Loss of books in late antiquity

The book losses in late antiquity (the epoch between the late 3rd and the late 6th centuries ) represent an irretrievable loss for the cultural heritage of classical antiquity . Due to the loss of tradition of much of ancient Greek and Latin literature, the number of works, which have survived into modern times , extremely small. Most of the texts that have come down to us have been preserved in medieval copies; very few original text documents from antiquity have survived.

The reasons for this massive loss are varied and controversial. A turning point can be seen in the so-called Imperial Crisis of the 3rd century . There is evidence of systematic destruction of Christian writings during the persecution of Christians as well as pagan ("pagan") writings in the course of the Christianization of the Roman Empire . Other causes are likely to be found in the cultural decline and the turmoil of the Great Migration Period, especially in the West, when numerous book holdings were likely to have fallen victim to warlike destruction and the remaining cultural bearers of tradition disappeared with the educated elites. Changes in the media - so the definition of writing material papyrus to parchment and the scroll to the codex - and the literary canon and the school system were additional barriers. The transmission of works ended if they were not rewritten in the new medium.

While the literary tradition of antiquity was maintained in the Byzantine Empire up to the fall of Constantinople - albeit in different forms - at the end of antiquity in the Latin West only a small elite of well-to-do and educated people preserved the literary heritage of antiquity in a smaller selection. To this group belonged Cassiodorus , who came from a senatorial family , who in the 6th century collected the remains of ancient literature that he could still reach and founded the monastic book production of the Middle Ages in Vivarium . In the 7th and 8th centuries in particular, manuscripts by both classical authors and some Christian authors were partially deleted and rewritten. Among the sparse inventory of these oldest Latin manuscripts that are still in existence today, most manuscripts with texts by classical authors are only preserved as palimpsests . The subsequent Carolingian renaissance , in which the production of manuscripts for classical texts was revived, was therefore all the more important for tradition. There were many reasons for making palimpsests. Practical considerations were usually decisive, such as the preciousness of the material, font changes or a change in literary interest, and in the case of classical and heretical texts probably also religious motifs.

The consequences of the loss of large parts of ancient literature were considerable. It was not until the invention of the printing press in the 15th century that the ancient texts that had survived gradually became accessible again to a larger audience. Many of the achievements of modern times were directly or indirectly inspired by these writings. Libraries of the modern age probably did not regain their holdings until the 19th century.

The book inventory of antiquity and its tradition

Due to the tradition in libraries, i.e. before the papyrus finds from 1900, about 2000 author names were known from Greek literature before the year 500, but at least parts of their writings were only preserved from 253 authors. For Roman literature there were 772 authors' names, of which 144 authors have preserved writings. This led to the popular estimate that less than 10% of ancient literature has survived. The almost 3000 author names represent a minimum number, namely those mentioned in traditional texts. In addition to many Christian ones, these are predominantly classic school authors, but not the entire inventory of ancient titles. In relation to the entire period of antiquity, however, the Christian authors only represented a relative minority.

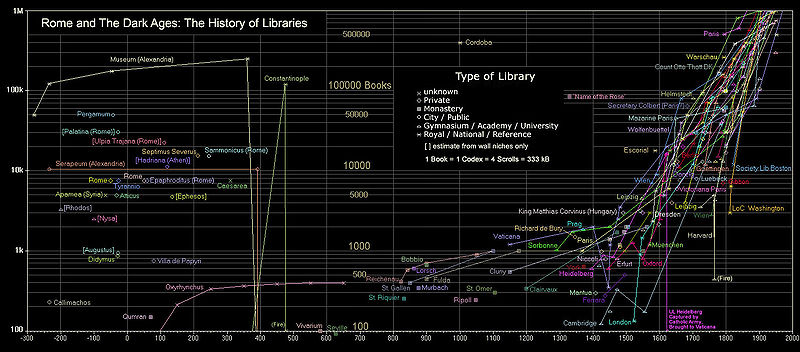

An assessment of the ancient holdings of titles and books is only possible indirectly through the history of the library. The most famous library of antiquity, the Library of Alexandria , grew from 235 BC. BC to 47 BC From 490,000 to 700,000 scrolls, mostly in Greek. One role corresponded roughly to a title (see book ). The title production in the Greek world was therefore at least 1100 per year. Extrapolated to the year 350, this would result in a stock of around one million titles.

These statistics of the library holdings, as far as they are known or extrapolated, show the considerable break in the history of transmission from antiquity to modern times. Accordingly, it was not until the 19th century that European libraries regained holdings comparable to those of the ancient libraries.

The extent of the Latin literature cannot be precisely determined, but could have reached a comparable order of magnitude. Since rather trivial works from the provinces probably did not find their way into the large libraries, the total inventory of ancient titles could also have exceeded the million mark very clearly. Assuming an average distribution of 10-100 copies, this would be a number of rolls or books in the tens of millions. Of these million books from before 350, not a single one has been preserved in a library. All sources from pre-Christian times, i.e. around 350, were probably only passed on as Christian editions, which have been available since the 3rd / 4th centuries. Century (in the west especially in the 4th century) were created.

The number of surviving ancient texts (without finds) has not yet been precisely determined. The order of magnitude should be around 3000, 1000 of them in Latin . Most of it is only available in fragments . The total volume of non-Christian text that has been handed down to us consists of less than 100 codices , at least in Latin . The break in the holdings of ancient titles is therefore considerable and could be on the order of one in 1000. According to this calculation, only 0.1% or only one in 1000 titles would have survived. This figure is obtained when one compares an estimated total inventory of titles of a few million with the several thousand surviving titles, or if one - regardless of this - the last ancient library of Constantinople , which burned down around the year 475 with 120,000 books, with the first known medieval library of Cassiodorus in the west compares the 576 who owned around 100 codices.

The loss of books

Ancient stocks

There were a large number of libraries in ancient times . Municipal public libraries and private libraries with 20,000 to 50,000 rolls are known both in Rome (29 public by 350) and in the provinces. During Caesar's visit to Alexandria, it was probably not the large library that was burned, but perhaps only a warehouse at the port with 40,000 rolls that could have been destined for export as annual production. What is certain is that Alexandria remained a center for books and scholars for a long time afterwards. The library of Alexandria already contained more than 490,000 scrolls in the Hellenistic period, the one in Pergamon 200,000 scrolls. At the latest in the imperial era, some cities should have reached this level, as a library was a status symbol.

There is no information about the holdings of the large libraries in Rome . Archaeologically, the size of wall niches for bookcases at the Palatina and Ulpia Trajana can be deduced from at least 100,000 rolls. Probably only the most precious roles were in it. The Pergamon library also had almost all of its holdings in storage rooms. Given the size of the buildings, the main libraries in Rome, like those in Alexandria and Athens, would each have held millions of rolls. With such a geographical distribution of ancient literature, individual events such as the loss of a library could not represent a major problem for tradition.

Possible causes of loss

The writings of some ancient authors are likely to have been destroyed before late antiquity , as the example of Titus Labienus shows, whose writings were burned on the orders of Augustus for insulting majesty . However, it is likely to be a minority.

The paraphrase / rotting thesis is particularly widespread in older overview representations, according to which papyrus scrolls were parchmented on parchment codices around 400. In the Christian-dominated time or even earlier, society then lost interest in non-Christian roles. They were therefore no longer copied and rotted in libraries over the course of the Middle Ages , while the more durable parchment codices survived.

Also, the research literature often does not reveal how great the loss was. The overall account of the transmission history by Reynolds and Wilson ( Scribes and Scholars ), for example, gives no information on the size of the libraries of Cassiodorus and Isidore of Seville . Lost writings are mentioned today that were still cited around 600 without discussing whether they were cited from the original works or from excerpts that were already available, as has been proven for Isidore. The assumption is widespread that in addition to or even before the destruction of the Migration Period, Christianization was a factor in the loss of ancient literature.

Papyrologists doubt the assumption that papyrus has a shorter shelf life. Roberts and Skeat, who examined the subject in The Birth of the Codex 1983, found that the papyrus is no less durable than parchment under normal storage conditions:

“The durability of both materials under normal conditions is beyond doubt. One could refer to the large number of papyri that have been found that show a long-lasting preservation of the writing, but this is no longer necessary since the myth that papyrus is not a durable material was ultimately authoritative and - one should hope - finally refuted by Lewis has been."

