Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( Greek Πυθαγόρας Pythagóras ; * around 570 BC in Samos ; † after 510 BC in Metapont in Basilicata ) was an ancient Greek philosopher ( pre-Socratics ) and founder of an influential religious-philosophical movement. At the age of forty he left his Greek homeland and emigrated to southern Italy. There he founded a school and was also politically active. Despite intensive research efforts, he is still one of the most enigmatic personalities of antiquity. Some historians count him among the pioneers of the early Greek philosophy , mathematics and natural science, others believe that he was primarily or exclusively a herald of religious teachings. Maybe he could connect these areas. The Pythagoreans named after him remained significant in terms of cultural history even after his death.

Life

Because of the lack of reliable sources, the proliferation of legends and contradictions between the traditional reports, many statements about the life of Pythagoras in the scientific literature are controversial. The current state of research gives the following picture: Pythagoras was probably around 570 BC. Born as the son of Mnesarchos, who lived on the island of Samos . Mnesarchos probably did not come from an elegant Sami family (as was claimed), but was a successful immigrant merchant (according to other tradition, a stone cutter ). The philosopher Pherecydes of Syros is most frequently mentioned as the teacher of Pythagoras . In his youth, Pythagoras is said to have stayed in Egypt and Babylonia for study purposes ; According to various reports, he made himself familiar with local religious beliefs and scientific knowledge and then returned to Samos. There had around 538 BC BC Polycrates seized power with his brothers and later established his sole rule. Pythagoras opposed this tyrant and left the island. According to the dating of the chronicler Apollodorus , he traveled in 532/531 BC. From.

No earlier than 532 BC. BC, at the latest 529 BC Pythagoras appeared in the Greek-populated southern Italy and founded a school in Croton (today Crotone in Calabria ). Its members (i.e. the inner circle) formed a close community, committed themselves to a disciplined, modest way of life (“Pythagorean way of life”) and pledged to be faithful to one another. Pythagoras, who was an excellent speaker, gained great influence on the citizenship, which he also asserted politically. He also gained supporters in other parts of the region, even among the non-Greek population. In Kroton's conflict with the city of Sybaris , which was apparently provoked by the Sybarites, he advocated a firm stand. Because, at the instigation of Pythagoras, Croton refused to hand over refugee sybaritic oppositionists, 510 BC broke out. The war ended with the destruction of Sybaris.

After the victory there were internal tensions in Croton, among other things because of the distribution of the conquered land; the displeasure of the citizens was directed against the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras then moved to Metapontion (today Metaponto in Basilicata ), where he spent the rest of his life. It was only after his departure from Croton that the conflict broke out openly there, and the Pythagoreans were defeated. Statements that many of them were killed at the time may be based on confusion with later riots. A different tradition, according to which Pythagoras stayed in Croton and fell victim to the unrest there, is not credible. There is no evidence to date his death. The Metapontians, with whom Pythagoras was in high regard, converted his house into a Demeter sanctuary after his death .

Pythagoras was married. According to some sources, his wife was called Theano (according to another tradition a daughter of the philosopher) . He had children including, if tradition can be trusted, a daughter named Myia . Some sources name alleged names of other children of Pythagoras, but the credibility of this information is very skeptical in research.

Teaching

Since no writings by Pythagoras have come down to us, a reconstruction of his teaching encounters great difficulties. The ancient tradition known to us consists largely of late sources that did not arise until the Roman Empire - more than half a millennium after Pythagoras' death. The ancient references and reports are full of contradictions and heavily legendary. The goal of many authors was to glorify Pythagoras, some wanted to vilify him. Therefore, despite intensive efforts to clarify this since the 19th century - the special literature comprises hundreds of publications - the opinions of researchers still differ widely, including on fundamental issues. A major difficulty lies in distinguishing between the views of later Pythagoreans and the original teaching.

In the 5th century BC The poet Ion of Chios claimed that Pythagoras wrote poetry, and authors of the Roman Empire named titles of works that he allegedly wrote. Among the poems that have been ascribed to him were in particular a “Holy Speech” ( hieròs lógos ), the first verse of which has survived, and the “ Golden Verses ”, a poem popular in antiquity and commented on several times (71 hexameters , Latin title Carmen aureum ). It contains rules of life and religious promises and offers a comprehensive introduction to Pythagorean thought. This poem as a whole was certainly not written by Pythagoras, but it may contain individual verses from the "Holy Speech" from him.

Research Opinions

In research there are two opposing directions that represent very different Pythagorean concepts. One direction (Erich Frank, Karl Ludwig Reinhardt , Isidore Lévy, Walter Burkert , Eric Robertson Dodds ) sees Pythagoras as a religious leader with little or no interest in science; According to Burkert, he belongs to the shaman type ("shamanism thesis"). The opponents of the shamanism thesis include Werner Jaeger , Antonio Maddalena, Charles H. Kahn and above all Leonid Zhmud , who worked out the opposite interpretation of Pythagoras in detail. It says that Pythagoras was primarily a philosopher, mathematician and scientist ("science thesis"). Some historians of philosophy seek an intermediate position between the two directions, and not all who reject one thesis are advocates of the other.

The shamanism thesis was substantiated in detail by Walter Burkert. It can be summarized as follows: Pythagoras very likely did not make a single contribution to arithmetic, geometry, music theory and astronomy, nor did it intend to do so. His concern was not a scientific one, but rather speculative cosmology , number symbolism and especially the application of magical techniques in the sense of shamanism. To his followers he was a superhuman being and had access to infallible divine knowledge. The miracles attributed to him served to legitimize this claim. The Pythagoreans formed a cult community which imposed a rigorous requirement of silence on their members with regard to their rites , and were bound by numerous rules that had to be strictly followed in everyday life. The purpose of the school was primarily religious and included political activities. Scientific endeavors were added - if at all - only after the death of Pythagoras. One cannot speak of a Pythagorean philosophy during the lifetime of Pythagoras, but only from the time of the Pythagorean Philolaos . Overall, Pythagoras' understanding of the world was pre-scientific and mythical. Burkert illustrates this with parallels to ancient Chinese cosmology ( Yin and Yang ) and to archaic ideas of indigenous peoples .

Opposite this view is the scientific thesis, which is represented in particular by Leonid Zhmud. It says that the phenomena typical of shamanism did not exist in the Greek-speaking cultural area at the time of Pythagoras. This line of research rejects the thesis of a worldwide widespread "Pan-shamanism", which determines shamanism on the basis of certain phenomenological characteristics and considers the assumption of historical connections between the peoples concerned to be unnecessary. Zhmud argues that there was no shamanism among the Scythians and that Siberian shamanism could not influence Greece or southern Italy without Scythian mediation. In his opinion, the accounts of the Pythagorean students' belief in the superhuman abilities and deeds of their teacher and the descriptions of the school as a religious bond with a secret doctrine and strange taboos are implausible. This picture came partly from ridiculous comedy poets, partly it was an expression of corresponding inclinations in the Roman Empire. The historical Pythagoras was a philosopher who was concerned with mathematics, music theory and astronomy and whose students carried out relevant research. Among other things, some of Euclid's theorems are likely to go back to Pythagoras. There was no specifically Pythagorean cult and rite, the school was not a cult community, but a loose association ( hetairie ) of researchers. These were not sworn to the dogmas of the school founder, but represented different opinions.

