europe and the Mediterranean, 400-800 . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2005, ISBN 0-19-921296-1 .

Web links

- Medieval Sourcebook: The End of the Classical World

- Conference report From late antiquity to the early Middle Ages: continuities and breaks, concepts and findings

Remarks

- ↑ For further information on the literature of the late antiquity see Spätantike # Kulturelles Leben .

- ↑ See Lilies review in: Byzantinische Zeitschrift 101, 2009, pp. 851–853. Discussion with Mischa Meier : Eastern Byzantium, Late Antiquity and Middle Ages. Reflections on the “end” of antiquity in the east of the Roman Empire . In: Millennium . tape 9 , 2012, p. 187-254 .

- ↑ Bryan Ward-Perkins, The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization ; Peter J. Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire .

- ↑ For the background, see Pirenne thesis and Pirenne's books Mohammed and Charlemagne (English-language new edition Dover, Mineola 2001, ISBN 0-486-42011-6 ) and Economic and Social History of Medieval Europe .

- ↑ Evangelos Chrysos: The Roman rule in Britain and its end. In: Bonner Jahrbücher 191 (1991), pp. 247-276.

- ^ Gildas , De Excidio Britonum 25.

- ↑ Gregory of Tours , Historiae 2,12; 2.27.

- ↑ Cf. for example the letter of Remigius of Reims ( Monumenta Germaniae Historiae epp. 3,113): The bishop congratulates Clovis on taking over the "administration" of the province of Belgica secunda .

- ↑ See for example Patrick J. Geary: Die Merowinger , Munich 2004, pp. 225-230.

- ^ Cf. Claude Lepelley: La cité africaine tardive . In: Jens-Uwe Krause, Christian Witschel (Ed.): The city in late antiquity. Decline or change? Stuttgart 2006, pp. 13-31.

- ^ Henning Börm: Westrom. From Honorius to Justinian . Stuttgart 2013, pp. 135-139.

- ↑ For a more detailed description see Sassanid Empire # The End of the Sassanids .

- ↑ See Roman-Persian Wars # Pax Persica? Chosrau II and the counterstrike of Herakleios .

- ↑ Current overview from Roland Steinacher: Rome and the barbarians. Peoples in the Alpine and Danube region (300-600). Stuttgart 2017.

- ^ The Vita Sancti Severini by Eugippius was published in 1898 by Theodor Mommsen, among others. Current edition: Reclam, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-15-008285-4 . See also Friedrich Lotter: Severinus and the end of Roman rule on the upper Danube . In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 24, 1968, pp. 309–338

- ↑ To the end of the empire in the west: Marinus Antony Wes: The end of the empire in the west of the Roman Empire . The Hague 1967.

- ↑ The history of the fall of the ancient world first appeared in 1895–1921 and is currently available in a special edition introduced by Stefan Rebenich (Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2000, ISBN 3-89678-161-8 ).

- ^ Theodor Mommsen (ed.): Chronica Minora II, 91.

- ^ Eugippius, Vita Sancti Severini 20; Prokopios, Bellum Gothicum 1,12,20; Jordanes, Romana 322; Getica 242.

- ↑ Beda Venerabilis: Chronica Minora 3,305; 3.423; Paulus Deaconus, Historia Romana 15.10.

- ↑ Demandts Late antiquity extends to 565.

- ↑ Brandt's End of Antiquity spans the period from 284 to 565.

- ↑ See Michael McCormick: The Origins of the European Economy. Communications and Commerce, AD 300-900 . Cambridge 2001.

- ^ Averil Cameron : Old and New Rome. Roman Studies in Sixth-Century Constantinople . In: Philip Rousseau, Manolis Papoutsakis (ed.), Transformations of Late Antiquity . Aldershot 2009, p. 15ff. (here: p. 23). Mischa Meier has a different opinion : Anastasios I. Stuttgart 2009.

- ^ Ernst Kornemann: Roman history. Volume 2: The Imperial Era (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 133). 7th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-520-13307-5 , p. 371.

- ↑ Prince worked on European foundations of German history (4th-8th centuries) until shortly before his death . In: Alfred Haverkamp, Gebhardt. Handbook of German History 1: Perspectives on German History during the Middle Ages , Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-608-60001-9 .

- ↑ Besides Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages, see also his new overview work: The Inheritance of Rome. A History of Europe from 400 to 1000 . London 2009.