Newer studies therefore assume a long shelf life for the papyrus. Around 200 one could read a 300 year old papyrus scroll from the founding time of Roman libraries in a library in Rome. The material would certainly have had to withstand over 400 years. But after 800, the many ancient roles no longer existed, as can be deduced from the catalogs and the copying activities of that time. In both the Latin West and the Greek East, from 800 onwards, it was only possible to fall back on codices that were written after 400.

In addition, the Codices Latini Antiquiores (CLA) contain at least 7 papyrus codices which have survived at least in part in libraries from the period between 433 and 600 until today. One, CLA # 1507, around 550, is in Vienna and still has 103 pages. If these could last for 1500 years, the many others should have lasted for at least 400 years. The loss cannot be explained by the insufficient shelf life of papyrus, scrolls or codices.

It looks as if, after the rewriting to codices after 400, suddenly a lot fewer books and these were only produced in the form of codices made of parchment. The scrolls found in Oxyrhynchos (approx. 34% of the total papyri, 66% were documents) show brisk book production in the 2nd and 3rd centuries (655 and 489 items) and a massive slump in the 4th and 5th centuries (119 and 92 pieces) as well as only a small production afterwards (41, 5 and 2 pieces after the 7th century, when the city also disappeared). However, it must be left open to what extent this is due to a possible population decline.

The CLAs show a similar picture for Latin Europe. Thereafter, around 150 codices were passed down from 400 to 700 in Latin Europe outside Italy. Of these, 100 are only in France. This is also confirmed by the further palaeography after the period of the CLA. The holdings of the large monastery libraries around 900 in the Lorsch , Bobbio and Reichenau monasteries , each containing around 700 codices, almost all date from the period after 750 and thus show the so-called Carolingian Renaissance . For many ancient books, the oldest surviving copies date from this period. At that time books from the 5th century were probably copied that are no longer preserved today. For the period up to 800, the CLA records only 56 traditional books, only 31 of them from the 5th century. (For details on the geographical distribution, see the main article: Codices Latini Antiquiores )

So there was not just a selection and selection in the phase of paraphrase, but an extremely reduced book production in general. If before 300 it reached the order of magnitude of at least 10,000 per year, after 400 in the Latin West it was an average of 10 per year.

The parchment can be explained by the fact that because of this low production there was no longer any need for the cheap papyrus and the previously more noble, but now more readily available, parchment was preferred. There was a “demand-related selection process”. Papyrus was only used in exceptional cases for books or documents and was hardly available in the Latin area from around 600 onwards.

Affected subject areas

The scientific and technical knowledge in late antiquity was certainly so extensive and complicated that oral transmission was no longer possible. If this knowledge was associated with non-Christian names and views, it could compete with Christianity. In the non-Christian Roman culture, pornographic representations of all kinds were also common in everyday life, which were despised by Christianity. Around 200, the Christian writer Tertullian condemned not only the philosophers but also the actors and wished them to hell. Isidore of Seville later explicitly warns against non-Christian poets and put actors, prostitutes, criminals and robbers on the same level. Classical literature was also full of allusions to non-Christian gods and heroes.

Among the verifiable losses in the Latin area, republican historical works, poetry of all kinds and especially tragedies are to be lamented. Books by dissident historians such as Cremutius Cordus were destroyed as early as the Roman Empire . The tenth book of the Institutio oratoria des Quintilian discusses numerous literary works towards the end of the 1st century AD, a considerable part of which is still preserved today, but much has also been lost. The predominantly fictional literature, which was particularly established at the time, is reviewed.

background

The period from 350 to 800 is the decisive one in the history of tradition. In the High Middle Ages it was believed that Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) had the great Palatine library in Rome burned. According to current research, it can be ruled out that Pope Gregory had the library destroyed, as the loss must have taken place before his pontificate. The Palatine Library , founded by Augustus and probably the largest in Rome, disappeared from history without any hint of its fate. This was the result of research since the 1950s, according to which it appeared certain that the loss had occurred before 500. With the completion of the CLA in the 1970s, this knowledge was further consolidated.

In the secular German research around 1900 (Germany was leading in the study of antiquity at the time) the destruction of ancient literature was one of the reasons for giving the Middle Ages the strongly derogatory term " Dark Ages ", which was coined during the Renaissance and Enlightenment stigmatize. It also became an argument in the anti-Catholic Kulturkampf at the end of the 19th century.

The reasons for the book losses remained controversial in the 19th century. On the one hand there was Protestant and secularly oriented historiography, to which anti-Catholic intentions were assumed if they attributed the book losses primarily to Christianization, on the other hand there was church history research, which was said to have apologetic interests if the book losses were more general Attributed to the decline of Roman culture. Based on the sources, there was no compelling research consensus.

The scientific discussion about the reasons for the fall of the Western Roman Empire has also been going on for over 200 years without a consensus in sight. While the barbarian invasions played an at least not insignificant role in the fall of the empire, archaeologists with a more cultural-scientific approach connect the end of antiquity with the extinction of its non-Christian tradition in the year 529. The loss of literature was particularly momentous.

The fall of Rome was seen by some contemporaries as apocalyptic . In the Old Testament, the Jewish state first had to get into dire straits before God sent his heavenly hosts to establish the kingdom of God on earth. According to the New Testament, too, a great catastrophe must first occur before Paradise on earth comes and the history of mankind is fulfilled. This is the prophecy in John's Apocalypse . Belief in the imminent catastrophic end of the world is evident in eschatology and millenarianism .

Even if the stories of the martyrs seem exaggerated, it is known that the Roman state allowed early Christianity to be systematically pursued in phases since Emperor Decius (247-251) . The Christians, for their part, later used these measures against the religions of the ancient world. An earlier example of the persecution of Christians can be found for most of the attacks by Christians.

Late antique “paganism” was a polytheistic variety of ancient religious communities. Greco-Roman cults were still widespread in the 3rd century, but were increasingly displaced even earlier by so-called “oriental” religions, including the cult of Mithras , Cybele and Isis , but also, for example, by syncretistic Manichaeism . There was also local folk beliefs . There was no competition among these religions, as anyone could participate in any number of cults. Especially when dealing with Christianity, intellectual followers of non-Christian religions were shaped by Hellenistic ideas.

Although examples of non-Christians and Christians living together without conflict can be found in the empire, the violence of religious wars has recently been emphasized again. Religious conflicts were often socially motivated and fueled by Christian institutional or spiritual authorities. Early Christianity was particularly attractive to the less literarily educated lower classes. The official religious policy depended on the respective ruling emperor, with Theodosius I and other emperors mainly only intervening in internal church disputes, but legitimizing religious battles through individual laws. The decline of the ancient religions was a long process. A work on the Christianization of the Roman Empire sums up: “Silencing, burning and destroying were manifestations of theological evidence. And as soon as this lesson was over, monks and bishops, as well as generals and emperors, drove their enemy from our sight. We cannot report on events that we can no longer understand. "

The book loss before 500

The ancient books were certainly no longer available in the East and West from 800 onwards. They were probably no longer available in the Latin West by around 550. While authors such as Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus and Boethius around 520 were still able to fall back on a wealth of works, the devastating Gothic War of Emperor Justinian brought a turning point for Italy , which ruined and partly exterminated the educated, wealthy Western Roman elite, which was previously the most important bearer of the ancient culture and the buyer of new copies of old texts.

Cassiodorus lived in Italy from around 490 to 583. He was a senator and initially magister officiorum of the Ostrogoth king Theodoric . During the Gothic War, after a stay in Constantinople around 540, he retired to his private lands in southern Italy and founded the Vivarium monastery . He spoke Latin, Greek and Gothic , collected and translated books from Greek into Latin. His stated goal was to save classical education, and he was the first to make copying of books compulsory for monks.