Both directions make weighty arguments. For the shamanism thesis, the legends are cited about miracles and spectacular skills of the master, including fortune telling, bilocation and the ability to talk to animals. The legend that he had a golden thigh was used to identify him with Apollo ; some considered him the son of Apollo. On the other hand, the contemporary Heraclitus wrote that Pythagoras did more studies ( historíē ) than any other person. This statement is made in favor of the scientific thesis, precisely because it comes from a contemporary opponent who by no means wants to praise Pythagoras, but rather accuses him of “ignorance”. Heraclitus accuses Pythagoras of plagiarism , by which he apparently means exploitation of natural-philosophical and natural-historical prose.

According to a tradition that is controversial today and generally accepted in antiquity, Pythagoras was the inventor of the terms "philosophy" and "philosopher". Herakleides Pontikos reports that Pythagoras attached importance to the distinction between the "wise man" ( sophós ) and a "wisdom friend " ( philósophos ) striving for wisdom , whereby he counted himself among the philosophers, since only God is really wise. Such modesty is incompatible with Burkert's shamanism thesis, according to which Pythagoras was worshiped by his followers as an infallible superhuman being. Burkert denies the credibility of Herakleides Pontikos' report, while proponents of the scientific thesis also take the opposite position in this regard.

The use of the term “cosmos” to denote the harmoniously ordered whole of the world was also introduced by Pythagoras, according to ancient information. Burkert and other researchers doubt the reliability of this tradition; Zhmud considers it credible.

mathematics

Already in the 4th century BC In BC Aristotle and Aristoxenus traced the beginnings of mathematics among the Greeks back to the Pythagoreans and Pythagoras. In late antiquity and the Middle Ages , the belief was widespread that Pythagoras was the founder of mathematics. This also meant geometry, the most important part of mathematics for the ancient Greeks. The tradition of Pythagoras' stay in Egypt fitted in with this, because Herodotus was already convinced that the geometry originally came from Egypt, that it was a result of the need to constantly re-survey the land after the regular floods of the Nile. Isocrates already assumed that Pythagoras owed his mathematics and astronomy to the Egyptians. Furthermore, Pythagoras was also considered a mediator of mathematical knowledge of the Babylonians, because it was assumed that he had stayed in Babylon in his youth.

Following this tradition, the view is widespread to the present day that mathematics received essential impulses from Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans. A considerable number of science historians also agree. Since the early 20th century, however, research has also paid tribute to Greek mathematics, which developed independently of the Pythagorean tradition.

The details are controversial, including the role of Pythagoras as a mediator of Egyptian and Oriental knowledge. Zhmud considers the reports of study trips to Egypt and Babylon to be unhistorical. He also points out that Greeks did not learn any foreign languages at that time and that it would have been extremely difficult for Pythagoras to acquire knowledge of the Akkadian and Egyptian languages as well as the hieroglyphs and cuneiform and then also to understand specialist literature. Therefore, Zhmud regards the mathematical knowledge of Pythagoras as its independent achievements. The speculative theory of numbers or “number mysticism” with the principle “Everything is number”, which is often equated with Pythagoreanism, did not yet exist in the early Pythagorean period, according to Zhmud, but it was Platonism that gave the impetus to its emergence.

Burkert takes the opposite point of view with his shamanism thesis. His reasoning is as follows: There is no evidence that Pythagoras made a single contribution to arithmetic or geometry. His interest was not in mathematics as a science dealing with quantities, calculating and proving, but looking at numbers from a qualitative point of view. It was about different numbers in the sense of a number symbolism certain non-mathematical properties such as "male" and "border forming" (for the odd numbers), "female" and "unlimited" (for the even numbers), "fair" or "virgin" “To assign and thus gain a principle of order for his cosmology. Burkert compares this approach, which is not about quantity, but about the order of the cosmos and the qualitative correspondence between its components, with the Chinese conception of yin and yang . Just like in Pythagorean numerology, in Chinese the original opposition of even and odd numbers is fundamental and the odd numbers are viewed as male. The statement "Everything is number", understood in this speculative, cosmological sense, was a core component of Pythagoras' worldview according to the interpretation of the shamanism thesis.

The contrast between the two research directions can also be seen in individual controversial points:

- Pythagoras is traditionally considered to be the discoverer of the Euclidean geometry theorem, known as the Pythagorean theorem, about the right triangle. This phrase was known to the Babylonians centuries before Pythagoras. It is not known whether they knew any proof for the theorem. Zhmud thinks that Pythagoras has found proof, while Burkert argues in line with the shamanism thesis that there is no evidence for this and that Pythagoras was not interested in mathematical evidence at all.

- A pupil of Pythagoras, Hippasus of Metapont , is said to have been the first to find the construction of the dodecahedron inscribed in a sphere and to have also recognized that certain geometric quantities (such as the ratio of the diagonal and the side of a square) cannot be expressed by integer number ratios ( incommensurability ). A late tradition claims that Hippasus published these discoveries and thus betrayed secrets from the perspective of the Pythagoreans. Thereupon he was expelled from the community and perished in a shipwreck, which was to be interpreted as divine punishment. Older research interpreted this as a “fundamental crisis” of Pythagoreanism: Hippasus had destroyed the basis of Pythagorean mathematics, which said that all phenomena can be explained as manifestations of whole-number ratios. The Pythagoreans had been plunged into a serious crisis by his discovery of mathematical irrationality ; for this reason they would have excluded Hippasus and interpreted his death as divine punishment. This view is rejected by both Burkert and Zhmud, but for different reasons. Burkert believes that the overcoming of irrationality took place step by step and did not cause the Pythagorean theory of numbers to shake, since it did not start from the axiom that all quantities are commensurable . Zhmud sees Hippasus as the real discoverer of irrationality, but believes that the rift between Hippasus and Pythagoras had nothing to do with it and that there can be no talk of betrayal of secrets, but that the contrast between the two was purely political.

- Among the achievements that have been ascribed to Pythagoras is the foundation of the theory of proportions; he is said to have introduced the term lógos in the mathematical sense of "proportion". This older research opinion continues to be held by proponents of the science thesis. The ancient sources describe the theory of the three means ( arithmetic , geometrical and harmonic mean ) as a specifically Pythagorean innovation . The means may already have appeared in Babylonian arithmetic rules, but the Babylonians did not know the concept of proportion. The reasoning and terminology can thus be an achievement of Pythagoras or Pythagoreans. Burkert objects that it has not been proven that Pythagoras founded a theory of proportions. He argues that the calculation of proportions was already known to Anaximander , who understood the world as geometrical by its nature and explained it with mathematical proportions. The Pythagoreans apparently played a role in the development of the Middle Doctrine, but it is unclear when and by whom this happened.