Due to his wealthy position and his extensive contacts, including in the Greek area, he was in an exceptionally good position to obtain the most important books still available in the Mediterranean region of his time. In his own texts he describes his library, individual books and quotes from works that are probably available to him. On the basis of this information, A. Franz and later RAB Mynors created “a preliminary overview of the inventory of the Vivarium library”. The result was that Cassiodorus did not know much more ancient texts than we do today. It had the only major library of the late sixth century, of which something is known about the contents. Based on the citations, she had about 100 codices - especially in comparison with Symmachus and Boethius, this shows how massive the cultural losses around 550 were. Cassiodor's library formed a bottleneck - what he was able to save was mostly preserved.

However, his library had a considerable influence on the tradition of the Latin West: “In Italy, a thin, intertwined layer of the old senatorial nobility, represented by the families of the Symmachi and Nicomachi, was able to preserve ancient authors as witnesses of former Roman greatness To do a task. A member of this group, Cassiodorus, initiated the transition from ancient book culture to the ethos of monastic writing. The Vivarium library he founded worked far beyond the Alps via the intermediate stations Rome and Bobbio. "

The situation was similar with Bishop Isidore of Seville , who lived in Spain from around 560 to 636. It had the only library of the 7th century that anything is known about its contents. Paul Lehmann undertook a corresponding examination of Isidore's writings. He concluded that Isidore was probably building on at least three books by Cassiodorus. Lehmann: "Most of the writings that Isidore gives with title and author, he has probably never read." Isidor has quoted 154 titles . His library was therefore probably much smaller than that of Cassiodorus.

The continued existence of large libraries is no longer proven after 475. Small monastery libraries may only have a volume of 20 books. As the factual standard work “History of the Libraries” stated in 1955, the loss must have occurred before 500: “The great loss of ancient texts had already occurred at the beginning of the 6th century, and the supply of writers Cassiodorus and Isidore had at hand , does not significantly exceed the circle of what we know. "

The Christian subscription

A subscription was a short post text describing when the book was copied and who checked it for accuracy. The only known pre-Christian example shows a clear effort to improve the text by naming several templates.

In the surviving stock of books, subscriptions from Christian times are the rule. This endeavor to correct philological corrections can no longer be recognized in part; Reynolds and Wilson, therefore, doubt that Christian subscription to classical literature was an essential aid. They see little evidence that the publication of non-Christian texts indicates any opposition to Christianity; It is rather unclear whether non-Christians were still involved at all at this time. The originators of subscriptions from the Nicomachi and Symmachi families were already Christians.

Reynolds and Wilson see the "sudden reappearance of subscriptions in secular texts towards the end of the fourth century" more connected with the transcription from the papyrus roll to the parchment codex. And as Michael von Albrecht writes: "Authors who are not taken into account here are henceforth eliminated from the tradition", or to put it another way: they "were thus finally at the mercy of the fate of chance survival on papyrus."

However, Reynolds and Wilson consider the largely high social status of the people mentioned in the Christian subscriptions to be historically interesting: “The predominantly high rank of the people appearing in the subscriptions suggests that it was their stately bookcases in which ours were Texts lay before they found their way into the monasteries and cathedrals, which ensured their survival. ” In this context, Alexander Demandt pays tribute to the merits of the aristocratic descendants of the non-Christian“ Symmachus ”circle in saving classical literature for the Latin West. It is also interesting that a text was apparently corrected centuries after it was copied.

The climax of the religious wars around 400

In the period from 300 to 800 there were repeated incidents in which individual libraries could have been destroyed, especially natural disasters. The last known library from antiquity is the Imperial Library of Constantinople , which was destroyed by fire around 475 with 120,000 codices. The next known library is only 100 years later that of Cassiodor with around 100 codices.

The period around 391 is often viewed as a high point in the religious struggle between Christianity and pagan beliefs. Most recently, however, Alan Cameron argued in a comprehensive study that in the late 4th century these contrasts were not always as sharply pronounced as often assumed. It is, for example, incorrect that the cultivation of classical education for Christians was allegedly of no greater importance and, on the other hand, convinced Pagane to pursue this as an expression of their religious convictions. A decisive boost in the Christianization of officials and educational institutions took place after the death of the last non-Christian emperor Julian Apostata , in the period between the 1960s and 1990s. The Senate in Rome was more and more "Christianized" in the course of the later 4th century, even if Pagans still represented a not insignificant group in it at least until the beginning of the 5th century.

The Mithras cult was one of the widespread rival religions of Christianity . Although the actual attractiveness of these religions has often been questioned by church historians, they were so widespread that Ernest Renan judged: "If Christianity had died of a fatal disease in the course of its spread, the world today would be a community of Mithras believers." Members of the imperial elite were often members of these "oriental" religious communities before they gradually converted. So even after his conversion in 312 , Constantine the Great († 337) had the sun god associated with Mithras publicly worshiped .

While Constantine the Great had only a few temples verifiably demolished, the Christian convert Firmicus Maternus recommended in his apologetic book " On the Error of Godless Cults " around 350 to the sons of Constantine the extermination of all ancient religions and the destruction of their temples. In 391, Emperor Theodosius I passed a law that all non-Christian temples should be closed. At the time, temples were most of the non-ecclesiastical cultural buildings, such as a library dedicated to the gods or the museum , a temple of the muse. In this context, Theodosius' edict was interpreted by some researchers as an attempt to destroy all non-Christian libraries as well. Modern historical research evaluates the emperor's legislation in a more differentiated way, obviously Theodosius I never ordered the destruction of the temple.

Under Honorius there was a decree in 399 to protect public works of art that were destroyed by Christians with the benevolent support of "authorities". A similar decree provided for the avoidance of violence in the destruction of rural sanctuaries. In 408, a nationwide law ordered the destruction of all non-Christian works of art that had remained until then ( iconoclasm ): “If any images are still in temples or shrines, and if today or ever before they received veneration from pagans anywhere, they should be torn down become."

The story of the Serapeum , which was the city library of Alexandria , is said to have been destroyed by Christians in 391 after non-Christians holed up in the building and murdered Christians in opposition to the implementation of the law. After 400 there is no trace of the Museum of Alexandria, which contained the famous great library and is occupied as a building up to around 380. In the 5th century the area is described as a wasteland. The important Christian Aristotle commentator Johannes Philoponos mentions the “great library” around 520, which was once the pride of Alexandria. During excavations in 2003 foundations were found.

An Asclepiades was one of the few non-Christian scholars in Alexandria around 490 . He and his circle believed they were the last priests of Osiris and used hieroglyphics in ritual acts. Haas assumes, however, that this circle could no longer read hieroglyphs. Because Asclepiades' son, Horapollon , wrote the only surviving late antique work on the meaning of hieroglyphs. However, there is no reference to their spoken language function. Only imaginative allegorical- mystical functions are described. Hieroglyphs were used until the 4th century, and there were certainly books about it at that time. Even a proven specialist does not seem to have had such a book around 500 in his private library in the scholarly center in Alexandria.

The Res gestae des Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330 to c. 395), the most important source for this period, mention the persecution and execution of apparently well-educated people who were accused of possessing books with prohibited content. Their codices and scrolls were publicly burned in large numbers. The books are said to have been "magic texts". Ammianus said, however, that they were mainly works of the " artes liberales ", the classical ancient sciences. As a result, according to Ammianus, in the "eastern provinces" "for fear of similar fates, the owners burned their entire libraries".

Ammianus also criticizes the superficial entertainment of the Roman upper class, adding: "The libraries were closed forever, like tombs." This was interpreted by most scholars in the 19th and most of the 20th centuries as if the great ones were Rome's public libraries have been closed. In recent times, some suspect that the statement could only have related to the house libraries and the amusements of the Roman nobility.

A little later, around 415, the Christian scholar Orosius visited Alexandria. He describes how he himself saw empty bookshelves in some of the temples there. These were "plundered by our own people in our time - this statement is certainly true." Also in Rome from 400 onwards the large libraries seem to have been closed or empty. Even assuming that the buildings of the Trajan's library were still standing in 455, there is no indication that they or others were still open there or still contained books.

Fall and change of the ancient city

Many cities in the west of the Roman Empire and especially in Gaul (but less so in the southern part) and Britain practically disappeared in the fifth century as a result of the invasions across the empire. For example, Trier , the seat of the Gallic prefecture until the beginning of the 5th century , has been plundered and pillaged several times. Local works, such as the Chronica Gallica , however, survived. The new Germanic rulers in the west tried to continue the ancient structures in other places (Spain, Italy, partly North Africa and South Gaul). Ammianus Marcellinus reports in his historical work that many Roman officers of Germanic origin were interested in classical culture and were often trained in it. Towards the end of the 5th century, the educated Gallo-Roman Sidonius Apollinaris praised the Germanic and Roman officer Arbogast the younger , who defended Trier against Germanic invaders, for his education.

In the individual areas of the empire, however, the ancient city was extensively restructured. In ancient times, the maintenance of public buildings, including public libraries, was largely based on volunteers, mostly wealthy citizens. As early as the third century there were complaints that more and more citizens were no longer willing to support individual institutions or no longer voluntarily took on certain offices. Obviously, the honors won didn’t seem to outweigh the burdens of public office. By the 6th century, the old structures had almost completely disappeared in many places. The cities now organized themselves more around the bishop as the main character.

An exemption from these financial burdens was offered in particular by joining the clergy . Constantine the Great tried to legally prohibit this emigration, but already at the city level he preferred the local Christian elite. In exchange for the expulsion of a non-Christian community or for proof of full conversion, the Christian emperors granted the cities privileges or status increases, with tax breaks playing a special role. This process probably reached its climax towards the end of the 4th century, with the result that urban elites could only retain their social status in non-Christian strongholds without baptism, especially since the practice of cult in public temples since Theodosius I was generally subject to the death penalty. In the private sphere, non-Christian cult activities could initially still be practiced largely without risk. In addition to spiritual interests, material interests are likely to have made the conversion to Christianity attractive to many noble families.

The epigraphic sources, which since the first millennium BC consistently testify to urban forms of entertainment, such as theater, music and sporting events, dry up during this time. The Greek grammar schools and other workplaces of non-Christian teachers and philosophers were given up, partly because the male nudity practiced there favored homosexuality in the eyes of Christians . The Christian author Theodoret wrote one of the last ancient writings against non-Christians (around 430), in which he explains that these events have been replaced by Christian alternative offers:

“Indeed, their temples have been so completely destroyed that one cannot even imagine their previous location, while the building materials are now dedicated to the shrines of the martyrs. […] See, instead of the feasts of Pandios, Diasus and Dionysius and your other feasts, the public events are now being celebrated in honor of Peter, Paul and Thomas! Instead of cultivating lewd customs, we now sing chaste hymns of praise. "

John Chrysostom also writes mockingly in an apologetic-polemical work:

“Therefore, although this diabolical farce has not yet been completely erased from the earth, what has already happened is sufficient to convince you of the future. The greater part has been destroyed in a very short time. From now on nobody will want to argue about the remains. "

The Notitia Dignitatum , a catalog of the official administrative posts in the Roman Empire around 400, gives no indication that anyone was still responsible for libraries. From other documents and grave inscriptions, however, we know that responsibility for one or more libraries was considered an important and honorable office before 30000. If the large libraries had still existed after 400, their management would have been of paramount importance. Because the administrator would have determined which books were still allowed to be available after Christianization and which were not.

Destruction of magic books

Ancient literature was also distributed in small and very small private libraries (such as the Villa dei Papiri ). The loss of the large public libraries could therefore probably not even affect half of the holdings. The complete loss of the millions of books written about 350 ago must have been a lengthy process. Apart from the descriptions of book persecution by Ammian and John Chrysostom , it is known that so-called "magic books" were persecuted. This literary genre was rather rare at the beginning of the first millennium (at most 0.3% in Oxyrhynchos ). Since the official recognition of Christianity in the 4th century, it has been the target of persecution much more frequently. Since Ammian reports on the burning of books of the classical sciences in the context of the persecution of magic books, it is possible that other non-Christian literature was also destroyed in this context.

An extensive work by Wilhelm Speyer in 1981 was devoted to the topic of ancient book destruction. Regarding the aspect "The destruction of pagan literature", Speyer found references to the destruction of anti-Christian writings, of pagan ritual books, of lascivious literature as well as magic books. In Speyer's view, writings from classical literature and science were never deliberately destroyed. Persecution of magic scriptures , probably curse - and harmful spells / rituals, already existed in non-Christian times. Educated people, like Pliny the Elder , thought magic was simply a fraud. In popular belief, however , magic was always more or less present.

The only way to find out whether a book contained magic or science was by reading the book. Even then, it still took some education to tell the difference in every case, and not every Christian involved in book destruction should have been adequately educated. A non-Christian book could be recognized as a magic book if it was dedicated to a famous non-Christian or a deity, or if it only quoted a scientist who was now regarded as a magician. The charge of magic was very broad and was also used against ancient religions in general.

According to Speyer, the burning of magic books by Christians goes back to a passage in the book of Acts . It tells how Paul cast out demons to heal the sick. He was more successful in this than the "sons of a Jewish high priest Skeva", who are referred to as the "wandering Jewish conjurers". After Paul's triumph in the city : “But many of those who believed came and confessed and proclaimed their deeds. But many of those who had practiced cheeky arts brought the books together and burned them before everyone; and they calculated its value, and found it to be fifty thousand pieces of silver ”(Acts 19: 18-19). In this passage one can only assume from the context that books with spells are meant. The large number of books destroyed here makes it unlikely that they were just magic books in the modern sense.

Apart from this biblical passage, there is only evidence of the burning of so-called magic books in the context of Christian conversion from the 4th century onwards. From around 350 until the Middle Ages, there are descriptions that magic books were visited and destroyed. Between 350 and 400 owners of such magic books could also be punished with death:

“During this time, the owners of magic books were dealt with with the greatest severity. From John Chrysostom we learn that soldiers searched his hometown Antioch on the Orontes for magical writings. When he was walking along the Orontes with his friend at that time, they saw an object floating on the river. They pulled it out and realized they were holding a forbidden spellbook. At the same moment soldiers appeared nearby. But they still managed to hide the book unnoticed in their clothes and a little later to throw it back into the river. So they escaped the danger to life. As Chrysostom further reports, an owner of a magic book had thrown it into the river for fear of the persecutors. He was watched, convicted of sorcery and punished with death. "

In addition to Ammianus, there are other sources according to which house searches were carried out at that time to find non-Christian books. About 100 years later (487 to 492) there is another report of house searches. Students in Beirut found books on magic from a “John with the surname 'Walker' from Thebes in Egypt”. After he burned them, he was forced to give out the names of other owners. Thereupon the students began "supported by the bishop and the secular authorities", a major search operation. They found such books on other students and some notable people and burned them in front of the church.

In an imperial law since 409 “mathematicians” were obliged “to burn their books in front of the bishops, otherwise they would have to be driven out of Rome and all parishes.” Usually mathematicians were equated with astrologers in late antiquity , but in antiquity they could Mathematics also includes essential parts of the classical sciences. Astrologers (astrologers) were only understood to mean astrologers in simple language.

In 529, Emperor Justinian closed the Academy of Athens. In 546 he announced a teaching ban for non-Christians and ordered the persecution of non-Christian “ grammarians , rhetors , doctors and lawyers” and in 562 the public burning of “pagan books”. These books may have been confiscated in the course of the persecution. A more recent article on book destruction in the Roman Empire summarizes:

“Book burning became a prominent manifestation of religious violence in the late ancient Roman Empire. Religiously legitimized violence in late antiquity, for which the burning of a forbidden book is only one example, were understood as acts that fundamentally satisfied God and therefore brought spiritual benefit to those practicing. Since book burning satisfied God, it was frequently performed, by persons acting as representatives of Christianity and in the vicinity of churches. In doing so, bishops, monks, and even religious laypeople adapted an ancient ritual that has always served the dual purpose of annihilation and purification to suit their needs. [...] The abundance of such incidents during this period reveals a gradual process of transformation. "

Education and lore

The ancient world likely had a relatively high level of literacy. Pliny wrote his encyclopedia specifically for peasants. Papyrus finds from Egypt confirm that apparently poor farmers in the provinces were also able to read and write. A tombstone found in Bavaria and erected by a slave for a fellow slave even points to literacy among rural slaves in the provinces. This has been documented for a long time for urban slaves.