A main element of the early Pythagorean numerical theory was the Tetraktys ("tetrad"), the group of the numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4, the sum of which is 10, which was used by Greeks and "barbarians" (non-Greeks) as the basic number of the decimal system . In Pythagoreanism, the four was regarded as a fundamental number for the world order, alongside the “perfect” ten. Possibly they played with it: the one ( ancient Greek τὸ ἕν to hen , Latin unum ), dyad (ancient Greek dýas " twoness "), trias (from ancient Greek tri "three": "trinity") and the tetraktys ( Greek τετρακτύς (τετραχῇ) tetraktýs " quartet " or "group of four").

music

The view that Pythagoras was the founder of the mathematical analysis of music was widespread and accepted in ancient times. Even Plato led the musical theory of numbers back to the Pythagoreans, his pupil Xenocrates wrote the crucial discovery Pythagoras himself. It was about the representation of the harmonic intervals by simple numerical ratios. This was illustrated by measuring the length of vibrating strings. Apparently some Pythagoreans proceeded empirically, because Plato, who demanded a purely speculative music theory and distrusted empiricism, criticized them in this regard.

In the Roman Empire, the legend of Pythagoras was told in the forge . She reports that Pythagoras passed a smithy and noticed harmony in the tones of the blacksmith's hammers. He found that the consonance depended on the weight of the hammers. He then experimented at home with strings of the same length, which he loaded with weights, and came to the result that the sound height corresponds to the weight of the metal body and that the pure intervals of octaves , fourths and fifths come about through measurable proportions. This is said to be the first to make musical harmony mathematically representable. Such experiments cannot have taken place in the traditional manner, however, since the oscillation frequency is neither proportional to the weight of a hammer nor to the tension of a string. Thus this legend is an invention, or at least based on an imprecise tradition.

According to the shamanism thesis, as in geometry, it was not the concern of Pythagoras in music to grasp conditions through measurement. Rather, it was more a matter of finding symbolic relationships between numbers and tones and thus classifying music as well as mathematics in the structure of his cosmology. The scientific thesis takes the opposite point of view here too. According to her, Pythagoras was the discoverer of musical harmony; he proceeded empirically and made use of the monochord . His students continued the research. Burkert, however, doubts that there was already a monochord with an adjustable bridge at that time.

The tradition according to which Pythagoras used music specifically to influence undesirable affects, i.e. operated a kind of music therapy, is classified as early Pythagorean by research.

astronomy

It is undisputed that Greek astronomy (especially the exact knowledge of the planets) is based on Babylonian. The Greek planet names go back to the Babylonian. A fundamental difference, however, is that the Babylonians were not interested in the explanation, but only in the calculation and prediction of the events in the sky, whereas the Greeks turned their attention to the astronomical theory.

Older research saw Pythagoras in a mediating role for astronomy - as well as for mathematics - because of his journey to Babylon. In this area too, the two opposing images of Pythagoras lead to opposite results:

According to the shamanism thesis, the Greeks did not adopt the Babylonian planetary order until around 430, long after Pythagoras' death. Only then did the oldest Pythagorean model, that of the Pythagorean Philolaos, emerge . It makes the earth revolve around a central fire, with the inhabited areas on the side always facing away from this fire; on the other side of the central fire is a counter-earth that is also invisible to us. The moon, sun and five planets also revolve around the central fire. In Burkert's view, this system was not a result of astronomical observations, but a cosmological myth. Burkert thinks that Pythagoras did not practice any empirical astronomy. He points out that, according to Aristotle, some Pythagoreans counted a comet among the planets, which is incompatible with the system of Philolaus; this was therefore not an original model of Pythagoras, which as such would have been binding for the whole school. The Pythagoreans also had no unanimous opinion about the Milky Way.

Zhmud comes to the opposite conclusion. He considers the report on Pythagoras' trip to the Orient to be a legend without a historical core. In his view, the Babylonian influence on Greek astronomy was minimal. In his view, there was an original astronomical model of the Pythagoreans before Philolaos, on which Platonic astronomy was also based. It provided for a spherical earth in the center of the cosmos, around which the sphere of fixed stars rotated from east to west as well as the moon, sun and the five planets known at the time from west to east. Older proponents of the scientific thesis were of this opinion.

The idea of the harmony of the spheres or - as the name is in the oldest sources - "heavenly harmony" is certainly of Pythagorean origin . According to ancient traditions - which differ from one another in detail - these are tones that are produced by the planets in their strictly uniform circular movements and together result in a cosmic sound. However, this is inaudible to us, since it sounds continuously and we would only become conscious through its opposite, through a contrast between sound and silence. According to a legend, Pythagoras was the only person who could hear the heavenly harmony.

Burkert thinks that this idea was not originally related to astronomy, but only to the ability for extra-sensory perception, which was ascribed to Pythagoras as a shaman. There was no elaborate system during Pythagoras' lifetime. Zhmud, on the other hand, believes that it was originally a physical theory in which astronomical and acoustic observations and considerations were combined. He also points out that the tones of the heavenly bodies could only be thought of as sounding simultaneously, not as successive. Therefore one can speak of a sound, but the popular term “music of the spheres” is certainly inappropriate for this.

politics and society

Pythagoras had followers in a number of Greek cities in southern Italy. What is certain is that the Pythagoreans did not isolate themselves from social life, but strove for influence in politics, and that Pythagoras himself was politically active and therefore had bitter opponents. The reports are contradicting in some details. Diogenes Laertios writes that Pythagoras exercised political power with the community of his disciples in the city of Croton, where he lived for a long time. He is said to have given the city an aristocratic constitution and ruled according to this. This statement is classified by research as implausible, but it can be assumed that Pythagoras and his supporters in the city council and in the popular assembly asserted his point of view and was partially successful. Excerpts from four speeches in which he is said to have explained his ideal of virtue in Kroton have survived - one to the city council, one to the young men, one to the boys and one to the women. It is unclear whether the surviving texts contain authentic material, but the content seems to be early Pythagorean. The decision of the crotonians not to hand over refugees from Sybaris to this city, but rather to accept a war, which then ended with the conquest and destruction of Sybaris, was due to the intervention of Pythagoras. His influence also aroused violent opposition, which prompted him to leave Croton and move to Metapont.

Only decades after the death of Pythagoras, around the middle of the 5th century, there were bloody conflicts over the Pythagoreans in several cities, which ended catastrophically for them; they were partly killed and partly driven away.

The background to the hostility against the community and its founder is difficult to understand; According to some reports, personal motives of the opponents, such as envy and resentment, played a major role. As far as fundamental questions came into consideration, the Pythagoreans were on the side of the "aristocracy" and their opponents on that of the "democracy". The refugees from Sybaris, for whom Pythagoras stood up, were wealthy citizens who had been expropriated and exiled at the instigation of a popular leader. In any case, in accordance with their general ideal of harmony, the policy of the Pythagoreans was conservative and focused on stability; this made them allies of the sexes traditionally dominant in the Council. Their natural opponents were the popular orators, who could only come to power by influencing the masses and who used dissatisfaction to agitate for an overthrow.