As early as the late 4th century, non-Christians were increasingly being pushed back from the educational establishment. Emperor Julian tried in 362 with the edict of rhetoric to effectively exclude Christians from teaching. This state intervention later struck back on the non-Christians.

Western Roman Empire

The loss of ancient papyri and public access to literature had a direct impact on the level of education of the entire population in the Western Roman Empire. At the end of this process, the written form largely disappears and the historical information is more than incomplete. With regard to tradition, Herbert Hunger assessed this period: "Worse [than the Germanization] for Roman culture is the final victory of Christianity."

The preservation of non-Christian traditions concentrated on the disempowered senate aristocracy, for example the members of the so-called Symmachus group . Alexander Demandt writes: "A large part of Latin literature has been saved by members or employees of these Senate families."

At the beginning of the sixth century, the learned Boëthius worked at the court of Theodoric in Ostrogothic Italy . He translated and commented on the works of Aristotle and the Isagogue of Porphyry and was the first Christian to write textbooks on artes . Since he was accused of treason and executed, he was unable to complete his great project of making the main works of Plato and Aristotle accessible through translations for the Latin West. After all, his translations remained the only writings of Aristotle available in the Latin-speaking world until the 12th century. Since knowledge of Greek has hardly been available anywhere in the West since the early Middle Ages, it is thanks to him that part of ancient Greek philosophy was preserved in the Latin Middle Ages .

The Christian Attitude to Pagan Literature

The attitude of Christians to non-Christian literature changed over time. The fearful dream of Hieronymus (347-420), in which the young scholar turns away from his beloved secular books , is often quoted . Although canon law forbade clerics to read pagan literature, pagan literature was still known to clergy at least in the 4th century, insofar as it was part of rhetoric lessons opposed by Christianity; in the 6th century, Latin pagan texts are no longer part of the training.

The church father Augustine (354–430) argued for the preservation of non-Christian literature, but in principle only wanted to see it kept locked in a library; it should not be spread or taught. He spoke out against the teaching of the ars grammatica and everything that goes with it. Only church scriptures are to be used.

Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) took a clearly negative attitude towards ancient education. He avoided classic quotations and did not tolerate them in his environment. In addition, he forbade the bishops by law to teach grammar and also personally reprimanded this, whereby the fear of profaning sacred texts may have played a role.

Also Isidore of Seville warned that it should be permitted only very consolidated students to read non-Christian writings in his rules for monasticism. “After Cassiodorus,” says Manitius, “you feel as if you have been transported into another world: mysticism, superstition and miraculousness are now overgrowing what used to be a logical and appropriate presentation” ”.

As a result of this cultural policy, the clergy could not maintain the literacy level either. Cassiodorus wrote a textbook on ancient grammar. EA Lowe said: "From the rules of orthography and grammar that he laid down, one can judge how deep scholarship had already sunk in his day." For the Latin West, "the 6th century is the darkest phase in cultural decline." this time when the copying of classical texts decreased so much that it came dangerously close to a break in the continuity of pagan culture. The dark centuries irretrievably threatened the transmission of classical texts. "

The letters of Boniface , in which he lamented the educational need of the clergy in his time, also point to the decline, which according to Laudage and others goes back to the 5th century. In Isidore's time, a law was passed that excluded illiterate people from the office of bishop - the highest office the Church had at the time. According to the letters of Alcuin , who tried to raise the level of education in the Carolingian Empire, this law was hardly successful.

The monastic tradition

Quite a few monastery inmates of the Middle Ages were illiterate, at least on the continent. Even some writers of codices only painted the textual image of the template. But this also had the advantage that the copies of this period are very true to the original - no one dared to “improve” the original. It is mainly thanks to the copying activity of the monks that the remaining part of ancient literature was preserved, which has now been handed down on the more noble parchment . Since this writing material has been cultivated to the best of our ability since the early Middle Ages , we are still in approximately possession of the texts that were available to Cassiodorus: “The extremely poor tradition of classical culture in these dark centuries then gives the Carolingian Renaissance special significance, in who, on the basis of ancient codices that survived the collapse of the Roman Empire, in turn come to light ancient authors who would probably have been condemned to damnatio memoriae by the dark centuries . "

“It is one of the most astonishing paradoxes in world history that the church and monasticism, which once so bitterly and fundamentally fought against the permissive, erotic literature of pagan antiquity out of deep religious conviction, became the most important transmitters of texts of this kind. Was it the lively aesthetic charm of the same that made it possible to survive in monastery libraries, or was it the now more free spirit of the Middle Ages towards a bygone cultural tradition that no longer had to fight victorious Christianity as threatening? In any case, there was an almost joyful takeover of the very worldly, ancient heritage, which one had once tried to erase as a diabolical counterworld. "

Going back from the 16th and 17th centuries, the beginning of the late Middle Ages (around 1250) shows a literacy rate in continental Europe of around 1%. Roughly estimated this means: The 90% rural population were illiterate, of the 10% urban population it was only 10% who could read and write. However, the regional differences could be considerable: In Scandinavia this was the saga time with a very high level of literacy. From 700 to 1500, however, the Middle Ages showed signs of a steady increase in written form. In the 6th and 7th centuries, the spread of writing in the West must have been very low.

Ancient education in the Eastern Roman and Byzantine Empires

In the Greek East of the Roman Empire, the lines of tradition, especially compared to the Latin West, showed far fewer breaks, both in terms of tradition and in terms of the educational tradition. An educated elite continued to exist here, at least up to around 600, who looked after the traditional literature. It should be noted that up to the late 6th century, even in the Eastern Roman upper class, in addition to Greek texts, Latin works were also read and handed down. Not only did authors like Jordanes and Gorippus still write Latin works in the classical tradition around 550, but texts by authors like Cicero and Sallust were also copied. It was not until after 600 that knowledge of the Latin language and literature ceased in the East.

By Paideia , the classical form of education, it differed from the barbarians and the ordinary citizens and was proud certainly as a Christian. In 529 (531?) The Platonic Academy in Athens was closed by Justinian I , but other originally non-Christian educational centers such as Alexandria continued to exist. However, these lost in the 6./7. Century in importance and were partly abruptly closed. In Alexandria, arguably the most important center of ancient education, in contrast to Athens, there was a substantial balance between classical tradition and Christianity in the works of Christian authors such as Johannes Philoponos and Stephanos of Alexandria, as well as in the great epic of Nonnos of Panopolis . The university there only perished after 600 as a result of the Persian invasion and the subsequent Arab conquest.

In the east, too, there were breaks and crises in which book collections were likely to have been lost; in particular, the great Persian War (603–628 / 29) and the subsequent Islamic expansion represented the first significant turning point in the 7th century . However, this was not as radical as that which had affected the Latin education of the West in the 6th century.

Because the cultural continuity that existed in Byzantium was the reason why (Greek) classical literature continued to be received here after the end of antiquity in the 7th century and after the turmoil of the early Middle Byzantine period. After the Christian iconoclasm in Byzantium (8th and, according to recent research, especially early 9th century) there are only seldom reliable indications of a clear rejection of classical literature by Byzantine authors. So the monk Maximus Planudes from his created in 1301 Edition of the Greek Anthology such epigrams deleted, which seemed to him offensive. But this censorship remained an exception.

In the Byzantine Empire , authors who were involved in the transfer from Rolle to Codex from the 3rd / 4th They were not taken into account in the 19th century, at least still surviving in excerpts in compilations and secondary references . Probably at the beginning of the 11th century, the Suda was created there , a lexicon with references to numerous works that have been lost today. The authors of the Suda probably for the most part made use of the above-mentioned secondary references, especially lexicons compiled earlier.

In the 9th century, on the other hand , the Patriarch Photios apparently still had some ancient and late ancient Greek texts in their entirety, which today are completely or largely lost; including works by Ktesias , Diodor , Dionysius of Halicarnassus , Arrian , Cassius Dio , Dexippus , Priskos , Malchus of Philadelphia and Candidus (some of whom were already Christians). He read these with friends, making no distinction between pagan and Christian authors. In the 10th century, Emperor Constantine VII had (mainly Byzantine) historians evaluated and summarized, some of which are now lost, and in the 12th century the historian Zonaras also used older Byzantine historical sources for his epitoms , the content of which is only known through his summaries is. In Constantinople in particular , there must have been libraries in which Byzantine works that were lost in the High Middle Ages were kept today.

The reason for the break with older literature in the Byzantine Middle Ages is assumed to be the declining importance of Paideia from the late 11th century, but above all the military and social turmoil that shaped the late Byzantine period. Nevertheless, after the collapse of Byzantium in the 15th century , Byzantine scholars like Plethon were able to convey a nucleus of ancient Greek education and literature to the West that had survived the Middle Ages there.

Arabic tradition

The Islamic expansion of the 7th century brought large parts of the Eastern Roman Empire under Islamic rule. In the regions of Palestine and Syria , unlike in the Latin West, a relative cultural continuity was observed: “Since the invaders were very interested in Greek education, many texts were translated into the new national languages and structures and libraries continued to exist that could guarantee a higher education. ”Individual works and compilations of works by Arabic translators and editors are known as early as the 7th century. Christian-Syrian scholars played an important mediating role, their occupation with Greek science and philosophy going back to early late antiquity. Syria was a hotspot for heretics , especially for monophysitism , who were persecuted by the Catholic Church and banished there.

As early as the 3rd century, the Persian Academy of Gundischapur had collected ancient scientific writings in the then Sassanid Empire , which were also accessible to scholars who wrote in Arabic. Hārūn ar-Raschīd called Yuhanna ibn Masawaih to Baghdad, who had studied in Gundischapur with Gabriel ibn Bochtischu . For his “ House of Wisdom ” in Baghdad, ar-Rashid's son, Caliph al-Ma'mūn, requested ancient writings from the Byzantine emperor Theophilos in the 9th century , which were translated into Arabic in large numbers in Baghdad. Important translators such as Hunain ibn Ishāq , the head of the translator group in Baghdad and a disciple of ibn Masawaih, were Christians and familiar with ancient culture. In addition to the medical textbooks of Hippocrates and Galenos , philosophical writings by Pythagoras of Samos, Akron of Agrigento, Democritus , Polybos, Diogenes of Apollonia , Plato , Aristotle , Mnesitheos of Athens , Xenocrates , Pedanios Dioscurides , Soranos of Ephesus , Archigenes, Antyllos , Rufus were published Translated directly from the Greek by Ephesus , other works such as those of Erasistratos were known to the Arab scholars through Latin quotations from Galen's works. More recently, book destruction during late antiquity has also been associated with the foundations of Christianity in the Arab world. The scientific advances in Christian Europe in the 10th and 11th centuries are due not least to Arab knowledge.

Return to Europe

The Arabic translations by ancient Greek scholars known as " Graeco-Arabica " came back to Europe as translations from Arabic from the 11th century. In Monte Cassino , Constantine the African translated works of Islamic medicine from Arabic into Latin.

Sicily had belonged to the Byzantine Empire until 878 , was under Islamic rule from 878-1060 as an emirate of Sicily, and between 1060 and 1090 under Norman rule. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily remained trilingual, so translators who knew the language were found here, especially since contact with the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire was maintained. In Sicily, translations were usually carried out directly from Greek into Latin, only when no suitable Greek texts were available, Arabic scripts were used.

With the Reconquista , the reconquest of al-Andalus , which had been largely under Arab rule since the 8th century and in which Jewish scholarship had also experienced a " golden age ", the great epoch of the Latin translation of ancient authors began. After the conquest of the Spanish city of Toledo in 1085 taught Raymond of Toledo in the Cathedral Library of the city , the Toledo School of Translators one. One of the most prolific translators from Toledo was Gerhard von Cremona .

Search in Europe

The search of Italian scholars like Poggio Bracciolini for ancient writings ushered in the Renaissance in Europe from the 14th century . In 1418, Poggio discovered a preserved copy of “ De rerum natura ” by Lucretius in an unknown German monastery . Original Roman papyri ( Epicurus , Philodemos of Gadara ) were found in the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum in the 18th century . The deciphering of the charred and extremely difficult to unroll Herculanean papyri is still going on. The transcription of palimpsests became possible from 1819 due to the work of Angelo Mais . Among other works, Cicero's De re publica has been recovered from a palimpsest preserved in the Vatican Library .

literature

Monographs

- Mostafa El-Abbadi: Life and Fate of the Ancient Library of Alexandria. 2nd Edition. Unesco, Paris 1992, ISBN 92-3-102632-1 .

- Hans Gerstinger: Inventory and tradition of the literary works of Greco-Roman antiquity . Kienreich, Graz 1948.

- Michael H. Harris: A history of libraries in the western world . Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Maryland 1995, ISBN 0-8108-3724-2 .

- Wolfram Hoepfner (ed.): Ancient libraries . Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2846-X .

- Herbert Hunger among other things: The text transmission of ancient literature and the Bible . dtv, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-423-04485-3 (edition of the history of the textual tradition of ancient and medieval literature , volume 1, Atlantis, Hersching 1961).

- Elmer D. Johnson: A history of libraries in the western world . Scarecrow Press, Metuchen, New Jersey 1965, ISBN 0-8108-0949-4 .

- William A. Johnson: The literary papyrus roll. Format and conventions; an analysis of the evidence from Oxyrhynchus . Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut 1992.

- Manfred Landfester (Hrsg.): History of the ancient texts. Lexicon of authors and works (= Der Neue Pauly. Supplements. Volume 2). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2007, ISBN 978-3-476-02030-7 .

- Edward A. Parsons: The Alexandrian Library. Glory of the hellenic world. Its rise, antiquities, and destructions . Elsevier, New York 1967.

- Egert Pöhlmann : Introduction to the history of transmission and the textual criticism of ancient literature. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1994.

- Lucien X. Polastron: Livres en feu: histoire de la destruction sans fin des bibliothèques. Paris, Gallimard, 2009, ISBN 978-2-07-039921-5 .

- Wayne A. Wiegand (Ed.): Encyclopedia of library history . Garland, New York 1994, ISBN 0-8240-5787-2 .

- Leighton D. Reynolds, Nigel G. Wilson : Scribes and scholars. A guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature. 3. Edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1992, ISBN 0-19-872145-5 .

- Colin H. Roberts, Theodore C. Skeat: The birth of the codex . Oxford University Press, London 1989, ISBN 0-19-726061-6 .

- Dirk Rohmann : Christianity, Book-Burning and Censorship in Late Antiquity. Studies in Text Transmission (= work on church history . Volume 135). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-048445-8 ( review H-Soz-u-Kult / review sehepunkte ).

- Eberhard Sauer: The archeology of religious hatred in the Roman and early medieval world . Tempus Books, Stroud 2003, ISBN 0-7524-2530-7 .

- Wolfgang Speyer: Book destruction and censorship of the spirit among pagans, Jews and Christians (= library of books. Volume 7). Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-7772-8146-8 .

- Edward J. Watts: City and school in Late antique Athens and Alexandria . University of California Press, Berkeley, California 2006, ISBN 0-520-24421-4 .

Essays and lexicon articles

- William EA Axon: On the Extent of Ancient Libraries. In: Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom. Series 2, Volume 10, 1874, pp. 383-405, ( digitized ).

- Robert Barnes: Cloistered Bookworms in the Chicken-Coop of the Muses. The Ancient Library of Alexandria. In: Roy MacLeod (Ed.): The Library of Alexandria. Center of Learning in the Ancient World. Tauris, London et al. 2000, ISBN 1-86064-428-7 , pp. 61-77.

- Karl Christ , Anton Kern : The Middle Ages. In: Georg Leyh (Ed.): Handbuch der Bibliothekswissenschaft. Volume 3, Half 1: History of Libraries. 2nd, increased and improved edition. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1955, pp. 243-498.