Religion and theory of the soul

The Pythagoreans considered the harmony they assumed in nature and especially in the even circular movements of the heavenly bodies as a manifestation of a divine world control. In the epoch of Hellenism they had an astrological fatalism , that is, the doctrine of the inevitable eternal return of all earthly conditions according to the cyclical nature of the celestial movements. According to this myth, when all planets have returned to their original position after a long cosmic period, the “Great Year”, world history begins again as an exact repetition. This idea, which was later also widespread among Stoics and was taken up by Nietzsche in modern times, was traced back to Pythagoras in antiquity - whether rightly or not is uncertain.

What is certain, however, is that Pythagoras was convinced of the transmigration of souls and did not assume any essential difference between human and animal souls. The Orphics had already represented this religious idea before . It presupposed the conviction of the immortality of the soul. Legend has it that Pythagoras was able to remember his previous incarnations, which included the Trojan hero Euphorbos . Pythagoras is said to have recognized the shield of Euphorbos, which was kept as booty in Argos in the temple of Hera, as his own.

The core of the original Pythagoreanism also included vegetarianism , which was referred to as "abstaining from the ensouled". This vegetarianism was religiously and ethically motivated; In accordance with the principle of abstention, animal sacrifices were also discarded in addition to the meat food. Pythagoras himself was a vegetarian; to what extent his followers followed him in this is unclear. Apparently there was no binding requirement for everyone, but at least the smaller group of students probably lived a vegetarian life.

Famous in ancient times was a strict taboo of the Pythagoreans against the consumption of beans. Research unanimously suggests that the bean ban was due to Pythagoras himself. Whether the motive for this was exclusively mythical-religious or dietary and which line of thought was behind it was already debatable in ancient times and has not yet been clarified. The hypothesis considered in modern times of a connection with favism , a hereditary enzyme disease in which the consumption of field beans ( Vicia faba ) is dangerous to health, has no concrete support in the sources and is therefore speculative.

Student community

Also with regard to the organization and the purpose of the community founded by Pythagoras, the views in research differ widely. The shamanism thesis corresponds to the idea of a religious union, the members of which are bound to strict secrecy and who were completely convinced of the divinity of their master and had to ceaselessly obey a multitude of archaic taboos. The opposite view (scientific thesis) says that it was originally a loose association of autonomously researching individuals, comparable to the later schools of Plato and Aristotle . There are indications for both interpretations. The scientific thesis is supported by the fact that the Pythagoreans apparently had very different views on religious-philosophical and natural history issues. The fact that the Pythagoreans placed great value on friendship and mutual unconditional loyalty speaks in favor of the assumption of a relatively close union committed to binding principles. In contrast to the schools of Plato and Aristotle, the Pythagoreans apparently did not have a generally recognized scholar (head of the school) after the death of Pythagoras .

By the middle of the 5th century at the latest, there were two groups among those who professed the Pythagorean tradition, the "acousmatists" and the "mathematicians"; in later sources there is also talk of "exoterics" and "esoterics", in the 4th century BC. A distinction was made between "Pythagoreans" and "Pythagorists". The acousmatic orientated themselves on " Akusmata " (heard), the "mathematicians" on "Mathemata" (learning objects, empirical knowledge; not only especially mathematics in the modern sense of the word). According to a report that some researchers trace back to Aristotle, a split occurred between them at an unknown point in time after the school founder died, with each group claiming to continue the original tradition of Pythagoras. It is unclear whether or to what extent the two directions already existed during Pythagoras' lifetime and were wanted by him and, if so, which one dominated at that time. The mathematicians pursued studies in the sense of the scientific thesis, while the acousmatists orientated themselves on religious-philosophical teachings, for which they referred to the oral instructions of Pythagoras. The acousmatists evidently had a religious belief in authority, the conviction of the superhuman nature and infallibility of the master in the sense of the shamanism thesis. Therefore, they simply responded to objections with "proof of authority" ("He [Pythagoras] said it"). That was criticized by mathematicians. According to later sources, according to which there was an esoteric secret doctrine of Pythagoras, which was only revealed to the acousmatists who were bound to strict silence, Zhmud considers untrustworthy, while Burkert takes the opposite position here too and brings the original Pythagoreanism close to the mystery cults .

The Pythagorean concept of friendship, which lives on in anecdotes, played an important role. Pythagoras is said to have preached and realized an ideal of universal friendship and harmony, which is reminiscent of the myth of the paradisiacal golden age . How friendship was embedded in the general theory of harmony is shown by a representation from late antiquity, but probably from an early Pythagorean source:

“Pythagoras taught the friendship of everyone with everyone with marvelous clarity: friendship of the gods with man through piety and knowing veneration, friendship of teachings with one another and in general friendship of the soul with the body, friendship of the rational with the species of the unreasonable through philosophy and you own mental outlook. Friendship between people, friendship among fellow citizens through observance of the law, which keeps the state healthy, friendship between people of different origins through a correct knowledge of nature, friendship between man and woman, children, siblings and housemates ... friendship of the mortal body in itself, pacification and reconciliation of opposing forces that are hidden in him ... That the name 'friendship' is one and the same in all these things and that it summarizes them dominantly, ... Pythagoras discovered and established. "

According to ancient sources, the principle prevailed among the students of Pythagoras that the property of the friends was common ( koiná ta tōn phílōn ), ie a "communist" community of property. However, if it was actually practiced, this concept seems to have only been implemented by a small group of people. There are also reports of Pythagoreans who had private property and generously supported each other in material emergencies. This, too, was a consequence of the idea of the common good of friends. Private property was not discarded, but Pythagoras sharply opposed luxury and advocated a simple, frugal way of life - like many later ancient philosophers.

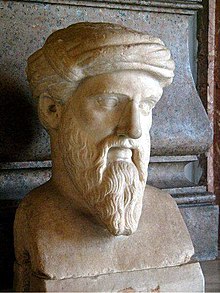

iconography

Several (at least two) statues of Pythagoras are attested in ancient literature. One was in Rome, another, which showed him standing, in Constantinople .

The reverse of bronze coins minted on Samos in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD depicts Pythagoras standing or seated. The seated Pythagoras holds a scepter in his left hand ; the symbol of rulership identifies him as a spiritual prince. In his right hand, like the standing Pythagoras, he is holding a staff with which he points to a globe. These coin images are designed based on book illustrations, statues or reliefs. For a 400 n. Chr. Embossed contorniates showing the philosopher with a long goatee and head tie, sitting in a thoughtful pose on an armchair, was probably a book illustration of the pattern. Two silver coins from Abdera (around 430–420 BC) show the head of a man with a short beard in a line square with the inscription Pythagores ; obviously the philosopher is meant.