- Dieter Hagedorn : Papyrology. In: Heinz-Günther Nesselrath (Ed.): Introduction to Greek Philology. Teubner, Stuttgart et al. 1997, ISBN 3-519-07435-4 , pp. 59-71.

- George W. Houston : A Revisionary Note on Ammianus Marcellinus 14.6.18: When did the Public Libraries of Ancient Rome close? In: The Library Quarterly. Vol. 58, No. 3, 1988, pp. 258-264, JSTOR 4308259 .

- Robert A. Kaster: History of Philology in Rome. In: Fritz Graf (ed.): Introduction to Latin Philology. Teubner, Stuttgart et al. 1997, ISBN 3-519-07434-6 , pp. 3-16.

- Wolfgang Speyer : Book destruction. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Supplement volume 2, delivery 10. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-7772-0243-6 , Sp. 171-233 = Yearbook for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 13, 1970, pp. 123-151.

- John O. Ward: Alexandria and its medieval legacy. The book, the monk and the rose. In: Roy MacLeod (Ed.): The Library of Alexandria. Center of Learning in the Ancient World. Tauris, London et al. 2000, ISBN 1-86064-428-7 , pp. 163-179.

Web links

- Friedrich Prinz: The spiritual beginnings of Europe . In: Zeit online , June 12, 2002.

- H. Rösch: Lecture manuscript on library history , Cologne University of Applied Sciences (PDF; 880 kB; status May 2005, copy in the Internet Archive)

- The disappearance of ancient books . Livius.org (English)

Remarks

- ↑ Gerstinger (1948).

- ↑ Although much Greek literature has been preserved, the amount actually brought down to modern times is probably less than 10% of all that was written “Although a lot of Greek literature has been handed down, the proportion of what has actually been preserved into modern times remained less than 10% of what was written. ”(Johnson 1965). The same book received a significant change in this passage from a new author 30 years later: Why do we know so little about Greek libraries when such a relatively large amount of classic Greek literature has been preserved? It is estimated that perhaps ten percent of the major Greek classical writings have survived. “Why do we know so little about the Greek libraries when such a relatively large stock of classical Greek literature has survived? It is estimated that almost 10% of the larger Classical Greek scripts survived ”(Harris, 1995, p. 51).

- ↑ So the surviving inventory numbers from the death of the headmaster of the library Callimachos (approx. 240–235 BC according to Parsons) up to Caesar's visit to Parsons (1952).

- ↑ Most of the library holdings consisted of individual copies. Through the travels of the first book source, Demetrios von Phaleron, came to about 280 BC. 200,000 rolls together ( Flavius Josephus , Jüdische Altert becoming XII, 2,1). Until the death of Callimachus approx. 235 BC. Then there were 490,000 (Tzetzes at Parsons). These were also procured by different peoples. If one had only wanted to multiply the inventory through copies, this procurement through travel would hardly have been necessary. One could have copied a basic stock as often as desired in Alexandria, since there was enough papyrus on site. Further sources on this can be found in Parsons (1952).

- ↑ Parsons (1952) estimates over a million. Little Pauly estimates under the keyword Alexandria 900,000 without explanation. A decline is possible during the so-called "3rd century crisis".

- ↑ The volume of Latin texts preserved today is around a third of the size of Greek texts. It is unclear whether this is due to the far poorer tradition of the Latin West in the early Middle Ages or whether title production was actually lower. This is likely to have been the case at least for the Roman Republic in comparison to the Greek and Hellenistic poleis.

- ↑ For the early imperial period it can be assumed that it was an honor for authors to be represented in the large libraries. In exile, Ovid , who had fallen out of favor, complained that his writings had been rejected by the keeper of the (Palatine) library. (Ovid, Tristia 3,1,59 ff.).

- ↑ Among the literary papyri in a garbage dump in Oxyrhynchos about 20% were texts by Homer . Extrapolated to the Greek part of the empire around 200, this indicates millions of copies in circulation. The big libraries did not take every title (Ovid, Tristia 3,1,59 ff.). A title that made it into the Alexandria library is likely to have existed in numerous copies across the empire. The libraries of many of their books were obtained from publishers with whom they had subscription contracts. There were two neighborhoods in Rome that were known as locations for publishers and booksellers. Extensive book trade is also attested in some provincial towns. From Horace , Carmina 2,20,13 ff. And Martial 7,88; 11.3, it is claimed that their works were spread to the border regions of the empire; for Varro this is confirmed by Pliny the Elder (Pliny, Naturalis historia 35.11). Around 100 AD in Rome, the initial print run for a private commemorative publication of 1,000 copies is documented (Pliny, Epistulae 4,7,2), which indicates a considerable production capacity. See Julian Krüger: Oxyrhynchos in the Imperial Era . Frankfurt a. M. 1990, Horst Blanck: The book in antiquity . Munich 1992.

- ↑ List of preserved manuscripts last from Manfred Landfester: History of ancient texts. Work dictionary . The New Pauly, Supplements 2 (2007).

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus 14,9,2; John Zonaras 14.2; for dating, see for example Viola Heutger: Did the library in Constantinople make a contribution to the Codex Theodosianus? In: Harry Dondorp, Martin Schermaier , Boudewijn Sirks (eds.): De rebus divinis et humanis: Essays in honor of Jan Hallebeek. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht unipress, Göttingen 2019, pp. 179–192, on dating (around the year 475) p. 185 with note 34; Heinrich Schlange-Schöningen : Empire and education in late antique Constantinople (= Historia individual writings. Issue 94). Steiner, Stuttgart 1995, p. 106: in the year 475; Alexander Demandt : The late antiquity. Roman history from Diocletian to Justinian. 284–565 AD 2nd completely revised and expanded edition. Beck, Munich 2007, p. 445: in the year 476; Horst Blanck : The book in antiquity. Beck, Munich 1992, p. 177, names the year 473 without any further explanation.

- ↑ On the palace library of Constantinople see Pöhlmann (1994). The estimate of 100 for Cassiodor is based on the list of titles by Franz and Mynors (see below) and about 4 titles per codex, which was more typical around 800. Most of the codices in the 5th century were much larger than around 800.

- ↑ A roll with 83,300 characters requires around 23 hours of writing time at 1 character per second. Together with the production of the papyrus roll and some drawings, this can be done within 4 working days. With 400 people ( Alexandria had over 300,000 inhabitants according to Diodorus (17, 52), with the unfree it could have been over 1 million [ Der Neue Pauly Vol. I, Sp. 464]) an order of 40,000 rolls would then be within 400 Days to do.

- ↑ Book editions from Alexandria were considered to be of particularly high quality and evidently represented a commercial product. Under Emperor Domitian (81–96) the loss of a public library in Rome could be compensated for with a delivery from Alexandria. (Pöhlmann, 1994).

- ↑ Tzetzes , Prolegomena de comoedia Aristophanis 2,10.

- ↑ For references, see the description of the library statistics shown above .

- ↑ Seneca the Elder Ä., Controversiae 10, praef. 8th

- ^ For example, Pöhlmann (1994).

-

↑ The authors mention several ancient writings that have been lost today, which were still cited around 600 and conclude from this: “ The bulk of Latin literature was still extant ” (p. 81, German: “The majority of Latin literature was still available”). The existence of a few older books also does not indicate the continued existence of the majority of the ancient holdings. The fact that the libraries of Cassiodor and Isidore comprised around 90% of the ancient works known to us today shows that the decisive selection process at 1: 1000 should have already taken place before. Reynolds and Wilson (1991) only advocate the paraphrase / rotting thesis without discussing possible alternative views. They doubt the spread of the Codex as early as the 1st century and consider the Codex editions of the classics mentioned by Martial to be an unsuccessful attempt. Although the archaeological find of parts of a parchment codex from Martial's time ( De Bellis Macedonicis , P. Lit. Lond. 121, by an unknown author in Latin around AD 100) indicates an early distribution - even if the significantly more expensive codex was certainly less numerous than the role.