A bronze bust in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples , which was found in the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum , as well as a marble herme in the Capitoline Museums in Rome very likely represent Pythagoras. The turban-like headgear of the philosopher speaks for this , a component of oriental costume, which apparently just as the head bandage on the Kontorniat is said to remind of the legend of Pythagoras' trip to India. From the bronze bust dating from around 360-350 BC. Seven replicas have been preserved. The herm is dated around AD 120.

In the second half of the 4th century BC Two reliefs were created. One of them comes from Sparta and is in the local museum. It shows the seated Pythagoras together with Orpheus in a landscape with animals. His attribute is an eagle. He holds a closed scroll in his left hand and an open scroll in his right. Apparently the connection between the Orphic and the Pythagorean doctrine should be shown. The other relief, found on Samos, shows Pythagoras seated with muses. One of the muses wreaths him. A pointing stick and a box for scrolls identify him as a philosopher.

reception

In antiquity as well as in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, Pythagoras was one of the best-known ancient personalities, although the Pythagoras image was strongly influenced by legends.

Antiquity

Aftermath of teaching

When the school of Pythagoras after the middle of the 5th century BC In the course of political turmoil, the continuity was broken, although individual scattered Pythagoreans continued to strive to continue the tradition and make it at home in Greece. The city of Taranto was an exception , where Pythagoreanism still flourished in the 4th century.

Plato mentions Pythagoras or the Pythagoreans only twice by name. However, he had already come into contact with Pythagoreans on his first trip to Italy and in particular remained in contact with the Pythagorean Archytas of Taranto . Of his dialogues , two of the most famous, the Timaeus and the Phaedo , are influenced by Pythagorean thought. The researchers' assumptions about how strong this influence was and how it actually manifested itself are largely speculative, however. Plato's pupil and successor as scholarch (head) of the academy , Speusippus , wrote a book on Pythagorean numbers, and Speusippus' successor Xenocrates also devoted his own book to the subject of Pythagoreanism. Aristotle was also very interested and critical of Pythagoreanism, but most of what he wrote about it belongs to the lost part of his works.

In the 1st century BC There was a revival in the Roman Empire. This "New Pythagoreanism", which lasted into late antiquity, was largely borne by Platonists and Neoplatonists, who hardly distinguished between Pythagoreanism and Platonism. In New Pythagoreanism, early Pythagorean ideas were fused with older and younger legends and (new) Platonic teachings.

Judgments on Pythagoras

In his lifetime Pythagoras was controversial; his political activities created opponents for him, and his contemporary Heraclitus sharply criticized him. Heraclitus referred to him as a “ swindler ” ( kopídōn archēgós ) and accused him of “omniscience”, which Pythagoras practiced without understanding, that is, mere accumulation of knowledge without real understanding. Heraclitus lived in Ephesus in Asia Minor, so there was already news there about the work of Pythagoras in Italy. Another contemporary, the Italian philosopher Xenophanes , was also one of the opponents. In some sources echoes of the political conflicts can be found; there is talk of Pythagoras and his disciples striving for tyranny .

The judgment of the ancient posterity, however, was almost unanimously very favorable. Only occasionally were individual religious views of Pythagoras mentioned ironically. Empedocles gave great praise, Herodotus and Plato expressed themselves respectfully. The influential historian Timaeus of Tauromenion evidently had a sympathy for Pythagoras.

Around 430-420 coins with the portrait and name of Pythagoras were minted in the city of Abdera in Thrace. This was a unique honor for a philosopher at the time, especially since Abdera was not his hometown. This is probably related to the fact that the philosopher Democritus came from Abdera and lived there at the time. Democritus was heavily influenced by Pythagoreanism.

The Romans followed a council from the Oracle of Delphi in the late 4th century that said they should make an image of the bravest and one of the wisest Greeks. They erected a statue of the general Alcibiades and one of Pythagoras on the Comitium . Reporting this, Pliny the Elder expresses amazement that they chose Pythagoras and not Socrates . In Rome at the latest in the early 2nd century BC A rumor (though incompatible with the chronology) according to which the second Roman king, the legislator Numa Pompilius , who was revered for his wisdom , was a Pythagorean; this notion testifies to the high standing of Pythagoras. Cicero pointed to the tremendous, long-lasting authority of Pythagoras in southern Italy.

The sources of the Roman Empire portray Pythagoras as a reformer who powerfully countered the moral corruption of his time and renewed virtues through his example and eloquence. In the 15th book of his Metamorphoses Ovid paints a very favorable picture of the philosopher's wisdom and goodness. The Pythagorean Apollonius von Tyana or an unknown author of the same name and the Neo-Platonists Porphyrios and Iamblichos wrote biographies of Pythagoras. Porphyrios and Iamblichos described Pythagoras as the archetype of a noble wisdom teacher and benefactor. Christians in the 2nd century ( Clement of Alexandria , Hippolytus of Rome ) also expressed respect .

middle Ages

In the Latin-speaking world of scholars of the Middle Ages, the tremendous reputation that Pythagoras enjoyed in antiquity had a strong effect, although at that time none of the ancient biographies of the philosopher were available and only a few pieces of information were available. His conception of the fate of the soul after death, which was incompatible with church teachings, was violently condemned, but this hardly damaged the reputation of his wisdom. In addition to Ovid's depiction and that of Junianus Justinus , the main sources at that time were the late antique and patristic authors Martianus Capella , Hieronymus , Augustine , Boethius , Cassiodorus and Isidore of Seville . The medieval educated saw in Pythagoras the founder of musicology and mathematics, a prominent herald of the immortality of the soul and the inventor of the term "philosophy".

The symbolism of the “Pythagorean letter” Y, which with its forked shape served as a symbol for the crossroads of human life: at the crossroads one had to choose between the path of virtue and that of vice. The sayings and rules of life of the Pythagoreans, sometimes formulated in mysterious veils, and the ascetic aspects of the Pythagorean moral doctrine were in harmony with medieval ideas and needs. Two works that were very popular at the time, the Speculum historiale by Vinzenz von Beauvais and the Liber de vita et moribus philosophorum (book about the life and customs of the philosophers) , which was previously wrongly attributed to Walter Burley , give an impression of the positive Pythagoras image of the late Middle Ages . Francesco Petrarca expressed his admiration for Pythagoras in the style of the Pythagorean praise common in the Middle Ages.

Two ancient commentaries on the "Golden Verses" were widespread in the Middle Ages in Arabic translation in the Islamic world.

Modern times

In the early modern period , the source base was greatly expanded. In 1433, Ambrogio Traversari had translated the philosopher biographies of Diogenes Laertios , which included a biography of Pythagoras, into Latin; the first edition of the Latin version, published in 1472, made the work known to a wider audience. Later the biographies glorifying Pythagoras were added; the one written by Iamblichus was first printed in 1598, the one by Porphyrios in 1610. A number of (new) Pythagorean letters and writings from antiquity that were wrongly ascribed to Pythagoras or people from his environment ( Pseudepigrapha ) were widespread . The letters had been in print since 1499. The “Golden Verses” were particularly valued and also used as school reading material during the Renaissance.

Overall, the Pythagorean image of the ancient New Pythagoreans and Neoplatonists dominated. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) called himself a Pythagorean. The humanist Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522) set himself the task of opening up the world of thought of Pythagoras to his contemporaries, whose teachings, according to Reuchlin, coincided with those of the Kabbalah . Giordano Bruno said that the Pythagorean method was “better and purer” than that of Plato. The astronomer and natural philosopher Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was strongly influenced by a Pythagorean perspective . He tried to show the planetary movements as an expression of perfect world harmony and to combine astronomical proportions with musical ones, which he consciously took up a core concern of the ancient Pythagoreans.

In the 18th and 19th centuries there was a nationalist tendency among Italian philosophers and cultural historians, which extolled the glorious "Italian wisdom" ( italica sapienza ), to which one also counted the teaching of Pythagoras, which was regarded as an achievement of Italy (main exponent in 18th century: Giambattista Vico , in the 19th century: Vincenzo Gioberti ). In 1873 an "Accademia Pitagorica" was founded in Naples, to which Pasquale Stanislao Mancini and Ruggero Bonghi belonged. Even in the early 20th century, the ancient historian and archaeologist Jérôme Carcopino held the view that Pythagoreanism was a specifically Italian worldview that at times had a decisive influence on the political fortunes of southern Italy.

In the 20th century, the musicologist Hans Kayser endeavored to conduct “basic harmonic research”, with which he tied in with Pythagorean thinking.

A late Pythagoras legend that still has an impact today is the claim that the philosopher invented the " Pythagoras cup ". The construction of this cup prevents you from filling it completely and then drinking it, because it causes it to suddenly empty beforehand. Such cups are produced in Samos as souvenirs for tourists. This has nothing to do with historical Pythagoras and his school.

In 1935 the lunar crater Pythagoras was named after him by the IAU . On July 22, 1959, the Pythagoras Peak followed in the Antarctic by the Antarctic Names Committee of Australia (ANCA) and on March 17, 1995 the asteroid (6143) Pythagoras . Also the plant genus Pythagorea Lour. from the willow family (Salicaceae) is named after Pythagoras.

See also

Editions and translations of sources

- Otto Apelt (translator): Diogenes Laertius: life and opinions of famous philosophers . 3rd edition, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-7873-1361-3 , pp. 111-134 ( Diogenes Laertios , Vitae philosophorum 8,1-50)

- Édouard des Places (Ed.): Porphyre: Vie de Pythagore, Lettre à Marcella . Paris 1982 (Greek text and French translation by Porphyrios , Vita Pythagorae )

- Michael von Albrecht (Ed.): Jamblich: Pythagoras. Legend - teaching - shaping life . Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-534-14945-9 (Greek text and German translation by Iamblichos , De vita Pythagorica )

- Rita Cuccioli Melloni: Ricerche sul Pitagorismo , 1: Biografia di Pitagora . Bologna 1969 (compilation of ancient sources on the life of Pythagoras; Greek and Latin texts with Italian translation)

- Maurizio Giangiulio: Pitagora. Le opere e le testimonianze . 2 volumes, Milano 2000, ISBN 88-04-47349-5 (source collection; Greek texts with Italian translation)

- Jaap Mansfeld : The Presocratics I . Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-15-007965-9 (pp. 122–203 Greek sources with German translation; some of the introduction does not reflect the current state of research)

literature

Manual illustrations

- Kurt von Fritz : Pythagoras. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume XXIV, Stuttgart 1963, Col. 172-209.

- Constantinos Macris, Katarzyna Prochenko, Anna Izdebska: Pythagore de Samos. In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques. Volume 7, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2018, ISBN 978-2-271-09024-9 , pp. 681–884, 1025–1174

- Hans Georg von Manz: Pythagoras of Samos. In: Werner E. Gerabek et al. (Ed.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1205.

- Leonid Zhmud: Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans. 1. Pythagoras. In: Hellmut Flashar et al. (Hrsg.): Early Greek Philosophy (= Outline of the History of Philosophy . The Philosophy of Antiquity. Volume 1). Half volume 1, Schwabe, Basel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7965-2598-8 , pp. 375–401, 429–434.

Overall representations, investigations

- Walter Burkert : Wisdom and Science. Studies on Pythagoras, Philolaus and Plato. Hans Carl, Nuremberg 1962.

- Walter Burkert: Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 1972, ISBN 0-674-53918-4 (revised version of Burkert's Wisdom and Science ).

- Peter Gorman: Pythagoras. A life. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1979, ISBN 0-7100-0006-5 .

- James A. Philip: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism. University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1966, ISBN 0-8020-5175-8 .

- Christoph Riedweg : Pythagoras. Life, teaching, aftermath. An introduction. 2nd, revised edition. Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-48714-9 .

- Bartel Leendert van der Waerden : The Pythagoreans. Religious brotherhood and school of science. Artemis, Zurich / Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7608-3650-X .

- Cornelia Johanna de Vogel : Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism. Van Gorcum, Assen 1966.

- Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-05-003090-9 .

- Leonid Zhmud: Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-928931-8 .

reception

- Almut-Barbara Renger, Roland Alexander Ißler: Pythagoras. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 797-818.

- Stephan Scharinger: The miracles of Pythagoras. A comparison of traditions (= Philippika. Classical studies. Volume 107). Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2017, ISBN 978-3-447-10787-7 .

bibliography

- Luis E. Navia: Pythagoras. An Annotated Bibliography. Garland, New York 1990, ISBN 0-8240-4380-4 .

Web links

- Literature on Pythagoras in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works on Pythagoras in the German Digital Library

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : Pythagoras of Samos. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- Carl Huffman: Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Karl Bormann: Article “Pythagoras” in the UTB online dictionary philosophy

- Burnet: Early Greek Philosophy. Pythagoras

- Gottwein, selection of texts on pre-Socratic philosophy

- Ovid on Pythagoras at Gutenberg.DE ( Memento from June 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Pythagorean philosophy and piety. Diogenes Laertios, Lives and Opinions of Famous Philosophers 8, 8–36 ( Memento from 23 August 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- English translation of the Vita Pythagorae of Porphyrios

Remarks

- ↑ On the dating Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, p. 51 f.

- ↑ James A. Philip: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Toronto 1966, pp. 185 f .; Nancy Demand: Pythagoras, Son of Mnesarchos . In: Phronesis 18, 1973, pp. 91-96.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, p. 50 f. is skeptical of this tradition; Peter Gorman: Pythagoras. A Life , London 1979, pp. 25–31, however, gives her trust.

- ^ Kurt von Fritz: Pythagoras . In: Pauly-Wissowa RE, Vol. 24, Stuttgart 1963, Col. 172-209, here: 179-186; James A. Philip: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Toronto 1966, pp. 189-191; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 44–48; Peter Gorman: Pythagoras. A Life , London 1979, pp. 43-68; rejecting Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, pp. 57–64.