The claim that the Codex “ may have cost rather less to produce ” (p. 35, German: “should have been cheaper to produce than the papyrus roll”) is not substantiated. Papyrus pages can be glued to rolls of any length using the adhesive obtained from papyrus itself. As the findings of Oxyrhynchus show, this was even part of the ancient office work. The work of creating a codex with wooden covers is considerably more extensive. The production of a parchment page from sheep skin requires many tedious work steps and a multiple in technical effort and working time compared to a papyrus page. With reference to Galen (see below) it is claimed that a papyrus roll can live up to 300 years (p. 34). But Galen only mentioned the study of a possibly 300-year-old scroll to demonstrate the care of his text edition. He didn't mention the age of the papyrus as anything special. Therefore, an achievable minimum age for roles can be inferred from his quote. The assumption that the average service life of the rollers is shorter has not been proven. - ↑ Der Neue Pauly 15/3, sv Tradition, 2003, for example, names the reasons for the loss of books: "Victory of Christianity, decline of material culture and pagan education, transition from role to codex" (Col. 725) and "For the The continued tradition of pagan Greek literature was the establishment and official recognition of the Christian religion. "(Col. 713)" The copies of the classics were neither publicly 'institutionalized' [...] nor were pagan texts in the interest of the copyists from the monastery area. "(Ibid.)

- ↑ The durability of both under normal condition is not open to doubt. Many instances of long life of writings on papyrus could be quoted, but this is no longer necessary, since the myth that papyrus is not a durable material has at last been authoritatively and, one would hope, finally refuted by Lewis (Naphtali Lewis: Papyrus of Classical Antiquity, Oxford 1974.) From: Roberts and Skeat (1983), pp. 6f. The results published here and elsewhere can be traced back to the CLA investigations .

- ↑ C. Mango, in: Ders. (Ed.): The Oxford History of Byzantium . Oxford University Press 2002, p. 217: "Papyrus, produced uniquely in Egypt, was relatively cheap and durable".

- ^ BP Powell: Homer . 2nd edition, Oxford 2007, p. 11: "papyrus, an astonishingly durable and transportable material".

- ↑ With the exception of about 10 codices (the dating of which varies by up to 80 years), all the codices that exist today (in fragments) are from the period after 400. The "reproduction" of text and images made this dating possible. The statement that the archetypes of our tradition (east and west) arose around 400 goes back to Alphonse Dain : Les manuscrits . Paris 1949, back. Doubts about it with Karl Büchner , in: Herbert Hunger: History of the text transmission of ancient and medieval literature . 1. Ancient and medieval books and writings. Zurich 1961. When Karl Büchner was working on Hunger's Compendium of Greek and Latin Tradition around 1960, he saw much more open lines of tradition in Latin than in Greek (Hunger, 1961, p. 374). The statement made by Dain especially for the Greek East could also be confirmed for the West on the basis of the CLA.

- ↑ Julian Krüger: Oxyrhynchos in the imperial era . Frankfurt a. M. 1990.

- ↑ This value applies to the Latin area based on the CLA. The CLA show an average rate of surviving manuscripts of 1 to 2 per year for 400 to 700. An average production rate of 10 books per year for the Latin West results from a stochastically calculated loss factor from 5 to 10. For the rate of loss, which is particularly based on the linear development of the traditional manuscripts in Italy, see the article CLA .

- ↑ This term is used by Lorena de Faveri, sv . Tradition . In: Der Neue Pauly , 15,3 (2003), col. 710.

- ↑ Pornographic images or statues were far more common than most collections today show. Much material was locked away in special collections or even hidden again at the place of discovery in the 19th century. Pornographic writings also probably made up a significantly larger proportion in antiquity than in tradition.

- ↑ Sauer (2003), p. 14. Tertullian: De spectaculis , 30.

- ↑ Christ and Kern (1955), p. 306.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Diesner : Isidore of Seville and Visigoth Spain . Berlin 1977, p. 38. Ilona Opelt dealt with the topic of Christian apologetic swear words in her very detailed habilitation thesis. (Ilona Opelt: The polemics in Christian Latin literature from Tertullian to Augustin . Heidelberg 1980).

- ^ So John of Salisbury (1120–1180) in Policraticus ( De nugis curialium et vestigiis philosophorum , 1. ii. C. 26).

- ↑ Cassiodor's library inventory was reconstructed as early as 1937 (see below), that of Isidor's library by a French author in the 1950s.

- ↑ These end-time expectations can be found more clearly in the writings of Qumran than in the Old Testament. It is likely that these scriptures represent first-century thought in Judea rather than the Old Testament. According to Eisenman's interpretation, which became known in the 1990s, these end-time thoughts could have been a motivation for the Jewish uprising against Rome. One might even want to provoke the downfall of the state so that the prophecy could come true.

- ^ WHC Frend: Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church . Oxford 1965; Glen Bowersock : Martyrdom and Rome . Cambridge 1998.

- ↑ Speyer (1981) in particular points to these parallels.

- ↑ G. Alföldy: The crisis of the Roman Empire and the religion of Rome . In: W. Eck (Ed.): Religion and Society in the Roman Empire . Cologne 1989, pp. 53-102.

- ↑ See M. Beard, J. North, S. Price (Ed.): Religions of Rome . 2 vols., Cambridge 1998. F. Trombley: Hellenic Religion and Christianization . 2 vols., Leiden 1993/4.

- ↑ Michael Gaddis: There Is No Crime for Those Who Have Christ. Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire (Transformation of the Classical Heritage). Berkeley, CA 2006. the circumstances of the time in the 4th century cf. about Arnaldo Momigliano (ed.): The Conflict Between Paganism and Christianity in the Fourth Century . Oxford 1963.

- ↑ On the social stratification of early Christianity most detailed P. Lampe: Die Stadttrömischen Christisten in the first two centuries . Tübingen, 2nd edition 1989.

- ↑ The extent of conversions in the aristocracy was last compiled by M. Salzman on the basis of the literary findings: Michele R. Salzman: The Making Of A Christian Aristocracy. Social And Religious Change In The Western Roman Empire . Cambridge, MA 2002.

- ^ Ramsay MacMullen : Christianizing the Roman Empire AD 100-400 . New Haven: Yale UP 1984, p. 119.

- ↑ Kaster (1997), p. 15.

- ↑ Christ and Kern on Cassiodor's library: “In tireless collecting and searching, supported by the copying of his monks, he united them. The codices had come from all over Italy, from Africa and the most varied of countries; Cassiodor's rich means, the reputation of his name made it possible to acquire them. ”Christ and Kern (1955), p. 287.

- ^ RAB Mynors: Cassiodori Senatoris Institutiones . Oxford 1937: "a provisional indication of the contents of the library at Vivarium".

- ↑ Paul Klopsch, sv Tradition, Der Neue Pauly 15,3 (2003), Col. 721.

- ↑ Paul Lehmann: Research of the Middle Ages, Selected Treatises and Essays , Vol. II, Stuttgart 1959.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Library History (1994).

- ↑ "The more important libraries of antiquity disappeared around AD 600, and early monastery libraries could have comprised around 20 books." Ward (2000) believes that he can prove the loss before 500 without reference to Cassiodorus.

- ↑ Christ and Kern (1955), p. 243.

- ^ The philological as well as the historical significance of the activity that the subscriptions record is similarly disputed. Generalization is clearly impossible. Some texts were corrected by students as part of their training. Others appear to amount to nothing more than the correcting of one's own copy for personal use. Persius was revised twice by a young officer, Flavius Julius Tryphonianus Sabinus, while he was on military service in Barcelona and Toulouse; he worked "sine antigrapho" ["without a critical sign"], as he disarmingly tells us, and "prout potui sine magistro" ["if possible without a teacher"]. Such protestations inspire little confidence in the quality of the product, but may nevertheless suggest that correction against an exemplar and the help of a professional was what one might reasonably expect. (...) Whether the practice did anything to promote significantly the survival of classical literature is doubtful, and the value of these subscriptions for us may lie more in their historical interest. Reynolds and Wilson (1991), p. 42.

- ↑ A more probable hypothesis is that the process had been given special point and impetus by the transference of literature from roll to codex, as works were brought together and put into a new and more permanent form. But subscriptions continued even when that process was complete and must, whatever the original motivation, have become a traditional practice. Reynolds and Wilson (1991), p. 42.