- ↑ Leonid Zhmud: Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans , Oxford 2012, pp. 81–83.

- ^ On the dating of Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 176; Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, pp. 21-23; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, p. 51 f .; for information on dating from ancient times, see Cicero , De re publica 2, 28–30 and on this Karl Büchner : M. Tullius Cicero, De re publica. Commentary , Heidelberg 1984, pp. 197-199.

- ↑ Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, pp. 148-150.

- ↑ See also Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 203-206.

- ^ Eduard Zeller , Rodolfo Mondolfo : La filosofia dei Greci nel suo sviluppo storico , Vol. 1 (2), 5th edition, Firenze 1938, pp. 423-425, especially p. 425 note 2; Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 178 and note 20, p. 182 f .; Rita Cuccioli Melloni: Ricerche sul Pitagorismo , 1: Biografia di Pitagora , Bologna 1969, pp. 35-38.

- ↑ Pierre Boyancé : Le culte des Muses chez les philosophes grecs , Paris 1937, pp. 234-236; Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 178, note 20; Georges Vallet : Le "stenopos" des Muses à Métaponte . In: Mélanges de philosophie, de littérature et d'histoire ancienne offerts à Pierre Boyancé , Rome 1974, pp. 749–759.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 180; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, p. 55 f.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans , Oxford 2012, p. 103 (with references).

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 8.7.

- ^ Johan C. Thom: The Pythagorean Golden Verses , Leiden 1995 (text edition with English translation, introduction and commentary).

- ↑ Erich Frank took this point of view in his study Plato and the so-called Pythagoreans , Halle 1923 radical; in a later work ( Knowledge, Willing, Faith , Zurich 1955, pp. 81 f.) he moved away from the extreme position.

- ↑ Zhmud presented his position in detail in the monograph Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , published in 1997, and summarized his arguments in 2005, referring to literature that has appeared since then: Leonid Zhmud: Reflections on the Pythagorean Question . In: Georg Rechenauer (Ed.): Early Greek Thinking , Göttingen 2005, pp. 135–151.

- ↑ In the monograph Wisdom and Science (1962); In the revised English translation Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism (1972), Burkert, in response to criticism, changed some of his assumptions.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 51–60; Peter Gorman: Pythagoras. A Life , London 1979, p. 19 f.

- ↑ Heraklit, fragment B 129.

- ↑ For the interpretation of the Heraklit fragment see Leonid Zhmud: Wissenschaft, Philosophie und Religion im early Pythagoreismus , Berlin 1997, pp. 34–38.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Plato or Pythagoras? In: Hermes 88, 1960, pp. 159-177.

- ↑ Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, pp. 96-102; Robert Joly: Plato ou Pythagore? In: Hommages à Marie Delcourt , Bruxelles 1970, pp. 136–148; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 290–292.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 68–70; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 292–295.

- ↑ Aristoxenus, fragment 23; Aristotle, Metaphysics 985b23 ff.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 383 f.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 59, 143-145.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, p. 156; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, p. 32.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 418.

- ↑ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 381 ff.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, pp. 60–64, 142–151, 261–279; also Carl A. Huffman: Philolaus of Croton , Cambridge 1993, pp. 57-64. Hermann S. Schibli has a different opinion: On 'The One' in Philolaus, fragment 7 . In: The Classical Quarterly 46, 1996, pp. 114-130. See also Charles H. Kahn: Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans. A Brief History , Indianapolis 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 405 f., 441 ff .; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 160–163.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 431–440; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 170–175.

- ↑ Kurt von Fritz: The ἀρχαί in Greek mathematics . In: Archive for Conceptual History 1, 1955, pp. 13-103, here: 81 ff .; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, p. 162.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 395, 414–419.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 348–353.

- ↑ For the ancient tradition of this legend, see Flora R. Levin: The Harmonics of Nicomachus and the Pythagorean Tradition , University Park (PA) 1975, pp. 69–74; on the aftermath in the Middle Ages Hans Oppermann : A Pythagoras legend . In: Bonner Jahrbücher 130, 1925, pp. 284–301 and Barbara Münxelhaus: Pythagoras musicus , Bonn 1976, pp. 36–55.

- ↑ Barbara Münxelhaus: Pythagoras musicus , Bonn 1976, p. 37 f., 50-53.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, p. 192 ff .; Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 350–357; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 365–372; Barbara Münxelhaus: Pythagoras musicus , Bonn 1976, p. 28 f.

- ↑ Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, pp. 162–166; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, p. 364 f .; Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 355; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 181-183, 233.

- ↑ This is what Bartel Leendert van der Waerden said: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, p. 256 f.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 293–295.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 295–301, 315–328.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, pp. 57–64, 202–225; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 427–438.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 100-103, 110-115, 434 f.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 328–335.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, pp. 219–225.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 8.3; see. Porphyrios, Vita Pythagorae 21; Iamblichos, De vita Pythagorica 33.

- ↑ Kurt von Fritz: Pythagorean Politics in Southern Italy , New York 1940 (reprint New York 1977), pp. 94–97; Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, pp. 189-191; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, p. 84.

- ↑ Iamblichos, De vita Pythagorica 37-57; on the question of the source value, see Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, pp. 70–147; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 186–201.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 203-206.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 207–217.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 217–222.

- ^ Kurt von Fritz: Pythagorean Politics in Southern Italy , New York 1940 (reprint New York 1977), pp. 29–32, 97–99.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 252–268.

- ↑ Porphyrios, Vita Pythagorae 19.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, p. 55 f.

- ↑ Greek ἀποχὴ ἐμψύχων, Iamblichos, De vita Pythagorica 107; 168; 225; Porphyrios, Vita Pythagorae 7 (with reference to Eudoxus of Knidos ).

- ↑ Johannes Haußleiter : Der Vegetarismus in der Antike , Berlin 1935, pp. 97–157; Carmelo Fucarino: Pitagora e il vegetarianismo , Palermo 1982, pp. 21-31.

- ↑ On the state of research see Giovanni Sole: Il tabù delle fave , Soveria Mannelli 2004. Cf. Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 169–171; Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 164–166; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, p. 127 f.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 161–175.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, pp. 75–90.

- ^ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 71, 79–81, 90, 268 ff., 281 f.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 175–181.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 8:43 names one of his sons named Telauges as the successor of Pythagoras, but no traces of his alleged activity as headmaster have been preserved. Iamblichos, De vita Pythagorica 265 writes that the name of Pythagoras' successor was Aristaios.

- ↑ Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, p. 64 ff .; Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 187-202; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 93-104.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 190 f .; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 69–73; Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, pp. 100-104, is different .

- ↑ Ancient documents are compiled by Arthur S. Pease (ed.): M Tulli Ciceronis de natura deorum liber primus , Cambridge (Mass.) 1955, p. 149 f.

- ↑ Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, pp. 150–159 and 219; Bartel Leendert van der Waerden: Die Pythagoreer , Zurich / Munich 1979, pp. 177–180.

- ↑ a b Iamblichos, De vita Pythagorica 229-230.

- ^ Edwin L. Minar: Pythagorean Communism . In: Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 75, 1944, pp. 34-46; Manfred Wacht: Community of property . In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Vol. 13, Stuttgart 1986, Sp. 1–59, here: 2–4.

- ↑ Cornelia J. de Vogel: Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism , Assen 1966, p. 233 f .; Clara Talamo: Pitagora e la ΤΡΥΦΗ . In: Rivista di filologia e di istruzione classica 115, 1987, pp. 385-404.

- ^ Gisela MA Richter : The Portraits of the Greeks , Volume 1, London 1965, p. 79.

- ^ Karl Schefold : The portraits of ancient poets, speakers and thinkers , Basel 1997, pp. 106 f., 412 f., 424 f. (with pictures); Gisela MA Richter: The Portraits of the Greeks , Volume 1, London 1965, p. 79 and Supplement , London 1972, p. 5; Brigitte Freyer-Schauenburg : Pythagoras and the Muses? In: Heide Froning et al. (Ed.): Kotinos. Festschrift for Erika Simon , Mainz 1992, pp. 323–329, here: 327.

- ^ Karl Schefold: The portraits of ancient poets, speakers and thinkers , Basel 1997, pp. 152–155, 344 f .; Gisela MA Richter: The Portraits of the Greeks , Volume 1, London 1965, p. 79.

- ↑ Karl Schefold: The portraits of ancient poets, speakers and thinkers , Basel 1997, p. 124. For the Spartan relief see Volker Michael Strocka : Orpheus and Pythagoras in Sparta . In: Heide Froning et al. (Ed.): Kotinos. Festschrift for Erika Simon , Mainz 1992, pp. 276–283 and panels 60 and 61. For the Sami relief, see Brigitte Freyer-Schauenburg: Pythagoras und die Musen? In: Heide Froning et al. (Ed.): Kotinos. Festschrift for Erika Simon , Mainz 1992, pp. 323–329 and plate 71.

- ↑ Heraklit, fragments B 40, B 81, B 129. Doubts about the authenticity of B 129 are unfounded, see Leonid Zhmud: Wissenschaft, Philosophie und Religion im early Pythagoreismus , Berlin 1997, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreism , Berlin 1997, p. 29 f.

- ↑ This view was, for example, Theopompus ; Evidence from Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 184; see also Bruno Centrone: Introduzione ai pitagorici , Roma 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, pp. 115 f., 136 f.

- ↑ Fragment B 129. He does not mention Pythagoras by name; the reference is therefore not unequivocally certain, but the content is highly probable.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Wisdom and Science , Nuremberg 1962, p. 92.

- ^ Illustrations from Christiane Joost-Gaugier: Measuring Heaven. Pythagoras and His Influence on Thought and Art in Antiquity and the Middle Ages , Ithaca 2006, pp. 139, 141.

- ↑ Leonid Zhmud: Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Pliny, Naturalis historia 34:26. For the process and its date, see Michel Humm: Les origines du pythagorisme romain (I) . In: Les Études classiques 64, 1996, pp. 339–353, here: 345–350.

- ↑ Michel Humm: Les origines du pythagorisme romain (I) . In: Les Études classiques 64, 1996, pp. 339–353, here: 340–345; Peter Panitschek: Numa Pompilius as a pupil of Pythagoras . In: Grazer contributions 17, 1990, pp. 49-65.

- ↑ Cicero, Tusculanae disputationes 1.38; 4.2.

- ↑ The Vita written by Apollonios is lost. Traditionally, the author was Apollonios of Tyana; Peter Gorman: The "Apollonios" of the Neoplatonic Biographies of Pythagoras disagree . In: Mnemosyne 38, 1985, pp. 130–144 and Gregor Staab: The informant 'Apollonios' in the Neo-Platonic Pythagoras Vitus - wonder man or Hellenistic writer? In: Michael Erler , Stefan Schorn (eds.): The Greek Biography in Hellenistic Time , Berlin 2007, pp. 195–217.

- ↑ Christiane Joost-Gaugler: Measuring Heaven. Pythagoras and His Influence on Thought and Art in Antiquity and the Middle Ages , Ithaca 2006, p. 41 f.

- ↑ Compilation of the numerous documents (also on the literary exploitation of the motif) by Wolfgang Maaz: Metempsychotica mediaevalia . In: ψυχή - soul - anima. Festschrift for Karin Alt on May 7, 1998 , Stuttgart 1998, pp. 385–416.

- ↑ Junianus Justinus, Epitoma 20.4.

- ↑ Hieronymus, Epistula adversus Rufinum 39 f. and Adversus Iovinianum 1.42.

- ↑ Augustine, De civitate dei 8.2; 8.4; 18.37.

- ↑ Boethius, De institutione musica 1,1; 1.10-11; 1.33; 2.2-3.

- ↑ Cassiodorus, Institutiones 2,4,1; 2,5,1-2.

- ^ Isidore of Seville: Etymologiae 1,3,7; 3.2; 3.16.1; 8,6,2-3; 8,6,19-20.

- ^ Wolfgang Harms : Homo viator in bivio. Studies on the Imagery of the Path , Munich 1970; Hubert Silvestre: Nouveaux témoignages médiévaux de la Littera Pythagorae . In: Le Moyen Age 79, 1973, pp. 201-207; Hubert Silvestre: Pour le dossier de l'Y Pythagoricia . In: Le Moyen Age 84, 1978, pp. 201-209.

- ↑ Vincent de Beauvais, Speculum historiale 3, 23-26 (based on the Douai 1624 edition; correct would be 4.23-26).

- ↑ The Pythagoras biography there is edited by Jan Prelog: De Pictagora phylosopho . In: Medioevo 16, 1990, pp. 191-251.

- ↑ Christiane Joost-Gaugler: Measuring Heaven. Pythagoras and His Influence on Thought and Art in Antiquity and the Middle Ages , Ithaca 2006, pp. 74 f .; Paolo Casini: L'antica sapienza italica. Cronistoria di un mito , Bologna 1998, p. 35 f.

- ↑ On these writings see Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in der Spätantike , Munich 2002, pp. 69–72; Alfons Städele: The letters of Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans , Meisenheim 1980 (edition of the Greek texts with German translation and commentary).

- ^ Paolo Casini: L'antica sapienza italica. Cronistoria di un mito , Bologna 1998, pp. 57-61.

- ↑ Vincenzo Capparelli: La sapienza di Pitagora , vol. 1: Problemi e fonti d'informazione , Padova 1941, p. 1.

- ↑ Jérôme Carcopino: La basilique pythagoricienne de la Porte Majeure , Paris 1927, p. 163.

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 24919

- ↑ Lotte Burkhardt: Directory of eponymous plant names - Extended Edition. Part I and II. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin , Freie Universität Berlin , Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5 , doi: 10.3372 / epolist2018 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pythagoras |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pythagoras of Samos |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Greek mathematician and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 570 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 510 BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Metapontium , Basilicata |